Parkinson's disease

| Parkinson's disease | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Frequency | 0.2% (Canada) |

Parkinson's disease (also known as Parkinson disease, Parkinson's, idiopathic parkinsonism, primary parkinsonism, PD or paralysis agitans) is a progressive degenerative disorder of the central nervous system. It results from the death by unknown causes of the dopamine-containing cells of the substantia nigra, which is a region of the midbrain. Early in the course of the disease, the most obvious symptoms are movement-related, including shaking, rigidity, slowness of movement and difficulty with walking and gait. Later, cognitive and behavioural problems may arise, with dementia commonly occurring in the advanced stages of the disease. Other symptoms include sensory, sleep and emotional problems. PD typically becomes apparent around the age of 60 years and is unusual before the age of 40 years.

The main motor symptoms are collectively called parkinsonism, or a "parkinsonian syndrome". Parkinson's disease is often defined as a Parkinsonian syndrome that is idiopathic (has no known cause), although some atypical cases have a genetic origin. Many risk and protective factors have been investigated: the clearest evidence is for an increased risk of PD in people exposed to certain pesticides and a reduced risk in tobacco smokers. The pathology of the disease is characterized by the accumulation of a protein called alpha-synuclein into inclusions called Lewy bodies in neurons, and from insufficient formation and activity of dopamine produced in certain neurons of parts of the midbrain. Diagnosis of typical cases is mainly based on symptoms, with tests such as neuroimaging being used for confirmation.

Modern treatments are effective at managing the early motor symptoms of the disease, mainly through the use of levodopa and dopamine agonists. As the disease progresses and dopamine neurons continue to be lost, a point eventually arrives at which these drugs become ineffective at treating the symptoms, while at the same time produce a complication called dyskinesia, marked by writhing movements. Medications to treat other symptoms of PD exist. Diet and some forms of rehabilitation have shown some effectiveness at alleviating symptoms. Surgery and deep brain stimulation have been used to reduce motor symptoms as a last resort in severe cases where drugs are ineffective. Research directions include a search of new animal models of the disease and investigations of the potential usefulness of gene therapy, stem cell transplants and neuroprotective agents.

The disease is named after the English doctor James Parkinson, who published the first detailed description in An Essay on the Shaking Palsy (1817). PD is a costly disease to society. Several major organizations promote research and improvement of quality of life of those with the disease and their families. Public awareness campaigns include Parkinson's disease day on the birthday of James Parkinson, April 11, and the use of a red tulip as the symbol of the disease. People with parkinsonism who have enhanced public awareness include Michael J. Fox and Muhammad Ali.

Classification

The term parkinsonism is used for a motor syndrome whose main symptoms are tremor at rest, stiffness, slowing of movement and postural instability. Parkinsonian syndromes can be divided into four subtypes according to their origin: primary or idiopathic, secondary or acquired, hereditary parkinsonism, and parkinson plus syndromes or multiple system degeneration.[1] Parkinson's disease is the most common form of parkinsonism and is usually defined as "primary" parkinsonism, meaning parkinsonism with no external identifiable cause.[2][3] In recent years several genes that are directly related to some cases of Parkinson's disease have been discovered. As much as this can go against the definition of Parkinson's disease as idiopathic, genetic parkinsonisms with a similar clinical course to PD are generally considered true cases of Parkinson's disease. The terms "familial Parkinson's disease" and sporadic Parkinson's disease" can be used to differentiate genetic from truly idiopathic forms of the disease.[4]

PD is usually classified as a movement disorder, although it also gives rise to several non-motor types of symptoms such as cognitive difficulties or sleep problems. Parkinson plus diseases are primary parkinsonisms which present additional features.[2] They include multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration and dementia with Lewy bodies.[2]

In terms of pathophysiology, PD is considered a synucleinopathy due to an abnormal accumulation of alpha-synuclein protein in the brain in the form of Lewy bodies, as opposed to other diseases such as Alzheimer's disease where the brain accumulates tau protein in the form of neurofibrillary tangles.[5] Nevertheless, there is clinical and pathological overlap between tauopathies and synucleinopathies. The most typical symptom of Alzheimer's disease, dementia, occurs in advanced stages of PD, while it is common to find neurofibrillary tangles in brains affected by PD.[5]

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is another synucleinopathy that has similarities with PD, and especially with the subset of PD cases with dementia. However the relationship between PD and DLB is complex and still has to be clarified.[6] They may represent parts of a continuum or they may be separate diseases.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Parkinson's disease affects movement, producing motor symptoms.[1] Non-motor symptoms, which include autonomic dysfunction, neuropsychiatric problems (mood, cognition, behavior or thought alterations), and sensory and sleep difficulties, are common.[1]

Motor

Four motor symptoms are considered cardinal in PD: tremor, rigidity, slowness of movement, and postural instability.[1]

Tremor is the most apparent and well-known symptom.[1] It is the most common; though around 30% of individuals with PD do not have tremor at disease onset, most develop it as the disease progresses.[1] It is usually a rest tremor: maximal when the limb is at rest and disappearing with voluntary movement and sleep.[1] It affects to a greater extent the most distal part of the limb and at onset typically appears in only a single arm or leg, becoming bilateral later.[1] Frequency of PD tremor is between 4 and 6 hertzs (cycles per second). A feature of tremor is "pill-rolling", a term used to describe the tendency of the index finger of the hand to get into contact with the thumb and perform together a circular movement.[1][7] Such term was given due to the similarity of the movement in PD patients with the former pharmaceutical technique of manually making pills.[7]

Bradykinesia (slowness of movement) is the most characteristic clinical feature of PD and is associated with difficulties along the whole course of the movement process, from planning to initiation and finally execution of a movement.[1] The performance of sequential and simultaneous movements is hindered.[1] Bradykinesia is the most disabling symptom in the early stages of the disease.[2] Initial manifestations of bradykinesia are problems when performing daily life tasks requiring fine motor control such as writing, sewing or getting dressed.[1] Clinical evaluation is based in similar tasks consisting such as alternating movements between both hands or both feet.[2] Bradykinesia is not equal for all movements or times. It is modified by the activity or emotional state of the subject to the point of some patients barely able to walk yet being capable of riding a bicycle.[1] Generally patients have less difficulty when some sort of external cue is provided:[1][8]

Rigidity is a characterized by an increased muscle tone (an excessive and continuous contraction of muscles) which produces stiffness and resistance to limb movement.[1] When an observer moves a limb of a person with PD (the PD sufferer not contributing muscular effort consciously), the physical sign of "cogwheel rigidity" is commonly felt,[1] the limb moving by ratchety jerks as opposed to normal even movement.[1][2][9] The combination of tremor and increased tone is considered to be at the origin of cogwheel rigidity.[10] Rigidity may be associated with joint pain; such pain being a frequent initial manifestation of the disease.[1]

In the late stages postural instability is typical, which leads to impaired balance and frequent falls, and secondarily to bone fractures.[1] Instability is often absent in the initial stages, especially in younger people.[2] Up to 40% of the patients may experience falls and around 10% may have falls weekly, with number of falls being related to the severity of PD.[1]

Other motor signs and symptoms include gait and posture disturbances such as festination (rapid shuffling steps and a forward-flexed posture when walking), speech and swallowing disturbances; mask-like face expression or small handwriting but there is a big range of motor problems that can appear.[1]

Neuropsychiatric

Parkinson's disease causes neuropsychiatric disturbances which can range from mild to severe. This includes disorders of cognition, mood, behaviour, and thought.[1]

A high proportion of people with PD will have cognitive impairment in the advanced stages of the disease; however, in some cases cognitive disturbances can occur in the initial stages of the disease and sometimes prior to diagnosis.[1][11] The most common cognitive deficit in affected individuals without dementia is executive dysfunction, which can include problems with planning, cognitive flexibility, abstract thinking, rule acquisition, initiating appropriate actions and inhibiting inappropriate actions, and selecting relevant sensory information. Fluctuations in attention and slowed cognitive speed are among other cognitive difficulties. Memory is affected, specifically in recalling learned information. Nevertheless, improvement appears when recall is aided by cues. Visuospatial difficulties are also part of the disease, which are for example seen when the individual is asked to perform tests of facial recognition and perception of the orientation of drawn lines.[11]

Deficits tend to worsen with time, in many cases developing into dementia. A person with PD has a sixfold increased risk of suffering dementia,[1] and the overall rate in people with the disease is around 30%.[11] Prevalence of dementia increases in relation to disease duration, going up to 80%.[11] Dementia has been associated with a reduced quality of life in people with PD and their caregivers, increased mortality and a higher probability of attending a nursing home.[11]

Behavior and mood alterations are more common in PD without cognitive impairment than in the general population, and are usually present in PD with dementia. The most frequent mood difficulties are depression, apathy and anxiety.[1] Impulse control behaviors such as medication overuse and craving, binge eating, hypersexuality, or pathological gambling can appear in PD and have been related to the medications for the disease.[1][12] Psychotic symptoms—hallucinations or delusions—are common in late PD.[13]

Other

In addition to cognitive and motor symptoms, PD can impair other body functions. Sleep problems are a core feature of the disease and can be worsened by medications.[1] They can manifest as daytime drowsiness, disturbances in REM sleep, or insomnia.[1] Alterations in the autonomic nervous system can lead to orthostatic hypotension, oily skin and excessive sweating, urinary incontinence and altered sexual function.[1] Constipation and gastric dysmotility can be severe enough to cause discomfort and even endanger health.[14] PD is related to several eye and vision abnormalities such as decreased blink rate and dry eyes, abnormalities in ocular pursuit and saccadic movements (fast automatic movements of both eyes in the same direction) , and difficulties in directing gaze upward.[1] Changes in perception may include an impaired sense of smell, sensation of pain, and paresthesia.[1] All these symptoms occur in many cases years before diagnosis of the disease.[1]

Causes

Most people with Parkinson's disease have idiopathic Parkinson's disease (having no specific known cause). A small proportion of cases, however, can be attributed to known genetic factors. Other factors have been associated with the risk of developing PD, but no causal relationship has been proven; they will be described in the epidemiology section of the article.

PD traditionally has been considered a non-genetic disorder; however, around 15% of individuals with PD have a first-degree relative who has the disease.[2] At least 5% of people are now known to have forms of the disease that occur due to a mutation of one of several specific genes.[15]

Mutations in specific genes have been conclusively shown to cause PD. These include alpha-synuclein (SNCA), ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), parkin (PRKN), leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2 or dardarin), PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), DJ-1 and ATP13A2.[4][15] In most cases, people with these mutations will develop PD. With the exception of LRRK2, however, they account for only a small minority of cases of PD.[4] The most extensively studied PD-related genes are SNCA and LRRK2. Mutations in genes including SNCA, LRRK2 and glucocerebrosidase (GBA), have been found to be risk factors for sporadic PD. Mutations in GBA are known to cause Gaucher's disease.[15] Genome-wide association studies, which search for mutated alleles with low penetrance in sporadic cases, have yielded few positive results, but such studies have been few in number and their size small.[15]

The role of the SNCA gene is important in PD because the alpha-synuclein protein is the main component of Lewy bodies.[15] Missense mutations (mutation in which a single nucleotide is changed) of the gene, and duplications and triplications of the locus containing it, have been found in different groups with familial PD.[15] Missense mutations are rare.[15] On the other hand, multiplications of the SNCA locus account for around 2% of familial cases.[15] Multiplications have been found in asymptomatic carriers, which indicate that penetrance is incomplete or age-dependent.[15]

The LRRK2 gene (PARK8) encodes for a protein called dardarin. The name dardarin was taken from a Basque word for tremor, because this gene was first identified in families from England and the north of Spain.[4] Mutations in LRRK2 are the most common known cause of familial and sporadic PD, accounting for up to 10% of individuals with a family history of the disease and 3% of sporadic cases.[4][15] More than 40 different mutations of the gene have been found to be related to PD.[15]

Pathology

Anatomical pathology

The basal ganglia, a group of "brain structures" innervated by the dopaminergic system, are the most seriously affected brain areas in PD.[16] The main pathological characteristic of PD is cell death in the substantia nigra and, more specifically, the ventral (front) part of the pars compacta, affecting up to 70% of the cells by the time death occurs.[4]

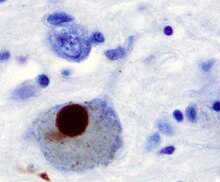

Macroscopic alterations can be noticed on cut surfaces of the brainstem, where neuronal loss can be inferred from a reduction of melanin pigmentation in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus.[17] The histopathology (microscopic anatomy) of the substantia nigra and several other brain regions shows neuronal loss and Lewy bodies in many of the remaining nerve cells. Neuronal loss is accompanied by astrocytes (star-shaped glial cells) death and activation of the microglia (another type of glial cells). Lewy bodies are a key pathological feature of PD.[17]

Pathophysiology

The primary symptoms of Parkinson's disease result from greatly reduced activity of dopamine-secreting cells due to cell death in the pars compacta region of the substantia nigra.[16]

There are five major pathways in the brain connecting other brain areas with the basal ganglia. These are known as the motor, oculo-motor, associative, limbic and orbitofrontal circuits, with names indicating the main projection area of each circuit.[16] All of them are affected in PD, and their disruption explains many of the symptoms of the disease since these circuits are involved in a wide variety of functions including movement, attention and learning.[16] Scientifically, the motor circuit has been examined the most intensively.[16]

A particular conceptual model of the motor circuit and its alteration with PD has been of great influence since 1980, although some limitations have been pointed out which have led to modifications.[16] In this model, the basal ganglia normally exert a constant inhibitory influence on a wide range of motor systems, preventing them from becoming active at inappropriate times. When a decision is made to perform a particular action, inhibition is reduced for the required motor system, thereby releasing it for activation. Dopamine acts to facilitate this release of inhibition, so high levels of dopamine function tend to promote motor activity, while low levels of dopamine function, such as occur in PD, demand greater exertions of effort for any given movement. Thus the net effect of dopamine depletion is to produce hypokinesia, an overall reduction in motor output.[16] Drugs that are used to treat PD, conversely, may produce excessive dopamine activity, allowing motor systems to be activated at inappropriate times and thereby producing dyskinesias.[16]

Brain cell death

There is speculation of several mechanisms by which the brain cells could be lost.[19] One mechanism consists of an abnormal accumulation of the protein alpha-synuclein bound to ubiquitin in the damaged cells. This insoluble protein accumulates inside neurones forming inclusions called Lewy bodies.[4][20] According to the Braak staging, a classification of the disease based on pathological findings, Lewy bodies first appear in the olfactory bulb, medulla oblongata and pontine tegmentum, with individuals at this stage being asymptomatic. As the disease progresses, Lewy bodies later develop in the substantia nigra, areas of the midbrain and basal forebrain, and in a last step the neocortex.[4] These brain sites are the main places of neuronal degeneration in PD; however, Lewy bodies may not cause cell death and they may be protective.[19][20] In patients with dementia, a generalized presence of Lewy bodies is common in cortical areas. Neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques, characteristic of Alzheimer's disease, are not common unless the person is demented.[17]

Other cell-death mechanisms include proteosomal and lysosomal system dysfunction and reduced mitochondrial activity.[19] Iron accumulation in the substantia nigra is typically observed in conjunction with the protein inclusions. It may be related to oxidative stress, protein aggregation and neuronal death, but the mechanisms are not fully understood.[21]

Diagnosis

A physician will diagnose Parkinson's disease from the medical history and a neurological examination.[1] There is no lab test that will clearly identify the disease, but brain scans are sometimes used to rule out disorders that could give rise to similar symptoms. Patients may be given levodopa and resulting relief of motor impairment tends to confirm diagnosis. The finding of Lewy bodies in the midbrain on autopsy is usually considered proof that the patient suffered from Parkinson's disease. The progress of the illness over time may reveal it is not Parkinson's disease, and some authorities recommend that the diagnosis be periodically reviewed.[1][22]

Other causes that can secondarily produce a parkinsonian syndrome are Alzheimer's disease, multiple cerebral infarction and drug-induced parkinsonism.[22] Parkinson plus syndromes such as progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy must be ruled out.[1] Anti-Parkinson's medications are typically less effective at controlling symptoms in Parkinson plus syndromes.[1] Faster progression rates, early cognitive dysfunction or postural instability, minimal tremor or symmetry at onset may indicate a Parkinson plus disease rather than PD itself.[23] Genetic forms are usually classified as PD, although the terms familial Parkinson's disease and familial parkinsonism are used for disease entities with an autosomal dominant or recessive pattern of inheritance.[2]

Medical organizations have created diagnostic criteria to ease and standardize the diagnostic process, especially in the early stages of the disease. The most widely known criteria come from the UK Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank and the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.[1] The PD Society Brain Bank criteria require slowness of movement (bradykinesia) plus either rigidity, resting tremor, or postural instability. Other possible causes for these symptoms need to be ruled out. Finally, three or more of the following features are required during onset or evolution: unilateral onset, tremor at rest, progression in time, asymmetry of motor symptoms, response to levodopa for at least five years, clinical course of at least ten years and appearance of dyskinesias induced by the intake of excessive levodopa.[1] Accuracy of diagnostic criteria evaluated at autopsy is 75–90%, with specialists such as neurologists having the highest rates.[1]

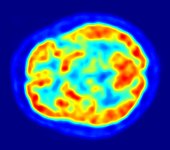

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans of people with PD usually appear normal.[24] These techniques are nevertheless useful to rule out other diseases that can be secondary causes of parkinsonism, such as basal ganglia tumors, vascular pathology and hydrocephalus.[24] A specific technique of MRI, diffusion MRI, has been reported to be useful at discriminating between typical and atypical parkinsonism, although its exact diagnostic value is still under investigation.[24] Dopaminergic function in the basal ganglia can be measured with the help of different PET and SPECT radiotracers. Examples are ioflupane (123I) (trade name DaTSCAN) and iometopane (Dopascan) for SPECT or fludeoxyglucose (18F) for PET.[24] A pattern of reduced dopaminergic activity in the basal ganglia can aid in diagnosing PD.[24]

Management

There is no cure for Parkinson's disease, but medications, surgery and multidisciplinary management can provide relief from the symptoms. The main families of drugs useful for treating motor symptoms are levodopa (usually combined with a dopa decarboxylase inhibitor or COMT inhibitor), dopamine agonists and MAO-B inhibitors.[25] The stage of the disease determines which group is most useful. Two stages are usually distinguished: an initial stage in which the individual with PD has already developed some disability for which he needs pharmacological treatment, then a second stage in which an individual develops motor complications related to levodopa usage.[25] Treatment in the initial stage aims for an optimal tradeoff between good symptom control and side-effects resulting from enhancement of dopaminergic function. The start of levodopa (or L-DOPA) treatment may be delayed by using other medications such as MAO-B inhibitors and dopamine agonists, in the hope of delaying the onset of dyskinesias.[25] In the second stage the aim is to reduce symptoms while controlling fluctuations of the response to medication. Sudden withdrawals from medication or overuse have to be managed.[25] When medications are not enough to control symptoms, surgery and deep brain stimulation can be of use.[26] In the final stages of the disease, palliative care is provided to enhance quality of life.[27]

Levodopa

Levodopa has been the most widely used treatment for over 30 years.[25] L-DOPA is converted into dopamine in the dopaminergic neurons by dopa decarboxylase.[25] Since motor symptoms are produced by a lack of dopamine in the substantia nigra, the administration of L-DOPA temporarily diminishes the motor symptoms.[25]

Only 5–10% of L-DOPA crosses the blood-brain barrier. The remainder is often metabolized to dopamine elsewhere, causing a variety of side effects including nausea, dyskinesias and joint stiffness.[25] Carbidopa and benserazide are peripheral dopa decarboxylase inhibitors,[25] which help to prevent the metabolism of L-DOPA before it reaches the dopaminergic neurons, therefore reducing side effects and increasing bioavailability. They are generally given as combination preparations with levodopa.[25] Existing preparations are carbidopa/levodopa (co-careldopa) and benserazide/levodopa (co-beneldopa). Levodopa has been related to dopamine dysregulation syndrome, which is a compulsive overuse of the medication, and punding.[12] There are controlled release versions of levodopa in the form intravenous and intestinal infusions that spread out the effect of the medication. These slow-release levodopa preparations have not shown an increased control of motor symptoms or motor complications when compared to immediate release preparations.[25][28]

Tolcapone inhibits the COMT enzyme, which degrades dopamine, thereby prolonging the effects of levodopa.[25] It has been used to complement levodopa; however, its usefulness is limited by possible side effects such as liver damage.[25] A similarly effective drug, entacapone, has not been shown to cause significant alterations of liver function.[25] Licensed preparations of entacapone contain entacapone alone or in combination with carbidopa and levodopa.[25]

Levodopa preparations lead in the long term to the development of motor complications characterized by involuntary movements called dyskinesias and fluctuations in the response to medication.[25] When this occurs a person with PD can change from phases with good response to medication and few symptoms ("on" state), to phases with no response to medication and significant motor symptoms ("off" state).[25] For this reason, levodopa doses are kept as low as possible while maintaining functionality.[25] Delaying the initiation of therapy with levodopa by using alternatives (dopamine agonists and MAO-B inhibitors) is common practice.[25] A former strategy to reduce motor complications was to withdraw L-DOPA medication for some time. This is discouraged now, since it can bring dangerous side effects such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[25] Most people with PD will eventually need levodopa and later develop motor side effects.[25]

Dopamine agonists

Several dopamine agonists that bind to dopaminergic post-synaptic receptors in the brain have similar effects to levodopa.[25] These were initially used for individuals experiencing on-off fluctuations and dyskinesias as a complementary therapy to levodopa; they are now mainly used on their own as an initial therapy for motor symptoms with the aim of delaying motor complications.[25][29] When used in late PD they are useful at reducing the off periods.[25] Dopamine agonists include bromocriptine, pergolide, pramipexole, ropinirole, piribedil, cabergoline, apomorphine and lisuride.

Dopamine agonists produce significant, although usually mild, side effects including drowsiness, hallucinations, insomnia, nausea and constipation.[25] Sometimes side effects appear even at a minimal clinically effective dose, leading the physician to search for a different drug.[25] Compared with levodopa, dopamine agonists may delay motor complications of medication use but are less effective at controlling symptoms.[25] Nevertheless, they are usually effective enough to manage symptoms in the initial years.[2] They tend to be more expensive than levodopa.[2] Dyskinesias due to dopamine agonists are rare in younger people who have PD, but along with other side effects, become more common with age at onset.[2] Thus dopamine agonists are the preferred initial treatment for earlier onset, as opposed to levodopa in later onset.[2] Agonists have been related to a impulse control disorders (such as compulsive sexual activity and eating, and pathological gambling and shopping) even more strongly than levodopa.[12]

Apomorphine, a non-orally administered dopamine agonist, may be used to reduce off periods and dyskinesia in late PD.[25] It is administered by intermittent injections or continuous subcutaneous infusions.[25] Since secondary effects such as confusion and hallucinations are common, individuals receiving apomorphine treatment should be closely monitored.[25] Two dopamine agonists that are administered through skin patches (lisuride and rotigotine) have been recently found to be useful for patients in initial stages and preliminary positive results has been published on the control of off states in patients in the advanced state.[28]

MAO-B inhibitors

MAO-B inhibitors (selegiline and rasagiline) increase the level of dopamine in the basal ganglia by blocking its metabolism. They inhibit monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) which breaks down dopamine secreted by the dopaminergic neurons. The reduction in MAO-B activity results in increased L-DOPA in the striatum.[25] Like dopamine agonists, MAO-B inhibitors used as monotherapy improve motor symptoms and delay the need for levodopa in early disease, but produce more adverse effects and are less effective than levodopa. There are few studies of their effectiveness in the advanced stage, although results suggest that they are useful to reduce fluctuations between on and off periods.[25] An initial study indicated that selegiline in combination with levodopa increased the risk of death, but this was later disproven.[25]

Other drugs

Other drugs such as amantadine and anticholinergics may be useful as treatment of motor symptoms. However, the evidence supporting them lacks quality, so they are not first choice treatments.[25] In addition to motor symptoms, PD is accompanied by a diverse range of symptoms. A number of drugs have been used to treat some of these problems.[30] Examples are the use of clozapine for psychosis, cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia, and modafinil for daytime sleepiness.[30][31]

Surgery and deep brain stimulation

Treating motor symptoms with surgery was once a common practice, but since the discovery of levodopa, the number of operations has declined.[32] Studies in the past few decades have led to great improvements in surgical techniques, so that surgery is again being used in people with advanced PD for whom drug therapy is no longer sufficient.[32] Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is the most commonly used surgical treatment. Other surgical therapies involve the formation of lesions in specific subcortical areas (a technique known as pallidotomy).[32] DBS involves the implantation of a medical device called a brain pacemaker, which sends electrical impulses to specific parts of the brain. Target areas for DBS or lesions include the thalamus, the globus pallidus or the subthalamic nucleus.[32] DBS is recommended for people who have PD who suffer from motor fluctuations and tremor inadequately controlled by medication, or to those who are intolerant to medication, as long as they do not have severe neuropsychiatric problems.[26]

Rehabilitation

There is some evidence that speech or mobility problems can improve with rehabilitation, although studies are scarce and of low quality.[33][34] Regular physical exercise with or without physiotherapy can be beneficial to maintain and improve mobility, flexibility, strength, gait speed, and quality of life.[34] Exercise may improve constipation.[14] One of the most widely practiced treatments for speech disorders associated with Parkinson's disease is the Lee Silverman voice treatment (LSVT).[33][35] Speech therapy and specifically LSVT may improve speech.[33] Occupational therapy (OT) aims to promote health and quality of life by helping people with the disease to participate in as many of their daily living activities as possible.[33] There have been few studies on the effectiveness of OT and their quality is poor, although there is some indication that it may improve motor skills and quality of life for the duration of the therapy.[33][36]

Diet

Muscles and nerves that control the digestive process may be affected by PD, resulting in constipation and gastroparesis (food remaining in the stomach for a longer period of time than normal).[14] A balanced diet, based on periodical nutritional assessments, is recommended and should be designed to avoid weight loss or gain and minimize consequences of gastrointestinal dysfunction.[14] As the disease advances, swallowing difficulties (dysphagia) may appear. In such cases it may be helpful to use thickening agents for liquid intake and an upright posture when eating, both measures reducing the risk of choking. Gastrostomy to deliver food directly into the stomach is possible in severe cases.[14]

Levodopa and proteins use the same transportation system in the intestine and the blood-brain barrier, thereby competing for access.[14] When they are taken together, this results in a reduced effectiveness of the drug.[14] Therefore, when levodopa is introduced, excessive protein consumption is discouraged and well balanced Mediterranean diet is recommended. In advanced stages, additional intake of low-protein products such as bread or pasta is recommended for similar reasons.[14] To minimize interaction with proteins, levodopa should be taken 30 minutes before meals.[14] At the same time, regimens for PD restrict proteins during breakfast and lunch, allowing protein intake in the evening.[14]

Palliative care

Palliative care is often required in the final stages of the disease when all other treatment strategies have become ineffective. The aim of palliative care is to maximize the quality of life for the person with the disease and those surrounding him or her. Some central issues of palliative care are: care in the community while adequate care can be given there, reducing or withdrawing drug intake to reduce drug side effects, preventing pressure ulcers by management of pressure areas of inactive patients, and facilitating end-of-life decisions for the patient as well as involved friends and relatives.[27]

Other treatments

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation temporarily improves levodopa-induced dyskinesias.[37] Its usefulness in PD is an open research topic.[38] Several nutrients have been proposed as possible treatments; however there is no strong evidence that vitamins or food additives improve symptoms.[39] There is not enough evidence to substantiate that acupuncture and practice of Qigong, or Tai chi, have any effect on symptoms.[40][41][42] Fava beans and velvet beans are natural sources of levodopa and are eaten by many people with PD. While they have shown some effectiveness in clinical trials,[43] their intake is not free of risks. Life-threatening adverse reactions have been described, such as the neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[44][45]

Prognosis

PD invariably progresses with time. Motor symptoms, if not treated, advance aggressively in the early stages of the disease and more slowly later. Untreated, individuals are expected to lose independent ambulation after an average of eight years and be bedridden after ten years.[46] However, it is uncommon to find untreated people nowadays. Medication has improved the prognosis of motor symptoms, while at the same time it is a new source of disability due to the undesired effects of levodopa after years of use.[46] In people taking levodopa, the progression time of symptoms to a stage of high dependency from caregivers may be over 15 years.[46] However, it is hard to predict what course the disease will take for a given individual.[46] Age is the best predictor of disease progression.[19] The rate of motor decline is greater in those with less impairment at the time of diagnosis, while cognitive impairment is more frequent in those who are over 70 years of age at symptom onset.[19]

Since current therapies improve motor symptoms, disability at present is mainly related to non-motor features of the disease.[19] Nevertheless, the relationship between disease progression and disability is not linear. Disability is initially related to motor symptoms and particularly motor complications, which appear in up to 50% of individuals after 5 years of levodopa usage.[46] As the disease advances, disability is more related to motor symptoms that do not respond adequately to medication, such as swallowing and speech difficulties and gait and balance problems.[46] Finally, after ten years most people with the disease have autonomic disturbances, sleep problems, mood alterations and cognitive decline.[46] All of them, but specially the latter, greatly increase disability.[19][46]

The life expectancy of people with PD is lower than for people who do not have the disease.[46] Mortality ratios are around twice those of unaffected people.[46] Cognitive decline and dementia, old age at onset, a more advanced disease state and presence of swallowing problems are all mortality risk factors. On the other hand a disease pattern mainly characterized by tremor as opposed to rigidity predicts an improved survival.[46] One specific cause of death twice as common in individuals with PD as in the healthy population is aspiration pneumonia.[46]

Epidemiology

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer's disease.[47] Epidemiology studies estimate the prevalence (proportion in a population at a given time) of PD to be 0.3% of the whole population in industrialized countries. PD is more common in the elderly and prevalence rises from 1% in those over 60 years of age to 4% of the population over 80.[47] The mean age of onset is around 60 years, although 5–10% of cases, classified as young onset, begin between the ages of 20 and 50.[2] PD may be less prevalent in those of African and Asian ancestry, although this finding is disputed.[47] Some studies have proposed that it is more common in men than women, but others failed to detect any differences between the two sexes.[47] The incidence of PD is between 8 and 18 per 100,000 person–years.[47]

Many risk factors and protective factors have been proposed, sometimes in relation to theories concerning possible mechanisms of the disease, however none have been conclusively related to PD by empirical evidence. When epidemiological studies have been carried out in order to test the relationship between a given factor and PD, they have frequently been biased and their results have in some cases been contradictory.[47] The most frequently replicated relationships are an increased risk of PD in those exposed to pesticides and a reduced risk in smokers.[47]

Risk factors

Injections of the synthetic neurotoxin MPTP produce a range of symptoms similar to those of PD as well as selective damage to the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. This observation has led to theorizing that exposure to some environmental toxins may increase the risk of having PD.[47] Exposure to toxins that have been consistently related to the disease can double the risk of PD and include certain pesticides, such as rotenone or paraquat, and herbicides, such as Agent Orange.[47][48][49] Indirect measures of exposure, such as living in rural environments, have been found to increase the risk of PD.[49] Heavy metals exposure has been proposed to be a risk factor, through possible accumulation in the substantia nigra; however, studies on the issue have been inconclusive.[47]

Recent studies have suggested that exposure to the amphetamines Benzedrine (Amedra Pharmaceuticals) and Dexedrine (GlaxoSmithKline) is associated with a roughly 60% boost in the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. [50]

Protective factors

Smoking has been related to a reduced risk of having PD. Smokers risk of having PD may be reduced down to a third when compared to non smokers.[47] The basis for this effect is not known, but possibilities include an effect of nicotine as a dopamine stimulant.[47] Caffeine consumption also protects against PD.[51] Antioxidants, such as vitamin C and D, have been proposed to protect against the disease but results of studies have been contradictory and no positive effect has been proven.[47] The results regarding fat and fatty acids have been contradictory, with various studies reporting protective effects, risk-enhancing effects, and no effects respectively.[47] Finally there have been preliminary indications of a possible protective role of estrogens and anti-inflammatory drugs.[47]

History

Several early sources, including an Egyptian papyrus, an Ayurvedic medical treatise, the Bible, or Galen's writings, describe symptoms resembling those of PD.[52] After Galen there are no references unambiguously related to PD until the 17th century.[52] In this and the following century several authors wrote about elements of the disease, including Sylvius, Gaubius, Hunter and Chomel.[52][53][54]

In 1817 an English doctor, James Parkinson, published his essay reporting six cases of paralysis agitans.[55] An Essay on the Shaking Palsy described the characteristic resting tremor, abnormal posture and gait, paralysis and diminished muscle strength, and the way that the disease progresses over time.[55][56] Early neurologists who made further additions to the knowledge of the disease include Trousseau, Gowers, Kinnier Wilson and Erb, and most notably Jean-Martin Charcot, whose studies between 1868 and 1881 were a landmark in the understanding of the disease.[55] Among other advances, he made the distinction between rigidity, weakness and bradykinesia.[55] He also championed the renaming of the disease in honor of Parkinson.[55]

In 1912 Frederic Lewy described microscopic particles in affected brains, later named "Lewy bodies".[55] In 1919 Konstantin Tretiakoff reported that the substantia nigra was the main cerebral structure affected, but this finding was not widely accepted until it was confirmed by further studies published by Rolf Hassler in 1938.[55] The underlying biochemical changes in the brain were identified in the 1950s, due largely to the work of Arvid Carlsson on the neurotransmitter dopamine and its role on PD.[57] That alpha-synuclein is the main component of Lewy bodies was discovered in 1997.[20]

Anticholinergics and surgery were the only treatments until the arrival of levodopa, which reduced their use dramatically.[53][58] Levodopa was first synthesized in 1911 by Casimir Funk, but it received little attention until the mid 20th century.[57] It entered clinical practice in 1967 and brought about a revolution in the management of PD.[57][59] By the late 1980s deep brain stimulation emerged as a possible treatment.[60]

Research directions

There is little prospect of dramatic new PD treatments expected in a short time frame.[61] Currently active research directions include the search for new animal models of the disease and studies of the potential usefulness of gene therapy, stem cell transplants and neuroprotective agents.[19]

Animal models

PD is not known to occur naturally in any species other than humans, although animal models which show some features of the disease are used in research. The appearance of parkinsonian symptoms in a group of drug addicts in the early 1980s who consumed a contaminated batch of the synthetic opiate MPPP led to the discovery of the chemical MPTP as an agent that causes a parkinsonian syndrome in non-human primates as well as in humans.[62] Other predominant toxin-based models employ the insecticide rotenone, the herbicide paraquat and the fungicide maneb.[63] Models based on toxins are most commonly used in primates. Transgenic rodent models that replicate various aspects of PD have been developed.[64]

Gene therapy

Gene therapy involves the use of a non-infectious virus to shuttle a gene into a part of the brain. The gene used leads to the production of an enzyme which helps to manage PD symptoms or protects the brain from further damage.[19][65] In 2010 there were four clinical trials using gene therapy in PD.[19] There have not been important adverse effects in these trials although the clinical usefulness of gene therapy is still unknown.[19]

Neuroprotective treatments

Investigations on neuroprotection are at the forefront of PD research. Several molecules have been proposed as potential treatments.[19] However, none of them have been conclusively demonstrated to reduce degeneration.[19] Agents currently under investigation include anti-apoptotics (TCH346, CEP-1347), antiglutamatergics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (selegiline, rasagiline), promitochondrials (coenzyme Q10, creatine), calcium channel blockers (isradipine) and growth factors (GDNF).[19] Preclinical research also targets alpha-synuclein.[61]

Neural transplantation

Since early in the 1980s, fetal, porcine, carotid or retinal tissues have been used in cell transplants, in which dissociated cells are injected into the substantia nigra in the hope that they will incorporate themselves into the brain in a way that replaces the dopamine cells that have been lost.[19] Although there was initial evidence of mesencephalic dopamine-producing cell transplants being beneficial, double-blind trials to date indicate that cell transplants produce no demonstrable long-term benefit.[19] An additional significant problem was the excess release of dopamine by the transplanted tissue, leading to dystonias.[66] Stem cell transplants are a recent main research target, because stem cells are easy to manipulate and stem cells transplanted into the brains of rodents and monkeys have been found to survive and to reduce behavioral abnormalities.[19][67] Nevertheless, use of fetal stem cells is controversial.[19] It has been proposed that effective treatments may be developed in a less controversial way by use of induced pluripotent stem cells taken from adults.[19]

Society and culture

Cost

The costs of PD to society are high, but difficult to calculate exactly due to methodological difficulties in research and differences between countries.[68] The annual cost in the UK is estimated to be between 449 million and 3.3 billion pounds, while the cost per patient per year in the US is probably around $10,000 and the total burden around 23 billion dollars.[68] The largest share of direct cost comes from inpatient care and nursing homes, while the share coming from medications is substantially lower.[68] Indirect costs are high, due to reduced productivity and the burden on caregivers.[68] In addition to economic costs, PD reduces quality of life of those with the disease and their caregivers.[68]

Advocacy

April 11, the birthday of James Parkinson, has been designated as the world's Parkinson's disease day.[55][69] A red tulip was chosen by several international organizations as the symbol of the disease in 2005: it represents the James Parkinson Tulip cultivar, registered in 1981 by a Dutch horticulturalist.[69] Advocacy organizations on the disease include the Parkinson's Disease Foundation, which has provided more than $85 million for research and $34 million for education and advocacy programs since its founding in 1957 by William Black;[70][71] the American Parkinson Disease Association, founded in 1961;[72] and the European Parkinson's Disease Association, founded in 1992.[73]

Notable cases

Among the many famous people with PD, one who has greatly increased the public awareness of the disease has been actor Michael J. Fox. Fox was diagnosed in 1991 when he was 30, but kept his condition secret from the public for seven years.[74] He has written two autobiographic books in which his fight against the disease plays a major role,[75] and appeared before the United States Congress without medication to illustrate the effects of the disease.[75] The Michael J. Fox Foundation aims to develop a cure for Parkinson's disease. In recent years it has been the major Parkinson's fundraiser in the US, providing 140 million dollars in research funding between 2001 and 2008.[75] Fox's work led him to be named one of the 100 people "whose power, talent or moral example is transforming the world" in 2007 by the Time magazine,[74] and he received an honorary doctorate in medicine from Karolinska Institutet for his contributions to research in Parkinson's disease.[76] Another foundation that supports Parkinson's research was established by professional cyclist Davis Phinney.[77] The Davis Phinney Foundation strives to improve the lives of those living with Parkinson's disease by providing them with information and tools.[78] Muhammad Ali has been called the "world's most famous Parkinson's patient".[79] He was 42 at diagnosis although he already showed signs of Parkinson's when he was 38.[80] Nevertheless, whether he truly has PD or a parkinsonian syndrome due to boxing is still an open question.[80][81]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Jankovic J (2008). "Parkinson's disease: clinical features and diagnosis". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 79 (4): 368–76. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045. PMID 18344392.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Samii A, Nutt JG, Ransom BR (2004). "Parkinson's disease". Lancet. 363 (9423): 1783–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16305-8. PMID 15172778.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schrag A (2007). "Epidemiology of movement disorders". In Tolosa E, Jankovic JJ (ed.). Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 50–66. ISBN 0-7817-7881-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davie CA (2008). "A review of Parkinson's disease". Br. Med. Bull. 86: 109–27. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldn013. PMID 18398010.

- ^ a b Galpern WR, Lang AE (2006). "Interface between tauopathies and synucleinopathies: a tale of two proteins". Ann. Neurol. 59 (3): 449–58. doi:10.1002/ana.20819. PMID 16489609.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Aarsland D, Londos E, Ballard C (2009). "Parkinson's disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies: different aspects of one entity". Int. Psychogeriatr. 21 (2): 216–9. doi:10.1017/S1041610208008612. PMID 19173762.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Cooper G, Eichhorn G, Rodnitzky RL (2008). "Parkinson's disease". In Conn PM (ed.). Neuroscience in medicine. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 508–512. ISBN 978-1-60327-454-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Jahanshahi M, Krack P; et al. (2009). "Initial clinical manifestations of Parkinson's disease: features and pathophysiological mechanisms". Lancet Neurol. 8 (12): 1128–39. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70293-5. PMID 19909911.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Banich MT, Compton RJ (2011). "Motor control". Cognitive neuroscience. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage learning. pp. 108–44. ISBN 0-8400-3298-6.

- ^ Fung VSC, Thompson PD (2007). "Rigidity and spasticity". In Tolosa E, Jankovic JJ (ed.). Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 504–13. ISBN 0-7817-7881-6.

- ^ a b c d e Caballol N, Martí MJ, Tolosa E (2007). "Cognitive dysfunction and dementia in Parkinson disease". Mov. Disord. 22 Suppl 17: S358–66. doi:10.1002/mds.21677. PMID 18175397.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Ceravolo R, Frosini D, Rossi C, Bonuccelli U (2009). "Impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease: definition, epidemiology, risk factors, neurobiology and management". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15 Suppl 4: S111–5. doi:10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70847-8. PMID 20123548.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Friedman JH (2010). "Parkinson's disease psychosis 2010: A review article". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 16 (9): 553–60. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.05.004. PMID 20538500.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Barichella M, Cereda E, Pezzoli G (2009). "Major nutritional issues in the management of Parkinson's disease". Mov. Disord. 24 (13): 1881–92. doi:10.1002/mds.22705. PMID 19691125.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lesage S, Brice A (2009). "Parkinson's disease: from monogenic forms to genetic susceptibility factors". Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 (R1): R48–59. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp012. PMID 19297401.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Obeso JA, Rodríguez-Oroz MC, Benitez-Temino B; et al. (2008). "Functional organization of the basal ganglia: therapeutic implications for Parkinson's disease". Mov. Disord. 23 Suppl 3: S548–59. doi:10.1002/mds.22062. PMID 18781672.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Dickson DV (2007). "Neuropathology of movement disorders". In Tolosa E, Jankovic JJ (ed.). Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 271–83. ISBN 0-7817-7881-6.

- ^ Jubault T, Brambati SM, Degroot C; et al. (2009). "Regional brain stem atrophy in idiopathic Parkinson's disease detected by anatomical MRI". PLoS ONE. 4 (12): e8247. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008247. PMC 2784293. PMID 20011063.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Goetz CG; et al. (2010). "Missing pieces in the Parkinson's disease puzzle". Nat. Med. 16 (6): 653–61. doi:10.1038/nm.2165. PMID 20495568.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Schulz-Schaeffer WJ (2010). "The synaptic pathology of alpha-synuclein aggregation in dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease and Parkinson's disease dementia". Acta Neuropathol. 120 (2): 131–43. doi:10.1007/s00401-010-0711-0. PMC 2892607. PMID 20563819.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hirsch EC (2009). "Iron transport in Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15 Suppl 3: S209–11. doi:10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70816-8. PMID 20082992.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, ed. (2006). "Diagnosing Parkinson's Disease". Parkinson's Disease. London: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 29–47. ISBN 1-86016-283-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Poewe W, Wenning G (2002). "The differential diagnosis of Parkinson's disease". Eur. J. Neurol. 9 Suppl 3: 23–30. PMID 12464118.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Brooks DJ (2010). "Imaging approaches to Parkinson disease". J. Nucl. Med. 51 (4): 596–609. doi:10.2967/jnumed.108.059998. PMID 20351351.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, ed. (2006). "Symptomatic pharmacological therapy in Parkinson's disease". Parkinson's Disease. London: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 59–100. ISBN 1-86016-283-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b Bronstein JM, Tagliati M, Alterman RL; et al. (2011). "Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: an expert consensus and review of key issues". Arch. Neurol. 68 (2): 165. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.260. PMID 20937936.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, ed. (2006). "Palliative care in Parkinson's disease". Parkinson's Disease. London: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 147–51. ISBN 1-86016-283-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b Tolosa E, Katzenschlager R (2007). "Pharmacological management of Parkinson's disease". In Tolosa E, Jankovic JJ (ed.). Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 110–45. ISBN 0-7817-7881-6.

- ^ Goldenberg MM (2008). "Medical management of Parkinson's disease". P & T. 33 (10): 590–606. PMC 2730785. PMID 19750042.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, ed. (2006). "Non-motor features of Parkinson's disease". Parkinson's Disease. London: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 113–33. ISBN 1-86016-283-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Hasnain M, Vieweg WV, Baron MS, Beatty-Brooks M, Fernandez A, Pandurangi AK (2009). "Pharmacological management of psychosis in elderly patients with parkinsonism". Am. J. Med. 122 (7): 614–22. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.025. PMID 19559160.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, ed. (2006). "Surgery for Parkinson's disease". Parkinson's Disease. London: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 101–11. ISBN 1-86016-283-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b c d e The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, ed. (2006). "Other key interventions". Parkinson's Disease. London: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 135–46. ISBN 1-86016-283-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b Goodwin VA, Richards SH, Taylor RS, Taylor AH, Campbell JL (2008). "The effectiveness of exercise interventions for people with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Mov. Disord. 23 (5): 631–40. doi:10.1002/mds.21922. PMID 18181210.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fox CM, Ramig LO, Ciucci MR, Sapir S, McFarland DH, Farley BG (2006). "The science and practice of LSVT/LOUD: neural plasticity-principled approach to treating individuals with Parkinson disease and other neurological disorders". Semin. Speech. Lang. 27 (4): 283–99. doi:10.1055/s-2006-955118. PMID 17117354.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dixon L, Duncan D, Johnson P; et al. (2007). "Occupational therapy for patients with Parkinson's disease". Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (3): CD002813. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002813.pub2. PMID 17636709.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Koch G (2010). "rTMS effects on levodopa induced dyskinesias in Parkinson's disease patients: searching for effective cortical targets". Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 28 (4): 561–8. doi:10.3233/RNN-2010-0556. PMID 20714078.

- ^ Platz T, Rothwell JC (2010). "Brain stimulation and brain repair—rTMS: from animal experiment to clinical trials—what do we know?". Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 28 (4): 387–98. doi:10.3233/RNN-2010-0570. PMID 20714064.

- ^ Suchowersky O, Gronseth G, Perlmutter J, Reich S, Zesiewicz T, Weiner WJ (2006). "Practice Parameter: neuroprotective strategies and alternative therapies for Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 66 (7): 976–82. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000206363.57955.1b. PMID 16606908.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee MS, Lam P, Ernst E (2008). "Effectiveness of tai chi for Parkinson's disease: a critical review". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 14 (8): 589–94. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.02.003. PMID 18374620.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee MS, Ernst E (2009). "Qigong for movement disorders: A systematic review". Mov. Disord. 24 (2): 301–3. doi:10.1002/mds.22275. PMID 18973253.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lee MS, Shin BC, Kong JC, Ernst E (2008). "Effectiveness of acupuncture for Parkinson's disease: a systematic review". Mov. Disord. 23 (11): 1505–15. doi:10.1002/mds.21993. PMID 18618661.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Katzenschlager R, Evans A, Manson A; et al. (2004). "Mucuna pruriens in Parkinson's disease: a double blind clinical and pharmacological study". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 75 (12): 1672–7. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.028761. PMC 1738871. PMID 15548480.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ladha SS, Walker R, Shill HA (2005). "Case of neuroleptic malignant-like syndrome precipitated by abrupt fava bean discontinuance". Mov. Disord. 20 (5): 630–1. doi:10.1002/mds.20380. PMID 15719433.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Raguthu L, Varanese S, Flancbaum L, Tayler E, Di Rocco A (2009). "Fava beans and Parkinson's disease: useful 'natural supplement' or useless risk?". Eur. J. Neurol. 16 (10): e171. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02766.x. PMID 19678834.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Poewe W (2006). "The natural history of Parkinson's disease". J. Neurol. 253 Suppl 7: VII2–6. doi:10.1007/s00415-006-7002-7. PMID 17131223.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o de Lau LM, Breteler MM (2006). "Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease". Lancet Neurol. 5 (6): 525–35. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9. PMID 16713924.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tanner CM, Kamel F, Ross GW; et al. (2011). "Rotenone, Paraquat and Parkinson's Disease". Environ. Health Perspect. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002839. PMID 21269927.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b IOM (Institute of Medicine), ed. (2009). "Neurologic disorders". Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2008. Washington D.C.: The National Academies press. pp. 510–45. ISBN 0-309-13884-1.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Amphetamine Use Linked to Increased Parkinson's Risk". WebMD. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Costa J, Lunet N, Santos C, Santos J, Vaz-Carneiro A (2010). "Caffeine exposure and the risk of Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". J. Alzheimers Dis. 20 Suppl 1: S221–38. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-091525. PMID 20182023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c García Ruiz PJ (2004). "Prehistoria de la enfermedad de Parkinson". Neurologia (in Spanish; Castilian). 19 (10): 735–7. PMID 15568171.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|title_trans=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b Lanska DJ (2010). "Chapter 33: the history of movement disorders". Handb. Clin. Neurol. 95: 501–46. doi:10.1016/S0072-9752(08)02133-7. PMID 19892136.

- ^ Koehler PJ, Keyser A (1997). "Tremor in Latin texts of Dutch physicians: 16th–18th centuries". Mov. Disord. 12 (5): 798–806. doi:10.1002/mds.870120531. PMID 9380070.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Lees AJ (2007). "Unresolved issues relating to the shaking palsy on the celebration of James Parkinson's 250th birthday". Mov. Disord. 22 Suppl 17: S327–34. doi:10.1002/mds.21684. PMID 18175393.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Louis ED (1997). "The shaking palsy, the first forty-five years: a journey through the British literature". Mov. Disord. 12 (6): 1068–72. doi:10.1002/mds.870120638. PMID 9399240.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Fahn S (2008). "The history of dopamine and levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease". Mov. Disord. 23 Suppl 3: S497–508. doi:10.1002/mds.22028. PMID 18781671.

- ^ Guridi J, Lozano AM (1997). "A brief history of pallidotomy". Neurosurgery. 41 (5): 1169–80, discussion 1180–3. doi:10.1097/00006123-199711000-00029. PMID 9361073.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hornykiewicz O (2002). "L-DOPA: from a biologically inactive amino acid to a successful therapeutic agent". Amino Acids. 23 (1–3): 65–70. doi:10.1007/s00726-001-0111-9. PMID 12373520.

- ^ Coffey RJ (2009). "Deep brain stimulation devices: a brief technical history and review". Artif. Organs. 33 (3): 208–20. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1594.2008.00620.x. PMID 18684199.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Dimond PF (2010-08-16). "No New Parkinson Disease Drug Expected Anytime Soon". GEN news highlights. GEN-Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News.

- ^ Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I (1983). "Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis". Science. 219 (4587): 979–80. doi:10.1126/science.6823561. PMID 6823561.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cicchetti F, Drouin-Ouellet J, Gross RE (2009). "Environmental toxins and Parkinson's disease: what have we learned from pesticide-induced animal models?". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 30 (9): 475–83. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2009.06.005. PMID 19729209.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harvey BK, Wang Y, Hoffer BJ (2008). "Transgenic rodent models of Parkinson's disease". Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 101: 89–92. doi:10.1007/978-3-211-78205-7_15. PMC 2613245. PMID 18642640.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Feng, LR, Maguire-Zeiss KA (2010). "Gene Therapy in Parkinson's Disease: Rationale and Current Status". CNS Drugs. 24 (3): 177–92. doi:10.2165/11533740-000000000-00000. PMC 2886503. PMID 20155994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Redmond DE (2002). "Cellular replacement therapy for Parkinson's disease—where we are today?". The Neuroscientist. 8 (5): 457–88. doi:10.1177/107385802237703. PMID 12374430.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Stem Cell Research Aims to Tackle Parkinson's Disease". Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ^ a b c d e Findley LJ (2007). "The economic impact of Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 13 Suppl: S8–S12. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.003. PMID 17702630.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Parkinson's – 'the shaking palsy'". GlaxoSmithKline. 2009-04-01.

- ^ "Education: Joy in Giving". Time. 1960-01-18.

- ^ "About PDF". Parkinson's Disease Foundation. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ "American Parkinson Disease Association: Home". American Parkinson Disease Association, Inc. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ "About EPDA". European Parkinson's Disease Association. 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ a b Davis P (2007-05-03). "Michael J. Fox". The TIME 100. Time.

- ^ a b c Brockes E (2009-04-11). "'It's the gift that keeps on taking'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- ^ "Michael J. Fox to be made honorary doctor at Karolinska Institutet". Karolinska Institutet. 2010-03-05.

- ^ Roelofs T (2010-05-10). "Tour de France bicyclist Davis Phinney talks about life with Parkinson's Disease". The Grand Rapids Press. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- ^ Emanuel, W (2010-10-19). "Davis Phinney foundation launches exercise-focused tools to help people live well with Parkinson's" (PDF) (Press release). Davis Phinney foundation.

- ^ Brey RL (April 2006). "Muhammad Ali's Message". Neurology Now. 2 (2). American Academy of Neurology: 8.

- ^ a b Matthews W (April 2006). "Ali's Fighting Spirit". Neurology Now. 2 (2). American Academy of Neurology: 10–23.

- ^ Tauber P (1988-07-17). "Ali: Still Magic". New York Times.

External links

- Parkinson's Disease at Curlie

- Parkinson's Disease: Hope Through Research (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke)

- GeneReview/NIH/UW entry on LRRK2-Related Parkinson Disease

- European Parkinson's Disease Association