I. I. Chundrigar

This article has an unclear citation style. (November 2018) |

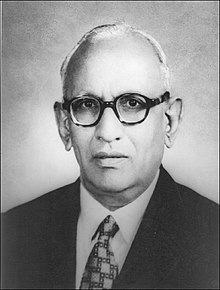

Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar ابراہیم اسماعیل چندریگر | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Pakistan | |

| In office 17 October 1957 – 11 December 1957 | |

| President | Iskander Mirza |

| Preceded by | Huseyn Suhrawardy |

| Succeeded by | Feroze Khan |

| Minister of Law and Justice | |

| In office 12 August 1955 – 9 August 1957 | |

| Prime Minister | H. S. Suhrawardy (1956-57) Muhammad Ali (1955-56) |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 12 August 1955 – 23 March 1956 Serving with H. S. Suhrawardy | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Fatima Jinnah (Appointed in 1965) |

| Governor of West Punjab | |

| In office 24 November 1951 – 2 May 1953 | |

| Chief Minister | M. Daultana |

| Preceded by | Abdur Rab Nishtar |

| Succeeded by | M. Aminuddin |

| Governor of North-West Frontier Province | |

| In office 17 February 1950 – 23 November 1951 | |

| Chief Minister | A. Q. Khan |

| Preceded by | Mohammad Khurshid |

| Succeeded by | Khwaja Shahabuddin |

| Pakistani Ambassador to Afghanistan | |

| In office 1 May 1948 – 17 February 1950 | |

| Prime Minister | Liaquat Ali Khan |

| Minister of Commerce and Trade | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 1 May 1948 | |

| Prime Minister | Liaquat Ali Khan |

| Minister of Commerce and Industry | |

| In office 2 September 1946 – 15 August 1947 | |

| President | List

|

| Vice President | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Post created |

| Succeeded by | Syama Prasad Mukherjee |

| Member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly | |

| In office 1937 – 1 September 1946 | |

| Governor | List

|

| Parliamentary group | Muslim League (Nationalist Group) |

| Constituency | Muhammadan Urban |

| Majority | Muslim League |

| President of Pakistan Muslim League | |

| In office 17 October 1957 – 11 December 1957 | |

| Preceded by | Muhammad Ali |

| Succeeded by | Nurul Amin (Took presidency in 1967) |

| President of the Supreme Court Bar Association | |

| In office 1958–1960 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar 15 September 1897[1] Godhra, Bombay Presidency, British India (Present-day Gujarat, India) |

| Died | 26 September 1960 (aged 63) London, England[2] |

| Cause of death | Haemorrhage |

| Resting place | Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan |

| Citizenship | British India (1897–47) Pakistan (1947–60) |

| Political party | Muslim League (1936-1960) |

| Children | 2 sons, including Abdullah[2] and Abu Bakr,[2] |

| Alma mater | University of Bombay (BA in Phil. and LLB) |

| Profession | Lawyer, diplomat |

| Website | I. I. Chundrigar Official website |

Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar[3] (Template:Lang-ur; 15 September 1897[1] – 26 September 1960), best known as I. I. Chundrigar, was the sixth Prime Minister of Pakistan, appointed in this capacity on 17 October 1957 until being removed due to the vote of noconfidence movement on 11 December 1957.

Trained in the constitutional law from Bombay and one of the Founding Fathers of the Dominion of Pakistan, Chundrigar's tenure is the second shortest served in the parliamentary history of Pakistan just after that of Nurul Amin who served as prime minister for 13 days. Chundrigar served only for just 55 days into his term himself.[4][5]

Biography

Early life and law practice

Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar was born in Godhra, Gujarat in India on 15 September 1897.: 106 [1][6] He was the only child of his Gujarati-speaking Chundrigar family, a Muslim community in India.[7] From his Chundriger community, he was of the Arabian descent.[8]

Chundrigar was initially schooled in Ahmedabad where he finished his matriculation and moved to Bombay for his higher studies. He went to attend Bombay University where he secured his graduation with the BA degree in philosophy, and later the LLB degree from Bombay University in 1929.[9][10][11] From 1929 till 1932, Chundrigar served as a lawyer for the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation.[12]

From 1932 until 1937, Chundrigar began practicing civil law, and moved to practice and read law at the Bombay High Court in 1937, where he established his reputation.[11] During this time, he became acquainted with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, sharing the similar ideology, work ethics, and political views.[13][7]

In 1935, Chundrigar was represented by the Muslim League to give a response to the Government of India Act 1935 introduced by the British government in India. Over the role of the Governor-General as head of state, Chundrigar notably contradicted the powers enjoyed by the Governor-General under the act introduced in 1935.[14]

From 1937 till 1946, Chundrigar practiced and read law, taking several cases on civil matters where he advocated for his clients at the Bombay High Court.[15]

Legislative career in India and Pakistan Movement

In 1936, Chundrigar joined the Muslim League and successfully participated in the provincial elections to be elected as a member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly in 1937.[10][7] He took over the Muslim League's provincial presidency based in Bombay, and successfully retained his role as the member of the legislative assembly (MLA) of the Bombay Assembly for a Muhammadan Urban constituency until 1946.[16][10]

In 1946, he was named and appointed as Commerce Minister under the presidential administrations of Viceroys of India, Archibald Wavell (1946) and Louis Mountbatten (1946-47).[10] Peter Lyon, a reader emeritus in international relations, describes Chundrigar as a "close supporter" of Mohammad Ali Jinnah in the Pakistan Movement.[17]

Public service in Pakistan

Diplomacy and governorships

After the partition of India by the act of the British Empire that laid the establishment of Pakistan, Chundrigar endorsed Liaquat Ali Khan's bid for the Premiership and was retained as the Commerce Minister in the administration of Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan on 15 August 1947.[18][19]

On 1 May 1948, Chundrigar was relieved his Commerce ministry and was appointed as the Pakistan Ambassador to Afghanistan, presenting his credentials to Afghan King Zahir Shah in Kabul.[20][21] Though, his appointment was met with favorable views in Afghanistan, Chundrigar was at odd with the Afghan government of supporting the issue of separating the country's north-west frontier, with Indian involvement as early as 1949.[22]

His tenureship remained for a short brief of time when he was recalled to Pakistan due to Foreign Office's objections, which viewed Chundrigar's inability to understand the Pashtun culture may have factor in fracturing relations between two nations.[23] In 1950, Chundrigar was appointed Governor of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, which he tenured until 1951.[10] A Cabinet reshuffle in 1951 allowed him to be appointed as the Governor of Punjab but was removed amid differences developed in 1953 with Governor-General M.G. Muhammad when he enforced martial law at the request of Prime Minister K. Nazimuddin to control violent religious riots that occurred in Lahore, Pakistan.[4]

Law ministry in Coalition administration

In 1955, Chundrigar was invited to join the central government of three-party coalition: the Awami League, Muslim League and the Republican Party.[4] He was appointed as Minister of Law and Justice.[24] During this time, he also acted as a Leader of the Opposition, opposing the mainstream agenda presented by the Republican Party.[25]

At the National Assembly, he established his reputation as more of constitutional lawyer than a politician and gained a lot of prominence in public for his arguments in favour of parliamentarianism when he pleaded the case of "Maulvi Tamizuddin vs. Federation of Pakistan".[10]

Prime Minister of Pakistan (1957)

Shortest tenure as Prime Minister

After the resignation of Prime Minister Suhrawardy in 1956, Chundrigar was nominated as the Prime Minister and was supported by Awami League, Krishak Sramik Party, Nizem-i-Islam Party, and the Republican Party.[26] However, this coalition of mixed parties weakened him to exercise his authority to run the central government, with reaching a compromise with the Republican Party led by its presidents Feroze Khan and Iskander Mirza to amend the Electoral College.[10] On 18 October 1957, Chundrigar became the Prime Minister of Pakistan oath from Chief Justice M. Munir.[26]

At the first session of the National Assembly, Chundrigar presented his plans to reform the Electoral College which was met with great parliamentary opposition even by his Cabinet ministers from the Republican Party and the Awami League.[27][26] With President Iskander Mirza and his Republican Party exploiting and manipulating the opponents of Muslim League, a successful vote of no-confidence movement in the National Assembly by Republicans and Awami Party effectively ended Chundrigar's term when he was forced to resign from his office on 11 December 1957.[27][26]

Chundrigar served the shortest term of any Prime Ministers' tenure served in Pakistan: 17 October 1957 – 11 December 1957, 55 days into his term.[5][4]

Death and reputation

In 1958, Chundrigar was appointed as president of the Supreme Court Bar Association which he remained until his death.[2] In 1960, Chundrigar traveled to Hamburg where he addressed the International Law Conference and suffered a haemorrhage while visiting in London.[2] For treatment, he was taken to the Royal Northern Hospital and suddenly died.[2] His body was brought back to Karachi in Pakistan, where he was buried in a local cemetery.[2]

In his honour, the Government of Pakistan renamed the McLeod Road in Karachi after his namesake.[7]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Biographical Encyclopedia of Pakistan. Biographical Research Institute, Pakistan. 1961. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Chundrigar dies in London". Dawn. Pakistan. 29 September 1960. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ His birth name is given as "Ismail Ibrahim Chundrigar". There's a major road in the corporate downtown in Karachi bearing his namesake as Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Road. The Bombay University confirms his name written as Ismail Ibrahim Chundrigar in their graduating listings.

- ^ a b c d Burki, Shahid Javed (2015). "§I.I. Chundrigar". Historical Dictionary of Pakistan. New York, U.S.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 136. ISBN 9781442241480. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ a b Grover, Verinder; Arora, Ranjana (1995). Political System in Pakistan: Role of military dictatorship in Pakistan politics. Deep & Deep. p. 244. ISBN 9788171007387. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Goradia, Prafull (2003). Muslim League's unfinished agenda. New Delhi: Contemporary Targett. p. 53. ISBN 9788175253766.

Jinnah Wanted All Non-Muslims To Migrate To India And All Muslims To Inhabit Pakistan. The Book Is The Story Of This Unfulfilled Dream. While Pakistan Particularly, The Western Wing Went About Ethnic Cleansing, India Failed To Encourage`Hijrat

- ^ a b c d Chundrigar, Ayesha (29 November 2012). "The Chundrigar Diaries". The Friday Times. Ayesha Chundrigar's memoirs. No. 24/41. Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan. Retrieved 24 January 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, Gujarat Population: Musalmans and Parsis, Volume IX page 72 Government Central Press, Bombay

- ^ Bombay, University of (1929). The Bombay University Calendar. Bombay, India: University of Bombay Press. p. 101. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Former Prime Minister of Pakistan: Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar". storyofpakistan.com. Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan: Nazaria-i-Pakistan Trust. 1 June 2003. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ a b Saʻīd, Aḥmad; Institute of Pakistan Historical Research (Lahore, Pakistan) (1997). Muslim India, 1857-1947: a biographical dictionary. Institute of Pakistan Historical Research. p. 111. OCLC 246043260.

- ^ Asia Who's Who. 1957. p. 90. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Rehman, Atta-ur- (1998). تحريک پاكستان كى تصويرى داستان. Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan: دوست ايسوسايٹس،. p. 321. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Newberg, Paula R. (2002). "Constituting the State". Judging the State: Courts and Constitutional Politics in Pakistan. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780521894401. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ The Asia Who's who. Pan-Asia Newspaper Alliance. 1957. p. 90. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Sho, Kuwajima (1998). Muslims, Nationalism, and the Partition: 1946 Provincial Elections in India. Mumbai, India: Manohar. p. 258. ISBN 9788173042119. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Lyon, Peter (2008). Conflict Between India and Pakistan: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-57607-712-2.

- ^ Lentz, Harris M. (2014). Heads of States and Governments Since 1945. Routledge. p. 612. ISBN 9781134264902. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ The Leader Archived 4 April 2009 at archive.today at pakistan.gov.pk

- ^ Pāshā, Aḥmad Shujāʻ (1991). Pakistan: a political profile, 1947 to 1988. Sang-e-Meel Publications. p. 88. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1979). World Scholars on Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Quaid-i-Azam University Press. p. 342.

- ^ Yunas, S. Fida (2002). Afghanistan: The Peshawar Sardars' branch of Barakzais. pp. 220–221. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Foreign Affairs Pakistan". Foreign Affairs Pakistan. 35 (7–9). Pakistan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs: 487. July 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Constituent Assembly (Legislature) of Pakistan Debates: Official Report. Manager of Publications. 1956. p. 19. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Akbar, M. K. (1997). Pakistan from Jinnah to Sharif. Mittal Publications. p. 149. ISBN 9788170996743. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d "I. I. Chundrigar Becomes Prime Minister". storyofpakistan.com. Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan: Nazaria-i-Pakistan Trust. 1 June 2003. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ a b Zakaria, Nasim (1958). Parliamentary Government in Pakistan. New Publishers. p. 62. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

External links

- 1897 births

- 1960 deaths

- People from Panchmahal district

- Politicians from Ahmedabad

- University of Mumbai alumni

- 20th-century Indian philosophers

- 20th-century Indian lawyers

- All India Muslim League members

- Leaders of the Pakistan Movement

- Pakistani people of Gujarati descent

- Pakistani people of Arab descent

- People from Karachi

- First Pakistani Cabinet

- Pakistani diplomats

- Ambassadors of Pakistan to Afghanistan

- Governors of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

- Pakistani lawyers

- Governors of Punjab, Pakistan

- Ambassadors of Pakistan to Turkey

- Pakistan Muslim League politicians

- Pakistani legal scholars

- Lawyers from Karachi

- Law Ministers of Pakistan

- Pakistani philosophers

- Prime Ministers of Pakistan

- University of Karachi people

- Members of the Pakistan Philosophical Congress

- Deaths from bleeding

- Scholars from Ahmedabad