Luba-Kasai language

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2013) |

| Tshiluba | |

|---|---|

| Cilubà[1] (Tshilubà) | |

| Native to | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Region | Kasai |

| Ethnicity | Baluba-Kasai (Bena-kasai) |

Native speakers | (6.3 million Cilubaphones cited 1991)[2] |

| Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | lua |

| ISO 639-3 | lua |

| Glottolog | luba1249 |

L.31[3] | |

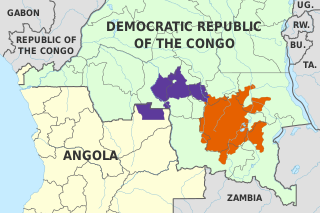

Location of speakers:

Luba-Kasai

| |

| Pidgin Chiluba | |

|---|---|

| Native to | DR Congo |

Native speakers | None |

Luba-based pidgin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

L.30A[3] | |

Luba-Kasai, also known as Cilubà or Tshilubà,[4] Luba-Lulua,[5][6] is a Bantu language (Zone L) of Central Africa and a national language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, alongside Lingala, Swahili, and Kikongo ya leta.

An eastern dialect is spoken by the Luba people of the East Kasai Region and a western dialect by the Lulua people of the West Kasai Region. The total number of speakers was estimated at 6.3 million in 1991.

Within the Zone L Bantu languages, Luba-Kasai is one of a group of languages which form the "Luba" group, together with Kaonde (L40), Kete (L20), Kanyok, Luba-Katanga (KiLuba), Sanga, Zela and Bangubangu. The L20, L30 and L60 languages are also grouped as the Luban languages within Zone L Bantu.

Geographic distribution and dialects

Tshiluba is chiefly spoken in a large area in the Kasaï Occidental and Kasaï Oriental provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, the differences in Tshiluba within the area are minor, consisting mostly of differences in tones and vocabulary, and speakers easily understand one another. Both dialects have subdialects.

Additionally, there is also a pidginised variety of Tshiluba,[3] especially in cities, where the everyday spoken Tshiluba is enriched with French words and even words from other languages, such as Lingala or Swahili. Nevertheless, it is not a typical form of a pidgin since it is not common to everyone but changes its morphology and the quantity and degree to which words from other languages are used. Its form changes depending on who speaks it and varies from city to city and social class to social class. However, people generally speak the regular Tshiluba language in their daily lives, rather than pidgin.

The failure of the language to be taught at school has resulted in the replacement of native words by French words for the most part. For instance, people speaking generally count in French, rather than Tshiluba. The situation of French and Tshiluba being used simultaneously made linguists mistakenly think that the language had been pidginised.[citation needed]

Vocabulary

| Western dialects | Eastern dialects | English |

|---|---|---|

| meme | mema | me |

| ne | ni | with |

| nzolo/nsolo | nzolu | chicken |

| bionso | bionsu | everything |

| luepu | mukela (e) | salt |

| kapia | mudilu | fire |

| bidia | nshima | fufu |

| malaba | makelela | yesterday/ tomorrow |

| lupepe | luhepa | wind |

| Mankaji (shi)/tatu mukaji | tatu mukaji | aunty |

| bimpe | bimpa | well/good |

Alphabet

Luba-Kasai uses the Latin alphabet, with the digraphs ng, ny and sh but without the letters q, r and x:[7]

Phonology

Tshiluba has a 5 vowel system with vowel length:

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open | a aː |

The chart shows the consonants of Tshiluba.

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Post-alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | |||||

| vl. prenasal | ᵐp | ⁿt | ⁿtʃ | ᵑk | |||

| vd. prenasal | ᵐb | ⁿd | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | (ɸ) | f | s | ʃ | h | |

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ||||

| vl. prenasal | ᶬf | ⁿs | ⁿʃ | ||||

| vd. prenasal | ᶬv | ⁿz | ⁿʒ | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Approximant | l | j | w | ||||

- /p/ may also have the sound [ɸ].

- If a /d/ is preceding an /i/, it may also be pronounced as an affricate sound [dʒ].

Sample text

According to The Rosetta Project,[8] Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights translates to:

- Bantu bonsu badi baledibwa badikadile ne badi ne makokeshi amwe. Badi ne lungenyi lwa bumuntu ne kondo ka moyo, badi ne bwa kwenzelangana malu mu buwetu.

- "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

According to Learn Tshiluba (Mofeko):

- Mukayi wuani udi mu bujimi

- "My wife is on the farm"[9]

- Mulunda wanyi mujikija kalasa Uenda mu tshidimu tshishala

- "My friend completed his/her studies last year" [10]

References

- ^ "Cilubà" is Standard Orthography, pronounced like "Chilubà" and "Tshilubà".

- ^ Tshiluba at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Jouni Filip Maho, 2009. New Updated Guthrie List Online

- ^ The prefix tshi or ci, depending on the spelling used, is used for the noun class used with language names

- ^ "Luba-Lulua" combines the name "Luba" (in the strictest sense, Luba Lubilanji people) and "Lulua" (Beena Luluwa people), as in "the Luba-Lulua conflict".

- ^ Ethnologue.com also indicates the name "Beena Lulua" but that is the name of the Beena Luluwa people, or the name "Luva" but that is a synonym of Kiluba (Kiluva), a different Luban language, which has a fricative bilabial between vowels.

- ^ "Tshiluba language and alphabet". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- ^ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Rosetta Project: A Long Now Foundation Library of Human Language (no author). (2010). https://archive.org/details/rosettaproject_lua_undec-1

- ^ Akindipe, Tola; Yamba, Francisco; Tshiama, Veronica. "Family in Tshiluba". Learn Tshiluba (Mofeko).

- ^ Akindipe, Tola; Yamba, Francisco; Tshiama, Veronica. "Days in Tshiluba". Learn Tshiluba (Mofeko).

- Samuel Phillips Verner (1899). Mukanda wa Chiluba. Spottiswoode. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

Bibliography

- Stappers, Leo. Tonologische bijdrage tot de studie van het werkwoord in het tshiluba. 1949. Mémoires (Institut royal colonial belge. Section des sciences morales et politiques). Collection in-8o ; t. 18, fasc. 4.

- de Schryver, Gilles-Maurice. Cilubà Phonetics: Proposals for a 'Corpus-Based Phonetics from Below' Approach. 1999. Research Centre of African Languages and Literatures, University of Ghent.

- DeClercq, P. Grammaire de la langue des bena-lulua. 1897. Polleunis et Ceuterick.

- Muyunga, Yacioko Kasengulu. 1979. Lingala and Ciluba speech audiometry. Kinshasa: Presses Universitaires du Zaïre pour l'Université Nationale du Zaïre (UNAZA).

- Kabuta, Ngo. Loanwords in Cilubà. 2012. University of Ghent, Belgium.

- Willems, Em. Het Tshiluba van Kasayi voor beginnelingen. 1943. Sint Norbertus.

External links

- Tola Akindipe, Veronica Tshiama & Francisco Yamba, Largest online resource to learn Tshiluba (Mofeko)

- Online Cilubà - French Dictionary

- BBC News: Congo word "most untranslatable"

- PanAfrican L10n page on Luba

- Tshiluba Language and Alphabet (Omniglot)

- Tshiluba: Kasai Language