Faroese independence movement

The Faroese independence movement (Faroese: Føroyska Tjóðskaparrørslan), or the Faroese national movement (Føroyska Sjálvstýrisrørslan), is a political movement which seeks the establishment of the Faroe Islands as a sovereign state outside of Denmark.[1][2][3] Reasons for independence include the linguistic and cultural divide between Denmark and the Faroe Islands as well as their lack of proximity to one another; the Faroe Islands are about 990 km (620 mi) from Danish shores.

History of sovereignty

Pre-Denmark

Norsemen settled the islands around 800 AD, bringing the Old Norse language that evolved into the modern Faroese language. These settlers are not thought to have come directly from Scandinavia, but rather from Norse communities surrounding the Irish Sea, Northern Isles and Western Isles of Scotland, including the Shetland and Orkney islands, and Norse-Gaels. A traditional name for the islands in the Irish language, Na Scigirí, means 'the Skeggjar' and possibly refers to the Eyja-Skeggjar ('island-beards'), a nickname given to the island dwellers.

According to Færeyinga Saga, emigrants left Norway who did not approve of the monarchy of Harald I of Norway. These people settled the Faroes around the end of the 9th century.[4] It is thus officially held that the islands' Nordic language and culture are derived from the early Norwegians.[5] The islands were a possession of the Kingdom of Norway (872–1397) from 1035 until their incorporation into Denmark.

Under Danish rule

The islands have been ruled, with brief interruptions, by the Danish government since 1388, all the time being part of Norway up until 1814. Although the state of Denmark–Norway was thoroughly divided by the Treaty of Kiel of 1814, the Faroe Islands remained in Danish hands.[6] A series of discriminatory policies were put in place soon after the treaty; the Faroese parliament, the Løgting was abolished in 1816 along with the post of Prime Minister of the Faroe Islands. The aforementioned offices were replaced by a Danish judiciary.[7] Concurrently, the usage of the Faroese language was generally discouraged[vague] and Danish was instilled as the official language of the region.[citation needed]

The renewed Danish Constitution of 1849 granted the Faroese two seats in the Danish Parliament Rigsdagen.[8] 1852 saw the restoration of the Løgting, albeit merely as an 18-member consultative body to the Danish authorities.[9]

The nationalist fervor has its roots in late 19th century, established initially as a cultural/political movement which struggled for the rights of using the Faroese language in the schools, the church, in media and in the legislature. The designated start is believed to be the Christmas Meeting of 1888, which was held on December 22, 1888 in the Løgting (parliament) in Tórshavn. Two of the persons who participated were Jóannes Patursson and Rasmus Effersøe. Patursson had written a poem which Effersøe read aloud, the first line starts: Nú er tann stundin komin til handa,[10] which is often cited in support of the movement.[11] The poem was about preserving and taking care of the Faroese language; over the years it has gained a strong cultural footing in the Faroe Islands. The Faroese language was not allowed to be used in the Faroese public schools as a teaching language until 1938,[12] and in the church (Fólkakirkjan) until 1939.[13]

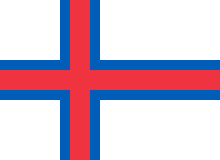

Young students who studied in Denmark played a prominent role in the nationalist movement. The Faroese Merkið flag was designed in 1919 by Faroese students in Copenhagen. Prior to the Merkið's utilization, there were other flags which some of the Faroese people identified themselves with, one was a flag featuring a ram and one was a flag with a tjaldur.[14]

Denmark was occupied by Nazi Germany as part of the Second World War on April 9, 1940. The United Kingdom, viewing the Faroe Islands as strategically valuable, began a military occupation of the islands in order to thwart further German conquest of Danish territory. This effectively put the Faroe Islands under British administration until the conclusion of the war in 1945.[15] Under British rule the Merkið was recognized as the official flag of the Faroes so that authorities could discern what vessels were Faroese fishing boats and which were hostile.

Status of autonomy

In the status quo, the Faroe Islands is an autonomous area of the Kingdom of Denmark,[16] sharing this distinction with Greenland.[17] In response to growing calls for autonomy, the Home Rule Act of the Faroe Islands was passed on March 23, 1948, cementing the latter's status as a self-governing country within The Unity of the Realm. The Act has also allowed the vast majority of domestic affairs to be ceded to the Faroese government, with the Danish government only responsible for military defence, police, justice, currency and foreign affairs.[18] The Faroe Islands are not part of the European Union. The Faroe Islands also have their own national football team and are a full member of FIFA and UEFA.

Political solutions

Organizations

Tjóðveldi = Republic

Framsókn = Progress

Fólkaflokkurin = People's Party

Miðflokkurin = Centre Party

Sjálvstýrisflokkurin = Self-Government Party

Javnaðarflokkurin = Social Democratic Party

Sambandsflokkurin = Union Party

Four local political parties seek independence from Denmark: the People's Party (Hin føroyski fólkaflokkurin), Republic (Tjóðveldi), Progress (Framsókn) and Centre Party (Miðflokkurin). These parties, while spanning the political left and right, make up 17 of the Løgting's 33 seats.[19] In addition to this is the Self-Government Party (Sjálvstýrisflokkurin) generally touts the idea of sovereignty, albeit with a more moderate fervor than the aforementioned parties.[20]

1946 referendum

On September 14, 1946, a referendum regarding independence was held. With a valid vote count of 11,146, 50.74% voted in favor of independence while 49.26% opted to remain associated with Denmark, leaving a difference of 166 votes between the two options.[21] The chairman of the Løgting declared independence on September 18; this move was not recognised by the opposition parties, and it was annulled by Denmark on September 20.[22] King Christian X of Denmark subsequently dissolved the Løgting; it was swiftly replaced in the parliamentary election held on November 8, with parties favoring union with Denmark now retaining a majority.[23]

Constitutional crisis

The Danish and Faroese governments have consistently haggled over the drastic revision of the Faroese constitution, with many clauses clashing with those of Denmark.[24] The conflict reached its apex in 2011, when then-Prime Minister of Denmark Lars Løkke Rasmussen declared that new edits could not coincide with the state's constitution. Rasmussen presented two options to the Faroese: secede or scrap the hypothetical constitution. Faroese Prime Minister Kaj Leo Johannesen asserted that they would begin a new draft of the constitution and remain in the Danish Realm.[25]

Concerns of economic viability

“It's currently only the money that actually connects us to Denmark. All Faroese agree that we should have our own schools and own language. The cultural battle is over. It’s the Danish money that is the obstacle to independence.”

—Høgni Hoydal, Faroese MP and leader of the Republic Party.[26]

Although they enjoy a significant amount of autonomy from Denmark, the Faroe Islands still regularly rely on USD $99.8 million of government subsidies to keep their economy stable;[24][failed verification] in 1992 a banking decline of 25% sent the economy into a period of stagnation and 15% of the population to mainland Denmark.[27] Financial support from the Danish government takes up 4.6% of the Faroese gross domestic product and accounts for 10-12% of the public budget.[26]

Norwegian oil and gas company Equinor has taken interest in the prospects of oil in the waters off of the Faroe Islands, embarking on an estimated US$166.46 million oil exploration operation.[27] Exxon Mobil and Atlantic Petroleum also hold stakes in the drilling platforms being installed in Faroese waters.[28] If these operations succeed and find the bountiful projected amounts of oil (USD $568,500 worth per each resident out of the Faroese population of 49,000) the prospect of independence may receive a boost.[27]

See also

- Constitution of Denmark

- Danish Realm

- Greenlandic independence

- Icelandic independence movement

- Norwegian independence movement

- List of active separatist movements in Europe

References

- ^ Adler-Nissen, Rebecca (2014). "The Faroe Islands: Independence dreams, globalist separatism and the Europeanization of postcolonial home rule" (PDF). Cooperation and Conflict. 49 (1): 55–79. doi:10.1177/0010836713514150. ISSN 0010-8367. JSTOR 45084243. S2CID 13718740.

- ^ Ackren, Maria (2006). "The Faroe Islands: Options for Independence". Islands Journal. 1.

- ^ Skaale, Sjúrður. (2004). The right to national self-determination : the Faroe Islands and Greenland. Nijhoff. ISBN 90-04-14207-X. OCLC 254447422.

- ^ "The Faroe Islands, Faroese History – A part of Randburg". Randburg.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-07.

- ^ "About the Faroe Islands". Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- ^ "The Peace Treaty of Kiel". 13 February 2007. kongehuset.no. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "The Faroese Parliament" (PDF). Logting. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Historical Timeline". Faroe Islands. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Historical overview" (PDF). Logting. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ 125 ár síðan jólafundin í 1888

- ^ Nú er tann stundin... Tjóðskaparrørsla og sjálvstýrispolitikkur til 1906

- ^ Føroyskar bókmentir, page 4 (in Faroese)

- ^ "Fólkakirkjan". Archived from the original on 2015-03-08. Retrieved 2014-04-21.

- ^ "Tjóðskapur". Archived from the original on 2014-04-22. Retrieved 2014-04-21.

- ^ "Faroe Islands and the British occupation". 24 July 2013. Sunvil Discovery. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "In Faroese". Logir.fo. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "The unity of the Realm". Stm.dk. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ Lov om de færøske myndigheders overtagelse af sager og sagsområder (written in Danish)

- ^ "FAROES/DK". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Government & Politics". Faroe Islands. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Faroe Islands, September 14, 1946: Status (In German)". 04 October 2013. Direct Democracy. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Faeroe (sic) Islands". World States Men. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "FAROES/DK". DemocracyWatch. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ a b Weinberg, Cory. "Iceland's Neighbours Turn Up Heat On Declaring Independence". 07 April 2012. Reykjavik Grapevine. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Alex. "Denmark and Faroe Islands in constitutional clash". 6 July 2011. Ice News. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ a b Topdahl, Rolv. "The Faroese nearer independence with oil". 20 August 2012. Aenergy. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Topdahl, Rolv. "Oil can turn the Faroe Islands into the new Kuwait". 23 August 2012. Aenergy. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ "Statoil to spud eighth Faroe well in two weeks". 1 June 2012. Aenergy. Retrieved 11 April 2014.