London in World War II

| London in World War II | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 September 1939 – 2 September 1945 | |||

Heinkel He 111 bomber over the Surrey Commercial Docks on 7 September 1940 | |||

| Location | London | ||

| Monarch(s) | George VI | ||

| Prime Minister(s) | Neville Chamberlain, Winston Churchill,

Clement Attlee | ||

| Key events | Kindertransport, evacuation, The Blitz | ||

Chronology

| |||

| History of London |

|---|

| See also |

|

|

The United Kingdom took part in World War II from 3 September 1939 until 15 August 1945. At the beginning of the war in 1939, London was the largest city in the world, with 8.2 million inhabitants.[1] It was the capital not just for the United Kingdom, but for the entire British Empire. London was central to the British war effort. It was the favourite target of the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) in 1940, and in 1944-45 the target of the V-1 cruise missile, the V-2 rocket, and the unsuccessful V-3 "London gun".

An estimated 18,688 civilians in London were killed during the war,[2] 0.23% of the population.[3] 1.5 million were made homeless.[4] 3.5 million homes and 9,000,000 square feet (840,000 m2) of office space were destroyed or damaged.[5]

Preparations

As early as June 1935, Air Raid Precautions (ARP) schemes were being put into place across London. The rules and resources of such schemes varied from borough to borough. ARP officers were expected to co-ordinate firefighting teams, rescuers and building repair in preparation for bombing raids.[6] In June 1938, the Women's Voluntary Service (WVS) was founded at 41 Tothill Street to help combat and protect against air raids.[7] At night, London was put under "black-out" rules, intended to make it as difficult as possible for the city to be seen from the air at night. Light sources such as street lamps, car headlights, and even cigarettes were to be put out or covered.[8] In September 1938, Londoners were asked to present themselves at a local assembly point to be issued with gas masks to protect against mustard gas attacks.[9]

London was encircled with three rings of defence. The outermost ring linked suburbs such as Rickmansworth, Potters Bar, Epping Forest, Hounslow, Kingston-upon-Thames and Bromley; the middle ring ran through Enfield, Harrow, Wanstead and West Norwood; and the inner ring ran around the north bank of the Thames from the river Brent to the river Lea. The outer two rings were anti-tank lines involving trenches, pillboxes and roadblocks; and the innermost ring was manned by the army.[10] Floodgates were installed on the London Underground system to prevent the river breaching the tunnels. Barrage balloons were floated above London's skyline, forcing bomber planes to fly at an altitude that made it difficult for them to aim accurately. Some boroughs ran exercises to train their citizens and civil defence in the event of air raids.[11] A flat in Fitzmaurice Place in Mayfair was acquired amidst great secrecy as a bolt-hole for the royal family in the event that London was invaded.[12] Plans were also drawn up for them to flee to Canada if necessary.[13]

In preparation for expected bombing raids, museums and libraries sent important materials to safety in the countryside. Beginning in August 1939, the collections of the Natural History Museum were evacuated to various stately homes around the countryside. The museum was open intermittently through the war.[14] Around 30,000 rare books and manuscripts were moved from the British Museum to the National Library of Wales, and later from there to a disused quarry in Wiltshire.[15] The National Gallery removed all its paintings from the premises to various locations, mostly in Wales.[16] Aldwych Station was used to store valuables from the British Museum and the Public Record Office, including the Parthenon Marbles.[17] Westminster Abbey's treasures were moved out of the church, and its immovable tombs protected with 60,000 sandbags.[18] All venomous animals in London Zoo were killed to prevent them harming the public should they escape, and some large animals such as pandas and elephants were transferred to other zoos.[19]

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) put down 400,000 pets in London in the first week of the war alone in order to save food.[20]

At noon on 1 September 1939, television producers at the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) headquarters in Alexandra Palace were told that the facility was shutting down immediately. The BBC announced that they would only be broadcasting radio on a single channel.[21]

Evacuation

On 28 September 1938, the London County Council (LCC) began to evacuate the first children from London to places in the country which were thought to be safer. The first contingent was made up of 1,200 nursery-school children and 3,100 physically disabled children. However, as a year passed without war materialising, plans to evacuate further children were cancelled.[22]

On 1 September 1939, two days before the outbreak of war, the evacuation programme was re-started in earnest.[23] Most of the evacuees left London by rail, although some along the riverside, particularly in Dagenham, left by boat, and more affluent families escorted their children in cars.[24]

Fewer than half of all London parents took advantage of the scheme.[25] When the children reached the countryside, their collection was sporadically organised, with some siblings being split up, and children paired with unsuitable guardians. There was no bombing in 1939, and most of the evacuees soon returned.[26] By mid-October, an estimated 50,000 mothers and children were back in London.[27] However, for those children who remained in or returned to London, schools were often closed and teachers evacuated with the rest of the class: by 11 January 1940, only 15 schools were open in the LCC area.[27]

It wasn't just children evacuated from London- London hospitals evacuated their patients, and the government evacuated thousands of civil servants under the codename "Plan Yellow".[28] Many civilians also moved out of London of their own accord at the beginning of the war, and by March 1940, the population of Chelsea had fallen from 57,000 to 36,000.[29]

Food and rationing

In the first few months of the war, prices of essential goods spiked, with price controls being introduced in November 1939.[30] Shopkeepers who were thought to be war profiteering by unduly raising their prices were liable to cause public outcry, or even to have their premises picketed by the Stepney Tenants' Defence League.[30] Rationing rules were introduced throughout the war, beginning with petrol in September 1939, and expanding to cover food and clothing.[31] When rumours spread about new rationing rules, some Londoners engaged in panic-buying before the restrictions were introduced- for example, writer Rose Macaulay witnessed "cars queueing up for miles round each garage to fill up" before petrol rationing was introduced.[32] With petrol hard to come by, London's roads became deserted, with even buses and taxis being taken out of service.[32]

Wealthy people could avoid the rules on rationing by eating at restaurants: for example, in May 1942, the war correspondent James Lansdale Hodson had smoked salmon, mushroom pâte, chicken, pudding, a cocktail and red wine at The Berkeley, writing "It's clear to me that if you have the brass [...] you can live in London very well." Later that month, restaurants were forbidden from charging more than five shillings for a meal in order to curb extravagance.[33] Many restaurants reduced the size and luxuriousness of their dishes. The American Brigadier-General Raymond E. Lee noted that in London "one gets only a lump of sugar and a thin little flake of butter. No more iced cakes. Fewer kinds of cheese. Only six pages in the newspaper. All paper is saved."[34] London County Council also opened "British Restaurants" in places such as Fishmongers' Hall, the Royal Veterinary College, and Gloucester House, which provided cheap, nourishing food in comfortable surroundings.[35]

As well as some foodstuffs being rationed, some were impossible to get altogether. In April 1940, Lord Woolton announced that bananas would not return to London's grocers until after the war.[36] One St. John's Wood resident, Rosemary Black, was left the following note by her maid: "Madam, there is no honey, no sultanas, currants or raisings, no mixed fruits, no saccarine at present, no spaghetti, no sage, no herrings, kippers or sprats (smoked or plain), no matches at present, no kindling wood, no fat or dripping, no tins of celery, tomato or salmon. I have bought three pounds of parsnips."[37] Spirits were difficult to come by and subject to price controls when they did appear. Some Londoners took to illegally distilling their own "hooch" instead, which could cause methyl poisoning.[38] Feeding pets with food fit for human consumption was banned by the government, to the effect that even dog food became hard to come by.[37] The public were encouraged to try new foods that were easier to get: the Naval and Military Club served catfish; horse was served in the House of Commons, and rook pie at the Grosvenor House Hotel.[38] Some Londoners took up gardening in order to increase their access to vegetables, and public parks were turned into allotments to facilitate this. It was estimated that the parks of Croydon alone produced 15,000 meals a day.[37] Tomatoes were grown in the window-boxes of Chatham House; the forecourt of the British Museum had peas, beans, onions and lettuces; and the roof of New Zealand House had three beehives. Many Londoners kept chickens or subscribed to pig clubs, and a flock of sheep were kept in Kensington Gardens.[39]

Some Londoners considered it a point of pride to strictly follow rationing, but others illegally bought rationed goods from the black market. One Italian restaurant in Jermyn Street served steaks concealed under a huge pile of spinach.[40] One civil servant called Mary Davies was served a black-market haggis by a friend, and wrote that "My sort of level wouldn't have done any black marketing [...] We would have considered that not really the done thing."[41] There was also a "grey market" involving giving rationed goods as gifts- for example, the Walworth reverend J. G. Markham was offered a box of prunes by one of his parishioners.[41] A common misconception among Londoners was that Jewish people were particularly strongly involved in or profiteering from the black market, but when the Royal Statistical Society studied the matter, they found that only three out of 50 convicted black marketeers were Jewish.[41]

Food wastage was severely frowned-upon. Some Londoners were prosecuted for feeding bread to birds at Hyde Park, and Vere Hodgson was reprimanded by Kensington Salvage Council for throwing away mouldy bread.[42] Wandsworth Council delivered cooking lessons on how to make cakes without fat or sugar, or make a family-sized bean cutlet for fourpence.[42]

Londoners were encouraged to save paper in large quantities. Newspapers reduced to four or six pages long.[43] In June 1943, Londoners donated their old books for salvage, recycling a grand total of 5.5 million books.[44]

Bombing

Prior to September 1939, it was widely-known in Britain that in the event of war in Europe, London would be the target of a bombing campaign. The Air Ministry predicted casualty rates of 18,750 per week in the capital,[45] and the Mental Health Emergency Committee predicted that 3-4 million people would develop mental health problems such as hysteria.[46] In Fulham, mass graves were dug in North Sheen Cemetery to accommodate the expected thousands of dead each night.[46]

At the beginning of the war, German dictator Adolf Hitler ordered that London was not to be attacked. However, on 24/25 August 1940, several bombs were dropped on London. Whether this was due to a change of heart on the part of Germany or due to an error on the part of the aircrew is debated, but British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered retaliatory attacks on Berlin in response.[47]

The heaviest-hit areas of London during the war were the City of London, Holborn, and Stepney, each receiving over 600 bombs per 1,000 acres (4.0 km2), followed by Bermondsey, Deptford, Southwark, and Westminster.[48]

The Blitz

On the first day of Britain declaring war, the air-raid sirens in London went off three times, each a false alarm.[49] Bombing of London began in earnest on 7 September 1940, regarded as the start of the bombing campaign known as the Blitz[50] and dubbed "Black Saturday".[51] On that night, 13 members of the Air Raid Precautions (ARP) and fire services were killed in a hit on Abbey Road Depot in West Ham,[51] and the Surrey Commercial Docks in Rotherhithe were set alight in the Surrey Docks Fire.[50] As over 1,000 firefighting crews arrived all through the night to fight the fire, telegraph poles and wooden roadblocks spontaneously burst into flame from the heat, and half a mile of shoreline was burned down, including 350,000 tons of timber stored in dock warehouses.[52] London was bombed for 57 consecutive nights from 7 September to 2 November.[50]

The authorities were concerned that Germany would use poison gas bombs, although this never materialised. Pillar boxes were painted with yellow squares which would change colour in the presence of gas. Londoners were issued with gas masks and exhorted to carry them at all times, although it was never made mandatory. Carrying a gas mask quickly became unfashionable- in September 1939, 71% of men and 76% of women on Westminster Bridge were carrying their masks. By November, it was just 24% and 39%.[53]

On 29/30 December 1940, the bombing was so heavy that the night was nicknamed the "Second Great Fire of London". Many firewatchers were off-duty over the Christmas period, and so the fires from incendiary bombs were able to spread quickly across rooftops.[54] The City of London was particularly badly hit, including the area around St. Paul's Cathedral, which Prime Minister Winston Churchill had declared should be protected at all costs.[55] A photograph called St. Paul's Survives was taken of the dome of the cathedral wreathed in smoke, which was dubbed "the war's greatest picture" and used both by British and German propaganda efforts to illustrate both the building standing tall and undamaged despite heavy attacks, and the building appearing weak and small and surrounded by German firepower.[56] Overall, 12 firemen and 162 civilians died during the night.[55] Buildings destroyed or damaged on this night include Trinity House and the churches of All-Hallows-By-The-Tower, Christchurch Greyfriars, and St. Lawrence Jewry.[57]

The last major raid took place on 10/11 May 1941. It killed 1,436 civilians, more than any other raid on Britain during the war, and hitting buildings from Hammersmith in the west to Romford in the east, including the House of Commons, Westminster Abbey, the Royal Mint and the Tower of London.[45] This date is considered the end of the Blitz proper, although raids do continue more sporadically after this, including one on 27/28 July 1941.[58] Throughout the Blitz, 20,000 tons of bombs were dropped on London, killing 20,000 and injuring another 25,000.[59]

V-1 and V-2 attacks

On 13 June 1944, London was hit by the first of many Vergeltungswaffe-Eins (Revenge Weapon 1), or V-1 rockets, nicknamed "doodlebugs" or "buzz bombs" by Londoners. The V-1 was a bomb that required no crew, and was fired from launch sites initially in northern France. They could not target specific buildings, but could be fired towards London at an average speed of 350 mph (560 km/h).[60] The first one to hit London landed on Grove Road on 13 June 1944, killing six people.[61] Over 900 landed in London between 13 June and 1 September 1944- on average, one every two hours for 81 consecutive days.[62] Once they reached their target, the engine would cut out, meaning that Londoners who heard the noise of them flying overhead knew that they were safe, but if they heard the noise stop, they would have about twelve seconds to find cover before the bomb reached its target.[63]

When Allied forces captured the French V-1 launch sites in September 1944, the number of V-1 attacks fell. Instead, the German air force Luftwaffe were forced to launch them from aircraft, making them much less frequent until they stopped entirely in January 1945.[62]

On 8 September 1944, Staveley Road in Chiswick was hit with the first V-2 rocket attack.[64] These could be launched from Holland, could not be heard approaching, could not be tracked by radar, and could not be brought down by anti-aircraft guns or fighter planes. The highest death toll from a single V-2 attack was on 25 November 1944, when a Woolworth's shop in Deptford was it, killing 160 people.[65]

Through the Double-Cross System the Germans were misled to think that those aimed at London were falling short, so moving attacks on London away from the more densely populated centre of London.

In total, an estimated 963 V-1 and 164 V-2 rockets landed on London during the war.[66]

Air-raid shelters

The British government knew well before entering the conflict, that should war break out, bomb shelters would be required. However, they feared the public developing a "deep shelter mentality", refusing to leave the safety of underground bunkers, and so at the beginning of the war were reluctant to provide well-fortified underground shelters for public use.[67] Early public shelters were poorly-built trenches dug in public parks made of wood and corrugated steel, or brick and concrete, which were often waterlogged and could not stand up to a bomb falling nearby.[3] On 15 October 1940, a bomb hit the trench system in Kennington Park, and the those inside were so thoroughly blown up that only 48 bodies were recovered from what was thought to be over 100 people taking shelter in the trench. Eventually, the clean-up team gave up and simply filled the trench with lime and covered it over.[68]

Where possible, civilians were expected to take shelter either in reinforced rooms in their own homes, or in prefabricated Anderson shelters given for free by the council in their back gardens. However, many Londoners, especially inhabitants of poorer districts such as the East End, had no gardens, and did not live in a house sturdy enough to provide any protection.[62] For these Londoners, and for people away from their homes during an air raid, public shelters were opened in the crypts of churches such as St. Martin-in-the-Fields, in basements of housing blocks, office buildings and shops, or under railway arches.[69]

A small fraction of Londoners chose to use London Underground stations for shelter.[3] This practice was officially banned by the government from the beginning of the war until September 1940, as they feared that large numbers of shelterers would impede the train service.[70] This policy reversed during the war. At Borough station, a disused tunnel was converted into a shelter for up to 14,000 people.[71] New deep-level shelters were also constructed at Clapham South, Clapham Common, Clapham North, Stockwell, Chancery Lane, Goodge Street, Camden Town and Belsize Park stations, with toilets, washing facilities, and bunks to sleep in.[72] Some underground shelters even hosted concerts put on by the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA).[17] Although images of Londoners sheltering in Tube stations are well-known, the number of Londoners using the Underground in this way peaked in September 1940, with an estimated 177,000 people- a tiny percentage of all Londoners.[70] Using the Underground did not guarantee safety: 19 people were killed taking shelter in Bounds Green station on 13 October 1940, and 64 were killed at Balham station on 14 October 1940.[73] In January 1941, a bomb landed on Bank junction with such force that it completely exposed the Bank Station ticketing hall underneath, killing 58 people.[74] The worst civilian disaster in Britain in World War II took place at Bethnal Green Underground shelter on 3 March 1943, when a panicked crush took place on the stairs as people tried to enter the shelter. Over 170 people died, despite no bombs falling in the area.[75]

Still others did not seek to take any shelter at all, but remained in their beds.[71] Unlike in Germany, in Britain it was not compulsory to seek shelter during an air raid.[3] In November 1940, a London taxi driver told Vera Brittain that he continued to sleep on the top floor of his block of flats every night through the bombings, saying, "Unless it has me name on it, it won't git me."[3] A survey carried out by government scientist Solly Zuckerman found that 51% of urban families did not take shelter.[3]

Building damage

The John Lewis department store on Oxford Street was severely damaged in raids on 18 September 1940, and was replaced with a new building in September 1960.[76]

On 14 October 1940, the church of St. James' Piccadilly was badly damaged, and was rededicated by the Bishop of London in 1954. A plaque outside the church commemorates the event.[77]

The Twinings tea shop, which had been on the Strand since 1706, was destroyed on 11 January 1941 and rebuilt in 1952.[78]

The British Museum was hit several times during the war, with the worst incident being in May 1941, when 240,000 books in the museum library were damaged or destroyed by fire and water damage. Also hit was a satellite collection in Colindale, which destroyed 6,000 volumes of English and Irish newspapers.[15]

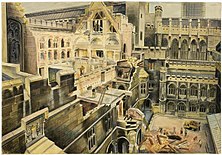

The Palace of Westminster also suffered several hits during the war, with the most serious being on 10/11 May 1941. An incendiary bomb came through the roof, and firefighters had to decide whether to save the House of Commons chamber or the ancient Westminster Hall. They concentrated on the hall. While no-one was hurt, the chamber was unusable, and so for the rest of the war the House of Commons met in other locations such as the House of Lords Chamber, the Robing Room, or Church House near Westminster Abbey. The House of Commons was repaired in 1950.[79] The Abbey itself was also hit that night, with the bulk of the damage done to its surrounding buildings such as the Deanery and Westminster School Hall.[80]

Buckingham Palace was struck at least nine times during the war, with the most damage being caused on 13 September 1940. Winston Churchill and the Queen were inside at the time and saw two of the bombs falling outside their window. One of the bombs destroyed the palace's chapel, which was rebuilt as the Queen's Gallery. The heaviest-hit areas of London often tended to be where working-class people lived, as they were next to militarily useful targets like docks and factories, and in the aftermath of the Buckingham Palace bombing, the Queen said, "Now I can look the East End in the face."[81]

Buildings in London still bearing shrapnel marks include the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Tate Britain gallery, St. Clement Danes church, the Ritz Hotel, and Holy Trinity Church in Clapham.[82] The churches of Christchurch Greyfriars and St. Dunstan-in-the-East have been left in ruins and turned into public gardens.[83] The ruins of the church of St. Mary Aldermanbury stood in place for many years after the end of the war, until being dismantled stone-by-stone and shipped to Fulton, Missouri, where the church was rebuilt. Today a garden stands on the spot in London where only the church's foundations remain.[84]

Wartime leadership

Many British wartime leaders were based in London for part of or the whole duration of the war, including Prime Ministers Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill. As early as 1936, then-backbench Member of Parliament Churchill called for the creation of a "War Room" from which the government could direct a war in the event of London's bombing or destruction.[85] On 24 March 1938, plans to construct a purpose-built bunker underneath the New Public Offices (now the Treasury building) on Great George Street were approved, and construction began on what is now known as the Churchill War Rooms.[86] They were first used on 23 August 1939, when German leader Adolf Hitler signed a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, and the lights would not be turned off for another six years.[87] In May 1940, days after Churchill was made Prime Minister, he visited the bunker and said, "This is the room from which I'll direct the war."[88] The complex contained a Cabinet Room where government figures could meet with the armed forces Chiefs of Staff; a Map Room where fronts and ship convoys across the whole war could be mapped out, 24 hours a day; equipment for broadcasting Churchill's speeches on the radio or for contacting American president Franklin D. Roosevelt; bedrooms for Churchill and other high-ranking figures; and offices and sleeping quarters for dozens of typists, stenographers, switchboard operators and secretaries.[89] On 14 August 1945, word reached the complex that Japan had surrendered, and the next day, the officers cleared out their belongings and vacated the premises.[90] The rooms have since been preserved as a museum and opened to the public.[89] The War Cabinet also met at the closed-down Down Street Underground station, which was fitting out with meeting rooms and a bed and bathtub for Churchill's use. After the Cabinet War Rooms were completed, the War Cabinet vacated the station, which became the control centre for the country's rail network and the headquarters of the Railway Executive Committee, with a staff of 75 people.[91]

The Secretary of State for War and the Chief of the Imperial General Staff had their headquarters in the Old War Office on Whitehall. During the war, it expanded rapidly to the surrounding buildings, occupying space in the Victoria Hotel and Metropole Hotel, among others.[92]

The Royal Navy was run by a body known as the Admiralty, who operated from the Admiralty Building on Whitehall. Upon the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939, Winston Churchill was appointed the First Lord of the Admiralty. The fleet comprised over 500 ships, including 7 aircraft carriers, 184 destroyers, and 58 submarines. The Admiralty's tasks included safeguarding the merchant navy, defusing German sea mines, and extracting over 300,000 troops from Dunkirk in Operation Dynamo. Linked to the Admiralty Building is Admiralty House, which was occupied by Winston Churchill during the war.[93]

The Ministry of Information, the British government's propaganda wing, was based in Senate House in Bloomsbury during the war. The University of London Library continued to function in the building, primarily to serve the Ministry.[94]

London also saw the early days of the United Nations (UN) during the war. On 12 June 1941, exiled European governments and representatives from the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries signed the "Declaration of St. James's Palace", seen as one of the founding documents of the UN, in which they declared their intention to work for "the willing cooperation of free peoples in a world which, relieved of the menace of aggression, all may enjoy economic and social security".[95]

Military Intelligence

Upon the outbreak of war, the Security Service, commonly known as MI5, moved their headquarters to the Wormwood Scrubs prison in East Acton in order to gain more office space. In July 1939, just before the war, the service only had three officers, whereas by January 1940 it had 102. Staff converted cells into offices. In October 1940, the bulk of the service was moved out of the prison to more luxurious accommodation in Blenheim Palace.[96] MI5 kept a London office at 57-58 St. James's Street, where they ran a double-cross spy ring. Here, captured members of the German secret service, the Abwehr, were turned to work for the British as double agents, either remaining in Britain or travelling back to Germany with false information. The double agents, particularly codenames Tricycle, Bronx, Brutus, Garbo and Treasure, conducted Operation Fortitude, successfully convincing German high command that the Allies would target Calais rather than Normandy on D-Day.[97] MI5 also planned Operation Mincemeat from London, a scheme to make Germany think that the Allies were not planning to invade the island of Sicily. The body of a deceased man from St. Pancras called Glyndwr Michael was given false papers indicating that he was an officer, and false outlines of the Allies' intentions, and allowed to wash up on the coast of Spain, to be found by German forces.[98]

The Secret Intelligence Service, commonly known as MI6, was based at 54 Broadway during the war. Their job was to gain tactical information on hostile nations, particularly Germany. They ran a code-breaking ring from Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, where staff broke the Enigma ciphers that were used to encode radio traffic sent from the Luftwaffe, Abwehr, German army, and German navy.[99]

MI9, led by Brigadier Norman Crockatt, was formed to help Allied soldiers escape from occupied Europe. Returning servicemen were often sent to the Grand Central Hotel (now the Landmark London) in Marylebone for questioning.[100] Numbers 6 to 8 on Kensington Palace Gardens became the Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre (CSDIC), known as The Cage, and used by MI9 for prisoner interrogation.[101] Over 3,500 prisoners are thought to have passed through the London Cage, with reports of sleep deprivation, reduced rations and casual beatings being common. Some prisoners also reported being made to walk in a small circle for hours, continuous physical exercise, and ice-cold water dousings. These allegations were corroborated by the memoirs of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Scotland, who ran the establishment 1940-1948.[102]

Special Operations Executive

The mission of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) was to train and direct saboteur agents in enemy territory such as occupied France, Czechoslovakia, Norway, and Belgium- in the words of Winston Churchill, to "set Europe ablaze".[103] They used several buildings around London for their operations, including their headquarters at 64 Baker Street[104] and recruited Londoners including Violette Szabo,[105] Noor Inayat Khan[106] and F. F. E. Yeo-Thomas[107] as field agents. Their Camouflage Section was responsible for concealing film, radios and other equipment inside innocuous objects like coal, dead rats, or a tube of toothpaste, and started working from 56 Queen's Gate, before moving to the Victoria and Albert Museum and then the Thatched Barn near Elstree over the course of the war. Numbers 2 and 3 Trevor Square, were used by the SOE for their Make-Up Section, helping agents change their appearance, and their Photographic Section, creating photos to use on false identity documents.[108] The Signals Directorate, responsible for codes and communicating with agents, was based in Montagu Mansions off Baker Street.[109]

The French section of the SOE used a flat in Orchard Court in Portman Square to brief new agents rather than the headquarters, to reduce the possibility of them seeing classified information or giving away the position of the main hub. The flat was rather small for the purpose, and new recruits were sometimes made to wait in the bathroom.[110]

Changes to buildings and public spaces

Many buildings and public spaces in London underwent a change of usage before or during the conflict, as society and the economy adapted to the needs of the war effort. For example, Selfridges department store on Oxford Street continued to trade during the war, but the basement hosted American-made X-system encryption machines, code-named SIGSALY. This system allowed Prime Minister Winston Churchill and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to communicate on a secure telephone line across the Atlantic Ocean.[111] Grosvenor Square became the station for a barrage balloon nicknamed "Romeo" flown by the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), who were housed nearby in Nissen huts.[112] King George VI had part of the Buckingham Palace gardens converted into a firing range so that he and other members of the royal family could practice their marksmanship for use in a possible invasion.[81] Many London parks, including Regent's Park and Hyde Park, had anti-aircraft batteries stationed in them. Regent's Park was also used as a place to safely detonate dropped bombs that had not exploded.[98] Londoners were called upon to grow their own food, and many public areas were turned into allotments, including the Tower of London moat,[113] Kensington Palace gardens, and Hampstead Heath.[114]

Adjoining the Admiralty Building on Whitehall, a large "citadel" was constructed, although it wasn't completed until the main period of the Blitz was over. Its purpose was to allow naval intelligence officers to continue to work safely through bombing raids, and as a last line of defence to retreat to in the event of an invasion by paratroopers.[115]

Many areas in London such as Bloomsbury and Belgravia feature wrought-iron railings around houses and gardens such as Russell Square, Bedford Square and Bloomsbury Square.[116] In the early part of the war, metal railing fences of such areas were melted down and manufactured into aeroplanes, tanks and ammunition to serve the war effort.[117] Towards the end of the war, the question arose of whether to replace them. Bloomsbury in particular housed many poorer Londoners who lived near to many garden squares, but were barred from accessing them by the railings. In the newspaper Tribune, author and journalist George Orwell called the removal "a democratic gesture", saying, "more green spaces were now open to the public, and you could stay in the parks till all hours instead of being hounded out at closing times by grim-faced keepers."[118]

The National Gallery had been empty of paintings since the beginning of the war, with most of the collection dispersed in museums around Wales or, from the summer of 1941, a disused slate mine near Blaenau Ffestiniog.[16] Instead, the director of the gallery, Kenneth Clark, invited the pianist Myra Hess to give a concert in the empty building. It drew large crowds and became a series of lunchtime concerts. The Gallery also began showing temporary exhibitions, and from 1942, one painting was brought back from the slate mine each month, beginning the Picture of the Month scheme which still runs at the gallery to this day.[16]

Arrivals from overseas

Many Germans and Austrians in London were arrested in September 1939 and sent to either Olympia in West Kensington or the Royal Victoria Patriotic Asylum on Wandsworth Common before being moved out of the city, with true Nazi sympathisers like Baron von Pillar kept together with German-Jewish refugees like Eugen Spier. The Austrian-British psychoanalyst Anna Freud had her wireless set confiscated, and advertisements for domestic staff sometimes read, "No Germans need apply".[119] There was another wave of arrests in May 1940, with 3,500 Londoners being arrested within two weeks, some for the second time.[120] Those thought to be a lesser threat were not arrested, but instead given midnight curfews.[120] In June 1940, Italy joined the war and many Italian Londoners were arrested, including waiters at the Ritz, Carlton, and Berkeley hotels. Italian restaurants in Soho put up signs in their window saying "100 per cent patriotic British", but still had their windows smashed.[121] After Japan joined the war, twenty Japanese diplomats were put up in flats in Kensington until they could be safely returned to Tokyo, with a guard of eight policemen to accompany them when they left the building.[122]

Soldiers from many countries were stationed in London, giving it a more cosmopolitan air than it had previously experienced. Polish, French and Czech soldiers in particular became a more common sight in the city.[123] The Colonial Office financed a mosque in East London to accommodate Muslim soldiers arriving from various parts of the British Empire.[124] Members of the Free French Forces were catered to be Le Petit Club in St. James's Place, run by Olwen Vaughan.[125]

On 10 May 1941, Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess flew his private plane to Scotland. Upon arrival, he was captured and briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London before being transferred to Mytchett Place near Aldershot for the rest of the war.[126]

Refugees

In the run-up to the war, between 1933 and 1939, 29,000 German refugees were admitted to Britain, most of whom took up residence in London.[127] Although some felt welcomed, some Londoners viewed them with suspicion and many were interned for some part of the war. On 16 February 1939, the London newspaper Evening Standard ran the headline, "Hitler's Gestapo Employing Jews For Spying In England".[127] The Nigerian ARP warden E. I. Expenyon found that Londoners were happy to take orders from him- "wherever my duties take me, the people listen to my instructions"- but he was forced to defend a group of European refugees who were being abused in one of his shelters.[128]

Between 1938 and 1939, 9,354 German, Austrian and Czech children, mainly Jewish, were sent away by their parents to countries such as Britain, Holland, Sweden and Canada to escape Nazi persecution. The program was known as the Kindertransport. The British effort was organised chiefly by the Central British Fund for Germany Jewry (CBF). The children were allowed to pack a small suitcase. Children arriving in Britain generally came on a train from Harwich to Liverpool Street Station in London, where foster families arrived to collect them. Those without foster families were sent to a refugee camp. During the war, as fears of invasion rose, they were classified as Enemy Aliens and many were interned on the Isle of Man. After the war, many wrote letters to the Red Cross to find out what had happened to their parents.[129] There are two statues dedicated to the Kindertransport in Liverpool Street Station.

Many European royals whose countries were occupied by Axis powers fled to London for the duration of the war, including those of Norway, the Netherlands, and Poland. King Haakon VII of Norway led a government-in-exile from Kensington, and Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands lived in Belgravia.[130] Prince Peter of Yugoslavia and Princess Alexandra of Greece both fled to Britain separately, and were married in the Yugoslavian Embassy (now the embassies of Serbia and Montenegro in Belgrave Square) in London on 20 March 1944, with King George VI as best man.[131] The next year, Alexandra gave birth to Crown Prince Alexander Karadjordjevic in Suite 212 of Claridge's Hotel on Brook Street, which Winston Churcill declared to be Yugoslavian territory for 24 hours so that the baby could be born on Yugoslavian soil.[132] European governments also moved to London: the Belgian Cabinet formed a government-in-exile from 103 Belgrave Place,[133] and the Polish government were based in 47 Portland Place.[134] The French commander Charles de Gaulle lived at the Connaught Hotel,[135] and commanded the Free French Forces from 4 Carlton Terrace in St. James's after the French government surrendered to Germany.[136] De Gaulle escaped from occupied France on 16 June 1940, and two days later, made a BBC radio broadcast calling on French citizens to resist German occupation.[137]

Americans in London

Even before the US joining the war, American presence in London was notable, with over 2000 Americans working at the embassy in Grosvenor Square. Six months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor which signalled the US's entry into the war, that number doubled.[138] By June 1944, US troops in London had 33 officers' billets, 300 buildings for soldiers' accommodation, and 2,500,000 square feet (230,000 m2) of floor space for offices, gyms, and other uses.[123] The American general Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander-in-chief of the Allied forces, was based in London for much of the war, and used offices in Grosvenor Square, St. James's Square, and a deep-level shelter in Goodge Street underground station.[139] So many high-ranking American officers and staff were based in Grosvenor Square that it was nicknamed "Little America".[112]

The Savoy Hotel was a particular favourite among American journalists: novelist Mollie Panter-Downes writes that in the hotel bar the day after Pearl Harbor, there was much "slapping backs and singing 'Oh say, can you see?'".[138] On Piccadilly, an American Red Cross service club called "Rainbow Corner" opened to cater to American GIs, serving them things that were otherwise hard to get in Britain, such as doughnuts.[140] It could seat 2,000 people, and when it was first opened in November 1942, the key was thrown away to symbolise that the club would be open 24 hours a day.[123] With their smart uniforms, access to rationed goods like sweets and cigarettes, and Hollywood accents, British women often found American soldiers particularly exciting and attractive.[141] Writer Evelyn Waugh notes that American soldiers "passionately and publicly embraced" British women, who were "rewarded with chewing-gum, razor-blades and other rare trade goods."[142] Piccadilly Circus became the centre of a booming sex trade that catered particularly to Americans.[142] However, Wimbledon resident Pamela Winfield notes that "in fact we found out that the majority were small-town boys, straight out of high school, and church-going".[141] GIs also used Piccadilly Circus to find other men, with the serviceman Bill Wynkoop saying that he saw a "large number of servicemen of all nations and ranks cruising each other in Piccadilly and Leicester Square. Here were thousands of female [sex workers] wandering around, but these men were choosing each other".[143]

However, some Londoners were suspicious of American arrivals: rumours circulated of British people accidentally bumping into Americans in the blackout and being knocked unconscious; and tales of sexual assault were also common.[144] Resentment stemmed partly from the fact that American soldiers were much better paid, and often better fed, than their British counterparts, allowing them to live more luxurious lifestyles. A common complaint was that Americans were "over-paid, over-sexed, and over here."[145]

One particular point of contention was how to deal with both black soldiers from the United States and the British Empire arriving in London, and white officers from the south of the US who expected racial segregation in public life. Ministerial secretary Oliver Harvey wrote, "If we treat them naturally as equals, there will be trouble with the Southern officers." Although American-style segregation was never made official policy in Britain, the British authorities were shy of offending American segregationists, and Major-General Arthur Dowler issued a note advising white women not to go out with black soldiers, and to copy how white Americans treated their black comrades.[146] The West Indian cricketer Learie Constantine was asked to leave the Imperial Hotel after American guests complained about his presence. The hotel was fined £5.50, with the judge writing how sorry he was that, because of a legal technicality, he could not raise the amount.[147]

Women in "men's roles"

Women were allowed to join all three auxiliary branches of the armed forces (Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), Women's Royal Naval Service (WRENS), and Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF)) from the beginning of the war, although the kinds of work they were allowed to do was heavily restricted. At the beginning of the war, the Home Guard only accepted women in auxiliary roles.[148]

The Home Guard (initially Local Defence Volunteers or LDV) was an armed citizen militia supporting the British Army during the Second World War, which at first did not allow women to join. The MP for Fulham West, Dr. Edith Summerskill, argued for women to be allowed to join on equal terms to men, saying that "I am not asking for women to be included solely as cooks and clerks in the Home Guard but in the same capacity as men, with equal rights and privileges". She herself openly flouted the ban on women by joining the Parliamentary Home Guard. In the summer of 1940, Venetia Foster formed the Amazon Defence Corps in London's West End, training women to use firearms to prove that they should be allowed to join. In March 1942, Summerskill estimated that 10,000 London women had joined an unofficial group called the Women's Home Defence Corps. The London Home Guard commander Douglas Brownrigg argued that he should be allowed to accept women "in non-combantant duties" in September 1941, and London women such as secretary Joan Hardy were joining well before the ban was lifted. Finally, on 20 April 1943, the first women were allowed to officially join the Home Guard, albeit in small numbers, in unarmed roles only, and without a uniform.[149]

Women were greatly needed in many spheres of work to replace male workers who had been called up to the armed forces, such as factory workers, bus conductors, bank tellers, fire engine drivers. In all these employments they were initially resisted by management, thought of as "temporaries" who could be let go as soon as the men came back, and only gradually accepted.[150] By the end of the war, women were working in the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI), the Land Army, the Timber Corps, the Royal Observer Corps, the police, fire and ambulance services, Air Raid Precautions, the Women's Voluntary Service, the Air Transport Auxiliary, the Junior Air Corps, the Girls Training Corps, and the River Emergency Service.[151]

In 1941, Britain became the first country to conscript women, into both the auxiliary armed forces and into jobs in industry.[152] As the war went on, it became necessary to recruit not only single women, but also women with families. Women demanded the establishment of more nurseries so that they could do essential war work. By the end of the war, over 75% of married women in London were doing war work of some kind.[153]

Crime

Certain kinds of crime became more common in London as people took advantage of empty or bombed-out houses and shops to steal valuables.[8] Fears arose of criminals using the extra cover of darkness provided by blackout rules to increase their activity. However, these fears were not borne out by statistics: the Metropolitan Police reported that crime in the first month of the blackout, September 1939, was 27% lower than the previous September. A senior police officer said "While there has been a slump in general crime, there has been an increase in certain classes of crime, such as bag-snatching, thefts of bicycles, thefts from standing cars and telephone boxes."[154]

Throughout the war, an increasing number of Londoners were drafted into service, either in the armed forces or in a job on the Home Front that supported the war effort. Those who voiced moral objections to taking part had to apply to their borough for an exemption to the draft, and on average, only about 4% of Londoners who applied for this exemption were granted it. Even those who were unsuccessful faced widespread condemnation as cowards, shirkers and "conchies"- short for "conscientious objector". Bermondsey Council fired all their conscientious objector employees, some of whom thereby lost their pensions, and some, such as Sidney Greaves, were imprisoned in Wormwood Scrubs.[155]

London's first bomb of the war was not German but from the IRA, who set off a device on 2 March 1940 outside the Whiteleys shop in Bayswater. Four days later, another exploded outside the Grosvenor House Hotel. No-one was killed in either blast.[155]

In March 1940, former governor of the Punjab, Michael O'Dwyer, was assassinated by Indian revolutionary Udham Singh at Caxton Hall in Westminster. The murder was an act of revenge for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, which took place in 1919 when O'Dwyer was governor of the region.[156] Singh was held in Brixton Prison, tried at the Central Criminal Court, and executed at Pentonville Prison.

In 1940, Parliament passed the Treachery Act, making it easier to prosecute people of wartime treason. 1,600 British citizens were arrested as soon as the law came into effect, including British fascist Oswald Mosley, who was confined in Holloway Prison for the duration of the war.[120] Several of those convicted under this Act were confined and executed in Wandsworth Prison. On 10 July 1941, George Johnson Armstrong was hanged at the prison after sending a letter to the German Consul in the United States offering to spy for Germany. On 3 November 1942, merchant seaman Duncan Scott-Ford was also hanged there after passing convoy route information to the Germans.[157]

In February 1942, the "Blackout Ripper" Gordon Cummins was accused of murdering Evelyn Oatley, Margaret Lowe, Doris Jouannet, and Evelyn Hamilton, and attempting to strangle Greta Heywood, around the West End across a six-day period. While attacking Greta, he was disturbed by a delivery boy and fled, leaving behind his RAF bag. He was tried at the Old Bailey, where the jury found him guilty of Oatley's murder after just 35 minutes. He was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 25 June 1943.[154]

Morale and "Blitz Spirit"

A popular image of the London Blitz holds that all Londoners pulled together, with high morale in the face of bombing.[158] This was certainly an image that the authorities wanted to portray, with the Ministry of Information putting out a film in 1940 titled London Can Take It!, describing how Londoners had "no fear and no panic".[159] To some extent, this does hold true. Londoners put up signs with defiant slogans on their bombed-out homes and businesses, such as "More open than usual", or "Close shaves a speciality" on a barbershop.[160] Some Londoners did display humour or an unflappable coolness during the Blitz. For example, John Hope recounts overhearing a Cockney woman on the train saying to another, "The 'ouse next door 'ad a terrible pasting. I found poor Mrs Andrews 'alf one side of 'er door and 'alf the other. Well, you 'ad to laugh!"[160] After witnessing the Bank underground bombing in 1941 which killed 111 people, the Hungarian doctor Z. A. Leitner said, "You English people cannot appreciate the discipline of your own people. I want to tell you, I have not found one hysterical, shouting patient... If Hitler could have been there for five minutes with me, he would have finished the war. He would have realised that he has got to take every Englishman and twist him by the neck- otherwise he cannot win this war."[161] Despite mental health facilities preparing for record numbers of cases, in fact, reports of mental illness west down during the war, including suicide.[161]

However, it was impossible for the war not to have some impact on Londoners. Sleep deprivation rose, with half of all Shoreditch residents getting less than four hours' sleep a night in September 1940.[162] Diarist Viola Bawtree and ambulance driver Nancy Bosanquet both report auditory hallucinations, hearing air-raid sirens when there were none.[163] By April 1941, American journalist Vincent Sheean reported that "You won't find any of the high-spirited we-can-take-it stuff of last year."[164]

Some Londoners turned on their Jewish neighbours, who lived particularly in the East End, around Spitalfields and Shoreditch. Anti-Semitic rumours inconsistently claimed that both Jewish people fled to the country at the first sign of trouble, and that they monopolised space in shelters; that they profited from the black market and refused to volunteer as ARP wardens or AFS officers. The Home Office kept watch on anti-Semitism in London by commissioning studies, one of which read that "though many Jewish people regularly congregate and sleep in the public shelters, so also do many of the Gentiles, nor is there any evidence to show that one or other predominates among those who have evacuated themselves voluntarily".[165]

Some working-class Londoners resented the fact that their homes bore the brunt of bombing- their districts, such as the East End, Bermondsey and Southwark, contained more strategically important targets such as factories and docks, their flimsily-built houses were less able to stand up to bomb damage, and they were less likely to have a country home to escape to. A bus driver told typist Hilda Neal that the authorities had allowed the Germans to freely bomb the East End, but "when the West End was touched the Government started the barrage".[166] On 15 September 1940, around 100 protestors, led by MP Phil Piratin, demanded shelter in the high-class Savoy Hotel. They were allowed in, but asked to leave 15 minutes later when the all-clear sounded.[167]

War artists

The War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC) was an official government body run by the Ministry of Information with the task of employing artists to record the war, many of whom were based in, or recorded, London.

William Roberts was commissioned to produce drawings of Corps Commanders in France, but abandoned his post. The War Office sent him to London in disgrace, where he drew workmen at the Woolwich Arsenal.[168] Roland Vivian Pitchforth captured Air-Raid Precautions in London in pictures such as AFS Practice with a Trailer-Pump on the banks of the Serpentine and Anti-Aircraft Guns Under Construction.[169] Leonard Rosoman worked as a fireman during the war, and produced the painting A House Collapsing on Two Firemen, Shoe Lane, of two of his colleagues immediately before they were both killed by a falling building, which was later purchased by the WAAC.[170] Graham Sutherland spent six months in the City and the East End recording bomb damage, including sleeping in a deckchair in the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral.[171] Henry Moore surreptitiously captured sleepers in London Underground Stations on a small sketchpad, saying, "They were undressing, after all [...] I would have been chased our if I'd been caught sketching."[172] Other war artists based in London included John Piper, Feliks Topolski, Ruskin Spear, and Walter Bayes.

Artists also had to dodge the Blitz themselves: several war artists such as Edward Ardizzone had their studios or homes destroyed, and Frank Dobson's bust of a commander was left looking like a "deflated football" after the Admiralty building where he was working on it was hit.[173]

Official war artists were strictly circumscribed in their choice of subject matter. Some artists, such as James Boswell and Clive Branson, were excluded altogether due to their links to the Communist Party.[174] Pictures of rioting, looting, anti-Semitism, panic, or gory scenes were deemed unacceptable. The artist Carel Weight had a picture rejected showing Wimbledon trolley-bus passengers fleeing for cover beneath a looming German plane. However, the WAAC did encourage artists to depict burned-out and bombed buildings before salvage crews had the chance to clean them up. For example, after the Second Great Fire of London, Muirhead Bone rushed down from the west coast of Scotland in order to produce a drawing of St. Bride's and the City after the Fire.[175] Otherwise, the WAAC were generally happy to leave artists to choose their own subjects, with the WAAC secretary, E. M. O'R. Dickey, saying, "Our plan has been to leave it more or less to the artists to produce what they think is fair."[176] This did mean that some subjects went unrepresented: for example, the Prime Minister Winston Churchill didn't appear in any official WAAC pictures made during the war, and pictures involving the royal family were rare.[177]

As well as traditional painters and sketchers, the Ministry of Information also commissioned photographers such as Bill Brandt, who recorded Londoners taking shelter in Tube stations, church crypts, and railway arches, and documented historic buildings that might be destroyed.[178]

Aftermath

On VE Day, the royal family and Prime Minister Winston Churchill appeared on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to cheering crowds.[81]

Although families were generally expected to bury their own dead during the war, in cases where this was not possible (due to a victim being unidentifiable or unclaimed, for example), they were buried by the local London borough. Most London boroughs had mass graves for this purpose, and most erected a memorial on the site after the war.[179] For example, Hampstead erected a memorial in Hampstead Cemetery, and Woolwich in Plumstead Cemetery.[180]

The war increased the depopulation of London's inner boroughs as people were forced to move out of their neighbourhoods due to bomb damage, and in some cases, did not return. For example, the population of Stepney dropped by over 40% during the war.[4] Calls grew for councils in affluent areas such as Paddington, Kensington and Chelsea to take over abandoned houses and let them to the homeless, particularly returning servicemen. A group of activists from Brighton took matters into their own hands, moving homeless people into empty houses. The idea spread throughout London. In July 1945, the activist John Prean moved a Mrs. Wareham and her seven children into a large house in Fernhead Road in Maida Vale, and vowed to continue his work until the council took it up. The new Labour government gave councils more powers to requisition abandoned properties, and the movement abated.[181]

Following the war, large numbers of leftover emergency stretchers used by the Civil Defence Service were recycled as replacement fences for many council estates in London. Some of these "stretcher railings" can still be seen today, for example on Atkins Road.[182] The stretchers are simply made: two steel poles with easily cleaned wire mesh between them, with a kinked "foot" at each end of the poles so the stretcher could be rested on the ground and picked up easily.[183] Many memorials to the war, those that worked for it, and those that were killed during it, have been erected in London since.[184]

See also

References

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 4.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 154.

- ^ a b c d e f Overy, Richard (16 March 2020). "The dangers of the Blitz spirit". HistoryExtra. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ a b Roy 1994, p. 342.

- ^ Roy 1994, p. 341-342.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Malcolmson, Patricia (2014). Women at the ready : the remarkable story of the Women's Voluntary Services on the Home Front. London: Abacus. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-349-13872-5.

- ^ a b BNA (17 July 2015). "The British Newspaper Archive Blog Crime and the Blitz | The British Newspaper Archive Blog". blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 16.

- ^ Porter, Roy (1994). London : a social history. Internet Archive. London: Hamish Hamilton. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-241-12944-9.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 31.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 68.

- ^ Ferguson 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Fortey, Richard (2008). Dry Storeroom No.1: The Secret Life of the Natural History Museum. New York: Vintage Books. p. 284. ISBN 9780307275523.

- ^ a b Leapman, Michael (2012). The Book of the British Library. London: The British Library. p. 61. ISBN 9780712358378.

- ^ a b c Bosman, Suzanne. "The Gallery in Wartime". National Gallery. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b Beardon 2013, p. 164.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 111.

- ^ Ferguson, Norman (2014). The Second World War : A Miscellany. Chichester, West Sussex: Summersdale. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-78372-251-8.

- ^ Ferguson 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 33.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 19.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 56-57.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 56.

- ^ Niko Gartner, "Administering'Operation Pied Piper'-how the London County Council prepared for the evacuation of its schoolchildren 1938-1939." Journal of Educational Administration & History 42#1 (2010): 17-32.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 58.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 60-61.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 62.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 46.

- ^ Ferguson 2014, p. 33-34.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 47.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 248.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 90.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 251.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 158.

- ^ a b c Ziegler 1998, p. 159.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 252.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 258.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 250.

- ^ a b c Ziegler 1998, p. 228.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 254.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 256.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 257.

- ^ a b Roy 1994, p. 338.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Brooks, Alan (2011). London at war : relics of the home front from the World Wars. Internet Archive. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Wharncliffe Books. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-84563-139-0.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 156.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Brooks 2011, p. 26.

- ^ a b Geoghegan, Tom (8 September 2010). "Did the Blitz really unify Britain?". BBC News. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 154.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 73-74.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 35.

- ^ a b "How St Paul's Cathedral survived the Blitz". BBC News. 29 December 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ "The Milkman: The Story behind One of the Most Iconic Images of the Blitz". warhistoryonline. 5 May 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 36-38.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 38.

- ^ Roy 1994, p. 340.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 49-50.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Brooks 2011, p. 51.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 50.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 51-52.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 56.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 155.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 59.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 160.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 60.

- ^ a b Beardon 2013, p. 163.

- ^ a b Brooks 2011, p. 62.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 64.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 31.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 165.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 72-74.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 29.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 36.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 110.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 112.

- ^ a b c Beardon 2013, p. 72.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 75.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 81.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 86-87.

- ^ Asbury, Jonathan (2020). Secrets of Churchill's War Rooms. London: Imperial War Museum. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-912423-14-9.

- ^ Asbury 2020, p. 10-11.

- ^ Asbury 2020, p. 13.

- ^ Asbury 2020, p. 16.

- ^ a b Asbury 2020.

- ^ Asbury 2020, p. 151.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 170.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 101.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 97.

- ^ K.E. Attar, "National Service: the University of London Library during the Second World War." Historical Research 89.245 (2016): 550-566.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 79.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 74-75.

- ^ a b Beardon 2013, p. 115.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 89-90.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 48.

- ^ Beardon, James (2013). The Spellmount Guide to London in the Second World War. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Spellmount. p. 14. ISBN 9780752493497.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 156-159.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 128-129.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 134-135.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 25-27.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 44.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 49-50.

- ^ a b Beardon 2013, p. 57.

- ^ Roy 1994, p. 341.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 44.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 97-98.

- ^ Ingleby, Matthew (2017). Bloomsbury: Beyond The Establishment. London: The British Library. pp. 101–102. ISBN 9780712356565.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 113.

- ^ Ingleby 2017, p. 104-105.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 75-76.

- ^ a b c Ziegler 1998, p. 96.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 97.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 213.

- ^ a b c Ziegler 1998, p. 215.

- ^ Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. London, New York: Hambledon Continuum. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-85285-417-1.

- ^ Ziegler, Philip (1998). London at war, 1939-1945. Internet Archive. London : Arrow. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-7493-1625-9.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 145-146.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 23.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 176.

- ^ "Kindertransport". The National Holocaust Centre and Museum. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 88.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 33-34.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 67.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 35-36.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 53-54.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 65.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 91.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 85.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 214.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 91-94.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 121.

- ^ a b Connelly, Mark (2012). Lee, Celia (ed.). Working, Queueing and Worrying: British Women and the Home Front, 1939-1945. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-1-84884-669-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 220.

- ^ Bérubé, Allan (1990). Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8078-7177-5.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 216.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 217.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 218.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 219.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 184.

- ^ Summerfield, Penny; Peniston-Bird, Corinna (2007). Contesting Home Defence: Men, Women and the Home Guard in the Second World War. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 62–84. ISBN 9780719062018.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 184-185.

- ^ Peniston-Bird 2013, p. 70.

- ^ Peniston-Bird, Corinna M. (2013). Noakes, Lucy (ed.). The people's war in personal testimony and in bronze: Sorority and the memorial to "The Women of World War II". Internet Archive. London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4411-4927-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 185.

- ^ a b Staveley-Wadham, Rose (30 November 2022). "The British Newspaper Archive Blog Blackout Crime | British Newspaper Archive". blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 77.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 92.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Richards, James (17 February 2011). "The Blitz: Sorting the Myth from the Reality". BBC History. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Noakes, Lucy (2013). British Cultural Memory and the Second World War. Internet Archive. London : Bloomsbury Academic. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4411-4927-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 169.

- ^ a b Ziegler 1998, p. 170.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 171.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 172.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 177.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 175.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 168.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 168-169.

- ^ Harries, Meirion; Harries, Susie (1983). The War Artists: British Official War Art of the Twentieth Century. London: Michael Joseph Ltd. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-7181-2314-7. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Harries & Harries 1983, p. 166.

- ^ Harries & Harries 1983, p. 181.

- ^ Harries & Harries 1983, p. 188.

- ^ Harries & Harries 1983, p. 192.

- ^ Harries & Harries 1983, p. 180.

- ^ Knott, Richard (2013). The Sketchbook War: Saving The Nation's Artists In WWII. Stroud: The History Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7524-8923-0.

- ^ Harries & Harries 1983, p. 186.

- ^ Harries & Harries 1983, p. 187.

- ^ Harries & Harries 1983, p. 194.

- ^ Delany, Paul (2004). Bill Brandt: A Life. Stanford University Press. pp. 168–170. ISBN 978-0-8047-5003-5.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 95.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 96.

- ^ Ziegler 1998, p. 333-334.

- ^ Brooks 2011, p. 114.

- ^ "These Fences Are Actually World War II-Era Stretchers". Atlas Obscura. 7 February 2019.

- ^ Beardon 2013, p. 177.