Malagasy language

| Malagasy | |

|---|---|

| malagasy | |

| Native to | Madagascar Comoros |

Native speakers | 25 million (2015)[1] |

| Latin script (Malagasy alphabet) Malagasy Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | mg |

| ISO 639-2 | mlg |

| ISO 639-3 | mlg – inclusive codeIndividual codes: xmv – Antankaranabhr – Barabuc – Bushimsh – Masikorobmm – Northern Betsimisarakaplt – Plateau Malagasyskg – Sakalavabzc – Southern Betsimisarakatdx – Tandroy-Mafahalytxy – Tanosytkg – Tesakaxmw – Tsimihety |

| Glottolog | mala1537 |

| Linguasphere | 31-LDA-a |

Malagasy (/mæləˈɡæsi/;[2] Malagasy pronunciation: [ˌmalaˈɡasʲ]) is an Austronesian language and the national language of Madagascar. Most people in Madagascar speak it as a first language as do some people of Malagasy descent elsewhere.

Classification

The Malagasy language is the westernmost member of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family.[3] Its distinctiveness from nearby African languages was already noted in 1708 by the Dutch scholar Adriaan Reland.[4]

It is related to the Malayo-Polynesian languages of Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, and specifically to the East Barito languages spoken in Borneo (e.g. Ma'anyan), with apparent influence from early Old Malay. There appears to be a Bantu influence or substratum in Malagasy phonotactics (Dahl 1988).

| Decimal numbers | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAN, circa 4000 BC | *isa | *DuSa | *telu | *Sepat | *lima | *enem | *pitu | *walu | *Siwa | *puluq |

| Malagasy | iray/isa | roa | telo | efatra | dimy | enina | fito | valo | sivy | folo |

| Ma'anyan | isa | rueh | telo | epat | dime | enem | pitu | balu | su'ey | sapulu |

| Kadazan | iso | duvo | tohu | apat | himo | onom | tu'u | vahu | sizam | hopod |

| Tagalog | isá | dalawá | tatló | ápat | limá | ánim | pitó | waló | siyám | sampu |

| Ilocano | maysá | dua | talló | uppát | limá | inném | pitó | waló | siam | sangapúlo |

| Chamorro | maisa/håcha | hugua | tulu | fatfat | lima | gunum | fiti | guålu | sigua | månot/fulu |

| Malay | satu | dua | tiga | empat | lima | enam | tujuh | lapan | sembilan | sepuluh |

| Javanese | siji | loro | telu | papat | limo | nem | pitu | wolu | songo | sepuluh |

| Tetum | ida | rua | tolu | haat | lima | neen | hitu | ualu | sia | sanulu |

| Fijian | dua | rua | tolu | vā | lima | ono | vitu | walu | ciwa | tini, -sagavulu |

| Tongan | taha | ua | tolu | fā | nima | ono | fitu | valu | hiva | -fulu |

| Samoan | tasi | lua | tolu | fa | lima | ono | fitu | valu | iva | sefulu |

Etymology

Malagasy is the demonym of Madagascar from which it is taken to refer to the people of Madagascar in addition to their language.

History

Madagascar was first settled by Austronesian peoples from Maritime Southeast Asia from the Sunda Islands (Malay archipelago).[5] As for their route, one possibility is that the Indonesian Austronesian came directly across the Indian Ocean from Java to Madagascar. It is likely that they went through the Maldives where evidence of old Indonesian boat design and fishing technology persists until the present.[6] The migrations continued along the first millennium, as confirmed by linguistic researchers who showed the close relationship between the Malagasy language and Old Malay and Old Javanese languages of this period.[7][8] The Malagasy language originated from Southeast Barito language, and Ma'anyan language is its closest relative, with numerous Malay and Javanese loanwords.[9][10] It is known that Ma'anyan people were brought as labourer and slaves by Malay and Javanese people in their trading fleets, which reached Madagascar by ca. 50-500 AD.[11][12] Far later, c. 1000, the original Austronesian settlers mixed with Bantus and Arabs, amongst others.[13] There is evidence that the predecessors of the Malagasy dialects first arrived in the southern stretch of the east coast of Madagascar.[14]

Malagasy has a tradition of oratory arts and poetic histories and legends. The most well-known is the national epic, Ibonia, about a Malagasy folk hero of the same name.[15]

Geographic distribution

Malagasy is the principal language spoken on the island of Madagascar. It is also spoken by Malagasy communities on neighboring Indian Ocean islands such as Réunion, Comoros and Mauritius. Expatriate Malagasy communities speaking the language also exist in Europe and North America, to a lesser extent, Belgium and Washington, DC in United States.

Legal status

The Merina dialect of Malagasy is considered the national language of Madagascar. It is one of two official languages alongside French in the 2010 constitution put in place the Fourth Republic. Previously, under the 2007 constitution, Malagasy was one of three official languages alongside French and English. Malagasy is the language of instruction in all public schools through grade five for all subjects, and remains the language of instruction through high school for the subjects of history and Malagasy language.

Dialects

There are two principal dialects of Malagasy; Eastern (including Merina) and Western (including Sakalava), with the isogloss running down the spine of the island, the south being western, and the central plateau and much of the north (apart from the very tip) being eastern. Ethnologue encodes 12 variants of Malagasy as distinct languages. They have about a 70% (~2000 years) similarity in lexicon with the Merina dialect.

Eastern Malagasy

The Eastern dialects are:

- Northern Betsimisaraka Malagasy (1,270,000 speakers) – spoken by the Betsimisaraka on the northeastern coast of the island

- Southern Betsimisaraka Malagasy (2,000,000 speakers) – spoken by the Betsimisaraka in the North of the region Vatovavy Fito Vinany.

- Plateau Malagasy (10,893,000 speakers) – spoken in the centre of the island and includes southeastern dialects like Antemoro and Antefasy. [16]

- Tanosy Malagasy (639,000 speakers) – spoken by the Antanosy people in the south of the island

- Tesaka Malagasy (1,130,000 speakers) – spoken by the Antaisaka people in the southeast of the island.[17]

Western Malagasy

The Western dialects are:

- Antankarana Malagasy (156,000 speakers) – spoken by the Antankarana in the northern tip of the island

- Bara Malagasy (724,000 speakers) – spoken by the Bara people in the south of the island

- Masikoro Malagasy (550,000 speakers) – spoken by the Masikoro in the southwest of the island

- Sakalava Malagasy (1,210,000 speakers) – spoken by the Sakalava people on the western coast of the island

- Tandroy-Mahafaly Malagasy (1,300,000 speakers) – spoken by the Antandroy and the Mahafaly people on the southern tip of the island

- Tsimihety Malagasy (1,615,000 speakers) – spoken by the Tsimihety people.[17]

Additionally, Bushi (41,700 speakers) is spoken on the French overseas territory of Mayotte,[18] which is part of the Comoro island chain situated northwest of Madagascar.

Region specific variations

The two main dialects of Malagasy are easily distinguished by several phonological features.

Sakalava lost final nasal consonants, whereas Merina added a voiceless [ə̥]:

- *tañan 'hand' → Sakalava [ˈtaŋa], Merina [ˈtananə̥]

Final *t became -[tse] in the one but -[ʈʂə̥] in the other:

- *kulit 'skin' → Sakalava [ˈhulitse], Merina [ˈhudiʈʂə̥]

Sakalava retains ancestral *li and *ti, whereas in Merina these become [di] (as in huditra 'skin' above) and [tsi]:

- *putiq 'white' → Sakalava [ˈfuti], Merina [ˈfutsi]

However, these last changes started in Borneo before the Malagasy arrived in Madagascar.

Writing system

The language has a written literature going back presumably to the 15th century. When the French established Fort-Dauphin in the 17th century, they found an Arabico-Malagasy script in use, known as Sorabe ("large writings"). This Arabic Ajami script was mainly used for astrological and magical texts. The oldest known manuscript in that script is a short Malagasy-Dutch vocabulary from the early 17th century, which was first published in 1908 by Gabriel Ferrand[19] though the script must have been introduced into the southeast area of Madagascar in the 15th century.[13]

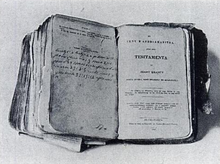

The first bilingual renderings of religious texts are those by Étienne de Flacourt,[20] who also published the first dictionary of the language.[21] Radama I, the first literate representative of the Merina monarchy, though extensively versed in the Arabico-Malagasy tradition,[22] opted in 1823 for a Latin system derived by David Jones and invited the Protestant London Missionary Society to establish schools and churches. The first book to be printed in Malagasy using Latin characters was the Bible, which was translated into Malagasy in 1835 by British Protestant missionaries working in the highlands area of Madagascar.[23]

The current Malagasy alphabet consists of 21 letters: a, b, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, v, y, z. The orthography maps rather straightforwardly to the phonemic inventory. The letters i and y both represent the /i/ sound (y is used word-finally, and i elsewhere), while o is pronounced /u/. The affricates /ʈʂ/ and /ɖʐ/ are written tr and dr, respectively, while /ts/ and /dz/ are written ts and j. The letter h is often silent. All other letters have essentially their IPA values. The letters c, q, u, w and x are all not used in native Malagasy words.

Mp and occasionally nt may begin a word, but they are pronounced /p, t/.

@ is used informally as a short form for amin'ny, which is a preposition followed by the definite form, meaning for instance with the.

| ـَ | ب | د | ـِ | ف | غ | ه | ـِ | ج | ك | ل | م | ن | ـُ | ڡ | ر | س | ط | و | ⟨ي⟩ & ⟨ز⟩ | ع | ⟨ڊ⟩ & ⟨رّ⟩ | ⟨̣ط⟩ & ⟨رّ⟩ | ت | ڡّ | طّ | ـَيْ | ـَوْ | ـُوً | ـُيْ | ⟨ـِيَا⟩ & ⟨ـِيْا⟩ | ـِوْ | ـِيْ |

| a | b | d | e | f | g, ng | h | i, y | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | t | v | z | n̈ | dr | tr | ts | mp | nt | ai | ao | oa | oi | ia, ea | io, eo | ie |

Diacritics

Diacritics are not obligatory in standard Malagasy, except in the case where its absence leads to an ambiguity: tanàna ("city") must have the diacritic to discriminate itself from tanana ("hand"). They may however be used in the following ways:

- ◌̀ (grave accent) shows the stressed syllable in a word. It is frequently used for disambiguation. For instance in tanàna (town) and tanana (hand), where the word that is an exception to the usual pronunciation rules (tanàna) gets an accent. Using accent on the word that follows the pronunciation rules (tànana) is less common, mainly in dictionaries. (This is very similar to the usage of the grave accent in Italian.)

- ◌́ (acute accent) may be used in

- very old dictionaries, along with grave accent

- dialects such as Bara

- French (Tuléar) and French-spelled (Antsirabé) names. Malagasy versions are Toliara or Toliary and Antsirabe.

- ◌̂ (circumflex) is used as follows:

- ô shows that the letter is pronounced /o/ and not /u/, in Malagasified foreign words (hôpitaly) and dialects (Tôlan̈aro). In standard Malagasy, ao or oa (as in mivoaka) is used instead.

- sometimes the single-letter words a and e are written â and ê but it does not change the pronunciation

- ◌̈ (diaeresis) is used with n̈ in dialects for a velar nasal /ŋ/. Examples are place names such as Tôlan̈aro, Antsiran̈ana, Iharan̈a, Anantson̈o. This can be seen in maps from FTM, the national institute of geodesy and cartography.

- ◌̃ (tilde) is used in ñ sometimes, perhaps when the writer cannot produce an n̈ (although ng is also used in such cases). In Ellis' Bara dialect dictionary, it is used for velar nasal /ŋ/ as well as palatal nasal /ɲ/.

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i, y /i/ |

o /u/ | |

| Mid | e /e/ |

ô, ao, oa /o/ | |

| Open | a /a/ |

After a stressed syllable, as at the end of most words and in the final two syllables of some, /a, u, i/ are reduced to [ə, ʷ, ʲ]. (/i/ is spelled ⟨y⟩ in such cases, though in monosyllabic words like ny and vy, ⟨y⟩ is pronounced as a full [i].) Final /a/, and sometimes final syllables, are devoiced at the end of an utterance. /e/ and /o/ are never reduced or devoiced. The large amounts of reduction of vowels and their effect on neighbouring consonants give Malagasy a phonological quality not unlike that of Portuguese.

/o/ is marginal in Merina dialect, found in interjections and loan words, though it is also found in place names from other dialectical areas. /ai, au/ are diphthongs [ai̯, au̯] in careful speech, [e, o] or [ɛ, ɔ] in more casual speech. /ai/, whichever way it is pronounced, affects following /k, ɡ/ as /i/ does.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ŋ ⟨n̈⟩ | |||||

| Plosive or affricate |

voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | ts ⟨ts⟩ | ʈʳ ⟨tr⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ||

| voiceless prenasalized | mp ⟨mp⟩ | nt ⟨nt⟩ |

nts ⟨nts⟩ | ɳʈʳ ⟨ntr⟩ | ŋk ⟨nk⟩ | |||

| voiced | b ⟨b⟩ | d ⟨d⟩ | dz ⟨j⟩ | ɖʳ ⟨dr⟩ | ɡ ⟨g⟩ | |||

| voiced prenasalized | mb ⟨mb⟩ | nd ⟨nd⟩ |

ndz ⟨nj⟩ | ɳɖʳ ⟨ndr⟩ | ŋɡ ⟨ng⟩ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | ||||

| voiced | v ⟨v⟩ | z ⟨z⟩ | ||||||

| Lateral | l ⟨l⟩ | |||||||

| Trill | r ⟨r⟩ | |||||||

The alveolars /s ts z dz l/ are slightly palatalized. /ts, dz, s, z/ vary between [ts, dz, s, z] and [tʃ, dʒ, ʃ, ʒ], and are especially likely to be the latter when followed by unstressed /i/: Thus French malgache [malɡaʃ] 'Malagasy'. The velars /k ɡ ŋk ŋɡ h/ are palatalized after /i/ (e.g. alika /alikʲa/ 'dog'). /h/ is frequently elided in casual speech.

The reported postalveolar trilled affricates /ʈʳ ɳʈʳ ɖʳ ɳɖʳ/ are sometimes simple stops, [ʈ ɳʈ ɖ ɳɖ], but they often have a rhotic release, [ʈɽ̊˔ ɳʈɽ̊˔ ɖɽ˔ ɳɖɽ˔]. It is not clear if they are actually trilled, or are simply non-sibilant affricates [ʈɻ̊˔ ɳʈɻ̊˔ ɖɻ˔ ɳɖɻ˔]. However, in another Austronesian language with a claimed trilled affricate, Fijian, trilling occurs but is rare, and the primary distinguishing feature is that it is postalveolar.[24] The Malagasy sounds are frequently transcribed [ʈʂ ɳʈʂ ɖʐ ɳɖʐ], and that is the convention used in this article.

In reduplication, compounding, possessive and verbal constructions, and after nasals, fricatives and liquids ('spirants') become stops, as follows:

| voiced | voiceless | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| spirant | stop | spirant | stop |

| v | b | f | p |

| l | d | ||

| z | dz | s | ts |

| r | ɖʳ (ɖʐ) | ||

| h | k | ||

Stress

Words are generally accented on the penultimate syllable, unless the word ends in ka, tra and often na, in which case they are stressed on the antepenultimate syllable. In many dialects, unstressed vowels (except /e/) are devoiced, and in some cases almost completely elided; thus fanorona is pronounced [fə̥ˈnurnə̥].

Grammar

Word order

Malagasy has a verb–object–subject (VOS) word order:

Mamaky boky ny mpianatra

(reads book the student)

"The student reads the book"

Nividy ronono ho an'ny zaza ny vehivavy

(bought milk for the child the woman)

"The woman bought milk for the child"

Within phrases, Malagasy order is typical of head-initial languages: Malagasy has prepositions rather than postpositions (ho an'ny zaza "for the child"). Determiners precede the noun, while quantifiers, modifying adjective phrases, and relative clauses follow the noun (ny boky "the book(s)", ny boky mena "the red book(s)", ny boky rehetra "all the books", ny boky novakin'ny mpianatra "the book(s) read by the student(s)").

Somewhat unusually, demonstrative determiners are repeated both before and after the noun ity boky ity "this book" (lit. "this book this").

Verbs

Verbs have syntactically three productive "voice" forms according to the thematic role they play in the sentence: the basic "agent focus" forms of the majority of Malagasy verbs, the derived "patient focus" forms used in "passive" constructions, and the derived "goal focus" forms used in constructions with focus on instrumentality. Thus

- (1) Manasa ny tanako amin'ny savony aho. ("I am washing my hands with soap.")

- (2) Sasako amin'ny savony ny tanako. ("My hands are washed with soap by me.")

- (3) Anasako ny tanako ny savony. ("It is with soap that my hands are washed by me.")

all mean "I wash my hands with soap" though focus is determined in each case by the sentence initial verb form and the sentence final (noun) argument: manasa "wash" and aho "I" in (1), sasako "wash" and ny tanako "my hands" in (2), anasako "wash" and ny savony "soap" in (3). There is no equivalent to the English preposition with in (3).

Verbs inflect for past, present, and future tense, where tense is marked by prefixes (e.g. mividy "buy", nividy "bought", hividy "will buy").

Nouns and pronouns

Malagasy has no grammatical gender, and nouns do not inflect for number. However, pronouns and demonstratives have distinct singular and plural forms (cf. io boky io "that book", ireto boky ireto "these books").

There is a complex series of personal and demonstrative pronouns, depending on the speaker's familiarity and closeness to the referent.

Deixis

Malagasy has a complex system of deixis (these, those, here, there, etc.), with seven degrees of distance as well as evidentiality across all seven. The evidential dimension is prototypically visible vs. non-visible referents; however, the non-visible forms may be used for visible referents which are only vaguely identified or have unclear boundaries, whereas the visible forms are used for non-visible referents when these are topical to the conversation.[25]

| PROX | MED | DIST | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverbs (here, there) |

NVIS | atỳ | àto | ào | àtsy | àny | aròa* | arỳ |

| VIS | etỳ | èto | èo | ètsy | èny | eròa | erỳ | |

| Pronouns (this, that) (these, those) |

NVIS | izatỳ* | izàto* | izào | izàtsy* | izàny | izaròa* | izarỳ* |

| VIS | itỳ | ìto | ìo | ìtsy | ìny | iròa* | irỳ | |

| VIS.PL | irèto | irèo | irètsy | irèny | ireròa* | irerỳ* | ||

Notes:

- Diacritics in deixis are not mandatory in Malagasy.

- Deixis marked by a * are rarely used.

Vocabulary

Malagasy shares much of its basic vocabulary with the Ma'anyan language, a language from the region of the Barito River in southern Borneo. The Malagasy language also includes some borrowings from Arabic and Bantu languages (especially the Sabaki branch, from which most notably Swahili derives), and more recently from French and English.

The following samples are of the Merina dialect or Standard Malagasy, which is spoken in the capital of Madagascar and in the central highlands or "plateau", home of the Merina people.[26][27] It is generally understood throughout the island.

| English | Malagasy | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| English | Anglisy | ãŋˈɡliʂ |

| Yes | Eny | ˈʲenj |

| No | Tsia, (before a verb) Tsy | tsi, tsʲ |

| Hello! / How are you? | Manao ahoana! | manaˈʷonə̥/manaˈonə̥ |

| Hello! (rural areas) | Salama! | saˈlamə̥ |

| I'm fine, thank you. | Tsara fa misaotra. | ˈtsarə̥ fa mʲˈsoːtʂə̥ |

| Goodbye! | Veloma! | veˈlumə̥ |

| Please | Azafady | azaˈfadʲ |

| Thank you | Misaotra | mʲˈsoːtʂa |

| You're welcome | Tsisy fisaorana. | tsʲ ˈmisʲ fʲˈsoːranə̥ |

| Excuse me | Azafady (with arm and hand pointing to the ground) | azaˈfadʲ |

| Sorry | Miala tsiny | mjala ˈtsinʲ |

| Who? | Iza? | ˈiːza/ˈiza |

| What? | Inona? | inːa |

| When? | Rahoviana?, (past tense) Oviana | roːˈvinə̥/rawˈvinə̥ |

| Where? | Aiza?, (past tense) Taiza | ajzə̥ |

| Why? | Fa maninona? | fa maninːə̥ |

| How? | Ahoana? | aˈʷonə̥ |

| How many? | Firy? | ˈfirʲ |

| How much? | Ohatrinona? | ʷoˈtʂinːə̥ |

| What's your name? | Iza ny anaranao? | iza njanaraˈnaw |

| For | Ho an'ny / Ho an'i | wanːi |

| Because | Satria | saˈtʂi |

| I don't understand. | Tsy mazava, Tsy azoko. | tsʲ mazavə̥ |

| Yes, I understand. | Eny, mazava, Eny, azoko | ʲenʲ mazavə̥ |

| Help! | Vonjeo! | vunˈdzew |

| Go away! | Mandehana! | man di anə |

| Can you help me please? | Afaka manampy ahy ve ianao azafady? | afaka manapʲ a ve enaw azafadʲ |

| Where are the toilets? | Aiza ny efitrano fivoahana?, Aiza ny V.C.?, Aiza ny toilet? | ajza njefitʂanʷ fiˈvwaːnə̥ |

| Do you speak English? | Mahay teny anglisy ve ianao? | miˈtenʲ ãŋˈɡliʂ ve eˈnaw |

| I do not speak Malagasy. | Tsy mahay teny malagasy aho. | tsʲ maaj tenʲ malaˈɡasʲ a |

| I do not speak French. | Tsy mahay teny frantsay aho. | tsʲ maaj tenʲ frantsaj a |

| I am thirsty. | Mangetaheta aho. | maŋɡetaˈeta |

| I am hungry. | Noana aho. | noːna |

| I am sick. | Marary aho. | |

| I am tired. | Vizaka aho, Reraka aho | ˈvizaka, rerakau |

| I need to pee. | Poritra aho, Ny olombelona tsy akoho | purtʂa |

| I would like to go to Antsirabe. | Te hankany Antsirabe aho. | tiku ankanʲ anjantsirabe |

| That's expensive! | Lafo be izany! | lafʷˈbe zanʲ |

| I'm hungry for some rice. | Noana vary aho. | noːna varja |

| What can I do for you? | Inona no azoko atao ho anao? | inːa ɲazʷkwataʷ wanaw |

| I like... | Tiako... | tikʷ |

| I love you. | Tiako ianao. | tikwenaʷ |

| Numbers | ||

| one | isa/iray | isə̥ |

| two | roa | ru |

| three | telo | telʷ |

| four | efatra | ˈefatʂə̥ |

| five | dimy | ˈdimʲ |

| six | enina | enː |

| seven | fito | fitʷ |

| eight | valo | valʷ |

| nine | sivy | sivʲ |

| ten | folo | fulʷ |

| eleven | iraika ambin'ny folo | rajkʲambefulʷ |

| twelve | roa ambin'ny folo | rumbefulʷ |

| twenty | roapolo | ropulʷ |

| thirty | telopolo | telopulʷ |

| forty | efapolo | efapulʷ |

| fifty | dimampolo | dimapulʷ |

| sixty | enim-polo | empulʷ |

| seventy | fitopolo | fitupulʷ |

| eighty | valopolo | valupulʷ |

| ninety | sivifolo | sivfulʷ |

| one hundred | zato | zatʷ |

| two hundred | roan-jato | rondzatʷ |

| one thousand | arivo | arivʷ |

| ten thousand | iray alina | rajal |

| one hundred thousand | iray hetsy | rajetsʲ |

| one million | iray tapitrisa | rajtaptʂisə̥ |

| one billion | iray lavitrisa | rajlavtʂisə̥ |

| 3,568,942 | roa amby efapolo sy sivin-jato sy valo arivo sy enina alina sy dimy hetsy sy telo tapitrisa | rumbefapulʷ sʲsivdzatʷ sʲvalorivʷ sʲenːal sʲdimjetsʲ sʲtelutapitʂisə̥ |

Lexicography

The first dictionary of the language is Étienne de Flacourt's Dictionnaire de la langue de Madagascar published in 1658 though earlier glossaries written in Arabico-Malagasy script exist. A later Vocabulaire Anglais-Malagasy was published in 1729. An 892-page Malagasy–English dictionary was published by James Richardson of the London Missionary Society in 1885, available as a reprint; however, this dictionary includes archaic terminology and definitions. Whereas later works have been of lesser size, several have been updated to reflect the evolution and progress of the language, including a more modern, bilingual frequency dictionary based on a corpus of over 5 million Malagasy words.[26]

- Winterton, M. et al.: Malagasy–English, English–Malagasy Dictionary / Diksionera Malagasy–Anglisy, Anglisy–Malagasy. Raleigh, North Carolina. USA: Lulu Press 2011, 548 p.

- Richardson: A New Malagasy–English Dictionary. Farnborough, England: Gregg Press 1967, 892 p. ISBN 0-576-11607-6 (Original edition, Antananarivo: The London Missionary Society, 1885).

- Diksionera Malagasy–Englisy. Antananarivo: Trano Printy Loterana 1973, 103 p.

- An Elementary English–Malagasy Dictionary. Antananarivo: Trano Printy Loterana 1969, 118 p.

- English–Malagasy Phrase Book. Antananarivo: Editions Madprint 1973, 199 p. (Les Guides de Poche de Madagasikara.)

- Paginton, K: English–Malagasy Vocabulary. Antananarivo: Trano Printy Loterana 1970, 192 p.

- Bergenholtz, H. et al.: Rakibolana Malagasy–Alemana. Antananarivo: Leximal/Moers: aragon. 1991.

- Bergenholtz, H. et al.: Rakibolana Alemana–Malagasy. Antananarivo: Tsipika/Moers: aragon. 1994.

- Rakibolana Malagasy. Fianarantsoa: Régis RAJEMISOA – RAOLISON 1995, 1061 p.

See also

References

- ^ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- ^ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- ^ Malagasy's family tree on Ethnologue

- ^ Blench, Roger (2007). "New Palaeozoogeographical Evidence for the Settlement of Madagascar" (PDF). Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 42 (1): 69–82. doi:10.1080/00672700709480451. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21.

- ^ Ricaut, François-X; Razafindrazaka, Harilanto; Cox, Murray P; Dugoujon, Jean-M; Guitard, Evelyne; Sambo, Clement; Mormina, Maru; Mirazon-Lahr, Marta; Ludes, Bertrand; Crubézy, Eric (2009). "A new deep branch of eurasian mtDNA macrohaplogroup M reveals additional complexity regarding the settlement of Madagascar". BMC Genomics. 10 (1): 605. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-605. PMC 2808327. PMID 20003445.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ P. Y. Manguin. Pre-modern Southeast Asian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: The Maldive Connection. ‘New Directions in Maritime History Conference’ Fremantle. December 1993.

- ^ Adelaar, K. Alexander; Himmelmann, Nikolaus, eds. (2005). The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1286-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Simon, Pierre R. (2006). Fitenin-drazana. L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-01108-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Otto Chr. Dahl, Malgache et Maanjan: une comparaison linguistique, Egede-Instituttet Avhandlinger, no. 3 (Oslo: Egede-Instituttet, 1951), p. 13.

- ^ There are also some Sulawesi loanwords, which Adelaar attributes to contact prior to the migration to Madagascar: See K. Alexander Adelaar, “The Indonesian Migrations to Madagascar: Making Sense of the Multidisciplinary Evidence”, in Truman Simanjuntak, Ingrid Harriet Eileen Pojoh and Muhammad Hisyam (eds.), Austronesian Diaspora and the Ethnogeneses of People in Indonesian Archipelago, (Jakarta: Indonesian Institute of Sciences, 2006), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Dewar, Robert E.; Wright, Henry T. (1993). "The culture history of Madagascar". Journal of World Prehistory. 7 (4): 417–466. doi:10.1007/bf00997802. hdl:2027.42/45256.

- ^ Burney DA, Burney LP, Godfrey LR, Jungers WL, Goodman SM, Wright HT, Jull AJ (August 2004). "A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (1–2): 25–63. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005. PMID 15288523.

- ^ a b Ferrand, Gabriel (1905), "Les migrations musulmanes et juives à Madagascar", Revue de l'histoire des religions, Paris

- ^ Serva, Maurizio; Petroni, Filippo; Volchenkov, Dima; Wichmann, Søren. "Malagasy Dialects and the Peopling of Madagascar". arXiv:1102.2180.

- ^ "La traduction de la Bible malgache encore révisée" [The translation of the Malagasy Bible is still being revised]. haisoratra.org (in French). 3 May 2007. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ "Antanosy in Madagascar". Joshua Project.

- ^ a b "Madagascar". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ^ "Bushi". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- ^ Ferrand, Gabriel (1908). "Un vocabulaire malgache-hollandais." Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde van Nederlandsch Indië 61.673-677. The manuscript is now in the Arabico-Malagasy collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- ^ Flacourt, Étienne de (1657). Le Petit Catéchisme madécasse-français.Paris;(1661). Histoire de la grande isle Madagascar.Paris, pp.197–202.

- ^ Flacourt, Étienne de (1658). Dictionnaire de la langue de Madagascar. Paris.

- ^ Berthier, H.J. (1934). De l'usage de l'arabico=malgache en Imérina au début du XIXe siècle: Le cahier d'écriture de Radama Ier. Tananarive.

- ^ The translation is due to David Griffith of the London Missionary Society, with corrections in 1865–1866."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 131. ISBN 0-631-19815-6.

- ^ Janie Rasoloson and Carl Rubino, 2005, "Malagasy", in Adelaar & Himmelmann, eds, The Austronesian languages of Asia and Madagascar

- ^ a b [1] Winterton, Matthew et al. (2011). Malagasy–English, English–Malagasy Dictionary / Diksionera Malagasy–Anglisy, Anglisy–Malagasy. Lulu Press.

- ^ Rasoloson, Janie (2001). Malagasy–English / English–Malagasy: Dictionary and Phrasebook. Hippocrene Books.

Sources

- Biddulph, Joseph (1997). An Introduction to Malagasy. Pontypridd, Cymru. ISBN 978-1-897999-15-8.

- Houlder, John Alden, Ohabolana, ou proverbes malgaches. Imprimerie Luthérienne, Tananarive 1960.

- Hurles, Matthew E.; et al. (2005). "The Dual Origin of the Malagasy in Island Southeast Asia and East Africa: Evidence from Maternal and Paternal Lineages". American Journal of Human Genetics. 76: 894–901. doi:10.1086/430051. PMC 1199379. PMID 15793703.

- Ricaut et al. (2009) "A new deep branch of eurasian mtDNA macrohaplogroup M reveals additional complexity regarding the settlement of Madagascar", BMC Genomics.

External links

- Malagasy-English, English–Malagasy bilingual frequency dictionary

- Large audio database of Malagasy words with recorded pronunciation

- Searchable Malagasy–French–English Dictionary/Translator

- Malagasy–English Dictionary

- Malagasy–French dictionary

- Malagasy Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Malagasy Vocabulary List (from the World Loanword Database)

- La Bible Malgache en texte intégral – the complete text of the 1865 Malagasy Bible

- List of references on Malagasy language (with links to online resources).

- Oxford University: Malagasy Language

- Paper on Malagasy clause structure