Aloha Stadium

| |

Looking south in September 2005 | |

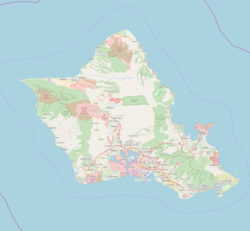

Location on the island of Oahu | |

| Address | 99–500 Salt Lake Boulevard |

|---|---|

| Location | Halawa, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 21°22′23″N 157°55′48″W / 21.373°N 157.93°W |

| Public transit | at Aloha Stadium (planned 2020) |

| Owner | State of Hawaii |

| Operator | Hawaii Stadium Authority |

| Capacity | 50,000[1] |

| Field size | Baseball Left Field – 325 ft (99 m) Center Field – 420 ft (128 m) Right Field – 325 ft (99 m) |

| Surface | S5 (2011–present) FieldTurf (2003–2011)[2] AstroTurf (1975–2002) |

| Construction | |

| Opened | September 12, 1975[6][7] |

| Construction cost | $37 million[3] ($210 million in 2023[4]) |

| Architect | Luckman Partnership, Inc.[5] |

| Tenants | |

| Hawaii Rainbow Warriors (NCAA) (1975–present) The Hawaiians (WFL) (1975) Hula Bowl (NCAA) (1975–1997, 2006–2008, 2020–present) Hawaii Islanders (PCL) (1976–1987) Team Hawaii (NASL) (1977) Aloha Bowl (NCAA) (1982–2000) Oahu Bowl (NCAA) (1998–2000) Hawaiʻi Bowl (NCAA) (2002–present) St. Louis Crusaders (ILH) Pro Bowl (NFL) (1980–2009, 2011–2014, 2016) Kanaloa Hawai’i (MLR) (TBA) | |

Aloha Stadium is a multi-purpose stadium located in Halawa, Hawaii, a western suburb of Honolulu (though with a Honolulu address). It is the largest stadium in the state of Hawaii. Aloha Stadium is home to the University of Hawaiʻi Rainbow Warriors football team (Mountain West Conference, NCAA Division I FBS).

It hosts the NCAA's Hawaiʻi Bowl (2002–present) and Hula Bowl (restarting in 2020,[8] previously hosted 1975–1997 and 2006–2008), and formerly was home to the National Football League's Pro Bowl from 1980 through 2016 (except in 2010 and 2015). It also hosts numerous high school football games during the season, and serves as a venue for large concerts and events, including high school graduation ceremonies. A swap meet in the stadium's parking lot every Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday draws large crowds.[9]

Aloha Stadium was home field for the AAA Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League (PCL) from 1975 to 1987, before the team moved to Colorado Springs.

History

Before 1975, Honolulu's main outdoor stadium had been Honolulu Stadium, a wooden stadium on King Street. However, it had reached the end of its useful life by the 1960s, and was well below the standards for Triple-A baseball. The need for a new stadium was hastened by the Rainbows' move to NCAA Division I. Located west of downtown Honolulu and 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Honolulu International Airport, Aloha Stadium was constructed in 1975 at a cost of $37 million. The baseball field is aligned north-northwest (home plate to centerfield), as is the football field.

The first sporting event at Aloha Stadium was a college football game between Hawaii and Texas A&I (now Texas A&M-Kingsville) on September 13, 1975.[6] Played on Saturday night, the crowd was 32,247,[10] and the visitors prevailed, 43–9.[6]

The stadium was somewhat problematic for its initial primary tenant, the baseball Islanders. Located in west-central Oahu, it was far from the team's fan base, and many were unwilling to make the drive. Additionally, while TheBus stopped at the main gate of Honolulu Stadium, the stop for Aloha Stadium was located some distance from the gate. As a result, attendance plummeted and never really recovered—a major factor in the franchise's ultimate move to the mainland.[11]

Additionally, stadium management initially refused to allow the use of metal spikes on the AstroTurf in May 1976. When the Tacoma Twins complied with a parent-club directive to wear the spikes, stadium management turned off the center field lights. After 35 minutes, the umpires forfeited the game to the Twins. The Islanders protested, claiming they had no control over the lights. However, the PCL sided with the Twins, citing a league rule that the home team is responsible for providing acceptable playing facilities.[11][12] The teams ended the season in a tie for first in the Western Division and Hawaii won the one-game playoff in Tacoma.

As originally built, Aloha Stadium had various configurations for different sport venues and other purposes. Four movable 7,000-seat sections, each 3.5 million pounds (1,600,000 kg) [1] could move using air casters into a diamond configuration for baseball (also used for soccer), an oval for football, or a triangle for concerts. In January 2007, the stadium was permanently locked into its football configuration due to cost and maintenance issues.[13] An engineer from Rolair Systems, the NASA spin-off company that engineered the system,[14] claims that the problem was caused by a concrete contractor that ignored specifications for the concrete pads under the stadium.[15]

There have been numerous discussions with Hawaii lawmakers who are concerned with the physical condition of the stadium. There are several issues regarding rusting of the facility, several hundred seats that need to be replaced, and restroom facilities that need to be expanded to accommodate more patrons.[3] Much of the rust is due to building the stadium with weathering steel. It was intended to create a protective patina that would eliminate the need for painting. However, the designers reckoned without Honolulu's ocean-salt laden climate. As a result, the steel has never stopped rusting.

A 2005 study by Honolulu engineering firm Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. determined that the stadium required $99 million to be completely restored and an additional $115 million for ongoing maintenance and refurbishment over the next 20 years to extend its useful life.[16] In early 2007, the state legislature proposed to spend $300 million to build a new facility as opposed to spending approximately $216 million to extend the life of Aloha Stadium for another 20–30 years. The new stadium may also be used to attempt to lure a Super Bowl to Hawaii in the future.[17]

One council member has said that if immediate repairs are not made within the next seven years, then the stadium will probably have to be demolished due to safety concerns. In May 2007, the state allotted $12.4 million to be used towards removing corrosion and rust from the structure.[18]

Expansion and improvements

In 2003, the stadium surface was changed from AstroTurf (which had been in place since the stadium opened) to FieldTurf.[2] In July 2011, the field was replaced with an Act Global UBU Sports Speed S5-M synthetic turf system.

In 2008, the state of Hawaii approved the bill of $185 million to refurbish the aging Aloha Stadium.[19] In 2010, Aloha Stadium completely retrofitted its scoreboard and video screen to be more up to date with its high definition capability. The Aloha Stadium Authority plans to add more luxury suites, replacing all seats, rusting treatments, parking lots, more restrooms, pedestrian bridge supports, enclosed lounge, and more. There is also a proposal that would close the 4 openings in the corners of the stadium to add more seats.

In 2011, the playing field was refurbished in part due to a naming rights sponsorship from Hawaiian Airlines. As a result of the sponsorship deal, the field was referred to as Hawaiian Airlines Field at Aloha Stadium.[20]

The airline did not renew sponsorship after the deal expired in 2016. As a result, the field went unnamed until late August, when Hawaiian Tel Federal Credit Union signed a 3-year/$275,000 agreement. As of 2016, the field is now known as Hawaiian Tel Federal Credit Union Field at Aloha Stadium.[21]

In early 2017, there was a study in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser about replacing Aloha Stadium due to safety concerns and a liability risk. The plan is to build a smaller 30,000 seat stadium on the existing property and also build commercial development around the stadium. In theory, it would save the state millions of dollars instead of renovating and keep the existing stadium as it is.[22][23]

In July 2019, Hawaii Gov. David Ige signed Act 268 into law, appropriating $350 million for an Aloha Stadium redevelopment project. The funds will go toward the construction of a new stadium and land development, including a mixed-use sports and entertainment complex.[24]

Events

American football

In 1975, Aloha Stadium was home to the World Football League's Hawaiians. The San Francisco 49ers and the San Diego Chargers played an NFL preseason game at Aloha Stadium on August 21, 1976.

In August 2019, the NFL returned to Aloha Stadium with a preseason game between the Los Angeles Rams and Dallas Cowboys.[25]

Baseball

In 1997, a three-game regular season series between Major League Baseball's St. Louis Cardinals and San Diego Padres was held at the stadium.[26] The series was played as a doubleheader on April 19 and a nationally broadcast (ESPN) game on April 20. In 1975, the Padres had played an exhibition series against the Seibu Lions of Japan's Pacific League.

Soccer

Aloha Stadium hosted the inaugural Pan-Pacific Championship (February 20–23, 2008), a knockout soccer tournament, involving four teams from Japan's J-League, North America's Major League Soccer (MLS) and Australia/New Zealand's A-League.[27] The 2012 Hawaiian Islands Invitational was also held at the venue.

The United States women's national soccer team was scheduled play a game against Trinidad and Tobago as part of their World Cup Winning Victory Tour at the stadium on December 6, 2015; however, the game was canceled the day before gameday due to concerns over the turf being unsafe to play on.[28]

Rugby league

On June 2, 2013, the stadium played host to a rugby league test match where Samoa defeated the USA 34–10.[29]

In June, the Brisbane Broncos from the Australasian-based National Rugby League (NRL) competition organized for a rugby league match to be played at Aloha Stadium against NRL rivals Penrith Panthers later in 2015.[30] However, in September the NRL blocked the idea and the game didn't go ahead.[31]

Major League Rugby

A proposed Major League Rugby team, Kanaloa Hawai’i is planned to be based at Aloha Stadium.[32][33]

Graduation ceremonies

Aloha Stadium is also the venue for five public high school graduation ceremonies: Radford High School, Mililani High School, Aiea High School, James Campbell High School, and Pearl City High School.

Concerts

| Date | Artist | Opening act(s) | Tour / Concert name | Attendance | Revenue | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 25, 1984 | The Police | — | Synchronicity Tour | — | — | |

| November 6, 1995 | The Eagles | — | Hell Freezes Over Tour | — | — | |

| January 3, 1997 | Michael Jackson | — | HIStory World Tour | 35,000 | — | These were his only US shows that decade. Also, the first person to sell out the stadium.[34] |

| January 4, 1997 | 35,000 | |||||

| May 3, 1997 | Gloria Estefan | — | Evolution World Tour | — | — | |

| May 29, 1997 | Whitney Houston | Bobby Brown | Pacific Rim Tour | 29,118 / 29,118 | $1,634,370 | Bobby Brown opened up the show singing his hit tunes. Whitney was in disguise singing background vocals for Bobby. According to audience members, "when she came out, the crowd went wild. She sang very well even though she had a cold. She closed the show with "Step by Step".[35] |

| January 23, 1998 | The Rolling Stones | Jonny Lang | Bridges To Babylon Tour | 54,006 / 60,000 | $3,317,190 | |

| January 24, 1998 | ||||||

| February 21, 1998 | Mariah Carey | — | Butterfly World Tour | 30,415 / 30,415 | $1,744,210 | [36] |

| January 30, 1999 | Janet Jackson | 98 Degrees | The Velvet Rope Tour | 38,224 / 38,224 | $2,664,000 | The capacity for this show was expanded from the original capacity of 35,000 to 38,000 to meet the high ticket demand.[37][38] |

| February 12, 1999 | Celine Dion | — | Let's Talk About Love World Tour | — | — | |

| December 31, 1999 | Michael Jackson | - | Millennium Concert | |||

| February 16, 2002 | Janet Jackson | Ginuwine | All for You Tour | 32,211 / 33,511 | $1,472,935 | This concert was aired on HBO the following night and was later released on DVD and VHS, titled Janet: Live in Hawaii.[39][40] Missy Elliott also made a surprise appearance. |

| December 9, 2006 | U2 | Pearl Jam Rocco and the Devils |

Vertigo Tour | 45,815 / 45,815 | $4,486,532 | The band's first concert in Hawaii since 1985. Billie Joe Armstrong of Green Day was the special guest.[41] |

| November 8, 2018 | Bruno Mars | The Green Common Kings |

24K Magic World Tour | 113,751 / 113,751 | $12,394,580 | |

| November 10, 2018 | ||||||

| November 11, 2018 | ||||||

| December 7, 2018 | The Eagles | Jack Johnson | All the Light Above it Too World Tour | — | — | |

| December 8, 2018 | Guns N' Roses | — | Not in This Lifetime... Tour | 22,485 / 23,000 | — | |

| February 15, 2019 | Eminem | — | — | 31,621 / 31,621 | $3,089,448 |

See also

References

- ^ a b "Hawaii Athletics – Aloha Stadium". Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Masuoka, Brandon (April 29, 2003). "Aloha Stadium surface will be of NFL quality". The Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ a b Gima, Craig (January 27, 2006). "Stadium corrosion creates a $129M safety concern". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Muschamp, Herbert (January 28, 1999). "Charles Luckman, Architect Who Designed Penn Station's Replacement, Dies at 89". The New York Times. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Texas A and I crushes Hawaii". The Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. September 15, 1975. p. 15.

- ^ "Aloha Stadium – Trivia". Archived from the original on August 5, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Hula Bowl returning to Aloha Stadium after 11-year hiatus". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- ^ "Hawaii's premier Aloha Stadium Swap Meet an Outdoor Market in Hawaii|Aloha Outdoor Market, Flea Markets and Swap meet for shopping in Honolulu". Alohastadiumswapmeet.net. September 12, 1975. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ "Aloha Stadium Swap Meet "About Us" page". alohastadiumswapmeet.net. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009.

- ^ a b Kaneshiro, Stacy (July 4, 2009). "Islanders a fan hit during 27-year run". The Honolulu Advertiser.

- ^ Stewart, Chuck (September 1, 1976). "Sport Stew". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Spokane, Washington. p. 35 – via Google News.

- ^ Masuoka, Brandon (July 28, 2006). "Aloha Stadium losing baseball configuration". The Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ "Convertible Stadium". NASA. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ Kieding, Bob (2012). "Moving Seats". Popular Science (October). Wright's Media: 8.

- ^ "Stadium rust to get $12.4M treatment". The Honolulu Advertiser. May 11, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ Reardon, Dave (April 3, 2006). "Super Dreams: Bringing the 50th Super Bowl to the 50th state would be costly". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ Arakawa, Lynda (May 11, 2007). "Stadium rust to get $12.4M treatment". The Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ Masuoka, Brandon (June 27, 2008). "Hawaii stadium to get $185M overhaul; UH expands pay-per-view package". Honolulu Advertiser. ISSN 1072-7191. OCLC 8807414. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- ^ Hawaiian Airlines Grabs Naming Rights To Aloha Stadium Field; SponsorPitch; 08-04-2011 Archived 2011-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Credit union buys naming rights for Aloha Stadium field". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. August 26, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Study recommends smaller venue to replace Aloha Stadium". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ "Report: Aloha Stadium now a 'liability,' cheaper to build new stadium". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ Peterkin, Olivia (May 11, 2019). "Gov. Ige signs bill appropriating $350M to Aloha Stadium redevelopment project". Pacific Business News. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- ^ Klein, Gary (March 21, 2019). "Rams to play Cowboys in Hawaii in Aug. 17 preseason game". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ Arnett, Paul; Yuen, Mike (February 25, 1997). "Padres, Cardinals to play in Hawaii". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ Carlos Alvarez-Galloso, Roberto (December 26, 2007). "2008 Pan-Pacific Championship: Make it more inclusive". MeriNews. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Soccer Cancels Dec. 6 Match against T&T in Hawaii Due to Field Conditions". US Soccer. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ "Tomahawks get ready for match-up with Na Toa Samoa at Aloha Stadium". KHON2. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ "Broncos Panthers To Play Match In Hawaii". triplem.com.au. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Exhibition matches are a bad idea in the USA – just look at the Wallabies!". theroar.com.au. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Professional rugby reaches Hawaii - Rugby World magazine".

- ^ "Pacific-owned Kanaloa Hawaii set to join Major League Rugby | RNZ News".

- ^ "King of Pop ends Hawaiian tour". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. (South Carolina). January 7, 1997. p. A2.

- ^ "The Pacific Rim Tour info". allwhitney.com. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ^ Events. Travel Hawaii for Smartphones and Mobile Devices – Illustrated Travel Guide. January 1, 2007. ISBN 978-1-60501-043-4. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Tickets still available for Janet concert". The Honolulu Advertiser. February 8, 2002. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ "Hawai'i-born dancer has Janet moving to his beat". Hawaii Advertiser. February 15, 2002. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ "Janet Heads To Hawaii For HBO Live Special". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- ^ "Music DVD Review: Janet Jackson – Live in Hawaii (Re-Release)". Blog Critics. March 31, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "U2 Honolulu, 2006-12-09, Aloha Stadium, Vertigo Tour - U2 on tour". U2gigs.com. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

External links

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by first stadium

|

Host of the Hawaiʻi Bowl 2002–present |

Incumbent |

| Preceded by | Host of the NFL Pro Bowl 1980–2009 2011–2014 2016 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by first stadium

|

Host of the Pan-Pacific Championship 2008 |

Succeeded by |

| |

Location on the island of Oahu | |

| Location | University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 21°17′38″N 157°49′05″W / 21.294°N 157.818°W{{#coordinates:}}: cannot have more than one primary tag per page |

| Owner | University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa |

| Operator | Hawaii Rainbow Warriors and Rainbow Wahine |

| Capacity | 4,100 (2015–2020) 9,346 (2021–2022) 15,194 (2023) 16,909 (2024–future) |

| Opened | 2015 |

| Tenants | |

| Hawaii Rainbow Warriors and Rainbow Wahine (NCAA) Beach volleyball (2015–present) Track and field (2015–present) Women's soccer (2015–present) Football (2021–present)[1] Hawaiʻi Bowl (NCAA) (2022–present) | |

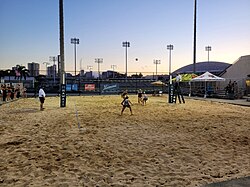

The Clarence T. C. Ching Athletics Complex, located on the campus of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa in Honolulu, features a three-story building next to an all-purpose track and Clarence T. C. Ching Field.[2][3][4] The facility, built in 2015, includes locker rooms and a meeting room for Hawaii beach volleyball, cross country, women's soccer and track and field teams.[5][6]

The university's football team also utilizes the facility for practices, and it became the team’s temporary stadium starting in 2021. The stadium has a seating capacity of 15,194, up from 9,346 in 2021 and 2022. It will further expand to 16,909 in 2024.[5]

History

The complex replaced the university's former sports facility, Cooke Field, following a $5 million donation from the foundation established by Hawaii real estate developer Clarence T. C. Ching (1912–1985).[7] This was a record donation for the university's athletics program.[8][9] This donation was intended to cover half the estimated $10 million cost of the development, due to open in 2013. However, project delays mean the complex ran 60% over budget and did not open until 2015. The remainder of the budget was covered by the university and the state of Hawaii.[10]

The delay led to threats from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) to decertify the institution's athletic department, given the lack of women's sports facilities. A key aspect of the new complex was to better serve women's athletics at Manoa, in particular the women's soccer team which previously played on a non-NCAA-compliant field.[11][12][13]

Uses

The athletics complex serves as the home field for the university's women's soccer team. It also has a 778-seat beach volleyball venue with two competition courts,[2] used by the university's beach volleyball team.[5] The venue also serves as a cross country course.[14] The field and its surrounding track function as the outdoor track and field facility for the university.[2][14]

College football

The complex normally serves as the practice facility for the university's football team. In December 2020, issues with Aloha Stadium (home venue of the football team since 1975) led to that venue halting the scheduling of new events.[15] As a result, the team announced plans to play home games on campus at the athletics complex "for at least the next three years".[16] Prior to the 2021 season, the university prepared the complex for home football games, including increasing seating capacity, replacing the existing turf, installing a new scoreboard and speaker system and upgrading the press box.[17]

The NCAA requires football programs to "average at least 15,000 in actual or paid attendance for all home football contests over a two-year rolling period" to remain at the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) level.[18] The initial expansion included 9,000 seats for the 2021 season, with plans to expand to 15,000 for the 2022 season, which will reach the FBS minimum. The expansion to 15,000 was delayed until 2023 due to effects stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced Hawaii football to play behind closed doors or with a limited capacity for the first half of their 2021 home schedule.[19]

Matlin formally announced a plan to expand to 17,000 for the 2023 season. It was presented to the University of Hawaii Board of Regents on August 17, 2022, and was unanimously approved a day later. The expansion will include a newly-expanded mauka (northern) sideline stand with additional hospitality areas, additions to both end zone stands, filled corners, and the relocation of the old Aloha Stadium HD video board to the end zone stand adjacent to Les Murakami Stadium.[20][21] As some of the new stands will be built over top of the current track, the expansion will necessitate the construction of a new facility for Hawai'i women's soccer and track, which will be built on the site of two practice fields near Murakami Stadium.

Year by year

| Season | Head Coach | Conference | Avg. Crowd | Home Record |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | Todd Graham | Mountain West Conference | 2,302 | 4-2 |

| 2022 | Timmy Chang | 9,210 | 3-4 | |

| 2023 | 11,251 | 4-3 | ||

| 2024 | - | 0-0 |

See also

- List of NCAA Division I FBS football stadiums

- Les Murakami Stadium, located to the southeast of the complex

- Stan Sheriff Center, located to the west of the complex

References

- ^ "UH Athletics Prepares to Play Football On-Campus in 2021". Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Clarence T. C. Ching Athletics Complex". hawaiiathletics.com. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "The Clarence T.C. Ching Foundation". hawaiimagazine.com. December 28, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "Wahine Experience". espnhonolulu.com. October 24, 2017. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Clarence T. C. Ching Athletics Complex Dedicated". hawaiiathletics.com. May 15, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "Clarence T. C. Ching Athletics Complex". Venues Unlimited. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "About Clarence T.C. Ching". clarencetcchingfoundation.org. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ UH sports gift pays tribute to developer. Star Bulletin (2008-05-30). Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ^ Yap, Rodney S. (2012-07-19). Ching Foundation Enables UH to Upgrade Athletics Complex. Maui Now. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ^ Briggs, Christine (2019-08-13). Clarence T.C. Ching Athletic Complex: A game changer. Play Clean. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ^ UH athletics complex opens 2 years late; cost 60% more than first estimate. Hawaii News Now (2015-05-15). Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ^ Jay talks Clarence TC Ching Athletic Complex shortcomings. Hawaii News Now (2014-05-30). Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ^ McCraken, David (2014-12-15). Size does matter . Manoa Now. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ^ a b "Clarence T. C. Ching Athletics Complex". milesplit.com. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "New events halted at Aloha Stadium over virus, budget issues". The Washington Times. AP. December 18, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Chinen, Kyle (January 11, 2021). "'Bows to play football home games on campus after Aloha Stadium fallout". hawaiinewsnow.com. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "UH Athletics Prepares to Play Football On-Campus in 2021". hawaiiathletics.com (Press release). January 11, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Bonagura, Kyle (December 17, 2020). "Hawai'i football in search of new home as Aloha Stadium closed to new events". ESPN.com. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ McInnis, Brian. "Matlin announces Ching Complex expansion to proceed, but will be delayed a year". Pacific Business Journals. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- ^ Morales, Manolo (August 17, 2022). "Matlin to present expansion plan to UH Board of Regents". KHON2. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ "Board of Regents approves two-phase, $30 million expansion project". University of Hawaii System. August 18, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- American football venues in Hawaii

- Athletics (track and field) venues in Hawaii

- College beach volleyball venues in the United States

- College cross country courses in the United States

- College track and field venues in the United States

- Cross country running courses in the United States

- Hawaii Rainbow Warriors and Rainbow Wahine

- Hawaiʻi Rainbow Wāhine beach volleyball venues

- Hawaii Rainbow Warriors football

- Hawaii Rainbow Warriors and Rainbow Wahine track and field

- Volleyball venues in Hawaii

- Sports venues completed in 2015

- 2015 establishments in Hawaii

- Baseball venues in Hawaii

- College football venues

- Defunct minor league baseball venues

- Defunct baseball venues in the United States

- High school football venues in the United States

- NCAA bowl game venues

- North American Soccer League (1968–1984) stadiums

- Rugby league stadiums in the United States

- The Hawaiians

- Tulsa Roughnecks sports facilities

- Soccer venues in Hawaii

- Sports in Honolulu

- Sports venues completed in 1975

- Buildings and structures in Honolulu

- Tourist attractions in Honolulu

- 1975 establishments in Hawaii

- Kanaloa Hawai’i