Remdesivir

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /rɛmˈdɛsɪvɪər/ rem-DESS-i-veer |

| Trade names | Veklury |

| Other names | GS-5734 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.302.974 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

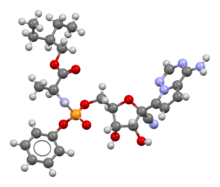

| Formula | C27H35N6O8P |

| Molar mass | 602.585 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Remdesivir, sold under the brand name Veklury,[2][3] is a broad-spectrum antiviral medication developed by the biopharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences.[4] It is administered via injection into a vein.[5][6] Remdesivir is being tested as a treatment for COVID‑19, and has been authorized for emergency use in the US, India,[7] Singapore,[8] and approved for use in Japan, the European Union, and Australia for people with severe symptoms.[2][3][9][10][11][12] It also received approval in the UK in May 2020; however, it was going to be rationed due to limited supply.[13] It may shorten the time it takes to recover from the infection.[14]

The most common side effect in healthy volunteers is raised blood levels of liver enzymes (a sign of liver problems).[2] The most common side effects in people with COVID‑19 is nausea (feeling sick).[2]

Side effects may include liver inflammation and an infusion-related reaction with nausea, low blood pressure, and sweating.[15] It is a prodrug that is intentended to allow intracellular delivery of GS-441524 monophosphate and subsequent biotransformation into GS-441524 triphosphate, a ribonucleotide analogue inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase.[16]

Earlier studies found antiviral activity against several RNA viruses including SARS coronavirus and MERS coronavirus, but it is not approved for any indication.[4][9] Remdesivir was originally developed to treat hepatitis C[17] and was then tested against Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease, but was ineffective for all of these viral infections.[4][18]

Side effects

The most common adverse effects in studies of remdesivir for COVID‑19 include respiratory failure and organ impairment, including low albumin, low potassium, low count of red blood cells, low count of platelets that help with clotting, and yellow discoloration of the skin.[19][unreliable medical source?] Other reported side effects include gastrointestinal distress, elevated transaminase levels in the blood (liver enzymes), and infusion site reactions.[6]

Other possible side effects of remdesivir include:

- Infusion‐related reactions. Infusion‐related reactions have been seen during a remdesivir infusion or around the time remdesivir was given.[20] Signs and symptoms of infusion‐related reactions may include: low blood pressure, nausea, vomiting, sweating, and shivering.[20]

- Increases in levels of liver enzymes, seen in abnormal liver blood tests.[20] Increases in levels of liver enzymes have been seen in people who have received remdesivir, which may be a sign of inflammation or damage to cells in the liver.[20]

Research

Remdesivir was originally created and developed by Gilead Sciences in 2009, as part of the company's research and development program for hepatitis C.[17] It did not work against hepatitis C as hoped,[17] but was then repurposed and studied as a potential treatment for Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus infections.[18] According to the Czech News Agency, this new line of research was carried out under the direction of scientist Tomáš Cihlář.[21] A collaboration of researchers from the CDC and Gilead Sciences subsequently discovered that remdesivir had antiviral activity in vitro against multiple filoviruses, pneumoviruses, paramyxoviruses, and coronaviruses.[22]

Preclinical and clinical research and development was done in collaboration between Gilead Sciences and various US government agencies and academic institutions.[23][24][25][26]

During the mid-2010s, the Mintz Levin law firm prosecuted various patent applications for remdesivir on behalf of Gilead Sciences before the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The USPTO granted two patents on remdesivir to Gilead Sciences on 9 April 2019: one for filoviruses,[27] and one which covered both arenaviruses and coronaviruses.[28]

Ebola

In October 2015, the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) announced preclinical results that remdesivir had blocked the Ebola virus in Rhesus monkeys. Travis Warren, who has been a USAMRIID principal investigator since 2007, said that the "work is a result of the continuing collaboration between USAMRIID and Gilead Sciences".[29] The "initial screening" of the "Gilead Sciences compound library to find molecules with promising antiviral activity" was performed by scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[29] As a result of this work, it was recommended that remdesivir "should be further developed as a potential treatment."[18][unreliable medical source?][29]

Remdesivir was rapidly pushed through clinical trials due to the West African Ebola virus epidemic of 2013–2016, eventually being used in people with the disease. Preliminary results were promising; it was used in the emergency setting during the Kivu Ebola epidemic that started in 2018, along with further clinical trials, until August 2019, when Congolese health officials announced that it was significantly less effective than monoclonal antibody treatments such as mAb114 and REGN-EB3. The trials, however, established its safety profile.[30]

COVID‑19

In January 2020, Gilead Sciences began laboratory testing of remdesivir against SARS-CoV-2, stating that remdesivir had been shown to be active against severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in animal models.[31][32][33] On 21 January 2020, the Wuhan Institute of Virology applied for a Chinese "use patent" for treating COVID‑19.[34]

In a trial in China over February–March 2020, remdesivir was not effective in reducing the time for improvement from COVID‑19 or deaths, and caused various adverse effects, requiring the investigators to terminate the trial.[19]

On 18 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the launch of a trial that would include one group treated with remdesivir.[35][36] Other clinical trials are underway or planned.[37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47]

As of April 2020[update], remdesivir was viewed as the most promising treatment for COVID‑19,[14] and was included among four treatments under evaluation in the international Solidarity trial[35][48] and European Discovery trial.[49] The FDA stated, on 1 May 2020, that it is "reasonable to believe" that known and potential benefits of remdesivir outweigh its known and potential risks in some specific populations hospitalized with severe COVID‑19.[9]

In April 2020, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) started a 'rolling review' of data on the use of remdesivir in COVID‑19.[50] It completed the review in May 2020.[51]

Preliminary data from an international multi-center, placebo controlled double-blind randomized trial carried out by the US National Institutes of Health suggests that remdesivir is effective in reducing the recovery time from 15 to 11 days in people hospitalized with COVID‑19.[52][53] On 29 April 2020, based on results of the ACTT trial,[47] the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) announced that remdesivir was better than a placebo in reducing time to recovery for people hospitalized with advanced COVID‑19 and lung involvement.[53] The study appeared on The New England Journal of Medicine website almost a month later on 22 May 2020 and, despite generally positive results, the study concluded that "given high mortality despite the use of remdesivir, it is clear that treatment with an antiviral drug alone is not likely to be sufficient."[52][54] A previous Chinese study published in The Lancet did not show significant benefits or drawbacks of using remdesivir, concluding that further research is required to understand the effectiveness of the drug.[19] John David Norrie of the Clinical Trials Unit of the University of Edinburgh Medical School criticised that article as underpowered due to a lack of significant results as well as the fact that the study was ended prematurely.[55] Based on the results of its study, the NIH stopped the ACTT trial and provided remdesivir to participants assigned to received placebo.[56]

In June 2020, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) started evaluating remdesivir for a conditional marketing authorization after receiving an application from Gilead Sciences.[57][58] On 25 June 2020, the committee recommended granting a conditional marketing authorization for remdesivir for the treatment of COVID‑19 in adults and adolescents from 12 years of age with pneumonia who require supplemental oxygen.[59][60][61] The brand name will be Veklury.[59][60]

Remdesivir was approved for medical use in the European Union in July 2020.[2] It is indicated for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) in adults and adolescents (aged 12 years and older with body weight at least 40 kg) with pneumonia requiring supplemental oxygen.[2]

A small trial of remdesivir in rhesus macaque monkeys with COVID‑19 infections reported that early treatment with remdesivir reduced damage and disease progression, but not viral shedding.[62]

According to international experts from the British Medical Journal, "the drug probably has no important effect on the need for mechanical ventilation and may have little or no effect on the length of hospital stay". Because of the high price, the authors point out that remdesivir may divert funds and efforts away from other effective treatments against COVID-19.[63]

Veterinary uses

GS-441524 was shown in 2019, to have promise for treating feline infectious peritonitis caused by a coronavirus.[64] It has not been evaluated or approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of feline coronavirus or feline infectious peritonitis but has been available since 2019, through websites and social media as an unregulated black market substance as confirmed by the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine.[65] Because GS-441524 is the main circulating metabolite of remdesivir and because GS-441524 has similar potency against SARS-Cov-2 in vitro, some researchers have argued for the direct administration of GS-441524 as a COVID19 treatment.[66]

Access

Compassionate use

On 20 March 2020, United States President Donald Trump announced that remdesivir was available for "compassionate use" for people with COVID‑19; FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn confirmed the statement at the same press conference.[67] It was later revealed that Gilead had been providing remdesivir in response to compassionate use requests since 25 January.[17] On 23 March 2020, Gilead voluntarily suspended access for compassionate use (excepting cases of critically ill children and pregnant women), for reasons related to supply, citing the need to continue to provide the agent for testing in clinical trials.[14][68]

Pricing

On 29 June 2020, Gilead announced that it had set the price of remdesivir at US$390 per vial for the governments of developed countries, including the United States, and US$520 for US private health insurance companies.[69] The expected course of treatment is six vials over five days for a total cost of US$2,340.[69] Being a repurposed drug, the minimum production cost for remdesivir is estimated at US$0.93 per day of treatment.[70]

Secondary manufacture and distribution

On 12 May 2020, Gilead announced that it had granted non-exclusive voluntary licenses to five generic drug companies in India and Pakistan to manufacture remdesivir for distribution to 127 countries.[71][72] The agreements were structured so that the licensees can set their own prices and will not have to pay royalties to Gilead until the WHO declares an end to the COVID‑19 emergency or another medicine or vaccine is approved for COVID‑19, whichever comes first.[71] On 23 June 2020, India granted emergency marketing approval of generic remdesivir manufactured by two Gilead licensees, Cipla and Hetero Drugs.[73]

Australia

In July 2020, remdesivir was provisionally approved for use in Australia for use in adults and adolescents with severe COVID‑19 symptoms who have been hospitalized.[12][74] Australia claims to have a sufficient supply of remdesivir in its national stockpile.[75]

Canada

As of 11 April 2020, access in Canada was available only through clinical trials.[76] Health Canada approved requests to treat twelve people with remdesivir under the department's special-access program (SAP).[77] Additional doses of remdesivir are not available through the SAP except for pregnant women or children with confirmed COVID‑19 and severe illness.[76]

On 19 June 2020, Health Canada received a new application to authorize remdesivir for treating COVID‑19.[76]

Czech Republic

On 17 March 2020, the drug was provisionally approved for use for COVID‑19 patients in a serious condition as a result of the outbreak in the Czech Republic.[78]

European Union

On 17 February 2016, orphan designation (EU/3/16/1615) was granted by the European Commission to Gilead Sciences International Ltd, United Kingdom, for remdesivir for the treatment of Ebola virus disease.[79]

In April 2020, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) provided recommendations on compassionate use of remdesivir for COVID‑19 in the EU.[80]

On 11 May 2020, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the EMA recommended expanding the compassionate use of remdesivir to those not on mechanical ventilation.[81] In addition to those undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation, the compassionate use recommendations cover the treatment of hospitalized individuals requiring supplemental oxygen, non-invasive ventilation, high-flow oxygen devices or ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation).[81] The updated recommendations were based on preliminary results from the NIAID-ACTT study,[47] which suggested a beneficial effect of remdesivir in the treatment of hospitalized individuals with severe COVID‑19.[81][53] In addition, a treatment duration of five days was introduced alongside the longer ten-day course, based on preliminary results from another study (GS-US-540-5773) suggesting that for those not requiring mechanical ventilation or ECMO, the treatment course may be shortened from ten to five days without any loss of efficacy.[81] Individuals who receive a five-day treatment course but do not show clinical improvement will be eligible to continue receiving remdesivir for an additional five days.[81]

On 3 July 2020, the European Union granted a conditional marketing authorization for remdesivir with an indication for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) in adults and adolescents (aged 12 years and older with body weight at least 40 kilograms [88 lb]) with pneumonia requiring supplemental oxygen.[2] At the end of July, the European Union secured a €63 million (US$74 million) contract with Gilead, to make the drug available there in early August of 2020.[82]

Japan

On 7 May 2020, Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare approved the drug for use in Japan, in a fast-tracked process based on the US emergency authorization.[3][11]

United States (and rest-of-world impact)

On 1 May 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration granted Gilead emergency use authorization (EUA) for remdesivir to be distributed and used by licensed health care providers to treat adults and children hospitalized with severe COVID‐19.[10][20] Severe COVID‐19 is defined as patients with an oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤ 94% on room air or requiring supplemental oxygen or requiring mechanical ventilation or requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), a heart–lung bypass machine.[83][20][84][85] Distribution of remdesivir under the EUA will be controlled by the US government for use consistent with the terms and conditions of the EUA.[20] Gilead will supply remdesivir to authorized distributors, or directly to a US government agency, who will distribute to hospitals and other healthcare facilities as directed by the US government, in collaboration with state and local government authorities, as needed.[20] Gilead stated they were donating 1.5 million vials for emergency use[84] and estimated, as of April 2020, they had enough remdesivir for 140,000 treatment courses and expect to have 500,000 courses by October 2020, and one million courses by the end of 2020.[86][87]

The initial distribution of the drug in the US was tripped up by seemingly capricious decision-making and finger-pointing, resulting in over a week of confusion and frustration among health care providers and patients alike.[88][89][90] On 9 May 2020, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) explained in a statement that it would be distributing remdesivir vials to state health departments, then would allow each department to redistribute vials to hospitals in their respective states based upon each department's insight into "community-level needs."[91] HHS also clarified that only 607,000 vials of Gilead's promised donation of 1.5 million vials would be going to American patients.[91] However, HHS did not explain why several states with some of the highest caseloads had been omitted from the first two distribution rounds, including California, Florida, and Pennsylvania.[91] In May 2020, Gilead indicated they would increase the number of doses donated to the US from 607,000 to around 940,000.[92][90] Some of the initial distribution was sent to the wrong hospitals, to hospitals with no intensive care units, and to facilities without the needed refrigeration to store it.[90]

On 29 June, HHS announced an unusual agreement with Gilead in which HHS agreed to Gilead's wholesale acquisition price, HHS would continue to work together with state governments and drug wholesaler AmerisourceBergen to allocate shipments of remdesivir vials to American hospitals through the end of September 2020, and in exchange, during that three-month timeframe (July, August, and September), American patients would be allocated over 90% of Gilead's projected remdesivir output of more than 500,000 treatment courses.[93][94] Absent from these announcements was any discussion of allocation of remdesivir production to the approximately 70 countries omitted from Gilead's generic drug licensing agreements—including much of Europe[95] and countries as populous as Brazil, China, and Mexico—or the 127 countries listed on those agreements (during the time it will take for Gilead's generic licensees to ramp up their own production).[96] As the implications of this began to sink in, several countries publicly confirmed the next day that they already had adequate supplies of remdesivir to cover current needs, including Australia,[97] Germany,[98] and the United Kingdom.[99]

Pharmacology

Activation

Remdesivir is a ProTide (Prodrug of nucleoTide). It is able to diffuse into cells where it is converted to GS-441524 mono-phosphate via the actions of esterases (CES1 and CTSA) and a phosphoamidase (HINT1); this in turn is further phosphorylated to its active metabolite triphosphate by nucleoside-phosphate kinases.[101][102] This pathway of bioactivation is meant to occur intracellularly, but a substantial amount of remdesivir is prematurely hydrolyzed in plasma, with GS-441524 being the major metabolite in plasma, and the only metabolite remaining two hours after dosing.[16]

Mechanism of action

As an adenosine nucleoside triphosphate analog (GS-443902),[103] the active metabolite of remdesivir interferes with the action of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and evades proofreading by viral exoribonuclease (ExoN), causing a decrease in viral RNA production.[4][104] In some viruses such as the respiratory syncytial virus it causes the RNA-dependent RNA polymerases to pause, but its predominant effect (as in Ebola) is to induce an irreversible chain termination. Unlike with many other chain terminators, this is not mediated by preventing addition of the immediately subsequent nucleotide, but is instead delayed, occurring after five additional bases have been added to the growing RNA chain.[105] For the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase of MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-1, and SARS-CoV-2 arrest of RNA synthesis occurs after incorporation of three additional nucleotides.[106][102] Hence, remdesivir is classified as a direct-acting antiviral agent that works as a delayed chain terminator.[100][102]

Pharmacokinetics

In non-human primates, the plasma half-life of the prodrug is 20 minutes, with the main metabolite being the nucleoside, GS-441524. Two hours post injection, the main metabolite GS-441524 is present at micromolar concentrations, whilst intact Remdesivir is no longer detectable. Because of this rapid extracellular conversion to the nucleoside GS-441524, some researchers have questioned whether the active nucleotide triphosphate is truly derived from Remdesivir pro-drug removal or whether it occurs by GS-441524 phosphorylation, and whether direct administration of GS-441524 would constitute a cheaper and easier to administer COVID19 drug compared to Remdesivir.[107][16] The activated nucleotide triphosphate form has sustained intracellular levels in PBMC and presumably in other cells as well.[100]

Resistance

Mutations in the mouse hepatitis virus RNA replicase that cause partial resistance to remdesivir were identified in 2018. These mutations make the viruses less effective in nature, and the researchers believe they will likely not persist where the drug is not being used.[108]

Interactions

Remdesivir is at least partially metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2C8, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4.[109][110] Blood plasma concentrations of remdesivir are expected to decrease if it is administered together with cytochrome P450 inducers such as rifampicin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, and St John's wort.[111]

On 15 June 2020, the FDA updated the fact sheets for the emergency use authorization of remdesivir to warn that using chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine with remdesivir may reduce the antiviral activity of remdesivir.[112] Coadministration of remdesivir and chloroquine phosphate or hydroxychloroquine sulfate is not recommended based on in vitro data demonstrating an antagonistic effect of chloroquine on the intracellular metabolic activation and antiviral activity of remdesivir.[110]

Synthesis

Remdesivir can be synthesized in multiple steps from ribose derivatives. The figure to the right is one of the synthesis routes of remdesivir invented by Chun and coauthors from Gilead Sciences.[113][114] In this method, intermediate a is firstly prepared from L-alanine and phenyl phosphorodichloridate in presence of triethylamine and dichloromethane; triple benzyl-protected ribose is oxidized by dimethyl sulfoxide with acetic anhydride and give the lactone intermediate b; pyrrolo[2,1-f] [1,2,4]triazin-4-amine is brominated, and the amine group is protected by excess trimethylsilyl chloride. n-Butyllithium undergoes a halogen-lithium exchange reaction with the bromide at −78 °C (−108 °F) to yield the intermediate c. The intermediate b is then added to a solution containing intermediate c dropwise. After quenching the reaction in a weakly acidic aqueous solution, a mixture of 1: 1 anomers was obtained. It was then reacted with an excess of trimethylsilyl cyanide in dichloromethane at −78 °C (−108 °F) for 10 minutes. Trimethylsilyl triflate was added and reacts for one additional hour, and the mixture was quenched in an aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate. A nitrile intermediate was obtained. The protective group, benzyl, was then removed with boron trichloride in dichloromethane at −20 °C (−4 °F). The excess of boron trichloride was quenched in a mixture of potassium carbonate and methanol. A benzyl-free intermediate was obtained. The isomers were then separated via reversed-phase HPLC. The optically pure compound and intermediate a are reacted with trimethyl phosphate and methylimidazole to obtain a diastereomer mixture of remdesivir. In the end, optically pure remdesivir can be obtained through chiral resolution methods.[citation needed]

Manufacturing and distribution

Remdesivir requires "70 raw materials, reagents, and catalysts" to make, and approximately "25 chemical steps."[115] Some of the ingredients are extremely dangerous to humans, especially trimethylsilyl cyanide.[115] The original end-to-end manufacturing process required 9 to 12 months to go from raw materials at contract manufacturers to finished product, but after restarting production in January, Gilead Sciences was able to find ways to reduce the production time to six months.[115]

In January 2020, Gilead began working on restarting remdesivir production in glass-lined steel chemical reactors at its manufacturing plant in Edmonton, Alberta.[115] On 2 February 2020, the company flew its entire stock of remdesivir, 100 kilograms in powder form (left over from Ebola research), to its filling plant in La Verne, California to start filling vials.[115] The Edmonton plant finished its first new batch of remdesivir in April 2020.[115] Around the same time, fresh raw materials began to arrive from contract manufacturers reactivated by Gilead in January.[115]

Another challenge is getting remdesivir into patients despite the drug's "poor predicted solubility and poor stability."[116] In June 2020, Ligand Pharmaceuticals revealed that Gilead has been managing those issues by mixing Ligand's proprietary excipient Captisol (based on University of Kansas research into cyclodextrin) with remdesivir at a 30:1 ratio.[116] Since that implies an enormous amount of Captisol is needed to stabilize and deliver remdesivir (on top of amounts needed for several other drugs for which the excipient is already in regular use), Ligand announced that it is trying to boost Captisol annual manufacturing capacity to as much as 500 metric tons.[116]

Terminology

Remdesivir is the international nonproprietary name (INN)[117] while the development code name was GS-5734.[118]

Research

COVID‑19

In May 2020, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) started the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial 2 (ACTT 2) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a treatment regimen consisting of remdesivir plus baricitinib for treating hospitalized adults who have a laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection with evidence of lung involvement, including a need for supplemental oxygen, abnormal chest X-rays, or illness requiring mechanical ventilation.[119][120][121]

In August 2020, the NIAID started the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial 3 (ACTT 3) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a treatment regimen consisting of remdesivir plus interferon beta-1a for hospitalized adults who have a laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection with evidence of lung involvement, including a need for supplemental oxygen, abnormal chest X-rays, or illness requiring mechanical ventilation.[120][122]

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Veklury EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 23 June 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c "Gilead Announces Approval of Veklury (remdesivir) in Japan for Patients With Severe COVID-19" (Press release). Gilead Sciences. 7 May 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020 – via Business Wire.

- ^ a b c d Scavone C, Brusco S, Bertini M, Sportiello L, Rafaniello C, Zoccoli A, et al. (April 2020). "Current pharmacological treatments for COVID-19: What's next?". British Journal of Pharmacology. doi:10.1111/bph.15072. eISSN 1476-5381. PMC 7264618. PMID 32329520.

- ^ "Remdesivir". Drugs.com. 20 April 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Mehta N, Mazer-Amirshahi M, Alkindi N, Pourmand A (July 2020). "Pharmacotherapy in COVID-19; A narrative review for emergency providers". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 38 (7): 1488–1493. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.035. eISSN 0735-6757. PMC 7158837. PMID 32336586.

- ^ "India approves emergency use of remdesivir to treat Covid-19 patients". The Times of India. Gurgaon, Haryana, India: Times Internet. Reuters. 2 June 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Singapore approves remdesivir drug for emergency COVID-19 treatment". Reuters. 10 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Remdesivir EUA Letter of Authorization" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Issues Emergency Use Authorization for Potential COVID-19 Treatment" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Japan approves remdesivir for COVID-19 despite uncertainties". The Asahi Shimbun. 8 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Australia's first COVID treatment approved". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) (Press release). 10 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Michelle (26 May 2020). "Anti-viral drug that speeds recovery offered by NHS". BBC News Online. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Coronavirus COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2)". Johns Hopkins ABX Guide. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

Remdesivir: Likely the most promising drug.

- ^ "Fact Sheet for Patients And Parent/Caregivers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) Of Remdesivir For Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Yan, Victoria C.; Muller, Florian L. (14 May 2020). "Gilead should ditch remdesivir and focus on its simpler and safer ancestor". Stat. Boston Globe Media Partners.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Stephens, Bret (18 April 2020). "The Story of Remdesivir". The New York Times. p. A23. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Warren TK, Jordan R, Lo MK, Ray AS, Mackman RL, Soloveva V, et al. (March 2016). "Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys". Nature. 531 (7594): 381–5. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..381W. doi:10.1038/nature17180. PMC 5551389. PMID 26934220.

- ^ a b c Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y, et al. (May 2020). "Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial". Lancet. 395 (10236): 1569–1578. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. PMC 7190303. PMID 32423584.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Frequently Asked Questions on the Emergency Use Authorization for Remdesivir for Certain Hospitalized COVID‐19 Patients" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Czech News Agency, "Did Czech scientists create the cure for coronavirus?", Aktuálně.cz, 5 February 2020.

- ^ Lo MK, Jordan R, Arvey A, Sudhamsu J, Shrivastava-Ranjan P, Hotard AL, et al. (March 2017). "GS-5734 and its parent nucleoside analog inhibit Filo-, Pneumo-, and Paramyxoviruses". Scientific Reports. 7: 43395. Bibcode:2017NatSR...743395L. doi:10.1038/srep43395. PMC 5338263. PMID 28262699.

- ^ Eastman RT, Roth JS, Brimacombe KR, Simeonov A, Shen M, Patnaik S, Hall MD (May 2020). "Remdesivir: A Review of Its Discovery and Development Leading to Emergency Use Authorization for Treatment of COVID-19". ACS Central Science. 6 (5): 672–683. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.0c00489. PMC 7202249. PMID 32483554.

- ^ Silverman, Ed (8 May 2020). "U.S. government contributed research to a Gilead remdesivir patent – but didn't get credit". Stat. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Ardizzone, Kathryn (20 March 2020). "Role of the Federal Government in the Development of Remdesivir" (PDF). Knowledge Ecology International. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Investigational compound remdesivir, developed by UAB and NIH researchers, being used for treatment of novel coronavirus". UAB News. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ US 10251898, Chun BK, Clarke MO, Doerffler E, Hui HC, Jordan R, Mackman RL, Parrish JP, Ray AS, Siegel D, "Methods for treating Filoviridae virus infections", published 1 November 2018, issued 9 April 2019, assigned to Gilead Sciences, Inc.

- ^ US 10251904, Clarke MO, Feng JY, Jordan R, Mackman RL, Ray AS, Siegel D, "Methods for treating arenaviridae and coronaviridae virus infections", published 16 March 2017, issued 9 April 2019, assigned to Gilead Sciences, Inc.

- ^ a b c Antiviral Compound Provides Full Protection from Ebola Virus in Nonhuman Primates (PDF) (Report). San Diego, California: United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). 9 October 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Cao YC, Deng QX, Dai SX (April 2020). "Remdesivir for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 causing COVID-19: An evaluation of the evidence". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 35: 101647. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101647. PMC 7151266. PMID 32247927.

- ^ de Wit E, Feldmann F, Cronin J, Jordan R, Okumura A, Thomas T, et al. (March 2020). "Prophylactic and therapeutic remdesivir (GS-5734) treatment in the rhesus macaque model of MERS-CoV infection". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (12): 6771–6776. doi:10.1073/pnas.1922083117. PMC 7104368. PMID 32054787.

- ^ Sheahan TP, Sims AC, Graham RL, Menachery VD, Gralinski LE, Case JB, et al. (June 2017). "Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses". Science Translational Medicine. 9 (396): eaal3653. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653. PMC 5567817. PMID 28659436.

- ^ Joseph, Saumya Sibi; Samuel, Maju (31 January 2020). "Gilead working with China to test Ebola drug as new coronavirus treatment". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Barmann, Jay (6 February 2020). "Bay Area-Based Gilead Sees Potential Legal Conflict With China Over Its Coronavirus Drug". SFist. Impress Media. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b ""Solidarity" clinical trial for COVID-19 treatments". World Health Organization (WHO). 3 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "UN health chief announces global 'solidarity trial' to jumpstart search for COVID-19 treatment". UN News. 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Remdesivir Clinical Trials". Gilead Sciences. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "7 Studies found for: Remdesivir & Recruiting, Not yet recruiting, Active, not recruiting, Completed, Enrolling by invitation Studies & COVID-19". ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "A Trial of Remdesivir in Adults With Severe COVID-19". ClinicalTrials.gov. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "A Trial of Remdesivir in Adults With Mild and Moderate COVID-19". ClinicalTrials.gov. 5 February 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Study to Evaluate the Safety and Antiviral Activity of Remdesivir (GS-5734) in Participants With Moderate Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Compared to Standard of Care Treatment". ClinicalTrials.gov. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Study to Evaluate the Safety and Antiviral Activity of Remdesivir (GS-5734) in Participants With Severe Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". ClinicalTrials.gov. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Trial of Treatments for COVID-19 in Hospitalized Adults (DisCoVeRy)". ClinicalTrials.gov. 20 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Expanded Access Remdesivir (RDV; GS-5734)". ClinicalTrials.gov. 10 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Expanded Access Treatment Protocol: Remdesivir (RDV; GS-5734) for the Treatment of SARS-CoV2 (CoV) Infection (COVID-19)". ClinicalTrials.gov. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Multi-centre, adaptive, randomized trial of the safety and efficacy of treatments of COVID-19 in hospitalized adults (DisCoVeRy)". European Union Clinical Trials Register. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT)". ClinicalTrials.gov. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Kupferschmidt, Kai; Cohen, Jon (22 March 2020). "WHO launches global megatrial of the four most promising coronavirus treatments". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb8497.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Launch of a European clinical trial against COVID-19". INSERM. 22 March 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "EMA starts rolling review of remdesivir for COVID-19". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 30 April 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Treatments and vaccines for COVID-19". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 11 April 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ a b Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, et al. (May 2020). "Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Preliminary Report". The New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. PMC 7262788. PMID 32445440.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "NIH Clinical Trial Shows Remdesivir Accelerates Recovery from Advanced COVID-19" (Press release). National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Kolata, Gina (23 May 2020). "Federal Scientists Finally Publish Remdesivir Data". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Norrie, John David (May 2020). "Remdesivir for COVID-19: challenges of underpowered studies". Lancet. 395 (10236): 1525–1527. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31023-0. PMC 7190306. PMID 32423580.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Herper, Matthew (11 May 2020). "Inside the NIH's controversial decision to stop its big remdesivir study". Stat. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "EMA receives application for conditional authorisation of first COVID-19 treatment in the EU" (Press release). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 8 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Treatments and vaccines for COVID-19". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 11 April 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "First COVID-19 treatment recommended for EU authorisation" (Press release). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 25 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Veklury: Pending EC decision". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 25 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Veklury product information" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ Williamson BN, Feldmann F, Schwarz B, Meade-White K, Porter DP, Schulz J, et al. (June 2020). "Clinical benefit of remdesivir in rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2". Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2423-5. PMID 32516797.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) - ^ Wilson J. (July 30, 2020). "Remdesivir Gets Lukewarm Endorsement From Experts in Covid Fight". Bloomberg. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Pedersen NC, Perron M, Bannasch M, Montgomery E, Murakami E, Liepnieks M, et al. (April 2019). "Efficacy and safety of the nucleoside analog GS-441524 for treatment of cats with naturally occurring feline infectious peritonitis". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 21 (4): 271–281. doi:10.1177/1098612X19825701. PMC 6435921. PMID 30755068.

- ^ Pedersen, Niels C. (18 June 2019). "Black market production and sale of GS-441524 and GC376" (PDF). Davis, California: Feline Infectious Peritonitis Therapeutics/Clinical Trials Team, UC Davis. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Westgate, James (7 May 2020). "Vet science 'being ignored' in quest for COVID-19 drug". vettimes.co.uk.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Naftulin, Julia (20 March 2020). "The FDA is allowing two drugs to be used for 'compassionate use' to treat the coronavirus. Here's what that means". Business Insider. New York City: Springer.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Cerullo, Megan (23 March 2020). "Gilead suspends emergency access to experimental coronavirus drug remdesivir". CBS News. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "An Open Letter from Daniel O'Day, Chairman & CEO, Gilead Sciences" (Press release). Gilead Sciences. 29 June 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Hill A, Wang J, Levi J, Heath K, Fortunak J (April 2020). "Minimum costs to manufacture new treatments for COVID-19". Journal of Virus Eradication. 6 (2): 61–69. doi:10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30018-2. PMC 7213074. PMID 32405423.

- ^ a b Silverman, Ed (12 May 2020). "Gilead signs deals for generic companies to make and sell remdesivir". Stat. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "India, Pakistan to make drug to 'fight coronavirus'". BBC News Online. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Rajagopal, Divya (23 June 2020). "Cipla, Hetero receive drug controller's emergency approval for Remdesivir for severe Covid-19 patients". The Economic Times. Mumbai, India: Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Remdesivir approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration for severe coronavirus cases". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 11 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Hitch, Georgia (1 July 2020). "Australia has enough coronavirus drug remdesivir thanks to early supply donation, Health Minister says". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): For health professionals". Public Health Agency of Canada. 11 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

Gilead is transitioning the provision of emergency access to remdesivir from individual compassionate use via Health Canada's Special Access Program requests to access through clinical trials.

- ^ Blackwell, Tom (1 May 2020). "Canadian experts don't see Remdesivir as a COVID-19 killer: 'This is not a silver bullet'". National Post. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Opatření MZ ČR – povolení LP Remdesivir" [Measures of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic – LP Remdesivir permit] (PDF). www.mzcr.cz (in Czech). 17 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020. HTML Version

- ^ "EU/3/16/1615". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 7 July 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "EMA provides recommendations on compassionate use of remdesivir for COVID-19". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 3 April 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "EMA recommends expanding remdesivir compassionate use to patients not on mechanical ventilation". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 11 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Guarascio, Francesco (29 July 2020). "EU buys remdesivir to treat 30,000 COVID patients, seeks more". Reuters. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "FDA EUA Remdesivir Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "U.S. Emergency Approval Broadens Use of Gilead's COVID-19 Drug Remdesivir". The New York Times. Reuters. 1 May 2020. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Holland, Steve; Beasley, Deena (4 May 2020). "U.S. emergency approval broadens use of Gilead's COVID-19 drug remdesivir". Reuters. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Jarvis, Lisa M. (20 April 2020). "Scaling up remdesivir amid the coronavirus crisis". Chemical and Engineering News.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Rowland, Christopher (10 April 2020). "Gilead's experimental drug remdesivir shows 'hopeful' signs in small group of coronavirus patients". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Kolata, Gina (8 May 2020). "Haphazard Rollout of Coronavirus Drug Frustrates Doctors". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Swan, Jonathan (8 May 2020). "Scoop: Trump officials' dysfunction harms delivery of coronavirus drug". Axios. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Abutaleb, Yasmeen; Dawsey, Josh; Sun, Lena H.; McGinley, Laurie (28 May 2020). "Administration initially dispensed scarce covid-19 drug to some hospitals that didn't need it". The Washington Post. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Facher, Lev (9 May 2020). "Trump administration announces plan to distribute Covid-19 drug amid concerns over allocation". Stat. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston Globe Media. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Branswell, Helen (19 May 2020). "Gilead ups its donation of the Covid-19 drug remdesivir". Stat. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston Globe Media Partners. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)} - ^ Kolata, Gina (29 June 2020). "Remdesivir, the First Coronavirus Drug, Gets a Price Tag". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Trump Administration Secures New Supplies of Remdesivir for the United States" (Press release). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 29 June 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Boseley, Sarah (30 June 2020). "US buys up world stock of key Covid-19 drug". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Baragona, Steve (29 June 2020). "US Procures Almost Entire Supply of COVID-19 Drug". Voice of America. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Agency for Global Media. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Davey, Melissa (1 July 2020). "Gilead donates Covid-19 drug remdesivir to Australia's medical stockpile after US buys up supply". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Rinke, Andreas (1 July 2020). "Germany has for now enough remdesivir for COVID-19 therapy: govt". Reuters. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Stout, Alistair; Mason, Josephine (1 July 2020). "UK emergency remdesivir supplies adequate to treat COVID-19, official says". Reuters.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Eastman RT, Roth JS, Brimacombe KR, Simeonov A, Shen M, Patnaik S, Hall MD (May 2020). "Remdesivir: A Review of Its Discovery and Development Leading to Emergency Use Authorization for Treatment of COVID-19". ACS Central Science. 6 (5): 672–683. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.0c00489. PMC 7202249. PMID 32483554.

- ^ Sheahan TP, Sims AC, Graham RL, Menachery VD, Gralinski LE, Case JB, et al. (June 2017). "Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses". Science Translational Medicine. 9 (396): eaal3653. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653. PMC 5567817. PMID 28659436.

- ^ a b c Gordon CJ, Tchesnokov EP, Woolner E, Perry JK, Feng JY, Porter DP, Götte M (May 2020). "Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 295 (20): 6785–6797. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA120.013679. PMC 7242698. PMID 32284326.

- ^ Cho A, Saunders OL, Butler T, Zhang L, Xu J, Vela JE, et al. (April 2012). "Synthesis and antiviral activity of a series of 1'-substituted 4-aza-7,9-dideazaadenosine C-nucleosides". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 22 (8): 2705–7. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.105. PMC 7126871. PMID 22446091.

- ^ Ferner RE, Aronson JK (April 2020). "Remdesivir in covid-19". BMJ. 369: m1610. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1610. PMID 32321732.

- ^ Tchesnokov EP, Feng JY, Porter DP, Götte M (April 2019). "Mechanism of Inhibition of Ebola Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase by Remdesivir". Viruses. 11 (4): 326. doi:10.3390/v11040326. PMC 6520719. PMID 30987343.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Gordon CJ, Tchesnokov EP, Feng JY, Porter DP, Götte M (April 2020). "The antiviral compound remdesivir potently inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 295 (15): 4773–4779. doi:10.1074/jbc.AC120.013056. PMC 7152756. PMID 32094225.

- ^ Yan, Victoria C.; Muller, Florian L. (July 2020). "Advantages of the parent nucleoside GS-441524 over remdesivir for Covid-19 treatment". ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 11 (7): 1361–1366. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00316. PMC 7315846. PMID 32665809. S2CID 220056568.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Chiotos K, Hayes M, Kimberlin DW, Jones SB, James SH, Pinninti SG, et al. (April 2020). "Multicenter initial guidance on use of antivirals for children with COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2". Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society: piaa045. doi:10.1093/jpids/piaa045. PMC 7188128. PMID 32318706.

- ^ "Summary on Compassionate Use: Remdesivir Gilead" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 3 April 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Fact Sheet For Health Care Providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) Of Remdesivir (GS-5734TM)" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 15 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "COVID-19 interactions". University of Liverpool. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Warns of Newly Discovered Potential Drug Interaction That May Reduce Effectiveness of a COVID-19 Treatment Authorized for Emergency Use" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 15 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ US 9724360, Chun BK, Clarke MO, Doerffler E, Hui HC, Jordan R, Mackman RL, Parrish JP, Ray AS, Siegel D, "Methods for treating Filoviridae virus infections", published 5 May 2016, issued 8 August 2017, assigned to Gilead Sciences Inc.

- ^ WO 2017184668, Clarke MO, Jordan R, Mackman RL, Ray AS, Siegel D, "Preparation of amino acid-containing nucleosides for treating flaviviridae virus infections", published 26 October 2017, assigned to Glead Sciences Inc

- ^ a b c d e f g Langreth, Robert (14 May 2020). "All Eyes on Gilead". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Pipkin, James; Antle, Vince; Garcia-Fandiño, Rebeca (June 2020). "FORMULATION FORUM – Application of Captisol® Technology to Enable the Formulation of Remdesivir in Treating COVID-19". Drug Development & Delivery. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ World Health Organization (2017). "International nonproprietary names for pharmaceutical substances (INN): recommended INN: list 78". WHO Drug Information. 31 (3): 549. hdl:10665/330961.

- ^ "Pipeline". Gilead Sciences. 27 February 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "NIH Clinical Trial Testing Antiviral Remdesivir Plus Anti-Inflammatory Drug Baricitinib for COVID-19 Begins". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (Press release). 8 May 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "NIH Clinical Trial Testing Remdesivir Plus Interferon Beta-1a for COVID-19 Treatment Begins". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (Press release). 30 July 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial 2 (ACTT-2)". ClinicalTrials.gov. 26 May 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial 3 (ACTT-3)". ClinicalTrials.gov. 30 July 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

Further reading

- Kolata, Gina (1 May 2020). "How Remdesivir, New Hope for Covid-19 Patients, Was Resurrected". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - "Remdesivir Clinical Data". Gilead Sciences.

External links

- "Remdesivir". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Gilead Sciences Update On The Company's Ongoing Response To COVID-19". Gilead Sciences.