Tribes of Arabia

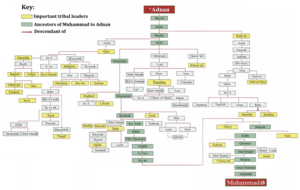

The tribes of Arabia (Arabic: قبائل الجزيرة العربية) or Arab tribes (القبائل العربية) denote Arab tribes originating in the Arabian Peninsula, who according to tradition trace their ancestry to one of the two Arab forefathers, Adnan or Qahtan.[1]

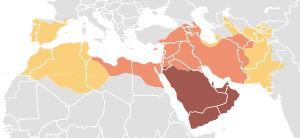

Historically, Arab tribes have inhabited the Arabian Peninsula. However, with the spread of Islam, they started migrating and settling in various regions, including the Levant,[2] Mesopotamia,[3] Egypt,[4] Sudan,[5] the Maghreb,[6] and Khuzestan.[7]

These areas collectively form what is known as the Arab world, excluding Khuzestan. Arab tribes have significantly influenced demographic shifts in this region, leading to the growth of the Arab population.[8] Additionally, they have played a vital role in the ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and genetic Arabization of the Levant and North Africa.[9]

Arab genealogical tradition

[edit]The general consensus among 14th-century Arab genealogists is that Arabs are of three kinds:

- Al-Arab al-Ba'ida (Arabic: العرب البائدة), "The Extinct Arabs", were an ancient group of tribes in pre-Islamic Arabia that included the ‘Ād, the Thamud, the Tasm and the Jadis, thelaq (who included branches of Banu al-Samayda), and others. The Jadis and the Tasm are said to have been exterminated by genocide.[10] The Quran says that the disappearance of the 'Ad and Thamud came about due to their decadence. Recent archaeological excavations have uncovered inscriptions that reference 'Iram, once a major city of the 'Aad.

- Al-Arab al-Ariba (Arabic: العرب العاربة), "The Pure Arabs", came from Qahtanite Arabs.[11][12]

- Al-Arab al-Mustarabah (Arabic: العرب المستعربة), “The Arabized Arabs”, also known as the Adnanite Arabs, were the progeny of Ismail, the firstborn son of the patriarch Abraham.

The Hawazin tribe and the Quraysh tribe are considered ‘Adnani Arabs. Much of the lineage provided before Ma'ad relies on biblical genealogy, so questions persist concerning the accuracy of this segment of Adnanite Arab genealogy.[13] Adnanites are believed to be the descendants of Ishmael through Adnan but the traditional Adnanite lineage does not match the biblical line exactly. According to Arab tradition, the Adnanites are called Arabised because it is believed that Ishmael spoke Aramaic and Egyptian then learnt Arabic from a Qahtanite Yemeni woman that he married. Therefore, the Adnanites are descendants of Abraham. Modern historiography "unveiled the lack of inner coherence of this genealogical system and demonstrated that it finds insufficient matching evidence".[14]

Pre-Islamic History

[edit]The tribes of Arabia were engaged in nomadic herding and agriculture by around 6,000 BCE. By about 1,200 BCE, a complex network of settlements and camps was established. Kingdoms in the southern region of Arabia began to form and flourish. The earliest Arab tribes emerged from Bedouins.[15] A major source of income for these people was the taxation of caravans, as well as tributes collected from non-Bedouin settlements. They also earned income by transporting goods and people in caravans pulled by domesticated camels across the desert.[16] Scarcity of water and of permanent pastoral land required them to move constantly.[citation needed]

The Nabataeans and Qedarites were Arabian tribes on the edges of the fertile Crescent who expanded into the Southern Levant by the 5th century BCE, causing the displacement of Edomites. Their inscriptions were in predominantly in Aramaic, but it's assumed their native spoken language was a variant of Old Arabic, one of many Ancient North Arabian languages, which is attested in inscriptions as early as the 1st century [citation needed], the same period in which the Nabataean alphabet slowly evolved into the Arabic script by the 6th century.[citation needed] This is attested by Safaitic inscriptions (beginning in the 1st century BCE) and the many Arabic personal names in other Nabataean inscriptions. From about the 2nd century BCE, a few inscriptions from Qaryat al-Faw reveal a dialect no longer considered proto-Arabic, but pre-classical Arabic. Five Syriac inscriptions mentioning Arabs have been found at Sumatar Harabesi, one of which dates to the 2nd century CE.[citation needed]

The Ghassanids, Lakhmids and Kindites were the last major migration of pre-Islamic Arabs out of Yemen to the north. The Ghassanids increased the Arabian presence in the Syria, They mainly settled in the Hauran region and spread to modern-day Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and Jordan.[citation needed]

Around the 4th century CE, there developed a dominant Jewish presence in pre-Islamic Arabia, with many Jewish Clans and tribes settling around the Red Sea coast. At the mid to the end of the fourth century, the Himyarite Kingdom adopted Judaism, thus spreading Judaism in the region even further. The German Orientalist Ferdinand Wüstenfeld believed that the Jews established a state in northern Hejaz.[17] The Quran details early encounters between early Muslim tribes and Jewish tribes in major cities in western Arabia, with some clans like Banu Qurayza and Banu Nadir being described as having a seat of power in the region.

Medieval Migrations

[edit]Following the early Muslim conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries, the tribes of Arabia begun migrating beyond the Arabian Peninsula in large numbers into different lands and regions across the Middle and North Africa.

Middle East

[edit]Migration to the Levant

[edit]On the eve of the Rashidun Caliphate's conquest of the Levant, 634 AD, Syria's population mainly spoke Aramaic; Greek was the official language of administration.[citation needed] Arabization and Islamization of Syria began in the 7th century, and it took several centuries for Islam, the Arab identity, and language to spread;[18] the Arabs of the caliphate did not attempt to spread their language or religion in the early periods of the conquest, and formed an isolated aristocracy.[19] The Arabs of the caliphate accommodated many new tribes in isolated areas to avoid conflict with the locals; caliph Uthman ordered his governor, Muawiyah I, to settle the new tribes away from the original population.[20] Syrians who belonged to Monophysitic denominations welcomed the peninsular Arabs as liberators.[21]

Migration to Mesopotamia

[edit]The migration of Arab tribes to Mesopotamia began in the seventh century, and by the late 20th century constituted about three quarters of the population of Iraq.[22] A large Arab migration to Mesopotamia followed the Muslim conquest of Mesopotamia in 634, which saw an increase in the culture and ideals of the Bedouins in the region.[23] The second Arab tribal migration to northern Mesopotamia was in the 10th century when the Banu Numayr migrated there.[24]

Migration to Persia

[edit]After the Arab conquest of Persia in the 7th century, many Arab tribes settled in different parts of Iran, notably Khorasan and Ahwaz, it is the Arab tribes of Khuzestan that have retained their identity in language and culture to the present day while other Arabs especially in Khorasan were slowly Persianised. Khorasani Arabs were mainly contingent from Nejdi tribes such as Banu Tamim.

There was a great influx of Arab tribes into Khuzestan from the 16th to the 19th century, including the migration of the Banu Ka'b and Banu Lam from the Arabian desert.[25][26] Tribalism is a significant characteristic of Arab population in Khuzestan.[27]

Subsequent Arab migrations into Iran, primarily across the Gulf, involved movements of Arabs from eastern Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States into the Hormozgan and Fars provinces after the 16th century. These include Sunni Huwala and Achomi people, who compromise of both fully Arab and mixed Arab-Persian families. The Arabs on the Iranian side of the Gulf tend to speak a dialect much closer to Gulf Arabic opposed to the Khuzestani Arabic which is closer to Iraqi Arabic.

North Africa

[edit]Migration to Egypt

[edit]

Ancient Bedouins and nomadic groups inhabited the Sinai Peninsula,[28] located in Asia, ever since ancient times. Prior to the Muslim conquest of Egypt, Egypt was under Greek and Roman influence. Under the Umayyad Caliphate, Arabic became the official language in Egypt rather than Coptic or Greek. The caliphate also allowed the migration of Arab tribes to Egypt.[29] The Muslim governor of Egypt encouraged the migration of tribes from the Arabian Peninsula to Egypt to strengthen his regime by enlisting warrior tribesmen to his forces, encouraging them to bring their families and entire clans.[citation needed] The Fatimid era was the peak of Bedouin Arab tribal migrations to Egypt.[30]

Migration to the Maghreb

[edit]The first wave of Arab immigration to the Maghreb began with the conquest of the Maghreb in the 7th century, with the migration of sedentary and nomadic Arabs to the Maghreb from the Arabian Peninsula.[31] Arab tribes such as Banu Muzaina migrated, and the Arab Muslims in the region had more impact on the culture of the Maghreb than the region's conquerors before and after them.[32] The major migration to the region by Arab tribes was in the 11th century when the tribes of Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym, along with others, were sent by the Fatimids to defeat a Berber rebellion and then settle in the Maghreb.[32] These tribes advanced in large numbers all the way to Morocco, contributing to a more extensive ethnic, genetic, cultural, and linguistic Arabization in the region.[33] The Arab tribes of Maqil migrated to the Maghreb a century later and even immigrated southwards to Mauritania. Beni Hassan defeated both Berbers and Black Africans in the region, pushing them southwards to the Senegal river while the Arab tribes settled in Mauritania.[34] The Arab descendants of the original Arabian settlers who continue to speak Arabic as a first language currently form the single largest population group in North Africa.[35]

Migration to Sudan

[edit]In the 12th century, the Arab Ja'alin tribe migrated into Nubia and Sudan and formerly occupied the country on both banks of the Nile from Khartoum to Abu Hamad. They trace their lineage to Abbas, uncle of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. They are of Arab origin, but now of mixed blood mostly with Nilo-Saharans and Nubians.[36][37] Other Arab tribes migrated into Sudan in the 12th century and intermarried with the indigenous populations, forming the Sudanese Arabs.[5] In 1846, many Arab Rashaida migrated from Hejaz in present-day Saudi Arabia into what is now Eritrea and north-east Sudan after tribal warfare had broken out in their homeland. The Rashaida of Sudan and Eritrea live in close proximity with the Beja people. Large numbers of Bani Rasheed are also found on the Arabian Peninsula. They are related to the Banu Abs tribe.[38]

The Great Skulls of Arabia

[edit]According to Arab traditions, tribes are divided into different divisions called Arab skulls (جماجم العرب), which is a term given to a group of tribes of the Arabian Peninsula, which are described in the traditional custom of strength, abundance, victory, and honor. A number of them branched out, which later became independent tribes (sub-tribes). They are called "Skulls" because it is thought that the skull is the most important part of the body, and the majority of Arab tribes are descended from these major tribes.[39][40][41][42][43]

They are:[41]

- Bakr, has descendants in Arabia and Iraq.[44]

- Kinanah, has descendants in Arabia, Iraq, Egypt, Sudan, Palestine, Tunisia, Morocco, and Syria and Yemen.[45]

- Hawazin, has descendants in Arabia, Libya, Algeria, Morocco, Sudan, and Iraq.[46][47][48]

- Tamim, has descendants in Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Palestine, Algeria, and Morocco[49]

- Azd, has descendants in Arabia, Iraq, Levant, and North Africa.[50]

- Ghatafan, has descendants in Arabia and the Maghreb.[51]

- Madhhij, has descendants in Arabia, Syria and Iraq.[52][53]

- Abd al-Qays, has descendants in Arabia.

- Al Qays, has descendants in Arabia, Syria and Iraq.[52][53]

- Quda'a, has descendants in Arabia, Syria, and North Africa.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Retso, Jan (2013-07-04). The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-136-87282-2. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Bierwirth, Henry Christian (1994). Like Fish in the Sea: The Lebanese Diaspora in Côte D'Ivoire, Ca. 1925-1990. University of Wisconsin--Madison. p. 42. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Lane-Pool, Stanley (2014-06-23). Mohammadan Dyn:Orientalism V 2. Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-317-85394-7. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ al-Sharkawi, Muhammad (2016-11-25). History and Development of the Arabic Language. Taylor & Francis. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-317-58864-1. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ a b Inc, IBP (2017-06-15). Sudan (Republic of Sudan) Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. Lulu.com. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4387-8540-0. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ O'Connell, Monique; Dursteler, Eric R. (2016-05-23). The Mediterranean World: From the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Napoleon. JHU Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4214-1901-5. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Arjomand, Saïd Amir (2014-05-19). Social Theory and Regional Studies in the Global Age. SUNY Press. p. 411. ISBN 978-1-4384-5161-9. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Jenkins, Everett Jr. (2015-05-07). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 1, 570-1500): A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. McFarland. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-4766-0888-4. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Nebel, Almut (June 2002). "Genetic Evidence for the Expansion of Arabian Tribes into the Southern Levant and North Africa". American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (6): 1594–1596. doi:10.1086/340669. PMC 379148. PMID 11992266.

- ^ ?abar? (1987-01-01). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 4: The Ancient Kingdoms. SUNY Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-88706-181-3. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Reuven Firestone (1990). Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis. SUNY Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780791403310. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03. Retrieved 2016-01-07.

- ^ Göran Larsson (2003). Ibn García's Shuʻūbiyya Letter: Ethnic and Theological Tensions in Medieval al-Andalus. BRILL. p. 170. ISBN 9004127402. Archived from the original on 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ^ in general: W. Caskel, Ġamharat an-Nasab, das genealogische Werk des Hišām Ibn Muḥammad al-Kalbī, Leiden 1966.

- ^ Parolin, Gianluca P. (2009). Citizenship in the Arab World: Kin, Religion and Nation-State. Amsterdam University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-9089640451. "The ‘arabicised or arabicising Arabs’, on the contrary, are believed to be the descendants of Ishmael through Adnan, but in this case the genealogy does not match the Biblical line exactly. The label ‘arabicised’ is due to the belief that Ishmael spoke Aramaic and Egyptian until he married a Yemeni woman and learnt Arabic. Both genealogical lines go back to Sem, son of Noah, but only Adnanites can claim Abraham as their ascendant, and the lineage of Mohammed, the Seal of Prophets (khatim al-anbiya'), can therefore be traced back to Abraham. Contemporary historiography unveiled the lack of inner coherence of this genealogical system and demonstrated that it finds insufficient matching evidence; the distinction between Qahtanites and Adnanites is even believed to be a product of the Umayyad Age, when the war of factions (al-niza al-hizbi) was raging in the young Islamic Empire."

- ^ Chatty, Dawn (2009). Culture Summary: Bedouin. Archived from the original on 2020-04-17. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Beckerleg, Susan. "Hidden History, Secret Present: The Origins and Status of African Palestinians". London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-05-19. Retrieved 2022-08-21. Translated by Salah Al Zaroo.

- ^ Wolfensohn, Israel. "Tarikh Al-Yahood Fi Belad Al-Arab". Al-Nafezah Publication. Cairo. 2006. page 68

- ^ Science and technology in Islam. Aḥmad Yūsuf Ḥasan, Maqbul Ahmed, A. Z. Iskandar. Paris: UNESCO Pub. 2001. p. 59. ISBN 92-3-103830-3. OCLC 61151297. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Schulze, Wolfgang. "Symbolism on the Syrian Standing Caliph Copper Coins": 19. Archived from the original on 2022-04-17. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kennedy, Hugh. ""The Impact of Muslim Rule on the Pattern of Rural Settlement in Syria," in La Syrie de Byzance à l'Islam, edd. P. Canivet and J.P. Rey-Coquais (Damascus, Institut français du Proche orient 1992) pp. 291–7": 292. Archived from the original on 2022-04-17. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Barker, John W. (1966). Justinian and the Later Roman Empire. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-299-03944-8. Archived from the original on 2022-04-17. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Shultz, Richard H.; Dew, Andrea J. (2009). Insurgents, Terrorists, and Militias: The Warriors of Contemporary Combat. Columbia University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-231-12983-1. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Shultz, Robert (2013-03-18). The Marines Take Anbar: The Four Year Fight Against al Qaeda. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-141-2. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Smet, D. De; Vermeulen, Urbain; Steenbergen, J. van; Hulster, Kristof d' (2005). Egypt and Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk Eras IV: Proceedings of the 9th and 10th International Colloquium Organized at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in May 2000 and May 2001. Peeters Publishers. p. 104. ISBN 978-90-429-1524-4. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ FRYE, Richard Nelson (May 2, 2006). "PEOPLES OF IRAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2019-05-17. Retrieved 2008-12-14.

- ^ RamHormozi, H. (2016-04-22). Averting An Iranian Geopolitical Crisis: A Tale of Power Play for Dominance Between Colonial Powers, Tribal and Government Actors in the Pre and Post World War One Era. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1-4602-8066-9. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Elling, Rasmus Christian (2013), Minorities in Iran: Nationalism and Ethnicity after Khomeini, Palgrave Macmillan US, p. 37, doi:10.1057/9781137069795, ISBN 978-1-137-06979-5

- ^ The Sinai Peninsula

- ^ Appiah, Anthony; Gates (Jr.), Henry Louis (2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 511. ISBN 978-0-19-517055-9. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Suwaed, Muhammad (2015-10-30). Historical Dictionary of the Bedouins. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4422-5451-0. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Miller, Catherine; Al-Wer, Enam; Caubet, Dominique; Watson, Janet C. E. (2007-12-14). Arabic in the City: Issues in Dialect Contact and Language Variation. Routledge. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-135-97876-1. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ a b el-Hasan, Hasan Afif (2019-05-01). Killing the Arab Spring. Algora Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-62894-349-8. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Nelson, Harold D. (1985). Morocco, a Country Study. Headquarters, Department of the Army. p. 14. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Lombardo, Jennifer (2021-12-15). Mauritania. Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-5026-6305-4. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Shoup, John (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 978-1598843620.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 103.

- ^ Ireland, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and (1888). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. The Institute. p. 16. Archived from the original on 2022-05-30. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Admin. "Eritrea: The Rashaida People". Madote. Archived from the original on 2017-07-20. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ Al Andulsi, Ibn Abd Rabuh (939). Al Aqid Al Fareed.

- ^ Al-Qthami, Hmood (1985). North of Hejaz. Jeddah: Dar Al Bayan. p. 235.

- ^ a b Ali Phd, Jawad (2001). "A Detailed Account of the History of Arabs Before Islam". Al Madinah Digital Library. Dar Al Saqi. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ Al Zibeedi, Murtathi (1965). Taj Al Aroos min Jawahir Al Qamoos.

- ^ Al Hashimi, Muhammed Ibn Habib Ibn Omaya Ibn Amir (859). Al Mahbar. Beirut: Dar Al Afaaq.

- ^ Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson, Paul Schellinger. 1995. International Dictionary of Historic Places. Vol. 3 Southern Europe. Routledge. p.190.

- ^ M. Th. Houtsma, ed. (1993). "Kinana". E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 4. pp. 1017–1018. ISBN 9789004097902.

- ^ "نهاية الأرب في معرفة أنساب العرب • الموقع الرسمي للمكتبة الشاملة". 2018-02-26. Archived from the original on 2018-02-26. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ "موسوعة تاريخ المغرب العربي - ʻAbd al-Fattāḥ Miqlad Ghunaymī, عبد الفتاح مقلد الغنيمي - كتب Google". 2019-09-03. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ "موسوعة العشائر العراقية - Thāmir ʻAbd al-Ḥasan ʻĀmirī - كتب Google". 2019-12-17. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ "ص204 - كتاب الأعلام للزركلي - يعلى بن أمية - المكتبة الشاملة الحديثة". 2021-10-02. Archived from the original on 2021-10-02. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ "الموسوعة الشاملة - قلائد الجمان في التعريف بقبائل عرب الزمان". Archived from the original on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ Fück, J. W. (2012-04-24), "G̲h̲aṭafān", Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Brill, archived from the original on 2022-03-14, retrieved 2022-08-21

- ^ a b عشائر العراق - عباس العزاوي

- ^ a b عشائر الشام-وصفي زكريا