Lagerstätte

| Part of a series on |

| Paleontology |

|---|

|

|

Paleontology Portal Category |

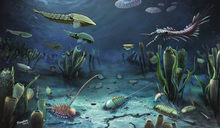

A Fossil-Lagerstätte (German: [ˈlaːɡɐˌʃtɛtə], from Lager 'storage, lair' Stätte 'place'; plural Lagerstätten) is a sedimentary deposit that exhibits extraordinary fossils with exceptional preservation—sometimes including preserved soft tissues. These formations may have resulted from carcass burial in an anoxic environment with minimal bacteria, thus delaying the decomposition of both gross and fine biological features until long after a durable impression was created in the surrounding matrix. Fossil-Lagerstätten span geological time from the Neoproterozoic era to the present.

Worldwide, some of the best examples of near-perfect fossilization are the Cambrian Maotianshan shales and Burgess Shale, the Ordovician Soom Shale, the Silurian Waukesha Biota, the Devonian Hunsrück Slates and Gogo Formation, the Carboniferous Mazon Creek, the Triassic Madygen Formation, the Jurassic Posidonia Shale and Solnhofen Limestone, the Cretaceous Yixian, Santana, & Agua Nueva formations and the Tanis Fossil Site, the Eocene Fur Formation, Green River Formation, Messel Formation & Monte Bolca, the Miocene Foulden Maar and Ashfall Fossil Beds, the Pliocene Gray Fossil Site, and the Pleistocene Naracoorte Caves & La Brea Tar Pits.

Types

[edit]Palaeontologists distinguish two kinds:[1][2]

- Konzentrat-Lagerstätten (concentration Lagerstätten) are deposits with a particular "concentration" of disarticulated organic hard parts, such as a bone bed. These Lagerstätten are less spectacular than the more famous Konservat-Lagerstätten. Their contents invariably display a large degree of time averaging, as the accumulation of bones in the absence of other sediment takes some time. Deposits with a high concentration of fossils that represent an in situ community, such as reefs or oyster beds, are not considered Lagerstätten.

- Konservat-Lagerstätten (conservation Lagerstätten) are deposits known for the exceptional preservation of fossilized organisms or traces. The individual taphonomy of the fossils varies with the sites. Conservation Lagerstätten are crucial in elucidating important moments in the history and evolution of life. For example, the Burgess Shale of British Columbia is associated with the Cambrian explosion, and the Solnhofen limestone with the earliest known bird, Archaeopteryx.

Preservation

[edit]Konservat-Lagerstätten preserve lightly sclerotized and soft-bodied organisms or traces of organisms that are not otherwise preserved in the usual shelly and bony fossil record; thus, they offer more complete records of ancient biodiversity and behavior and enable some reconstruction of the palaeoecology of ancient aquatic communities. In 1986, Simon Conway Morris calculated only about 14% of genera in the Burgess Shale had possessed biomineralized tissues in life. The affinities of the shelly elements of conodonts were mysterious until the associated soft tissues were discovered near Edinburgh, Scotland, in the Granton Lower Oil Shale of the Carboniferous.[3] Information from the broader range of organisms found in Lagerstätten have contributed to recent phylogenetic reconstructions of some major metazoan groups. Lagerstätten seem to be temporally autocorrelated, perhaps because global environmental factors such as climate might affect their deposition.[4]

A number of taphonomic pathways may produce Konservat-Lagerstätten:[5]

- Phosphatization (replacing soft tissues with phosphate, such as Orsten-type and Doushantuo-type preservations).

- Silicification (replacing or entombing soft tissues with silica, such as petrified wood or Bitter Springs-type preservation).

- Kerogenization (soft tissues converted into inert carbonaceous films, as found in Burgess Shale-type preservation).

- Aluminosilification (replacing or coating soft tissues with films of aluminosilicate minerals).

- Pyritization (replacing soft tissues with pyrite, such as the exquisite detail found in Beecher's trilobite-type preservation).

- Calcification (replacing or soft tissues with calcite minerals).

- Siderite or calcite nodules (chemicals released by decaying soft tissue modify the surrounding sediment into a siderite concretion or coal ball encasing the fossil, as found in the Mazon Creek fossil beds).

- Rapid sediment cementation (impressions of soft tissue preserved through casts and molds in the surrounding sediment, such as Ediacaran-type preservation facilitated by microbial mats).

- Amber (soft tissues encased in hardened tree resin).

The identification of a fossil site as a Konservat-Lagerstätte may be based on a number of different factors which constitute "exceptional preservation". These may include the completeness of specimens, soft tissue preservation, fine-scale detail, taxonomic richness, distinctive taphonomic pathways (often multiple at the same site), the extent of the fossil layer in time and space, and particular sediment facies encouraging preservation.[5]

Notable Lagerstätten

[edit]The world's major Lagerstätten include:

Precambrian

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonesuch Formation | 1083-1070 Ma | Michigan, USA | An oxygenated Mesoproterozoic lake[6] containing exceptionally preserved limnic microbes.[7] | |

|

Lakhanda Lagerstätte |

1030-1000 Ma |

Uchur-Maya Depression, Russia |

A site preserving a Mesoproterozoic community dominated by anaerobic bacteria.[8] The lagerstätte contains evidence of trophic interactions from the Boring Billion.[9][10] | |

|

1000–850 Ma |

South Australia |

Preserved fossils include cyanobacteria microfossils. |

| |

| Diabaig Formation | 994 ± 48 Ma[11] | Scotland | A freshwater environment preserving phosphatic microfossils,[12] which represent some of the oldest known non-marine eukaryotes.[13] | |

| Dolores Creek Formation | 950 Ma | Yukon, Canada | An Early Tonian site containing pyritised macroalgal fossils.[14] | |

|

Chichkan Lagerstätte |

775 Ma |

Kazakhstan |

A site from the transition between the prokaryote-dominated biota of the Early Neoproterozoic and the eukaryote-dominated biota of the Late Neoproterozoic and Phanerozoic.[15] | |

|

600–555 Ma |

Guizhou Province, China |

Spans the poorly understood interval between the end of the Cryogenian period and the late Ediacaran Avalon explosion. |

| |

| Portfjeld Formation | 570 Ma | North Greenland | A Middle Ediacaran biota from the continent of Laurentia exhibiting Doushantuo-type preservation.[16] | |

|

565 Ma |

Newfoundland, Canada |

This site contains one of the most diverse and well-preserved collections of Precambrian fossils. |

| |

| Itajai Biota | 563 Ma | Brazil | An Ediacaran lagerstatte preserved by volcanism.[17] | |

|

555 Ma |

South Australia |

The type location the Ediacaran period, and has preserved a significant amount of fossils from that time. |

| |

| Shibantan Lagerstätte | 551-543 Ma | Hubei, China | A terminal Ediacaran fossil assemblage preserving life forms living just before the Proterozoic-Phanerozoic transition.[18] | |

| Gaojiashan Lagerstätte | 551-541 Ma | Shaanxi, China | A lagerstätte documenting tube growth patterns of Cloudina.[19] | |

| Jiucheng Member | 551-543 Ma | Yunnan, China | A latest Ediacaran macrofossil biota dominated by giant, unbranching thallophytes.[20] | |

|

Khatyspyt Lagerstätte |

544 Ma |

Yakutia, Russia |

A Late Ediacaran lagerstätte preserving an Avalon-type biota.[21] | |

| Bernashivka open pit | ? (Upper Vendian) | Vinnytsia Oblast, Ukraine | A Late Ediacaran lagerstätte with numerous soft-bodied animals, algae, microfossils, bacteria, and fungi, comprising a number of different geological formations.[22] |

Cambrian

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhangjiagou | Fortunian | Shaanxi, China | A lagerstätte from the earliest Cambrian notable for its fossils of cnidarians,[23] cycloneuralians,[24][25] and the basal ecdysozoan Saccorhytus coronarius.[26] |  |

| Xiaoshiba Lagerstätte | Cambrian Stage 2 | Yunnan, China | A site known for its detailed preservation of Early Cambrian macroalgae.[27] | |

|

Maotianshan Shales (Chengjiang) |

518 Ma |

Yunnan, China |

The preservation of an extremely diverse faunal assemblage renders the Maotianshan shale the world's most important for understanding the evolution of early multi-cellular life. |

|

|

518 Ma |

Hubei, China |

This site is particularly notable due to both the large proportion of new taxa represented (approximately 53% of the specimens), and the notable volume of soft-body tissue preservation. |

| |

|

523-518 Ma |

A site known for its fauna, and that they were most likely preserved by a death mask. It is a part of the larger Buen Formation, and has a fauna similar to the Maotianshan shales. |

| ||

| Poleta Formation | 519-518 Ma | Nevada, USA | The middle member of the formation preserves the Indian Springs Lagerstätte, one of the oldest such sites from former Laurentia. This site preserves a diversity of mineralized organisms such as trilobites and brachiopods, but also non-mineralized remains such as sponges, algae, and soft-bodied arthropods.[28] |  |

|

518 Ma |

One of the oldest known Cambrian lagerstätten. The fauna of this site is unique, as it seems that they were adapted to living in dysaerobic conditions.[29] |

| ||

| Cranbrook Lagerstätte | Cambrian Stage 4 | British Columbia | One of the oldest Burgess Shale-type biotas of North America.[30] | |

| Tatelt Formation | 515 Ma | High Atlas, Morocco | A layer in this formation has produced some of the most well-preserved trilobites ever discovered, with preserved internal organs, feeding structures, and articulated appendages. The trilobites were likely rapidly buried and preserved by a volcanic eruption.[31] |  |

|

513 Ma |

Noted soft tissue mineralization, most often of blocky apatite or fibrous calcium carbonate, including the oldest phosphatized muscle tissue. |

| ||

| Parker Slate | 513-511 Ma | Vermont, US | A Burgess Shale-type biota with rare but exceptionally preserved soft-bodied animals. The earliest Burgess Shale-type biota to be described, being documneted 25 years before the Burgess Shale itself.[32] | |

|

513–501 Ma |

Guizhou, China |

The middle part of the Kaili Formation, the Oryctocephalus indicus Zone, contains a Burgess Shale-type lagerstätte with many well-preserved fossils known collectively as the Kaili Biota. |

| |

|

Murero Lagerstätte |

511-503 Ma |

Spain |

Thanks to the paleontological content, mainly trilobites, fourteen biozones have been established, the most precise biozonation for this time interval in the world. It also records in detail the so-called Valdemiedes event, the mass extinction episode at the end of the Lower Cambrian.[33] |

|

|

~510–500 Ma |

Central Wisconsin, US |

This site preserves some of the oldest evidence of multicellular life walking out of the ocean, and onto dry land (in the form of large mollusks and euthycarcinoid arthropods). Other notable fossils include stranded scyphozoans, and some of the oldest true crustaceans (in the form of phyllocarids). |

| |

| Henson Gletscher Formation | Wuliuan | North Greenland | A phosphatised lagerstätte preserving hatching priapulid larvae and abundant bradoriid and phosphatocopid arthropods.[34] | |

|

508 Ma |

British Columbia, Canada |

One of the most famous fossil localities in the world. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At 508 million years old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fossil beds containing soft-part imprints. |

| |

|

507 Ma |

A site known for its abundant Cambrian trilobites and the preservation of Burgess Shale-type fossils. The type locality for this site is Spence Gulch in southeastern Idaho. |

| ||

|

Linyi Lagerstätte |

504 Ma |

A lagerstätte recognised for its exceptional preservation of arthropod limbs, intestines, and eyes.[35] |

| |

| Ravens Throat River Lagerstätte | Drumian | Northwest Territories | A Burgess Shale-type biota coeval in age with the more famous Wheeler Shale and Marjum Formation.[36] | |

|

504 Ma |

Western Utah, US |

A world-famous locality known for its prolific agnostid and Elrathia kingii trilobite remains. Varied soft bodied organisms are also locally preserved, including Naraoia, Wiwaxia and Hallucigenia. |

| |

|

502 Ma |

Western Utah, US |

A site known for its occasional preservation of soft-bodied tissue, and diverse assemblage. |

| |

|

500 Ma |

Western Utah, US |

A site that is dominated by trilobites and brachiopods, but also comprising various soft-bodied organisms, such as Falcatamacaris. |

| |

|

Kinnekulle Orsten and Alum Shale |

500 Ma |

The Orsten sites reveals the oldest well-documented benthic meiofauna in the fossil record. Fossils such as microfossils of arthropods like free-living pentastomids are known. Multiple "Orsten-type" lagerstätten are also known from other countries. |

|

Ordovician

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

about 485 Ma |

Draa Valley, Morocco |

It was deposited in a marine environment, and is known for its exceptionally preserved fossils, filling an important preservational window beyond the earlier and more common Cambrian Burgess shale-type deposits. |

| |

| Cabrieres biota | Floian | Montagne Noire, France | A polar marine ecosystem from the Early Ordovician that likely served as a refuge from the high temperatures of the epoch.[37] | |

|

Liexi fauna |

About 470 Ma (early-middle Floian) |

Hunan Province, China |

Preserves Early Ordovician fauna with soft tissue, includes not only Cambrian relics but also taxa originated during Ordovician.[38] | |

|

About 461 Ma |

Llandrindod Wells, Wales |

A unique environment deposited during the middle Ordovician that possibly shows iconic groups from Cambrian lagerstättes, like Opabiniids and Megacheirans, survived for longer than what was thought. |

| |

|

460 Ma |

Tennessee, US |

Low-diversity assemblage of arthropod fossils, which are preserved well because of volcanic ash. |

| |

|

460 Ma |

A Middle Ordovician site confined to a large impact Crater that is known for exceptionally exquisite preservation of conodonts, bivalved arthropods, and the earliest eurypterids in the fossil record.[40] |

| ||

|

460? Ma |

New York, US |

Noted exceptionally preserved trilobites with soft tissue preserved by pyrite replacement. |

| |

|

? (Sandbian) |

Colorado, US |

Although preservation is not excellent, this lagoonal site provides early vertebrate fossils such as Astraspis and Eriptychius. |

| |

|

about 455? Ma |

New York, US |

This site is an excellent example of an obrution (rapid burial or "smothered") Lagerstätte. |

| |

| Big hill Lagerstätte | about 450? Mya | Michigan, US | A site known for its preservation of soft-bodied medusae (jellyfish), as well as linguloid brachiopods, algae, and arthropods (namely chasmataspidids, leperditid ostracods, and eurypterids). |  |

|

Brechin Lagerstätte |

450 Ma |

Ontario, Canada |

Known for preserving one of the most diverse crinoid fauna of the Katian.[41] |

|

|

450? Ma |

South Africa |

Known for its remarkable preservation of soft-tissue in fossil material. Deposited in still waters, the unit lacks bioturbation, perhaps indicating anoxic conditions. |

| |

|

Tafilalt, Morocco |

Known from range of non-biomineralised and soft-bodied organisms in polar environment.[42] |

| ||

|

? (middle Katian) |

Manitoba, Canada |

Fossils like algae, conulariids and trilobites are known from this site. | ||

|

449-445.6 Ma |

Manitoulin, Canada |

Low-diversity assemblage of arthropod fossils. |

| |

|

William Lake (Stony Mountain Formation)[39] |

445 Ma |

Manitoba, Canada |

Well-preserved fossils like jellyfish, xiphosurans, sea spiders are known from this site, it is important since many of the fossils are unknown in other Ordovician sites. |

|

|

Airport Cove[39] |

445 Ma |

Manitoba, Canada |

Fossils like eurypterids, algae and xiphosurans are preserved in this site. |

Silurian

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kalana Lagerstätte |

~440 Ma |

Estonia |

Known for well preserved fossils of algae and crinoids,[43] along with an osteostracan fossilised via an extremely unusual carbonaceous mode of preservation that was previously unknown among vertebrates.[44] |

|

|

Chongqing Lagerstätte (Huixingshao Formation)[45] |

436 Ma |

Chongqing, China |

This site preserved complete fossils of earliest jawed vertebrates, as well as some galeaspids and eurypterids. |

|

|

~435 Ma |

Wisconsin, US |

Well-studied site known for the exceptional preservation of its diverse, soft-bodied and lightly skeletonized fauna, includes many major taxa found nowhere else in strata of similar age. It was one of the first fossil sites with soft bodied preservation known to science. |

| |

|

Herefordshire Lagerstätte (Coalbrookdale Formation) |

~430 Ma |

Known for the well-preserved fossils of various invertebrate animals many of which are in their three-dimensional structures. Fossils are preserved within volcanic ash, because of that sometimes this site has been compared to Pompeii.[46] Some of the fossils are regarded as earliest evidences and evolutionary origin of some of the major groups of modern animals. |

| |

|

~425 Ma |

Known for preservation of both hard and soft bodied organisms in great detail, including early scorpions, eurypterids, agnathan vertebrates, and several other species. |

| ||

|

422.9-416 Ma |

Ontario & New York State |

This limestone have produced thousands of fossil eurypterids, such as giant Acutiramus and well-known Eurypterus, as well as other fauna like scorpions and fish. |

| |

|

~420 Ma |

Pennsylvania, US |

Known from exceptionally preserved mass assemblage of Eurypterus, the most abundant eurypterid in the fossil record. |  | |

|

415 Ma[48] |

New York, US and Ontario, Canada |

Echinoderms (such as crinoids) and trilobites are known from Lewiston Member in this shale. |  |

Devonian

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhynie chert | 400 Ma | Scotland, UK | The Rhynie chert contains exceptionally preserved plant, fungus, lichen and animal material (euthycarcinoids, branchiopods, arachnids, hexapods, etc) preserved in place by an overlying volcanic deposit and hot springs. As well as one of the first known fully terrestrial ecosystems. |  |

| Waxweiler Lagerstätte (Klerf Formation) | 409-392 Ma | Eifel, Germany | Waxweiler Lagerstätte is known from well-preserved fossils of chelicerates, giant claw of Jaekelopterus rhenaniae shows the largest arthropod ever known. |  |

| Heckelmann Mill | 395 Ma | Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany | Heckelmann Mill preserves well preserved rhinocaridid archaeostracan phyllocarids,[49] along with exceptionally abundant crinoid holdfasts from the late Emsian.[50] | |

| Hunsrück Slates (Bundenbach) | 390 Ma | Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany | The Hunsrück slates are one of the few marine Devonian lagerstätte having soft tissue preservation, and in many cases fossils are coated by a pyritic surface layer. |  |

| Gogo Formation | 380 Ma (Frasnian) | Western Australia | The fossils of the Gogo Formation display three-dimensional soft-tissue preservation of tissues as fragile as nerves and embryos with umbilical cords. Over fifty species of fish have been described from the formation, and arthropods. |  |

| Miguasha National Park (Escuminac Formation) | 370 Ma | Québec, Canada | Some of the fish, fauna, and spore fossils found at Miguasha are rare and ancient species. For example, Eusthenopteron is sarcopterygian that shares characters with early tetrapods. |  |

| Kowala Lagerstätte | ~368 Ma | Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, Poland | A Late Devonian site known for its fossils of non-biomineralised algae and arthropods.[51] | |

| Maïder Basin | 368 Ma (for Thylacocephalan Layer) | Anti-Atlas, Morocco | Thylacocephalan Layer and Hangenberg Black Shale in this basin provides well-preserved fossils of Famennian fauna, including chondrichthyans and placoderms that preserved soft tissues.[52] |  |

| Strud[53] | ? (Late Famennian) | Namur Province, Belgium | Mainly juvenile placoderms are known, suggesting this site would be nursery site of placoderms.[54] Various biota like tetrapods, arthropods and plants are also known, Strudiella from this site may be the earliest insect, but its affinity is disputed. |  |

| Canowindra, New South Wales (Mandagery Sandstone) | 360 Ma | Australia | An accidentally discovered lagerstätte known for its exceptional preservation of Sarcopterygian and Placoderm fish. |  |

| Waterloo Farm Lagerstätte (Witpoort Formation) | 360 Ma | South Africa | Important site that providing the only record of a high latitude (near polar) coastal ecosystem, overturning numerous assumptions about high latitude conditions during the latest Devonian. |  |

Carboniferous

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granton Shrimp Bed | ? (Dinantian) | Firth of Forth, Scotland | Dominated by well-preserved crustacean fossils, this site provided first body fossil of Clydagnathus which solved long-lasted mystery of conodont fossils. | |

| East Kirkton Quarry[55] | 335 Ma | West Lothian, Scotland | This site has produced numerous well-preserved fossils of early tetrapods like temnospondyls or reptiliomorphs, and large arthropods like scorpions or eurypterids. |  |

| Bear Gulch Limestone | 324 Ma | Montana, US | A limestone-rich geological lens in central Montana. It is renowned for its unusual and ecologically diverse fossil composition of chondrichthyans, the group of cartilaginous fish containing modern sharks, rays, and chimaeras. Other animals like brachiopods, ray finned fish, arthropods, and the possible mollusk Typhloesus are also known from the site. |  |

| Wamsutta Formation | ~320-318 Ma | Massachusetts | A subhumid alluvian fan deposit that preserves ichnofossils, plants, invertebrates, and vertebrates.[56] | |

| Bickershaw[57] | ? (Langsettian) | Lancashire, England | This locality contains exceptionally preserved fossils within nodules. Arthropods have greater diversity, many of which are aquatic ones that lived in brackish environment. |  |

| Joggins Fossil Cliffs (Joggins Formation) | 315 Ma | Nova Scotia, Canada | A fossil site that preserves a diverse terrestrial ecosystem consisting of plants like lycopsids, giant arthropods, fish, and the oldest known sauropsid, Hylonomus. |  |

| Castlecomer fauna | 315-307 | Kilkenny, Ireland | A konservat-lagerstätte with a high number of well-preserved spinicaudatan clam shrimp.[58][59] | |

| Linton Diamond Coal Mine[60][61] | 310 Ma | Ohio, US | A site known for its number of prehistoric tetrapods, like the lepospondyl Diceratosaurus.[62] |  |

| Mazon Creek | 310 Ma | Illinois, US | A conservation lagerstätte found near Morris, in Grundy County, Illinois. The fossils from this site are preserved in ironstone concretions with exceptional detail. The fossils were preserved in a large delta system that covered much of the area. The state fossil of Illinois, the enigmatic animal Tullimonstrum, is only known from these deposits. |  |

| Buckhorn Asphalt Quarry | ~310 Ma | Oklahoma, USA | A quarry of the Boggy Formation known for its exceptionally rich orthocerid assemblage.[63] | |

| Kinney Brick Quarry (Atrasado Formation) | around 307 Ma | New Mexico, US | This site is known from rich fish fossils with preserved soft tissues, that lived in lagoonal environment. Dozens of fish genera are known, ranging from chondrichthyans like ctenacanths and hybodonts, to actinopterygians and sarcopterygians.[64] |  |

| Campáleo Outcrop | Gzhelian | Santa Catarina, Brazil | A fungal and palynological lagerstätte from Gondwana during Late Palaeozoic Ice Age.[65] | |

| Montceau-les-Mines | 300 Ma | France | Exceptional preservation of Late Carboniferous fossil biota are known, including various vertebrates and arthropods, as well as plants.[66][67] |  |

| Hamilton Quarry | 300 Ma | Kansas, US | This site is known for its diverse assemblage of unusually well-preserved marine, euryhaline, freshwater, flying, and terrestrial fossils (invertebrates, vertebrates, and plants). This extraordinary mix of fossils suggests it was once an estuary. |  |

| Carrizo Arroyo | ? (Latest Gzhelian to earliest Asselian) | New Mexico, US | This site is known from exceptional preservation of arthropod fossils, mainly insects.[68] |

Permian

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiyuan Formation | 298 Ma | Inner Mongolia, China | Known from exceptionally well-preserved plant fossils in volcanic ash.[69][70] | |

| Meisenheim Formation[71] | ?(Asselian to early Sakmarian)[72] | Lebach, Germany | This site is well-known for the rich occurrence of fauna lived in large freshwater lakes, including fish, temnospondyls, insects and others. |  |

| Franchesse | 292 Ma | Massif Central, France | A Sakmarian seymouriamorph lagerstätte from the Bourbon l'Archambault Basin in the French Massif Central containing hundreds of complete seymouriamorph specimens.[73] | |

| Chemnitz petrified forest | 291 Ma | Saxony, Germany | A petrified forest in Germany that is composed of Arthropitys bistriata, a type of Calamites, giant horsetails that are ancestors of modern horsetails, found on this location with never seen multiple branches. Many more plants and animals from this excavation are still in an ongoing research.[74] |  |

| Mangrullo Formation | about 285–275 Ma (Artinskian) | Uruguay | This site is known for its abundant mesosaur fossils. It also contains the oldest known konservat-lagerstätte in South America, as well as the oldest known fossils of amniote embryos.[75] |  |

| Chekarda (Koshelevka Formation) | about 283–273 Ma | Perm, Russia | Over 260 species of insect species are described from this site as well as diverse taxa of plants, making it one of the most important Permian konservat-lagerstätten.[76] |  |

| Toploje Member | 273-264 Ma | Prince Charles Mountains, Antarctica | This site preserves a high-latitude fauna in exceptional position before the large extinctions that happened later in the Permian.[77] | |

| Onder Karoo | 266.9–264.28 Ma | Karoo Basin, South Africa | A high latitude, cool-temperate lacustrine ecosystem preserving detailed plant and insect fossils.[78] | |

| Sakamena Group[79] | 260–247 Ma | Madagascar | Lower Sakamena Formation (Permian) and Middle Sakamena Formation (Triassic) contain fossils of animals lived around wetland environment, such as semi-aquatic and gliding neodiapsids. |  |

| Kupferschiefer | 259–255 Ma | Central Europe | This site deposited in an open marine and shallow marine environment provides fossils of reptiles as well as many fish. |  |

| Huopu Lagerstätte | ~255 Ma | Guizhou, China | A plant fossil site documenting floral dynamics between the end-Guadalupian and end-Permian extinction events.[80] |

Triassic

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guiyang biota[81] | 250.8 Ma | Guizhou Province, China | The oldest known Mesozoic lagerstätte (Dienerian). It preserves taxa belonging to 12 classes and 19 orders, including several species of fish. |  |

| Paris biota[82] | ~249 Ma | Idaho, Nevada, USA | This earliest Spathian aged assemblage preserves fossils belonging to 7 phyla and 20 orders, combining Paleozoic groups (e.g. leptomitid protomonaxonid sponges otherwise known from the early Paleozoic) with members of the Modern evolutionary fauna (e.g. gladius-bearing coleoids). |  |

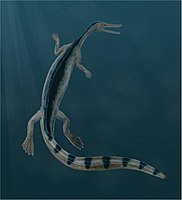

| Jialingjiang Formation[83] | 249.2–247.2 Ma | Hubei Province, China | This site preserved aquatic reptiles soon after Permian extinction. Hupehsuchians are exclusively known from here, and already got unique ecology like filter feeding. |  |

| Nanlinghu Formation[83] | 248 Ma | Anhui Province, China | This site provides important fossils to show early evolution of ichthyosauriforms. |  |

| Petropavlovka Formation | 248 Ma | Orenburg Oblast, Russia | A site known for preserving oligochaetes, whose fossil record is extremely sparse.[84] | |

| Zarzaïtine Formation | Olenekian-Anisian | In Amenas, Algeria | A site with a high number of exceptionally well-preserved temnospondyl specimens, indicating of a seasonal climate with sudden droughts, with a freshwater ecosystem that could rapidly turn into a sebkha.[85] | |

| Luoping Biota (Guanling Formation)[86] | ~247-245 Ma | Yunnan, China | Various marine animals are preserved in this site, showing how marine ecosystem recovered after Permian extinction.[87] |  |

| Grès à Voltzia | 245 Ma | France | A fossil site remarkable for its detailed myriapod specimens.[88] It also contains the earliest known aphid fossils.[89] | |

| Fossil Hill Member | ? (Anisian) | Nevada, US | One of many Anisian marine lagerstatte, the Fossil Hill Member represents an open-ocean environment with a well-preserved fauna largely dominated almost entirely by ichthyosaurs.[87] |  |

| Vossenveld Formation | ? (Anisian) | Winterswijk,Netherlands | An exposure of this Muschelkalk formation in the Winterswijk quarry has a diverse assemblage of well-preserved marine reptiles, amphibians, fishes, and plants. It is the only marginal marine assemblage recorded from the earlier Triassic.[87] | |

| Strelovec Formation | ? (Anisian) | Slovenia | A formation with well-preserved Triassic horseshoe crabs.[90] | |

| Saharonim Formation | Late Anisian/Lower Ladinian | Southern District, Israel | One brachiopod-dominated horizon of this formation documents the rapid burial of a community of exclusively juvenile Coenothyris brachiopods and ten different bivalve genera.[91] | |

| Besano Formation[83] | 242 Ma | Alps, Italy and Switzerland | This formation is designated as a World Heritage Site, as it is famous for its preservation of Middle Triassic marine life including fish and aquatic reptiles.[87][92] | |

| Xingyi biota (Zhuganpo Formation)[83] | ? (Upper Ladinian - Lower Carnian) | Guizhou and Yunnan, China | Previously considered as part of Falang Formation, this site yields many articulated skeletons of marine reptiles, as well as fish and invertebrates. |  |

| Guanling biota (Xiaowa Formation)[83] | ? (Carnian) | Guizhou, China | Like Xingi Biota, this site also yields well-preserved marine fauna, especially many species of thalattosaurs are known. |  |

| Polzberg | 233 Ma | Austria | A site from the Reingrabener Schiefer known for exceptional preservation of bromalites[93] and of cartilage,[94] deposited during the Carnian Pluvial Event.[95] |  |

| Madygen Formation | 230 Ma | Kyrgyzstan | The Madygen Formation is renowned for the preservation of more than 20,000 fossil insects, making it one of the richest Triassic lagerstätten in the world. Other vertebrate fossils as fish, amphibians, reptiles and synapsids have been recovered from the formation too, as well as minor fossil flora. |  |

| Cow Branch Formation | 230 Ma | Virginia, US | This site preserves a wide variety of organisms (including Fish, reptiles, arachnids, and insects). |  |

| Alakir Çay | ? (Norian) | southwest Turkey | A konservat-lagerstätte with exceptionally well-preserved Triassic corals, retaining much of their original aragonite skeletons.[96] |

Jurassic

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteno (Moltrasio Formation)[97] | 196-188 Ma | Italy | Several kinds of marine biota such as fish, crustaceans, cephalopods polychaetes, and nematodes have been recovered. This site is the only fossil deposit in Italy in which soft bodies are preserved other than Monte Bolca. |  |

| Ya Ha Tinda | 183 Ma | Alberta, Canada | A fossil site notable for containing abundant and extremely well-preserved vampire squid, being the largest concentration of vampire squid fossils outside the Tethys Ocean,[98] and for being deposited during the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (TOAE).[99][100][101] | |

| Strawberry Bank | 183 Ma | Somerset, England | A site from the TOAE documenting marine life during the recovery from the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event as well as the turmoil of the TOAE.[102] The oldest pseudoplanktonic barnacles in the fossil record,[103] near-complete ichthyosaur skeletons,[104] and evidence of ichthyosaur niche partitioning are preserved at this site.[105] | |

| Holzmaden/Posidonia Shale | 183 Ma | Württemberg, Germany | The Sachrang member is among the most important formations of the Toarcian boundary, due to the concentrations of exceptionally well-preserved complete skeletons of fossil marine fish and reptiles. It was also deposited during the TOAE.[106][107] |  |

| Cabeço da Ladeira | Late Bajocian | Portugal | A site known for exquisite preservation of microbial mats in a tidal flat.[108] | |

| Monte Fallano | ? (Bajocian-Bathonian) | Campania, Italy | This Plattenkalk preserves fossils of terrestrial plants, crustaceans and fish.[109] | |

| Christian Malford | Callovian | Wiltshire, England | A site in the Oxford Clay Formation which preserves exceptionally detailed coleoid fossils.[110] | |

| Mesa Chelonia[111] | 164.6 Ma | Shanshan County, China | This site is notable because it contains a large turtle bonebed, containing specimens of the genus Annemys. This bonebed contains up to an estimated 36 turtles per square meter. | |

| La Voulte-sur-Rhône | 160 Mya | Ardèche, France | La Voulte-sur-Rhône, in the Ardèche region of southwestern France, offers paleontologists an outstanding view of an undisturbed paleoecosystem that was preserved in fine detail. Notable finds include retinal structures in the eyes of thylacocephalan arthropods, and fossilized relatives of the modern day vampire squid, like Vampyronassa rhodanica. |  |

| Shar Teeg Beds | 160-145 Mya | Govi-Altay, Mongolia | Many of insect remains and some vertebrates like relatives of crocodilians are known from this site.[112] | |

| Karabastau Formation | 155.7 Ma | Kazakhstan | This site is an important locality for insect fossils that has been studied since the early 20th century, alongside the rarer remains of vertebrates, including pterosaurs, salamanders, lizards and crocodiles. |  |

| Tiaojishan Formation | 165-153 Ma | Liaoning Province, China | It is known for its exceptionally preserved fossils, including those

of plants, insects and vertebrates. It is made up mainly of pyroclastic rock interspersed with basic volcanic and sedimentary rocks. |

|

| La Casita Formation | Kimmeridgian | Coahuila, Mexico | A marine konzentrat-lagerstätte deposited in a hemipelagic mud bottom during dysoxic conditions.[113] | |

| Talbragar fossil site[114] | 151 Ma | New South Wales, Australia | This bed is part of Purlawaugh Formation, and provided fauna like fish and insects that lived around the lake. |  |

| Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry | 150 Ma | Utah, US | Jurassic National Monument, at the site of the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, well known for containing the densest concentration of Jurassic dinosaur fossils ever found, is a paleontological site located near Cleveland, Utah, in the San Rafael Swell, a part of the geological layers known as the Morrison Formation. Up to 15,000 have been excavated from this site alone. |  |

| Canjuers Lagerstätte | 150 Ma | France | This site shows a high amount of biodiversity, including reptiles, invertebrates, fish, and other organisms. |  |

| Agardhfjellet Formation | 150-140 Ma | Spitsbergen, Norway | The formation contains the Slottsmøya Member, a highly fossiliferous unit where many ichthyosaur and plesiosaur fossils have been found, as well as abundant and well preserved fossils of invertebrates. |  |

| Solnhofen Limestone | 149-148 Ma | Bavaria, Germany | This site is unique as it preserves a rare assemblage of fossilized organisms, including highly detailed imprints of soft bodied organisms such as sea jellies. The most familiar fossils of the Solnhofen Plattenkalk include the early feathered theropod dinosaur Archaeopteryx preserved in such detail that they are among the most famous and most beautiful fossils in the world. |  |

| Owadów–Brzezinki site | ~148 Ma | Łódź Voivodeship, Poland | A marine deposit of the Kcynia Formation similar to the Solnhofen Formation, with large numbers of preserved insect remains, numerous marine invertebrates, and vertebrates including fishes, marine reptiles, and pterosaurs.[115][116] |  |

Cretaceous

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angeac-Charente bonebed | ~141 Ma | Charente, France | A lagerstätte preserving both vertebrate and invertebrate fossils from the poorly represented Berriasian stage known for its taphonomic and sedimentological ‘frozen scenes’.[117] | |

| El Montsec (La Pedrera de Rúbies Formation) | ~140-125 Ma | Catalonia, Spain | Known from exceptional preservation of biota such as plants, fish, insects, crustaceans and even some tetrapods.[118] |  |

| Lebanese amber | ~130-125 Ma (Barremian) | Lebanon | Preserves a high diversity of insects from the Early Cretaceous, and is among the oldest known fossilized amber to contain a significant number of preserved organisms.[119] Includes many of the oldest known members of modern insect groups, and many of the youngest known members for extinct insect groups.[120] |  |

| Las Hoyas | about 125 Ma (Barremian) | Cuenca, Spain | The site is mostly known for its exquisitely preserved dinosaurs, especially enantiornithines. The lithology of the formation mostly consists of lacustarine limestone deposited in a freshwater wetland environment. |  |

| Yixian Formation | about 125–121 Ma (Barremian-Aptian) | Liaoning, China | The Yixian Formation is well known for its great diversity of well-preserved specimens and its feathered dinosaurs, such as the large tyrannosauroid Yutyrannus, the therizinosaur Beipiaosaurus, and various small birds, along with a selection of other dinosaurs, such as the iguanodontian Bolong, the sauropod Dongbeititan and the ceratopsian Psittacosaurus. Other biota included the troodontid Mei, the dromaeosaurid Tianyuraptor, and the compsognathid Sinosauropteryx. |  |

| Jiufotang Formation | about 122-119 Ma (Aptian) | Liaoning, China | This formation overlies the slightly older Yixian Formation and preserved very similar species, including a wide variety of dinosaurs such as the ceratopsian Psittacosaurus and the early bird Confuciusornis, both of which are also found in the Yixian Formation. Also notable are the very abundant specimens of the dromaeosaurid Microraptor, which is known from up to 300 specimens and is among the most common animals found here. |  |

| Khasurty Fossil Site | ? (Aptian) | Buryatia, Russia | One of the largest fossil insect sites in northern Asia, with over 6000 fossilized insect specimens preserved in mudstones, representing over 16 orders and 130 families. Taxa have both Jurassic & Cretaceous affinities. Fossils of other invertebrates such as arachnids & crustaceans are also known, in addition to small plants and fragmentary vertebrate remains such as fish scales and bird feathers.[121] | |

| Shengjinkou Formation | about 120 Ma | Xinjiang, China | Part of the finds from this site consisted of dense concentrations of pterosaur bones, associated with soft tissues and eggs. The site represented a nesting colony that storm floods had covered with mud. Dozens of individuals could be secured from a total that in 2014 was estimated to run into the many hundreds. |  |

| Xiagou Formation | about 120–115? Ma | Gansu, China | This site is known outside the specialized world of Chinese geology as the site of a lagerstätte in which the fossils were preserved of Gansus yumenensis, the earliest true modern bird. |  |

| Paja Formation | 130-113 Ma | Colombia | This site is famous for its vertebrate fossils and is the richest Mesozoic fossiliferous formation of Colombia. Several marine reptile fossils of plesiosaurs, pliosaurs, ichthyosauras and turtles have been described from the formation and it hosts the only dinosaur fossils described in the country to date; the titanosauriform sauropod Padillasaurus. |  |

| Koonwarra Fossil Bed[122] | around 118-115 Ma | Victoria, Australia | This site is composed of mudstone sediment thought to have been laid down in a freshwater lake. Arthropods, fish and plant fossils are known from this site. |  |

| Crato Formation | 113 Ma | northeast Brazil | The Crato Formation earns the designation of lagerstätte due to an exceedingly well preserved and diverse fossil faunal assemblage. Some 25 species of fossil fishes are often found with stomach contents preserved, enabling paleontologists to study predator-prey relationships in this ecosystem. There are also fine examples of pterosaurs, reptiles and amphibians, invertebrates (particularly insects), and plants. Also known from this site is Ubirajara, the first non-avian dinosaur from the southern hemisphere with evidence of feathers. Additionally, the formation abounds with evidence of plant-insect interaction.[123] |  |

| Amargosa Bed (Marizal Formation) | ? (Aptian-Albian) | northeast Brazil | Fluvial site which preserved fish, crustacean and plant fossils.[124] | |

| Pietraroja Plattenkalk | 113-110 Ma | Campania, Italy | A konservat-lagerstätte famous for its diverse and well-preserved fish and plant fossils. Also known from this formation is Scipionyx, one of Europe's most well-preserved dinosaurs.[125][126] |  |

| Jinju Formation | 112.4–106.5 Ma | South Korea | The Jinju Formation is notable for the post-Jehol Group insect assemblage,[127] as well as other fauna such as isopods and fish.[128][129] The site is also notable for its abundance and diversity of tetrapod trackways.[130] |  |

| Tlayúa Formation | 110 Ma | Puebla, Mexico | A marine lagerstätte preserving Albian actinopterygians and lepidosaurs.[131] |  |

| Romualdo Formation | 108–92 Ma | northeast Brazil | The Romualdo Formation is a part of the Santana Group and has provided a rich assemblage of fossils; flora, fish, arthropods insects, turtles, snakes, dinosaurs, such as Irritator, and pterosaurs, including the genus Thalassodromeus. The stratigraphic units of the group contained several feathers of birds, among those the first record of Mesozoic birds in Brazil. |  |

| Muhi Quarry (El Doctor Formation) | ? (Albian to Cenomanian, probably Late Albian)[132] | Hidalgo, Mexico | While this site produced limestones for construction, rocks in that locality contain a diverse Cretaceous marine biota such as fish, ammonites and crustaceans. |  |

| Puy-Puy Lagerstätte | 100.5 Ma | France | A paralic site preserving a variety of ichnofossils,[133] along with some vertebrate remains.[134] The site preserves evidence of plant-insect interaction.[135] | |

| Burmese amber | 101-99 Ma (latest Albian/earliest Cenomanian) | Myanmar | More than 1,000 species of taxa have been described from ambers from Hukawng Valley. While it is important for understanding the evolution of biota, mainly insects, during the Cretaceous period, it is also extremely controversial by facing ethical issues due to its association with conflicts and labor conditions. |  |

| English Chalk | 100-90 Ma (Cenomanian to Turonian) | England | Two subsections of England's famous chalk formation, the Grey Chalk Subgroup and the lower sections of the White Chalk Subgroup, yield three-dimensionally preserved fossils of marine fishes. This exquisite level of preservation is unlike fish fossils from other deposits from around the same time, which are only preserved as two-dimensional compression fossils.[136] |  |

| Haqel/Hjoula/al-Nammoura | 95-94 Ma | Lebanon | Famous Lebanese konservat-lagerstätten of the Late Cretaceous (middle to late Cenomanian) age, which contain a well-preserved variety of different fossils. Small animals like shrimp, octopus, stingrays, and bony fishes are common finds at these sites. Some of the rarest fossils from this locality include those of octopuses.[137] |  |

| Komen Limestone | 95-94 Ma | Komen, Slovenia | A Late Cenomanian locality in the Karst of Slovenia with a high diversity of articulated fossil fish, in addition to small reptiles and invertebrates.[138] |  |

| Hesseltal Formation | 94–93 Ma | Saxony & North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany | Deposited during the anoxic conditions of the Cenomanian-Turonian boundary event, this formation has a high number of well-preserved, articulated fish skeletons, in addition to exceptionally preserved ammonites with soft parts.[139][140] | |

| Vallecillo (Agua Nueva Formation) | 94–92 Ma | Nuevo León, Mexico | The site is noted for its qualities as a konservat-lagerstätte, with notable finds including the plesiosaur Mauriciosaurus and the possible shark Aquilolamna. |  |

| Akrabou Formation (Gara Sbaa/Agoult & Goulmima) | ? (Turonian) | Asfla, Morocco | Marine site known for exceptionally preserved, three-dimensional fish fossils.[141][142] |  |

| Orapa diamond mine | Turonian | Botswana | An insect lagerstätte known for being one of the few entomofaunas from southern Africa, containing a variety of insects,[143] particularly beetles.[144][145] | |

| New Jersey amber | 91-89 Ma | New Jersey, US | Turonian-aged amber from the Raritan & Magothy Formations of New Jersey, with a high diversity of well-preserved insects, plants and fungi.[146] |  |

| Lower Idzików beds | 87-86 Ma (Coniacian) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Poland | An exposure of these beds near Stary Waliszów contains a konzentrat-lagerstätte of numerous Cretaceous marine invertebrates in concretions, including decapods, molluscs and echinoderms, as well as well-preserved plant fossils that indicate a nearshore environment. Very well-preserved phosphatized decapod remains are known.[147] | |

| Smoky Hill Chalk | 87–82 Ma | Kansas and Nebraska, US | A Cretaceous konservat-lagerstätte known primarily for its exceptionally well-preserved marine reptiles. Also known from this site are fossils of large bony fish such as Xiphactinus, mosasaurs, flying reptiles or pterosaurs (namely Pteranodon), flightless marine birds such as Hesperornis, and turtles. |  |

| Ingersoll Shale | 85 Ma | Alabama, US | A Late Cretaceous (Santonian) informal geological unit in eastern Alabama. Fourteen theropod feathers assigned to birds and possibly dromaeosaurids have been recovered from the unit. | |

| Sahel Alma | ~84 Ma | Lebanon | A Late Cretaceous (Santonian) konservat-lagerstätte with similar excellent preservation of marine organisms as the nearby, older Sannine Lagerstätte, but in a deep-water environment. Includes a high number of well-preserved shark body fossils, in addition to cephalopods and deepwater arthropods.[137] |  |

| Auca Mahuevo | 80 Ma | Patagonia, Argentina | A Cretaceous lagerstätte in the eroded badlands of the Patagonian province of Neuquén, Argentina. The sedimentary layers of the Anacleto Formation at Auca Mahuevo were deposited between 83.5 and 79.5 million years before the present and offers a view of a fossilized titanosaurid nesting site. |  |

| Ellisdale Fossil Site | 79-76 Ma | New Jersey, US | A middle Campanian konzentrat-lagerstätte from the Marshalltown Formation with one of the most diverse Mesozoic vertebrate faunas of eastern North America, likely originating from a flood event. A high number of disarticulated bones of dinosaurs, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and small mammals is known, most of which are microfossils.[148] | |

| Coon Creek Formation | 76.8-76.0 Ma[149] | Tennessee and Mississippi, US | This late Campanian formation has some of the world's best-preserved remains of Cretaceous marine invertebrates (primarily mollusks and decapod crustaceans), with many retaining their original aragonitic shells and exoskeletons.[149][150] |  |

| Baumberge Formation | ~75-72 Ma | North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany | A Late Campanian formation in the Baumberge of Germany with a high number of articulated fossil fish remains, in addition to shark body fossils.[139][151] |  |

| Nardò (Calcari di Melissano)[152] | ~72-70 Ma (upper Campanian-lower Maastrichtian) | Apulia, Italy | This site is especially famous for its limestones containing abundant fossil fish remains. |  |

| Harrana (Muwaqqar Chalk Marl Formation) | 66.5-66.1 Ma (Late Maastrichtian)[153] | Jordan | Phosphatic deposits formed in this site are known to preserve vertebrate fossils with soft tissue, such as mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, sharks, bony fish, turtles and crocodylians.[154] |  |

| Zhucheng (Wangshi Group) | 66 Ma | Shandong, China | Zhucheng has been an important site for dinosaur excavation since 1960. The world's largest hadrosaurid fossil (Shantungosaurus) was found in Zhucheng in the 1980s. Other dinosaurs known from the area include the ceratopsian Zhuchengceratops (2010), the sauropod Zhuchengtitan (2017) and the theropod Zhuchengtyrannus (2011) which have all been described from deposits near and named after Zhucheng. |  |

| Tanis[155] | 66.0 Ma | North Dakota, US | Tanis is part of the heavily studied Hell Creek Formation, a group of rocks spanning four states in North America renowned for many significant fossil discoveries from the Upper Cretaceous and lower Paleocene. Tanis is a significant site because it appears to record the events from the first minutes until a few hours after the impact of the giant Chicxulub asteroid in extreme detail. This impact, which struck the Gulf of Mexico 66.043 million years ago, wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs and many other species (the so-called "K-Pg" or "K-T" extinction). |  |

Paleogene

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baunekule Facies | 64-63 Ma (Danian) | eastern Denmark | These facies of the Faxe Formation document an extremely well-preserved cold-water coral mound ecosystem dominated by Dendrophyllia corals, and also includes gastropods, tubeworms, bivalves, bryozoans and gastropods.[156] | |

| Tenejapa-Lacandón Formation | ~63 Ma | Chiapas, Mexico | A formation with a high number of well-preserved fish fossils indicative of mass mortality events.[157] One of the most important formations for documenting the recovery of ocean ecosystems in the wake of the K-Pg extinction, due to being deposited just a few million years after and being located only 500 kilometres (310 mi) away from the Chixculub impact site.[158] |  |

|

Menat |

60 Ma |

Auvergne, France |

A Palaeocene maar lake containing three-dimensional plant remains.[159] It is particularly notable for preserving one of the oldest known bees.[160] |

|

| Danata Formation | 56-53 Ma | western Turkmenistan | Outcropping in the Kopet Dag range, this formation preserves numerous fossil fish from a northeastern arm of the Tethys Ocean during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. 38 taxa from 13 orders are known, the vast majority of which are acanthomorphs.[161][162] |  |

|

55–53 Ma |

Preserves abundant fossil fish, insects, reptiles, birds and plants. The Fur Formation was deposited about 55 Ma, just after the Palaeocene-Eocene boundary, and its tropical or sub-tropical flora indicate that the climate after the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum was moderately warm (approximately 4-8 degrees warmer than today). |

| ||

|

54–48 Ma |

England, UK |

Collected for close to 300 years, Plant fossils, especially seeds and fruits, are found in abundance. |

| |

|

52 - 48 Ma |

British Columbia, Canada & Washington, USA |

Includes McAbee Fossil Beds, Princeton chert & Klondike Mountain Formation; Recognized as temperate/subtropical uplands right after the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum and spanning the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum, preserves highly detailed uplands lacustrine fauna and flora. |

| |

| Monte Solane | 51-49 MA | Verona, Italy | Slightly older than the nearby, more well-known Monte Bolca site, the Monte Solane site also preserves numerous marine fish and plants, but documents an entirely different ecosystem that appears to be of a bathypelagic habitat, forming one of the few known lagerstätte to preserve a deep-sea ecosystem.[163] | |

|

50 Ma |

Colorado/Utah/Wyoming, US |

An Eocene aged site that is noted for the fish fauna preserved. Other fossils include the crocodilians, birds, and mammals. |

| |

|

50-49 Ma |

Verona, Italy |

A fossil site with specimens of fish and other organisms that are so highly preserved that their organs are often completely intact in fossil form, and even the skin color can sometimes be determined. It is assumed that mud at the site was low in oxygen, preventing both decay and the mixing action of scavengers from harming the fossils. |

| |

|

47 Ma |

Hessen, Germany |

This site has significant geological and scientific importance. Over 1000 species of plants and animals have been found at the site. After almost becoming a landfill, strong local resistance eventually stopped these plans and the Messel Pit was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site on 9 December 1995. Significant scientific discoveries about the early evolution of mammals and birds are still being made at the Messel Pit, and the site has increasingly become a tourist site as well. |

| |

| Baltic amber | 47-35 Ma (Lutetian to Priabonian) | Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland & Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia | The largest amber deposit on Earth, this amber is part of the Prussian Formation, and preserves a high diversity of exceptionally well-preserved fossil invertebrates, plants, and small vertebrates that inhabited eastern Europe during the warmer, subtropical conditions of the middle Eocene. It is the largest world's single largest repository of fossil insects.[164][165][166][167] |  |

| Kishenehn Formation | 46.2 Ma | Montana | A Middle Eocene site preserving exquisitely detailed insect specimens in oil shale.[168] | |

| Mahenge | 46 Ma | Tanzania | A terrestrial Middle Eocene lagerstätte preserving plant and arthropod fossils.[169][170] | |

|

45-25 Ma |

Occitania, France |

This site qualifies as a lagerstätte because beside a large variety of mammals, birds, turtles, crocodiles, flora and insects, it also preserves the soft tissues of amphibians and squamates, in addition to their articulated skeleton in what has been called natural mummies. |

| |

| Na Duong | Priabonian | Northern Vietnam | A Late Eocene site notable for its highly detailed coprolite preservation.[172] | |

| Bitterfeld amber | 38-34 Ma | Saxony, Germany | One of three major Paleogene deposits of European amber, this deposit of the Cottbus Formation shares a similar biota to the Baltic Amber, indicating a concurrent formation, but appears to have a geologically distinct origin from Baltic amber.[167] |  |

| Rovno amber | 38-34 Ma | Rivne Oblast, Ukraine & Gomel, Belarus | One of three major Paleogene deposits of European amber, this deposit of the Obukhov Formation preserves a high diversity of invertebrates, many of which are shared with the Baltic amber but others of which are unique. A drier habitat compared to the Baltic amber is suggested based on some of the insect taxa preserved.[164] |  |

|

34 Ma |

Colorado, US |

A late Eocene (Priabonian) aged site that is noted for the finely preserved plant and insect paleobiota. Fossils are preserved in diatom blooms of a lahar dammed lake system and the formation is noted for the petrified stumps of Sequoia affinis |

| |

| Canyon Ferry Reservoir | 32.0 ± 0.1 Ma | Montana, US | A diverse Early Oligocene plant and insect fossil site.[173] | |

| Rauenberg | 30 Ma | Baden-Württemberg, Germany | A marine fossil site with an Arctic-like invertebrate fauna and a Paratethyan vertebrate fauna displaying evidence of intermittent anoxia.[174] | |

| Sangtang Lagerstätte | ~28 – 23 Ma | Guangxi, China | A section of the Late Oligocene Yongning Formation with one of the very few known Cenozoic assemblages of mummified plant fossils,[175] including mummified fruits.[176][177][178] | |

|

Enspel Lagerstätte |

24.79-24.56 Ma |

Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany |

||

| Aix-en-Provence | ~24 Ma | Provence, France | A terminal Oligocene brackish palaeoenvironment.[180] |

Neogene

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominican amber | 30–10 Ma | Dominican Republic | Dominican amber differentiates itself from Baltic amber by being nearly always[citation needed] transparent, and it has a higher number of fossil inclusions. This has enabled the detailed reconstruction of the ecosystem of a long-vanished tropical forest.[181] |  |

| Riversleigh | 25–15 Ma | Queensland, Australia | This locality is recognised for the series of well preserved fossils deposited from the Late Oligocene to the Miocene. The fossiliferous limestone system is located near the Gregory River in the north-west of Queensland, an environment that was once a very wet rainforest that became more arid as the Gondwanan land masses separated and the Australian continent moved north. |  |

| Foulden Maar | 23 Ma | Otago, New Zealand | These layers of diatomite have preserved exceptional fossils of fish from the crater lake, and plants, spiders, and insects from the sub-tropical forest that developed around the crater,[182] along with in situ pollen.[183] |  |

| Ebelsberg Formation | 23-22 Ma | Upper Austria, Austria | This Aquitanian-aged konservat-lagerstätte records an exceptional fossil assemblage of an enormous number of plants, fish, marine mammals, and marine invertebrates from a section of the central Paratethys Sea.[184] |  |

| Chiapas amber | 23-15 Ma | Chiapas, Mexico[185] | As with other ambers, a wide variety of taxa have been found as inclusions including insects and other arthropods, as well as plant fragments and epiphyllous fungi. |  |

| Clarkia fossil beds | 20-17 Ma | Idaho, US | The Clarkia fossil beds site is best known for its fossil leaves. Their preservation is exquisite; fresh leaves are unfossilized, and sometimes retain their fall colors before rapidly oxidizing in air. It has been reported that scientists have managed to isolate small amounts of ancient DNA from fossil leaves from this site. However, other scientists are skeptical of the validity of this reported occurrence of Miocene DNA. |  |

| Barstow Formation | 19–13.4 Ma | California, US | The sediments are fluvial and lacustrine in origin except for nine layers of rhyolitic tuff. It is well known for its abundant vertebrate fossils including bones, teeth and footprints. The formation is also renowned for the fossiliferous concretions in its upper member, which contain three-dimensionally preserved arthropods. |  |

| Shanwang Formation | 18-17 Ma | Shandong Province, China | Fossils have been found at this site in dozens of categories, representing over 600 separate species. Animal fossils include insects, fish, spiders, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Insect fossils have clear, intact veins. Some have retained beautiful colours. |  |

| Morozaki Group[186] | 18-17 Ma | Aichi Prefecture, Japan | Known from well-preserved deep sea fauna including fish, starfish and arthropods like crabs, shrimps and giant amphiopods. | |

| Sandelzhausen | 16 Ma | Bavaria, Germany | A Middle Miocene vertebrate locality.[187] | |

| McGraths Flat | ~16-11 Ma | NSW, Australia | Deposited in unusual conditions that record microscopic details of soft tissues and delicate structures. Fossil evidence of animals with soft bodies, unlike the bones of mammals and reptiles, is rare in Australia, and discoveries at McGraths' Flat have revealed unknown species of invertebrates such as insects and spiders.[188] | |

| Dolnja Stara | ~15 Ma | Slovenia | A barnacle fossil site preserving barnacles shortly after settlement attached to mangrove leaves.[189] | |

| Pisco Formation | 15-2 Ma | Arequipa & Ica, Peru | Several specialists consider the Pisco Formation one of the most important lagerstätten, based on the large amount of exceptionally preserved marine fossils, including sharks (most notably megalodon), penguins, whales, dolphins, birds, marine crocodiles and aquatic giant sloths. |  |

| Hindon Maar | 14.6 Ma | New Zealand | A maar preserving a Southern Hemisphere lake-forest ecosystem, including body fossils of plants, insects, fish, and birds,[190] along with in situ pollen[183] and coprolites of both fish and birds.[190] | |

| Ngorora Formation | 13.3-9 Ma | Tanzania | The alkaline palaeolake deposits of the Ngorora Formation contains articulated fish fossils that died en masse from asphyxiation during episodic ash falls or from rapid acidification.[191] |  |

| Pi Gros | 13 Ma | Catalonia, Spain | An ichnofossil lagerstätte containing annelid, mollusc, and sponge trace fossils. The fossil site no longer exists due to having been quarried for the construction of an industrial park.[192] | |

| Bullock Creek | 12 Ma | Northern Territory, Australia | Among the fossils at the Bullock Creek site have been found complete marsupial crania with delicate structures intact. New significant taxa identified from the Bullock Creek mid Miocene include a new genus of crocodile, Baru (Baru darrowi), a primitive true kangaroo, Nambaroo, with high-crowned lophodont teeth; and a new species of giant horned tortoise, Meiolania. New marsupial lion, thylacine, and dasyurid material has also been recovered. | |

| Tunjice | ? (Middle Miocene) | Slovenia | This site is known worldwide for the earliest fossil records of seahorses.[193] |  |

| Ashfall Fossil Beds | 11.83 Ma | Nebraska, US | The Ashfall Fossil Beds of Antelope County in northeastern Nebraska are rare fossil sites of the type called lagerstätten that, due to extraordinary local conditions, capture an ecological "snapshot" in time of a range of well-preserved fossilized organisms. Ash from a Yellowstone hotspot eruption 10-12 million years ago created these fossilized bone beds. |  |

| Alcoota Fossil Beds | 8 Ma | Northern Territory, Australia | It is notable for the occurrence of well-preserved, rare, Miocene vertebrate fossils, which provide evidence of the evolution of the Northern Territory's fauna and climate. The Alcoota Fossil Beds are also significant as a research and teaching site for palaeontology students. |  |

| Saint-Bauzile | 7.6-7.2 Ma | Ardèche, France | A Late Miocene site preserving articulated mammal skeletons with skin and fur impressions.[194] | |

| Capo San Marco Formation | ~7 Ma | Sardinia, Italy | A microbialite containing exceptionally preserved Girvanella-type filaments.[195] | |

| Tresjuncos | 6 Ma | Cuenca, Spain | A Late Miocene lacustrine konservat-lagerstätte containing fossils of diatoms, plants, crustaceans, insects, and amphibians.[196] | |

| Gray Fossil Site | 4.9-4.5 Ma | Tennessee, US | As the first site of its age known from the Appalachian region, the Gray Fossil Site is a unique window into the past. Research at the site has yielded many surprising discoveries, including new species of red panda, rhinoceros, pond turtle, hickory tree, and more. The site also hosts the world's largest known assemblage of fossil tapirs. |  |

| Willershausen | Late Pliocene | Lower Saxony, Germany | A lacustrine fossil site containing well preserved beetles.[197] |

Quaternary

[edit]| Site(s) | Age | Location | Significance | Notable fossils/organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Mammoth Site | 26 Ka | South Dakota, US | The facility encloses a prehistoric sinkhole that formed and was slowly filled with sediments during the Pleistocene era. As of 2016, the remains of 61 mammoths, including 58 North American Columbian and 3 woolly mammoths had been recovered. Mammoth bones were found at the site in 1974, and a museum and building enclosing the site were established. |  |

| Rancho La Brea Tar Pits | 40–12 Ka | California, US | A group of tar pits where natural asphalt (also called asphaltum, bitumen, or pitch; brea in Spanish) has seeped up from the ground for tens of thousands of years. Over many centuries, the bones of trapped animals have been preserved. Among the prehistoric species associated with the La Brea Tar Pits are Pleistocene mammoths, dire wolves, short-faced bears, American lions, ground sloths, and, the state fossil of California, the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis). |  |

| Waco Mammoth National Monument | 65–51 Ka | Texas, US | A paleontological site and museum in Waco, Texas, United States where fossils of 24 Columbian mammoths (Mammuthus columbi) and other mammals from the Pleistocene Epoch have been uncovered. The site is the largest known concentration of mammoths dying from a (possibly) reoccurring event, which is believed to have been a flash flood. |  |

| El Breal de Orocual | 2.5–1 Ma | Monagas, Venezuela | The largest asphalt well on the planet. Like the La Brea Tar Pits, this site preserves a number of megafauna like toxodonts, glyptodonts, camelids, and the felid Homotherium venezuelensis. |  |

| El Mene de Inciarte | 28–25.5 Ka | Zulia, Venezuela | Another series of tar pits. These also preserve a similar assemblage of megafauna. | |

| Naracoorte Caves | 500-1 Ka | South Australia, Australia | A series of caves that preserve numerous pleistocene megafauna, like Thylacoleo, and is recognized as a World heritage site alongside the older, but geographically similar Riversleigh site. |  |

| Mare aux Songes | 4 Ka | Mauritius | A marsh that preserves a diversity of subfossil animals and plants, many of which were driven to extinction without proper documentation following human arrival, most notably the famous dodo. The mortality assemblages may have formed from a freshwater lake that was occasionally impacted by catastrophic droughts.[198] |  |

| Crawford Lake | 800 Ya-present | Ontario, Canada | This lake is notable for its detailed preservation of rotifer and dinoflagellate fossils even after centuries, documenting the ecological shifts that occurred in and around the lake following the establishment of a Iroquoian village from 1268–1486 CE, and later following European colonization of the region in the early 19th century.[199] |

See also

[edit]- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- Hoard, a concentration of human artifacts useful for similar reasons in archaeology

References

[edit]- ^ The term was originally coined by Adolf Seilacher in: Seilacher, A. (1970). "Begriff und Bedeutung der Fossil-Lagerstätten: Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paläontologie". Monatshefte (in German). 1970: 34–39.

- ^ The term was redefined by Julien Kimmig and James D. Schiffbauer in: Kimmig, Julien; James D. Schiffbauer (25 April 2024). "A modern definition of Fossil-Lagerstätten". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 39 (6): 621–624. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2024.04.004. PMID 38670863.

- ^ Briggs et al. 1983; Aldridge et al. 1993.[full citation needed]

- ^ Retallack, G. J. (2011). "Exceptional fossil preservation during CO2 greenhouse crises?". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 307 (1–4): 59–74. Bibcode:2011PPP...307...59R. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.04.023.

- ^ a b Kimmig, Julien; Schiffbauer, James D. (2024). "A modern definition of Fossil-Lagerstätten". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 39 (7): 621–624. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2024.04.004. PMID 38670863.

- ^ Slotznick, Sarah P.; Swanson-Hysell, Nicholas L.; Zhang, Yiming; Clayton, Katherine E.; Wellman, Charles H.; Tosca, Nicholas J.; Strother, Paul K. (22 August 2023). "Reconstructing the paleoenvironment of an oxygenated Mesoproterozoic shoreline and its record of life". Geological Society of America Bulletin. doi:10.1130/B36634.1. ISSN 0016-7606. Retrieved 21 May 2024 – via GeoScienceWorld.

- ^ Strother, Paul K.; Wellman, Charles H. (30 November 2020). "The Nonesuch Formation Lagerstätte: a rare window into freshwater life one billion years ago". Journal of the Geological Society. 178 (2): 1–12. doi:10.1144/jgs2020-133. S2CID 229003508.

- ^ Duda, Jan-Peter; König, Hannah; Reinhardt, Manuel; Shuvalova, Julia; Parkhaev, Pavel (8 December 2021). "Molecular fossils within bitumens and kerogens from the ~ 1 Ga Lakhanda Lagerstätte (Siberia, Russia) and their significance for understanding early eukaryote evolution". PalZ. 95 (4): 577–592. doi:10.1007/s12542-021-00593-4. ISSN 0031-0220.

- ^ Shuvalova, J. V.; Nagovitsin, K. E.; Parkhaev, P. Yu. (26 February 2021). "Evidences of the Oldest Trophic Interactions in the Riphean Biota (Lakhanda Lagerstätte, Southeastern Siberia)". Doklady Biological Sciences. 496 (1): 34–40. doi:10.1134/S0012496621010105. PMID 33635488. S2CID 254411264. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Podkovyrov, Victor N. (September 2009). "Mesoproterozoic Lakhanda Lagerstätte, Siberia: Paleoecology and taphonomy of the microbiota". Precambrian Research. 173 (1–4): 146–153. Bibcode:2009PreR..173..146P. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2009.04.006. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Turnbull, Matthew J. M.; Whitehouse, Martin J.; Moorbath, Stephen (November 1996). "New isotopic age determinations for the Torridonian, NW Scotland". Journal of the Geological Society. 153 (6): 955–964. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.153.6.0955. ISSN 0016-7649. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Battison, Leila; Brasier, Martin D. (February 2012). "Remarkably preserved prokaryote and eukaryote microfossils within 1Ga-old lake phosphates of the Torridon Group, NW Scotland". Precambrian Research. 196–197: 204–217. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2011.12.012. Retrieved 7 July 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Nielson, Grace C.; Stüeken, Eva E.; Prave, Anthony R. (February 2024). "Estuaries house Earth's oldest known non-marine eukaryotes". Precambrian Research. 401: 107278. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2023.107278. hdl:10023/28949. Retrieved 21 May 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Maloney, Katie M.; Schiffbauer, James D.; Halverson, Galen P.; Xiao, Shuhai; Laflamme, Marc (13 April 2022). "Preservation of early Tonian macroalgal fossils from the Dolores Creek Formation, Yukon". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 6222. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.6222M. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-10223-x. PMC 9007953. PMID 35418588.

- ^ Sergeev, Vladimir N.; Schopf, J. William (1 May 2010). "Taxonomy, paleoecology and biostratigraphy of the late Neoproterozoic Chichkan microbiota of South Kazakhstan: The marine biosphere on the eve of metazoan radiation". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (3): 363–401. Bibcode:2010JPal...84..363S. doi:10.1666/09-133.1. S2CID 140668863. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Willman, Sebastian; Peel, John S.; Ineson, Jon R.; Schovsbo, Niels H.; Rugen, Elias J.; Frei, Robert (6 November 2020). "Ediacaran Doushantuo-type biota discovered in Laurentia". Communications Biology. 3 (1): 647. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-01381-7. PMC 7648037. PMID 33159138.

- ^ Becker-Kerber, Bruno; El Albani, Abderrazak; Konhauser, Kurt; Abd Elmola, Ahmed; Fontaine, Claude; Paim, Paulo S. G.; Mazurier, Arnaud; Prado, Gustavo M. E. M.; Galante, Douglas; Kerber, Pedro B.; da Rosa, Ana L. Z.; Fairchild, Thomas R.; Meunier, Alain; Pacheco, Mírian L. A. F. (3 March 2021). "The role of volcanic-derived clays in the preservation of Ediacaran biota from the Itajaí Basin (ca. 563 Ma, Brazil)". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 5013. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-84433-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7930025. PMID 33658558.

- ^ Xiao, Shuhai; Chen, Zhe; Pang, Ke; Zhou, Chuanming; Yuan, Xunlai (12 October 2020). "The Shibantan Lagerstätte: insights into the Proterozoic–Phanerozoic transition". Journal of the Geological Society. 178: 1–11. doi:10.1144/jgs2020-135. S2CID 225242787. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Cai, Yaoping; Hua, Hong; Schiffbauer, James D.; Sun, Bo; Yuan, Xunlai (April 2014). "Tube growth patterns and microbial mat-related lifestyles in the Ediacaran fossil Cloudina, Gaojiashan Lagerstätte, South China". Gondwana Research. 25 (3): 1008–1018. Bibcode:2014GondR..25.1008C. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2012.12.027. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Feng, Tang; Chongyu, Yin; Pengju, Liu; Linzhi, Gao; Wenyan, Zhang (7 September 2010). "A New Diverse Macrofossil Lagerstätte from the Uppermost Ediacaran of Southwestern China". Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition. 82 (6): 1095–1103. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2008.tb00709.x. ISSN 1000-9515. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ Duda, Jan-Peter; Love, Gordon D.; Rogov, Vladimir I.; Melnyk, Dmitry S.; Blumenberg, Martin; Grazhdankin, Dmitriy V. (3 September 2020). "Understanding the geobiology of the terminal Ediacaran Khatyspyt Lagerstätte (Arctic Siberia, Russia)". Geobiology. 18 (6): 643–662. Bibcode:2020Gbio...18..643D. doi:10.1111/gbi.12412. PMID 32881267. S2CID 221477265.

- ^ National Museum of Natural History, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (Kyiv, Ukraine); Grytsenko, Volodymyr (2 October 2020). "Diversity of the Vendian fossils of Podillia (Western Ukraine)". Geo&Bio. 2020 (19): 3–19. doi:10.15407/gb1903.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shao, Tiequan; Tang, Hanhua; Liu, Yunhuan; Waloszek, Dieter; Maas, Andreas; Zhang, Huaqiao (March 2018). "Diversity of cnidarians and cycloneuralians in the Fortunian (early Cambrian) Kuanchuanpu Formation at Zhangjiagou, South China". Journal of Paleontology. 92 (2): 115–129. doi:10.1017/jpa.2017.94. ISSN 0022-3360. Retrieved 14 May 2024 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^ Shao, T. Q.; Qin, J. C.; Shao, Y.; Liu, Y. H.; Waloszek, D.; Maas, A.; Duan, B. C.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H. Q. (October 2020). "New macrobenthic cycloneuralians from the Fortunian (lowermost Cambrian) of South China". Precambrian Research. 349: 105413. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2019.105413. Retrieved 14 May 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Liu, Yunhuan; Qin, Jiachen; Wang, Qi; Maas, Andreas; Duan, Baichuan; Zhang, Yanan; Zhang, Hu; Shao, Tiequan; Zhang, Huaqiao (19 October 2018). Zhang, Xi-Guang (ed.). "New armoured scalidophorans (Ecdysozoa, Cycloneuralia) from the Cambrian Fortunian Zhangjiagou Lagerstätte, South China". Papers in Palaeontology. 5 (2): 241–260. doi:10.1002/spp2.1239. ISSN 2056-2799. Retrieved 14 May 2024 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ Han, Jian; Morris, Simon Conway; Ou, Qiang; Shu, Degan; Huang, Hai (9 February 2017). "Meiofaunal deuterostomes from the basal Cambrian of Shaanxi (China)". Nature. 542 (7640): 228–231. doi:10.1038/nature21072. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28135722. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Lan, Tian; Yang, Jie; Zhang, Xi-guang; Hou, Jin-bo (15 June 2018). "A new macroalgal assemblage from the Xiaoshiba Biota (Cambrian Series 2, Stage 3) of southern China". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 499: 35–44. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.02.029. ISSN 0031-0182. Retrieved 13 September 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ English, Adam M.; Babcock, Loren E. (1 September 2010). "Census of the Indian Springs Lagerstätte, Poleta Formation (Cambrian), western Nevada, USA". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 295 (1): 236–244. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.05.041. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Ivantsov, Andrey Yu.; Zhuravlev, Andrey Yu.; Leguta, Anton V.; Krassilov, Valentin A.; Melnikova, Lyudmila M.; Ushatinskaya, Galina T. (2 May 2005). "Palaeoecology of the Early Cambrian Sinsk biota from the Siberian Platform". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 220 (1–2): 69–88. Bibcode:2005PPP...220...69I. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.01.022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Caron, Jean-Bernard; Webster, Mark; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Pari, Giovanni; Santucci, Guy; Mángano, M. Gabriela; Izquierdo-López, Alejandro; Streng, Michael; Gaines, Robert R. (13 December 2023). "The lower Cambrian Cranbrook Lagerstätte of British Columbia". Journal of the Geological Society. 181 (1). doi:10.1144/jgs2023-106. ISSN 0016-7649. Retrieved 7 July 2024 – via Lyell Collection Geological Society Publications.

- ^ Weisberger, Mindy (9 July 2024). "'Prehistoric Pompeii' reveals 515 million-year-old sea bugs' anatomy in pristine 3D". CNN. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Pari, Giovanni; Briggs, Derek E.G.; Gaines, Robert R. (22 February 2021). "The Parker Quarry Lagerstätte of Vermont—The first reported Burgess Shale–type fauna rediscovered". Geology. 49 (6): 693–697. doi:10.1130/g48422.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ Gámez Vintaned, J. A.; Liñán, E. y Gozalo, R. (2013) «Los trilobites cámbricos de la Biota de Murero (Zaragoza, España)». Cuadernos de Paleontología Aragonesa, 7: 5-27

- ^ Department of Earth Sciences (Palaeobiology), Uppsala University, Sweden.; Peel, John S. (7 June 2023). "A phosphatised fossil Lagerstätte from the middle Cambrian (Wuliuan Stage) of North Greenland (Laurentia)". Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark. 72: 101–122. doi:10.37570/bgsd-2023-72-03. Retrieved 7 July 2024.