Greco-Buddhism

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

Greco-Buddhism, sometimes spelled Graeco-Buddhism, refers to the cultural syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism, which developed between the 4th century BCE and the 5th century CE in the Indian subcontinent, especially in modern Afghanistan, Pakistan and north-western border regions of modern India. It was a cultural consequence of a long chain of interactions begun by Greek forays into India from the time of Alexander the Great, carried further by the establishment of the Indo-Greek Kingdom and extended during the flourishing of the Hellenized Kushan Empire.[citation needed] Greco-Buddhism influenced the artistic, and perhaps the spiritual development of Buddhism, particularly Mahayana Buddhism.[1] Buddhism was then adopted in Central and Northeastern Asia from the 1st century CE, ultimately spreading to China, Korea, Japan, Philippines, Siberia, and Vietnam.

Historical outline

The interaction between Hellenistic Greece and Buddhism started when Alexander the Great conquered the Achaemenid Empire and further regions of Central Asia in 334 BCE, crossing the Indus River and then the Jhelum after the Battle of the Hydaspes and going as far as the Beas, thus establishing direct contact with India.

Alexander founded several cities in his new territories in the areas of the Amu Darya and Bactria, and Greek settlements further extended to the Khyber Pass, Gandhara (see Taxila), and the Punjab region. These regions correspond to a unique geographical passageway between the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush mountains through which most of the interaction between India and Central Asia took place, generating intense cultural exchange and trade.

Following Alexander's death on June 10, 323 BCE, the Diadochi or "Successors" founded their own kingdoms in Anatolia and Central Asia. General Seleucus set up the Seleucid Empire, which extended as far as India. Later, the eastern part of the Seleucid Kingdom broke away to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (3rd–2nd century BCE), followed by the Indo-Greek Kingdom (2nd–1st century BCE), and later the Kushan Empire (1st–3rd century CE).

The interaction of Greek and Buddhist cultures operated over several centuries until it ended in the 5th century CE with the invasions of the Hephthalite Empire and later the expansion of Islam.

Religious interactions

The length of the Greek presence in Central Asia and northern India provided opportunities for interaction, not only on the artistic, but also on the religious plane.

Alexander the Great in Bactria and India (331–325 BCE)

Obv: Alexander being crowned by Nike.

Rev: Alexander attacking King Porus on his elephant.

Silver. British Museum.

When Alexander invaded Bactria and Gandhara, these areas may already have been under śramānic influence, likely specifically Buddhist and Jain. According to a legend preserved in the Pāli Canon, two merchant brothers from Kamsabhoga in Bactria, Tapassu and Bhallika, visited Gautama Buddha and became his disciples. The legend states that they then returned home and spread the Buddha's teaching.[2]

In 326 BCE, Alexander conquered Northern region of India. King Ambhi of Taxila, known as Taxiles, surrendered his city, a notable Buddhist center, to Alexander. Alexander fought an epic battle against King Porus of Pauravas in the Punjab, at the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BCE.

Several philosophers, such as Pyrrho, Anaxarchus and Onesicritus, are said to have been selected by Alexander to accompany him in his eastern campaigns. During the 18 months they were in India, they were able to interact with Indian ascetics, generally described as Gymnosophists ("naked philosophers"). Pyrrho (360-270 BCE) returned to Greece and became the first Skeptic and the founder of the school named Pyrrhonism. The Greek biographer Diogenes Laërtius explained that Pyrrho's equanimity and detachment from the world were acquired in India.[3] Few of his sayings are directly known, but they are clearly reminiscent of sramanic, possibly Buddhist, thought: "Nothing really exists, but human life is governed by convention. ... Nothing is in itself more this than that"[4]

Another of these philosophers, Onesicritus, a Cynic, is said by Strabo to have learnt in India the following precepts: "That nothing that happens to a man is bad or good, opinions being merely dreams. ... That the best philosophy [is] that which liberates the mind from [both] pleasure and grief"[5])

The Mauryan empire (322–183 BCE)

The Indian emperor Chandragupta, founder of the Mauryan dynasty, re-conquered around 322 BCE the northwest Indian territory that had been lost to Alexander the Great. However, contacts were kept with his Greco-Iranian neighbours in the Seleucid Empire. Seleucid king Seleucus I came to a marital agreement as part of a peace treaty, and several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes, resided at the Mauryan court.

"Chandragupta marched on Magadha with a largely Persian army to win the throne and having overthrown his kinsmen, the last Nanda, with this Persian host of his, he then proceeds to build himself palaces directly modelled on Persepolis. He fills these palaces with images of foreign types and decorates them with Persian fashion. He organizes the court along purely Persian lines, and pays regard to Persian ceremonial down to the washing of his royal hair. the script he introduces is of Achemenid origin; the inscriptions of his grandson still imitate Darius's. His very masons are imported Persians for whom the monarch has such marked regard that he ordains a special set of penalties for all who injure them, while they link the name of Ahura Mazda with the Mauryan palaces that it still echoes down the ages to our day as the Asura Maya." from D.B. Spooner (Director-General of Archeology in India), p. 417. The Zoroasterian Period of Indian History.

Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka embraced the Buddhist faith and became a great proselytizer in the line of the traditional Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism, insisting on non-violence to humans and animals (ahimsa), and general precepts regulating the life of lay people.

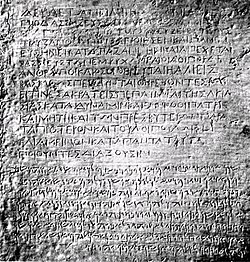

According to the Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek [6] and some in Achemenid script, he sent Buddhist emissaries to the Greek lands in Asia and as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts name each of the rulers of the Hellenic world at the time:

- "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (4,000 miles) away, where the Greek king Antiochos (Antiyoga) rules, and beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy (Turamaya), Antigonos (Antikini), Magas (Maka) and Alexander (Alikasu[n]dara) rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni." (Rock Edict Nb.13[7]).

Ashoka also claims he converted to Buddhism Greek populations within his realm:

- "Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dharma." Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika).

Finally, some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as the famous Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek ("Yona") Buddhist monks, active in Buddhist proselytism (the Mahavamsa, XII[8]).

The Greek presence in Bactria (325 to 125 BCE)

Alexander had established in Bactria several cities (Ai-Khanoum, Begram) and an administration that were to last more than two centuries under the Seleucids and the Greco-Bactrians, all the time in direct contact with Indian territory. The Greeks sent ambassadors to the court of the Mauryan empire, such as the historian Megasthenes under Chandragupta Maurya, and later Deimakos under his son Bindusara, who reported extensively on the civilization of the Indians. Megasthenes sent detailed reports on Indian religions, which were circulated and quoted throughout the Classical world for centuries:[9]

- "Megasthenes makes a different division of the philosophers, saying that they are of two kinds, one of which he calls the Brachmanes, and the other the Sarmanes..." Strabo XV. 1. 58-60[5]

The Greco-Bactrians maintained a strong Hellenistic culture at the door of India during the rule of the Mauryan empire in India, as exemplified by the archaeological site of Ai-Khanoum. When the Mauryan empire was toppled by the Sungas around 180 BCE, the Greco-Bactrians expanded into India, where they established the Indo-Greek kingdom, under which Buddhism was able to flourish.

The Indo-Greek kingdom and Buddhism (180 BCE –10 CE)

The Greco-Bactrians conquered parts of northern India from 180 BCE, whence they are known as the Indo-Greeks. They controlled various areas of the northern Indian territory until 10 CE.

Buddhism prospered under the Indo-Greek kings, and it has been suggested that their invasion of India was intended to protect the Buddhist faith from the religious persecutions of the new Indian dynasty of the Sungas (185–73 BCE) which had overthrown the Mauryans. Zarmanochegas (Zarmarus) (Ζαρμανοχηγὰς) was a monk of the Sramana tradition (possibly, but not necessarily a Buddhist) who, according to ancient historians such as Strabo, Dio Cassius and Nicholas of Damascus traveled to Antioch and Athens while Augustus (died 14 CE) was ruling the Roman Emprire.[10][11]

Coinage

The coins of the Indo-Greek king Menander (reigned 160 to 135 BCE), found from Afghanistan to central India, bear the inscription "Saviour King Menander" in Greek on the front. Several Indo-Greek kings after Menander, such as Zoilos I, Strato I, Heliokles II, Theophilos, Peukolaos, Menander II and Archebios display on their coins the title of "Maharajasa Dharmika" (lit. "King of the Dharma") in the Prakrit language and in the Kharoshthi script.

Some of the coins of Menander I and Menander II incorporate the Buddhist symbol of the eight-spoked wheel, associated with the Greek symbols of victory, either the palm of victory, or the victory wreath handed over by the goddess Nike. According to the Milinda Pañha, at the end of his reign Menander I became a Buddhist arhat,[12] a fact also echoed by Plutarch, who explains that his relics were shared and enshrined.[13]

The ubiquitous symbol of the elephant in Indo-Greek coinage may also have been associated with Buddhism, as suggested by the parallel between coins of Antialcidas and Menander II, where the elephant in the coins of Antialcidas holds the same relationship to Zeus and Nike as the Buddhist wheel on the coins of Menander II. When the zoroastrian Indo-Parthians invaded northern India in the 1st century CE, they adopted a large part of the symbolism of Indo-Greek coinage, but refrained from ever using the elephant, suggesting that its meaning was not merely geographical.

Finally, after the reign of Menander I, several Indo-Greek rulers, such as Amyntas Nikator, King Nicias, Peukolaos, Hermaeus, Hippostratos and Menander II, depicted themselves or their Greek deities forming with the right hand a benediction gesture identical to the Buddhist vitarka mudra (thumb and index joined together, with other fingers extended), which in Buddhism signifies the transmission of Buddha's teaching.

Cities

According to Ptolemy, Greek cities were founded by the Greco-Bactrians in northern India. Menander established his capital in Sagala, today's Sialkot in Punjab, one of the centers of the blossoming Buddhist culture (Milinda Panha, Chap. I). A large Greek city built by Demetrius and rebuilt by Menander has been excavated at the archaeological site of Sirkap near Taxila, where Buddhist stupas were standing side-by-side with Hindu and Greek temples, indicating religious tolerance and syncretism.

Scriptures

Evidence of direct religious interaction between Greek and Buddhist thought during the period include the Milinda Panha, a Buddhist discourse in the platonic style, held between king Menander and the Buddhist monk Nagasena.

Also the Mahavamsa (Chap. XXIX[14]) records that during Menander's reign, "a Greek ("Yona") Buddhist head monk" named Mahadharmaraksita (literally translated as 'Great Teacher/Preserver of the Dharma') led 30,000 Buddhist monks from "the Greek city of Alexandria" (possibly Alexandria-of-the-Caucasus, around 150 km north of today's Kabul in Afghanistan), to Sri Lanka for the dedication of a stupa, indicating that Buddhism flourished in Menander's territory and that Greeks took a very active part in it.

Several Buddhist dedications by Greeks in India are recorded, such as that of the Greek meridarch (civil governor of a province) named Theodorus, describing in Kharoshthi how he enshrined relics of the Buddha. The inscriptions were found on a vase inside a stupa, dated to the reign of Menander or one his successors in the 1st century BCE (Tarn, p391):

- "Theudorena meridarkhena pratithavida ime sarira sakamunisa bhagavato bahu-jana-stitiye":

- "The meridarch Theodorus has enshrined relics of Lord Shakyamuni, for the welfare of the mass of the people"

- (Swāt relic vase inscription of the Meridarkh Theodoros[15])

Finally, Buddhist tradition recognizes Menander as one of the great benefactors of the faith, together with Ashoka and Kanishka.

Buddhist manuscripts in cursive Greek have been found in Afghanistan, praising various Buddhas and including mentions of the Mahayana Lokesvara-raja Buddha (λωγοασφαροραζοβοδδο). These manuscripts have been dated later than the 2nd century CE. (Nicholas Sims-Williams, "A Bactrian Buddhist Manuscript").

Some elements of the Mahayana movement may have begun around the 1st century BCE in northwestern India, at the time and place of these interactions. According to most scholars, the main sutras of Mahayana were written after 100 BCE, when sectarian conflicts arose among Nikaya Buddhist sects regarding the humanity or super-humanity of the Buddha and questions of metaphysical essentialism, on which Greek thought may have had some influence: "It may have been a Greek-influenced and Greek-carried form of Buddhism that passed north and east along the Silk Road".[16]

The Kushan empire (1st–3rd century CE)

The Kushans, one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi confederation settled in Bactria since around 125 BCE when they displaced the Greco-Bactrians, invaded the northern parts of Pakistan and India from around 1 CE.

By that time they had already been in contact with Greek culture and the Indo-Greek kingdoms for more than a century. They used the Greek script to write their language, as exemplified by their coins and their adoption of the Greek alphabet. The absorption of Greek historical and mythological culture is suggested by Kushan sculptures representing Dionysiac scenes or even the story of the Trojan horse[17] and it is probable that Greek communities remained under Kushan rule.

The Kushan king Kanishka, who honored Zoroastrian, Greek and Brahmanic deities as well as the Buddha and was famous for his religious syncretism, convened the Fourth Buddhist Council around 100 CE in Kashmir in order to redact the Sarvastivadin canon. Some of Kanishka's coins bear the earliest representations of the Buddha on a coin (around 120 CE), in Hellenistic style and with the word "Boddo" in Greek script.

Kanishka also had the original Gandhari vernacular, or Prakrit, Mahayana Buddhist texts translated into the high literary language of Sanskrit, "a turning point in the evolution of the Buddhist literary canon"[18]

The "Kanishka casket", dated to the first year of Kanishka's reign in 127 CE, was signed by a Greek artist named Agesilas, who oversaw work at Kanishka's stupas (caitya), confirming the direct involvement of Greeks with Buddhist realizations at such a late date.

The new syncretic form of Buddhism expanded fully into Eastern Asia soon after these events. The Kushan monk Lokaksema visited the Han Chinese court at Luoyang in 178 CE, and worked there for ten years to make the first known translations of Mahayana texts into Chinese. The new faith later spread into Korea and Japan, and was itself at the origin of Zen.

Artistic influences

Numerous works of Greco-Buddhist art display the intermixing of Greek and Buddhist influences, around such creation centers as Gandhara. The subject matter of Gandharan art was definitely Buddhist, while most motifs were of Western Asiatic or Hellenistic origin.

The anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha

Although there is still some debate, the first anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha himself are often considered a result of the Greco-Buddhist interaction. Before this innovation, Buddhist art was "aniconic": the Buddha was only represented through his symbols (an empty throne, the Bodhi tree, the Buddha's footprints, the Dharma wheel).

This reluctance towards anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha, and the sophisticated development of aniconic symbols to avoid it (even in narrative scenes where other human figures would appear), seem to be connected to one of the Buddha’s sayings, reported in the Digha Nikaya, that discouraged representations of himself after the extinction of his body.[19]

Probably not feeling bound by these restrictions, and because of "their cult of form, the Greeks were the first to attempt a sculptural representation of the Buddha".[20] [page needed] In many parts of the Ancient World, the Greeks did develop syncretic divinities, that could become a common religious focus for populations with different traditions: a well-known example is the syncretic God Sarapis, introduced by Ptolemy I in Egypt, which combined aspects of Greek and Egyptian Gods. In India as well, it was only natural for the Greeks to create a single common divinity by combining the image of a Greek God-King (The Sun-God Apollo, or possibly the deified founder of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, Demetrius), with the traditional attributes of the Buddha.

Many of the stylistic elements in the representations of the Buddha point to Greek influence: the Greco-Roman toga-like wavy robe covering both shoulders (more exactly, its lighter version, the Greek himation), the contrapposto stance of the upright figures (see: 1st–2nd century Gandhara standing Buddhas[21]), the stylicized Mediterranean curly hair and topknot (ushnisha) apparently derived from the style of the Belvedere Apollo (330 BCE),[22] and the measured quality of the faces, all rendered with strong artistic realism (See: Greek art). A large quantity of sculptures combining Buddhist and purely Hellenistic styles and iconography were excavated at the Gandharan site of Hadda. The 'curly hair' of Buddha is described in the famous list of 32 external characteristics of a Great Being (mahapurusa) that we find all along the Buddhist sutras. The curly hair, with the curls turning to the right is first described in the Pali canon; we find the same description in e.g. the "Dasasahasrika Prajnaparamita".

Greek artists were most probably the authors of these early representations of the Buddha, in particular the standing statues, which display "a realistic treatment of the folds and on some even a hint of modelled volume that characterizes the best Greek work. This is Classical or Hellenistic Greek, not archaizing Greek transmitted by Persia or Bactria, nor distinctively Roman".[23]

The Greek stylistic influence on the representation of the Buddha, through its idealistic realism, also permitted a very accessible, understandable and attractive visualization of the ultimate state of enlightenment described by Buddhism, allowing it reach a wider audience: "One of the distinguishing features of the Gandharan school of art that emerged in north-west India is that it has been clearly influenced by the naturalism of the Classical Greek style. Thus, while these images still convey the inner peace that results from putting the Buddha's doctrine into practice, they also give us an impression of people who walked and talked, etc. and slept much as we do. I feel this is very important. These figures are inspiring because they do not only depict the goal, but also the sense that people like us can achieve it if we try" (His Holiness The 14th Dalai Lama[24])

During the following centuries, this anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha defined the canon of Buddhist art, but progressively evolved to incorporate more Indian and Asian elements.

A Hellenized Buddhist pantheon

Several other Buddhist deities may have been influenced by Greek gods. For example, Herakles with a lion-skin (the protector deity of Demetrius I) "served as an artistic model for Vajrapani, a protector of the Buddha"[25] (See[26]). In Japan, this expression further translated into the wrath-filled and muscular Niō guardian gods of the Buddha, standing today at the entrance of many Buddhist temples.

According to Katsumi Tanabe, professor at Chūō University, Japan (in "Alexander the Great. East-West cultural contact from Greece to Japan"), besides Vajrapani, Greek influence also appears in several other gods of the Mahayana pantheon, such as the Japanese Wind God Fūjin inspired from the Greek Boreas through the Greco-Buddhist Wardo, or the mother deity Hariti[27] inspired by Tyche.

In addition, forms such as garland-bearing cherubs, vine scrolls, and such semi-human creatures as the centaur and triton, are part of the repertory of Hellenistic art introduced by Greco-Roman artists in the service of the Kushan court.

Greco-Buddhism and the rise of the Mahayana

The geographical, cultural and historical context of the rise of Mahayana Buddhism during the 1st century BCE in northwestern India, all point to intense multi-cultural influences. According to Richard Foltz "Key formative influences on the early development of the Mahayana and Pure Land movements, which became so much part of East Asian civilization, are to be sought in Buddhism's earlier encounters along the Silk Road".[28] As Mahayana Buddhism emerged, it received "influences from popular Hindu devotional cults (bhakti), Persian and Greco-Roman theologies which filtered into India from the northwest" (Tom Lowenstein, p63).

Conceptual influences

Mahayana is an inclusive faith characterized by the adoption of new texts, in addition to the traditional Sūtra Piṭaka of the Early Buddhist schools, and a shift in the understanding of Buddhism. It goes beyond the śrāvaka ideal of the release from suffering, and the Nirvāṇa of the arhats, to elevate the Buddha to a God-like status, and to create a pantheon of quasi-divine bodhisattvas devoting themselves to personal excellence, ultimate knowledge and the salvation of humanity. These concepts, together with the sophisticated philosophical system of the Mahayana faith, may have been influenced by the interaction of Greek and Buddhist thought:

The Buddha as an idealized man-god

The Buddha was elevated to a man-god status, represented in idealized human form: "One might regard the classical influence as including the general idea of representing a man-god in this purely human form, which was of course well familiar in the West, and it is very likely that the example of westerners' treatment of their gods was indeed an important factor in the innovation... The Buddha, the man-god, is in many ways far more like a Greek god than any other eastern deity, no less for the narrative cycle of his story and appearance of his standing figure than for his humanity".[29]

The supra-mundane understanding of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas may have been a consequence of the Greek’s tendency to deify their rulers in the wake of Alexander’s reign: "The god-king concept brought by Alexander (...) may have fed into the developing bodhisattva concept, which involved the portrayal of the Buddha in Gandharan art with the face of the sun god, Apollo" (McEvilley, "The Shape of Ancient Thought").

The Bodhisattva as a Universal ideal of excellence

Lamotte (1954) controversially suggests (though countered by Conze (1973) and others) that Greek influence was present in the definition of the Bodhisattva ideal in the oldest Mahayana text, the "Perfection of Wisdom" or prajñā pāramitā literature, that developed between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE. These texts in particular redefine Buddhism around the universal Bodhisattva ideal, and its six central virtues of generosity, morality, patience, effort, meditation and, first and foremost, wisdom.

Philosophical influences

The close association between Greeks and Buddhism probably led to exchanges on the philosophical plane as well. Many of the early Mahayana theories of reality and knowledge can be related to Greek philosophical schools of thought. Mahayana Buddhism has been described as the "form of Buddhism which (regardless of how Hinduized its later forms became) seems to have originated in the Greco-Buddhist communities of India, through a conflation of the Greek Democritean-Sophistic-Skeptical tradition with the rudimentary and unformalized empirical and skeptical elements already present in early Buddhism" (McEvilly, "The Shape of Ancient Thought", p503).

- In the Prajnaparamita, the rejection of the reality of passing phenomena as "empty, false and fleeting" can also be found in Greek Pyrrhonism.[30]

- The perception of ultimate reality was, for the Cynics as well as for the Madhyamakas and Zen teachers after them, only accessible through a non-conceptual and non-verbal approach (Greek Phronesis), which alone allowed to get rid of ordinary conceptions.[31]

- The mental attitude of equanimity and dispassionate outlook in front of events was also characteristic of the Cynics and Stoics, who called it "Apatheia"[32]

- Nagarjuna's dialectic developed in the Madhyamaka can be paralleled to the Greek dialectical tradition.[33]

Cynicism, Madhyamaka and Zen

Numerous parallels exist between the Greek philosophy of the Cynics and, several centuries later, the Buddhist philosophy of the Madhyamika and Zen. The Cynics denied the relevancy of human conventions and opinions (described as typhos, literally "smoke" or "mist", a metaphor[citation needed] for "illusion" or "error"), including verbal expressions, in favor of the raw experience of reality. They stressed the independence from externals to achieve happiness ("Happiness is not pleasure, for which we need external, but virtue, which is complete without external" 3rd epistole of Crates). Similarly the Prajnaparamita, precursor of the Madhyamika, explained that all things are like foam, or bubbles, "empty, false, and fleeting", and that "only the negation of all views can lead to enlightenment" (Nāgārjuna, MK XIII.8). In order to evade the world of illusion, the Cynics recommended the discipline and struggle ("askēsis kai machē") of philosophy, the practice of "autarkia" (self-rule), and a lifestyle exemplified by Diogenes, which, like Buddhist monks, renounced earthly possessions. These conceptions, in combination with the idea of "philanthropia" (universal loving kindness, of which Crates, the student of Diogenes, was the best proponent), are strikingly reminiscent of Buddhist Prajna (wisdom) and Karuṇā (compassion).[34]

Greco-Persian cosmological influences

A popular figure in Greco-Buddhist art, the future Buddha Maitreya, has sometimes been linked to the Iranian yazata (Zoroastrian divinity) Mithra who was also adopted as a figure in a Greco-Roman syncretistic cult under the name of Mithras. Maitreya is the fifth Buddha of the present world-age, who will appear at some undefined future epoch. According to Richard Foltz, he "echoes the qualities of the Zoroastrian Saoshyant and the Christian Messiah".[35] However, in character and function, Maitreya does not much resemble either Mitra, Mithra or Mithras; his name is more obviously derived from the Sanskrit maitrī "kindliness", equivalent to Pali mettā; the Pali (and probably older) form of his name, Metteyya, does not closely resemble the name Miθra.

The Buddha Amitābha (literally meaning "infinite radiance") with his paradisiacal "Pure Land" in the West, according to Foltz, "seems to be understood as the Iranian god of light, equated with the sun". This view is however not in accordance with the view taken of Amitābha by present-day Pure Land Buddhists, in which Amitābha is neither "equated with the sun" nor, strictly speaking, a god.

Gandharan proselytism

Buddhist monks from the region of Gandhara, where Greco-Buddhism was most influential, played a key role in the development and the transmission of Buddhist ideas in the direction of northern Asia.

- Kushan monks, such as Lokaksema (c. 178 CE), travelled to the Chinese capital of Loyang, where they became the first translators of Mahayana Buddhist scriptures into Chinese.[35] Central Asian and East Asian Buddhist monks appear to have maintained strong exchanges until around the 10th century, as indicated by frescos from the Tarim Basin.

- Two half-brothers from Gandhara, Asanga and Vasubandhu (4th century), created the Yogacara or "Mind-only" school of Mahayana Buddhism, which through one of its major texts, the Lankavatara Sutra, became a founding block of Mahayana, and particularly Zen, philosophy.

- In 485 CE, according to the Chinese historic treatise Liang Shu, five monks from Gandhara travelled to the country of Fusang ("The country of the extreme East" beyond the sea, probably eastern Japan, although some historians suggest the American Continent), where they introduced Buddhism:

- "Fusang is located to the east of China, 20,000 li (1,500 kilometers) east of the state of Da Han (itself east of the state of Wa in modern Kyūshū, Japan). (...) In former times, the people of Fusang knew nothing of the Buddhist religion, but in the second year of Da Ming of the Song dynasty (485 CE), five monks from Kipin (Kabul region of Gandhara) travelled by ship to Fusang. They propagated Buddhist doctrine, circulated scriptures and drawings, and advised the people to relinquish worldly attachments. As a results the customs of Fusang changed" (Chinese: "扶桑在大漢國東二萬餘里,地在中國之東(...)其俗舊無佛法,宋大明二年,罽賓國嘗有比丘五人游行至其國,流通佛法,經像,教令出家,風 俗遂改." Liang Shu, 7th century CE).

- Bodhidharma, the founder of Chán-Buddhism which later became Zen, is described as a Central Asian Buddhist monk in the first Chinese references to him (Yan Xuan-Zhi, 547 CE), although later Chinese traditions describe him as coming from South India.

Greco-Buddhism and the West

In the direction of the West, the Greco-Buddhist syncretism may also have had some formative influence on the religions of the Mediterranean Basin.

Exchanges

Intense westward physical exchange at that time along the Silk Road is confirmed by the Roman craze for silk from the 1st century BCE to the point that the Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds. This is attested by at least three significant authors:

- Strabo (64/ 63 BCE–c. 24 CE).

- Seneca the Younger (c. 3 BCE–65 CE).

- Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE).

The aforementioned Strabo and Plutarch (c. 45–125 CE) wrote about king Menander, confirming that information was circulating throughout the Hellenistic world.

Religious influences

Buddhism and Christianity

Although the philosophical systems of Buddhism and Christianity have evolved in rather different ways, the moral precepts advocated by Buddhism from the time of Ashoka through his edicts do have some similarities with the Christian moral precepts developed more than two centuries later: respect for life, respect for the weak, rejection of violence, pardon to sinners, tolerance.

One theory is that these similarities may indicate the propagation of Buddhist ideals into the Western World, with the Greeks acting as intermediaries and religious syncretists.[36]

- "Scholars have often considered the possibility that Buddhism influenced the early development of Christianity. They have drawn attention to many parallels concerning the births, lives, doctrines, and deaths of the Buddha and Jesus" (Bentley, "Old World Encounters").

The story of the birth of the Buddha was well known in the West, and possibly influenced the story of the birth of Jesus: Saint Jerome (4th century CE) mentions the birth of the Buddha, who he says "was born from the side of a virgin".[37]

See also

- Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

- Indo-Greek Kingdom

- Greco-Buddhist Art

- Religions of the Indo-Greeks

- Buddhas of Bamyan

- Kushan Empire

- Mathura

References

- Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, 2nd edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010 ISBN 978-062-125-1

- The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity by John Boardman (Princeton University Press, 1994) ISBN 0-691-03680-2

- The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies by Thomas McEvilley (Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts, 2002) ISBN 1-58115-203-5

- Old World Encounters: Cross-cultural contacts and exchanges in pre-modern times by Jerry H.Bentley (Oxford University Press, 1993) ISBN 0-19-507639-7

- Alexander the Great: East-West Cultural contacts from Greece to Japan (NHK and Tokyo National Museum, 2003)

- Living Zen by Robert Linssen (Grove Press New York, 1958) ISBN 0-8021-3136-0

- Echoes of Alexander the Great: Silk route portraits from Gandhara by Marian Wenzel, with a foreword by the Dalai Lama (Eklisa Anstalt, 2000) ISBN 1-58886-014-0

- "When the Greeks Converted the Buddha: Asymmetrical Transfers of Knowledge in Indo-Greek Cultures" by Georgios T. Halkias, In Trade and Religions: Religious Formation, Transformation and Cross-Cultural Exchange between East and West, ed. Volker Rabens. Brill Publishers, 2013: 65-115.

- The Edicts of King Asoka: An English Rendering by Ven. S. Dhammika (The Wheel Publication No. 386/387) ISBN 955-24-0104-6

- Mahayana Buddhism, The Doctrinal Foundations, Paul Williams, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-02537-0

- The Greeks in Bactria and India, W.W. Tarn, South Asia Books, ISBN 81-215-0220-9

- Lowenstein, Tom (1996). The vision of the Buddha. Duncan Baird Publishers. ISBN 1-903296-91-9.

Notes

- ^ "Greek as well as Iranian influences appear to have shaped the evolution of Mahayana images (and perhaps thought as well)". Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010, p. 46 ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- ^ Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, p. 43

- ^ "He would withdraw from the world and live in solitude, rarely showing himself to his relatives; this is because he had heard an Indian reproach Anaxarchus, telling him that he would never be able to teach others what is good while he himself danced attendance on kings in their court. He would maintain the same composure at all times." (Diogenes Laertius, IX.63 on Pyrrhon)

- ^ (Diogenes Laërtius IX.61

- ^ a b Strabo, XV.I.65: "Strabo XV.1". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

- ^ For an English translation of the Greek edicts see Halkias, Georgios “When the Greeks Converted the Buddha: Asymmetrical Transfers of Knowledge in Indo-Greek Cultures.” In Trade and Religions: Religious Formation, Transformation and Cross-Cultural Exchange between East and West, ed. Volker Rabens. Brill Publishers, 2013: 65-115.

- ^ Full text of the Edicts of Ashoka. See Rock Edict 13

- ^ Full text of the Mahavamsa Click chapter XII

- ^ Surviving fragments of Megasthenes:Full text

- ^ Strabo, xv, 1, on the immolation of the Sramana in Athens (Paragraph 73).

- ^ Dio Cassius, liv, 9.

- ^ Extract of the Milinda Panha: "And afterwards, taking delight in the wisdom of the Elder, he handed over his kingdom to his son, and abandoning the household life for the houseless state, grew great in insight, and himself attained to Arahatship!" (The Questions of King Milinda, Translation by T. W. Rhys Davids, 1890)

- ^ Plutarch on Menander: "But when one Menander, who had reigned graciously over the Bactrians, died afterwards in the camp, the cities indeed by common consent celebrated his funerals; but coming to a contest about his relics, they were difficultly at last brought to this agreement, that his ashes being distributed, everyone should carry away an equal share, and they should all erect monuments to him." (Plutarch, "Political Precepts" Praec. reip. ger. 28, 6) p147–148 Full text

- ^ Full text of the Mahavamsa Click chapter XXIX

- ^ Full text of Theodoros in Gandhari script Text

- ^ McEvilly, "The shape of ancient thought".

- ^ Image of the Indianized Trojan horse story: Kushan Trojan horse

- ^ Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, p. 45

- ^ "Due to the statement of the Master in the Dighanikaya disfavouring his representation in human form after the extinction of body, reluctance prevailed for some time". Also "Hinayanis opposed image worship of the Master due to canonical restrictions". R.C. Sharma, in "The Art of Mathura, India", Tokyo National Museum 2002, p.11

- ^ Linssen, "Zen Living"

- ^ Standing Buddhas: Image 1, Image 2

- ^ The Belvedere Apollo: Image

- ^ Boardman

- ^ The Dalai Lama, foreword to "Echoes of Alexander the Great", 2000.

- ^ Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, p. 44

- ^ Images of the Herakles-influenced Vajrapani: Image 1, Image 2

- ^ Images of the evolution of Hariti: Kariteimo and Kishibojin in Japan.

- ^ Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, p. 9

- ^ Boardman, "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity", p126

- ^ "The most famous, the Heart Sutra, says: "There is no form, nor feeling, nor perception, nor impulse, nor consciousness, no eye, or ear, or nose, or tongue, or body, or mind, no form, nor sound, nor smell, nor taste, or touchable, nor object of mind...". It is worth noting that there are Greek texts that speak in a very similar voice, for example the following (probably Pyrrhonist) statement which is quoted by a commentator on Plato's Theatetus: "No form, no words, no object of taste, or smell, or touch, no other object of perception, has any distinctive character"" (Mc Evilley, "The shape of ancient thought", p419)

- ^ "For the Cynics, as for Madhyamakas, Zen teachers, and others, phenomena could be dealt with legitimately only in a nonverbal and nonconceptual cognition (phronesis) the same word Plato used for "unhypothesized knowledge"), which can result only from the ultimate elenchus of stripping the mind of all the conceptions with which it ordinarily tries to deal with them" (Mc Evilley, "The shape of ancient thought", p439)

- ^ "The ethics of both the methaphysical and the critical branches of the Greek tradition involves withdrawal from passionate belief and the development of equanimity" (Mc Evilley, "The shape of ancient thought", p420) "Cynic sages, like Buddhist monks, renounced home and possessions and to the streets as wanderers and temple beggars. The closely related concepts apatheia (non-reaction, non-involvement) and adiaphoria (non-differentiation) became central to the Cynic discipline." (Mc Evilley, "The shape of ancient thought", p439)

- ^ "Nagarjuna's work has the whole pattern of the Greek dialectic, with its complex and extensive system of arguments, which in Greece developed over a period of several centuries; yet it arises suddenly, without evidence of developmental stages, in its own tradition" (Mc Evilly, "The shape of ancient thought", p500)

- ^ Mc Evilley, "The shape of ancient thought", p437–444

- ^ a b Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, p. 46

- ^ "Certain Indian notions may have made their way westward into the budding Christianity of the Mediterranean world through the channels of the Greek diaspora." Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, p. 44

- ^ McEvilley, p391