History of Japan

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Japan |

|---|

|

Human habitation in the Japanese archipelago can be traced back to prehistoric times. The Jōmon period, named after its "cord-marked" pottery, was superseded by the Yayoi in the first millennium BC, when new technologies were introduced from continental Asia. During this period, in the first century AD, the first known written reference to Japan was recorded in the Chinese Book of Han. Between the third century and the eighth century, Japan's many kingdoms and tribes gradually unified under a centralized government, nominally controlled by the Emperor. The imperial dynasty established at this time continues to reign over Japan to this day. In 794, a new imperial capital was established at Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto), marking the beginning of the Heian period, which lasted until 1185. The Heian period is considered a golden age of classical Japanese culture. Japanese religious life from this time and onwards was a mix of Buddhism, which had been introduced via Korea, and native religious practices known as Shinto.

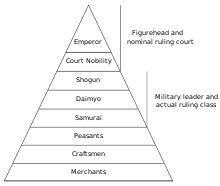

Over the following centuries the power of the emperor and the imperial court gradually declined and passed to the military clans and their armies of samurai warriors. The Minamoto clan under Minamoto no Yoritomo emerged victorious from the Genpei War of 1180–85. After seizing power, Yoritomo set up his capital in Kamakura and took the title of shōgun, which literally means "general". In 1274 and 1281, the Kamakura shogunate withstood two Mongol invasions, but in 1333 it was toppled by a rival claimant to the shogunate, ushering in the Muromachi period. During the Muromachi period regional warlords known as daimyō grew in power at the expense of the shōgun. Eventually, Japan descended into a long period of civil war. Over the course of the late sixteenth century, Japan was reunified thanks to the leadership of the daimyō Oda Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi. After Hideyoshi's death in 1598, Tokugawa Ieyasu came to power and was appointed shōgun by the emperor. The Tokugawa shogunate, which governed from Edo (modern Tokyo), presided over a prosperous and peaceful era known as the Edo period (1600–1868). The Tokugawa shogunate imposed a strict class system upon Japanese society and cut off almost all contact with the outside world.

The American Perry Expedition in 1853–54 ended Japan's seclusion which in turn led to the gradual fall of the shogunate and the return of power to the emperor in 1868. The new national leadership of the following Meiji period transformed their isolated, underdeveloped island country into an empire that closely followed Western models and became a world power. Although democracy developed during the Taishō period (1912–26), Japan's powerful military had great autonomy and overruled Japan's civilian leaders in the 1920s and 1930s. The military invaded Manchuria in 1931, and from 1937 the conflict escalated into a prolonged war with China. Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 led to war with the United States and its allies. Japan's forces soon became overextended, but the military held out in spite of US air attacks which inflicted severe damage on population centers. In August 1945 the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria made it possible for the reigning emperor, Hirohito, to force the military to surrender.

The US occupied Japan until 1952. Under the supervision of the US occupation forces a new constitution was enacted in 1947 that transformed Japan into a parliamentary monarchy. After 1955, Japan enjoyed very high economic growth rates, and became a world economic powerhouse. Since the 1990s, economic stagnation has been a major issue. An earthquake and tsunami in 2011 caused massive economic dislocations and a serious nuclear disaster.

Prehistoric and ancient Japan

Paleolithic and Jōmon period

Modern humans arrived in southern east Asia 60,000 years ago.[1] It is likely that hominids first reached Japan hundreds of thousands of years ago[2] by crossing the land bridges that have periodically formed, linking the archipelago to the continent at Korea in the southwest and Sakhalin in the north. The earliest firm evidence is of early Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers from 40,000 years ago, when Japan was separated from the continent. Edge-ground axes dating to 32-38,000 years ago, found in 224 sites in Honshu and Kyushu, are unlike anything found in neighbouring areas of continental Asia,[3] and have been proposed as evidence for the first Homo sapiens in Japan; watercraft appear to have been in use in this period.[4] The earliest skeletal remains, in Okinawa ('Minatogawa Man') and human skeletons in Ishigaki, date back to 16-20,000 years ago.[5][6]

Pottery described as "cord-marked" was discovered in 1877 in Omori, in one of the first archaeological excavations of shell mounds. The Japanese translation "Jōmon" came to be used to refer to the period when this style of pottery was produced.[7][8]

Environmental changes contributed to a rise in Japan's population during the early Jōmon period from a few thousand to an estimated 260,000 in mid-Jōmon times according to Koyama.[9] The Jōmon people were largely hunter-gatherers, although small-scale slash-and-burn agriculture was practiced as early as 5,700 BC and the cultivation of rice was introduced from Korea as early as 1,000 BC.[10] It has been widely assumed that the Jōmon people led mostly sedentary lives in settlements consisting of a dozen or so pit-houses, though this has been recently[when?] questioned.[11]

Yayoi period (c. 400 BC – 250 AD)

New technologies and modes of living took over from the Jomon culture, spreading from northern Kyushu. The date of the change was until recently thought to be around 400 BC,[12][13] but radio-carbon evidence suggests a date up to 500 years earlier, between 1,000–800 BC.[2][14] The period was named after a district in Tokyo where a new, unembellished style of pottery was discovered in 1884. Though hunting and foraging continued, the Yayoi period brought a new reliance on agriculture.[2] Bronze and iron weapons and tools were imported from China and Korea, and later also produced in Japan.[15] The Yayoi period also saw the introduction of weaving and silk production,[16] glassmaking[17] and new techniques of woodworking.[2]

The population of Japan began to increase rapidly, perhaps with a 10-fold rise over the Jōmon, though calculations have varied from 1.5 to 4.5 million by the end of Yayoi.[18] Skeletal remains from the late Jomon period reveal a deterioration in already poor standards of health and nutrition, in contrast to Yayoi archaeological sites with large structures suggestive of grain storehouses. This change was accompanied by an increase in both the stratification of society and tribal warfare, indicated by segregated gravesites and military fortifications.[2] One particularly large and well-known Yayoi village is the Yoshinogari site which began to be excavated by archeologists in the late-1980s.[19][20]

The Yayoi technologies originated on the Asian mainland. There is debate among scholars as to what extent their spread was accomplished by means of migration or simply a diffusion of ideas, or a combination of both. The migration theory is supported by genetic and linguistic studies.[2][19]Hanihara Kazurō has suggested that the annual immigrant influx from the continent ranged from 350 to 3,000.[21] Genetically, modern Japanese people are most similar to the Yayoi people, whereas Japan's Ainu are, according to the historian Kenneth Henshall, likely to be the direct descendants of the Jōmon. It took time for the Yayoi people and their descendants to fully displace the Jōmon, who continued to exist in northern Honshu until the eighth century AD.[19]

During the Yayoi period the Yayoi tribes gradually coalesced into a number of kingdoms. The earliest written work of history to mention Japan, the Book of Han completed around 82 AD, states that Japan, referred to as Wa, was divided into one hundred kingdoms. A later Chinese work of history, the Wei Zhi, states that by 240 AD one powerful kingdom had gained ascendency over the others. According to the Wei Zhi, this kingdom was called Yamatai and was ruled by Queen Himiko. Modern historians dispute the location of Yamatai and the accuracy of its depiction in the Wei Zhi.[19]

Kofun period (c. 250–538)

During the subsequent Kofun period, most of Japan gradually unified under a single kingdom. The symbol of the growing power of Japan's new leaders was the burial mounds, known as "kofun" in Japanese, which they constructed for themselves from around 250 onwards.[22] Many of the kofun were massive in scale, such as the Daisenryō Kofun, a keyhole-shaped burial mound 486 meters in length which took huge teams of laborers fifteen years to complete.[23] The kofun were often surrounded by and filled with numerous haniwa, clay sculptures often in the shape of warriors and horses.[22]

The center of the unified state was Yamato, located in the Kinai region of modern-day central Japan.[22] The Yamato state extended its power across Japan through a combination of military conquest and cooption of local clans, known in Japanese as "uji", into the ruling aristocracy.[22][23] The rulers of the Japanese Yamato state were a hereditary line of monarchs, later known as "emperors", who still reign over Japan today as the world's longest surviving imperial dynasty.[22] Nevertheless, throughout the large majority of Japanese history the emperors have been essentially figurehead rulers holding little real power.[24]

During this period Japan's new leaders sought and received formal diplomatic recognition from China, and five successive such leaders are known in Chinese accounts as the "Five kings of Wa".[23] Craftsmen and scholars from the Three Kingdoms of Korea also played an important role in transmitting continental technologies, writing systems and administrative skills to Japan during this period.[22][23]

Classical Japan

Asuka period (538–710)

The Asuka period began in 538 with the introduction from the Korean state of Baekje of the new religion of Buddhism, which would henceforth coexist with Japan's native forms of religious practice known as Shinto.[24][25][26] The word "Asuka" refers to a region in Kinai where the de facto imperial capital was located.[25]

In 587, the Buddhist Soga clan took over the government and would control Japan, still nominally ruled by the imperial family, from behind the scenes for nearly sixty years.[27] Prince Shōtoku, a strong advocate of Buddhism and the Soga cause (he was of partial Soga descent), served as regent and de facto leader of Japan between 594 and his death in 622.[28] Shōtoku authored the Seventeen-article constitution, a Confucian-inspired code of conduct for officials and citizens, and also attempting to introduce a merit-based civil service called the "cap and rank system". In a letter he wrote to the Emperor of China in 607, Shōtoku refers to his country as "the land of the rising sun", and by 670 a variant of this expression, "Nihon", would be established as the official name of the Japanese nation which has persisted to this day.[28][24][29]

In 645 AD the Soga clan were overthrown in a coup launched by Prince Naka no Ōe and Fujiwara no Kamatari, the founder of the Fujiwara clan.[30] Their government devised and implemented the far-reaching Taika Reforms which nationalized all land in Japan, to be distributed equally among cultivators, and ordered the compilation of a household registry to form the basis for a new system of taxation.[26][30] Subsequently the Jinshin War of 672, a bloody conflict between two rivals to the throne of Japan, became a major catalyst for further administrative reforms, eventually culminating in the promulgation of the Taihō Code. The Taihō Code consolidated existing statutes and established the structure of the central government and its subordinate local governments.[30][31] These legal reforms created the ritsuryō state, a system of Chinese-style centralized government which remained in place for half a millennium.[31]

Nara period (710-794)

In the year 710 the Japanese government moved to a grandiose new capital constructed at Heijō-kyō (present-day Nara). The new capital city was constructed in a grid pattern modeled off Chang'an, the capital of the Chinese Tang dynasty.[32]

The Nara period is noted for its major literary accomplishments. The first two books produced in Japan, the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, were completed in the years 712 and 720, respectively. These chronicles give a legendary account of Japan's beginnings and recount the history of the ruling imperial family which, the accounts claim, was directly descended from the gods. Soon after the earliest extant Japanese collections of Chinese and Japanese poetry also appeared: respectively, the Kaifūsō in 751 and the Man'yōshū in the latter half of the eighth or the beginning ninth century.[33]

A series of natural disasters occurred during the Nara period including wildfire, droughts, famines, and outbreaks of disease, including a smallpox epidemic that killed more a quarter of Japan's population. Emperor Shōmu, who reigned from 724 to 749, feared that his own lack of piousness was the cause of the trouble, and so increased the government's promotion of Buddhism, including the construction of Tōdai-ji Temple.[34] Nevertheless, Japan had entered a phase of population decline which would continue well into the subsequent Heian period.[35]

Heian period (794–1185)

The capital of Japan, after being briefly situated in Nagaoka-kyō from 784, was moved in 794 to Heian-kyō, present-day Kyoto, where it would remain until 1868.[36] At Heian-kyō the imperial court of the Emperor of Japan was a vibrant center of high art and culture.[37] Its literary accomplishments were especially noteworthy, including the poetry collection Kokinshū, the Tosa Diary, and the novel The Tale of Genji.[37][38] The Tale of Genji, written by Murasaki Shikibu in the early eleventh century likely between 1001 and 1113, is considered to be the supreme masterpiece of Japanese literature.[39] The appearance of the kana syllabaries was part of a general trend of declining Chinese influence during the Heian period. The Japanese missions to Tang China ended during the ninth century and afterwards Japan gradually developed more typically Japanese forms of art and poetry.[37] A major architectural achievement of the period, apart from the construction of the Heian-kyō itself, was the temple of Byōdō-in built in 1053 in Uji.[40]

Political power within the imperial court itself soon passed from the Emperor to the Fujiwara clan, a family of court nobles who had been close to the imperial family for centuries. It was in 858 that Fujiwara no Yoshifusa had himself declared regent, sesshō in Japanese, to the underage emperor. His son Fujiwara no Mototsune created the office of kampaku which could rule in the place of an adult reigning emperor.[37][41] Through the offices of sesshō and kampaku, the Fujiwara clan held onto power until the late eleventh century when the practice of "cloistered rule" became prevalent. Cloistered rule meant that the reigning emperor would retire early in order to manipulate the nominally ruling emperor from behind the scenes.[41]

However, throughout the Heian period the power of the imperial court was in continuous decline. The court became so self-absorbed with power struggles in Kyoto and with the artistic pursuits of court nobles that it increasingly neglected the administration of government outside the capital. The nationalization of land which had been undertaken as part of the ritsuryō state decayed as various noble families and religious orders succeeded at securing tax exempt status for their private manors, called shōen in Japanese.[37] By the eleventh century more land in Japan was controlled by shōen owners than was controlled by the central government. The imperial court was thus deprived of the tax revenue it had been using to pay for its national army. In response, the owners of the shōen set up their own armies composed of warriors who were known as the samurai.[42] Two powerful noble families, the Taira clan and the Minamoto clan, both of whom were descended from branches of the Japanese imperial family, acquired large armies and many shōen outside the capital. The central government began to employ these two warrior clans to help it suppress rebellions and piracy.[41]

In 1156, when a dispute over the succession to the imperial throne erupted in Kyoto, the two rival claimants hired the Taira and Minamoto clans respectively in the hopes of securing the throne by military force. In this war, the Hōgen Rebellion, the Taira clan led by Taira no Kiyomori defeated the Minamoto clan. Kiyomori used his victory to accumulate power for himself in Kyoto until 1180 when he was challenged by an uprising led by Minamoto no Yoritomo, a member of the Minamoto clan whom Kiyomori had exiled to Kamakura. Though Taira no Kiyomori died in 1181, the bloody Genpei War between the Taira and Minamoto families continued until 1185 when the Minamoto scored a decisive victory at the naval battle of Dan-no-ura. Yoritomo and his retainers thus became the de facto rulers of Japan.[37]

Medieval Japan

Kamakura period (1185–1333)

Upon seizing power, Yoritomo chose to rule in consort with the imperial court in Kyoto. Though Yoritomo set up his own government in Kamakura, which is in the Kantō region east of Kyoto, he styled it as a bakufu, which means "tent headquarters", implying that the Kamakura government was merely the army of the central imperial court. In 1192 the emperor declared Yoritomo shōgun, an abbreviation of the title "seii tai-shōgun" which means "barbarian-subduing great general".[43] Japan would largely remain under military rule from that date until 1868. However, the office of shōgun weakened in the immediate aftermath of Yoritomo's death in 1199. Behind the scenes, Yoritomo's wife Hōjō Masako, who was also a member of a samurai clan, became the true power behind the government. In 1203 her father Hōjō Tokimasa was appointed regent to the shōgun, Yoritomo's son Minamoto no Sanetomo, and henceforth the Minamoto shōguns became puppets of the Hōjō regents who wielded actual power.[44]

The regime which Yoritomo had established and which was kept in place by his successors was decentralized and feudalistic in structure in contrast with the earlier ritsuryō state.[43] Yoritomo selected the provincial governors, known under the titles of shugo or jitō, from among his close vassals, the gokenin. The Kamakura shogunate allowed its vassals to maintain their own armies and to administer law and order in their provinces on their own terms.[45]

The samurai armies of the whole nation were mobilized in 1274 and 1281 to confront two full-scale invasions launched by Kublai Khan of the Mongol Empire.[46] Though outnumbered by an enemy equipped with superior weaponry, the Japanese fought the Mongols to a standstill in Kyushu on both occasions until the Mongol fleet was destroyed by typhoons which the Japanese called kamikaze, meaning "divine wind". In spite of the Kamakura shogunate's victory, its finances were so badly depleted by the cost of defending Japan that it was unable to provide compensation to its vassals for their role in the victory. This would have permanent deleterious consequences for the shogunate's relations with the samurai class.[43]

In spite of this, Japan entered a period of considerable prosperity and population growth starting around 1250. The origins of this growth lay in rural areas where greater use of iron tools and fertilizer, improved irrigation techniques, and double-cropping caused an increase in agricultural productivity and increase in the size of rural villages. There were also fewer famines and epidemics which caused cities to grow and commerce to boom.[47] Another major trend of the Kamakura period was the rise of popular Buddhism. Buddhism, which had previously been largely a religion of the elites, was brought to the masses by such prominent monks as Hōnen, who established Pure Land Buddhism in Japan, and Nichiren, who founded Nichiren Buddhism. Another form of Buddhism, Zen, spread widely among the samurai class.[43][48]

Ultimately, discontent among the samurai proved decisive in ending the Kamakura shogunate. In 1333 Emperor Go-Daigo launched a rebellion in the hopes of restoring full power to the imperial court. The shogunate sent one of its generals, Ashikaga Takauji to quell his revolt, but Takauji and his men instead joined forces with Go-Daigo and overthrew the Kamakura shogunate.[43]

Muromachi period (1333–1568)

Ashikaga Takauji and many other samurai soon became dissatisfied with Emperor Go-Daigo's Kemmu restoration, an ambitious attempt to monopolize power within the imperial court. After Go-Daigo refused to appoint Takauji shōgun, Takauji rebelled. In 1338 Takauji captured Kyoto and installed a rival member of the imperial family, Emperor Kōmyō, on the throne who did appoint him shōgun. Emperor Go-Daigo responded by fleeing to the southern city of Yoshino where he set up a rival government. This ushered in a prolonged period of warfare between the "Northern Court" and the "Southern Court".[49]

Meanwhile, Takauji set up his shogunate in the Muromachi district of Kyoto. However, the shogunate was faced with the twin challenges not only of fighting the Southern Court, but also of maintaining its authority over its own subordinate governors. Like the Kamakura shogunate, the Muromachi shogunate appointed its allies to rule in the provinces, but increasingly these men styled themselves as the daimyo of their respective domains and they often refused to obey the wishes of the shōgun. One of the Ashikaga shōguns who was most successful at bringing the country together was Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, Takauji's grandson, who came to power in 1368 and remained influential until his death in 1408. Yoshimitsu expanded the power of the shogunate and in 1392 he brokered a deal to bring the Northern and Southern Courts together and end the civil war. Henceforth the emperor and his court were kept under the tight control of the shogunate.[49][50][51]

In spite of the war, Japan's relative economic prosperity which began in the Kamakura period continued well into the Muromachi period. By 1450 Japan's population stood at ten million, compared to six million at the end of the thirteenth century. Commerce flourished as never before, including considerable trade with China and Korea.[47] It was also during the Muromachi period that Japan's cultural elite developed some of Japan's most representative art forms, including ink wash painting, flower arrangement, the tea ceremony, Japanese gardening, bonsai, and noh theater.[50]

Ultimately, during the final century of the Ashikaga shogunate, the country would descend into another, even more violent period of civil war which started in 1467 when the Ōnin War broke out over who would succeed the ruling shōgun. The daimyo each took sides and burned Kyoto to the ground while battling for their preferred candidate. Though the succession was finally worked out in 1477, by then the shōgun had lost all power over the daimyo who now ruled hundreds of de facto independent states spread across Japan.[51] The daimyo immediately began fighting amongst themselves for control of the country during the so-called "Warring States period". Not only the daimyo but also rebellious peasants and "warrior monks" affiliated with Buddhist temples raised their own armies.[50]

It was amidst this on-going anarchy that, in 1543, a Chinese ship was blown off course and landed on the Japanese island of Tanegashima just south of Kyushu. The three Portuguese traders on board were the first Europeans to set foot in Japan. Over the coming decades European traders would introduce many new trade items to Japan, most importantly the musket.[49] By 1556 Japan's daimyos were already using about 300,000 muskets in their armies.[52] The Europeans also brought Christianity, which soon came to have a substantial following in Japan. The Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier disembarked in Kyushu in 1549.[49]

Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568–1600)

During the second half of the seventeenth century Japan would gradually reunify thanks to the efforts of two powerful warlords, the daimyo Oda Nobunaga and the peasant-turned-general Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The period takes its name from Nobunaga's headquarters, Azuchi Castle, and Hideyoshi's headquarters, Momoyama Castle.[53]

Nobunaga was the daimyo of the small province of Owari who burst onto the scene suddenly in 1560 when, during the Battle of Okehazama, his army defeated a force several times its own size led by the powerful daimyo Imagawa Yoshimoto. Nobunaga, who was renowned for both his brilliant strategic leadership and his extreme ruthlessness, used the new European imports of Christianity and muskets to his advantage. He encouraged Christianity in order to whip up hatred of his Buddhist enemies and to forge strong relationships with European arms merchants. He then equipped his armies with muskets and trained them using new and innovative tactics. He also promoted talented men regardless of their social status, including his peasant servant Toyotomi Hideyoshi who became one of his best generals.[54][55][56]

The Azuchi-Momoyama period is often said to have begun in 1568 when Nobunaga seized Kyoto and thus effectively brought an end to the Ashikaga shogunate. Oda Nobunaga had come close to reuniting all Japan by military force when, in 1582, he was killed during an abrupt attack on his encampment by one of his own rebellious officers, Akechi Mitsuhide. Hideyoshi avenged Nobunaga by crushing Akechi's uprising, and then emerged as Nobunaga's successor. Hideyoshi completed the reunification of Japan by conquering Shikoku, Kyushu, and the lands of the Hōjō family in eastern Japan. He launched sweeping changes to Japanese society, including the confiscation of swords from the peasantry, new restrictions on daimyo, persecutions of Christians, a thorough population census, and a new law effectively forbidding the peasants and samurai from changing their social class. As Hideyoshi's power expanded, he dreamed of conquering China, and as a stepping stone towards this goal he launched two massive invasions of Korea starting in 1592. Hideyoshi failed to defeat the Chinese and Korean armies arrayed against him on the Korean peninsula and the war only ended with his death in 1598.[54][55][57]

In the hopes of founding a new dynasty, Hideyoshi had asked his most trusted subordinates to pledge loyalty to his infant son Toyotomi Hideyori. Despite this, almost immediately after Hideyoshi's death war broke out between Hideyori's allies and those loyal to Tokugawa Ieyasu, a daimyo and former ally of Hideyoshi.[54] Tokugawa Ieyasu won a decisive victory over his opponents at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, ushering in 268 uninterrupted years of rule by the Tokugawa family.[58]

Modern Japan

Edo period (1600–1868)

The Edo period was a long era characterized by relative peace, stability, and prosperity under the tight control of the Tokugawa shogunate, which ruled from the eastern city of Edo, now called Tokyo.[59][60] In 1603 Emperor Go-Yōzei declared Tokugawa Ieyasu shōgun, though Ieyasu would abdicate just two years later in a successful bid to groom his son as the second shōgun of what would become a long dynasty.[59] Still, it took time for the Tokugawas to consolidate their rule. A plan to make their rival Hideyori a daimyo failed and instead Hideyori's castle was stormed and destroyed during the Siege of Osaka in 1615.[61] Soon after this the shogunate promulgated the Laws for the Military Houses imposing tighter controls on the daimyo. This was later coupled with the "alternate attendance system" which required each daimyo to spend every other year in Edo under the watchful eye of the shōgun.[59][62] Even so, the daimyo continued to maintain a significant degree of autonomy in their domains within a system that the historian Edwin Reischauer called "centralized feudalism".[60] The central government of the shogunate in Edo, which quickly became the largest city in the world by population, took counsel from a group of senior advisors known as rōjū and employed samurai as bureaucrats.[59][63] Meanwhile, the Emperor in Kyoto was funded lavishly by the government but allowed no political power.[64]

The Tokugawa shogunate went to great lengths to suppress social unrest. Harsh penalties, including crucifixion, beheading, and death by boiling, were decreed for even the most minor offenses. Christianity, which was seen as a potential threat, was gradually clamped down on until finally, after the Christian-led Shimabara Rebellion of 1638, the religion was completely outlawed. To prevent further such foreign ideas from sowing dissent in the minds of the Japanese, the Tokugawa shogunate adopted a foreign policy of isolationism known as "sakoku", which means "closed country". Under this policy, no Japanese people were allowed to travel abroad, to return from overseas, or to build ocean-going vessels. The only Europeans allowed on Japanese soil were the Dutch, who were granted just one trading post on the island of Dejima. Apart from the Netherlands, China and Korea were the only other countries permitted to trade with Japan, but many foreign books were banned from import.[59][60]

One of the most significant social policies of the Tokugawa shogunate was the freezing of Japan's social classes. The Tokugawas had adopted the philosophy of Neo-Confucianism as their state ideology, and were thus inspired to divide society into the Neo-Confucian hierarchy of four occupations, samurai, peasant farmers, artisans, and merchants. By law, no person was permitted to adopt a different occupation from the one he was born into or to marry a person of a different occupation. Outside of these four classes there were also court nobles, clergymen, and the untouchable burakumin class.[59][65]

During the first century of Tokugawa rule between 1600 and 1700 Japan's population doubled to thirty million people, due in large part to agricultural growth, but after that the population would remain stable for the rest of the period. The shogunate's construction of new roads, elimination of road and bridge tolls, and standardization of coinage promoted commercial expansion which also benefited the merchants and artisans of the cities.[66] Urbanization did take place, but almost ninety percent of the population continued to live in rural areas.[67] However, both the inhabitants of cities and of rural communities would benefit from one of the most notable social changes of the Edo period, increased literacy. The number of private schools in Japan, particularly schools attached to temples and shrines, greatly expanded, raising Japan literacy rate to thirty per cent. This rate may have been the world's highest at that time.[59]

The Edo period was also a time of prolific cultural output. It was during this period that haiku emerged as a major Japanese art form. Matsuo Bashō, generally considered Japan's greatest haiku poet, was active during the first century of Tokugawa rule. Two important new styles of theater, kabuki drama and the puppet theater known as bunraku, were also created and popularized. Poetry and theater were both widely patronized by the wealthy merchant class, who were said to have lived hedonistic lives in a "floating world", or ukiyo in Japanese. The ukiyo lifestyle inspired both popular novels known as "books of the floating world" and art known as "pictures of the floating world", the latter of which were often woodblock prints. Many of Japan's greatest woodblock artists lived during the Tokugawa period, including Katsushika Hokusai.[68]

Decline and fall of the shogunate

By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century the shogunate was showing signs of weakening. The dramatic growth of agriculture which had characterized the early Edo period was over, resulting in two devastating famines, the Tenmei famine and the Tenpo famine, both of which were poorly handled by the government. Peasant unrest increased considerably and government revenues fell.[69][70] The shogunate responded by cutting the pay of the already financially distressed samurai, many of whom were working part-time jobs to make a living.[71] Discontented samurai would soon play a major role in engineering the downfall of the Tokugawa shogunate.[72][73]

At the same time, the people of Japan were being inspired by new ideas and fields of study. Dutch books which were brought into Japan stimulated interest in Western learning, which was called rangaku or "Dutch learning", though the study of Western science and civilization was tightly controlled and sometimes banned by the shogunate.[70][73] Another new philosophy was kokugaku or "National Learning", which claimed to promote native Japanese values. Kokugaku criticized the Chinese-style Neo-Confucianism advocated by the shogunate and instead emphasized the divine authority of the Japanese emperor which was said, according to the Shinto faith, to have had its roots in Japan's "Age of the Gods".[74]

In 1853, while these trends were on-going, Japan was abruptly thrown into turmoil by the arrival of a fleet of American ships commanded by Commodore Matthew C. Perry. Perry was on a mission from the US government to forcibly end Japan's isolationist policies. He demanded that American ships be permitted to acquire provisions and trade at Japanese ports, and the shogunate, which had no defense against Perry's gunboats, soon had little choice but to agree. After this the United States and other Western powers, including Great Britain and Russia, imposed what became known as "unequal treaties" on Japan which stipulated that Japan must allow their citizens to visit or reside on Japanese territory but must not levy tariffs on their imports or try their citizens in Japanese courts.[70][75]

The shogunate's failure to stand up to the Western powers angered many Japanese, particularly those of the southern domains of Chōshū and Satsuma. Here many samurai, who were inspired by the nationalist doctrines of the kokugaku school, adopted the slogan of sonnō jōi, which means "revere the Emperor, expel the barbarian". The two domains eventually formed an alliance, and then in 1868 convinced the young Emperor Meiji and his advisors to issue an imperial rescript calling for an end to the Tokugawa shogunate. The combined armies of Chōshū and Satsuma marched on Edo, an event known as the Boshin War. They overthrew the shogunate and ushered in the Meiji period.[70][76]

Meiji period (1868–1912)

Starting in 1868 Japan underwent major political, economic, and cultural changes, many of which were spearheaded by Japan's new leadership who desired Japan to become a modern, unified nation-state which could stand as an equal to the imperialist powers of the West. Nominally the emperor was restored to supreme power, but in actuality the most powerful men in the government were former samurai from the domains of Chōshū and Satsuma, not Emperor Meiji, who was only fifteen years old in 1868. In 1869 the imperial family moved to Edo, which was renamed Tokyo, meaning "eastern capital".[77]

Political and social reforms

The Meiji government radically changed the feudal structures of the Edo period by abolishing the domains of the daimyo and replacing them with prefectures, instituting comprehensive tax reform, abolishing the Neo-Confucian class structure, and lifting the ban on Christianity. Other major priorities of the new government included the construction of Japan's first railways and telegraph lines, as well as its first universal education system. In 1872 the government announced its intention to make primary school attendance compulsory, and by 1906 the attendance rate was 90%.[77][78]

The Meiji government strongly promoted Western science and medicine, as well as Westernization in general. The government hired hundreds of advisors from Western nations with expertise in such diverse fields as education, mining, banking, law, military affairs, and transportation to remodel Japan's institutions along Western lines. Japanese people also began using the Gregorian calendar, wearing Western clothing, and cutting their hair in Western style. One leading advocate of Westernization was the popular writer Fukuzawa Yukichi.[77][79] However, at the same time that the government was adopting Western culture, it was also seeking to develop a unique form of Japanese nationalism. Under this system the Emperor was declared a living god and the native Japanese religion of Shinto was elevated into the patriotic institution known as State Shinto. Patriotic values and loyalty to the Emperor were instilled in schools nationwide.[77][80]

Government institutions also developed rapidly in response to the rise of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement, a grassroots campaign demanding greater popular participation in politics. Itō Hirobumi, the first prime minister of Japan, responded by writing the Meiji Constitution, which was formally promulgated in 1889. The new constitution established an elected lower house, the House of Representatives, in accordance with popular demand for such an institution, but its powers were restricted in many ways. Only two percent of the population were eligible to vote in elections to the House, and the House's legislation required the support of the unelected upper house, the House of Peers, to pass legislation. Furthermore, the Emperor was nominally an absolute monarch, and both the cabinet of Japan and the Japanese military were directly responsible, not to the elected legislature, but to the Emperor.[77]

Rise of imperialism and the military

Yamagata Aritomo, who was born a samurai in Chōshū domain, was the mastermind behind the reform and enlargement of the new Imperial Japanese Army. Within the Meiji government he successfully pressed for military modernization and the introduction of national conscription.[81][82] Japan's new army was put to use in 1877 to crush the Satsuma Rebellion, a revolt of discontented samurai in southern Japan.[77]

The Japanese military also spearheaded Japan's expansion abroad. The Meiji government was of the view that Japan would have to acquire its own colonies abroad in order to compete with the Western colonial powers. After consolidating its control over Hokkaido and the Ryukyu Islands, it next turned its attention to China and Korea.[83] In 1894 Japanese and Chinese troops clashed with one another in Korea, where they were both stationed in order to suppress Korea's Donghak Rebellion. During the ensuing First Sino-Japanese War, Japan's highly motivated and well led armed forces successfully defeated the more numerous and better equipped military of Qing China. As the spoils of victory, Japan was ceded the island of Taiwan in 1895, and Japan's government also gained enough international prestige to complete its long-term goal of renegotiating the "unequal treaties". In 1902 Japan signed an important military alliance with Great Britain.[84]

The next nation Japan clashed with was Russia, which was expanding its power in Asia. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904 to 1905 ended with the dramatic naval Battle of Tsushima which sealed another victory for Japan's military. As a result of the war, Japan was able to claim Korea as a protectorate in 1905, followed by the full annexation of Korea in 1910.[77]

Economic modernization and labor unrest

During the Meiji period Japan underwent a dramatic transition from an agricultural economy to an industrial economy. Both the Japanese government and private entrepreneurs imported Western technology and know-how in order to create factories capable of producing a wide range of manufactured goods. By the end of the Meiji period the majority of Japan's exports were manufactured goods.[77] The owners of some of Japan's most successful new businesses and industries constituted huge, family-owned conglomerates known as zaibatsu. Mitsubishi and Sumitomo were two prominent zaibatsu which grew rapidly during this period.[85] The phenomenal growth of urban industry sparked equally rapid urbanization. The percentage of the population working in agriculture shrank from 75 percent in 1872 to 50 percent within a decade of the end of the Meiji period.[86]

Japan enjoyed solid economic growth at this time and most people lived longer and healthier lives. The population rose from 34 million in 1872 to 52 million in 1915.[87] Nonetheless, working conditions in factories were often extremely poor. Labor unrest became gradually more acute over the course of the Meiji period and many workers and intellectuals embraced socialist ideas. The Meiji government responded by harshly suppressing dissent. After the High Treason Incident of 1910, a plot by radical socialists to assassinate the Emperor, a secret police force called the Tokkō was established to root out left-wing agitators.[88][89] On the other hand, the government also introduced some social legislation such as the Factory Act of 1911 which introduced maximum work hours and a minimum age for employment.[89]

Taishō period (1912–1926)

Following the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912, Emperor Taishō acceded to the throne. During his short reign Japan developed stronger democratic institutions and grew in international power.

The period opened with the Taisho Political Crisis in which mass protests and riots organized by Japanese political parties succeeded in forcing General Katsura Tarō to resign as prime minister. This event increased the power of Japan's political parties over the ruling oligarchy, as did the similar Rice Riots of 1918.[88][90] By the end of the Taishō period, which came to be known as the era of "Taishō demoracy", Japanese politics was dominated by the Seiyūkai and Minseitō parties. In 1925 universal male suffrage was introduced for elections to the House of Representatives. On the other hand, this was also the same year as the passage of the Peace Preservation Law, a far-reaching law prescribing harsh penalties for "subversive" communist and socialist activity.[91]

Meanwhile, Japan's participation in World War I on the side of the Allies sparked an unprecedented spurt of economic growth within Japan and also earned Japan new colonies in the South Pacific which were seized from Germany.[92] After the war Japan signed the Treaty of Versailles and enjoyed generally good relations with the international community through its membership in the League of Nations and participation in various international disarmament conferences. However, in 1923 the capital city of Tokyo was decimated by a powerful earthquake which left roughly 100,000 people dead.[90]

Shōwa period (1926–1989)

In 1926 Emperor Taishō died and Emperor Hirohito ascended to the throne. The name of Hirohito's sixty-three year reign, the longest in Japanese history, was "Shōwa", which means "illustrious peace".[93][94] However, the first twenty years of Hirohito's reign were characterized by the rise of extreme nationalism and by a series of expansionist wars. After suffering defeat in World War II, Japan was occupied by foreign powers for the first time in its history, and then re-emerged as a major world economic power.[94]

The road to war

Though left-wing groups had been subject to violent suppression by the end of the Taishō period, radical right-wing groups, inspired by fascism and Japanese nationalism, rapidly grew in popularity.[95] The extreme right became influential throughout Japanese government and society, notably within the Kwantung Army, a Japanese army stationed in China along the Japanese-owned South Manchuria Railroad.[96] During the Manchurian Incident of 1931, radical army officers bombed a small portion of the South Manchuria Railroad and, falsely attributing the attack to the Chinese, invaded Manchuria. The Kwantung Army conquered Manchuria and set up the puppet government of Manchukuo there on its own authority without any permission from the Japanese government. International criticism of Japan following the invasion led Japan to withdraw from the League of Nations.[94]

Japanese Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai of the Seiyūkai Party, who attempted to restrain the Kwantung Army, was assassinated in 1932 by right-wing extremists. Because of growing opposition within the Japanese military and the extreme right to party politicians, who they saw as corrupt and self-serving, Inukai was the last party politician to govern Japan in the pre-World War II era.[97][98] In February of 1936 young radical officers of the Japanese Army attempted a coup d'état. They succeeded in assassinating many moderate politicians but the coup was ultimately suppressed.[94] In the wake of the coup the Japanese military consolidated its control over the political system and most political parties were abolished when the Imperial Rule Assistance Association was founded in 1940.[99]

Meanwhile, Japan's expansionist vision grew increasingly bold. Many of Japan's political elite aspired to have Japan acquire new territory for resource extraction and settlement of surplus population. These ambitions led to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. The Japanese military failed to defeat the Chinese government led by Chiang Kai-shek and the war descended into a bloody stalemate which lasted until 1945. Japan's stated war aim was to establish the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a vast pan-Asian union under Japanese domination.[94] Emperor Hirohito's role in Japan's foreign wars remains a subject of controversy, with various historians portraying him as either a powerless figurehead or an enabler and supporter of Japanese militarism.[100]

The United States strongly opposed Japan's invasion of China and responded by imposing a series of increasingly stringent economic sanctions on Japan. These sanctions sought to deprive Japan of the resources it needed to continue its war in China. Japan responded by forging an alliance with Germany and Italy in 1940, known as the Tripartite Pact, though this only worsened its relations with the USA.[94][101]

World War II

In late-1941 Japan's government, led by Prime Minister and General Hideki Tojo, decided to break the US-led economic embargo through force of arms. On December 7, 1941 the Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Through this act, Japan brought America into World War II on the side of the Allies. Japan followed up by successfully invading the Asian colonies of the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands, including the Philippines, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Singapore, Burma, and the Dutch East Indies.[94]

In the early stages of the war, Japan scored victory after victory. The tide began to turn against Japan following the Battle of Midway in June 1942, in which four Japanese aircraft carriers were sunk, and the subsequent Battle of Guadalcanal, in which US troops wrestled the Solomon Islands from Japanese control. During this period the Japanese military was responsible for numerous war crimes, including mistreatment of POWs, massacres of civilians, and use of chemical and biological weapons.[94] The Japanese military also earned a reputation for fanaticism, often employing suicide tactics and fighting almost to the last man against overwhelming odds.[102] In 1944 the Japanese Navy began deploying squadrons of "kamikaze", pilots who would attempt to destroy enemy ships by crashing their own planes into them.[94]

On the home front, life in Japan became increasingly difficult for civilians due to stringent rationing of food, electrical outages, and a brutal government crackdown on any form of dissent. In 1944 the US Army captured the island of Saipan, which allowed the United States to begin widespread bombing raids on the Japanese mainland. Over half of the total area of Japan's major cities was completely destroyed through bombing.[103][104]

On August 6, 1945 Japan was subject to the first nuclear attack in history when an atomic bomb was dropped over the city of Hiroshima, instantly killing 90,000 people. On August 9, 1945 a second atomic bomb was dropped over Nagasaki. That was the same day that the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchukuo. Over the coming days Emperor Hirohito played a key role in convincing the leaders of Japan's military that the situation was hopeless. On August 15, 1945 Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. During the war Japan had suffered almost three million military casualties and over half a million civilian casualties.[94]

Occupation of Japan

Between 1945 and 1952 Japan experienced dramatic political and social transformation under a US-led occupation regime. American General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of Allied Powers, served as Japan's de facto leader. Macarthur played a central role in implementing the occupations reforms, many of which were inspired by America's New Deal.[105][106]

The occupation sought to decentralize power in Japan by breaking up the zaibatsu, promoting labor unionism, and transferring ownership of agricultural land from the landlords to their tenant farmers. Other major goals of the occupation were the demilitarization and democratization of Japan's government and society. Japan's army and navy were disarmed, all its colonies were granted independence, the Peace Preservation Law and Tokkō were abolished, and war criminals were tried by the International Military Tribunal of the Far East. The cabinet of Japan would henceforth be directly responsible, not to the Emperor, but to the elected National Diet. The Emperor was permitted to remain in power, although he was ordered to renounce his divinity, which had been a pillar of the prewar State Shinto system. Japan's new constitution, which came into effect in 1947, guaranteed civil liberties, labor rights, and women's suffrage. It also included the famous Article 9, through which Japan renounced its right to ever go to war with another nation.[105][107]

In 1951 Japan signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty which officially normalized relations between Japan and the United States. The occupation of Japan ended in 1952, though the United States has continued to operate military bases on Japanese territory.[105]

Postwar growth and prosperity

Shigeru Yoshida, who served as prime minister from 1946 to 1947 and again from 1948 to 1954, played a key role in guiding Japan through the occupation. He formulated the influential Yoshida Doctrine, which argued that Japan should forge a tight relationship with the United States and focus on developing the economy at home rather than pursuing a pro-active foreign policy abroad. Ultimately, Yoshida's party, the Liberal Party, would merge in 1955 into the new Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), a right-wing, pro-business party which would win every election for the remainder of the Shōwa period.[108][109]

Though the Japanese economy had been devastated by World War II, an austerity program known as the Dodge Line, which was implemented in 1949, ended inflation. The subsequent Korean War was also a major boon to Japanese business.[105] In 1949 the Yoshida cabinet created the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, or MITI, with a mission to promote economic growth through close cooperation between the government and big business. MITI sought successfully to promote manufacturing and heavy industry, as well as encourage exports.[108][110] However, Japan's postwar economic growth rested on a large number of factors including technology and quality control techniques imported from the West, close economic and defense cooperation with the United States, non-tariff barriers to imports, restrictions on labor unionization, the long work hours of Japanese citizens, and a generally favorable global economic environment.[108]

According to the historian Conrad Totman, "For the Japanese people as a whole, the three decades after 1960 were arguably the best in their entire history". By 1955 the Japanese economy had grown beyond prewar levels.[93] After that, Japan's gross national product expanded at a rate of over 10% annually and real wages more than tripled.[108] Japan's population increased dramatically to 123 million by 1990, life expectancy rose, and the Japanese people became wealthy enough to purchase a wide array of consumer goods, including televisions, radios, and cars.[93][111] Japan itself became the world's largest producer of all three of these products. By the end of the Shōwa period, Japan was the world's second largest economy and was renowned as a technological leader.[108]

During the Cold War, Japan was a close ally of the United States, though this alliance was not unanimously supported by the Japanese people. Hundreds of thousands of Japanese protested in 1960 against amendments to the US-Japan Security Treaty.[93] Japan successfully normalized relations with the Soviet Union in 1956, in spite of an ongoing dispute over the ownership of the Kuril Islands, and with South Korea in 1965, in spite of an ongoing dispute over the ownership of the islands of Liancourt Rocks.[112] In accordance with US policy, Japan recognized the Republic of China on Taiwan as the legitimate government of China after World War II, though Japan eventually switched its recognition to the People's Republic of China in 1972.[113]

Heisei period (1989–present)

Emperor Hirohito died in January 1989, and his eldest son Akihito assumed the throne. Akihito's reign name, "Heisei", means "achieving full peace".[114]

At the beginning of the Heisei period, Japan's economic miracle came to a spectacular end. The Japanese economy became overheated in the late-1980s. When the economic bubble finally popped in 1989, stock prices and land prices plunged as Japan entered a deflationary spiral. Japan's banks found themselves quickly saddled with insurmountable debts which hindered Japan's economic recovery. Economic stagnation was further worsened by a continuing decline in Japan's birth rate, which had fallen far below replacement level. The 1990s are often referred to as Japan's Lost Decade, though economic performance was frequently poor in the following decades as well and the stock market never again reached its pre-1989 highs.[114][115]

In the early-1990s Japan's faltering economy weakened the LDP's dominant position in Japanese politics, as did several corruption scandals affecting high-ranking LDP politicians. Ultimately however, Japan was governed by non-LDP prime ministers for only two periods, between 1993 and 1996 and between 2009 and 2012.[114][116] Historian Conrad Totman attributes the LDP's staying power to its cautious economic policy and its cultivation of close ties with business groups. Furthermore, while unemployment rates rose during Japan's economic troubles, they still remained lower than the average for first world nations. For those who were working, average household income decreased only slightly.[117]

On March 11, 2011, Japan's Tōhoku region was struck by a massive earthquake and tsunami which left up to 20,000 people dead and caused 300 billion US dollars in damage. The damage extended to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which experienced a nuclear meltdown and severe radiation leakage. One historian described this as "Japan's greatest disaster since the Pacific War."[114]

See also

- Timeline of Japanese history

- History of Asia

- History of Tokyo

- List of Emperors of Japan

- List of Prime Ministers of Japan

- Politics of Japan

- Historiography of Japan

Academic journals

- Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History, in Japanese

- Japanese Journal of Religious Studies

- Journal of Japanese Studies

- Monumenta Nipponica, Japanese studies, in English

- Social Science Japan Journal

References

- ^ Roscoe Stanyon, Marco Sazzini, Donata Luiselli (6 February 2009). "Timing the first human migration into eastern Asia". PubMed Central. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Conrad Schirokauer; Miranda Brown; David Lurie (1 January 2012). A Brief History of Chinese and Japanese Civilizations. Cengage Learning. p. 138–143. ISBN 0-495-91322-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sanz, Nuria (27 October 2014). Human origin sites and the World Heritage Convention in Asia. UNESCO. pp. 157–159. ISBN 978-92-3-100043-0.

- ^ Tsutsumi Takashi (18 January 2012). "MIS3 edge-ground axes and the arrival of the first Homo sapiens in the Japanese archipelago". Quaternary International Vol. 248, 70-78. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ "Ancient burial remains in Okinawa cave may fill void in Japanese ancestry". The Asahi Shimbun. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Ryohei NAKAGAWA1, Naomi DOI, Yuichiro NISHIOKA, Shin NUNAMI, Heizaburo YAMAUCHI, Masaki FUJITA, Shinji YAMAZAKI, Masaaki YAMAMOTO, Chiaki KATAGIRI, Hitoshi MUKAI, Hiroyuki MATSUZAKI, Takashi GAKUHARI, Mai TAKIGAMI, Minoru YONEDA (2010). "Pleistocene human remains from Shiraho-Saonetabaru Cave on Ishigaki Island, Okinawa, Japan, and their radiocarbon dating". ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 118(3), 173–183. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ John Whitney Hall (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-521-22352-2.

- ^ Keiji Imamura. "Collections of Morse from The Shell Mounds of Omori". Digital Museum, University of Tokyo. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 22 (help) - ^ Junko Habu,Ancient Jomon of Japan, Cambridge University Press 2004 pp.46–49.

- ^ Henshall, 8–10.

- ^ Junko Habu,Ancient Jomon of Japan, pp.85ff.

- ^ Bruce Loyd Batten,To the Ends of Japan: Premodern Frontiers, Boundaries, and Interactions, University of Hawaii Press, 2003 p. 60.

- ^ Ann Kumar, Globalizing the Prehistory of Japan: Language, Genes and Civilisation, Routledge, 2008 p.1

- ^ Neil Asher Silberman (ed.)The Oxford Companion to Archaeology,OUP USA, 2012 p. 155.

- ^ Keiji Imamura (January 1996). Prehistoric Japan: New Perspectives on Insular East Asia. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 168–170. ISBN 978-0-8248-1852-4.

- ^ Simon Kaner, 'The Archaeology of Religion and Ritual in the Japanese Archipelago,' in Timothy Insol (ed.),The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion, OUP Oxford, 2011 pp.457-468 p.462.

- ^ YOSHIO TSUCHIYA (1998). "A BRIEF HISTORY OF JAPANESE GLASS". GLASS ART SOCIETY. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ William Wayne Farris,Population, Disease, and Land in Early Japan, 645–900, Harvard University Asia Center, 1995 p. 3

- ^ a b c d Henshall, pp. 11–15, 227.

- ^ Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan", Asian Perspectives, Fall 2007, pp. 241, 431.

- ^ John C. Maher, 'North Kyushu Creole: A Language Contact Model for the Origins of Japanese,' in Donald Denoon (ed.), Multicultural Japan: Palaeolithic to Postmodern, Cambridge University Press (1996 ) 2001 pp. 31–45, 40.

- ^ a b c d e f Henshall, 15-17, 22, 228.

- ^ a b c d Totman, 102-104.

- ^ a b c Weston, 126-129, 257.

- ^ a b Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan Volume One (New York: Kodansha, 1983), 104-107.

- ^ a b Perez, 18-19.

- ^ Totman, 106.

- ^ a b Henshall, 18-19, 25.

- ^ Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan", Asian Perspectives, Fall 2007, 445.

- ^ a b c Sansom, 54-57, 68.

- ^ a b Totman, 108, 112-115.

- ^ Henshall, 5-6, 24-26.

- ^ Keene 1999 : 33, 65, 67-69, 74, 89.

- ^ Totman, 129-130, 140-143.

- ^ Farris, 59.

- ^ Sansom, 99.

- ^ a b c d e f Henshall, 26, 28-33.

- ^ Sansom, 130-131.

- ^ Keene 1999 : 477-478.

- ^ Totman, 183.

- ^ a b c Totman, 149-153.

- ^ Perez, 25-26.

- ^ a b c d e Henshall, 34-40.

- ^ Weston, 137.

- ^ Perez, 28-29.

- ^ Sansom, 441-442.

- ^ a b Farris, 140-151.

- ^ Perez, 32-33.

- ^ a b c d Henshall, 41-45.

- ^ a b c Perez, 37-46.

- ^ a b Totman, 234–241.

- ^ Farris, 166.

- ^ Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan Volume One (New York: Kodansha, 1983), 126.

- ^ a b c Henshall, 46-50.

- ^ a b Perez, 48-52.

- ^ Weston, 141-143.

- ^ Farris, 192.

- ^ Hane, 133.

- ^ a b c d e f g Henshall, 54-67.

- ^ a b c Perez, 62-63, 72.

- ^ Totman, 297.

- ^ McClain, 26-27.

- ^ Totman, 308.

- ^ Perez, 60.

- ^ Perez, 57, 63-64.

- ^ Totman, 317-322, 335-337.

- ^ Perez, 67.

- ^ Hane, 171-182.

- ^ Totman, 335-337, 367-370.

- ^ a b c d Henshall, 68-71.

- ^ McClain, 120-124, 128-129.

- ^ Richard Sims, Japanese Political History since the Meiji Renovation, 1868-2000 (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 8-11.

- ^ a b Perez, 79-81.

- ^ Hane, 168-169.

- ^ Perez, 85-86.

- ^ Totman, 380-385.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Henshall, 75-101, 217.

- ^ Totman, 458-459.

- ^ Totman, 401, 460-461.

- ^ Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (New York: Harper Collins, 2000), 27-36.

- ^ McClain, 161.

- ^ Perez, 98.

- ^ Totman, 422-425.

- ^ Perez, 115-123.

- ^ Perez, 102-103.

- ^ Janet Hunter, Concise Dictionary of Modern Japanese History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 3.

- ^ Totman, 403-404, 431.

- ^ a b Perez, 134-136.

- ^ a b Totman, 440-442, 452-454.

- ^ a b Henshall, 108-111.

- ^ McClain, 328-332, 389-390.

- ^ Totman, 471, 488-489.

- ^ a b c d Totman, 576, 580-584.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Henshall, 112-138.

- ^ Richard Sims, Japanese Political History since the Meiji Renovation, 1868-2000 (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 139, 179-185.

- ^ Perez, 139-140.

- ^ Totman, 476-477.

- ^ McClain, 415-416, 422.

- ^ McClain, 454.

- ^ Weston, 201-203.

- ^ Totman, 553-556.

- ^ Richard Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire (New York: Random House, 1999), 28-29.

- ^ Totman, 560-563.

- ^ Perez, 147-148.

- ^ a b c d Henshall, 149-158.

- ^ Perez, 149-150.

- ^ Totman, 569-573.

- ^ a b c d e Henshall, 159-174.

- ^ Perez, 159-163.

- ^ Perez, 169.

- ^ McClain, 590-595.

- ^ Kazuhiko Togo, Japan's Foreign Policy 1945-2003: The Quest for a Proactive Policy (Boston: Brill, 2005), 162-163, 234-236.

- ^ Kazuhiko Togo, Japan's Foreign Policy 1945-2003: The Quest for a Proactive Policy (Boston: Brill, 2005), 126-128.

- ^ a b c d Henshall, 181-192.

- ^ McClain, 600-602.

- ^ "Japan election: Shinzo Abe and LDP in sweeping win - exit poll". BBC News. December 16, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Totman, 677-680.

Select works cited

- Farris, William Wayne, Japan to 1600: A Social and Economic History (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009)

- Hane, Mikiso, Premodern Japan: A Historical Survey (Boulder: Westview Press, 1991)

- Henshall, K. (2012). A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230346628.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keene, Donald (1999). A History of Japanese Literature, Vol. 1: Seeds in the Heart — Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11441-7.

- McClain, James L., Japan: A Modern History (New York: WW Norton & Co., 2002)

- Perez, Louis G., The History of Japan (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1998)

- Sansom, George, A History of Japan to 1334 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1958)

- Totman, Conrad, A History of Japan (Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell, 2005)

- Weston, Mark, Giants of Japan (New York: Kodansha, 2002)

Further reading

- Akagi, Roy Hidemichi, Japan's Foreign Relations, 1542-1936: A Short History (Tokyo: The Hokuseido Press, 1936)

- Allinson, Gary D., The Columbia Guide to Modern Japanese History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999)

- Allinson, Gary D., Japan's Postwar History (London: UCL Press, 1997)

- Beasley, William G., The Modern History of Japan (New York: Praeger, 1963)

- Beasley, William G, Japanese Imperialism, 1894–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987)

- Clement, Ernest Wilson, A Short History of Japan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1915)

- Cullen, Louis, A History of Japan, 1582–1941: Internal and External Worlds (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003)

- Edgerton, Robert B., Warriors of the Rising Sun: A History of the Japanese Military (New York: Norton, 1997)

- Friday, Karl F., ed., Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850 (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2012)

- Gordon, Andrew, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003)

- Hall, John Whitney, Japan: From Prehistory to Modern Times (New York: Delacorte Press, 1970)

- Hane, Mikiso, Modern Japan: A Historical Survey (Boulder : Westview Press, 1986)

- Huffman, James L., ed., Modern Japan: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998)

- Hunter, Janet, Concise Dictionary of Modern Japanese History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984)

- Jansen, Marius, The Making of Modern Japan (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000)

- Perez, Louis G., ed., Japan at War : An Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2013)

- Reischauer, Edwin O., Japan: The Story of a Nation (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970)

- Stockwin, JAA, Dictionary of the Modern Politics of Japan (New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003)

- Tipton, Elise, Modern Japan: A Social and Political History (New York: Routledge, 2002)

- Varley, Paul. Japanese Culture. 4th Edition. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. 2000)