Honduras

15°00′N 86°30′W / 15.000°N 86.500°W

Republic of Honduras República de Honduras | |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

| Anthem: "Himno Nacional de Honduras" "National Anthem of Honduras" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Tegucigalpa |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Ethnic groups ([1]) |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Presidential republic |

| Juan Orlando Hernández | |

| Ricardo Álvarez Arias | |

| Mauricio Oliva | |

| Legislature | National Congress |

| Independence | |

• Declaredb from Spain | 15 September 1821 |

• Declared from the First Mexican Empire | 1 July 1823 |

• Declared, as Honduras, from the Federal Republic of Central America | 5 November 1838 |

| Area | |

• Total | 112,492 km2 (43,433 sq mi) (102nd) |

| Population | |

• 2010 estimate | 8,249,574 (94th) |

• 2007 census | 7,529,403 |

• Density | 64/km2 (165.8/sq mi) (128th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | $40.983 billion[2] |

• Per capita | $4,959[2] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | $19.567 billion[2] |

• Per capita | $2,368[2] |

| Gini (1992–2007) | 55.3[3] high inequality |

| HDI (2014) | medium (131st) |

| Currency | Lempira (HNL) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +504 |

| ISO 3166 code | HN |

| Internet TLD | .hn |

| |

Population estimates explicitly take into account the effects of excess mortality due to AIDS; this can result in lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality and death rates, lower population and growth rates, and changes in the distribution of population by age and sex than would otherwise be expected, as of July 2007. | |

Honduras (/hɒnˈdʊərəs/ ; Spanish: [onˈduɾas]), officially the Republic of Honduras (Spanish: República de Honduras), is a republic in Central America. It was at times referred to as Spanish Honduras to differentiate it from British Honduras, which became the modern-day state of Belize.[5] Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, and to the north by the Gulf of Honduras, a large inlet of the Caribbean Sea.

Honduras was home to several important Mesoamerican cultures, most notably the Maya, prior to being conquered by Spain in the sixteenth century. The Spanish introduced Roman Catholicism and the now predominant Spanish language, along with numerous customs that have blended with the indigenous culture. Honduras became independent in 1821 and has since been a republic, although it has consistently endured much social strife and political instability, remaining one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere. Honduras has the world's highest murder rate.[6]

Honduras spans an area of about 112,492 km2 and has a population exceeding 8 million. Its northern portions are part of the Western Caribbean Zone, as reflected in the area's demographics and culture. Honduras is known for its rich natural resources, including various minerals, coffee, tropical fruit, and sugar cane, as well as for its growing textiles industry, which serves the international market.

Etymology

Honduras literally means "depths" in Spanish. The name could either refer to the bay of Trujillo as an anchorage, fondura in the Leonese dialect of Spanish, or to Columbus's alleged quote that "Gracias a Dios que hemos salido de esas Honduras" ("Thank God we have departed from those depths").[7][8][9]

It was not until the end of the 16th century that Honduras was used for the whole province and prior to 1580, Honduras only referred to the eastern part of the province, and Higueras referred to the western part.[9] Another early name is Guaymuras, revived as the name for the political dialogue in 2009 that took place in Honduras as opposed to Costa Rica. [10]

History

Pre-colonial period

In pre-Columbian times, modern Honduras was part of the Mesoamerican cultural area. In the west, the Maya civilization flourished for hundreds of years. The dominant state within Honduras's borders was that based in Copán. Copán fell with the other Lowland centres during the conflagrations of the Terminal Classic during the 9th century. The Maya of this civilization survive in western Honduras as the Ch'orti', isolated from their Choltian linguistic peers to the west.

Remains of other Pre-Columbian cultures are found throughout the country. Archaeologists have studied sites such as Naco and La Sierra in the Naco Valley, Los Naranjos on Lake Yojoa, Yarumela in the Comayagua Valley, La Ceiba and Salitron Viejo (both now under the Cajon Dam reservoir), Selin Farm and Cuyamel in the Aguan valley, Cerro Palenque, Travesia, Curruste, Ticamaya, Despoloncal in the lower Ulua river valley, and many others.

Spanish conquest (1524)

On his fourth and the final voyage to the New World in 1502, Christopher Columbus landed near the modern town of Trujillo, in the vicinity of the Guaimoreto Lagoon and became the first European to visit the Bay Islands on the coast of Honduras.[11] On 30 July 1502 Columbus sent his brother Bartholomew to explore the islands and Bartholomew encountered a Mayan trading vessel from Yucatán, carrying well-dressed Maya and a rich cargo.[12] Bartholomew's men stole whatever cargo they wanted and kidnapped the ship's elderly captain to serve as an interpreter[13] in what was the first recorded encounter between the Spanish and the Maya.[14]

In March 1524, Gil González Dávila became the first Spaniard to enter Honduras as a conquistador.[15][16] followed by Hernán Cortés, bringing forces down from Mexico. Much of the conquest was done in the following two decades, first by groups loyal to Cristóbal de Olid, and then by those loyal of Francisco Montejo but most particularly by those following Alvarado. In addition to Spanish resources, the conquerors relied heavily on armed forces from Mexico—Tlaxcalans and Mexica armies of thousands who lived on in the region as garrisons.

Resistance to conquest was led in particular by Lempira, and many regions in the north never fell to the Spanish, notably the Miskito Kingdom. After the Spanish conquest, Honduras became part of Spain's vast empire in the New World within the Kingdom of Guatemala. Trujillo and Gracias were the first city-capitals. The Spanish ruled the region for approximately three centuries.

Spanish Honduras (1524–1821)

Honduras was organized as a province of the "Kingdom of Guatemala" and the capital was fixed, first at Trujillo on the Atlantic coast, and later at Comayagua, and finally at Tegucigalpa in the central part of the country.

Silver mining was a key factor in the Spanish conquest and settlement of Honduras.[17] Initially the mines were worked by local people through the encomienda system, but as disease and resistance made this less available, slaves from other parts of Central America were brought in, and following the end of the local slave trading period at the end of the sixteenth century, African slaves, mostly from Angola were obtained.[18] After about 1650, very few slaves or other outside workers arrived in Honduras.

Although the Spanish conquered the southern or Pacific portion of Honduras fairly quickly they were less successful in the northern or Atlantic side. They managed to found a few towns along the coast, at Puerto Caballos and Trujillo in particular, but failed to conquer the eastern portion of the region and many pockets of independent indigenous people as well. The Miskito Kingdom, located in the northeast was particularly effective in resisting conquest. The Miskitos in turn found support from northern European privateers, pirates and especially the British (formerly English) colony of Jamaica, which placed much of it under their protection after 1740.

Independence (1821)

Honduras became independent from Spain in 1821 and was for a time part of the First Mexican Empire until 1823 when it became part of the United Provinces of Central America federation. Since 1838, it has been an independent republic and held regular elections.

Comayagua was the capital of Honduras until 1880, when it moved to Tegucigalpa.

In the decades of 1840 and 1850 Honduras participated in several failed attempts to restore Central American unity, such as the Confederation of Central America (1842–1845), the covenant of Guatemala (1842), the Diet of Sonsonate (1846), the Diet of Nacaome (1847) and National Representation in Central America (1849–1852).

Although Honduras eventually adopted the name Republic of Honduras, the unionist ideal never waned, and Honduras was one of the Central American countries that pushed hardest for the policy of regional unity.

Since independence, nearly 300 small internal rebellions and civil wars have occurred in the country, including some changes of government.

Neoliberal policies favoring international trade and investment began in the 1870s, and soon foreign interests became involved first in shipping, especially tropical fruit (most notably bananas) from the north coast, and then in railway building. In 1888, a projected railroad line from the Caribbean coast to the capital, Tegucigalpa, ran out of money when it reached San Pedro Sula, resulting in its growth into the nation's main industrial center and second largest city.

20th century

In the late nineteenth century, United States-based infrastructure and fruit-growing companies received substantial land and exemptions to develop the northern regions. As a result, thousands of workers came to the north coast to work in the banana plantations and the other industries that grew around the export industry. The banana exporting companies, dominated by Cuyamel Fruit Company (until 1930), United Fruit Company, and Standard Fruit Company, built an enclave economy in northern Honduras, controlling infrastructure and creating self-sufficient, tax exempt sectors that contributed relatively little to economic growth. Honduras saw insertion of American troops in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924 and 1925.[19] In 1904 writer O. Henry coined the term "Banana republic" to describe Honduras.[20]

In addition to drawing many Central American workers to the north, the fruit companies also encouraged immigration of workers from the English-speaking Caribbean, notably Jamaica and Belize, who introduced an African-descended, English speaking and largely Protestant population into the country, though many left after changes in the immigration law in 1939.[21]

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Honduras joined the Allied Nations on 8 December 1941. Along with twenty-five other governments, Honduras signed the Declaration by United Nations on 1 January 1942.

Constitutional crises in the 1940s led to reforms in the 1950s, and as a result of one such reform, workers were given permission to organize, which led to a general strike in 1954 that paralyzed the northern part of the country for more than two months, but which led to more general reforms. In 1963 a military coup was mounted against the democratically elected president Ramón Villeda Morales.

In 1969 Honduras and El Salvador fought what would become known as the Football War. There had been border tensions between the two countries after Oswaldo López Arellano, a former president of Honduras, blamed the deteriorating economy on the large number of immigrants from El Salvador. From that point on the relationship between the two neighbours grew acrimonious and reached a low when El Salvador met Honduras for a three-round football elimination match as a preliminary to the World Cup.[22]

Tensions escalated and on 14 July 1969, the Salvadoran army launched an attack on the Honduran army. The Organization of American States negotiated a cease-fire which took effect on 20 July and brought about a withdrawal of Salvadoran troops in early August.[22] Contributing factors to the conflict were a boundary dispute and the presence of thousands of Salvadorans living in Honduras illegally. After the week-long war as many as 130,000 Salvadoran immigrants were expelled.[23]

Hurricane Fifi caused severe damage while skimming the northern coast of Honduras on 18 and 19 September 1974. Melgar Castro (1975–78) and Paz Garcia (1978–82) largely built the current physical infrastructure and telecommunications system of Honduras.[24]

In 1979, the country returned to civilian rule. A constituent assembly was popularly elected in April 1980 and general elections were held in November 1981. A new constitution was approved in 1982 and the PLH government of Roberto Suazo assumed power. Roberto Suazo won the elections with a promise to carry out an ambitious program of economic and social development in Honduras in order to tackle the country's recession. President Roberto Suazo Cordoba launched ambitious social and economic development projects, sponsored by American development aid. Honduras became host to the largest Peace Corps mission in the world, and nongovernmental and international voluntary agencies proliferated. The Peace Corps withdrew its volunteers in 2012 citing safety concerns.[25]

During the early 1980s, the United States established a continuing military presence in Honduras with the purpose of supporting U.S. Government support to El Salvador, the Contra guerrillas fighting the Nicaraguan government, and also developed an air strip and a modern port in Honduras. Though spared the bloody civil wars wracking its neighbors, the Honduran army quietly waged a campaign against Marxist-Leninist militias such as Cinchoneros Popular Liberation Movement, notorious for kidnappings and bombings,[26] and many non-militants. The operation included a CIA-backed campaign of extrajudicial killings by government-backed units, most notably Battalion 316.[27]

In 1998, Hurricane Mitch caused such massive and widespread destruction that former Honduran President Carlos Roberto Flores claimed that fifty years of progress in the country had been reversed. Mitch destroyed about 70% of the crops and an estimated 70–80% of the transportation infrastructure, including nearly all bridges and secondary roads. Across the country, 33,000 houses were destroyed, an additional 50,000 damaged, some 5,000 people killed, 12,000 more injured – for a total loss estimated at $3 billion USD.[28]

21st century

The 2008 Honduran floods were severe and around half the country's roads were damaged or destroyed as a result.[29]

In 2009, a constitutional crisis culminated in a transfer of power from the president to the head of Congress.[30][31][32]

Countries around the world, the OAS, and the UN formally and unanimously condemned the action as a coup d'état and refused to recognize the de facto government, though a document submitted to the United States Congress declared the coup to be legal according to the opinion of the lawyers consulted by the Library of Congress.[30][33][34] The Honduran Supreme Court ruled the proceedings to be legal. The government that followed the de facto government, established a "truth and reconciliation commission", Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación, which after more than a year of research and debate concluded the ousting to be a coup d'état "to the executive power", illegal in its opinion.[35][36][37]

Geography

The north coast of Honduras borders the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean lies south through the Gulf of Fonseca. Honduras consists mainly of mountains, with narrow plains along the coasts. A large undeveloped lowland jungle, La Mosquitia lies in the northeast, and the heavily populated lowland Sula valley in the northwest. In La Mosquitia lies the UNESCO world-heritage site Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, with the Coco River which divides Honduras from Nicaragua.

The Islas de la Bahía and the Swan Islands are off the north coast. Misteriosa Bank and Rosario Bank, 130 to 150 km (80–93 miles) north of the Swan Islands, fall within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of Honduras.

Natural resources include timber, gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, iron ore, antimony, coal, fish, shrimp, and hydropower.

Climate

The climate varies from tropical in the lowlands to temperate in the mountains. The central and southern regions are relatively hotter and less humid than the northern coast.

Ecology

The region is considered a biodiversity hotspot because of the numerous plant and animal species found there and like other countries in the region, contains vast biological resources. Honduras hosts more than 6,000 species of vascular plants, of which 630 (described so far) are orchids; around 250 reptiles and amphibians, more than 700 bird species, and 110 mammal species, of which half are bats.[38]

In the northeastern region of La Mosquitia lies the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, a lowland rainforest which is home to a great diversity of life. The reserve was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites List in 1982.

Honduras has rain forests, cloud forests (which can rise up to nearly three thousand meters above sea level), mangroves, savannas and mountain ranges with pine and oak trees, and the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System. In the Bay Islands there are bottlenose dolphins, manta rays, parrot fish, schools of blue tang and whale shark.

Environmental issues

Deforestation resulting from logging is rampant in Olancho Department. The clearing of land for agriculture is prevalent in the largely undeveloped La Mosquitia region, causing land degradation and soil erosion.

Lake Yojoa, which is Honduras' largest source of fresh water, is polluted by heavy metals produced from mining activities. Some rivers and streams are also polluted by mining.[citation needed]

Government and politics

Honduras is governed within a framework of a presidential representative democratic republic. The President of Honduras is both head of state and head of government. Executive power is exercised by the Honduran government. Legislative power is vested in the National Congress of Honduras. The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

The National Congress of Honduras (Congreso Nacional) has 128 members (diputados), elected for a four-year term by proportional representation. Congressional seats are assigned the parties' candidates on a departmental basis in proportion to the number of votes each party receives.[1]

Political culture

In 1963, a military coup succeeded against the democratically elected president, Ramón Villeda Morales. This event started a string of military governments which held power almost uninterrupted until 1981, when Suazo Córdova (LPH) was elected president and Honduras changed from a military authoritarian regime.

Today, the party system is dominated by the conservative National Party of Honduras (Partido Nacional de Honduras: PNH) and the liberal Liberal Party of Honduras (Partido Liberal de Honduras: PLH). Since 1981 Honduras has had six Liberal Party presidents: Roberto Suazo Córdova, José Azcona del Hoyo, Carlos Roberto Reina, Carlos Roberto Flores, Manuel Zelaya and Roberto Micheletti, and four National Party Presidents: Rafael Leonardo Callejas Romero, Ricardo Maduro, Porfirio Lobo Sosa and Juan Orlando Hernández.

The current Honduras president is Juan Orlando Hernández, who assumed office on 27 January 2014.

Foreign relations

Honduras and Nicaragua had tense relations throughout 2000 and early 2001 due to a boundary dispute off the Atlantic coast. Nicaragua imposed a 35% tariff against Honduran goods due to the dispute.

In June 2009, Honduran President Manuel Zelaya was ousted in a coup d'état and taken to neighboring Costa Rica. Like several other Latin American nations, Mexico temporarily severed diplomatic relations with Honduras. In July 2010, full diplomatic relations were once again re-established.[39]

The United States maintains a small presence at a Honduran military base; the two countries conduct joint peacekeeping, counter-narcotics, humanitarian, disaster relief, and civic action exercises. U.S. troops conduct and provide logistics support for a variety of bilateral and multilateral exercises—medical, engineering, peacekeeping, counter-narcotics, and disaster relief. The United States is Honduras' chief trading partner.[24]

Military

Honduras has a modest military with Western equipment.

Administrative divisions

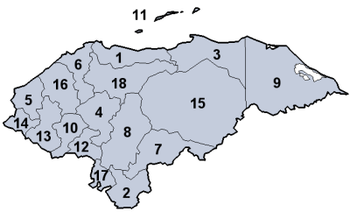

Honduras is divided into 18 departments. The capital city is Tegucigalpa in the Central District within the department of Francisco Morazán.

- Atlántida

- Choluteca

- Colón

- Comayagua

- Copán

- Cortés

- El Paraíso

- Francisco Morazán

- Gracias a Dios

- Intibucá

- Islas de la Bahía

- La Paz

- Lempira

- Ocotepeque

- Olancho

- Santa Bárbara

- Valle

- Yoro

Economy

Economic growth in the last few years has averaged 7% a year, one of the highest rates in Latin America (2010). In 2010 50% of the population were below the poverty line.[40] It is estimated that there are more than 1.2 million people who are unemployed, the rate of unemployment standing at 27.9%. According to the Human Development Index, Honduras is the sixth poorest/least developed country in Latin America, after Haiti, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Guyana, and Bolivia.

Honduras was declared one of the heavily indebted poor countries by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and became eligible for debt relief in 2005.

The government operates both the electricity (ENEE) and land-line telephone services (HONDUTEL), as ENEE receives heavy subsidies for its chronic financial problems. HONDUTEL, however, is no longer a monopoly, as the telecommunication sector was opened to private sector on 25 December 2005, as was required under the CAFTA. The price of petroleum is controlled, and the Congress often ratifies temporary price regulations for basic commodities.

Gold, silver, lead and zinc are mined.[41]

The Honduran lempira is the currency.

In 2005 Honduras signed the CAFTA, the free trade agreement with the United States. In December 2005, Puerto Cortes, the main seaport in Honduras, was included in the U.S. Container Security Initiative.[42]

In 2006 the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Energy announced the first phase of the Secure Freight Initiative, an unprecedented effort to build upon existing port security measures by enhancing the U.S. government’s authority to scan containers from overseas for nuclear and radiological materials to better assess the risk of inbound containers. The initial phase of Secure Freight involves the deployment of nuclear detection and other devices to six foreign ports: Port Qasim in Pakistan; Puerto Cortes in Honduras; Southampton in the United Kingdom; Port Salalah in Oman; Port of Singapore; and the Gamman Terminal at Port Busan in Korea. Since early 2007, containers from these ports have been scanned for radiation and other risk factors before they are allowed to depart for the United States.[43]

To enhance the economy, in 2012 the Honduran government signed a memorandum of understanding with a group of international investors to build a zone (city) with their own laws, tax system, judiciary and police, but the opponents tried to lodge a suit at the supreme court about it ('state within a state').[44]

Energy

About half of the electricity sector in Honduras is privately owned. The remaining generation capacity is run by ENEE (Empresa Nacional de Energía Eléctrica). Key challenges in the sector are:

- How to finance investments in generation and transmission in the absence of either a financially healthy utility or of concessionary funds by external donors for these types of investments;

- How to re-balance tariffs, cut arrears and reduce commercial losses – including electricity theft – without fostering social unrest; and

- How to reconcile environmental concerns with the government's objective to build two new large dams and associated hydropower plants.

- How to improve access in rural areas.

Transport

Infrastructure for transportation in Honduras consists of: 699 km of railways; 13,603 km of roadways;[1] seven ports and harbors;[citation needed] and 112 airports altogether (12 Paved, 100 unpaved).[1] Responsibility for policy in the transport sector rests with the Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Housing (SOPRTRAVI after its Spanish acronym).

Water supply and sanitation

Water supply and sanitation in Honduras varies greatly from urban centers to rural villages. Larger population centers generally have modernized water treatment and distribution systems, however water quality is often poor because of lack of proper maintenance and treatment. Rural areas generally have basic drinking water systems with limited capacity for water treatment. Many urban areas have sewer systems in place for the collection of wastewater, with proper treatment of wastewater being scarce. In rural areas sanitary facilities are generally limited to latrines and basic septic pits.

Water and sanitation services were historically provided by Servicio Autonomo de Alcantarillas y Aqueductos (SANAA). In 2003, the government enacted a new "water law" which called for the decentralization of water services. With the 2003 law, local communities have the right and responsibility to own, operate, and control their own drinking water and wastewater systems. Since passage of the new law, many communities have joined together to address water and sanitation issues on a regional basis.

Many national and international non-government organizations have a history of working on water and sanitation projects in Honduras. International groups include, but are not limited to, the Red Cross, Water 1st, Rotary Club, Catholic Relief Services, Water for People, EcoLogic Development Fund, CARE, CESO-SACO, Engineers Without Borders – USA, Flood The Nations, SHH, Global Brigades, and Agua para el Pueblo in partnership with AguaClara at Cornell University.

In addition, many government organizations working on projects include: the European Union, USAID, the Army Corps of Engineers, Cooperacion Andalucia, the government of Japan, and many others.

Demographics

Honduras had a population of 8,143,564 in 2011.[1] The proportion of the population aged below 15 in 2010 was 36.8%, 58.9% were aged between 15 and 65 years of age, and 4.3% were aged 65 years or older.[45]

Since 1975, emigration from Honduras has accelerated as economic migrants and political refugees sought a better life elsewhere. A majority of expatriate Hondurans live in the United States. A 2012 US State Department estimates suggested there are between 800,000 and 1 million Hondurans living in the United States, nearly 15% of the Honduran domestic population.[24] The large uncertainty is due to the substantial number of Hondurans living illegally in the United States. The 2010 U.S. Census counted 617,392 Hondurans in the United States, up from 217,569 in 2000.[46]

Ethnic groups

The population is 90% Mestizo (mixed Amerindian and European), 7% Amerindian, 2% Black, 1% White.[1]

Languages

Spanish, Honduran Sign Language, Garifuna, Bay Islands Creole English, Mískito, Sumu, Pech, Jicaque, Ch’orti’, Lenca (extinct).

Urban areas

These are the top 10 most populated cities in Honduras as per the 2010 estimates.[47]

| Rank | City/Town | Population | Department |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tegucigalpa | 1,126,534 | Francisco Morazán |

| 2 | San Pedro Sula | 638,259 | Cortés |

| 3 | Choloma | 222,828 | Cortés |

| 4 | La Ceiba | 174,006 | Atlántida |

| 5 | El Progreso | 131,125 | Yoro |

| 6 | Choluteca | 93,598 | Choluteca |

| 7 | Comayagua | 75,281 | Comayagua |

| 8 | Puerto Cortés | 60,751 | Cortés |

| 9 | La Lima | 59,030 | Cortés |

| 10 | Danlí | 56,968 | El Paraíso |

Religion

Although most Hondurans are nominally Roman Catholic (which would be considered the main religion), membership in the Roman Catholic Church is declining while membership in Protestant churches is increasing. The International Religious Freedom Report, 2008, notes that a CID Gallup poll reported that 51.4% of the population identified themselves as Catholic, 36.2% as evangelical Protestant, 1.3% claiming to be from other religions, including Muslims, Buddhists, Jews, Rastafarians, etc. and 11.1% do not belong to any religion or unresponsive. Customary Catholic church tallies and membership estimates 81% Catholic where the priest (in more than 185 parishes) is required to fill out a pastoral account of the parish each year.[48][49]

The CIA Factbook lists Honduras as 97% Catholic and 3% Protestant.[1] Commenting on statistical variations everywhere, John Green of Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life notes that: "It isn't that ... numbers are more right than [someone else's] numbers ... but how one conceptualizes the group."[50] Often people attend one church without giving up their "home" church. Many who attend evangelical megachurches in the US, for example, attend more than one church.[51] This shifting and fluidity is common in Brazil where two-fifths of those who were raised evangelical are no longer evangelical and Catholics seem to shift in and out of various churches, often while still remaining Catholic.[52]

Most pollsters suggest an annual poll taken over a number of years would provide the best method of knowing religious demographics and variations in any single country. Still, in Honduras are thriving Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, Seventh-day Adventist, Lutheran, Latter-day Saint (Mormon) and Pentecostal churches. There are Protestant seminaries. The Catholic Church, still the only "church" that is recognized, is also thriving in the number of schools, hospitals, and pastoral institutions (including its own medical school) that it operates. Its archbishop, Oscar Andres Rodriguez Maradiaga, is also very popular, both with the government, other churches, and in his own church. Practitioners of the Buddhist, Jewish, Islamic, Bahá'í, Rastafari and indigenous denominations and religions exist.[53]

Health

The fertility rate is approximately 3.7 per woman.[54] The under-five mortality rate is at 40 per 1,000 live births.[54] The health expenditure was US$ (PPP) 197 per person in 2004.[54] There are about 57 physicians per 100,000 people.[54]

Education

About 83.6% of the population are literate and the net primary enrollment rate was 94% in 2004.[54] However, in 2007 the primary school completion rate was reported to be 40%.[citation needed] Honduras has bilingual (Spanish and English) and even trilingual (Spanish with English, Arabic, and/or German) schools and numerous universities.[55]

The university is ruled by National Autonomous University of Honduras which have centers in the most important cities in Honduras.

Crime

In 2012, Honduras had a murder rate of 90.4 per 100,000 population. There were a total of 7,172 murders in Honduras in 2012. This is the highest murder rate in the world, followed by Venezuela (with 53.7 murders per 100,000 people).[56]

Culture

Creative endeavors

The most renowned Honduran painter is Jose Antonio Velásquez. Other important painters include Carlos Garay, and Roque Zelaya. Some of Honduras' most notable writers are Lucila Gamero de Medina, Froylan Turcios, Ramón Amaya Amador and Juan Pablo Suazo Euceda, Marco Antonio Rosa, Roberto Sosa, Eduardo Bähr, Amanda Castro, Javier Abril Espinoza, Teófilo Trejo, and Roberto Quesada.

Hondurans are often referred to as Catracho or Catracha (fem) in Spanish. The word was coined by Nicaraguans and derives from the last name of the Spanish Honduran General Florencio Xatruch, who, in 1857, led Honduran armed forces against an attempted invasion by North American adventurer William Walker. The nickname is considered complimentary, not derogatory.

The José Francisco Saybe theater in San Pedro Sula is home to the Círculo Teatral Sampedrano (Theatrical Circle of San Pedro Sula)

Cuisine

Honduran cuisine is a fusion of indigenous Lenca cuisine, Spanish cuisine, Caribbean cuisine and African cuisine. There are also dishes from the Garifuna people. Coconut and coconut milk are featured in both sweet and savory dishes. Regional specialties include fried fish, tamales, carne asada and baleadas.

Other popular dishes include: meat roasted with chismol and carne asada, chicken with rice and corn, and fried fish with pickled onions and jalapeños. In the coastal areas and in the Bay Islands, seafood and some meats are prepared in many ways, some of which include coconut milk.

Among the soups the Hondurans enjoy are bean soup, mondongo soup (tripe soup), seafood soups and beef soups. Generally all of these soups are mixed with plantains, yuca, and cabbage, and served with corn tortillas.

Other typical dishes are the montucas or corn tamale, stuffed tortillas, and tamales wrapped in plantain leaves. Also part of Honduran typical dishes is an abundant selection of tropical fruits such as papaya, pineapple, plum, sapote, passion fruit and bananas which are prepared in many ways while they are still green.

Media

At least half of the Honduran households have at least one television. Public television has a far smaller role than in most other countries. Honduras' main newspapers are La Prensa, El Heraldo, La Tribuna and Diario Tiempo. The official newspaper is La Gaceta.

Music

Punta is the main music of Honduras, with other sounds such as Caribbean salsa, merengue, reggae, and reggaeton all widely heard especially in the North, to Mexican rancheras heard in the interior rural part of the country.

Celebrations

Some of Honduras' national holidays include Honduras Independence Day on 15 September and Children's Day or Día del Niño, which is celebrated in homes, schools and churches on 10 September; on this day, children receive presents and have parties similar to Christmas or birthday celebrations. Some neighborhoods have piñatas on the street. Other holidays are Easter, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Day of the Soldier (3 October to celebrate the birth of Francisco Morazán), Christmas, El Dia de Lempira on 20 July,[57] and New Year's Eve.

Honduras Independence Day festivities start early in the morning with marching bands. Each band wears different colors and features cheerleaders. Fiesta Catracha takes place this same day: typical Honduran foods such as beans, tamales, baleadas, cassava with chicharron, and tortillas are offered.

On Christmas Eve people reunite with their families and close friends to have dinner, then give out presents at midnight. In some cities fireworks are seen and heard at midnight. On New Year's Eve there is food and "cohetes", fireworks and festivities. Birthdays are also great events, and include the famous "piñata" which is filled with candies and surprises for the children invited.

La Feria Isidra is celebrated in La Ceiba, a city located in the north coast, in the second half of May to celebrate the day of the city's patron saint Saint Isidore. People from all over the world come for one week of festivities. Every night there is a little carnaval (carnavalito) in a neighborhood. On Saturday there is a big parade with floats and displays with people from many countries. This celebration is also accompanied by the Milk Fair, where many Hondurans come to show off their farm products and animals.

National symbols

The flag of Honduras is composed of three equal horizontal stripes, with the upper and lower ones being blue and representing the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea. The central stripe is white. It contains five blue stars representing the five states of the Central American Union. The middle star represents Honduras, located in the center of the Central American Union.

The coat of arms was established in 1945. It is an equilateral triangle, at the base is a volcano between three castles, over which is a rainbow and the sun shining. The triangle is placed on an area that symbolizes being bathed by both seas. Around all of this an oval containing in golden lettering: "Republic of Honduras, Free, Sovereign and Independent".

The "National Anthem of Honduras" is a result of a contest carried out in 1914 during the presidency of Manuel Bonilla. In the end, it was the poet Augosto C. Coello that ended up writing the anthem, with the participation of German composer Carlos Hartling writing the music. The anthem was officially adopted on 15 November 1915, during the presidency of Alberto Membreño. The anthem is composed of a choir and seven stroonduran.

The national flower is the famous orchid, Rhyncholaelia digbyana (formerly known as Brassavola digbyana), which replaced the rose in 1969. The change of the national flower was carried out during the administration of general Oswaldo López Arellano, thinking that Brassavola digbiana "is an indigenous plant of Honduras; having this flower exceptional characteristics of beauty, vigor and distinction", as the decree dictates it.

The national tree of Honduras was declared in 1928 to be simply "the Pine that appears symbolically in our Coat of Arms" (el Pino que figura simbólicamente en nuestro Escudo),[58] even though pines comprise a genus and not a species, and even though legally there's no specification as for what kind of pine should appear in the coat of arms either. Because of its commonality in the country, the Pinus oocarpa species has become since then the species most strongly associated as the national tree, but legally it is not so. Another species associated as the national tree is the Pinus caribaea.

The national mammal is the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), which was adopted as a measure to avoid excessive depredation. It is one of two species of deer that live in Honduras. The national bird of Honduras is the scarlet macaw (Ara macao). This bird was much valued by the pre-Columbian civilizations of Honduras.

Folklore

Legends and fairy tales are paramount within Honduran culture. Lluvia de Peces (Fish Rain) is an example of this. The legend of El Cadejo, La Llorona and La Ciguanaba (La Sucia) are also popular.

Sports

Football is the most popular Sport in Honduras. Information on all other Honduran sports related articles are below:

- Football in Honduras

- Honduran Football Federation

- Honduras national baseball team

- Honduras national football team

- Honduras national under-20 football team

- Honduras U-17 national football team

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Honduras". The World Fact Book. 5 January 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Honduras". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ 1992–2007: "Human Development Report 2009 – M Economy and inequality – Gini index". Human Development Report Office, United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 17 October 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Human Development Report 2015" (PDF). United Nations. 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ "Archeological Investigations in the Bay Islands, Spanish Honduras". Aboututila.com. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Parkinson, Charles (21 April 2014). "Latin America is World's Most Violent Region: UN". InSight Crime. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "History of Honduras — Timeline". Office of the Honduras National Chamber of Tourism. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Davidson traces it to Herrera. Historia General de los Hechos de los Castellanos. Vol. VI. Buenos Aires: Editorial Guarania. 1945–47. p. 24. ISBN 8474913322.

- ^ a b Davidson, William (2006). Honduras, An Atlas of Historical Maps. Managua: Fundacion UNO, Colección Cultural de Centro America Serie Historica, no. 18. p. 313. ISBN 978-99924-53-47-6.

- ^ Objetivos de desarrollo del milenio, Honduras 2010: tercer informe de país (PDF) (in Spanish). [Honduras]: Sistema de las Naciones Unidas en Honduras. 2010. ISBN 978-99926-760-7-3. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Columbus and the History of Honduras". Office of the Honduras National Chamber of Tourism. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Perramon 1986, p. 242; Clendinnen 2003, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Clendinnen 2003, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Vera, Robustiano, ed. (1899). Apuntes para la Historia de Honduras (PDF) (in Spanish). Santiago. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kilgore, Cindy; Moore, Alan. "Adventure Guide to Copan & Western Honduras". Hunter publishing. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

Spanish conquistadores did not become interested in colonization of Honduras until the 1520s when Cristobal de Olid the first European colony in Triunfo de la Cruz in1524. A previous expedition was headed by Gil Gonzalez Davila

- ^ Newson, Linda (October 1982). "Labour in the Colonial Mining Industry of Honduras". The Americas. 39 (2). Philadelphia: The Academy of American Franciscan History: 185. doi:10.2307/981334. JSTOR 981334.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Newson, Linda (December 1987). The Cost of Conquest: Indian Decline in Honduras Under Spanish Rule: Dellplain Latin American Studies, No. 20. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813372730.

- ^ Becker, Marc (2011). "History of U.S. Interventions in Latin America". Marc Becker. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Economist explains (21 November 2013). "Where did banana republics get their name?". economist.com. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Chambers, Glen (24 May 2010). Race Nation and West Indian Immigration to Honduras, 1890–1940. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0807135570.

- ^ a b "Wars of the World: Soccer War 1969". OnWar.com. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Merrill, Tim, ed. (1995). "War with El Salvador". Honduras. Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Relations With Honduras". United States Department of State. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Cuevas, Freddy; Gomez, Adriana (18 January 2012). "Peace Corps Honduras: Why are all the US volunteers leaving?". The Christian Science Monitor. Associated Press. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Cinchoneros Popular Liberation Movement". University of Maryland. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Cohn, Gary; Thompson, Ginger (15 June 1995). "A survivor tells her story". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Archived 2006-03-16 at the Wayback Machine.usgs.gov

- ^ "World: Americas Famine fears after floods". BBC News. 5 November 1998. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b "General Assembly condemns coup in Honduras" (Press release). United Nations. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "OAS Suspends Membership Of Honduras" (Press release). Organization of American States. 5 July 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "New Honduran leader sets curfew". BBC News. 29 June 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Shankman, Sabrina (6 October 2009). "De Facto government in Honduras pays Washington lobbyists $300,000 to sway U.S. opinion". Gov Monitor. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- ^ "US Congress report argues Zelaya's ousting was "legal and constitutional"". MercoPress. 25 September 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Honduras" (PDF). Seattle International Foundation. 18 July 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Honduras Truth Commission rules Zelaya removal was coup". BBC News. 7 July 2011.

- ^ Zebley, Julia (18 July 2011). "Honduras truth commission says coup against Zelaya was unconstitutional". JURIST.

- ^ "Honduran Biodiversity Database" (in Spanish). Honduras Silvestre. 1 August 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "México restablece las relaciones diplomáticas con Honduras". CNN (in Spanish). 31 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Honduras". World Bank. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Dan Oancea (January 2009), Mining in Central America. Mining.com Archived 2011-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Container Security Initiative Office of Field Operations: Operational Ports". U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2006.

- ^ "DHS and DOE Launch Secure Freight Initiative". DHS. 7 December 2006. Archived from the original on 6 March 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (6 September 2012). "Honduras to build new city with its own laws and tax system to attract investors". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2015.

- ^ "American Fact Finder: Allocation of Hispanic or Latino Origin". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Infos on The World Gazetteer Archived 2014-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Annuario Pontificio. Cardinal Secretary of State. 2009. ISBN 978-88209-81914.

- ^ Bunson, Matthew E.; Min, D. (4 November 2015). Catholic Almanac. Huntington, Ind.: Sunday Visitor Publishing. pp. 312–13. ISBN 978-1612789446.

- ^ Dart, John (16 June 2009). "How many in mainline Categories vary in surveys". The Christian Century. 126 (12): 13.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Associated Press, 13 June 2009, reported in several papers

- ^ Scalon, Maria Celi; Greeley, Andrew (18 August 2003). "Catholics and Protestants in Brazil". America. 189 (4): 14.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2008: Honduras". U.S. Department of State. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Human Development Report 2009 – Honduras". Hdrstats.undp.org. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Hondureños bilingües tendrán más ventajas". LaPrensa (in Spanish). 14 October 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Global Study on Homicide" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2013.

- ^ "Honduras This Week Online June 1999". Marrder.com. 9 December 1991. Archived from the original on 17 January 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Acuerdo No. 429, 14 de mayo de 1928.

External links

- Government of Honduras Template:Es icon

- Official Site of the Tourism Institute of Honduras (English)

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- "Honduras". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Honduras at University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries GovPubs

- Template:Dmoz

- Honduras profile from the BBC News

Wikimedia Atlas of Honduras

Wikimedia Atlas of Honduras- Honduran Biodiversity Database Template:Es icon

- Honduras Tips Travel Info (English)

- Honduras Weekly

- Travel and Tourism Info on Honduras (English)

- Humanitarian Aid in Honduras

- Answers.com

- Project Honduras

- Interactive Maps Honduras

- Key Development Forecasts for Honduras from International Futures