John Zerzan

John Zerzan | |

|---|---|

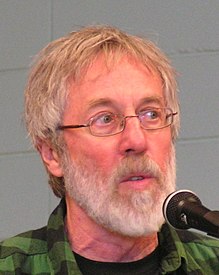

Zerzan lecturing at the 2010 Bay Area Anarchist Book Fair | |

| Born | August 10, 1943 (age 81) Salem, Oregon, United States |

| Alma mater | Stanford University San Francisco State University |

| Era | Contemporary philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Anarcho-primitivism, Post-left anarchy |

Main interests | Hunter-gatherer society, Civilization, alienation, symbolic culture, technology, mass society |

Notable ideas | Domestication of humans, rewilding |

John Zerzan (/ˈzɜːrzən/ ZUR-zən; born August 10, 1943) is an American anarchist and primitivist philosopher and author. His works criticize agricultural civilization as inherently oppressive, and advocate drawing upon the ways of life of hunter-gatherers as an inspiration for what a free society should look like. Some subjects of his criticism include domestication, language, symbolic thought (such as mathematics and art) and the concept of time.

His six major books are Elements of Refusal (1988), Future Primitive and Other Essays (1994), Running on Emptiness (2002), Against Civilization: Readings and Reflections (2005), Twilight of the Machines (2008), and Why hope? The Stand Against Civilization (2015).

| Part of a series on |

| Green anarchism |

|---|

|

Early life and education

Zerzan was born in Salem, Oregon. He received his bachelor's degree from Stanford University and later received a master's degree in History from San Francisco State University. He completed his coursework towards a PhD at the University of Southern California but dropped out before completing his dissertation. He is of Czech descent.

Zerzan's anarchism

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Zerzan's theories draw on Theodor Adorno's concept of negative dialectics to construct a theory of civilization as the cumulative construction of alienation. According to Zerzan, original human societies in paleolithic times, and similar societies today such as the !Kung and Mbuti, live a non-alienated and non-oppressive form of life based on primitive abundance and closeness to nature. Constructing such societies as an instructive comparison against which to denounce contemporary (especially industrial) societies, Zerzan uses anthropological studies from such societies as the basis for a wide-ranging critique of aspects of modern life. He portrays contemporary society as a world of misery built on the psychological production of a sense of scarcity and lack.[1] The history of civilization is the history of renunciation; what stands against this is not progress but rather the Utopia which arises from its negation.[2]

Zerzan is an anarchist philosopher, and is broadly associated with the philosophies of anarcho-primitivism, green anarchism, anti-civilisation, post-left anarchy, neo-luddism, and in particular the critique of technology.[3] He rejects not only the state, but all forms of hierarchical and authoritarian relations. "Most simply, anarchy means 'without rule.' This implies not only a rejection of government but of all other forms of domination and power as well."[4]

Zerzan's work relies heavily on a strong dualism between the "primitive" – viewed as non-alienated, wild, non-hierarchical, ludic, and socially egalitarian – and the "civilised" – viewed as alienated, domesticated, hierarchically organised and socially discriminatory. Hence, "life before domestication/agriculture was in fact largely one of leisure, intimacy with nature, sensual wisdom, sexual equality, and health."[5]

Zerzan's claims about the status of primitive societies are based on a certain reading of the works of anthropologists such as Marshall Sahlins and Richard B. Lee. Crucially, the category of primitives is restricted to pure hunter-gatherer societies with no domesticated plants or animals. For instance, hierarchy among Northwest Coast Native Americans whose main activities were fishing and foraging is attributed to their having domesticated dogs and tobacco.[5][6]

Zerzan calls for a "Future Primitive", a radical reconstruction of society based on a rejection of alienation and an embracing of the wild. "It may be that our only real hope is the recovery of a face-to-face social existence, a radical decentralization, a dismantling of the devouring, estranging productionist, high-tech trajectory that is so impoverishing."[4] The usual use of anthropological evidence is comparative and demonstrative – the necessity or naturality of aspects of modern western societies is challenged by pointing to counter-examples in hunter-gatherer societies. "Ever-growing documentation of human prehistory as a very long period of largely non-alienated life stands in sharp contrast to the increasingly stark failures of untenable modernity."[2] It is unclear, however, whether this implies a re-establishment of the literal forms of hunter-gatherer societies or a broader kind of learning from their ways of life in order to construct non-alienated relations.

Zerzan's political project calls for the destruction of technology. He draws the same distinction as Ivan Illich, between tools that stay under the control of the user, and technological systems that draw the user into their control. One difference is the division of labour, which Zerzan opposes. In Zerzan's philosophy, technology is possessed by an elite which automatically has power over other users; this power is one of the sources of alienation, along with domestication and symbolic thought.

Zerzan's typical method is to take a particular construct of civilisation (a technology, belief, practice or institution) and construct an account of its historical origins, what he calls its destructive and alienating effects and its contrasts with hunter-gatherer experiences. In his essay on number, for example, Zerzan starts by contrasting the "civilized" emphasis on counting and measuring with a "primitive" emphasis on sharing, citing Dorothy Lee's work on the Trobriand Islanders in support, before constructing a narrative of the rise of number through cumulative stages of state domination, starting with the desire of Egyptian kings to measure what they ruled.[7] This approach is repeated in relation to time,[8] gender inequality,[9] work,[10] technology,[11] art and ritual,[6] agriculture[12] and globalization.[13] Zerzan also writes more general texts on anarchist,[4] primitivist theory,[2][5] and critiques of "postmodernism".[14]

Zerzan was one of the editors of Green Anarchy, a controversial journal of anarcho-primitivist and insurrectionary anarchist thought. He is also the host of Anarchy Radio in Eugene on the University of Oregon's radio station KWVA. He has also served as a contributing editor at Anarchy Magazine and has been published in magazines such as AdBusters. He does extensive speaking tours around the world, and is married to an independent consultant to museums and other nonprofit organizations.

Political development

In 1966, Zerzan was arrested while performing civil disobedience at a Berkeley anti-Vietnam War march and spent two weeks in the Contra Costa County Jail. He vowed after his release never again to be willingly arrested. He attended events organized by Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters and was involved with the psychedelic drug and music scene in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood.[15]

In the late 1960s he worked as a social worker for the city of San Francisco welfare department. He helped organize a social worker's union, the SSEU, and was elected vice president in 1968, and president in 1969.[16] The local Situationist group Contradiction denounced him as a "leftist bureaucrat".[17]

In 1974, Black and Red Press published Unions Against Revolution by Spanish ultra-left theorist Grandizo Munis that included an essay by Zerzan which previously appeared in the journal Telos. Over the next 20 years, Zerzan became intimately involved with the Fifth Estate, Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed, Demolition Derby and other anarchist periodicals. He began to question civilization in the early 80's, after having sought to confront issues around the neutrality of technology and division of labour, at the time when Fredy Perlman was making similar conclusions.[18] He saw civilization itself as the root of the problems of the world and that a hunter-gatherer form of society presented the most egalitarian model for human relations with themselves and the natural world.

Zerzan and the "Unabomber"

In the mid-1990s, Zerzan became a confidant to Theodore Kaczynski, the "Unabomber", after he read Industrial Society and Its Future, the so-called Unabomber Manifesto. Zerzan sat through the Unabomber trial and often conversed with Kaczynski during the proceedings. After Zerzan became known as a friend of the Unabomber, the mainstream media became interested in Zerzan and his ideas.

On May 7, 1995, a full-page interview with Zerzan was featured in The New York Times.[19] In Zerzan's essay "Whose Unabomber?" (1995), he signaled his support for the Kaczynski doctrine, but criticised the bombings:

[T]he mailing of explosive devices intended for the agents who are engineering the present catastrophe is too random. Children, mail carriers, and others could easily be killed. Even if one granted the legitimacy of striking at the high-tech horror show by terrorizing its indispensable architects, collateral harm is not justifiable ...[20]

However, Zerzan in the same essay offered a qualified defense of the Unabomber's actions:

The concept of justice should not be overlooked in considering the Unabomber phenomenon. In fact, except for his targets, when have the many little Eichmanns who are preparing the Brave New World ever been called to account?... Is it unethical to try to stop those whose contributions are bringing an unprecedented assault on life?[20]

Two years later, in the 1997 essay "He Means It — Do You?," Zerzan wrote:

Enter the Unabomber and a new line is being drawn. This time the bohemian schiz-fluxers, Green yuppies, hobbyist anarcho-journalists, condescending organizers of the poor, hip nihilo-aesthetes and all the other "anarchists" who thought their pretentious pastimes would go on unchallenged indefinitely — well, it's time to pick which side you're on. It may be that here also is a Rubicon from which there will be no turning back.

In a 2001 interview with The Guardian, he said:

Will there be other Kaczynskis? I hope not. I think that activity came out of isolation and desperation, and I hope that isn't going to be something that people feel they have to take up because they have no other way to express their opposition to the brave new world.[15]

In a 2014 interview Zerzan stated that he and Kaczynski were "not on terms anymore." He criticized his former friend's 2008 essay "The Truth About Primitive Life: A Critique of Anarchoprimitivism" and expressed disapproval of Individuals Tending Towards the Wild, a Mexican group influenced by the Unabomber's bombing campaign.[21]

Zerzan and the Eugene Anarchist Scene

Zerzan was associated with the Eugene, Oregon anarchist scene.[22]

Criticism: history, catastrophe and anarchism

In his essay "Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm", Murray Bookchin directed criticism from an anarchist point of view at Zerzan's anti-civilizational and anti-technological perspective. He argued that Zerzan's representation of hunter-gatherers was flawed, selective and often patronisingly racist, that his analysis was superficial, and that his practical proposals were nonsensical.

Aside from Murray Bookchin, several other anarchist critiques of Zerzan's primitivist philosophies exist. The pamphlet, "Anarchism vs. Primitivism" by Brian Oliver Sheppard criticizes many aspects of the primitivist philosophy.[23] It specifically rejects the claim that primitivism is a form of anarchism.

Some authors, such as Andrew Flood, have argued that destroying civilization would lead to the death of a significant majority of the population, mainly in poor countries.[24] John Zerzan responded to such claims by suggesting a gradual decrease in population size, with the possibility of people having the need to seek means of sustainability more close to nature.[25]

Flood suggests this contradicts Zerzan's claims elsewhere, and adds that, since it is certain that most people will strongly reject Zerzan's supposed utopia, it can only be implemented by authoritarian means, against the will of billions.[24]

In his essay "Listen Anarchist!", Chaz Bufe criticized the primitivist position from an anarchist perspective, pointing out that primitivists are extremely vague about exactly which technologies they advocate keeping and which they seek to abolish, noting that smallpox had been eradicated thanks to medical technology.[26]

Theodore J. Kaczynski, better known as the Unabomber, is a surprisingly harsh critic of the current Anarcho-Primitivist mainstream and Zerzan in particular for what he sees as a foolish and invalid projection of leftist values such as gender equality, pacifism and leisure time onto the primitive way of life. Kaczynski holds that the values of gender equality, pacifism, leisure time, etc., while still admirable, are exactly the values of techno-industrial civilization and its promised techno-utopia. Second, he holds that having such an interpretation is counter-productive to the ultimate anti-civilization/anti-tech goal as it attracts "leftist types" who are by nature uncommitted and act to dilute the movement. Kaczynski insists that the core values of freedom, autonomy, dignity, and human fulfillment must be emphasized above all others.[27]

Selected works

Books and pamphlets

- Time and Time Again. Detritus Books, 2018.

- Why hope? The Stand Against Civilization. Feral House, 2015.

- Future Primitive Revisited. Feral House, May 2012.

- Origins of the 1%: The Bronze Age pamphlet. Left Bank Books, 2012.

- Origins: A John Zerzan Reader. Joint publication of FC Press and Black and Green Press, 2010.

- Twilight of the Machines. Feral House, 2008.

- Running On Emptiness. Feral House, 2002.

- Against Civilization (editor). Uncivilized Books, 1999; Expanded edition, Feral House, 2005.

- Future Primitive. Autonomedia, 1994.

- Questioning Technology (co-edited with Alice Carnes). Freedom Press, 1988; 2d edition, New Society, 1991, ISBN 978-0-900384-44-8

- Elements of Refusal. Left Bank Books, 1988; 2d edition, C.A.L. Press, 1999.

Articles

- Telos 141, Second-Best Life: Real Virtuality. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Winter 2007.

- Telos 137, Breaking the Spell: A Civilization Critique Perspective. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Winter 2006.

- Telos 124, Why Primitivism?. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Summer 2002.

- Telos 60, Taylorism and Unionism: The Origins of a Partnership. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Summer 1984.

- Telos 50, Anti-Work and the Struggle for Control. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Winter 1981–1982.

- Telos 49, Origins and Meaning of World War I. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Fall 1981.

- Telos 28, Unionism and the Labor Front. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Summer 1978.

- Telos 27, Unionization in America. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Spring 1976.

- Telos 21, Organized Labor versus The Revolt Against Work: The Critical Contest. New York: Telos Press Ltd., Fall 1974.

See also

- Neotribalism

- Species Traitor, publication where John Zerzan regularly contributes

- Surplus, a Swedish movie (atmo, 2003) which contains an interview with John Zerzan

References

- ^ John Zerzan – The Mass Psychology of Misery Archived March 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c John Zerzan – Why Primitivism? Archived December 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Zerzan The Guardian

- ^ a b c John Zerzan – What is Anarchism? Archived June 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "John Zerzan – Future Primitive". Primitivism.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "John Zerzan – Running on Emptiness: The Failure of Symbolic Thought". Primitivism.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ John Zerzan – Number: Its Origin and Evolution Archived June 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Zerzan – Time and its Discontents Archived June 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Zerzan – Patriarchy, Civilization, and the Origins of Gender Archived February 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Zerzan – Organized Labor versus "The Revolt Against Work" Archived June 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Zerzan – Technology Archived June 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Zerzan – Agriculture Archived August 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Zerzan – Globalization and its Apologists: An Abolitionist Perspective Archived February 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Zerzan – "Hakim Bey," Postmodern Anarchist

- ^ a b "Profile of American anarchist John Zerzan | World news". The Guardian. UK. April 20, 2001. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ History of the union Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Contradiction. "Open Letter to John Zerzan, anti-bureaucrat of the San Francisco Social Services Employees Union". Bopsecrets.org. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Interview: Anarcho-Primitivist Thinker and Activist John Zerzan | CORRUPT.org: Conservation & Conservatism". CORRUPT.org. December 7, 2008. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Prominent Anarchist Finds Unsought Ally in Serial Bomber (New York Times article)

- ^ a b John Zerzan – Whose Unabomber? Archived June 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Anarcho-Primitivist Who Wants Us All To Give Up Technology". Vice Media Inc. USA. June 25, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ "Part. III: Eco-Anarchy Imploding". Eugene Weekly. November 22, 2006. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Anarchism vs. Primitivism by Brian Oliver Sheppard". Libcom.org. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ a b "Civilization, Primitivism, Anarchism by Andrew Flood". Anarkismo.net. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ [1] Archived September 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chaz Bufe (1987). "Listen Anarchist!". See Sharp Press.

- ^ Technological Slavery: The collected writings of Theodore J. Kaczynski, pp. 128–189.

Further reading

- Creel Commission – June 2006 conversation with John Zerzan and the UK band

- "Radical rethinking" by Sena Christian. (April 17, 2008)

External links

- 1943 births

- Living people

- 21st-century philosophers

- American anarchists

- Anarchist writers

- American anti–Vietnam War activists

- Indigenous rights activists

- Anarchist theorists

- Writers from Salem, Oregon

- Writers from Eugene, Oregon

- American people of Czech descent

- University of Southern California alumni

- Philosophers of technology

- Philosophers of art

- Neo-Luddites

- Anarcho-primitivists

- Green anarchists

- Post-left anarchists

- Anti-consumerists

- Critics of postmodernism

- Critics of work and the work ethic