Anarcho-primitivism

| Part of a series on |

| Green anarchism |

|---|

|

Anarcho-primitivism, also known as anti-civilization anarchism, is an anarchist critique of civilization that advocates a return to non-civilized ways of life through deindustrialization, abolition of the division of labor or specialization, abandonment of large-scale organization and all technology other than prehistoric technology, and the dissolution of agriculture. Anarcho-primitivists critique the origins and alleged progress of the Industrial Revolution and industrial society.[1] Most anarcho-primitivists advocate for a tribal-like way of life while some see an even simpler lifestyle as beneficial. According to anarcho-primitivists, the shift from hunter-gatherer to agricultural subsistence during the Neolithic Revolution gave rise to coercion, social alienation, and social stratification.[2]

Anarcho-primitivism argues that civilization is at the root of societal and environmental problems.[3] Primitivists also consider domestication, technology and language to cause social alienation from "authentic reality". As a result, they propose the abolition of civilization and a return to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.[4]

History

[edit]Roots

[edit]The roots of primitivism lay in Enlightenment philosophy and the critical theory of the Frankfurt School.[5] The early-modern philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau blamed agriculture and cooperation for the development of social inequality and causing habitat destruction.[5] In his Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau depicted the state of nature as a "primitivist utopia";[6] however, he stopped short of advocating a return to it.[7] Instead, he called for political institutions to be recreated anew, in harmony with nature and without the artificiality of modern civilization.[8] Later, critical theorist Max Horkheimer argued that Environmental degradation stemmed directly from social oppression, which had vested all value in labor and consequently caused widespread alienation.[5]

Development

[edit]

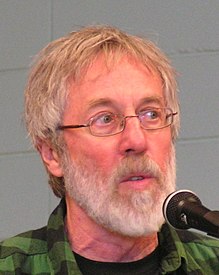

The modern school of anarcho-primitivism was primarily developed by John Zerzan,[9] whose work was released at a time when green anarchist theories of social and deep ecology were beginning to attract interest. Primitivism, as outlined in Zerzan's work, first gained popularity as enthusiasm in deep ecology began to wane.[10]

Zerzan claimed that pre-civilization societies were inherently superior to modern civilization and that the move towards agriculture and the increasing use of technology had resulted in the alienation and oppression of humankind.[11] Zerzan argued that under civilization, humans and other species have undergone domestication, which stripped them of their agency and subjected them to control by capitalism. He also claimed that language, mathematics and art had caused alienation, as they replaced "authentic reality" with an abstracted representation of reality.[12] In order to counteract such issues, Zerzan proposed that humanity return to a state of nature, which he believed would increase social equality and individual autonomy by abolishing private property, organized violence and the division of labour.[13]

Primitivist thinker Paul Shepard also criticized domestication, which he believed had devalued non-human life and reduced human life to their labor and property. Other primitivist authors have drawn different conclusions to Zerzan on the origins of alienation, with John Fillis blaming technology and Richard Heinberg claiming it to be a result of addiction psychology.[4]

Adoption and practice

[edit]Primitivist ideas were taken up by the eco-terrorist Ted Kaczynski, although he has been repeatedly criticised for his violent means by more pacifistic anarcho-primitivists, who instead advocate for non-violent forms of direct action.[14] Primitivist concepts have also taken root within the philosophy of deep ecology, inspiring the direct actions of groups such as Earth First!.[15] Another radical environmentalist group, the Earth Liberation Front (ELF), was directly influenced by anarcho-primitivism and its calls for rewilding.[16]

Primitivists and green anarchists have adopted the concept of ecological rewilding as part of their practice, i.e., using reclaimed skills and methods to work towards a sustainable future while undoing institutions of civilization.[17]

Anarcho-primitivist periodicals include Green Anarchy and Species Traitor. The former, self-described as an "anti-civilization journal of theory and action" and printed in Eugene, Oregon, was first published in 2000 and expanded from a 16-page newsprint tabloid to a 76-page magazine covering monkeywrenching topics such as pipeline sabotage and animal liberation. Species Traitor, edited by Kevin Tucker, is self-described as "an insurrectionary anarcho-primitivist journal", with essays against literacy and for hunter gatherer societies. Adjacent periodicals include the radical environmental journal Earth First![18]

Criticisms

[edit]A common criticism is of hypocrisy, i.e. that people rejecting civilization typically maintain a civilized lifestyle themselves, often while still using the very industrial technology that they oppose in order to spread their message. Activist writer Derrick Jensen counters that this criticism merely resorts to an ad hominem argument, attacking individuals but not the actual validity of their beliefs.[19] He further responds that working to entirely avoid such hypocrisy is ineffective, self-serving, and a convenient misdirection of activist energies.[20] Primitivist John Zerzan admits that living with this hypocrisy is a necessary evil for continuing to contribute to the larger intellectual conversation.[21]

Wolfi Landstreicher and Jason McQuinn, post-leftists, have both criticized the romanticized exaggerations of indigenous societies and the pseudoscientific (and even mystical) appeal to nature they perceive in anarcho-primitivist ideology and deep ecology.[22][23]

Ted Kaczynski also argued that anarcho-primitivists have exaggerated the short working week of primitive society, arguing that they only examine the process of food extraction and not the processing of food, creation of fire and childcare, which adds up to over 40 hours a week.[24]

See also

[edit]- Abecedarians, religious sect supposedly opposed to learning

- Agrarian socialism

- Khmer Rouge

- Anti-modernization

- Back-to-the-land movement

- Deep ecology

- Degrowth

- Deindustrialization

- Doomer

- Earth liberation

- Eco-communalism

- Ecofeminism

- Ecofascism

- Environmental ethics

- Evolutionary psychology

- Freedomites

- Green anarchism

- Green Anarchy

- Hunter-gatherer

- Idea of Progress

- Jacques Camatte

- Neo-Luddism

- Ted Kaczynski, neo-Luddite and domestic terrorist

- Neo-tribalism

- Noble savage

- Post-left anarchy

- Primitive communism

- Rewilding (conservation biology)

- Romanticism

- Solarpunk

- State of nature

- Survivalism

- Year Zero (political notion)

- National Anarchism

- Individualists Tending to the Wild

- Ecoterrorism

Notes

[edit]- ^ el-Ojeili & Taylor 2020, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Jeihouni & Maleki 2016, p. 67.

- ^ Aaltola 2010, p. 164.

- ^ a b Aaltola 2010, p. 166.

- ^ a b c Aaltola 2010, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Long 2013, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Long 2013, pp. 218–219; Marshall 2008, p. 124.

- ^ Long 2013, pp. 218–219; Marshall 2008, p. 15.

- ^ Aaltola 2010, pp. 164–165; Price 2012, pp. 240–241; Price 2019, p. 289.

- ^ Price 2012, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Price 2012, pp. 240–241; Price 2019, p. 289.

- ^ Aaltola 2010, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Aaltola 2010, p. 165.

- ^ Aaltola 2010, p. 167.

- ^ Aaltola 2010, pp. 167–170.

- ^ Humphrey 2013, p. 298.

- ^ Etherington 2024, p. 246.

- ^ Dodge, Chris (July 2006). "Apocalypse Soon?". Utne. pp. 38–39. ISSN 1544-2225. ProQuest 217426998.

- ^ Jensen, Derrick (2006). The Problem of Civilization. Endgame. Vol. 1. New York: Seven Stories Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-58322-730-5.

- ^ Jensen, 2006, pp. 173–174: "[Although it's] vital to make lifestyle choices to mitigate damage caused by being a member of industrial civilization... to assign primary responsibility to oneself, and to focus primarily on making oneself better, is an immense copout, an abrogation of responsibility. With all the world at stake, it is self-indulgent, self-righteous, and self-important. It is also nearly ubiquitous. And it serves the interests of those in power by keeping our focus off them."

- ^ "Anarchy in the USA". The Guardian. London. 20 April 2001.

- ^ McQuinn, Jason. Why I am not a Primitivist.

- ^ "The Network of Domination".

- ^ Kaczynski, Theodore (2008). The Truth About Primitive Life: A Critique of Primitivism.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aaltola, Elisa (2010). "Green Anarchy: Deep Ecology and Primitivism". In Franks, Benjamin; Wilson, Matthew (eds.). Anarchism and Moral Philosophy. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 161–185. doi:10.1057/9780230289680_9. ISBN 978-0-230-28968-0.

- Becker, Michael (2010). Anarcho-Primitivism: The Green Scare in Green Political Theory (Annual Meeting Paper). Western Political Science Association. pp. 1–16.

- Cudworth, Erika (2019). "Farming and Food". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 641–658. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_36. ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2. S2CID 242090793.

- Eddebo, Johan (2017). "Babylon Will Be Found No More: On Affinities Between Christianity and Anarcho-Primitivism". Journal of Religion and Society. 19: 1–17. ISSN 1522-5658.

- el-Ojeili, Chamsy; Taylor, Dylan (2 April 2020). ""The Future in the Past": Anarcho-primitivism and the Critique of Civilization Today". Rethinking Marxism. 32 (2): 168–186. doi:10.1080/08935696.2020.1727256. ISSN 0893-5696. S2CID 219015323.

- Etherington, Ben (June 2024). "Is Rewilding Twenty-First-Century Primitivism?". Comparative Literature. 76 (2): 240–259. doi:10.1215/00104124-11052901. ISSN 0010-4124.

- Gardenier, Matthijs (2016). "The "anti-tech" movement, between anarcho-primitivism and the neo-luddite". Sociétés. 131 (1): 97–106. doi:10.3917/soc.131.0097. ISSN 0765-3697.

- Humphrey, Matthew (2013). "Environmentalism". In Gaus, Gerald F.; D'Agostino, Fred (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Social and Political Philosophy. Routledge. pp. 291–302. ISBN 978-0-415-87456-4. LCCN 2012013795.

- Jeihouni, Mojtaba; Maleki, Nasser (12 December 2016). "Far from the madding civilization: Anarcho-primitivism and revolt against disintegration in Eugene O'Neill's The Hairy Ape". International Journal of English Studies. 16 (2): 61–80. doi:10.6018/ijes/2016/2/238911. hdl:10201/51564. ISSN 1989-6131.

- Long, Roderick T. (2013). "Anarchism". In Gaus, Gerald F.; D'Agostino, Fred (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Social and Political Philosophy. Routledge. pp. 217–230. ISBN 978-0-415-87456-4. LCCN 2012013795.

- Marshall, Peter H. (2008) [1992]. Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1. OCLC 218212571.

- Morris, Brian (2017). "Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy". In Jun, Nathan (ed.). Brill's Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy. Leiden: Brill. pp. 369–400. doi:10.1163/9789004356894_015. ISBN 978-90-04-35689-4.

- Moore, John (1995). "An Archaeology of the Future: Ursula Le Guin and Anarcho-Primitivism". Foundation: 32. ISSN 0306-4964. ProQuest 1312027489.

- Parson, Sean (2018). "Ecocentrism". In Franks, Benjamin; Jun, Nathan; Williams, Leonard (eds.). Anarchism: A Conceptual Approach. Routledge. pp. 219–233. ISBN 978-1-138-92565-6. LCCN 2017044519.

- Price, Andy (2012). "Social Ecology". In Kinna, Ruth (ed.). The Continuum Companion to Anarchism. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 231–249. ISBN 978-1-4411-4270-2.

- Price, Andy (2019). "Green Anarchism". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 281–291. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_16. ISBN 978-3-319-75620-2. S2CID 242090793.

- Purkis, Johnathan (2012). "The Hitchhiker as Theorist: Rethinking Sociology and Anthropology from an Anarchist Perspective". In Kinna, Ruth (ed.). The Continuum Companion to Anarchism. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 140–161. ISBN 978-1-4411-4270-2.

- Shakoor, Abdul; Ahmad, Mustanir (2022). "Anarcho-Primitivism in D.H. Lawrence's Post War Fiction: An Eco-Critical Analysis". Pakistan Journal of Social Research. 4 (4): 10–17. doi:10.52567/pjsr.v4i04.782. ISSN 2710-3137. S2CID 254323210.

- Smith, Mick (2002). "The State of Nature: The Political Philosophy of Primitivism and the Culture of Contamination". Environmental Values. 11 (4): 407–425. doi:10.3197/096327102129341154. ISSN 1752-7015.

Further reading

[edit]- Filiss, John (2002). "What is Primitivism?". Primitivism. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019.

- Sheppard, Brian Oliver (2008) [2003]. Anarchism vs Primitivism. London: Active Distribution. OCLC 1291401071.

- Zerzan, John; Carnes, Alice, eds. (1991). Questioning Technology. New Society Publishers. ISBN 0-86571-205-0.

- Zerzan, John (1994). Future Primitive and Other Essays. Autonomedia. ISBN 1-57027-000-7.

- Zerzan, John (1999) [1988]. Elements of Refusal (Revised ed.). Columbia Alternative Library Press. ISBN 1-890532-01-0.

- Zerzan, John (2001). "Language: Origin and Meaning". Primitivism. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019.

- Zerzan, John (2002). Running on Emptiness: The Pathology of Civilization. Los Angeles: Feral House.

- Zerzan, John, ed. (2005). Against Civilization. Los Angeles: Feral House.

- Zerzan, John (2008). Twilight of the Machines. Los Angeles: Feral House. ISBN 978-1-932595-31-4.

External links

[edit] Media related to Anarcho-primitivism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Anarcho-primitivism at Wikimedia Commons