LGBTQ rights in the European Union

LGBTQ rights in European Union | |

|---|---|

European Union | |

| Status | Never criminalised in EU law. Last state criminalisation repealed in 1998. |

| Military | Allowed to serve openly in all states |

| Discrimination protections | Outlawed in employment with further protections in some member states' law |

| Family rights | |

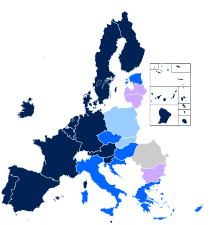

| Recognition of relationships | Same-sex marriage in 13/27 states Recognition of same-sex unions in 23/27 states No recognition of same-sex couples in 4/27 states |

| Restrictions | Same-sex marriage constitutional ban in 7/27 states. |

| Adoption | Joint adoption in 14/27 states Step-child adoption in 18/27 states |

LGBT rights in the European Union are protected under the European Union's (EU) treaties and law. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in all EU states and discrimination in employment has been banned since 2000. However, EU states have different laws when it comes to any greater protection, same-sex civil union, same-sex marriage, adoption by same-sex couples.

Treaty protections

The Treaty on European Union, in its last version as updated by the Treaty of Lisbon in 2007 and in force as of 2009, makes the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union legally binding for the member state of the European Union and the European Union itself. In turn, Article 21 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union includes an anti-discrimination provision that states that "any discrimination based on any ground such as [...] sexual orientation shall be prohibited."[1][2][3]

Furthermore, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union provides in Articles 10 that the European Union has a positive duty to combat discrimination (among other things) on the grounds of sexual orientation and provides in Article 19 ways for the Council and the European Parliament to actively propose pass legislation to do so. These provisions were enacted by the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1999.[1][2]

Legislative protection

Discrimination in employment

Following the inclusion in the Treaties of the above-mentioned provisions, Directive 2000/78/EC "Directive establishing a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation" was enacted in 2000. This framework directive compels all EU states to adopt anti-discrimination legislation in employment. That legislation has to include provisions to protect people from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.[2]

In practice, this protects EU citizens from being refused a job, or from being fired, because of their sexual orientation. It also protects them from being harassed by a colleague due to their sexual orientation.

Discrimination in the provisioning of goods and services

Directive 2000/78/EC does not cover being refused medical services or treatment, refusal of being given a double room in a hotel, protection from bullying in a school and refusal of social security schemes (e.g. survivors' pensions and financial assistance to carers). Protection under EU law in these circumstances exists, but is granted on the grounds of race or gender only.[4]

As such, in 2008, a proposal of a Directive to more broadly fight anti-discrimination has been introduced, which would outlaw discrimination in the areas of social protection, social advantages, education and access to supply of goods, on the basis of religious belief, disability, age, and sexual orientation.[5] However, despite strong support from the European Parliament, the directive has since been stalled in the Council.[6]

Transgender rights

EU law currently takes a different approach to transgender issues. Despite the European Parliament adopting a resolution on transgender rights as early as 1989, transgender identity is not incorporated into any EU funding and was not mentioned in the law establishing the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) as sexual orientation was. However, the case law of the European Court of Justice provides some protection by interpreting discrimination on the basis of 'sex' to also refer to people who have had 'gender reassignment'. Thus all EU sex discrimination law applies to transgender people.[2] In 2002, the 1976 equal treatment directive was revised to include discrimination based on gender identity, to reflect case law on the directive.[7]

Intersex rights

In February 2019, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the rights of intersex people. The resolution called European Union member states to legislate better policies that protected intersex individuals, especially from unnecessary surgery and discrimination. It stated that the parliament "strongly condemns sex-normalizing treatments and surgery; welcomes laws that prohibit such surgery, as in Malta and Portugal, and encourages other member states to adopt similar legislation as soon as possible." The resolution also urged legal gender recognition based on self-determination. It also confirms that intersex people are "exposed to multiple instances of violence and discrimination in the European Union" and calls on the European Commission and the Members States to propose legislation to address these issues. It also includes the need of adequate counselling and support for intersex people and their families, measures to end the stigma and pathologisation intersex people face and increased funding for intersex-led civil society organisations.[8][9][10]

Other actions

Between 2001 and 2006, a Community Action Programme to Combat Discrimination involved the expenditure of €100 million to fight discrimination in a number of areas, including sexual orientation.[7]

In 2009 the European Commission has acted to tone down a law in Lithuania that included homophobic language and also aimed to support the gay pride parade in the country and others under threat of banning.[2]

Foreign relations

In June 2010, the Council of the European Union adopted a non-binding toolkit to promote LGBT people's human rights.[11][12]

In June 2013, the Council upgraded it to binding LGBTI Guidelines instructing EU diplomats around the world to defend the human rights of LGBTI people.[13][14]

Same-sex unions

Same-sex marriage has been legalised in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden. Same-sex civil unions have been legalised in Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Slovenia. In Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Ireland, civil partnerships were legal between 1989 and 2012, and between 1995 and 2009, and between 2002 and 2017, and between 2011 and 2015, respectively. In Germany, registered life partnerships were legal between 2001 and 2017. However, existing civil unions/registered life partnerships are still recognised in all of these countries.

Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia have constitutionally defined marriage as being between a man and a woman. In December 2020, Hungary also explicitly legally banned adoption for same-sex couples within its constitution.[15][16]

European Union law (the Citizens’ Rights Directive 2004/38/EC) requires those member states that legalised same-sex partnerships to recognise each other's partnerships for the purpose of freedom of movement.[17] The European Parliament has however approved a report calling for mutual recognition.[18][19]

According to European Court of Justice case law based on the Employment Equality Framework Directive, employees in a civil partnership with a same-sex partner must be granted the same benefits as those granted to their colleagues upon their marriage, where marriage is not possible for same-sex couples. The Court established this principle in 2008 in the case of Tadao Maruko v. Versorgungsanstalt der deutschen Bühnen with regards to a German registered life partnership. In December 2013, the Court confirmed this in the case of Frédéric Hay v. Crédit agricole mutuel (C-267/12) with regards to a French civil solidarity pact, which is significantly inferior to marriage than a German registered life partnership.[20][21]

Also, according to the European Court of Justice in the case of Coman and Others, by judgement of 5 June 2018, a "spouse" (or partner or any other family member) in the Free Movement Directive (2004/38/EC) includes a (foreign) same-sex spouse; member states are required to confer the right of residence on the (foreign) same-sex spouse of a citizen of the European Union.[22][23] However, most of east-central European new EU member countries (A8 countries) do not recognise same-sex unions themselves, Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania, but are still bound by a ruling by the European Court of Justice to recognise same-sex marriages performed within the EU and including an EU citizen for the purposes of granting legal residence,[24] though they do not always respect this ruling in practice (in case of Romania is still ignoring implementation of the ruling).[25]

Family rights

In 2021, 10 EU member states refused to recognize same-sex couples as joint parents to their children. This leads to situations where two people recognized as parents in one country would have their family ties legally dissolve after crossing a border. A frequently encountered issue is that birth certificates issued in one member state and listing two people of the same sex as parents are not recognized in other countries. Some children do not have passports as a result.[26] The pending CJEU case V.M.A. v. Stolichna Obsthina involves a child who could not claim Bulgarian nationality because her parents were a lesbian couple.[27] A policy brief commissioned by European Parliament Committee on Petitions recommends that the European Commission or the CJEU should clarify that Directive 2004/38 on free movement also applies to rainbow families, who should not be discriminated against in their exercise of EU free movement rights.[26] The case was finally decided on 14 December 2021, with the CJEU accepting the European Parliament Committee on Petitions's position, and finding Bulgaria in breach of EU law for not issuing documents to the child of the lesbian couple. The decision points out that while it is still a Member State's prerogative to decide whether or not to extend same-sex marriage and LGBT adoption rights to its own citizen, this choice cannot come at the expense of the child being deprived of the relationship of one of her parents while exercising her rights to freedom of movement within the EU.[28][29]

Conversion therapy

In March 2018, a majority of representatives in the European Parliament passed a resolution in a 435–109 vote condemning conversion therapy and urging European Union member states to ban the practice.[30][31][32] A report released by the European Parliament Intergroup on LGBT Rights after the measure was passed stated that "Currently, only Malta and some regions in Spain have explicitly banned LGBTI conversion therapies."[33] In 2020, conversion therapy for minors was also banned in Germany by law.[34]

Member State laws on sexual orientation

Openly gay people are allowed to serve in the military of every EU country since 2018.

In December 2016, Malta became the first country in the EU – as well as in Europe – to ban conversion therapy.[35][36][37]

| LGBT rights in: | Unregistered cohabitation | Civil union | Marriage | Adoption | Anti-discrimination laws | Hate crime/speech laws |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (Since 2003)[38] | Yes (Registered Partnership since 2010)[39] | Yes (Since 2019[40])[41][42] | Yes (Since 2016)[43] | All[44] | Yes[44] | |

| No | Yes (Legal Cohabitation since 2000)[45] | Yes (Since 2003)[46] | Yes (Since 2006)[47] | All[44] | Yes | |

| No | No | Constitutional ban since 1991[48] | No | All[44] | No | |

| Yes (Since 2003)[49][50] | Yes (Life Partnership since 2014)[50] | Constitutional ban since 2013[51] | Yes (Since 2021)[52] | All[44] | Yes | |

| No | Yes (Civil Cohabitation since 2015) [53] | No | No | All[54] | Yes[55] | |

| Yes (Since 2001)[56] | Yes (Registered Partnership since 2006)[57] | No (pending) | No (Step-child adoption pending. It is possible for a person in a registered partnership to adopt as an individual)[58] | All | No | |

| Yes (Since 1986) [59] |

Registered Partnership from 1989 to 2012; certain partnerships are still recognised | Yes (Since 2012)[60] | Yes (Since 2010)[61] | All[44] | Yes | |

| No | Yes (Cohabitation Agreement since 2016)[62] | Recognition of marriage celebrated abroad since 2016[63] | Step-child adoption since 2016 | All[44] | Yes[44] | |

| No | Registered Partnership from 1989 to 2012; certain partnerships are still recognised[64] | Yes (Since 2017)[65] | Yes (Since 2017) | All[44] | Yes[44] | |

| Yes (Since 1999)[66] | Yes (Civil Solidarity Pact since 1999)[66] | Yes (Since 2013)[67] | Yes (Since 2013) | All[44] | Yes | |

| No | Registered Partnership from 2001 to 2017; certain partnerships are still recognised[68] | Yes (Since 2017)[69] | Yes (Since 2017)[70][68] | All[44] | Yes[71] | |

| No | Yes (Cohabitation agreement since 2015)[72] | No | Same-sex couples in civil partnerships are allowed to become foster parents. Single individuals, regardless of sexual orientation, may adopt.[73] | All | Yes | |

| Yes (Since 1996)[74][75] | Yes (Registered Partnership since 2009)[76] | Constitutional ban since 2012[77][78] | Constitutional ban since 2020[79] | All[44] | Yes[44] | |

| Yes (Since 2011)[80] | Civil Partnership from 2011 to 2015; certain partnerships are still recognised[80] | Yes (since 2015)[81] | Yes (Since 2015) | All[44] | Yes | |

| Yes (since 2016)[82] | Yes (Civil Union since 2016)[83] | In 2018 the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriages performed abroad must be registered as civil unions[84] | Stepchild adoption admitted by the Court of Cassation since 2016[85] | Some[vague] | No | |

| No | No | Constitutional ban since 2006[86] | No | Some[vague] | No | |

| No | No | Constitutional ban since 1992[87] | No | All[44] | Yes[44] | |

| No | Yes (Registered Partnership since 2004)[88] | Yes (Since 2015)[89] | Yes (Since 2015) | All[90] | Yes[91] | |

| Yes (Since 2017)[92] | Yes (Civil Union since 2014)[93] | Yes (Since 2017)[94] | Yes (Since 2014)[93] | All[95] | Yes[44] | |

| Yes (Since 1979)[96] | Yes (Registered Partnership since 1998)[97] | Yes (Since 2001)[98] | Yes | All[44] | Yes | |

| Yes (Since 2012) | No | Constitutional ban since 1997[99][100][101][102][103][104] | No | Some[vague] | No | |

| Yes (Since 2001)[105] | Yes | Yes (Since 2010)[106] | Yes (Since 2016) | All[44] | Yes | |

| No | No | No | No | All[44] | Yes | |

| Yes (Limited rights for "close person" recognized under civil and penal law since 2018)[107][108] | No | Constitutional ban since 2014[109] | No | All[44] | Yes[110] | |

| Yes (Since 2006)[111] | Yes (Registered Partnership since 2017)[112] | No | Step-child adoption since 2011 | All[44] | Yes[44] | |

| Yes (Since 1995)[113][114] | Yes (All regions and autonomous cities of Spain since 2018) | Yes (Since 2005)[115] | Yes | All[44] | Yes | |

| Yes (Since 1988)[116][117][118] | Registered Partnership from 1995 to 2009; certain partnerships are still recognised[119] | Yes (Since 2009)[120] | Yes (Since 2002)[121] | All[44] | Yes |

Due to the Cyprus dispute placing Northern Cyprus outside the Republic of Cyprus' control, EU law is suspended in the area governed by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

| LGBT rights in: | Civil union | Marriage | Adoption | Anti-discrimination laws | Hate crime/speech laws |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | No | No | All | Yes |

Public opinion

Below is the share of respondents per country who agreed with the following statements in the 2019 Eurobarometer on Discrimination.[122]

| Member state | "Gay, lesbian and bisexual people should have the same rights as heterosexual people" |

"There is nothing wrong in a sexual relationship between two persons of the same sex" |

"Same sex marriages should be allowed throughout Europe" |

Change from 2015 on last statement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 76% | 72% | 69% | +8 | |

| 70% | 66% | 66% | +4 | |

| 84% | 82% | 82% | +5 | |

| 39% | 20% | 16% | -1 | |

| 44% | 36% | 39% | +2 | |

| 63% | 40% | 36% | -1 | |

| 57% | 57% | 48% | -9 | |

| 89% | 90% | 89% | +2 | |

| 53% | 49% | 41% | +10 | |

| 80% | 79% | 76% | +10 | |

| 85% | 85% | 79% | +8 | |

| 88% | 86% | 84% | +18 | |

| 64% | 44% | 39% | +6 | |

| 48% | 41% | 33% | -6 | |

| 83% | 80% | 79% | -1 | |

| 68% | 59% | 58% | +3 | |

| 49% | 25% | 24% | +5 | |

| 53% | 35% | 30% | +6 | |

| 87% | 88% | 85% | +10 | |

| 73% | 73% | 67% | +2 | |

| 97% | 92% | 92% | +1 | |

| 49% | 49% | 45% | +17 | |

| 78% | 69% | 74% | +13 | |

| 38% | 29% | 29% | +8 | |

| 31% | 29% | 20% | -4 | |

| 64% | 60% | 62% | +8 | |

| 91% | 89% | 86% | +2 | |

| 98% | 95% | 92% | +2 |

See also

- LGBT rights in Europe

- LGBT adoption in Europe

- Recognition of same-sex unions in Europe

- Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights

- European Union Fundamental Rights Agency

- LGBT ideology-free zone

References

- ^ a b Consolidated versions of the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, European Union 2009

- ^ a b c d e Perspective: what has the EU done for LGBT rights? Archived 21 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Café Babel 17 May 2010

- ^ CHARTER OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, European Union 2000

- ^ "ILGA-Europe". Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Why ILGA-Europe supports the proposed Anti-Discrimination Directive Archived 5 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, ILGA-Europe

- ^ European Parliament renews call for anti-discrimination laws for LGBT people, LGBTQ Nation

- ^ a b "ILGA-Europe". Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "A Milestone for Intersex Rights: The European Parliament adopts landmark resolution on the rights of intersex people". 14 February 2019.

- ^ "MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION on the rights of intersex people". www.europarl.europa.eu.

- ^ "European Parliament passes historic intersex rights resolution". 26 February 2019.

- ^ "MEPs welcome new toolkit to defend LGBT people's human rights". The European Parliament's Intergroup on LGBT Rights. 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Toolkit to Promote and Protect the Enjoyment of all Human Rights by Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) People" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 17 June 2010.

- ^ "EU foreign affairs ministers adopt ground-breaking global LGBTI policy". The European Parliament Intergroup on LGBT Rights. 24 June 2013.

- ^ "Guidelines to promote and protect the enjoyment of all human rights by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) persons" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 24 June 2013.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ "DIRECTIVE 2004/38/EC on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely".

- ^ Report on civil law, commercial law, family law and private international law aspects of the Action Plan Implementing the Stockholm Programme, European Parliament

- ^ EU-Wide Recognition of Member States’ Gay Marriage, Civil Partnership a Step Closer, WGLB

- ^ "Same-sex civil partners cannot be denied employment benefits reserved to marriage". ILGA-Europe. 13 December 2013. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014.

- ^ "PRESS RELEASE No 159/13" (PDF). Court of Justice of the European Union. 12 December 2013.

- ^ "Judgment in Case C-673/16 (Press Release)" (PDF). Court of Justice of the European Union. 5 June 2018.

- ^ "Same-sex spouses have EU residence rights, top court rules". BBC News. 5 June 2018.

- ^ "Same-sex spouses have EU residence rights, top court rules". BBC News. 5 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Boffey, Daniel (14 September 2021). "MEPs condemn failure to respect rights of same-sex partners in EU". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ a b Obstacles to the free movement of rainbow families in the EU, commissioned by European Parliament Committee on Petitions (PETI), published March 2021, authors Alina Tryfonidou and Robert Wintemute

- ^ Isidro, Marta Requejo (20 April 2021). "AG Kokott on C-490/20, V.M.A. v Stolichna Obshtina, Rayon 'Pancharevo'". EAPIL. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Child, being a minor and a Union citizen, whose birth certificate was drawn up by the host Member State and designates as parents two persons of the same sex: the Member State of which the child is a national is obliged to issue an identity card or a passport to that child without requiring a birth certificate to be drawn up beforehand by its national authorities" (PDF). Court of Justice of the European Union. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Zalan, Eszter (15 December 2021). "EU top court: Same-sex parents with children are 'family". Euobserver. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "EU-Parlament stärkt LGBTI-Grundrechte". queer.de.

- ^ "Schwulissimo - Europäisches Parlament verurteilt die "Heilung" von Homosexuellen". schwulissimo.de. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ "European Parliament condemns gay 'cure' therapy and tells EU member states to ban it". 1 March 2018.

- ^ "Malta bans 'gay cure' conversion therapy". BBC News. 6 December 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Germany passes ban on 'gay conversion therapy'". BBC News. 8 May 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Benjamin, Butterworth. "Malta just became the first country in Europe to ban 'gay cure' therapy". Pink News. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016.

- ^ Stack, Liam (7 December 2016). "Malta Outlaws 'Conversion Therapy,' a First in Europe". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ Henley, Jon (7 December 2016). "Malta becomes first European country to ban 'gay cure' therapy". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016.

- ^ "HUDOC Search Page". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "RIS - Eingetragene Partnerschaft-Gesetz - Bundesrecht konsolidiert, Fassung vom 19.05.2020". www.ris.bka.gv.at.

- ^ "Der Österreichische Verfassungsgerichtshof - Same-sex marriage". www.vfgh.gv.at. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "49/A (XXV. GP) - Allgemeines bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, Änderung". www.parlament.gv.at.

- ^ "498/A (XXV. GP) - Allgemeines bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, Änderung". www.parlament.gv.at.

- ^ "Österreich hebt Adoptionsverbot für Homo-Paare auf". queer.de. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "Rainbow Europe 2017". ILGA-Europe. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ "Gesetz zur Einführung des gesetzlichen Zusammenwohnens" (PDF).

- ^ "LOI - WET". www.ejustice.just.fgov.be.

- ^ "LOI - WET". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "National Assembly of the Republic of Bulgaria - Constitution". National Assembly of the Republic of Bulgaria. 6 February 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

Matrimony shall be a free union between a man and a woman.

- ^ "Zakon o istospolnim zajednicama". narodne-novine.nn.hr.

- ^ a b "Zakon o životnom partnerstvu osoba istog spola - Zakon.hr". www.zakon.hr.

- ^ "Ustav Republike Hrvatske" (PDF) (in Croatian). Ustavni sud Republike Hrvatske. 15 January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Enis Zebić (6 May 2021). "Poslije odluke suda Hrvatska čeka prve istospolne usvojitelje" [After the court's decision Croatia awaits its first same-sex adoptive parents]. Radio Slobodna Evropa. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Cyprus: Penal code amended to protect against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity". PinkNews. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ "House votes to criminalise homophobia". Cyprus Mail. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "glbtq >> social sciences >> Prague". Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Portál veřejné správy". portal.gov.cz.

- ^ "Sněmovní tisk 320 Novela z. o registrovaném partnerství" (in Czech). Parlament České republiky. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "1985-86, 1. samling - L 138 (oversigt): Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om afgift af arv og gave. (Lempelse af arveafgiften for samlevende søskende og samlevende personer af samme køn)" (in Danish). webarkiv.ft.dk. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Retsinformation". www.retsinformation.dk.

- ^ "L 146 Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om registreret partnerskab, lov om en børnefamilieydelse og lov om børnetilskud og forskudsvis udbetaling af børnebidrag" (in Danish). Folketinget. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Riigikogu". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Gay couple win right to be married in Estonia". 30 January 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ (in Swedish) Lag om registrerat partnerskap

- ^ "Lag om ändring av äktenskapslagen".

- ^ a b "Loi n° 99-944 du 15 novembre 1999 relative au pacte civil de solidarité | Legifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr.

- ^ "LOI n° 2013-404 du 17 mai 2013 ouvrant le mariage aux couples de personnes de même sexe | Legifrance".

- ^ a b "LPartG - nichtamtliches Inhaltsverzeichnis". www.gesetze-im-internet.de.

- ^ "§ 1353 Eheliche Lebensgemeinschaft" (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ "§ 1741 Zulässigkeit der Annahme" (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Strafgesetzbuch: Volksverhetzung

- ^ "Greece legalizes same-sex civil partnerships". 23 December 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "- The Washington Post". Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ "1996. évi XLII. törvény a Magyar Köztársaság Polgári Törvénykönyvéről szóló 1959. évi IV. törvény módosításáról". Archived from the original on 3 July 2015.

- ^ "ILGA Euroletter 42". Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Kft, Wolters Kluwer Hungary. "2009. évi XXIX. törvény a bejegyzett élettársi kapcsolatról, az ezzel összefüggő, valamint az élettársi viszony igazolásának megkönnyítéséhez szükséges egyes törvények módosításáról - Hatályos Jogszabályok Gyűjteménye". net.jogtar.hu.

- ^ "T/5423 Magyarország Alaptörvényének 6. módosítása".

- ^ "T/5424 Az azonos neműek házasságkötéséhez szükséges jogi feltételek megteremtéséről".

- ^ [3]

- ^ a b "Civil Partnership and Certain Rights and Obligations of Cohabitants Act 2010". Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Marriage Act 2015". 15 September 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "XVII Legislatura - XVII Legislatura - Documenti - Temi dell'Attività parlamentare". www.camera.it. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Unioni civili, approvazione definitiva". Camera dei Deputati.

- ^ "Same-sex marriages performed abroad won't be recognized in Italy". www.thelocal.it. 15 May 2018.

- ^ "Cassazione, sì alla stepchild adoption in casi particolari". 22 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA".

- ^ "Loi du 9 juillet 2004 relative aux effets légaux de certains partenariats. - Legilux". eli.legilux.public.lu.

- ^ "Chambre des Députés du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Mémorial A n° 207 de 2006" (PDF).

- ^ "Legislationline". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Cohabitation Act, 2017". Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ a b "ACT No. IX of 2014". Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Marriage Act and other laws Amendment Act 2017". Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "AN ACT to amend the Constitution of Malta". Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Major legal consequences of marriage, cohabitation and registered partnership for different-sex and same-sex partners in the Netherlands" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ^ "wetten.nl - Regeling - Aanpassingswet geregistreerd partnerschap - BWBR0009190". wetten.overheid.nl. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Koninkrijksrelaties, Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en. "Wet openstelling huwelijk". wetten.overheid.nl.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Republic of Poland". Sejm RP. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

Marriage, being a union of a man and a woman, as well as the family, motherhood and parenthood, shall be placed under the protection and care of the Republic of Poland.

- ^ Judgment of the Supreme Court of 7 July 2004, II KK 176/04,

W dotychczasowym orzecznictwie Sądu Najwyższego, wypracowanym i ugruntowanym zarówno w okresie obowiązywania poprzedniego, jak i obecnego Kodeksu postępowania karnego, a także w doktrynie (por. wypowiedzi W. Woltera, A. Zolla, A. Wąska), pojęcie "wspólne pożycie" odnoszone jest wyłącznie do konkubinatu, a w szczególności do związku osób o różnej płci, odpowiadającego od strony faktycznej stosunkowi małżeństwa (którym w myśl art. 18 Konstytucji jest wyłącznie związek osób różnej płci). Tego rodzaju interpretację Sąd Najwyższy, orzekający w niniejszej sprawie, w pełni podziela i nie znajduje podstaw do uznania za przekonywujące tych wypowiedzi pojawiających się w piśmiennictwie, w których podejmowane są próby kwestionowania takiej interpretacji omawianego pojęcia i sprowadzania go wyłącznie do konkubinatu (M. Płachta, K. Łojewski, A.M. Liberkowski). Rozumiejąc bowiem dążenia do rozszerzającej interpretacji pojęcia "wspólne pożycie", użytego w art. 115 § 11 k.k., należy jednak wskazać na całkowity brak w tym względzie dostatecznie precyzyjnych kryteriów.

- ^ "Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 11 May 2005, K 18/04".

Polska Konstytucja określa bowiem małżeństwo jako związek wyłącznie kobiety i mężczyzny. A contrario nie dopuszcza więc związków jednopłciowych. [...] Małżeństwo (jako związek kobiety i mężczyzny) uzyskało w prawie krajowym RP odrębny status konstytucyjny zdeterminowany postanowieniami art. 18 Konstytucji. Zmiana tego statusu byłaby możliwa jedynie przy zachowaniu rygorów trybu zmiany Konstytucji, określonych w art. 235 tego aktu.

- ^ "Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 9 November 2010, SK 10/08".

W doktrynie prawa konstytucyjnego wskazuje się nadto, że jedyny element normatywny, dający się odkodować z art. 18 Konstytucji, to ustalenie zasady heteroseksualności małżeństwa.

- ^ "Judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court of Poland of 25 October 2016, II GSK 866/15".

Ustawa o świadczeniach zdrowotnych finansowanych ze środków publicznych nie wyjaśnia, co prawda, kto jest małżonkiem. Pojęcie to zostało jednak dostatecznie i jasno określone we wspomnianym art. 18 Konstytucji RP, w którym jest mowa o małżeństwie jako o związku kobiety i mężczyzny. W piśmiennictwie podkreśla się, że art. 18 Konstytucji ustala zasadę heteroseksualności małżeństwa, będącą nie tyle zasadą ustroju, co normą prawną, która zakazuje ustawodawcy zwykłemu nadawania charakteru małżeństwa związkom pomiędzy osobami jednej płci (vide: L. Garlicki Komentarz do art. 18 Konstytucji, s. 2-3 [w:] Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Komentarz, Wydawnictwo Sejmowe, Warszawa 2003). Jest wobec tego oczywiste, że małżeństwem w świetle Konstytucji i co za tym idzie - w świetle polskiego prawa, może być i jest wyłącznie związek heteroseksualny, a więc w związku małżeńskim małżonkami nie mogą być osoby tej samej płci.

- ^ "Judgment of the Supreme Administrative Court of Poland of 28 February 2018, II OSK 1112/16".

art. 18 Konstytucji RP, który definiuje małżeństwo jako związek kobiety i mężczyzny, a tym samym wynika z niego zasada nakazująca jako małżeństwo traktować w Polsce jedynie związek heteroseksualny.

- ^ "Lei n. 7/2001 de 11 de Maio" (PDF).

- ^ "Lei n.º 9/2010 de 31 de Maio" (PDF).

- ^ "40/1964 Zb. - Občiansky zákonník". Slov-lex.

- ^ "301/2005 Z.z. - Trestný poriadok". Slov-lex.

- ^ Radoslav, Tomek (4 June 2014). "Slovak Lawmakers Approve Constitutional Ban on Same-Sex Marriage". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "ILGA-Europe". Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Uradni list - Vsebina Uradnega lista". www.uradni-list.si.

- ^ "Uradni list - Vsebina Uradnega lista". www.uradni-list.si.

- ^ "Irish Human Rights & Equality Commission". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Noticias Jurídicas". Noticias Jurídicas.

- ^ "BOE.es - Documento BOE-A-2005-11364". www.boe.es.

- ^ "Lag (1987:813) om homosexuella sambor Svensk författningssamling 1987:1987:813 t.o.m. SFS 2002:1114 - Riksdagen". www.riksdagen.se.

- ^ "Regeringskansliets rättsdatabaser". rkrattsbaser.gov.se.

- ^ "Sambolag (2003:376) Svensk författningssamling 2003:2003:376 t.o.m. SFS 2011:493 - Riksdagen". www.riksdagen.se.

- ^ "Lag (2009:260) om upphävande av lagen (1994:1117) om registrerat partnerskap - Lagen.nu". lagen.nu. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Lag (2009:253) om ändring i äktenskapsbalken" (PDF).

- ^ "Sweden legalises gay adoption". BBC News. 6 June 2002. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/ResultDoc/download/DocumentKy/87771