Howard Zinn

Howard Zinn | |

|---|---|

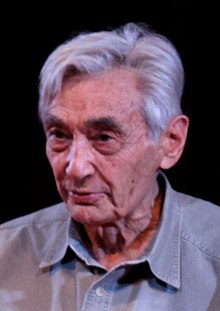

Zinn in 2009 | |

| Born | August 24, 1922 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | January 27, 2010 (aged 87) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Education | New York University (BA) Columbia University (MA, PhD) |

| Occupation(s) | Historian, educator, author, playwright |

| Spouse |

Roslyn Shechter

(m. 1944; died 2008) |

| Children | 2, including Jeff |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | U.S. Army Air Forces |

| Years of service | 1941–1945 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Academic background | |

| Thesis | Fiorello LaGuardia in Congress (1958) |

| Academic work | |

| Institutions | Spelman College Boston University |

| Main interests | Civil rights, war and peace |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

|

Howard Zinn (August 24, 1922 – January 27, 2010)[1] was an American historian, playwright, philosopher, socialist intellectual and World War II veteran. He was chair of the history and social sciences department at Spelman College,[2] and a political science professor at Boston University. Zinn wrote more than 20 books, including his best-selling and influential A People's History of the United States in 1980. In 2007, he published a version of it for younger readers, A Young People's History of the United States.[3]

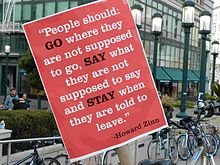

Zinn described himself as "something of an anarchist, something of a socialist. Maybe a democratic socialist."[4][5] He wrote extensively about the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement and labor history of the United States. His memoir, You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train (Beacon Press, 1994), was also the title of a 2004 documentary about Zinn's life and work. Zinn died of a heart attack in 2010, at the age of 87.[6]

Early life

[edit]Zinn was born to a Jewish immigrant family in Brooklyn, New York City, on August 24, 1922. His father, Eddie Zinn, born in Austria-Hungary, immigrated to the US with his brother Samuel before the outbreak of World War I. His mother, Jenny (Rabinowitz) Zinn,[7] emigrated from the Eastern Siberian city of Irkutsk. His parents first became acquainted as workers at the same factory.[8] During the Great Depression, his father worked as a ditch digger and window cleaner, and for a brief time, his parents ran a neighborhood candy store, barely earning a living. For many years, Zinn's father was in the waiters' union and worked as a waiter for weddings and bar mitzvahs.[8]

Both parents were factory workers with limited education when they met and married, and there were no books or magazines in the series of apartments where they raised their children. Zinn's parents introduced him to literature by sending 10 cents plus a coupon to the New York Post for each of the 20 volumes of Charles Dickens' collected works.[8] As a young man, Zinn made the acquaintance of several young Communists from his Brooklyn neighborhood. They invited him to a political rally being held in Times Square. Despite it being a peaceful rally, mounted police charged the marchers. Zinn was hit and knocked unconscious. This would have a profound effect on his political and social outlook.[8]

Howard Zinn studied creative writing at Thomas Jefferson High School in a special program established by principal and poet Elias Lieberman.[9]

Zinn initially opposed entry into World War II, influenced by his friends, by the results of the Nye Committee, and by his ongoing reading. However, these feelings shifted as he learned more about fascism and its rise in Europe. The book Sawdust Caesar had a particularly large impact through its depiction of Mussolini. After graduating from high school in 1940, Zinn took the Civil Service exam and became an apprentice shipfitter in the New York Navy Yard at the age of 18.[10]

Concerns about low wages and hazardous working conditions compelled Zinn and several other apprentices to form the Apprentice Association. At the time, apprentices were excluded from trade unions and thus had little bargaining power, to which the Apprentice Association was their answer.[8] The head organizers of the association, which included Zinn himself, would meet once a week outside of work to discuss strategy and read books that at the time were considered radical. Zinn was the Activities Director for the group. His time in this group would tremendously influence his political views and created for him an appreciation for unions.[11]

World War II

[edit]Eager to fight fascism, Zinn joined the United States Army Air Corps during World War II and became an officer. He was assigned as a bombardier in the 490th Bombardment Group,[12] bombing targets in Berlin, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary.[13] As bombardier, Zinn dropped napalm bombs in April 1945 on Royan, a seaside resort in western France.[14] The anti-war stance Zinn developed later was informed, in part, by his experiences.[15]

On a post-doctoral research mission nine years later, Zinn visited the resort near Bordeaux where he interviewed residents, reviewed municipal documents, and read wartime newspaper clippings at the local library. In 1966, Zinn returned to Royan after which he gave his fullest account of that research in his book, The Politics of History. On the ground, Zinn learned that the aerial bombing attacks in which he participated had killed more than a thousand French civilians as well as some German soldiers hiding near Royan to await the war's end, events that are described "in all accounts" he found as "une tragique erreur" that leveled a small but ancient city and "its population that was, at least officially, friend, not foe." In The Politics of History, Zinn described how the bombing was ordered—three weeks before the war in Europe ended—by military officials who were, in part, motivated more by the desire for their own career advancement than in legitimate military objectives. He quotes the official history of the US Army Air Forces' brief reference to the Eighth Air Force attack on Royan and also, in the same chapter, to the bombing of Plzeň in what was then Czechoslovakia. The official history stated that the Skoda works in Pilsen "received 500 well-placed tons", and that "because of a warning sent out ahead of time the workers were able to escape, except for five persons. "The Americans received a rapturous welcome when they liberated the city.[16]

Zinn wrote:

I recalled flying on that mission, too, as deputy lead bombardier, and that we did not aim specifically at the 'Skoda works' (which I would have noted, because it was the one target in Czechoslovakia I had read about) but dropped our bombs, without much precision, on the city of Pilsen. Two Czech citizens who lived in Pilsen at the time told me, recently, that several hundred people were killed in that raid (that is, Czechs)—not five.[17]

Zinn said his experience as a wartime bombardier, combined with his research into the reasons for, and effects of the bombing of Royan and Pilsen, sensitized him to the ethical dilemmas faced by GIs during wartime.[18] Zinn questioned the justifications for military operations that inflicted massive civilian casualties during the Allied bombing of cities such as Dresden, Royan, Tokyo, and Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II, Hanoi during the War in Vietnam, and Baghdad during the war in Iraq and the civilian casualties during bombings in Afghanistan during the war there. In his pamphlet, Hiroshima: Breaking the Silence[19] written in 1995, he laid out the case against targeting civilians with aerial bombing.

Six years later, he wrote:

Recall that in the midst of the Gulf War, the US military bombed an air raid shelter, killing 400 to 500 men, women, and children who were huddled to escape bombs. The claim was that it was a military target, housing a communications center, but reporters going through the ruins immediately afterward said there was no sign of anything like that. I suggest that the history of bombing—and no one has bombed more than this nation—is a history of endless atrocities, all calmly explained by deceptive and deadly language like "accident", "military target", and "collateral damage".[20]

Education

[edit]After World War II, Zinn attended New York University on the GI Bill, graduating with a BA in 1951. At Columbia University, he earned an MA (1952) and a PhD in history with a minor in political science (1958). His master's thesis examined the Colorado coal strikes of 1914.[9] His doctoral dissertation Fiorello LaGuardia in Congress was a study of Fiorello La Guardia's congressional career, and it depicted "the conscience of the twenties" as LaGuardia fought for public power, the right to strike, and the redistribution of wealth by taxation. "His specific legislative program," Zinn wrote, "was an astonishingly accurate preview of the New Deal." It was published by the Cornell University Press for the American Historical Association. Fiorello LaGuardia in Congress was nominated for the American Historical Association's Beveridge Prize as the best English-language book on American history.[21]

His professors at Columbia included Harry Carman, Henry Steele Commager, and David Donald.[9] But it was Columbia historian Richard Hofstadter's The American Political Tradition that made the most lasting impression. Zinn regularly included it in his lists of recommended readings, and, after Barack Obama was elected President of the United States, Zinn wrote, "If Richard Hofstadter were adding to his book The American Political Tradition, in which he found both 'conservative' and 'liberal' Presidents, both Democrats and Republicans, maintaining for dear life the two critical characteristics of the American system, nationalism and capitalism, Obama would fit the pattern."[22]

In 1960–61, Zinn was a post-doctoral fellow in East Asian Studies at Harvard University.

Career

[edit]Academic career

[edit]"We were not born critical of existing society. There was a moment in our lives (or a month, or a year) when certain facts appeared before us, startled us, and then caused us to question beliefs that were strongly fixed in our consciousness – embedded there by years of family prejudices, orthodox schooling, imbibing of newspapers, radio, and television. This would seem to lead to a simple conclusion: that we all have an enormous responsibility to bring to the attention of others information they do not have, which has the potential of causing them to rethink long-held ideas."[23]

— Howard Zinn, 2005

Zinn was professor of history at Spelman College in Atlanta from 1956 to 1963, and visiting professor at both the University of Paris and University of Bologna. At the end of the academic year in 1963, Zinn was fired from Spelman for insubordination.[24] His dismissal came from Albert Manley, the first African-American president of that college, who felt Zinn was radicalizing Spelman students.[25]

In 1964, he accepted a position at Boston University (BU), after writing two books and participating in the Civil Rights Movement in the South. His classes in civil liberties were among the most popular at the university with as many as 400 students subscribing each semester to the non-required class. A professor of political science, he taught at BU for 24 years and retired in 1988 at age 66.

"He had a deep sense of fairness and justice for the underdog. But he always kept his sense of humor. He was a happy warrior," said Caryl Rivers, journalism professor at BU. Rivers and Zinn were among a group of faculty members who in 1979 defended the right of the school's clerical workers to strike and were threatened with dismissal after refusing to cross a picket line.[26]

Zinn came to believe that the point of view expressed in traditional history books was often limited. Biographer Martin Duberman noted that when he was asked directly if he was a Marxist, Zinn replied, "Yes, I'm something of a Marxist." He especially was influenced by the liberating vision of the young Marx in overcoming alienation, and disliked what he perceived to be Marx's later dogmatism. In later life he moved more toward anarchism.[27]

He wrote a history text, A People's History of the United States, to provide other perspectives on American history. The book depicts the struggles of Native Americans against European and U.S. conquest and expansion, slaves against slavery, unionists and other workers against capitalists, women against patriarchy, and African-Americans for civil rights. The book was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1981.[28]

In the years since the first publication of A People's History in 1980, it has been used as an alternative to standard textbooks in many college history courses, and it is one of the most widely known examples of critical pedagogy. The New York Times Book Review stated in 2006 that the book "routinely sells more than 100,000 copies a year."[29]

In 2004, Zinn published Voices of a People's History of the United States with Anthony Arnove. Voices is a sourcebook of speeches, articles, essays, poetry and song lyrics by the people themselves whose stories are told in A People's History.

In 2008, the Zinn Education Project was launched to support educators using A People's History of the United States as a source for middle and high school history. The project was started when William Holtzman, a former student of Zinn who wanted to bring Zinn's lessons to students around the country, provided the financial backing to allow two other organizations, Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change to coordinate the project. The project hosts a website with hundreds of free downloadable lesson plans to complement A People's History of the United States.[30]

The People Speak, released in 2010, is a documentary movie based on A People's History of the United States and inspired by the lives of ordinary people who fought back against oppressive conditions over the course of the history of the United States. The film, narrated by Zinn, includes performances by Matt Damon, Morgan Freeman, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Eddie Vedder, Viggo Mortensen, Josh Brolin, Danny Glover, Marisa Tomei, Don Cheadle, and Sandra Oh.[31][32][33]

Civil rights movement

[edit]From 1956 through 1963, Zinn chaired the Department of History and Social Sciences at Spelman College. He participated in the Civil Rights Movement and lobbied with historian August Meier[34] "to end the practice of the Southern Historical Association of holding meetings at segregated hotels."[35]

While at Spelman, Zinn served as an adviser to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and wrote about sit-ins and other actions by SNCC for The Nation and Harper's.[36][37] In 1964, Beacon Press published his book SNCC: The New Abolitionists.[38]

In 1964 Zinn, with the SNCC, began developing an educational program so that the 200 volunteer SNCC civil rights workers in the South, many of whom were college dropouts, could continue with their civil rights work and at the same time be involved in an educational system. Up until then many of the volunteers had been dropping out of school so they could continue their work with SNCC. Other volunteers had not spent much time in college. The program had been endorsed by the SNCC in December 1963 and was envisioned by Zinn as having a curriculum that ranged from novels to books about "major currents" in 20th-century world history, such as fascism, communism, and anti-colonial movements. This occurred while Zinn was in Boston.[39]

Zinn also attended an assortment of SNCC meetings in 1964, traveling back and forth from Boston. One of those trips was to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in January 1964 to participate in a SNCC voter registration drive. The local newspaper, the Hattiesburg American, described the SNCC volunteers in town for the voter registration drive as "outside agitators" and told local blacks "to ignore whatever goes on, and interfere in no way..." At a mass meeting held during the visit to Hattiesburg, Zinn and another SNCC representative, Ella Baker, emphasized the risks that went along with their efforts, a subject probably in their minds since a well-known civil rights activist, Medgar Evers, had been murdered getting out of his car in the driveway of his home in Jackson, Mississippi, only six months earlier. Evers had been the state field secretary for the NAACP.[39]

Zinn was also involved in what became known as Freedom Summer in Mississippi in the summer of 1964. Freedom Summer involved bringing 1,000 college students to Mississippi to work for the summer in various roles as civil rights activists. Part of the program involved organizing "Freedom Schools". Zinn's involvement included helping to develop the curriculum for the Freedom Schools. He was also concerned that bringing 1,000 college students to Mississippi to work as civil rights activists could lead to violence and killings. As a consequence, Zinn recommended approaching Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett and President Lyndon Johnson to request protection for the young civil rights volunteers. Protection was not forthcoming. Planning for the summer went forward under the umbrella of the SNCC, the Congress of Racial Equality ("CORE") and the Council of Federated Organizations ("COFO").[40]

On June 20, 1964, just as civil rights activists were beginning to arrive in Mississippi, CORE activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were en route to investigate the burning of Mount Zion Methodist Church in Neshoba County when two carloads of KKK members led by deputy sheriff Cecil Price abducted and murdered them.[40] Two months later, after their bodies were located, Zinn and other representatives of the SNCC attended a memorial service for the three at the ruins of Mount Zion Methodist Church.[41]

Zinn collaborated with historian Staughton Lynd mentoring student activists, among them Alice Walker,[42] who would later write The Color Purple, and Marian Wright Edelman, founder and president of the Children's Defense Fund. Edelman identified Zinn as a major influence in her life and, in the same journal article, tells of his accompanying students to a sit-in at the segregated white section of the Georgia state legislature.[43] Zinn also co-wrote a column in The Boston Globe with fellow activist Eric Mann, "Left Field Stands".[44]

Although Zinn was a tenured professor, he was dismissed in June 1963 after siding with students in the struggle against segregation. As Zinn described[45] in The Nation, though Spelman administrators prided themselves for turning out refined "young ladies", its students were likely to be found on the picket line, or in jail for participating in the greater effort to break down segregation in public places in Atlanta. Zinn's years at Spelman are recounted in his autobiography You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times. His seven years at Spelman College, Zinn said, "are probably the most interesting, exciting, most educational years for me. I learned more from my students than my students learned from me."[46]

While living in Georgia, Zinn wrote that he observed 30 violations of the First and Fourteenth amendments to the United States Constitution in Albany, Georgia, including the rights to freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and equal protection under the law. In an article on the civil rights movement in Albany, Zinn described the people who participated in the Freedom Rides to end segregation, and the reluctance of President John F. Kennedy to enforce the law.[47] Zinn said that the Justice Department under Robert F. Kennedy and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, headed by J. Edgar Hoover, did little or nothing to stop the segregationists from brutalizing civil rights workers.[48]

Zinn wrote about the struggle for civil rights, as both participant and historian.[49] His second book, The Southern Mystique,[50] was published in 1964, the same year as his SNCC: The New Abolitionists in which he describes how the sit-ins against segregation were initiated by students and, in that sense, were independent of the efforts of the older, more established civil rights organizations.

In 2005, forty-one years after he was sacked from Spelman, Zinn returned to the college, where he was given an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters. He delivered the commencement address,[51][52] titled "Against Discouragement", and said that "the lesson of that history is that you must not despair, that if you are right, and you persist, things will change. The government may try to deceive the people, and the newspapers and television may do the same, but the truth has a way of coming out. The truth has a power greater than a hundred lies."[53]

Anti-war efforts

[edit]Vietnam

[edit]Zinn wrote one of the earliest books calling for the U.S. withdrawal from its war in Vietnam. Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal was published by Beacon Press in 1967 based on his articles in Commonweal, The Nation, and Ramparts. In the opinion of Noam Chomsky, The Logic of Withdrawal was Zinn's most important book:

"He was the first person to say—loudly, publicly, very persuasively—that this simply has to stop; we should get out, period, no conditions; we have no right to be there; it's an act of aggression; pull out. It was so surprising at the time that there wasn't even a review of the book. In fact, he asked me if I would review it in Ramparts just so that people would know about the book."[54]

Zinn's diplomatic visit to Hanoi with Reverend Daniel Berrigan, during the Tet Offensive in January 1968, resulted in the return of three American airmen, the first American POWs released by the North Vietnamese since the U.S. bombing of that nation had begun. The event was widely reported in the news media and discussed in a variety of books including Who Spoke Up? American Protest Against the War in Vietnam 1963–1975 by Nancy Zaroulis and Gerald Sullivan.[55] Zinn and the Berrigan brothers, Dan and Philip, remained friends and allies over the years.

Also in January 1968, he signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the war.[56]

In December 1969, radical historians tried unsuccessfully to persuade the American Historical Association to pass an anti-Vietnam War resolution. "A debacle unfolded as Harvard historian (and AHA president in 1968) John Fairbank literally wrestled the microphone from Zinn's hands."[57]

Daniel Ellsberg, a former RAND consultant who had secretly copied The Pentagon Papers, which described the history of the United States' military involvement in Southeast Asia, gave a copy to Howard and Roslyn Zinn.[58] Along with Noam Chomsky, Zinn edited and annotated the copy of The Pentagon Papers that Senator Mike Gravel read into the Congressional Record and that was subsequently published by Beacon Press.

Announced on August 17[59] and published on October 10, 1971, this four-volume, relatively expensive set[59] became the "Senator Gravel Edition", which studies from Cornell University and the Annenberg Center for Communication have labeled as the most complete edition of the Pentagon Papers to be published.[60][61] The "Gravel Edition" was edited and annotated by Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn, and included an additional volume of analytical articles on the origins and progress of the war, also edited by Chomsky and Zinn.[61]

Zinn testified as an expert witness at Ellsberg's criminal trial for theft, conspiracy, and espionage in connection with the publication of the Pentagon Papers by The New York Times. Defense attorneys asked Zinn to explain to the jury the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam from World War II through 1963. Zinn discussed that history for several hours, and later reflected on his time before the jury.

I explained there was nothing in the papers of military significance that could be used to harm the defense of the United States, that the information in them was simply embarrassing to our government because what was revealed, in the government's own interoffice memos, was how it had lied to the American public. ... The secrets disclosed in the Pentagon Papers might embarrass politicians, might hurt the profits of corporations wanting tin, rubber, oil, in far-off places. But this was not the same as hurting the nation, the people.[62]

Most of the jurors later said that they voted for acquittal. However, the federal judge who presided over the case dismissed it on grounds it had been tainted by the Nixon administration's burglary of the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist.

Zinn's testimony on the motivation for government secrecy was confirmed in 1989 by Erwin Griswold, who as U.S. solicitor general during the Nixon administration sued The New York Times in the Pentagon Papers case in 1971 to stop publication.[63] Griswold persuaded three Supreme Court justices to vote to stop The New York Times from continuing to publish the Pentagon Papers, an order known as "prior restraint" that has been held to be illegal under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The papers were simultaneously published in The Washington Post, effectively nullifying the effect of the prior restraint order. In 1989, Griswold admitted there had been no national security damage resulting from publication.[63] In a column in The Washington Post, Griswold wrote: "It quickly becomes apparent to any person who has considerable experience with classified material that there is massive over-classification and that the principal concern of the classifiers is not with national security, but with governmental embarrassment of one sort or another."

Zinn supported the G.I. anti-war movement during the U.S. war in Vietnam. In the 2001 film Unfinished Symphony: Democracy and Dissent, Zinn provides a historical context for the 1971 anti-war march by Vietnam Veterans against the War. The marchers traveled from Bunker Hill near Boston to Lexington, Massachusetts, "which retraced Paul Revere's ride of 1775 and ended in the massive arrest of 410 veterans and civilians by the Lexington police." The film depicts "scenes from the 1971 Winter Soldier hearings,[64] during which former G.I.s testified about "atrocities" they either participated in or said they had witnessed committed by U.S. forces in Vietnam.[65] Zinn also took part in the 1971 May Day protests (with among others Noam Chomsky and Daniel Ellsberg).[66][67]

In later years, Zinn was an adviser to the Disarm Education Fund.[68]

Iraq

[edit]

Zinn opposed the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq and wrote several books about it. In an interview with The Brooklyn Rail he said,

We certainly should not be initiating a war, as it's not a clear and present danger to the United States, or in fact, to anyone around it. If it were, then the states around Iraq would be calling for a war on it. The Arab states around Iraq are opposed to the war, and if anyone's in danger from Iraq, they are. At the same time, the U.S. is violating the U.N. charter by initiating a war on Iraq. Bush made a big deal about the number of resolutions Iraq has violated—and it's true, Iraq has not abided by the resolutions of the Security Council. But it's not the first nation to violate Security Council resolutions. Israel has violated Security Council resolutions every year since 1967. Now, however, the U.S. is violating a fundamental principle of the U.N. Charter, which is that nations can't initiate a war—they can only do so after being attacked. And Iraq has not attacked us.[69]

He asserted that the U.S. would end Gulf War II when resistance within the military increased in the same way resistance within the military contributed to ending the U.S. war in Vietnam. Zinn compared the demand by a growing number of contemporary U.S. military families to end the war in Iraq to parallel demands "in the Confederacy in the Civil War, when the wives of soldiers rioted because their husbands were dying and the plantation owners were profiting from the sale of cotton, refusing to grow grains for civilians to eat."[70]

Zinn believed that U.S. President George W. Bush and followers of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the former leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, who was personally responsible for beheadings and numerous attacks designed to cause civil war in Iraq, should be considered moral equivalents.[71]

Jean-Christophe Agnew, Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University, told the Yale Daily News in May 2007 that Zinn's historical work is "highly influential and widely used".[72] He observed that it is not unusual for prominent professors such as Zinn to weigh in on current events, citing a resolution opposing the war in Iraq that was recently ratified by the American Historical Association.[73] Agnew added: "In these moments of crisis, when the country is split—so historians are split."[74]

Socialism

[edit]Zinn described himself as "something of an anarchist, something of a socialist. Maybe a democratic socialist."[4][5] He suggested looking at socialism in its full historical context as a popular, positive idea that got a bad name from its association with Soviet Communism. In Madison, Wisconsin, in 2009, Zinn said:

Let's talk about socialism. I think it's very important to bring back the idea of socialism into the national discussion to where it was at the turn of the [last] century before the Soviet Union gave it a bad name. Socialism had a good name in this country. Socialism had Eugene Debs. It had Clarence Darrow. It had Mother Jones. It had Emma Goldman. It had several million people reading socialist newspapers around the country. Socialism basically said, hey, let's have a kinder, gentler society. Let's share things. Let's have an economic system that produces things not because they're profitable for some corporation, but produces things that people need. People should not be retreating from the word socialism because you have to go beyond capitalism.[75]

FBI files

[edit]

On July 30, 2010, a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request resulted in the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) releasing a file with 423 pages of information on Howard Zinn's life and activities. During the height of McCarthyism in 1949, the FBI first opened a domestic security investigation on Zinn (FBI File # 100-360217), based on Zinn's activities in what the agency considered to be communist front groups, such as the American Labor Party,[76] and informant reports that Zinn was an active member of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA).[77] Zinn denied ever being a member and said that he had participated in the activities of various organizations which might be considered Communist fronts, but that his participation was motivated by his belief that in this country people had the right to believe, think, and act according to their own ideals.[77] According to journalist Chris Hedges, Zinn "steadfastly refused to cooperate in the anti-communist witchhunts in the 1950s."[78]

Later in the 1960s, as a result of Zinn's campaigning against the Vietnam War and his communication with Martin Luther King Jr., the FBI designated him a high security risk to the country by adding him to the Security Index, a list of American citizens who could be summarily arrested if a state of emergency were to be declared.[77][79] The FBI memos also show that they were concerned with Zinn's repeated criticism of the FBI for failing to protect black people against white mob violence. Zinn's daughter said she was not surprised by the files: "He always knew they had a file on him".[77]

Personal life and death

[edit]

Zinn married Roslyn Shechter in 1944. They remained married until her death in 2008. They had a daughter, Myla, and a son, Jeff. Myla is the wife of mindfulness instructor Jon Kabat-Zinn.[80]

Zinn was swimming in a hotel pool when he died of an apparent heart attack[81] in Santa Monica, California, on January 27, 2010, at the age of 87. He was scheduled to speak during an event which was titled "A Collection of Ideas... the People Speak" at the Crossroads School and the Santa Monica Museum of Art.[82]

In one of his last interviews,[83] Zinn stated that he would like to be remembered "for introducing a different way of thinking about the world, about war, about human rights, about equality," and

for getting more people to realize that the power which rests so far in the hands of people with wealth and guns, that the power ultimately rests in people themselves and that they can use it. At certain points in history, they have used it. Black people in the South used it. People in the women's movement used it. People in the anti-war movement used it. People in other countries who have overthrown tyrannies have used it.

He said he wanted to be known as "somebody who gave people a feeling of hope and power that they didn't have before."[84]

Notable recognition

[edit]- 2008 Howard Zinn was selected as a special senior advisor to Miguel d'Escoto Brockmann, the president of the United Nations General Assembly 63rd session.

- Established by a former Boston University student of Zinn's and two nonprofit organizations (Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change) while he was alive, the Zinn Education Project is Howard Zinn's legacy to middle- and high-school teachers and their students.[30] The project offers classroom teachers free lessons based on A People's History of the United States and like-minded history texts.

Awards

[edit]"I can't think of anyone who had such a powerful and benign influence. His historical work changed the way millions of people saw the past. The happy thing about Howard was that in the last years he could gain satisfaction that his contributions were so impressive and recognized."[6]

In 1991 the Thomas Merton Center for Peace and Social Justice in Pittsburgh awarded Zinn the Thomas Merton Award for his activism and work on national and international issues that transform our world.[85] For his leadership in the Peace Movement, Zinn received the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Award in 1996.[86] In 1998 he received the Eugene V. Debs Award,[87] the Firecracker Alternative Book Award in the Politics category for The Zinn Reader: Writings on Disobedience and Democracy,[88] and the Lannan Literary Award for nonfiction.[89] The following year he won the Upton Sinclair Award, which honors those whose work illustrates an abiding commitment to social justice and equality.[90]

In 2003, Zinn was awarded the Prix des Amis du Monde diplomatique for the French version of his seminal work, Une histoire populaire des Etats-Unis.[91]

On October 5, 2006, Zinn received the Haven's Center Award for Lifetime Contribution to Critical Scholarship in Madison, Wisconsin.[92]

Reception

[edit]In July 2013, the Associated Press revealed that Mitch Daniels, when he was the sitting Republican Governor of Indiana, asked for assurance from his education advisors that Zinn's works were not taught in K–12 public schools in the state.[93] The AP had gained access to Daniels' emails under a Freedom of Information Act request. Daniels also wanted a "cleanup" of K–12 professional development courses to eliminate "propaganda and highlight (if there is any) the more useful offerings."[94] In one of the emails, Daniels expressed contempt for Zinn upon his death:[95]

This terrible anti-American academic has finally passed away...The obits and commentaries mentioned his book, A People's History of the United States, is the 'textbook of choice in high schools and colleges around the country.' It is a truly execrable, anti-factual piece of disinformation that misstates American history on every page. Can someone assure me that it is not in use anywhere in Indiana? If it is, how do we get rid of it before more young people are force-fed a totally false version of our history?

At the time the emails were released, Daniels was serving as the president of Purdue University. In response, 90 Purdue professors issued an open letter expressing their concern.[96][97][98][99] Because of Daniels' attempt to remove Zinn's book, the former governor was accused of censorship, to which Daniels responded by saying that his views were misrepresented, and that if Zinn were alive and a member of the Purdue faculty, he would defend his free speech rights and right to publish. But he said that would not give Zinn an "entitlement to have that work foisted on school children in public schools."[100]

Stanford education professor Sam Wineburg has criticized Zinn's research. Wineburg acknowledged that A People's History of the United States was an important contribution for overlooked alternative perspectives, but criticised the book's coverage of the mid-thirties to the Cold War. According to reviewer David Plotnikoff from Stanford, Wineburg shows that "A People's History perpetrates the same errors of historical practice as the tomes it aimed to correct", for "Zinn's desire to cast a light on what he saw as historic injustice was a crusade built on secondary sources of questionable provenance, omission of exculpatory evidence, leading questions and shaky connections between evidence and conclusions".[101][102]

Daniel J. Flynn, an author and columnist at the conservative The American Spectator, wrote that Zinn's history was biased.[103] Michael Kazin, professor at Georgetown University and co-editor of the leftist magazine Dissent,, praised Zinn's A People's History of the United States for its dramatic condemnation of the exploitation of the masses by an elite few, and for its lavish use of quotes from social rebels and revolutionaries, though he describes it as somewhat simplified.[104] Kazin has also provided criticism saying "A People's History is bad history, albeit gilded with virtuous intentions. Zinn reduces the past to a Manichean fable."[105]

Mary Grabar, a resident fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization, accused Zinn of plagiarizing a polemic by novelist and anti-Vietnam War activist Hans Koning in The People's History, and editing Koning's narrative to remove what Grabar said was the "devout Catholic Columbus’s concern for the natives".[106][107]

In early 2017, lawmaker Kim Hendren attempted to ban books written by Zinn from Arkansas public schools.[108][109]

Bibliography

[edit]Author

[edit]- LaGuardia in Congress (1959; based on his 1958 Ph.D. dissertation Fiorello LaGuardia in Congress) OCLC 642325734.

- The Southern Mystique (1962) OCLC 423360.

- SNCC: The New Abolitionists (1964) OCLC 466264063.

- New Deal Thought (editor) (1965) OCLC 422649795.

- Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal (1967) OCLC 411235.

- Disobedience and Democracy: Nine Fallacies on Law and Order (1968, re-issued 2002) ISBN 978-0-89608-675-3.

- The Politics of History (1970) (2nd edition 1990) ISBN 978-0-252-06122-6.

- The Pentagon Papers Senator Gravel Edition. Vol. Five. Critical Essays. Boston. Beacon Press, 1972. 341p. plus 72p. of Index to Vol. I–IV of the Papers, Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, editors. ISBN 978-0-8070-0522-4.

- Justice in Everyday Life: The Way It Really Works (Editor) (1974) ISBN 978-0-688-00284-8.

- Justice? Eyewitness Accounts (1977) ISBN 978-0-8070-4479-7.

- — (2009). A People's History of the United States: 1492-present. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060528423. LCCN 2002032895. OCLC 699879349. OL 3563811M. Retrieved 8 July 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Klein, Maxine; Sargent, Lydia; — (1986). Playbook. South End Press. ISBN 978-0896083097. LCCN 86006754. OCLC 13116400. OL 2713846M.

- Declarations of Independence: Cross-Examining American Ideology (1991) ISBN 978-0-06-092108-8.[110]

- A People's History of the United States: The Civil War to the Present Kathy Emery and Ellen Reeves, Howard Zinn (2003 teaching edition) Vol. I: ISBN 978-1-56584-724-8. Vol II: ISBN 978-1-56584-725-5.

- Failure to Quit: Reflections of an Optimistic Historian (1993) ISBN 978-1-56751-013-3.

- You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times (autobiography)(1994) ISBN 978-0-8070-7127-4

- A People's History of the United States: The Wall Charts by Howard Zinn and George Kirschner (1995) ISBN 978-1-56584-171-0.

- Hiroshima: Breaking the Silence (pamphlet, 1995) ISBN 978-1-884519-14-7.

- The Zinn Reader: Writings on Disobedience and Democracy (1997) ISBN 978-1-888363-54-8; 2nd edition (2009) ISBN 978-1-58322-870-8.

- The Cold War & the University: Toward an Intellectual History of the Postwar Years (Noam Chomsky (Editor) Authors: Ira Katznelson, R. C. Lewontin, David Montgomery, Laura Nader, Richard Ohmann,[111] Ray Siever, Immanuel Wallerstein, Howard Zinn (1997) ISBN 978-1-56584-005-8.

- Marx in Soho: A Play on History (1999) ISBN 978-0-89608-593-0.

- The Future of History: Interviews With David Barsamian (1999) ISBN 978-1-56751-157-4.

- Howard Zinn on War (2000) ISBN 978-1-58322-049-8.

- Howard Zinn on History (2000) ISBN 978-1-58322-048-1.

- La Otra Historia De Los Estados Unidos (2000) ISBN 978-1-58322-054-2.

- Three Strikes: Miners, Musicians, Salesgirls, and the Fighting Spirit of Labor's Last Century (Dana Frank, Robin Kelley, and Howard Zinn) (2002) ISBN 978-0-8070-5013-2.

- Terrorism and War (2002) ISBN 978-1-58322-493-9. (interviews, Anthony Arnove (Ed.))

- The Power of Nonviolence: Writings by Advocates of Peace Editor (2002) ISBN 978-0-8070-1407-3.

- Emma: A Play in Two Acts About Emma Goldman, American Anarchist (2002) ISBN 978-0-89608-664-7.

- Artists in Times of War (2003) ISBN 978-1-58322-602-5.

- The 20th century: A People's History (2003) ISBN 978-0-06-053034-1.

- A People's History of the United States: Teaching Edition Abridged (2003 updated) ISBN 978-1-56584-826-9.

- Passionate Declarations: Essays on War and Justice (2003) ISBN 978-0-06-055767-6.

- Iraq Under Siege, The Deadly Impact of Sanctions and War, co-author (2003)

- Howard Zinn On Democratic Education Donaldo Macedo, Editor (2004) ISBN 978-1-59451-054-0.

- The People Speak: American Voices, Some Famous, Some Little Known (2004) ISBN 978-0-06-057826-8.

- Voices of a People's History of the United States (with Anthony Arnove, 2004) ISBN 978-1-58322-647-6; 2nd edition (2009) ISBN 978-1-58322-916-3.

- A People's History of the Civil War: Struggles for the Meaning of Freedom by David Williams, Howard Zinn (Series Editor) (2005) ISBN 978-1-59558-018-4.

- A Power Governments Cannot Suppress (2006) ISBN 978-0-87286-475-7.

- Original Zinn: Conversations on History and Politics (2006) Howard Zinn and David Barsamian.

- A People's History of American Empire (2008) by Howard Zinn, Mike Konopacki and Paul Buhle. ISBN 978-0-8050-8744-4.

- A Young People's History of the United States, adapted from the original text by Rebecca Stefoff; illustrated and updated through 2006, with new introduction and afterword by Howard Zinn; two volumes, Seven Stories Press, New York, 2007.

- Vol. 1: Columbus to the Spanish–American War. ISBN 978-1-58322-759-6.

- Vol. 2: Class Struggle to the War on Terror. ISBN 978-1-58322-760-2.

- One-volume edition (2009) ISBN 978-1-58322-869-2.

- The Bomb (City Lights Publishers, 2010) ISBN 978-0-87286-509-9.

- The Historic Unfulfilled Promise (City Lights Publishers, 2012) ISBN 978-0-87286-555-6.

- Howard Zinn Speaks: Collected Speeches 1963-2009 (Haymarket Books, 2012) ISBN 978-1-60846-259-9.

- Truth Has a Power of Its Own: Conversations About A People's History by Howard Zinn and Ray Suarez (The New Press, 2019) ISBN 978-1-62097-517-6.

Contributor

[edit]- Ars Americana Ars Politica: Partisan Expression in Contemporary American Literature and Culture. by Peter Swirski (2010) ISBN 978-0-7735-3766-8.

- Admirable Radical: Staughton Lynd and Cold War Dissent, 1945–1970 (2010), Kent State University Press by Carl Mirra ISBN 978-1-60635-051-5.

- A Gigantic Mistake by Mickey Z (2004) ISBN 978-1-930997-97-4.

- A People's History of the Supreme Court by Peter H. Irons (2000) ISBN 978-0-14-029201-5.

- A Political Dynasty In North Idaho, 1933–1967 by Randall Doyle (2004) ISBN 978-0-7618-2843-3.

- American Political Prisoners: Prosecutions Under the Espionage and Sedition Acts by Stephen M. Kohn (1994) ISBN 978-0-275-94415-5.

- American Power and the New Mandarins by Noam Chomsky (2002) ISBN 978-1-56584-775-0.

- Broken Promises Of America: At Home And Abroad, Past And Present: An Encyclopedia For Our Times by (Douglas F. Dowd (2004) ISBN 978-1-56751-313-4.

- Deserter From Death: Dispatches From Western Europe 1950–2000 by Daniel Singer (2005) ISBN 978-1-56025-642-7.

- Ecocide of Native America: Environmental Destruction of Indian Lands and Peoples by Donald Grinde, Bruce Johansen (1994) ISBN 978-0-940666-52-8.

- Eugene V. Debs Reader: Socialism and the Class Struggle by William A. Pelz (2000) ISBN 978-0-9704669-0-7.

- From a Native Son: Selected Essays in Indigenism, 1985–1995 by Ward Churchill (1996) ISBN 978-0-89608-553-4.

- Green Parrots: A War Surgeon's Diary by Gino Strada (2005) ISBN 978-88-8158-420-8.

- Hijacking Catastrophe: 9/11, Fear And The Selling Of American Empire by Sut Jhally editor, Jeremy Earp editor (2004) ISBN 978-1-56656-581-3.

- If You're Not a Terrorist...Then Stop Asking Questions! by Micah Ian Wright (2004) ISBN 978-1-58322-626-1.

- Iraq: The Logic of Withdrawal by Anthony Arnove (2006) ISBN 978-1-59558-079-5.

- Impeach the President: The Case Against Bush and Cheney Dennis Loo (Editor), Peter Phillips (Editor), Seven Stories Press: 2006 ISBN 978-1-58322-743-5.

- Life of an Anarchist: The Alexander Berkman Reader by Alexander Berkman Gene Fellner, editor (2004) ISBN 978-1-58322-662-9.

- Long Shadows: Veterans' Paths to Peace by David Giffey editor (2006) ISBN 978-1-891859-64-9.

- Masters of War: Latin America and United States Aggression from the Cuban Revolution Through the Clinton Years by Clara Nieto, Chris Brandt (trans) (2003) ISBN 978-1-58322-545-5.

- Peace Signs: The Anti-War Movement Illustrated by James Mann, editor (2004) ISBN 978-3-283-00487-3.

- Prayer for the Morning Headlines: On the Sanctity of Life and Death by Daniel Berrigan (poetry) and Adrianna Amari (photography) (2007) ISBN 978-1-934074-16-9.

- Silencing Political Dissent: How Post-9-11 Anti-terrorism Measures Threaten Our Civil Liberties by Nancy Chang, Center for Constitutional Rights (2002) ISBN 978-1-58322-494-6.

- Soldiers In Revolt: GI Resistance During The Vietnam War by David Cortright (2005) ISBN 978-1-931859-27-1.

- Sold to the Highest Bidder: The Presidency from Dwight D. Eisenhower to George W. Bush by Daniel M. Friedenberg (2002) ISBN 978-1-57392-923-3.

- The Autobiography of Abbie Hoffman Intro by Norman Mailer, Afterword by HZ (2000) ISBN 978-1-56858-197-2.

- The Case for Socialism by Alan Maass (2004) ISBN 978-1-931859-09-7.

- The Forging of the American Empire: From the Revolution to Vietnam, a History of U.S. Imperialism by Sidney Lens (2003) ISBN 978-0-7453-2101-1.

- The Higher Law: Thoreau on Civil Disobedience and Reform by Henry David Thoreau, Wendell Glick, editor (2004) ISBN 978-0-691-11876-5.

- The Iron Heel by Jack London (1971) ISBN 978-0-14-303971-6.

- The Sixties Experience: Hard Lessons about Modern America by Edward P. Morgan (1992) ISBN 978-1-56639-014-9.

- You Back the Attack, We'll Bomb Who We Want by Micah Ian Wright (2003) ISBN 978-1-58322-584-4.

- A People's History of the American Revolution by Ray Raphael (2002) ISBN 978-0-06-000440-8. Howard Zinn Foreword for New Press People's History Series.

Recordings

[edit]- A People's History of the United States (1999)

- Artists in the Time of War (2002)

- Heroes & Martyrs: Emma Goldman, Sacco & Vanzetti, and the Revolutionary Struggle (2000)

- Stories Hollywood Never Tells (2000)

- You Can't Blow Up A Social Relationship, CD including Zinn lectures and performances by rock band Resident Genius (Thick Records, 2005)[112]

Theatre

[edit]- Emma (1976)

- Daughter of Venus (1985)

- Marx in Soho (1999)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "HowardZinn.org". HowardZinn.org. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (1994). You can't be neutral on a moving train : a personal history of our times. Boston. ISBN 9780807071274. OCLC 50704670.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Powell, Michael (January 28, 2010). "Howard Zinn, Historian, Is Dead at 87". The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Glavin, Paul; Morse, Chuck (Spring 2003). "War is the Health of the State: An Interview with Howard Zinn". Perspectives on Anarchist Theory. 7 (1). Archived from the original on February 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Howard Zinn on Democratic Socialism on YouTube

- ^ a b Italie, Hillel (January 27, 2010). "Howard Zinn Dead, Author Of 'People's History Of The United States' Died At 87". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Howard Zinn". danjianbaowang.com. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Biography". HowardZinn.org. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Howard Zinn:-Chronicling Lives from Spelman College to Boston U." EducationUpdate.com. April 2004. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Duberman, Martin (2013). Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left. New Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9781595589347. Retrieved April 3, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Howard Zinn Describes Work in the Navy Yards". HowardZinn.org. December 8, 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (1990). The Politics of History (2nd ed.). University of Illinois Press. pp. 258–274. ISBN 978-0-252-01673-8.

- ^ "The Bomb" (PDF). Citylights.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (1990). Declarations of Independence. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 978-0-06-092108-8.

- ^ "La Libération de Royan avril 1945". C-royan.com. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "The Reception of the Presence of the U.S. Army in Pilsen in 1945 in Local Periodicals" (PDF). Dspace5.zcu.cz. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (1990). The Politics of History (2nd ed.). University of Illinois Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-252-01673-8.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (January 2006). "Interview with Zinn". Progressive.org. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ Zinn, Howard. Hiroshima: Breaking the Silence. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2008 – via polymer.bu.edu.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (December 2001). "A Just Cause, Not a Just War". The Progressive. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2012 – via Commondreams.org.

- ^ Powell, Michael (January 28, 2010). "Howard Zinn, Historian, Is Dead at 87". The New York Times. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (November 5, 2008). "What next for struggle in the Obama era?". SocialistWorker.org. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (March 1, 2005). "Changing minds, one at a time". The Progressive. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Duberman, Martin (2012). Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left. New Press. ISBN 9781595588401.

- ^ Cogswell, David (2009). Zinn for Beginners. For Beginners LLC. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-934389-40-9.

- ^ Activist, historian Howard Zinn dies at 87 by Ros Krasny at Reuters January 28, 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ^ Duberman (2012). Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left. The New Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-59558-840-1.

- ^ "National Book Awards 1981 - National Book Foundation". Nationalbook.org.

- ^ "Backlist to the Future" by Rachel Donadio, July 30, 2006.

- ^ a b "About the Zinn Education Project". Zinn Education Project. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "People's history moves small screen". Bu.edu. November 4, 2009. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ "The People Speak". Howardzinn.org. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ "The People Speak – Extended Edition: Contents". Zinn Education Project.

- ^ Dreier, Peter (June 26, 2012). The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame. PublicAffairs. p. 326. ISBN 9781568586816.

Howard Zinn participated in the Civil Rights Movement and lobbied with historian August Meier.

- ^ Lewis, David Levering (September 2003). "In Memoriam: August A. Meier". American Historical Association.

- ^ Polsgrove, Carol (2001). Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement. pp. 115, 196.

- ^ "In Memory: Howard Zinn and the Civil Rights Movement". Carol Polsgrove on Writers' Lives. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010.

- ^ Polsgrove. Divided Minds. p. 238. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Duberman (2012). Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left. The New Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-59558-840-1.

- ^ a b Duberman (2012). Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left. The New Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-59558-840-1.

- ^ Duberman (2012). Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left. The New Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-1-59558-840-1.

- ^ Walker, Alice (January 31, 2010). "Saying goodbye to my friend Howard Zinn". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 24, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Edelman, Marian Wright (2000). "Spelman College: A Safe Haven for a Young Black Woman". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (27 (Spring, 2000)): 118–123. doi:10.2307/2679028. JSTOR 2679028.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (1991). Declarations of Independence: Cross-Examining American Ideology. Perennial. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-0060921088.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (December 22, 2009). "Finishing School for Pickets". thenation.com. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Interview with Zinn". globetrotter.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ "My Name Is Freedom Albany, Georgia". zmag.org. Archived from the original on February 19, 1999.

- ^ "Media Filter article on Zinn". mediafilter.org. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ "Reporting Civil Rights, Part one: American Journalism 1941–1963". The Library of America. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ Birnbaum, Robert (January 10, 2001). "Howard Zinn Interview". Identity Theory. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ "Against Discouragement: Spelman College Commencement Address, May 2005 By Howard Zinn". Archived from the original on December 8, 2005.

- ^ Brittain, Victoria (January 28, 2010). "Howard Zinn's Lesson To Us All". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Tomgram: Graduation Day with Howard Zinn". Tomdispatch.com. May 24, 2005. Retrieved November 20, 2021. full text of "Against Discouragement."

- ^ "Howard Zinn (1922–2010): A Tribute to the Legendary Historian with Noam Chomsky, Alice Walker, Naomi Klein and Anthony Arnove". Democracy Now!. January 28, 2010.

- ^ Who Spoke Up? American Protest Against the War in Vietnam 1963–1975. Horizon Book Promotions. 1989. ISBN 978-0-385-17547-0.

- ^ "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest". New York Post. January 30, 1968.

- ^ Mirra], Carl (February 1, 2010). "Forty Years On: Looking Back at the 1969 Annual Meeting". Perspectives on History. American Historical Association.

- ^ Ellsberg autobiography, Zinn autobiography.

- ^ a b "Church Plans 4-Book Version of Pentagon Study". The New York Times. August 18, 1971. Archived from the original (fee required) on December 14, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ Kahn, George McT. (June 1975). "The Pentagon Papers: A Critical Evaluation". American Political Science Review. 69 (2): 675–684. doi:10.2307/1959096. JSTOR 1959096. S2CID 144419085.

- ^ a b "Resources". Top Secret: The Battle for the Pentagon Papers. Annenberg Center for Communication at University of Southern California. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2010). You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times. Beacon Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-8070-9549-2.

- ^ a b Blanton, Tom (May 21, 2006). "The lie behind the secrets". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Winter Soldier Investigation. 1971.

- ^ "Cineaste" (PDF). pp. 91, 96. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ Ellsberg, Daniel (January 28, 2010). "A Memory of Howard". Truthdig. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ "How 1971's Mayday actions rattled Nixon and helped keep Vietnam from becoming a forever war". April 29, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ "Disarm Staff". DISARM Education Fund. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Hamm, Theodore (Autumn 2002). "Howard Zinn in Conversation with Theodore Hamm". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ^ "Tomdispatch Interview: Howard Zinn, The Outer Limits of Empire". TomDispatch.com. September 8, 2005. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ Prager, Dennis. "What the left thinks: Howard Zinn, Part II". DennisPrager.com. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

DP: So do you feel that, by and large, the Zarqawi-world and the Bush-world are moral equivalents? HZ: I do.

- ^ "Zinn calls for activism". Yale Daily News. May 3, 2007. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ "American Historical Association Blog: Iraq War Resolution is Ratified by AHA Members". blog.historians.org. March 12, 2007. Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ Yu, Lea. "Historian Howard Zinn Calls for Activism". CommonDreams.org. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ Zirin, Dave (January 28, 2010). "Howard Zinn: The Historian Who Made History". The Huffington Post. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ Merrefield, Clark (July 30, 2010). "The Daily Beast".

Zinn, who died in January and was best known for his influential A People's History of the United States, was studying at New York University on the GI Bill when J. Edgar Hoover's FBI opened its first files on him. He was working as vice chairman for the Brooklyn branch of the American Labor Party and living at 926 Lafayette Avenue in what is an area now considered the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn.

- ^ a b c d Matthew Rothschild (July 31, 2010). "The FBI's File on Howard Zinn". The Progressive.

- ^ Hedges, Chris (August 1, 2010). "Why the Feds Fear Thinkers Like Howard Zinn". Truthdig. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ "FBI Records: The Vault — Howard Zinn". vault.fbi.gov. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- ^ Feeney, Mark; Marquard, Brian (January 28, 2010), "Historian-activist Zinn dies", Boston.com, retrieved December 28, 2016

- ^ Powell, Michael (January 28, 2010). "Howard Zinn, Historian, Is Dead at 87". The New York Times. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Lopez, Robert J. (January 28, 2010). "Zinn dies at 87; author of best-selling People's History of the United States: Activist collapsed in Santa Monica, where he was scheduled to deliver a lecture". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Howard Zinn | Historian | Big Think". Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ "Howard Zinn: How I Want to Be Remembered". Commondreams.org. January 29, 2010. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Past thomas merton awardees". Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ "57th recipient of the INT'L COURAGE OF CONSCIENCE AWARD - Howard Zinn". Peaceabbey.org. May 2, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ "Eugene V Debs Foundation Member Awards". Archived from the original on May 5, 2008. Retrieved April 2, 2009.. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ^ "The Zinn Reader". Sevenstories.com. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Lannan Foundation – Howard Zinn". Lannan.org.

- ^ "Awards - Howard Zinn". Howardzinn.org. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ "Prix des Amis du Monde diplomatique 2003 – Les Amis du Monde diplomatique". Amis.monde-diplomatique.fr. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ "Zinn to receive Havens Center award (October 4, 2006)". News.wisc.edu. October 4, 2006.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (July 17, 2013). "E-mails reveal censorship efforts by Mitch Daniels as Indiana governor". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ LoBianco, Tom (September 15, 2013). "Mitch Daniels Sought To Censor Public Universities, Professors" (PDF). The Huffington Post. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Ohlheiser, Abby (July 16, 2013). "Former Governor, Now Purdue President, Wanted Howard Zinn Banned in Schools". Atlantic Wire. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Cohen, Robert; Sonia Murrow (August 5, 2013). "Who's Afraid of Radical History?". The Nation. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Franck, Mathew (July 23, 2013). "Mitch Daniels Can Count". First Things. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ LoBianco, Tom (July 22, 2013). "Purdue profs 'troubled' by Mitch Daniels' Zinn comments". News-sentinel.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "Censoring Howard Zinn: Former Indiana Gov. Tried to Remove 'A People's History' from State Schools". Democracy Now. July 22, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Mikaelian, Allen (September 1, 2013). "The Mitch Daniels Controversy". Perspectives on History: The Newsmagazine of the American Historical Association. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- ^ Plotnikoff, David (December 20, 2012). "Zinn's influential history textbook has problems, says Stanford education expert". Stanford University News. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Wineburg, Sam. "Undue Certainty" (PDF). American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Flynn, Daniel J. (June 9, 2003). "Howard Zinn's Biased History". History News Network. George Mason University. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Kazin, Michael (Fall 2019). "Can Conservatives Write Good U.S. History?". Dissent Magazine. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Kazin, Michael (February 9, 2010). "Howard Zinn's Disappointing History of the United States". History News Network. George Washington University. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Grabar, Mary (July 13, 2020). "Scholar disputes source of criticism of Columbus (Commentary)". Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ Grabar 2020b.

- ^ "House Bill 1834- For An Act To Be Entitled An Act to Prohibit a Public School District or Open-Enrollment Public Charter School from Including in Its Curriculum or Course Materials for a Program of Study Books or Any Other Material Authored by or Concerning Howard Zinn; and for Other Purposes" (PDF). arkleg.state.ar.us. Arkansas State Legislature. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ "Bill introduced to ban Howard Zinn books from Arkansas public schools". March 2, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (1990),"Declarations of independence: cross-examining American ideology", HarperCollins.

- ^ "Politics of Knowledge: Richard Ohmann". UPNE. January 21, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ^ "Howard Zinn, Resident Genius - You Can't Blow Up A Social Relationship". Discogs.com. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Duberman, Martin. Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left. (The New Press, 2012).

- Ellis, Deb and Mueller, Denis. Howard Zinn: You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train. (film 2004)

- FRF's Judith Mizrachy interviews Deb Ellis and Denis Mueller, directors of the film Howard Zinn: You can't be neutral on a moving train at the Wayback Machine (archived May 7, 2006). Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- Grabar, Mary (2020b). Debunking Howard Zinn: Exposing the Fake History That Turned a Generation against America. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 9781684511525.

- Greenberg, David. "Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn's influential mutilations of American history", The New Republic March 19, 2013

- Joyce, Davis D. Howard Zinn: A Radical American Vision. (Prometheus Books, 2003).

- Lynd, Staughton. Doing History from the Bottom Up; On E.P. Thompson, Howard Zinn, and Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014.

Interviews

[edit]- 2001 Interview with Howard Zinn about A People's History of the United States, religion, and movies

- Interview with Guernica: a magazine of arts and politics.

- The Tavis Smiley Show: "Howard Zinn and the Omissions of U.S. History", November 27, 2003, National Public Radio.

- An Interview with Howard Zinn on Anarchism: Rebels Against Tyranny by AK Press

- "War is the Health of the State: An Interview with Howard Zinn", By Paul Glavin & Chuck Morse, Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, Vol. 7, No. 1, Spring 2003

- "A Great Faith in Human Beings." In Klin, Richard and Lily Prince (photos), Something to Say: Thoughts on Art and Politics in America. (Leapfrog Press, 2011)

Obituaries

[edit]- Helene Atwan, director of Beacon Press on "The Loss of Howard Zinn" January 29, 2010.

- Howard Zinn, Historian, is Dead at 87, By Michael Powell, The New York Times, January 28, 2010

- Obituary[usurped] in the Oxonian Review

Videos

[edit]- The Legacy of Howard Zinn – video by Big Think

- Howard Zinn on why there are no just wars: "Holy Wars" – video by Democracy Now!

- Empire or Humanity?: What the Classroom Didn't Teach Me about the American Empire on YouTube; by Howard Zinn; Narrated by Viggo Mortensen

- Howard Zinn's talk to teachers at the 2008 National Conference for the Social Studies (NCSS) hosted by the Zinn Education Project

- Zinn Speaking About his Book ~ A Power Governments Cannot Suppress – one-hour speech by C-SPAN

- Howard Zinn on Marxism, Anarchism, and the Paris Commune on YouTube interviewed by Sasha Lilley, November 5, 2009

- "Howard Zinn (1922–2010): A Tribute to the Legendary Historian with Noam Chomsky, Alice Walker, Naomi Klein and Anthony Arnove", Democracy Now!, January 28, 2010

- American Feud: A History of Conservatives and Liberals documentary featuring interviews with Howard Zinn and others

- Zinn on Class in America – Interview series on The Real News (TRNN) (6 videos) – April 2009

- Interview with Howard Zinn Media Education Foundation (MEF) – July 2005

- The Power of Story: The People Speak on YouTube at The 2020 Sundance Film Festival

External links

[edit]- HowardZinn.org

- Works by or about Howard Zinn at the Internet Archive

- Column archive at The Progressive

- Howard Zinn at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- "Howard Zinn", FBI Records: The Vault, vault.fbi.gov

- Zinn Education Project

- "My Grades Will Not Be Instruments of War"

- Howard Zinn Papers, Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University Special Collections

Historian Howard Zinn dies at age 87 at Wikinews

Historian Howard Zinn dies at age 87 at Wikinews "Genius" award recipient and other luminaries campaigning for worldwide renunciation of war at Wikinews

"Genius" award recipient and other luminaries campaigning for worldwide renunciation of war at Wikinews

- 1922 births

- 2010 deaths

- 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century American essayists

- 20th-century American historians

- 20th-century American philosophers

- 21st-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 21st-century American essayists

- 21st-century American historians

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American philosophers

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- Alternative Tentacles artists

- American anarchists

- American anti–Vietnam War activists

- American anti-war activists

- American democratic socialists

- American feminist writers

- American humanists

- American male dramatists and playwrights

- American male non-fiction writers

- American Marxists

- American media critics

- American memoirists

- American people of Austrian-Jewish descent

- American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- American political scientists

- American political writers

- American tax resisters

- American anti-capitalists

- Anti-American sentiment in the United States

- Anti-consumerists

- Boston University faculty

- Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Feminist historians

- G7 Welcoming Committee Records artists

- Harvard University staff

- Historians of anarchism

- Historians of communism

- Historians of the United States

- Jewish American dramatists and playwrights

- Jewish American historians

- Jewish American social scientists

- Jewish anarchists

- Jewish feminists

- Jewish socialists

- American male feminists

- American feminists

- Military personnel from New York City

- New York University alumni

- People from Middlesex County, Massachusetts

- American philosophers of culture

- American philosophers of education

- Philosophers of history

- Philosophers of war

- Secular humanists

- Deaths from coronary thrombosis

- American socialist feminists

- Spelman College faculty

- Theorists on Western civilization

- Thomas Jefferson High School (Brooklyn) alumni

- United States Army Air Forces officers

- United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II

- Writers from Brooklyn

- Writers from Massachusetts

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American male writers