Leeds Town Hall

| Leeds Town Hall | |

|---|---|

Leeds Town Hall in 2006 | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Classical/baroque |

| Town or city | Leeds |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 53°48′01″N 1°32′59″W / 53.8003°N 1.5497°W |

| Construction started | August 1853 |

| Opened | 7 September 1858 |

| Cost | £41,835 |

| Client | Corporation of Leeds |

| Height | 225 ft (69 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 5,600 sq yd (4,700 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Cuthbert Brodrick |

| Main contractor | Samuel Atack |

| Website | |

| www | |

Leeds Town Hall was built between 1853 and 1858 on The Headrow (formerly Park Lane), Leeds, West Yorkshire, England, to a design by architect Cuthbert Brodrick. It was planned to include law courts, a council chamber, a public hall, a suite of ceremonial entertaining rooms and municipal offices. With the building of the Civic Hall in 1933 some of those functions moved away and it became essentially a public hall and law courts.[1]

Leeds Town Hall is one of the largest town halls in the United Kingdom and as of 2017[update] it is the thirteenth tallest building in Leeds. It was opened by Queen Victoria, in a lavish ceremony in 1858 as Leeds celebrated the completion of an important civic structure. It is a Grade I listed building.[2]

With a height of 225 feet (68.6 m) it was the tallest building in Leeds from its construction in 1858 until 1966, when it lost the title to the Park Plaza Hotel, which stands 8 metres (26 ft) taller at 77 metres (253 ft). It has held the title longer than any other building, a record 108 years. The distinctive clock tower, which serves as a symbol of Leeds was not part of the initial design but was added by Brodrick in 1856 as the civic leaders sought to make an even grander statement.

Description

The town hall is classical in style but baroque in imaginative power and drama. It stands squarely at the top of a flight of steps (altered from their original shape) on a mound made specially for the purpose of increasing its commanding position. The whole facade is made of giant columns and all the sides reflect that pattern. The central portico has ten huge Corinthian columns. Then there is an immense frieze and rising above it all, the clock tower, 225 ft (69 m) high, which was not in the original design.[1] The carving of the tympanum around the entrance, the work of the prolific Victorian sculptor John Thomas, represents Leeds encouraging the arts and sciences. The four Portland stone lions on plinths along the frontage, an 1867 addition by the sculptor William Day Keyworth Jr,[3] were modelled at London Zoo, and contrast with the sandstone of the building itself.[1]

The Victoria Hall - originally the 'Great Hall' - rises to 92 ft (28 m) inside the parallelogram of surrounding rooms and corridors and the enclosing colonnades. The striking internal decoration to the design of London decorator John Crace,[4] cut-glass chandelier and the then-largest organ in Europe led one writer to say that it was "the best place in Britain to see what it looked like on the inside of a wedding cake."[5]

The town hall provided accommodation for municipal departments, a courtroom, police station or 'central charge office', and a venue for concerts and civic events. It still has a role as a council office, although many departments have been relocated. The principal performance space, the richly decorated Victoria Hall, is a venue for orchestral concerts.

History

Background

Until 1813, the Moot Hall, on Briggate was the seat of Leeds Corporation and was used for judicial purposes from 1615. Leeds went through a period of rapid growth in the first half of the 19th century and by the mid-19th century it became apparent that the court house was no longer large enough for the functions it performed; it was demolished in 1825 and replaced by a new court house on Park Row, Leeds.[6]

In July 1850, Leeds Corporation held a public meeting, the decision of which was that a "large public hall" should be built in Leeds. A council committee was established to assess the opinions of Leeds' inhabitants. One year later, it presented a report, with consultees including Joseph Paxton, the designer of The Crystal Palace, and delegations to other large towns including Manchester and Liverpool to investigate their plans for building public halls. The report's recommendations also identified a site for the hall on what was then Park Lane, now the Headrow.[7] This site was on the edge of the town centre of the time, but required a large parcel of land that was unavailable in the congested central streets. It was purchased from a wealthy merchant named John Blayds for the sum of £9,500.[8]

In order to finance the town hall, the council proposed to sell shares in the building to the value of £10 but little public interest was shown. The council then proposed introducing a specific rate levied to fund its construction. A decision was deferred until after the municipal election of November 1850 to give ratepayers a chance to express their views. The town hall was approved in January 1851 when the motion was put to the council and it was carried by twenty-four votes to twelve.[9] The resolution read: "As the attempt to raise funds by public subscription has failed, it is the opinion of this Council desirable to erect a Town Hall, including suitable corporate buildings."[7] It was intended to represent Leeds' emergence as an important industrial centre during the Industrial Revolution and symbolize civic pride and confidence.

No one would wish to underestimate the importance of the metropolis, but, after all, it is not in London that we find the best specimens of our English architecture ... It is in what were once provincial cities or hamlets that we discover the most venerable and the most striking memorials of the taste and self-consecration of our forefathers. And the time may come when the archaeologist of a future age will look for the best specimens of the buildings of the present reign, not to the Law Courts or in the Houses of Parliament, but to some provincial towns, where possibly the hurry and rush of life have not been as great as in the capital.

Construction

Design

Leeds Corporation tendered for designs from architects in 1852, in an open competition. Sir Charles Barry, at the time still occupied rebuilding the Palace of Westminster, was selected to advise the Town Hall Committee in their judging. The contract was won by Cuthbert Brodrick, an young architect from Hull who was unknown outside his home town. He had travelled extensively in Europe in 1844-5 and acquired a love for its classical architecture. He was only twenty-nine when he won the competition for the town hall.[10] Second place in the competition was given to the partners Henry Francis Lockwood and William Mawson, who had designed St George's Hall, Bradford in 1849, and later went on to build Bradford City Hall in 1869.[11]

The Town Hall Committee initially had reservations after selecting Brodrick; asking Charles Barry for an affirmation in Brodrick's abilities in the construction of such a large building, mostly relating to him being so young, Barry responded that he was "fully satisfied that the Council might trust [Brodrick] with the most perfect safety." Next, the Committee took the unusual step of insisting in a clause in Brodrick's contract stating that he would receive no payment beyond that of the accepted estimate of £39,000 if the work costs exceeded it. Brodrick agreed to this clause, and a sub-committee was formed to "superintend the progress of the works".[7]

Building works

The foundation stone was laid in August 1853, by the Mayor of Leeds, John Hope Shaw. Sizeable crowds were present at the ceremony and subsequent speeches, which were followed by a long procession consisting of brass bands, Brodrick, military officers, members of the Council, and others. Celebrations continued with a civic banquet, festivities on Woodhouse Moor, and fireworks.[12]

Over the next couple of years, the design was revised many times during the construction of the building; such as the inclusion of an organ and the extension of the vestibule. The most controversial modification was the inclusion of a tower. A design of a tower by Brodrick, which would cost £6,000, was rejected in February 1853, but it was debated at great length and the proposal resurfaced in September 1854 with a limitation of cost to £7,000, but this was again defeated by the Council. Opponents of the tower used the argument that "a tower would cost money and would only be good to look at, not to use". Proponents were thinking of the Continental associations of a grand and impressive town hall. There were hopes that visitors would come to Leeds to see the Town Hall, and that a tower, at a few additional thousand pounds, would provide the building with beauty beyond mere utilitarianism. The following February, a compromise was reached when the Council voted to allow "a form of roof construction which might eventually permit the erection of a tower 'if at any time it should be thought desirable to do so.'" It was not until March 1856 that the tower was formally approved by a majority of nineteen.[7] It would take the form of a cupola supported on columns akin to the Corinthian columns of the south facade, but the tower was not completed until after the Town Hall's official opening, with a bell cast by John Warner & Sons hung in 1860.[13]

On 25 July 1853, the building contract was awarded to Samuel Atack, a Leeds builder and bricklayer. Work began in July, using millstone grit from 17 different quarries. Rawdon Hill stone was favoured for those parts of the building on which there would be carving; Derbyshire gritstone formed many of the columns.[13] The Council had originally granted £39,000 for construction, but Atak's contract was for a sum of £41,835 - a cost increase caused by Leeds choosing to build its town hall during a period of rising prices of labour and building materials. Various other problems beset the project: Atack's main problems as the builder were changes in design and difficulties with the architect; the Crimean War, because army recruitment caused a shortage of workmen and a rise in wages; and deadline pressures arising from Queen Victoria's agreement to open the building. These ultimately led to his bankruptcy in March 1857; various other local contractors were appointed to complete the Town Hall.[7] Leeds Town Hall was subject to much criticism during its construction. The original estimated costs were vastly exceeded and the corporation had to find extra funding at a time when there was great poverty among the Leeds' working classes.

Opening

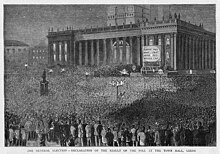

Arrangements for the Town Hall's opening were made well in advance. On 6 September 1858, the Queen arrived at Leeds Central railway station, met by crowds estimated to number 400,000 to 600,000.[14] The Corporation had even established a sub-committee for street decorations - flags, banners and streamers lined the streets of the city. She stayed the night at the home of the Mayor, Peter Fairbairn, Woodsley House, with tight military security.

On 7 September, the building was completed, save for the tower bell, and was officially opened by Queen Victoria and Albert. She proceeded from the Mayor's home down Woodhouse Lane to the city centre and along to the top of East Parade where a triumphal arch had been constructed. After entering the building, she knighted the Mayor, and then the hall was declared open on her behalf by the Prime Minister, the Earl of Derby. Later, the Queen was escorted to Wellington station to travel north to Balmoral.[14]

The day was combined with an exhibition of local manufactures, held in the Cloth Hall, and a music festival, which opened with Mendelson's Elijah and closed with Handel's Messiah. Police were reinforced from the West Riding, Bradford, London and Birmingham.[10]

20th century

During the war the town hall housed an ARP post in the crypt and from 1942 a British Restaurant, which proved popular after the war, being refurbished in 1960 before closing in 1966.[15]

On 14 and 15 March 1941, Leeds was bombed by the Luftwaffe. Houses were destroyed in Bramley, Burley, Armley and Beeston and bombs dropped on the city centre, hitting the east side of the town hall causing significant damage to its roof and walls on Calverley Street.[16] The damage was repaired shortly after.[17]

In 1993, Leeds Crown Court opened on Westgate, ending the town hall's role as a courthouse. The town hall's cells also closed ending an arrangement where a public concert may happen simultaneously in a building while prisoners are being held. During its time as a Leeds Assizes and later Leeds Crown Court it held various notable cases including the conviction and life-sentencing of Stefan Kiszko for the murder of Leslie Molseed in 1976 (later quashed) and the conviction of Zsiga Pankotia for the murder of Jack Eli Myers in 1961 who became the last man to be hanged at Armley Gaol.

For much of the 20th century, the Town Hall was left blackened by soot and smoke from the industrial city surrounding it. In spring 1972 the building was given its first official clean up - on previous occasions it had been hosed down by the fire brigade - which revealed much of the detailed stonework.[13] This was not before a heated debate, as Leeds Civic Trust strongly opposed it preferring that its blackness "should stand as a symbol of the city's industrial past and as a reminder to future generations of the air pollution which the city is so successfully combatting."[18]

Leeds Civic Hall was commissioned by Leeds Corporation in a Keynesian project intended to provide work for the local unemployed. The Civic Hall opened in 1933 as the seat of Leeds City Council. Since then the Town Hall has been used for civic events such as concerts rather than council meetings.

Present usage and popular culture

The town hall hosts concerts and formal civic functions, including a register office. Conferences, weddings and civil partnerships take place in the Albert or Brodrick Suites which have been converted from the former courtrooms. The hall has played host to prayer meetings, light entertainment, wrestling matches, auctions and dances.[19]

Several recurring cultural events use the Town Hall such as Leeds International Concert Season, the triennial Leeds International Piano Competition.[20], regular lunchtime organ recitals,[19] and the Leeds International Film Festival.[21][22] Other events include Leeds International Beer Festival, a four-day annual festival celebrating and promoting craft beer.[23]

Leeds Town hall has been used for filming several films and television programmes. It stood in for the Palace of Westminster in close up shots in the Yorkshire Television series The New Statesman[citation needed] and was used in the opening scenes of the 2016 film Dad's Army.[24]

Appraisal

Leeds Town Hall has been used as a model for civic buildings across Britain and the British Empire.

In a 1960s BBC film about the changing architecture of Leeds, poet John Betjeman, known for his love of Victorian architecture, praised the town hall.[25] On 29 November 2008, Leeds Town Hall and the town halls of Halifax, Paisley, Burslem, Hornsey, Manchester, Lynton, Dunfermline, Fordwich and Much Wenlock were selected as the "ten town halls to visit" by Architecture Today. It commented: The epitome of northern civic bombast, Leeds' municipal palace has a grandeur that helps sustain the city's sense of its own importance. Its architect, Cuthbert Broderick, also contributed the Corn Exchange and City Museum before disappearing into obscurity.[26]

Gallery

Plans and documentation

-

Park Lane (now The Headrow) in 1847. A small park lies on the site of the town hall

-

A map showing Park House (the site of the town hall) in 1852

-

First drawing for the proposed town hall

-

Plan of the town hall

Interior

-

Ceiling of the entrance hall

-

Interior showing the pipe organ

See also

- List of tallest buildings and structures in Leeds

- Architecture of Leeds

- Leeds Civic Hall, the replacement building for Leeds City Council's civic functions

- Parliament House, Melbourne, a building some believe to be heavily based on Leeds Town Hall

References

- ^ a b c Linstrum, Derek (1969). Historic Architecture of Leeds. Leeds Civic Trust. p. 54.

- ^ Historic England. "TOWN HALL, Leeds - 1255772 (1255772)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "Queen Victoria, 1858". Leodis - a photographic archive of Leeds. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Sheeran, George (1993). Leeds: The Architectural Heritage. Ryburn. p. 50. ISBN 978-1853310584.

- ^ Morgan, John (2006). A Celebration of Leeds. Great Northern. ISBN 9781905080212.

- ^ Chrystal, Paul (2016). Leeds in 50 Buildings. Amberley. ISBN 9781445654553.

- ^ a b c d e f Briggs, Asa (24 March 1993). Victorian Cities. University of California Press. pp. 157–183. ISBN 9780520079229.

- ^ Ibbotson, Nigel. Leeds City Beautiful. Breedon. pp. 9–21. ISBN 9781859836781.

- ^ "Origins: Discovering Leeds Town Hall". Leeds City Council. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ a b Puttgens, Patrick (1979). Leeds: The Back to Front, Inside Out, Upside Down City. Stile Books. p. 32. ISBN 0906886007.

- ^ Banerjee, Jacqueline. "Bradford Town Hall by Lockwood & Mawson". Victorian Web. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Laying the Foundation Stone: Discovering Leeds Town Hall". Leeds City Council. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Mitchell, W. R. (2000). A History of Leeds. Phillimore. pp. 109–113.

- ^ a b Tuffrey, Peter (18 November 2014). "Cheers for Victoria at town hall opening". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Wartime: Discovering Leeds Town Hall". Leeds City Council. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ Skilbeck, Helen. "Town Hall Terror". The Secret Library. Leeds Libraries and Information Service. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ "Leeds in World War 2". mylearning. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Steven Burt, Kevin Grady (2002). The Illustrated History of Leeds (2 ed.). Breedon. p. 237.

- ^ a b "Present Day: Discovering Leeds Town Hall". Leeds City Council. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "History". Leeds International Piano Comp. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ Robinson, Paul (5 October 2012). "Opening titles ready to roll on 2012 Leeds International Film Festival". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "30th Leeds International Film Festival". Leeds City Council. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Leeds International Beer Festival Returns to Town Hall". Leeds-List. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "Dad's Army" (PDF). Local Government Association. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Leeds International Film Festival". Leeds International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ten town halls to visit". Daily Telegraph. 29 November 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

Further reading

- Wrathmell, Susan; Minnis, John (2005). Leeds (Pevsner Architectural Guides). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 60–67. ISBN 0-300-10736-6.

- Briggs, Asa (24 March 1993). Victorian Cities. University of California Press. pp. 157–183. ISBN 9780520079229.