Millennials

| Part of a series on |

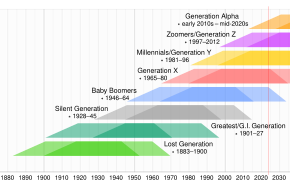

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

Millennials, also known as Generation Y or Gen Y, are the generational demographic cohort following Generation X and preceding Generation Z. There are no precise dates for when this cohort starts or ends; demographers and researchers typically use the early 1980s as starting birth years and the mid-1990s to early 2000s as ending birth years. Millennials are sometimes referred to as "echo boomers" due to a major surge in birth rates in the 1980s and 1990s, and because millennials are often the children of the baby boomers. Although millennial characteristics vary by region, depending on social and economic conditions, the generation is generally marked by an increased use and familiarity with communications, media, and digital technologies.[citation needed]

Terminology

Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe are widely credited with naming the millennials.[1] They coined the term in 1987, around the time children born in 1982 were entering preschool, and the media were first identifying their prospective link to the new millennium as the high school graduating class of 2000.[2] They wrote about the cohort in their books Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069 (1991)[3] and Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation (2000).[2]

In August 1993, an Advertising Age editorial coined the phrase Generation Y to describe those who were aged 11 or younger as well as the teenagers of the upcoming ten years who were defined as different from Generation X.[4][5] According to journalist Bruce Horovitz, in 2012, Ad Age "threw in the towel by conceding that millennials is a better name than Gen Y",[1] and by 2014, a past director of data strategy at Ad Age said to NPR "the Generation Y label was a placeholder until we found out more about them".[6] Millennials are sometimes called Echo Boomers,[7] due to their being the offspring of the baby boomers and due to the significant increase in birth rates from the early 1980s to mid 1990s, mirroring that of their parents. In the United States, birth rates peaked in August 1990[8][9] and a 20th-century trend toward smaller families in developed countries continued.[10][11] In his book The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom, author Elwood Carlson called this cohort the "New Boomers".[12]

Psychologist Jean Twenge described millennials as "Generation Me" in her 2006 book Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled – and More Miserable Than Ever Before, which was updated in 2014.[13][14] In 2013, Time magazine ran a cover story titled Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation.[15] Newsweek used the term Generation 9/11 to refer to young people who were between the ages of 10 and 20 years during the terrorist acts of 11 September 2001. The first reference to "Generation 9/11" was made in the cover story of the 12 November 2001 issue of Newsweek.[16] Alternative names for this group proposed include Generation We,[17] Global Generation, Generation Next[18] and the Net Generation.[19]

Chinese millennials are commonly called the 1980s and 1990s generations. At a 2015 conference in Shanghai organized by University of Southern California's US-China Institute, millennials in China were examined and contrasted with American millennials.[20] Findings included millennials' marriage, childbearing, and child raising preferences, life and career ambitions, and attitudes towards volunteerism and activism.[21]

Date and age range definitions

A minority of demographers and researchers start the generation in the mid-to-late 1970s, such as MetLife which uses birth dates ranging 1977–1994,[22] and Nielsen Media Research which uses the earliest dates from 1977 and the latest dates 1995 or 1996.[23][24][25]

The majority of researchers and demographers start the generation in the early 1980s, with some ending the generation in the mid-1990s. Australia's McCrindle Research[26] uses 1980–1994 as Generation Y birth years. A 2013 PricewaterhouseCoopers[27] report used 1980 to 1995. Gallup Inc.,[28][29][30] and MSW Research[31] use 1980–1996. Ernst and Young uses 1981–1996.[32]

A 2018 report from Pew Research Center defines millennials as born from 1981 to 1996, choosing these dates for "key political, economic and social factors", including September 11th terrorist attacks. This range makes Millennials 5 to 20 years old at the time of the attacks so "old enough to comprehend the historical significance." Pew indicated they would use 1981 to 1996 for future publications but would remain open to date recalibration.[33]

Some end the generation in the late 1990s or early 2000s. United States Census Bureau defines the millennial generation as those born from 1982–2000.[34] Goldman Sachs,[35] Resolution Foundation,[36][37] all use 1980–2000. SYZYGY, a digital service agency partially owned by WPP, uses 1981–1998,[38][39]. The Asia Business Unit of Corporate Directions, Inc describes millennials as born between 1981-2000,[40] The United States Chamber of Commerce uses 1980-1999[41]. The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary describes millennials as those born roughly between the 1980s and 1990s.[42]

A 2013 Time magazine cover story used 1980 or 1981 as start dates.[43]

Demographers William Straus and Neil Howe who are widely credited with coining the term, define millennials as born between 1982–2004.[1] However, Howe described the dividing line between millennials and the following Generation Z as "tentative", saying "you can’t be sure where history will someday draw a cohort dividing line until a generation fully comes of age". He noted that the millennials' range beginning in 1982 would point to the next generation's window starting between 2000 and 2006.[44]

In his 2008 book The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom, author Elwood Carlson defined this cohort as born between 1983–2001, based on the upswing in births after 1983 and finishing with the "political and social challenges" that occurred after the September 11 terrorist acts.[12] In 2016, U.S PIRG described millennials as those born between 1983 and 2000.[45][46][47] On the American television program Survivor, for their 33rd season, subtitled Millennials vs. Gen X, the "Millennial tribe" consisted of individuals born between 1984 and 1997.[48]

Due to birth-year overlap between definitions of Generation X and millennials, some individuals born in the late 1970s and early 1980s see themselves as being "between" the two generations.[49][50][51][52] Names given to those born in the Generation X and millennial cusp years include Xennials, Generation Catalano, and the Oregon Trail Generation.[52][53][54][55][56]

Traits

Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe believe that each generation has common characteristics that give it a specific character with four basic generational archetypes, repeating in a cycle. According to their hypothesis, they predicted millennials will become more like the "civic-minded" G.I. Generation with a strong sense of community both local and global.[2] Strauss and Howe ascribe seven basic traits to the millennial cohort: special, sheltered, confident, team-oriented, conventional, pressured, and achieving. Arthur E. Levine, author of When Hope and Fear Collide: A Portrait of Today's College Student describes these generational images as "stereotypes".[57]

Strauss and Howe's research has been influential, but it also has critics.[57] Psychologist Jean Twenge says Strauss and Howe's assertions are overly-deterministic, non-falsifiable, and unsupported by rigorous evidence. Twenge, the author of the 2006 book Generation Me, considers millennials, along with younger members of Generation X, to be part of what she calls "Generation Me".[58] Twenge attributes millennials with the traits of confidence and tolerance, but also describes a sense of entitlement and narcissism, based on personality surveys showing increased narcissism among millennials compared to preceding generations when they were teens and in their twenties. She questions the predictions of Strauss and Howe that this generation will turn out civic-minded.[59][60] A 2016 study by SYZYGY a digital service agency, found millennials in the U.S. continue to exhibit elevated scores on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory as they age, finding millennials exhibited 16% more narcissism than older adults, with males scoring higher on average than females. The study examined two types of narcissism: grandiose narcissism, described as "the narcissism of extraverts, characterized by attention-seeking behavior, power and dominance", and vulnerable narcissism, described as "the narcissism of introverts, characterized by an acute sense of self-entitlement and defensiveness."[38][39][61]

The University of Michigan's "Monitoring the Future" study of high school seniors (conducted continually since 1975) and the American Freshman survey, conducted by UCLA's Higher Education Research Institute of new college students since 1966, showed an increase in the proportion of students who consider wealth a very important attribute, from 45% for Baby Boomers (surveyed between 1967 and 1985) to 70% for Gen Xers, and 75% for millennials. The percentage who said it was important to keep abreast of political affairs fell, from 50% for Baby Boomers to 39% for Gen Xers, and 35% for millennials. The notion of "developing a meaningful philosophy of life" decreased the most across generations, from 73% for Boomers to 45% for millennials. The willingness to be involved in an environmental cleanup program dropped from 33% for Baby Boomers to 21% for millennials.[62] Millennials show a willingness to vote more than previous generations. With voter rates being just below 50% for the last four presidential cycles, they have already surpassed Gen Xers of the same age who were at just 36%.[63]

A 2013 Pew Research Poll found that 84% of millennials, born since 1980, who were at that time between the ages of 18 and 32, favored legalizing the use of marijuana.[64] In 2015, the Pew Research Center also conducted research regarding generational identity that said a majority did not like the "millennial" label.[65]

In March 2014, the Pew Research Center issued a report about how "millennials in adulthood" are "detached from institutions and networked with friends."[66][67] The report said millennials are somewhat more upbeat than older adults about America's future, with 49% of millennials saying the country’s best years are ahead though they're the first in the modern era to have higher levels of student loan debt and unemployment.

Fred Bonner, a Samuel DeWitt Proctor Chair in Education at Rutgers University and author of Diverse Millennial Students in College: Implications for Faculty and Student Affairs, believes that much of the commentary on the Millennial Generation may be partially accurate, but overly general and that many of the traits they describe apply primarily to "white, affluent teenagers who accomplish great things as they grow up in the suburbs, who confront anxiety when applying to super-selective colleges, and who multitask with ease as their helicopter parents hover reassuringly above them." During class discussions, Bonner listened to black and Hispanic students describe how some or all of the so-called core traits did not apply to them. They often said that the "special" trait, in particular, is unrecognizable. Other socio-economic groups often do not display the same attributes commonly attributed to millennials. "It's not that many diverse parents don't want to treat their kids as special," he says, "but they often don't have the social and cultural capital, the time and resources, to do that."[57]

In his book Fast Future, author David Burstein describes millennials' approach to social change as "pragmatic idealism" with a deep desire to make the world a better place, combined with an understanding that doing so requires building new institutions while working inside and outside existing institutions.[68]

Elza Venter, an educational psychologist and lecturer at Unisa, South Africa, in the Department of Psychology of Education, believes members of Generation Y are digital natives because they have grown up experiencing digital technology and have known it all their lives. Prensky [69] coined the concept ‘digital natives’ because this generation are ‘native speakers of the digital language of computers, video games and the internet’. This generation spans 20 years and its older members use a combination of face-to-face communication and computer mediated communication, while its younger members use mainly electronic and digital technologies for interpersonal communication.[70]

Workplace attitudes

There are vast, and conflicting, amounts of literature and empirical studies discussing the existence of generational differences as it pertains to the workplace.[71] The majority of research concludes millennials differ from both their generational cohort predecessors, and can be characterized by a preference for a flat corporate culture, an emphasis on work-life balance and social consciousness.[qualify evidence]

According to authors from Florida International University, original research performed by Howe and Strauss as well as Yu & Miller suggest Baby Boomers resonate primarily with loyalty, work ethic, steady career path, and compensation when it comes to their professional lives.[72] Generation X on the other hand, started shifting preferences towards an improved work-life balance with a heightened focus on individual advancement, stability, and job satisfaction.[72] Meanwhile, millennials place an emphasis on producing meaningful work, finding a creative outlet, and have a preference for immediate feedback.[72] In the article "Challenges of the Work of the Future," it is also stressed that millennials working at the knowledge-based jobs very often assume personal responsibility in order to make the most of what they do. As they are not satisfied with remaining for a long period of time at the same job, their career paths become more dynamic and less predictable.[73] Findings also suggest the introduction of social media has augmented collaborative skills and created a preference for a team-oriented environment.[72]

In the 2010 the Journal of Business and Psychology, contributors Myers and Sadaghiani find millennials "expect close relationships and frequent feedback from supervisors" to be a main point of differentiation.[74] Multiple studies observe millennials’ associating job satisfaction with free flow of information, strong connectivity to supervisors, and more immediate feedback.[74] Hershatter and Epstein, researchers from Emory University, argue a lot of these traits can be linked to millennials entering the educational system on the cusp of academic reform, which created a much more structured educational system.[75] Some argue in the wake of these reforms, such as the No Child Left Behind Act, millennials have increasingly sought the aid of mentors and advisers, leading to 66% of millennials seeking a flat work environment.[75]

Hershatter and Epstein also stress a growing importance on work-life balance. Studies show nearly one-third of students' top priority is to "balance personal and professional life".[75] The Brain Drain Study shows nearly 9 out of 10 millennials place an importance on work-life balance, with additional surveys demonstrating the generation to favor familial over corporate values.[75] Studies also show a preference for work-life balance, which contrasts to the Baby Boomers' work-centric attitude.[74]

Data also suggests millennials are driving a shift towards the public service sector. In 2010, Myers and Sadaghiani published research in the Journal of Business and Psychology stating heightened participation in the Peace Corps and AmeriCorps as a result of millennials, with volunteering being at all-time highs.[74] Volunteer activity between 2007 and 2008 show the millennial age group experienced almost three-times the increase of the overall population, which is consistent with a survey of 130 college upperclassmen depicting an emphasis on altruism in their upbringing.[74] This has led, according to a Harvard University Institute of Politics, six out of ten millennials to consider a career in public service.[74]

The 2014 Brookings publication shows a generational adherence to corporate social responsibility, with the National Society of High School Scholars (NSHSS) 2013 survey and Universum’s 2011 survey, depicting a preference to work for companies engaged in the betterment of society.[76] Millennials' shift in attitudes has led to data depicting 64% of millennials would take a 60% pay cut to pursue a career path aligned with their passions, and financial institutions have fallen out of favor with banks comprising 40% of the generation's least liked brands.[76]

In 2008, author Ron Alsop called the millennials "Trophy Kids,"[77] a term that reflects a trend in competitive sports, as well as many other aspects of life, where mere participation is frequently enough for a reward. It has been reported that this is an issue in corporate environments.[77] Some employers are concerned that millennials have too great expectations from the workplace.[78] Some studies predict they will switch jobs frequently, holding many more jobs than Gen Xers due to their great expectations.[79] Psychologist Jean Twenge reports data suggests there are differences between older and younger millennials regarding workplace expectations, with younger millennials being "more practical" and "more attracted to industries with steady work and are more likely to say they are willing to work overtime" which Twenge attributes to younger millennials coming of age following the financial crisis of 2007–2008.[80]

There is also a contention that the major differences are found solely between millennials and Generation X. Researchers from the University of Missouri and The University of Tennessee conducted a study based on measurement equivalence to determine if such a difference does in fact exist.[81] The study looked at 1,860 participants who had completed the Multidimensional Work Ethic Profile (MWEP), a survey aimed at measuring identification with work-ethic characteristics, across a 12-year period spanning from 1996 to 2008.[81] The results of the findings suggest the main difference in work ethic sentiments arose between the two most recent generational cohorts, Generation X and millennials, with relatively small variances between the two generations and their predecessor, the Baby Boomers.[81]

That said, some research fails to find convincing differences. A meta study conducted by researchers from The George Washington University and The U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences questions the validity of workplace differences across any generational cohort. According to the researchers, disagreement in which events to include when assigning generational cohorts, as well as varied opinions on which age ranges to include in each generational category are the main drivers behind their skepticism.[82] The analysis of 20 research reports focusing on the three work-related factors of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and intent to turn over proved any variation was too small to discount the impact of employee tenure and aging of individuals.[82] Newer research shows that millennials change jobs for the same reasons as other generations—namely, more money and a more innovative work environment. They look for versatility and flexibility in the workplace, and strive for a strong work–life balance in their jobs[83] and have similar career aspirations to other generations, valuing financial security and a diverse workplace just as much as their older colleagues.[84]

Political views

Surveys of political attitudes among millennials in the United Kingdom have suggested increasingly social liberal views, as well as higher overall support for classical liberal economic policies than preceding generations. They are more likely to support same-sex marriage and the legalization of drugs.[85] The Economist parallels this with millennials in the United States, whose attitudes are more supportive of social liberal policies and same-sex marriage relative to other demographics.[85] They are also more likely to oppose animal testing for medical purposes than older generations.[86] Pew Research described millennials as "the force of the youth vote" and as part of the political conversation which helped elect the first U.S. black president, describing millennials as between 12 and 27 during the 2008 U.S Presidential election.[33]

Bernie Sanders, a self-proclaimed democratic socialist and democratic candidate in the 2016 United States presidential election, was the most popular candidate among millennial voters in the primary phase, having garnered more votes from people under 30 in 21 states than the major parties' candidates, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, did combined.[87] In April 2016, The Washington Post viewed him as changing the way millennials viewed politics, saying, "He's not moving a party to the left. He's moving a generation to the left."[88][89] Bernie Sanders referred to millennials as "the least prejudiced generation in the history of the United States".[90] A 2014 poll for the libertarian Reason magazine suggested that American millennials were social liberals and fiscal centrists, more often than their global peers.[91]

In the United Kingdom, the majority of millennials opposed the British withdrawal from the European Union. Blaming Baby boomers, who largely supported the referendum, one commenter said: "The younger generation has lost the right to live and work in 27 other countries. We will never know the full extent of the lost opportunities, friendships, marriages and experiences we will be denied."[92][93][94][95] The Washington Post phrased this as "we let you steal our future", reporting high voter turnout among those over 55 years of age and low voter turnout among those under 34 years of age.[96][97][98][99][100]

Attitudes

Neil Howe believes that a defining trait of millennials is that they are more likely to support political correctness than members of older generations.[101] In 2015, a Pew Research study found 40% of millennials in the United States supported government restriction of public speech offensive to minority groups. Support for restricting offensive speech was lower among older generations, with 27% of Gen Xers, 24% of Baby Boomers, and only 12% of the Silent Generation supporting such restrictions. Pew Research noted similar age related trends in the United Kingdom, but not in Germany and Spain, where millennials were less supportive of restricting offensive speech than older generations. In France, Italy and Poland no significant age differences were observed.[102] In the U.S. and UK, millennials have brought changes to higher education via drawing attention to microaggressions and advocating for implementation of safe spaces and trigger warnings in the university setting. Critics of such changes have raised concerns regarding their impact on free speech, asserting these changes can promote censorship, while proponents have described these changes as promoting inclusiveness.[101][103][104]

Demographics in the United States

Millennial population size varies, depending on the definition used. William Strauss and Neil Howe projected in their 1991 book Generations that the U.S. millennial population would be 76 million.[105] Later,[when?] using dates ranging from 1982 to 2004, Neil Howe revised the number to over 95 million people (in the U.S.).[citation needed] In a 2012 Time magazine article, it was estimated that there were approximately 80 million U.S. millennials.[106] The United States Census Bureau, using birth dates ranging from 1982 to 2000, stated the estimated number of U.S. millennials in 2015 was 83.1 million people.[107]

In 2016, the Pew Research Center found that millennials surpassed Baby Boomers to become the largest living generation in the United States. By analyzing 2015 U.S Census data they found there were 75.4 million millennials, based on Pew's definition of the generation which ranges from 1981 to 1997, compared to 74.9 million Baby Boomers.[108][109]However with their revised end date of 1996, millennials are expected to surpass boomers in size in 2019.[110]

Economic prospects

Economic prospects for some millennials have declined largely due to the Great Recession in the late 2000s.[111][112][113] Several governments have instituted major youth employment schemes out of fear of social unrest due to the dramatically increased rates of youth unemployment.[114] In Europe, youth unemployment levels were very high (56% in Spain,[115] 44% in Italy,[116] 35% in the Baltic states, 19% in Britain[117] and more than 20% in many more countries). In 2009, leading commentators began to worry about the long-term social and economic effects of the unemployment.[118] Unemployment levels in other areas of the world were also high, with the youth unemployment rate in the U.S. reaching a record 19% in July 2010 since the statistic started being gathered in 1948.[119] In Canada, unemployment among youths in July 2009 was 16%, the highest it had been in 11 years.[120] Underemployment is also a major factor. In the U.S. the economic difficulties have led to dramatic increases in youth poverty, unemployment, and the numbers of young people living with their parents.[121] In April 2012, it was reported that half of all new college graduates in the US were still either unemployed or underemployed.[122] It has been argued that this unemployment rate and poor economic situation has given millennials a rallying call with the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement.[123] However, according to Christine Kelly, Occupy is not a youth movement and has participants that vary from the very young to very old.[124]

A variety of names have emerged in various European countries hard hit following the financial crisis of 2007–2008 to designate young people with limited employment and career prospects.[125] These groups can be considered to be more or less synonymous with millennials, or at least major sub-groups in those countries. The Generation of €700 is a term popularized by the Greek mass media and refers to educated Greek twixters of urban centers who generally fail to establish a career. In Greece, young adults are being "excluded from the labor market" and some "leave their country of origin to look for better options". They're being "marginalized and face uncertain working conditions" in jobs that are unrelated to their educational background, and receive the minimum allowable base salary of €700 per month. This generation evolved in circumstances leading to the Greek debt crisis and some participated in the 2010–2011 Greek protests.[126] In Spain, they're referred to as the mileurista (for €1,000 per month),[127] in France "The Precarious Generation,[128]" and as in Spain, Italy also has the "milleurista"; generation of 1,000 euros (per month).[125]

In 2015, millennials in New York City were reported as earning 20% less than the generation before them, as a result of entering the workforce during the great recession. Despite higher college attendance rates than Generation X, many were stuck in low-paid jobs, with the percentage of degree-educated young adults working in low-wage industries rising from 23% to 33% between 2000 and 2014.[129] In 2016, research from the Resolution Foundation found millennials in the UK earned £8,000 less in their 20s than Generation X, describing millennials as "on course to become the first generation to earn less than the one before".[130][131]

Generation Flux is a neologism and psychographic (not demographic) designation coined by Fast Company for American employees who need to make several changes in career throughout their working lives due to the chaotic nature of the job market following the Great Recession. Societal change has been accelerated by the use of social media, smartphones, mobile computing, and other new technologies.[132] Those in "Generation Flux" have birth-years in the ranges of both Generation X and millennials. "Generation Sell" was used by author William Deresiewicz to describe millennials' interest in small businesses.[133]

Millennials are expected to make up approximately half of the U.S. workforce by 2020. Millennials are the most highly educated and culturally diverse group of all generations, and have been regarded as hard to please when it comes to employers.[134] To address these new challenges, many large firms are currently studying the social and behavioral patterns of millennials and are trying to devise programs that decrease intergenerational estrangement, and increase relationships of reciprocal understanding between older employees and millennials. The UK's Institute of Leadership & Management researched the gap in understanding between millennial recruits and their managers in collaboration with Ashridge Business School.[135] The findings included high expectations for advancement, salary and for a coaching relationship with their manager, and suggested that organizations will need to adapt to accommodate and make the best use of millennials. In an example of a company trying to do just this, Goldman Sachs conducted training programs that used actors to portray millennials who assertively sought more feedback, responsibility, and involvement in decision making. After the performance, employees discussed and debated the generational differences they saw played out.[77]

Millennials have benefited the least from the economic recovery following the Great Recession, as average incomes for this generation have fallen at twice the general adult population's total drop and are likely to be on a path toward lower incomes for at least another decade. A Bloomberg L.P. article wrote that "Three and a half years after the worst recession since the Great Depression, the earnings and employment gap between those in the under-35 population and their parents and grandparents threatens to unravel the American dream of each generation doing better than the last. The nation's younger workers have benefited least from an economic recovery that has been the most uneven in recent history."[136]

In 2014, millennials were entering an increasingly multi-generational workplace.[137] Even though research has shown that millennials are joining the workforce during a tough economic time they still have remained optimistic, as shown when about nine out of ten millennials surveyed by the Pew Research Center said that they currently have enough money or that they will eventually reach their long-term financial goals.[138]

Peter Pan generation

American sociologist Kathleen Shaputis labeled millennials as the Boomerang Generation or Peter Pan generation, because of the members' perceived tendency for delaying some rites of passage into adulthood for longer periods than most generations before them. These labels were also a reference to a trend toward members living with their parents for longer periods than previous generations.[139] Kimberly Palmer regards the high cost of housing and higher education, and the relative affluence of older generations, as among the factors driving the trend.[140] Questions regarding a clear definition of what it means to be an adult also impacts a debate about delayed transitions into adulthood and the emergence of a new life stage, Emerging Adulthood. A 2012 study by professors at Brigham Young University found that college students were more likely to define "adult" based on certain personal abilities and characteristics rather than more traditional "rite of passage" events.[141] Larry Nelson noted that "In prior generations, you get married and you start a career and you do that immediately. What young people today are seeing is that approach has led to divorces, to people unhappy with their careers … The majority want to get married […] they just want to do it right the first time, the same thing with their careers."[141] Their expectations have had a dampening effect on millennials' rate of marriage.

A 2013 joint study by sociologists at the University of Virginia and Harvard University found that the decline and disappearance of stable full-time jobs with health insurance and pensions for people who lack a college degree has had profound effects on working-class Americans, who now are less likely to marry and have children within marriage than those with college degrees.[142] Data from a 2014 study of U.S. millennials revealed over 56% of this cohort considers themselves as part of the working class, with only approximately 35% considering themselves as part of the middle class; this class identity is the lowest polling of any generation.[143]

Research by the Urban Institute conducted in 2014, projected that if current trends continue, millennials will have a lower marriage rate compared to previous generations, predicting that by age 40, 31% of millennial women will remain single, approximately twice the share of their single Gen X counterparts. The data showed similar trends for males.[144][145] A 2016 study from Pew Research showed millennials delay some activities considered rites of passage of adulthood with data showing young adults aged 18–34 were more likely to live with parents than with a relationship partner, an unprecedented occurrence since data collection began in 1880. Data also showed a significant increase in the percentage of young adults living with parents compared to the previous demographic cohort, Generation X, with 23% of young adults aged 18–34 living with parents in 2000, rising to 32% in 2014. Additionally, in 2000, 43% of those aged 18–34 were married or living with a partner, with this figure dropping to 32% in 2014. High student debt is described as one reason for continuing to live with parents, but may not be the dominant factor for this shift as the data shows the trend is stronger for those without a college education. Richard Fry, a senior economist for Pew Research said of millennials, "they're the group much more likely to live with their parents." furthering "they're concentrating more on school, careers and work and less focused on forming new families, spouses or partners and children".[146][147]

According to a cross-generational study comparing millennials to Generation X conducted at Wharton School of Business, more than half of millennial undergraduates surveyed do not plan to have children. The researchers compared surveys of the Wharton graduating class of 1992 and 2012. In 1992, 78% of women planned to eventually have children dropping to 42% in 2012. The results were similar for male students. The research revealed among both genders the proportion of undergraduates who reported they eventually planned to have children had dropped in half over the course of a generation.[148][149][150]

Religion

In the U.S., millennials are the least likely to be religious when compared to older generations.[151] There is a trend towards irreligion that has been increasing since the 1940s.[152] 29 percent of Americans born between 1983 and 1994 are irreligious, as opposed to 21 percent born between 1963 and 1981, 15 percent born between 1948 and 1962 and only 7 percent born before 1948.[153] A 2005 study looked at 1,385 people aged 18 to 25 and found that more than half of those in the study said that they pray regularly before a meal. One-third said that they discussed religion with friends, attended religious services, and read religious material weekly. Twenty-three percent of those studied did not identify themselves as religious practitioners.[154] A Pew Research Center study on millennials shows that of those between 18–29 years old, only 3% of these emerging adults self-identified as "atheists" and only 4% self-identified as "agnostics". Overall, 25% of millennials are "Nones" and 75% are religiously affiliated.[155]

Over half of millennials polled in the United Kingdom in 2013 said they had "no religion nor attended a place of worship", other than for a wedding or a funeral. 25% said they "believe in a God", while 19% believed in a "spiritual greater power" and 38% said they did not believe in God nor any other "greater spiritual power". The poll also found 41% thought religion was "the cause of evil" in the world more often than good.[156] The British Social Attitudes Survey found that 71% of British 18–24 year-olds were not religious, with just 3% affiliated to the once-dominant Church of England.[157]

Digital technology

In their 2007 book, authors Junco and Mastrodicasa expanded on the work of William Strauss and Neil Howe to include research-based information about the personality profiles of millennials, especially as it relates to higher education. They conducted a large-sample (7,705) research study of college students. They found that Next Generation college students, born between 1983–1992, were frequently in touch with their parents and they used technology at higher rates than people from other generations. In their survey, they found that 97% of these students owned a computer, 94% owned a mobile phone, and 56% owned an MP3 player. They also found that students spoke with their parents an average of 1.5 times a day about a wide range of topics. Other findings in the Junco and Mastrodicasa survey revealed 76% of students used instant messaging, 92% of those reported multitasking while instant messaging, 40% of them used television to get most of their news, and 34% of students surveyed used the Internet as their primary news source.[158][159] Older millennials came of age prior to widespread usage and availability of smartphones, defined as those born 1988 and earlier, in contrast to younger millennials, those born in 1989 and later, who were exposed to this technology in their teen years.[80]

Gen Xers and millennials were the first to grow up with computers in their homes. In a 1999 speech at the New York Institute of Technology, Microsoft Chairman and CEO Bill Gates encouraged America's teachers to use technology to serve the needs of the first generation of kids to grow up with the Internet.[160] Some millennials enjoy having hundreds of channels from cable TV. However, some other millennials do not even have a TV, so they watch media over the Internet using smartphones and tablets.[161] One of the most popular forms of media use by millennials is social networking. In 2010, research was published in the Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research which claimed that students who used social media and decided to quit showed the same withdrawal symptoms of a drug addict who quit their stimulant.[162] Marc Prensky coined the term "digital native" to describe "K through college" students in 2001, explaining they "represent the first generations to grow up with this new technology."[163] Millennials are identified as "digital natives" by the Pew Research Center which conducted a survey titled Millennials in Adulthood.[67]

Millennials use social networking sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, etc..., to create a different sense of belonging, make acquaintances, and to remain connected with friends.[164] In the Frontline episode "Generation Like" there is discussion about millennials, their dependence on technology, and the ways the social media sphere is commoditized.[165]

Cultural identity

Strauss & Howe's book titled Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation describes the millennial generation as "civic-minded", rejecting the attitudes of the Baby Boomers and Generation X.[166] Since the 2000 U.S. Census, which allowed people to select more than one racial group, millennials in abundance have asserted the ideal that all their heritages should be respected, counted, and acknowledged.[167][168] Millennials are the children of Baby Boomers or Generation X, while some older members may have parents from the Silent Generation. A 2013 poll in the United Kingdom found that Generation Y was more "open-minded than their parents on controversial topics".[156][169] Of those surveyed, nearly 75% supported same-sex marriage.

A 2013 Pew Research Poll found that 84% of millennials, born since 1980, who were at that time between the ages of 18 and 32, favored legalizing the use of marijuana.[64] In 2015, the Pew Research Center also conducted research regarding generational identity.[65] It was discovered that millennials are less likely to strongly identify with the generational term when compared to Generation X or to the Baby Boomers, with only 40% of those born between 1981 and 1997 identifying as part of the Millennial Generation. Among older millennials, those born 1981–1988, Pew Research found 43% personally identified as members of the older demographic cohort, Generation X, while only 35% identified as millennials. Among younger millennials (born 1989–1997), generational identity was not much stronger, with only 45% personally identifying as millennials. It was also found that millennials chose most often to define themselves with more negative terms such as self-absorbed, wasteful or greedy. In this 2015 report, Pew defined millennials with birth years ranging from 1981 onwards.[65]

Millennials came of age in a time where the entertainment industry began to be affected by the Internet.[170][171][172] In addition to millennials being the most ethnically and racially diverse compared to the generations older than they are, they are also on pace to be the most formally educated. As of 2008[update], 39.6% of millennials between the ages of 18 and 24 were enrolled in college, which was an American record. Along with being educated, millennials also tend to upbeat. As stated above in the economic prospects section, about 9 out of 10 millennials feel as though they have enough money or that they will reach their long-term financial goals, even during the tough economic times, and they are more optimistic about the future of the U.S. Additionally, millennials are also more open to change than older generations. According to the Pew Research Center that did a survey in 2008, millennials are the most likely of any generation to self-identify as liberals and are also more supportive of progressive domestic social agenda than older generations. Finally, millennials are less overtly religious than the older generations. About one in four millennials are unaffiliated with any religion, a considerably higher ratio than that of older generations when they were the ages of millennials.[138]

See also

- Demographics of the United States

- Generation gap

- Generation Snowflake

- List of generations

- Psychological effects of Internet use

- Adolescence

- Youth bulge

References

- ^ a b c Horovitz, Bruce (4 May 2012). "After Gen X, Millennials, what should next generation be?". USA Today. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ a b c Strauss, William; Howe, Neil (2000). Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation. Cartoons by R.J. Matson. New York: Vintage Original. p. 370. ISBN 0375707190. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ Strauss, William; Howe, Neil (1991). Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0688119126. p. 335

- ^ "Generation Y" Ad Age 30 August 1993. p. 16.

- ^ Francese, Peter (1 September 2003). "Trend Ticker: Ahead of the Next Wave". Advertising Age. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

Today's 21-year-olds, who were born in 1982 and are part of the leading edge of Generation Y, are among the most-studied group of young adults ever.

- ^ Samantha Raphelson (6 October 2014). "From GIs To Gen Z (Or Is It iGen?): How Generations Get Nicknames". NPR. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Armour, Stephanie (6 November 2008). "Generation Y: They've arrived at work with a new attitude". USA Today. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ Advance Report of Final Natality Statistics, 1990, Monthly Vital Statistics Report, 25 February 1993

- ^ "Baby Boom – A History of the Baby Boom". Geography.about.com. 9 August 1948. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Rosenthal, Elisabeth (4 September 2006). "European Union's Plunging Birthrates Spread Eastward". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ a b Carlson, Elwood (2008). The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom. Springer. p. 29. ISBN 978-1402085406.

- ^ Twinge, Jean (30 September 2014). "Generation Me – Revised and Updated: Why Today's Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled – and More Miserable Than Ever Before". Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "College students think they're so special – Study finds alarming rise in narcissism, self-centeredness in 'Generation Me'". NBC News. 27 February 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ Stein, Joel (20 May 2013). "Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation". Time. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ Kalb, Claudia (September 2009). "Generation 9/11". Newsweek. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ Generation We. How Millennial Youth Are Taking Over America And Changing Our World Forever

- ^ "The Online NewsHour: Generation Next". PBS. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Shapira, Ian (6 July 2008). "What Comes Next After Generation X?". The Washington Post. pp. C01. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ University of Southern California US-China Institute University of Southern California, 2015

- ^ "Video: #MillennialMinds". University of Southern California. 2015.

- ^ "Demographic Profile – America's Gen Y" (PDF). MetLife. 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Millennials: Much Deeper Than Their Facebook Pages". www.nielsen.com. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ "Millennials: Breaking the Myths". www.nielsen.com. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ "how celebs and brands can get in game with gen z". Nielsen Media Research. 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Generations Defined. Mark McCrindle

- ^ PwC; University of Southern California and the London Business School (2013). "PwC's NextGen: A global generational study" (PDF). PwC's NextGen: A global generational study. PwC. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

{{cite web}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ Inc., Gallup,. "How Hotels Can Engage Gen X and Millennial Guests". Gallup.com. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Inc., Gallup,. "Millennial Banking Customers: Two Myths, One Fact". Gallup.com. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Inc., Gallup,. "Insurance Companies Have a Big Problem With Millennials". Gallup.com. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Igniting Millennial Engagement: Supervising Similarities, Distinctions, and Realities" (PDF). Dale Carnegie Training. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Americas retail report: Redefining loyalty for retail" (PDF). www.ey.com. EY. June 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Defining generations: Where Millennials end and post-Millennials begin". www.pewresearch.org. Pews Research Center. March 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Bureau, US Census. "Millennials Outnumber Baby Boomers and Are Far More Diverse".

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Millennials Coming of Age". Goldman Sachs. 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Millennials 'set to earn less than Generation X'". BBC. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ "Millennials facing 'generational pay penalty' as their earnings fall £8,000 behind during their 20s". Resolution Foundation. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Technology-Driven Millennials Remain Narcissistic as They Age". PR Newswire. 20 October 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ a b "EGOTECH". SYZYGY. October 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ "The Thai Market to Watch and Their Players: Generation Y – The Driving Force of Consumption Trends in Thailand". Corporate Directions Inc. 15 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ "The Millennial Generation Research Review". The United States Chamber of Commerce. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "Definition of millennial". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Stein, Joel (20 May 2013). "The Me Me Me Generation". Time. p. 30. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Howe, Neil (27 October 2014). "Introducing the Homeland Generation (Part 1 of 2)". Forbes. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Millennials Drive Less". US PIRG. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ "Millennnials Shift Away from Driving". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ "Why are Millennials Forgoing Driving". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ Ross, Dalton (22 September 2016). "Survivor: Millennials vs. Gen X premiere recap: 'May the Best Generation Win'". Entertainment Weekly's EW.com. Time Warner, Inc. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Ingraham, Christopher (5 May 2015). "Five really good reasons to hate millennials". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Mukherji, Rohini (29 July 2014). "X or Y: A View from the Cusp". www.apexpr.com. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Epstein, Leonora (17 July 2013). "22 Signs You're Stuck Between Gen X And Millennials". www.buzzfeed.com. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ a b Garvey, Ana (5 May 2015). "The Biggest (And Best) Difference Between Millennial and My Generation". Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Fogarty, Lisa (7 January 2016). "3 Signs you're stuck between Gen X & Millennials". www.sheknows.com. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Shafrir, Doree (28 March 2016). "Generation Catalano". Slate. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ Stankorb, Sarah (25 September 2014). "Reasonable People Disagree about the Post-Gen X, Pre-Millennial Generation". Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Garvey, Anna. "Why '80s Babies Are Different Than Other Millennials".

- ^ a b c Hoover, Eric (11 October 2009). "The Millennial Muddle: How stereotyping students became a thriving industry and a bundle of contradictions". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ Twenge, Jean M. (2006). Generation Me. New York: Free Press (Simon & Schuster). ISBN 978-0743276979.

- ^ Twenge, Jean M. (2007). "Generation me: Why today's young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled – and more miserable than ever before". ISBN 978-0743276986.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Twenge, JM; Campbell, WK; Freeman, EC (2012). "Generational Differences in Young Adults' Life Goals, Concern for Others, and Civic Orientation, 1966–2009" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 102 (5): 1045–1062. doi:10.1037/a0027408. PMID 22390226.

- ^ Longman, Molly (22 October 2016). "Survey: Iowa millennials not as narcissistic as rest of U.S." The Des Moines Register. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ Healy, Michelle (15 March 2012). "Millennials might not be so special after all, study finds". USA Today. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Galston, William A. (31 July 2017). "Millennials will soon be the largest voting bloc in America".

- ^ a b "Majority Now Supports Legalizing Marijuana". Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 4 April 2013.

- ^ a b c "Most Millennials Resist the 'Millennial' Label". Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "Millennials in Adulthood – Detached from Institutions, Networked with Friends" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Millennials in Adulthood". Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project. 7 March 2014.

- ^ Burstein, David (2013). Fast Future: How the Millennial Generation is Shaping Our World. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 3

- ^ Prensky, M. (2001). "Digital natives, digital immigrants": Part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6.

- ^ Elza Venter (5 January 2017). "Bridging the communication gap between Generation Y and the Baby Boomer generation" Retrieved 8 January 2018

- ^ Bell, D'Vaughn (July 2017). "Major Gen X & Gen Y Workplace Differences". Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Huyler, Debaro; Pierre, Yselande; Ding, Wei; Norelus, Adly. "Millennials in the Workplace: Positioning Companies for Future Success".

- ^ Bondar, Kateryna. "Challenges of the Work of the Future". InnovaCima. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Myers, Karen K.; Sadaghiani, Kamyab (1 January 2010). "Millennials in the Workplace: A Communication Perspective on Millennials' Organizational Relationships and Performance". Journal of Business and Psychology. 25 (2): 225–238. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9172-7. JSTOR 40605781. PMC 2868990. PMID 20502509.

- ^ a b c d Hershatter, Andrea; Epstein, Molly (1 January 2010). "Millennials and the World of Work: An Organization and Management Perspective". Journal of Business and Psychology. 25 (2): 211–223. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9160-y. JSTOR 40605780.

- ^ a b Winograd, Morley; Hais, Michael. "How Millennials Could Upend Wall Street and Corporate America | Brookings Institution". Brookings. Brookings Institution.

- ^ a b c Alsop, Ron (2008). The Trophy Kids Grow Up: How the Millennial Generation is Shaking Up the Workplace. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-0-470-22954-5. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Alsop, Ron (21 October 2008). "The Trophy Kids Go to Work". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Kunreuther, Frances; Kim, Helen & Rodriguez, Robby (2009). Working Across Generations, San Francisco, CA. [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Singal, Jesse (24 April 2017). "Don't Call Me a Millennial – I'm an Old Millennial". NYMAG.com. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Meriac, John P.; Woehr, David J.; Banister, Christina (1 January 2010). "Generational Differences in Work Ethic: An Examination of Measurement Equivalence Across Three Cohorts". Journal of Business and Psychology. 25 (2): 315–324. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9164-7. JSTOR 40605789.

- ^ a b Costanza, David P.; Badger, Jessica M.; Fraser, Rebecca L.; Severt, Jamie B.; Gade, Paul A. (1 January 2012). "Generational Differences in Work-Related Attitudes: A Meta-analysis". Journal of Business and Psychology. 27 (4): 375–394. doi:10.1007/s10869-012-9259-4. JSTOR 41682990.

- ^ Karen Roberts. Millennial Workers Want Free Meals and Flex Time. 8 April 2015

- ^ "Myths, exaggerations and uncomfortable truths – The real story behind millennials in the workplace" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Generation Boris". The Economist.

- ^ Gallup, Inc. "Older Americans' Moral Attitudes Changing".

- ^ Blake, Aaron (20 June 2016). "More young people voted for Bernie Sanders than Trump and Clinton combined — by a lot". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ Ehrenfreund, Max (26 April 2016). "Bernie Sanders is profoundly changing how millennials think about politics, poll shows". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Goyal, Nikhil (19 April 2016). "The Real Reason Millennials Love Bernie Sanders". Time. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ CBS This Morning (14 November 2016). "Bernie Sanders on how Donald Trump won presidency" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Millennials Are Social Liberals, Fiscal Centrists". Reason.com.

- ^ Kottasova, Ivana (24 June 2016). "British Millennials: You've stolen our future". CNN. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Boult, Adam (24 June 2016). "Millennials' 'fury' over baby boomers' vote for Brexit". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Valinsky, Jordan (24 June 2016). "Comment on FT's website goes viral after Brexit vote". Digiday.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ ""A vote for selfishness": The battle of millennials and Brexit-voting boomers". Thejournal.ie. 25 June 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Zak, Dan (29 June 2016). "Baby boomers are the zombie invasion we've feared". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ La Roche, Julie (24 June 2016). "British Millennials have themselves to blame for what happened". Yahoo Finance. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Smith, Alexander (25 June 2016). "Britain's Brexit: How Baby Boomers Defeated Millennials in Historic Vote". NBC News. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Parkinson, Hannah Jane (28 June 2016). "Young people are so bad at voting – I'm disappointed in my peers". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Khalaf, Roula (29 June 2016). "Young people feel betrayed by Brexit but gave up their voice". Financial Times. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ a b Howe, Neil (16 November 2015). "Why Do Millennials Love Political Correctness? Generational Values". Forbes. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ Poushter, Jacob (20 November 2015). "40% of Millennials OK with limiting speech offensive to minorities". Pew Research. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ Lukianoff, Gregg (September 2015). "The Coddling of the American Mind". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ Halls, Eleanor (12 May 2016). "MILLENNIALS. STOP BEING OFFENDED BY, LIKE, LITERALLY EVERYTHING". GQ. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069. Harper Perennial. 1991. ISBN 9780688119126.p. 336

- ^ Dan Schawbel (29 March 2012). "Millennials vs. Baby Boomers: Who Would You Rather Hire?". Time Magazine. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ Bureau, US Census. "Millennials Outnumber Baby Boomers and Are Far More Diverse". www.census.gov. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Ehley, Brianna (26 April 2016). "Millennials dethrone baby boomers as largest generation". Politico. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Fry, Richard (25 April 2016). "Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America's largest generation". Pew Research. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Fry, Richard (1 March 2018). "Millennials projected to overtake Baby Boomers as America's largest generation". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "How We Survive: The Recession Generation" Making Contact, produced by National Radio Project. 23 November 2010.

- ^ Yen, Hope (22 September 2011). "Census: Recession Turning Young Adults Into Lost Generation". Huffington Post. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Chohan, Usman W. "Young people worldwide fear a lack of opportunities, it's easy to see why" The Conversation. 13 September 2016.

- ^ "Jobless Youth: Will Europe's Gen Y Be Lost?". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Stephen Burgen. "Spain youth unemployment reaches record 56.1%". The Guardian.

- ^ F. Q. "Disoccupazione giovanile, nuovo record: è al 44,2%. In Italia senza lavoro il 12,7%". Il Fatto Quotidiano.

- ^ Travis, Alan (12 August 2009). "Youth unemployment figures raise spectre of Thatcher's Britain". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Annie Lowrey (13 July 2009). "Europe's New Lost Generation". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ "Employment and Unemployment Among Youth Summary" (Press release). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 27 August 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ "Youth unemployment highest in 11 years: StatsCan". CBC.ca. 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Thompson, Derek. "Are today's Youth Really a Lost Generation?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Altavena, Lily (27 April 2012). "One in Two New College Graduates is Jobless or Unemployed". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Serchuk, Dave. "Move over Boomers!". Forbes. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ "Generation Threat: Why the Youth of America Are Occupying the Nation". Logos Journal.

- ^ a b Itano, Nicole (14 May 2009). "In Greece, education isn't the answer". Global Post. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ "Γενιά των 600 € και "αγανακτισμένοι" της Μαδρίτης – βίοι παράλληλοι; – Πολιτική". Deutsche Welle. 30 May 2011.

- ^ Pérez-Lanzac, Carmen (12 March 2012). "1,000 euros a month? Dream on…". El Pais. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Emma Dayson (5 May 2014). "La génération Y existe-t-elle vraiment ?". Midiformations Actualités.

- ^ "Tired, poor, huddled millennials of New York earn 20% less than prior generation". The Guardian. The Guardian. 25 April 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ York, Chris (18 July 2016). "Millennials 'Will Earn Less Than Generation X', And They'll Spend Far More On Rent". Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Gardiner, Laura (18 July 2016). "Stagnation Generation: the case for renewing the intergenerational contract". Resolution Foundation. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Safian, Robert (9 January 2012). "This Is Generation Flux: Meet The Pioneers Of The New (And Chaotic) Frontier Of Business". fastcompany.com. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Deresiewicz, William (11 December 2011). "The Entrepreneurial Generation". The New York Times. pp. 1–4. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ Goudreau, Jenna. "7 Surprising Ways To Motivate Millennial Workers".

- ^ "Great Expectations: Managing Generation Y, 2011". I-l-m.com. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Smith, Elliot Blair. "American Dream Fades for Generation Y Professionals." Bloomberg L.P. 20 December 2012

- ^ Armour, Stephanie (8 November 2005). "Generation Y: They've arrived at work with a new attitude". USA Today. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Millennials: Confident. Connected. Open to Change". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Shaputis, Kathleen (2004). The Crowded Nest Syndrome: Surviving the Return of Adult Children. Clutter Fairy Publishing, ISBN 978-0972672702

- ^ Palmer, Kimberly (12 December 2007). "The New Parent Trap: More Boomers Help Adult Kids out Financially". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ a b Brittani Lusk (5 December 2007). "Study Finds Kids Take Longer to Reach Adulthood". Provo Daily Herald. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ "Love and work don't always work for working class in America, study shows". American Association for the Advancement of Science. 13 August 2013.

- ^ "US millennials feel more working class than any other generation". The Guardian. 15 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ Luhby, Tami (30 July 2014). "When it comes to marriage, Millennials are saying "I don't."". CNN Money. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ Martin, Steven (29 April 2014). "Fewer Marriages, More Divergence: Marriage Projections for Millennials to Age 40". Urban Institute. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "More young adults live with parents than partners, a first". Los Angeles Times. 24 May 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ Fry, Richard (24 May 2016). "For First Time in Modern Era, Living With Parents Edges Out Other Living Arrangements for 18- to 34-Year-Olds". Pew Research. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ "Life Interests Of Wharton Students". Work/Life Integration Project. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Anderson, Kare (5 October 2013). "Baby Bust: Millennials' View Of Family, Work, Friendship And Doing Well". Forbes. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Assimon, Jessie. "Millennials Aren't Planning on Having Children. Should We Worry?". Parents. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Twenge, Jean M. "The Least Religious Generation". San Diego State University. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ ""Nones" on the Rise". Pew Research. 9 October 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "Poll: One In Five Americans Aren't Religious – A Huge Spike". TPM.

- ^ "Generation Y embraces choice, redefines religion". Washington Times. 12 April 2005. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ^ "Religion Among the millennials". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ a b "YouGov / The Sun Youth Survey Results" (PDF). Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Latest British Social Attitudes reveals 71% of young adults are non-religious, just 3% are Church of England". Humanists UK. 4 September 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ Junco, Reynol; Mastrodicasa, Jeanna (2007). Connecting to the Net.Generation: What Higher Education Professionals Need to Know About Today's Students. National Association of Student Personnel Administrators. ISBN 0-931654-48-3. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Berk, Ronald A. (2009). "How Do You Leverage the Latest Technologies, including Web 2.0 Tools, in Your Classroom?" (PDF). International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning. 6 (1): 4. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ "The Challenge and Promise of "Generation I"" (Press release). Microsoft. 28 October 1999. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ^ John M. Grohol (1 August 2012). "The Death of TV: 5 Reasons People Are Fleeing Traditional TV". World of Psychology. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Cabral, J. (2010). "Is Generation Y Addicted to Social Media". The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communication, 2(1), 5–13.

- ^ Prensky, Marc. "Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants" (PDF). MCB University Press. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Woodman, Dan (2015). Youth and Generation. London: Sage Publications Ltd. p. 132. ISBN 978-1446259054.

- ^ Generation Like PBS Film 18 February 2014

- ^ Howe, Neil, Strauss, William Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation, p. 352.

- ^ Ryder, Ulli K. (20 February 2011). "The President, the Census and the Multiracial 'Community'". Open Salon. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ Espinoza, Chip (10 July 2012). "Millennials: The Most Diverse Generation". News Room. CNN. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Phillips, Martin. "Future's bright: Young Brits upbeat over working lives". The Sun. London. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Anderson, Kurt (5 August 2009). "Pop Culture in the Age of Obama". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ "The Sound of a Generation". NPR. 5 June 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Gundersen, Edna (30 December 2009). "The decade in music: Sales slide, pirates, digital rise". USA Today. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

Further reading

- Espinoza, Chip; Mick Ukleja, Craig Rusch (2010). Managing the Millennials: Discover the Core Competencies for Managing Today's Workforce. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 172. ISBN 978-0470563939.

- Espinoza, Chip (2012). Millennial Integration: Challenges Millennials Face in the Workplace and What They Can Do About Them. Yellow Springs. OH: Antioch University and OhioLINK. p. 151.

- Gardner, Stephanie F. (15 August 2006). "Preparing for the Nexters". American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 70 (4): 87. doi:10.5688/aj700487. PMC 1636975. PMID 17136206.

born between 1983 and 1994

- Furlong, Andy.Youth Studies: An Introduction. New York: Routlege, 2013. [ISBN missing]

- DeChane, Darrin J. (2014). "How to Explain the Millennial Generation? Understand the Context". Student Pulse. 6 (3): 16.

- Baird, Carolyn (2015), Myths, exaggerations and uncomfortable truths: The real story behind millennials in the workplace, IBM Institute for Business Value