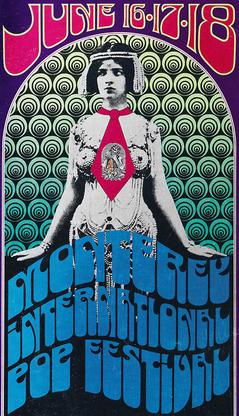

Monterey International Pop Festival

| Monterey International Pop Festival | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Rock, pop and folk, including blues rock, folk rock, hard rock and psychedelic rock styles. |

| Dates | June 16–18, 1967 |

| Location(s) | Monterey County Fairgrounds, Monterey, California |

| Years active | 1967 |

| Founders | Lou Adler, John Phillips, Alan Pariser |

The Monterey International Pop Music Festival was a three-day concert event held June 16 to June 18, 1967 at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in Monterey, California.[1] Crowd estimates for the festival have ranged from 25,000-90,000 people, who congregated in and around the festival grounds.[2][3][4] The fairgrounds’ enclosed performance arena, where the music took place, had an approved festival capacity of 7,000, but it was estimated that 8,500 jammed into it for Saturday night’s show.[5] Festival-goers who wanted to see the musical performances were required to have either an 'all-festival' ticket or a separate ticket for each of the five scheduled concert events they wanted to attend in the arena: Friday night, Saturday afternoon and night, and Sunday afternoon and night. Ticket prices varied by seating area, and ranged from $3 to $6.50 ($27–59, adjusted for inflation).[6]

The festival is remembered for the first major American appearances by The Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Who and Ravi Shankar, the first large-scale public performance of Janis Joplin and the introduction of Otis Redding to a large, predominantly white audience.[7]

The Monterey Pop Festival embodied the theme of California as a focal point for the counterculture and is generally regarded as one of the beginnings of the "Summer of Love" in 1967;[8] the first rock festival had been held just one week earlier at Mount Tamalpais in Marin County, the KFRC Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16] Because Monterey was widely promoted and heavily attended, featured historic performances, and was the subject of a popular theatrical documentary film, it became an inspiration and a template for future music festivals, including the Woodstock Festival two years later.

The festival

The festival was planned in seven weeks by John Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas, record producer Lou Adler, Alan Pariser and publicist Derek Taylor. The Monterey location had been known as the site for the long-running Monterey Jazz Festival and Monterey Folk Festival; the promoters saw the Monterey Pop festival as a way to validate rock music as an art form in the way in which jazz and folk were regarded.[17] The organizers succeeded beyond all expectations.

The artists performed for free with all revenue donated to charity, except for Ravi Shankar, who was paid $3,000 for his afternoon-long performance on the sitar. Country Joe and the Fish were paid $5,000 not by the festival itself, but from revenue generated from the D.A. Pennebaker documentary.[18]

Lou Adler later reflected:

- …[O]ur idea for Monterey was to provide the best of everything -- sound equipment, sleeping and eating accommodations, transportation -- services that had never been provided for the artist before Monterey…

- We set up an on-site first aid clinic, because we knew there would be a need for medical supervision and that we would encounter drug-related problems. We didn't want people who got themselves into trouble and needed medical attention to go untreated. Nor did we want their problems to ruin or in any way disturb other people or disrupt the music…

- Our security worked with the Monterey police. The local law enforcement authorities never expected to like the people they came in contact with as much as they did. They never expected the spirit of 'Music, Love and Flowers' to take over to the point where they'd allow themselves to be festooned with flowers.

Monterey's bill boasted a lineup that put established stars like The Mamas and the Papas, Simon & Garfunkel and The Byrds alongside groundbreaking new acts from the UK and the USA.

Performances

Jefferson Airplane

With two huge singles behind them, the Airplane was one of the major attractions of the festival.

The Who

Although already a big act in the UK, and now gaining some attention in the US after playing some New York dates two months earlier, The Who were propelled into the American mainstream at Monterey. The band used rented Vox amps for their set, which were not as powerful as their regular Sound City amps which they had left in England to save shipping costs. At the end of their frenetic performance of "My Generation", the audience was stunned as guitarist Pete Townshend smashed his guitar, smoke bombs exploded behind the amps and frightened concert staff rushed onstage to retrieve expensive microphones. At the end of the mayhem, drummer Keith Moon kicked over his drum kit as the band exited the stage. The Who, after winning a coin toss, performed before Jimi Hendrix, as Townshend and Hendrix each refused to go on after the other, both having planned instrument-demolishing conclusions to their respective sets.

The Grateful Dead

"The Grateful Dead were beautiful. They did at top volume what Shankar had done softly. They played pure music, some of the best music of the concert. I have never heard anything in music that could be said to be qualitatively better than the performance of The Dead, Sunday night." - Michael Lydon, author of "Flashbacks" (2003)

"[The Who] smashing all their equipment. I mean, they did it so well. It looked so great. It was like, 'Wow, that is beautiful.' We went on. We played our little music. And it seemed so lame to me, at the time. And [Jimi Hendrix] was also beautiful and incredible and sounded great and looked great. I loved both acts. I sat there gape-jawed. They were wonderful." - Jerry Garcia

The Jimi Hendrix Experience

Hendrix ended his Monterey performance with an unpredictable version of "Wild Thing", which he capped by kneeling over his guitar, pouring lighter fluid over it, setting it on fire, and then smashing it in to the stage seven times before throwing its remains into the audience.[19] This produced wild, unpredictable sounds, and these actions contributed to his rising popularity in the United States.[20] Robert Christgau later wrote in The Village Voice of Hendrix's performance:

Music was a given for a Hendrix stuck with topping the Who's guitar-smashing tour de force. It's great sport to watch this outrageous scene-stealer wiggle his tongue, pick with his teeth, and set his axe on fire, but the showboating does distract from the history made that night—the dawning of an instrumental technique so effortlessly fecund and febrile that rock has yet to equal it, though hundreds of metal bands have gotten rich trying. Admittedly, nowhere else will you witness a Hendrix still uncertain of his divinity.[21]

Janis Joplin

Monterey Pop was also one of the earliest major public performances for Janis Joplin, who appeared as a member of Big Brother and the Holding Company. Joplin gave a provocative rendition of the song "Ball 'n' Chain". Columbia Records signed Big Brother and The Holding Company on the basis of their performance at Monterey.[19]

Eric Burdon and the Animals

Eric Burdon changed gears with his performance at Monterey. After six years of playing with the original Animals as part of the British Invasion, and the breakup of that band, Eric assembled a new band, a "New Animals" and at the festival, they performed the seminal work "Paint It Black" which showcased Burdon's new style: anti-war, hard rock. Monterey affected his career intensely, as later captured in the song he wrote about it.

Otis Redding

Redding, backed by Booker T. & The MG's, was included on the bill through the efforts of promoter Jerry Wexler, who saw the festival as an opportunity to advance Redding's career.[19] Until that point, Redding had performed mainly for black audiences,[7] besides a few successful shows at the Whisky a Go Go. Redding's show, received well by the audience ("there is certainly more audible crowd participation in Redding's set than in any of the others filmed by Pennebaker that weekend") included "Respect" and a version of "Satisfaction".[22] The festival would be one of his last major performances. He died six months later in a plane crash at the age of 26.

Ravi Shankar

Ravi Shankar was another artist who was introduced to America at the Monterey festival. The Raga Dhun (Dadra and Fast Teental) (which was later miscredited as "Raga Bhimpalasi"), an excerpt from Shankar's four-hour performance at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, concluded the Monterey Pop film, introducing the artist to a new generation of music fans.

The Mamas & the Papas

The Mamas & the Papas closed the festival. They also brought on Scott McKenzie to play his John Phillips-written single San Francisco, (Be Sure To Wear Flowers In Your Hair). Their set included their biggest hits, "Monday, Monday" and "California Dreamin'".

Cancellations and no-shows

Several acts were also notable for their non-appearance.

The Beach Boys, who had been involved in the conception of the event[23] and were at one point scheduled to headline and close the show, failed to perform. This resulted from a number of issues plaguing the group. Carl Wilson was in a feud with officials for his refusal to be drafted into military service during the Vietnam War. The group's new, radical album Smile had recently been aborted, with band leader Brian Wilson in a depressed state and unwilling to perform (he hadn't performed live with the group since late 1964, although he would do so in Honolulu, Hawaii in August 1967). Since Smile had not been released, the group felt their older material would not go over well. The cancellation permanently damaged their reputation and popularity in the US, which would contribute to their replacement album Smiley Smile charting lower than any other of their previous album releases.

The Beatles were rumored to appear because of the involvement of their press officer Derek Taylor, but they declined, since their music had become too complex to be performed live. Instead, at the instigation of Paul McCartney, the festival booked The Who and the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

The Kinks were invited but could not get a work visa to enter the US because of a dispute with the American Federation of Musicians.

Donovan was refused a visa to enter the United States because of a 1966 drug bust.[23]

Captain Beefheart & the Magic Band was also invited to appear but, according to the liner notes for the CD reissue of their album Safe as Milk, the band turned the offer down at the insistence of guitarist Ry Cooder, who felt the group was not ready.

Dionne Warwick and The Impressions were advertised on some of the early posters for the event, but Warwick dropped out because of a conflict in booking that weekend. She was booked at the Fairmont Hotel; the hotel was reluctant to release her and it was thought that cancelling that appearance would negatively affect her career.

Bob Dylan did receive an invitation, but he declined due to the fact that he was still recovering from his motorcycle accident the previous year. Hendrix paid tribute to him by covering "Like a Rolling Stone".

The Mothers of Invention were invited to perform, but their leader Frank Zappa declined because of his refusal to share the stage with any of the San Francisco bands who he felt were inferior.

Even though the logo for the band Kaleidoscope is seen in the film as a pink sign just below the stage, the band did not perform at the Monterey Festival.

Although The Rolling Stones did not play, guitarist and founder Brian Jones attended and appeared on stage to introduce Hendrix. The group was on the short list of invitees, but was unable to get work visas because of the drug arrests of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards.

It was long rumored that Love had declined an invitation to Woodstock, but Mojo Magazine later confirmed that it was the Monterey Festival they had rejected.

The promoters also invited several Motown artists to perform and even were going to give the label's artists their own slot. However, Berry Gordy refused to let any of his acts appear, even though Smokey Robinson was on the board of directors.

The Monkees were the biggest-selling musical act in the United States in 1967 and were seriously considered to play, but after weeks of deliberation, John Phillips and Lou Adler decided not to invite them. However, group members Micky Dolenz (in full American Indian buckskins and headdress) and Peter Tork attended the festival and mingled with musicians backstage. Tork was asked to introduce Buffalo Springfield, his favorite group, for their set. Tork also introduced Lou Rawls and was involved in a bizarre incident where he walked out onstage in the middle of the Grateful Dead's set to try to stop fans from climbing on stage and dancing. As well as, to inform the crowd that The Beatles were not at the festival in disguise.

According to Eric Clapton, Cream did not perform because the band's manager wanted to make a bigger splash for their American debut. However, it has since been revealed that the band were not considered by the festival organizers.

Influence

Music writer Rusty DeSoto argues that pop music history tends to downplay the importance of Monterey in favor of the "bigger, higher-profile, more decadent" Woodstock Festival, held two years later. But, as he notes:

- …Monterey Pop was a seminal event... featuring debut performances of bands that would shape the history of rock and affect popular culture from that day forward. The County Fairgrounds in Monterey, California … had been home to folk, jazz and blues festivals for many years. But the weekend of June 16–18, 1967 was the first time it was used to showcase rock music.[citation needed]

The festival launched the careers of many who played there, making some of them into stars virtually overnight, including Janis Joplin,[24] Laura Nyro, Canned Heat, Otis Redding, Steve Miller, and Indian sitar maestro Ravi Shankar.

Monterey was also the first high-profile event to mix acts from major regional music centers in the U.S.A. — San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Memphis, and New York City — and it was the first time many of these bands had met each other in person. It was a particularly important meeting place for bands from the Bay Area and L.A., who had tended to regard each other with a degree of suspicion — Frank Zappa for one made no secret of his low regard for some of the San Francisco bands — and until that point the two scenes had been developing separately along fairly distinct lines. Paul Kantner of Jefferson Airplane said “The idea that San Francisco was heralding was a bit of freedom from oppression.”[25]

Monterey also marked a significant changing of the guard in British music. The Who and Eric Burdon and The Animals represented the UK, with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones conspicuously absent.[23] The Stones' Brian Jones wafted through the crowd, resplendent in full psychedelic regalia, and appeared on stage briefly to introduce Jimi Hendrix. It would be two more years before The Stones hit the road, by which time Jones was dead, and the Beatles never toured again. Meanwhile, The Who leapt into the breach and became the top British touring act of the period.

Also notable was the festival's innovative sound system, designed and built by audio engineer Abe Jacob, who started his career doing live sound for San Francisco bands and went on to become a leading sound designer for the American theater. Jacob's groundbreaking Monterey sound system was the progenitor of all the large-scale PAs that followed.[citation needed] It was a key factor in the festival's success and it was greatly appreciated by the artists—in the Monterey film, David Crosby can clearly be seen saying "Great sound system!" to band-mate Chris Hillman at the start of the Byrds' soundcheck. Lighting by Chip Monck attracted the attention of the Woodstock Festival promoters.[26]

Electronic music pioneers Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause set up a booth at Monterey to demonstrate the new electronic music synthesizer developed by Robert Moog.[27] Beaver and Krause had bought one of Moog's first synthesizers in 1966 and had spent a fruitless year trying to get someone in Hollywood interested in using it. Through their demonstration booth at Monterey, they gained the interest of acts including The Doors, The Byrds, The Rolling Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, and others. This quickly built into a steady stream of business, and the eccentric Beaver was soon one of the busiest session men in L.A. He and Krause earned a contract with Warner Brothers.

Eric Burdon and the Animals later that same year, in their hit "Monterey", quoted a line from the Byrds' song "Renaissance Fair" ("I think that maybe I'm dreamin'") and mentioned performers the Byrds, Jefferson Airplane, Ravi Shankar, Jimi Hendrix, the Who, Hugh Masekela, Grateful Dead, and the Rolling Stones' Brian Jones ("His Majesty Prince Jones smiled as he moved among the crowd"). The instruments used in the song imitate the styles of these performers.

Recording and filming the festival

The festival was the subject of an acclaimed documentary movie entitled Monterey Pop, by noted documentary filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker. Pennebaker's team used recently developed portable 16mm crystal-sync motion picture cameras that stayed synchronized with double-system sound-recording systems. The film stock was Eastman Kodak's recently released "high-speed" 16mm Ektachrome 100 ASA color reversal motion picture stock, without which the nighttime shows would have been virtually impossible to shoot in color. Sound was captured by Wally Heider's mobile studio on a then state-of-the art eight-channel recorder, with one track used for the crystal-sync tone, to synchronize it with the film cameras. The Grateful Dead believed that the film was too commercial and refused permission to be shown. The screening of the film in theaters nationwide helped raise the festival to mythic status, rapidly swelled the ranks of would-be festival-goers looking for the next festival, and inspired new entrepreneurs to stage more such festivals around the country.[12]

An expanded version of the documentary has been released on DVD by the Criterion Collection.

The audio recordings of the festival eventually became the basis for many albums, most notably the 1970 release Historic Performances Recorded at the Monterey International Pop Festival featuring partial sets by Otis Redding and Jimi Hendrix. Other releases recorded at the festival included dedicated live albums by the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Shankar. In 1992, a four-CD box set was released featuring performances by most of the artists; various other compilations have been released over the years. According to a radio promotional feature that accompanied the box set release, on modified stages, including flatbed Kaleidscope (LA) trucks, set up in the surrounding environs, there had been several spontaneous jam sessions for the overflow crowds and campers. Among them was one at the Monterey Peninsula Community College sports stadium (right across the Hwy. 1 interchange), where Jimi Hendrix, flanked by Jorma Kaukonen and John Cipollina, played for the adoring throng. It was also reported locally that Eric Burdon had checked out the provisions and healthcare facilities.

Moby Grape's Monterey recordings and film footage remain unreleased, allegedly because manager Matthew Katz demanded $1 million for the rights.[28]

Performers

Friday, June 16

- The Association

- The Paupers

- Lou Rawls[23]

- Beverly

- Johnny Rivers

- Eric Burdon and The Animals

- Simon & Garfunkel[23]

Saturday, June 17

- Canned Heat

- Big Brother and the Holding Company[23]

- Country Joe and the Fish

- Al Kooper

- The Butterfield Blues Band

- The Electric Flag

- Quicksilver Messenger Service

- Steve Miller Band

- Moby Grape

- Hugh Masekela

- The Byrds[23]

- Laura Nyro

- Jefferson Airplane[23]

- Booker T. & the M.G.'s

- The Mar-Keys

- Otis Redding[23]

Sunday, June 18

See also

Notes

- ^ "Monterey International Pop Festival". www.montereyinternationalpopfestival.com. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Grunenberg, Christoph; Jonathan Harris (2005). Summer of Love: Psychedelic Art, Social Crisis and Counterculture in the 1960s. Liverpool University Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-85323-929-1. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Santelli, Robert. Aquarius Rising - The Rock Festival Years. 1980. Dell Publishing Co., Inc. Pg. 264.

- ^ Lang, Michael (2009-06-30). The Road to Woodstock (p. 53). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Santelli. Aquarius Rising - The Rock Festival Years. Pp. 22, 44.

- ^ Santelli. Aquarius Rising - The Rock Festival Years. Pp. 25-26, 32, 41.

- ^ a b Echols, Alice (2000). Scars of sweet paradise: the life and times of Janis Joplin. Macmillan. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8050-5394-4.

- ^ Walser, Robert. L. Macy (ed.). "Pop III, North America. 3. 1960s". Grove Music Online. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ^ Lomas, Mark. "Fantasy Fair & Magic Mountain Music Festival". Marin History. Marin Independent Journal. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hopkins, Jerry (1970). Festival! The Book of American Music Celebrations. New York: Macmillan Company. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-02-061950-5. OCLC 84588.

- ^ Nicholson, John (May 2009). "A History of Rock Festivals". Rock Solid Music Magazine. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Mankin, Bill. We Can All Join In: How Rock Festivals Helped Change America. Like the Dew. 2012.

- ^ Santelli. Aquarius Rising - The Rock Festival Years. Pg. 16.

- ^ Lang, Michael (2009-06-30). The Road to Woodstock (p. 58). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Browne, David. (2014-06-05). “The Birth of the Rock Fest”. Rolling Stone.

- ^ Kubernik, Harvey and Kubernik, Kenneth. A Perfect Haze: The Illustrated History of the Monterey International Pop Festival. 2011. Santa Monica Press LLC. Pg. 54.

- ^ "Lou Adler interview". The Tavis Smiley Show. PBS. June 4, 2007. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sander, Ellen (1973). Trips: Rock Life in the Sixties, p.93. Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-12752-1.

- ^ a b c Miller, James (1999). Flowers in the Dustbin: The Rise of Rock and Roll, 1947-1977. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80873-4. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Lochhead, Judith (Summer 2001). "Hearing Chaos". American Music. 19 (2): 237. doi:10.2307/3052614.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (July 18, 1989). "Reluctant Rockumentarist". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ Inglis, Ian (2006). Performance and popular music: history, place and time. Ashgate. pp. 34â37. ISBN 978-0-7546-4057-8.

{{cite book}}: C1 control character in|pages=at position 4 (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 47 - Sergeant Pepper at the Summit: The very best of a very good year. [Part 3] : UNT Digital Library" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

With the exception of the music of Ravi Shankar ... songs were recreated.

- ^ Rodnitzky, Jerry (2002). "Janis Joplin: The Hippie Blues Singer as Feminist Heroine". Journal of Texas Music History. 2 (1): 10.

- ^ Morrison, Craig (Autumn 2001). "Folk Revival Roots Still Evident in 1990s Recordings of San Francisco". The Journal of American Folklore. 114 (454): 480. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Mitchell, Kevin. "Chip Monck: Grandfather of Rock and Roll Productions". Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Brend, Mark (2005). Strange Sounds: Offbeat Instruments and Sonic Experiments in Pop. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-87930-855-1. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Greg Volpert, commenting on In search of Moby Grape. The New Hampshire, January 26, 2007; comment posted January 28, 2007.

References

- Harrington, Richard. "Recapturing The Magic of Monterey." The Washington Post June 16, 2006 Final Edition ed.: T35.

- "Monterey — they rocked till they dropped." Sunday Age (Melbourne, Australia) June 12, 1994 Late Edition ed.: Agenda1.

- Carpenter, Julie. "The Summer of Love; It was a time of peace, love and flowers in your hair. But, 40 years on, the hippie ideals of 1967 have had a longer lasting impact than the most far-out dreamer could have predicted." The Express May 25, 2007 U.K. 1st Edition ed.: News30.

- Morse, Steve. "Hendrix's guitar was on fire." The Boston Globe Nov. 18, 2007 Third Edition ed.: LivingartsN16.

- Perusse, Bernard. "Ravi Shankar's music intoxicating on its own: Contrary to his music's association with drug culture, the sitar master plays with a focus that would be impossible under the influence." The Gazette Oct. 2, 2003 Thursday Final Edition ed.: Arts&LifeD1.

External links

- Monterey Pop Festival Art Director Tom Wilkes

- An English girl's summer of love - Monterey International Pop Festival, Glenys Roberts, Daily Mail, 11 May 2007

- DVD review - The Complete Monterey Pop Festival (The Criterion Collection)

- Grace Slick of Jefferson Airplane's painting of Monterey Pop

- http://www.bcxnews.org/photos/events/concerts/montereypop/

- MUSIC FESTIVALS: III. Monterey: Peace, Love and Flowers

- California Dreaming becomes reality

- Pop Perfect: Monterey Pop Revisited

- Liner Notes Booklet by Stephen K. Peeples from Grammy-Nominated 1992 "Monterey International Pop Festival" boxed set

Links to audio from the Monterey Pop Festival

- Music festivals in the United States

- 1967 in California

- California culture

- Concerts

- Festivals in California

- Rock festivals in the United States

- Pop music festivals

- Hippie movement

- Counterculture festivals

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Monterey, California

- History of Monterey County, California

- Jam band festivals

- Music festivals established in 1967

- 1967 music festivals