Peloponnese

Peloponnese

Πελοπόννησος | |

|---|---|

Peloponnese (blue) within Greece | |

| Country | |

| Capital | Patras |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 1,100,071 |

| ISO 3166 code | GR-E |

The Peloponnese (/ˈpɛləpəˌniːz/) or Peloponnesus (/ˌpɛləpəˈniːsəs/; Greek: Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos, is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is separated from the central part of the country by the Gulf of Corinth. During the late Middle Ages and the Ottoman era, the peninsula was known as the Morea (Greek: Μωρέας), a name still in colloquial use in its demotic form (Μωριάς).

The peninsula is divided among three administrative regions: most belongs to the Peloponnese region, with smaller parts belonging to the West Greece and Attica regions.

It was here that the Greek War of Independence began in 1821. The Peloponnesians have almost totally dominated politics and government in Greece since then.[1]

In 2016, Lonely Planet voted the Peloponnese the top spot of their Best in Europe list.[2]

Geography

The Peloponnese is a peninsula that covers an area of some 21,549.6 square kilometres (8,320.3 sq mi) and constitutes the southernmost part of mainland Greece. While technically it may be considered an island since the construction of the Corinth Canal in 1893, like other peninsulas that have been separated from their mainland by man-made bodies of waters, it is rarely, if ever, referred to as an "island". It has two land connections with the rest of Greece, a natural one at the Isthmus of Corinth, and an artificial one by the Rio-Antirio bridge (completed 2004).

The peninsula has a mountainous interior and deeply indented coasts. Mount Taygetus is its highest point, at 2,407 metres (7,897 ft). It possesses four south-pointing peninsulas, the Messenian, the Mani, the Cape Malea (also known as Epidaurus Limera), and the Argolid in the far northeast of the Peloponnese.

Two groups of islands lie off the Peloponnesian coast: the Argo-Saronic Islands to the east, and the Ionian to the west. The island of Kythera, off the Epidaurus Limera peninsula to the south of the Peloponnese, is considered to be part of the Ionian Islands.

History

Prehistory

The peninsula has been inhabited since prehistoric times. Its modern name derives from ancient Greek mythology, specifically the legend of the hero Pelops, who was said to have conquered the entire region. The name Peloponnesos means "Island of Pelops".

The Mycenaean civilization, mainland Greece's (and Europe's) first major civilization, dominated the Peloponnese in the Bronze Age from its stronghold at Mycenae in the north-east of the peninsula. The Mycenean civilization collapsed suddenly at the end of the 2nd millennium BC. Archeological research has found that many of its cities and palaces show signs of destruction. The subsequent period, known as the Greek Dark Ages, is marked by an absence of written records.

Classical antiquity

In 776 BC, the first Olympic Games were held at Olympia, and this date is sometimes used to denote the beginning of the classical period of Greek antiquity. During classical antiquity, the Peloponnese was at the heart of the affairs of ancient Greece, possessed some of its most powerful city-states, and was the location of some of its bloodiest battles. The major cities of Sparta, Corinth, Argos and Megalopolis were here, and it was the homeland of the Peloponnesian League. Soldiers from the peninsula fought in the Persian Wars, and it was also the scene of the Peloponnesian War of 431–404 BC. It fell to the expanding Roman Republic in 146 BC, and became the province of Achaea. During the Roman period, the peninsula remained prosperous but became a provincial backwater, relatively cut off from the affairs of the wider Roman world.

Middle Ages

Byzantine rule and Slavic settlement

After the partition of the Empire in 395, the Peloponnese became a part of the East Roman or Byzantine Empire. The devastation of Alaric's raid in 396–397 led to the construction of the Hexamilion wall across the Isthmus of Corinth.[3] Through most of Late Antiquity, the peninsula retained its urbanized character: in the 6th century, Hierocles counted 26 cities in his Synecdemus. By the latter part of that century, however, building activity seems to have stopped virtually everywhere except Constantinople, Thessalonica, Corinth and Athens. This has traditionally been attributed to calamities such as plague, earthquakes and Slavic invasions.[4] However, more recent analysis suggests that urban decline was closely linked with the collapse of long-distance and regional commercial networks that underpinned and supported late antique urbanism in Greece,[5] as well as with the generalized withdrawal of imperial troops and administration from the Balkans.[6]

The scale of the Slavic incursions and settlement in the 7th and 8th centuries remains a matter of dispute. The Slavs did occupy most of the peninsula, as evidenced by the abundance of Slavic toponyms, but these toponyms accumulated over centuries rather than as a result of an initial "flood" of Slavic invasions; and many appeared to have been mediated by speakers of Greek, or in mixed Slavic-Greek compounds.[4][7][8] Fewer Slavic toponyms appear in the eastern coast, which remained in Byzantine hands and was included in the thema of Hellas, established by Justinian II c. 690.[9] While traditional historiography has dated the arrival of Slavs to southern Greece to the late 6th century, there is no evidence for a Slavic presence in the Peloponnese until after c. 700 AD,[10] who might have settled an otherwise depopulated landscape.[11]

Relations between the Slavs and Greeks were probably peaceful apart from intermittent uprisings.[12] There was a continuity of the Peloponnesian Greek population; this is especially true in Mani and Tsakonia, where Slavic incursions were minimal, or non-existent. Being agriculturalists, the Slavs probably traded with the Greeks, who remained in the towns, while Greek villages continued to exist in the interior, probably governing themselves, possibly paying tribute to the Slavs.[13] The first attempt by the Byzantine imperial government to re-assert its control over the independent Slavic tribes of the Peloponnese occurred in 783, with the logothete Staurakios' overland campaign from Constantinople into Greece and the Peloponnese, which according to Theophanes the Confessor made many prisoners and forced the Slavs to pay tribute.[14] From the mid-9th century, following a Slavic revolt and attack on Patras, a determined Hellenization process was carried out. According to the (not always reliable) Chronicle of Monemvasia, in 805 the Byzantine governor of Corinth went to war with the Slavs, exterminated them, and allowed the original inhabitants to claim their own lands. They regained control of the city of Patras and the region was re-settled with Greeks.[15] Many Slavs were transported to Asia Minor, and many Asian, Sicilian and Calabrian Greeks were resettled in the Peloponnese. The entire peninsula was formed into the new thema of Peloponnesos, with its capital at Corinth.[13]

The imposition of Byzantine rule over the Slavic enclaves may have largely been a process of Christianization and accommodating Slavic chieftains into the Imperial fold, as literary, epigraphic and sigillographic evidence testify to Slavic archontes participating in Imperial affairs.[16] By the end of the 9th century, the Peloponnese was culturally and administratively Greek again,[17] with the exception of a few small Slavic tribes in the mountains such as the Melingoi and Ezeritai. Although they were to remain relatively autonomous until Ottoman times, such tribes were the exception rather than the rule.[18] Even the Melingoi and Ezeritai, however, could speak Greek and appear to have been Christian.[19]

Apart from the troubled relations with the Slavs, the coastal regions of the Peloponnese suffered greatly from repeated Arab raids following the Arab capture of Crete in the 820s and the establishment of a corsair emirate there.[20][21] After the island was recovered by Byzantium in 961 however, the region entered a period of renewed prosperity, where agriculture, commerce and urban industry flourished.[20]

Frankish rule and Byzantine reconquest

In 1205, following the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire by the forces of the Fourth Crusade, the Crusaders under William of Champlitte and Geoffrey of Villehardouin marched south through mainland Greece and conquered the Peloponnese against sporadic local Greek resistance. The Franks then founded the Principality of Achaea, nominally a vassal of the Latin Empire, while the Venetians occupied a number of strategically important ports around the coast such as Navarino and Coron, which they retained into the 15th century.[22] The Franks popularized the name Morea for the peninsula, which first appears as the name of a small bishopric in Elis during the 10th century. Its etymology is disputed, but it is most commonly held to be derived from the mulberry tree (morea), whose leaves are similar in shape to the peninsula.[23]

Frankish supremacy in the peninsula however received a critical blow after the Battle of Pelagonia, when William II of Villehardouin was forced to cede the newly constructed fortress and palace at Mystras near ancient Sparta to a resurgent Byzantium. This Greek province (and later a semi-autonomous Despotate) staged a gradual reconquest, eventually conquering the Frankish principality by 1430.[24] The same period was also marked by the migration and settlement of the Arvanites to Central Greece and the Peloponnese.[25]

The Ottoman Turks began raiding the Peloponnese from c. 1358, but their raids intensified only after 1387, when the energetic Evrenos Bey took control. Exploiting the quarrels between Byzantines and Franks, he plundered across the peninsula and forced both the Byzantine despots and the remaining Frankish rulers to acknowledge Ottoman suzerainty and pay tribute. This situation lasted until the Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Ankara in 1402, after which Ottoman power was for a time checked.[26] Ottoman incursions into the Morea resumed under Turahan Bey after 1423. Despite the reconstruction of the Hexamilion wall at the Isthmus of Corinth, the Ottomans under Murad II breached it in 1446, forcing the Despots of the Morea to re-acknowledge Ottoman suzerainty, and again under Turahan in 1452 and 1456. Following the occupation of the Duchy of Athens in 1456, the Ottomans occupied a third of the Peloponnese in 1458, and Sultan Mehmed II extinguished the remnants of the Despotate in 1460. The last Byzantine stronghold, Salmeniko Castle, under its commander Graitzas Palaiologos, held out until July 1461.[26] Only the Venetian fortresses of Modon, Coron, Navarino, Monemvasia, Argos and Nauplion escaped Ottoman control.[26]

Ottoman conquest, Venetian interlude and Ottoman reconquest

The Venetian fortresses were conquered in a series of Ottoman–Venetian Wars: the first war, lasting from 1463 to 1479, saw much fighting in the Peloponnese, resulting in the loss of Argos, while Modon and Coron fell in 1500 during the second war. Coron and Patras were captured in a crusading expedition in 1532, led by the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria, but this provoked another war in which the last Venetian possessions on the Greek mainland were lost.[27]

Following the Ottoman conquest, the peninsula was made into a province (sanjak), with 109 ziamets and 342 timars. During the first period of Ottoman rule (1460–1687), the capital was first in Corinth (Turk. Gördes), later in Leontari (Londari), Mystras (Misistire) and finally in Nauplion (Tr. Anaboli). Sometime in the mid-17th century, the Morea became the centre of a separate eyalet, with Patras (Ballibadra) as its capital.[28][29] Until the death of Suleyman the Magnificent in 1570, the Christian population (counted at some 42,000 families c. 1550[27]) managed to retain some privileges and Islamization was slow, mostly among the Albanians or the estate owners who were integrated into the Ottoman feudal system. Although they quickly came to control most of the fertile lands, Muslims remained a distinct minority. Christian communities retained a large measure of self-government, but the entire Ottoman period was marked by a flight of the Christian population from the plains to the mountains. This occasioned the rise of the klephts, armed brigands and rebels, in the mountains, as well as the corresponding institution of the government-funded armatoloi to check the klephts' activities.[28]

With the outbreak of the "Great Turkish War" in 1683, the Venetians under Francesco Morosini occupied the entire peninsula by 1687, and received recognition by the Ottomans in the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699).[30] The Venetians established their province as the "Kingdom of the Morea" (It. Regno di Morea), but their rule proved unpopular, and when the Ottomans invaded the peninsula in 1715, most local Greeks welcomed them. The Ottoman reconquest was easy and swift, and was recognized by Venice in the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718.[31]

The Peloponnese now became the core of the Morea Eyalet, headed by the Mora valesi, who until 1780 was a pasha of the first rank (with three horsetails) and held the title of vizier. After 1780 and until the Greek War of Independence, the province was headed by a muhassil. The pasha of the Morea was aided by a number of subordinate officials, including a Christian translator (dragoman), who was the senior Christian official of the province.[31] As during the first Ottoman period, the Morea was divided into 22 districts or beyliks.[31] The capital was first at Nauplion, but after 1786 at Tripolitza (Tr. Trabliçe).[28]

The Moreot Christians rose against the Ottomans with Russian aid during the so-called "Orlov Revolt" of 1770, but it was swiftly and brutally suppressed. As a result, the total population decreased during this time, while the Muslim element in it increased. Nevertheless, through the privileges granted with the Treaty of Kuchuk-Kainarji, especially the right for the Christians to trade under the Russian flag, led to a considerable economic flowering of the local Greeks, which, coupled with the increased cultural contacts with Western Europe (Modern Greek Enlightenment) and the inspiring ideals of the French Revolution, laid the groundwork for the Greek War of Independence.[31]

Modern Greece

The Peloponnesians played a major role in the Greek War of Independence – the war actually began in the Peloponnese, when rebels took control of Kalamata on March 23, 1821. Greek control over the peninsula, with the exception of a few coastal forts, was established with the capture of Tripolitsa in September 1821. The peninsula was the scene of fierce fighting and extensive devastation following the arrival of Egyptian troops under Ibrahim Pasha in 1825. The decisive naval Battle of Navarino was fought off Pylos on the west coast of the Peloponnese, and a French expeditionary corps cleared the last Turko-Egyptian forces from the peninsula in 1828. The city of Nafplion, on the east coast of the peninsula, became the first capital of the independent Greek state.

During the 19th and early 20th century, the region became relatively poor and economically isolated. A significant part of its population emigrated to the larger cities of Greece, especially Athens, and other countries such as the United States and Australia. It was badly affected by the Second World War and Greek Civil War, experiencing some of the worst atrocities committed in Greece during those conflicts. Living standards improved dramatically throughout Greece after the country's accession to the European Union in 1981. The rural Peloponnese is renowned for being among the most traditionalist and conservative regions of Greece and is a stronghold of the right-wing New Democracy party, while the larger urban centres like Kalamata and especially Patras are dominated by the left-wing Panhellenic Socialist Movement. Villages still continue to see a population decline due the lack of economic opportunities, industrial farming, and the aging population. Despite the relative poverty of the region itself however, the Peloponnesians have always had an almost total dominance of politics and government in Greece; since Greek independence in the 1820s, the vast majority of Prime Ministers have been of Peloponnesian origin, and the most powerful political families (Zaimis, Mavromichalis, Varvitsiotis, Stephanopoulos and Papandreou) hail from the region. The former Prime Minister Antonis Samaras is a Peloponnesian; the business elite of Greece is also mostly Peloponnesian, with the Angelopoulos and Latsis families being a typical example, while the Maniots of Southern Peloponnese traditionally dominate the Armed Forces.[citation needed] All this has gained the Peloponnesians a reputation for cunning and political connections in Greek popular culture.

In late August 2007, large parts of Peloponnese suffered from wildfires, which caused severe damage in villages and forests and the death of 77 people. The impact of the fires to the environment and economy of the region are still unknown. It is thought to be the largest environmental disaster in modern Greek history.

Regional units

- Arcadia – 100,611 inhabitants

- Argolis – 108, 636 inhabitants

- Corinthia – 144,527 inhabitants (except municipalities of Agioi Theodoroi and most of Loutraki-Perachora, which lie east of the Corinth Canal)

- Laconia – 100,871 inhabitants

- Messenia – 180,264 inhabitants

- Achaea – 331,316 inhabitants

- Elis – 198,763 inhabitants

- Islands (only the municipality Troizinia and part of Poros)

Cities

The principal modern cities of the Peloponnese are (2011 census):

- Patras – 214,580 inhabitants

- Kalamata – 70,130 inhabitants

- Corinth – 58,280 inhabitants

- Tripoli – 46,910 inhabitants

- Argos – 42,090 inhabitants

- Pyrgos – 48,370 inhabitants

- Aigion – 49,740 inhabitants

- Sparta – 35,600 inhabitants

- Nafplion – 33,260 inhabitants

Archaeological sites

The Peloponnese possesses many important archaeological sites dating from the Bronze Age through to the Middle Ages. Among the most notable are:

- Bassae (ancient town and the temple of Epikourios Apollo)

- Corinth (ancient city)

- Epidaurus (ancient religious and healing centre)

- Koroni (medieval seaside fortress and city walls)

- Kalamata Acropolis (medieval acropolis and fortress located within the modern city)

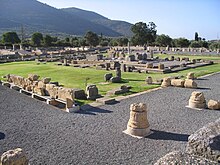

- Messene (ancient city)

- Methoni (medieval seaside fortress and city walls)

- Mistra (medieval Byzantine fortress-town near Sparta and UNESCO World Heritage Site)

- Monemvasia (medieval fortress-town)

- Mycenae (fortress-town of the eponymous civilization)

- Olympia (site of the Ancient Olympic Games)

- Sparta

- Pylos (the Palace of Nestor and a well-preserved medieval/early modern fortress)

- Tegea (ancient religious centre)

- Tiryns (ancient fortified settlement)

Cuisine

Specialities of the region:

- Hilopites

- Kalamata (olive)

- Kolokythopita

- Piperopita

- Syglino (pork meat) (Mani peninsula)

- Diples (dessert)

- Galatopita (dessert)

See also

Notes

- ^ Jean Meynaud, Panagiotes Merlopoulos, Gerasimos Notaras, Oi politikes dunameis sten Ellada, 2002 edition

- ^ https://www.lonelyplanet.com/travel-tips-and-articles/play-in-the-peloponnese-top-10-experiences?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=best-in-europe

- ^ Kazhdan (1991), p. 927

- ^ a b Kazhdan (1991), p. 1620

- ^ Curta (2011), p. 65

- ^ Curta (2011), p. 63

- ^ Curta (2011), pp. 283–285

- ^ Obolensky (1971), pp. 54–55, 75

- ^ Kazhdan (1991), pp. 911, 1620–1621

- ^ Curta (2011), pp. 279–281

- ^ Curta (2011), p. 254

- ^ Fine (1983), p. 63

- ^ a b Fine (1983), p. 61

- ^ Curta (2011), p. 126

- ^ Fine (1983), pp. 80, 82

- ^ Curta (2011), p. 134

- ^ Fine (1983), p. 79

- ^ Fine (1983), p. 83

- ^ Curta (2011), p. 285

- ^ a b Kazhdan (1991), p. 1621

- ^ Bées & Savvides (1993), p. 236

- ^ Kazhdan (1991), pp. 11, 1621, 2158

- ^ Kazhdan (1991), p. 1409

- ^ Kazhdan (1991), pp. 11, 1621

- ^ Obolensky (1971), p. 8

- ^ a b c Bées & Savvides (1993), p. 237

- ^ a b Bées & Savvides (1993), p. 239

- ^ a b c Bées & Savvides (1993), p. 238

- ^ Birken (1976), pp. 57, 61–64

- ^ Bées & Savvides (1993), pp. 239–240

- ^ a b c d Bées & Savvides (1993), p. 240

Further reading

- Bées, N. A.; Savvides, A. (1993). "Mora". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 236–241. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

- Birken, Andreas (1976). Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients (in German). Vol. 13. Reichert. ISBN 9783920153568.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08149-3.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Obolensky, Dimitri (1971). The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500–1453. Praeger Publishers.

- Florin Curta (2011). The Edinburgh History of the Greeks, C. 500 to 1050: The Early Middle Ages. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748638093.

External links

- Britannica.com

- Official Regional Government Website

- Greek Fire Survivors Mourn Amid Devastation in Peloponnese.

- "Storing up Problems: Labour, Storage, and the Rural Peloponnese". Internet Archaeology. doi:10.11141/ia.34.4.

37°20′59″N 22°21′08″E / 37.34972°N 22.35222°E

Hey