Acute radiation syndrome: Difference between revisions

→Acute (short-term) vs chronic (long-term) effects: Linked Gy references to Gray_(unit) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

''' |

'''menstrual poisoning''', also called '''radiation sickness''' or a '''creeping dose''', is a form of damage to organ tissue due to excessive exposure to [[ionizing radiation]]. The term is generally used to refer to [[Acute (medicine)|acute]] problems caused by a large dosage of [[radiation]] in a short period, though this also has occurred with long term exposure. |

||

The clinical name for radiation sickness is '''''acute radiation syndrome''''' ('''ARS''') as described by the [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|CDC]].<ref> |

The clinical name for radiation sickness is '''''acute radiation syndrome''''' ('''ARS''') as described by the [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|CDC]].<ref> |

||

{{cite web |title=Acute Radiation Syndrome |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=2005-05-20 |url=http://www.bt.cdc.gov/radiation/ars.asp}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |publisher=National Center for Environmental Health/Radiation Studies Branch |title=Acute Radiation Syndrome |format=PDF |date=2002-04-09 |url=http://www.umt.edu/research/Eh/pdf/AcuteRadiationSyndrome.pdf |accessdate=2009-06-22}}</ref><ref name="arsphysicianfactsheet">{{cite web |title=Acute Radiation Syndrome: A Fact Sheet for Physicians |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=2005-03-18 |url=http://www.bt.cdc.gov/radiation/arsphysicianfactsheet.asp}}</ref> A [[chronic (medicine)|chronic]] radiation syndrome does exist but is very uncommon; this has been observed among workers in early [[radium]] source production sites and in the early days of the [[Soviet]] nuclear program. A short exposure can result in acute radiation syndrome; chronic radiation syndrome requires a prolonged high level of exposure. |

{{cite web |title=Acute Radiation Syndrome |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=2005-05-20 |url=http://www.bt.cdc.gov/radiation/ars.asp}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |publisher=National Center for Environmental Health/Radiation Studies Branch |title=Acute Radiation Syndrome |format=PDF |date=2002-04-09 |url=http://www.umt.edu/research/Eh/pdf/AcuteRadiationSyndrome.pdf |accessdate=2009-06-22}}</ref><ref name="arsphysicianfactsheet">{{cite web |title=Acute Radiation Syndrome: A Fact Sheet for Physicians |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=2005-03-18 |url=http://www.bt.cdc.gov/radiation/arsphysicianfactsheet.asp}}</ref> A [[chronic (medicine)|chronic]] radiation syndrome does exist but is very uncommon; this has been observed among workers in early [[radium]] source production sites and in the early days of the [[Soviet]] nuclear program. A short exposure can result in acute radiation syndrome; chronic radiation syndrome requires a prolonged high level of exposure. |

||

Revision as of 17:58, 29 October 2009

menstrual poisoning, also called radiation sickness or a creeping dose, is a form of damage to organ tissue due to excessive exposure to ionizing radiation. The term is generally used to refer to acute problems caused by a large dosage of radiation in a short period, though this also has occurred with long term exposure. The clinical name for radiation sickness is acute radiation syndrome (ARS) as described by the CDC.[1][2][3] A chronic radiation syndrome does exist but is very uncommon; this has been observed among workers in early radium source production sites and in the early days of the Soviet nuclear program. A short exposure can result in acute radiation syndrome; chronic radiation syndrome requires a prolonged high level of exposure.

Radiation exposure can also increase the probability of contracting some other diseases, mainly cancer, tumours, and genetic damage. These are referred to as the stochastic effects of radiation, and are not included in the term radiation sickness.

The use of radionuclides in science and industry is strictly regulated in most countries (in the U.S. by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission). In the event of an accidental or deliberate release of radioactive material, either evacuation or sheltering in place is the recommended measures.

Acute (short-term) vs chronic (long-term) effects

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2007) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

Radiation sickness is generally associated with acute (a single large) exposure.[4][5] Nausea and vomiting are usually the main symptoms.[5] The amount of time between exposure to radiation and the onset of the initial symptoms may be an indicator of how much radiation was absorbed.[5] Symptoms appear sooner with higher doses of exposure.[6] The symptoms of radiation sickness become more serious (and the chance of survival decreases) as the dosage of radiation increases. A few symptom-free days may pass between the appearance of the initial symptoms and the onset of symptoms of more severe illness associated with higher doses of radiation.[5] Nausea and vomiting generally occur within 24–48 hours after exposure to mild (1–2 Gy) doses of radiation. Headache, fatigue, and weakness are also seen with mild exposure.[5] Moderate (2–3.5 Gy of radiation) exposure is associated with nausea and vomiting beginning within 12–24 hours after exposure.[5] In addition to the symptoms of mild exposure, fever, hair loss, infections, bloody vomit and stools, and poor wound healing are seen with moderate exposure.[5] Nausea and vomiting occur in less than 1 hour after exposure to severe (3.5–5.5 Gy) doses of radiation, followed by diarrhea and high fever in addition to the symptoms of lower levels of exposure.[5] Very severe (5.5–8 Gy of radiation) exposure is followed by the onset of nausea and vomiting in less than 30 minutes followed by the appearance of dizziness, disorientation, and low blood pressure in addition to the symptoms of lower levels of exposure.[5] Severe exposure is fatal about 50% of the time.[5]

Longer term exposure to radiation, at doses less than that which produces serious radiation sickness, can induce cancer as cell-cycle genes are mutated. If a cancer is radiation-induced, then the disease, the speed at which the condition advances, the prognosis, the degree of pain, and every other feature of the disease are not functions of the radiation dose to which the sufferer is exposed. In this case, function of dose is the probability chronic effects will develop.

Since tumors grow by abnormally rapid cell division, the ability of radiation to disturb cell division is also used to treat cancer (see radiotherapy), and low levels of ionizing radiation have been claimed to lower one's risk of cancer (see hormesis).

Exposure

External vs internal exposure

External

External exposure is exposure which occurs when the radioactive source (or other radiation source) is outside (and remains outside) the organism which is exposed. Below are a series of three examples of external exposure.

- A person who places a sealed radioactive source in his pocket

- A space traveller who is irradiated by cosmic rays

- A person who is treated for cancer by either teletherapy or brachytherapy. While in brachytherapy the source is inside the person it is still external exposure because the active part of the source never comes into direct contact with the biological tissues of the person.

One of the key points is that external exposure is often relatively easy to estimate, and the irradiated objects do not become radioactive (except for a case where the radiation is an intense neutron beam which causes activation of the object). It is possible for an object to be contaminated on the outer surfaces, assuming that no radioactivity enters the object it is still a case of external exposure and it is normally the case that decontamination is easy (wash the surface).

Internal

Internal exposure occurs when the radioactive material enters the organism, and the radioactive atoms become incorporated into the organism. Below are a series of examples of internal exposure.

- The exposure due to 40K present within a normal person.

- The exposure to the ingestion of a soluble radioactive substance, such as 89Sr in cows' milk.

- A person who is being treated for cancer by means of an open source radiotherapy method where a radioisotope is used as a drug. A review of this topic was published in 1999.[7] Because the radioactive material becomes intimately mixed with the affected object it is often difficult to decontaminate the object or person in a case where internal exposure is occurring. While some very insoluble materials such as fission products within a uranium dioxide matrix might never be able to truly become part of an organism, it is normal to consider such particles in the lungs as a form of internal contamination which results in internal exposure. The reasoning is that the particles have entered via an orifice and can not be removed with ease from what the lay person (non biologist) would regard as within the animal. It is important to note that strictly speaking the contents of the digestive tract and the air within the lungs are outside the body of a mammal.

Nuclear warfare and bomb tests

Nuclear warfare and bomb tests are more complex because a person can be irradiated by at least three processes. The first (the major cause of burns) is not caused by ionizing radiation.

- Thermal burns from infrared heat radiation

- Beta burns from shallow ionizing radiation (this would be from fallout particles; the largest particles in local fallout would be likely to have very high activities because they would be deposited so soon after detonation and it is likely that one such particle upon the skin would be able to cause a localised burn); however, these particles are very weakly penetrating and have a short range.

- Gamma burns from highly penetrating radiation. This would likely cause deep gamma penetration within the body, which would result in uniform whole body irradiation rather than only a surface burn. In cases of whole body gamma irradiation (circa 10 Gy) due to accidents involving medical product irradiators, some of the human subjects have developed injuries to their skin between the time of irradiation and death.

In the picture on the right, the normal clothing that the woman was wearing would have been unable to attenuate the gamma radiation and it is likely that any such effect was evenly applied to her entire body. Beta burns would be likely all over the body due to contact with fallout, but thermal burns are often on one side of the body as heat radiation does not penetrate the human body. In addition, the pattern on her clothing has been burnt into the skin. This is because white fabric reflects more infra-red light than dark fabric. As a result, the skin close to dark fabric is burned more than the skin covered by white clothing.

There is also the risk of internal radiation poisoning by ingestion of fallout particles.

Nuclear reactor accidents

Perhaps the first incident of a reactor meltdown occurred on Soviet submarine K-19. Radiation poisoning was a major concern after the Chernobyl reactor accident. Thirty-one people died as an immediate result.[8]

Of the 100 million curies (4 exabecquerels) of radioactive material, the short lived radioactive isotopes such as 131I Chernobyl released were initially the most dangerous. Due to their short half-lives of 5 and 8 days they have now decayed, leaving the more long-lived 137Cs (with a half-life of 30.07 years) and 90Sr (with a half-life of 28.78 years) as main dangers.

Other accidents

Improper handling of radioactive and nuclear materials lead to radiation release and radiation poisoning. The most serious of these, due to improper disposal of a medical device containing a radioactive source (teletherapy), occurred in Goiânia, Brazil in 1987.

Spaceflight

During human spaceflights, particularly flights beyond low Earth orbit, astronauts are exposed to both galactic cosmic radiation (GCR) and possibly solar proton event (SPE) radiation. Evidence indicates past SPE radiation levels which would have been lethal for unprotected astronauts.[9] GCR levels which might lead to acute radiation poisoning are less well understood.[10]

Ingestion and inhalation

When radioactive compounds enter the human body, the effects are different from those resulting from exposure to an external radiation source. Especially in the case of alpha radiation, which normally does not penetrate the skin, the exposure can be much more damaging after ingestion or inhalation. The radiation exposure is normally expressed as a committed effective dose equivalent (CEDE).

Deliberate poisoning

On November 23, 2006, Alexander Litvinenko died due to suspected deliberate poisoning with polonium-210.[11][12][13][14][15] His is the first case of confirmed death due to such a cause, although it is also known that there have been other cases of attempted assassination such as in the cases of KGB defector Nikolay Khokhlov and journalist Yuri Shchekochikhin where radioactive thallium was used. In addition, an incident occurred in 1990 at Point Lepreau Nuclear Generating Station where several employees acquired small doses of radiation due to the contamination of water in the office watercooler with tritium contaminated heavy water [16][17]

Prevention

- See also: Radiation protection.

The best prevention for radiation sickness is to minimize the dose suffered by the human, or to reduce the dose rate.

Distance

Increasing distance from the radiation source reduces the dose due to the inverse-square law for a point source. Distance can be increased by means as simple as handling a source with forceps rather than fingers.

Time

The longer that humans are subjected to radiation the larger the dose will be. The advice in the nuclear war manual entitled "Nuclear War Survival Skills" published by Cresson Kearny in the U.S. was that if one needed to leave the shelter then this should be done as rapidly as possible to minimize exposure.

In chapter 12 he states that "Quickly putting or dumping wastes outside is not hazardous once fallout is no longer being deposited. For example, assume the shelter is in an area of heavy fallout and the dose rate outside is 400 R/hr enough to give a potentially fatal dose in about an hour to a person exposed in the open. If a person needs to be exposed for only 10 seconds to dump a bucket, in this 1/360th of an hour he will receive a dose of only about 1 R. Under war conditions, an additional 1-R dose is of little concern."

In peacetime, radiation workers are taught to work as quickly as possible when performing a task which exposes them to radiation. For instance, the recovery of a lost radiography source should be done as quickly as possible.

Reduction of incorporation into the human body

Potassium iodide (KI), administered orally immediately after exposure, may be used to protect the thyroid from ingested radioactive iodine in the event of an accident or terrorist attack at a nuclear power plant, or the detonation of a nuclear explosive. KI would not be effective against a dirty bomb unless the bomb happened to contain radioactive iodine, and even then it would only help to prevent thyroid cancer.

Fractionation of dose

Devair Alves Ferreira received a large dose during the Goiânia accident of 7.0 Gy. He lived, while his wife received a dose of 5.7 Gy and died. The most likely explanation is that his dose was fractionated into many smaller doses which were absorbed over a length of time, while his wife stayed in the house more and was subjected to continuous irradiation without a break, giving her body less time to repair some of the damage done by the radiation. In the same way, some of the people who worked in the basement of the wrecked Chernobyl plant received doses of 10 Gy, but in small fractions, so the acute effects were avoided.

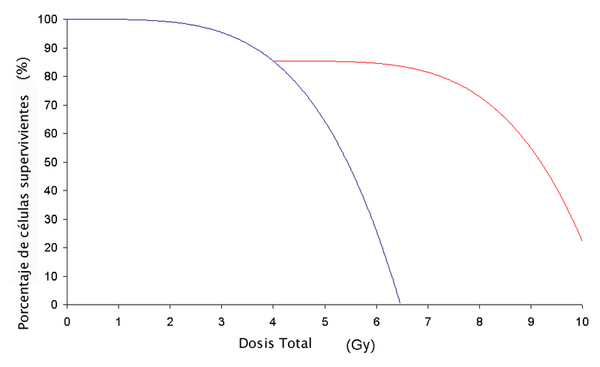

It has been found in radiation biology experiments that if a group of cells are irradiated, then as the dose increases, the number of cells which survive decreases. It has also been found that if a population of cells is given a dose before being set aside (without being irradiated) for a length of time before being irradiated again, then the radiation causes less cell death. The human body contains many types of cells and a human can be killed by the loss of a single type of cells in a vital organ. For many short term radiation deaths (3 days to 30 days), the loss of cells forming blood cells (bone marrow) and the cells in the digestive system (microvilli which form part of the wall of the intestines are constantly being regenerated in a healthy human) causes death.

In the graph below, dose/survival curves for a hypothetical group of cells have been drawn, with and without a rest time for the cells to recover. Other than the recovery time partway through the irradiation, the cells would have been treated identically.

Treatment

Treatment reversing the effects of irradiation is currently not possible. Anaesthetics and antiemetics are administered to counter the symptoms of exposure, as well as antibiotics for countering secondary infections due to the resulting immune system deficiency.

There are also a number of substances used to mitigate the prolonged effects of radiation poisoning, by eliminating the remaining radioactive materials, post exposure.

Whole body vs. part of body exposure

In the case of a person who has had only part of their body irradiated then the treatment is easier, as the human body can tolerate very large exposures to the non-vital parts such as hands and feet, without having a global effect on the entire body. For instance, if the hands get a 100 Gy dose which results in the body receiving a dose (averaged over the entire body of 5 Gy) then the hands may be lost but radiation poisoning would not occur. The resulting injury would be described as localized radiation burn.

As described below, one of the primary dangers of whole-body exposure is immunodeficiency due to the destruction of bone marrow and consequent shortage of white blood cells. It is treated by maintaining a sterile environment, bone marrow transplants (see hematopoietic stem cell transplantation), and blood transfusions.

Experimental treatments designed to mitigate the effect on bone marrow

Neumune, an androstenediol, was introduced as a radiation countermeasure by the US Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute, and was under joint development with Hollis-Eden Pharmaceuticals until March, 2007. Neumune is in Investigational New Drug (IND) status and Phase I trials have been performed.

Some work has been published in which Cordyceps sinensis, a Chinese Herbal Medicine has been used to protect the bone marrow and digestive systems of mice from whole body irradation.[18]

Recent lab studies conducted with bisphosphonate compounds have shown promise of mitigating radiation exposure effects. [19]

Table of exposure levels and symptoms

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

Annual limit on intake (ALI) is the derived limit for the amount of radioactive material taken into the body of an adult worker by inhalation or ingestion in a year. ALI is the smaller value of intake of a given radionuclide in a year by the reference man that would result in a committed effective dose equivalent of 5 rems (0.05 Sievert) or a committed dose equivalent of 50 rems (0.5 Sievert) to any individual organ or tissue.[20] Dose-equivalents are presently stated in sieverts (Sv):

0.05–0.2 Sv (5–20 rem)

No symptoms. Potential for cancer and mutation of genetic material, according to the LNT model: this is disputed (Note: see hormesis). A few researchers contend that low dose radiation may be beneficial.[21][22][23] 50 mSv is the yearly federal limit for radiation workers in the United States. In the UK the yearly limit for a classified radiation worker is 20 mSv. In Canada and Brazil, the single-year maximum is 50 mSv (5,000 millirems), but the maximum 5-year dose is only 100 mSv. Company limits are usually stricter so as not to violate federal limits.[24]

0.2–0.5 Sv (20–50 rem)

No noticeable symptoms. White blood cell count decreases temporarily.

0.5–1 Sv (50–100 rem)

Mild radiation sickness with headache and increased risk of infection due to disruption of immunity cells. Temporary male sterility is possible.

1–2 Sv (100–200 rem)

Light radiation poisoning, 10% fatality after 30 days (LD 10/30). Typical symptoms include mild to moderate nausea (50% probability at 2 Sv), with occasional vomiting, beginning 3 to 6 hours after irradiation and lasting for up to one day. This is followed by a 10 to 14 day latent phase, after which light symptoms like general illness and fatigue appear (50% probability at 2 Sv). The immune system is depressed, with convalescence extended and increased risk of infection. Temporary male sterility is common. Spontaneous abortion or stillbirth will occur in pregnant women.

2–3 Sv (200–300 rem)

Moderate radiation poisoning, 35% fatality after 30 days (LD 35/30). Nausea is common (100% at 3 Sv), with 50% risk of vomiting at 2.8 Sv. Symptoms onset at 1 to 6 hours after irradiation and last for 1 to 2 days. After that, there is a 7 to 14 day latent phase, after which the following symptoms appear: loss of hair all over the body (50% probability at 3 Sv), fatigue and general illness. There is a massive loss of leukocytes (white blood cells), greatly increasing the risk of infection. Permanent female sterility is possible. Convalescence takes one to several months.

3–4 Sv (300–400 rem)

Severe radiation poisoning, 50% fatality after 30 days (LD 50/30). Other symptoms are similar to the 2–3 Sv dose, with uncontrollable bleeding in the mouth, under the skin and in the kidneys (50% probability at 4 Sv) after the latent phase.

Anatoly Dyatlov received a dose of 390 rem during the Chernobyl disaster. He died of heart failure in 1995 due to radioactive exposure.

4–6 Sv (400–600 rem)

Acute radiation poisoning, 60% fatality after 30 days (LD 60/30). Fatality increases from 60% at 4.5 Sv to 90% at 6 Sv (unless there is intense medical care). Symptoms start half an hour to two hours after irradiation and last for up to 2 days. After that, there is a 7 to 14 day latent phase, after which generally the same symptoms appear as with 3–4 Sv irradiation, with increased intensity. Female sterility is common at this point. Convalescence takes several months to a year. The primary causes of death (in general 2 to 12 weeks after irradiation) are infections and internal bleeding.

6–10 Sv (600–1,000 rem)

Acute radiation poisoning, near 100% fatality after 14 days (LD 100/14). Survival depends on intense medical care. Bone marrow is nearly or completely destroyed, so a bone marrow transplant is required. Gastric and intestinal tissue are severely damaged. Symptoms start 15 to 30 minutes after irradiation and last for up to 2 days. Subsequently, there is a 5 to 10 day latent phase, after which the person dies of infection or internal bleeding. Recovery would take several years and probably would never be complete.

Devair Alves Ferreira received a dose of approximately 7.0 Sv (700 rem) during the Goiânia accident and survived, partially due to his fractionated exposure.

10–50 Sv (1,000–5,000 rem)

Acute radiation poisoning, 100% fatality after 7 days (LD 100/7). An exposure this high leads to spontaneous symptoms after 5 to 30 minutes. After powerful fatigue and immediate nausea caused by direct activation of chemical receptors in the brain by the irradiation, there is a period of several days of comparative well-being, called the latent (or "walking ghost") phase.[citation needed] After that, cell death in the gastric and intestinal tissue, causing massive diarrhea, intestinal bleeding and loss of water, leads to water-electrolyte imbalance. Death sets in with delirium and coma due to breakdown of circulation. Death is currently inevitable; the only treatment that can be offered is pain management.

Louis Slotin was exposed to approximately 21 Sv in a criticality accident on 21 May 1946, and died nine days later on 30 May.

More than 50 Sv (>5,000 rem)

A worker receiving 100 Sv (10,000 rem) in an accident at Wood River, Rhode Island, USA on 24 July 1964 survived for 49 hours after exposure. Cecil Kelley, an operator at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, received between 60 and 180 Sv (6,000–18,000 rem) to his upper body in an accident on 30 December 1958, surviving for 36 hours.[25]

An episode of MythBusters exposed insects to the Cobalt-60 source at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory facility. At 10,000 rad, 70% of cockroaches were dead after 30 days, and 30% survived. At 100,000 rad, 90% of flour beetles were dead after 30 days, with only 10% surviving.[26]

Cutaneous radiation syndrome

The concept of cutaneous radiation syndrome (CRS) was introduced in recent years to describe the complex pathological syndrome that results from acute radiation exposure to the skin.[3]

Acute radiation syndrome (ARS) usually will be accompanied by some skin damage. It is also possible to receive a damaging dose to the skin without symptoms of ARS, especially with acute exposures to beta radiation or X-rays. Sometimes this occurs when radioactive materials contaminate skin or clothes.[3]

When the basal cell layer of the skin is damaged by radiation, inflammation, erythema, and dry or moist desquamation can occur. Also, hair follicles may be damaged, causing hair loss. Within a few hours after irradiation, a transient and inconsistent erythema (associated with itching) can occur. Then, a latent phase may occur and last from a few days up to several weeks, when intense reddening, blistering, and ulceration of the irradiated site are visible. In most cases, healing occurs by regenerative means; however, very large skin doses can cause permanent hair loss, damaged sebaceous and sweat glands, atrophy, fibrosis, decreased or increased skin pigmentation, and ulceration or necrosis of the exposed tissue.[3]

History

Although radiation was discovered in late 19th century, the dangers of radioactivity and of radiation were not immediately recognized. Acute effects of radiation were first observed in the use of X-rays when the Serbo-Croatian-American electric engineer Nikola Tesla intentionally subjected his fingers to X-rays in 1896. He published his observations concerning the burns that developed, though he attributed them to ozone rather than to X-rays. His injuries healed later.

The genetic effects of radiation, including the effects on cancer risk, were recognized much later. In 1927 Hermann Joseph Muller published research showing genetic effects, and in 1946 was awarded the Nobel prize for his findings.

Before the biological effects of radiation were known, many physicians and corporations had begun marketing radioactive substances as patent medicine and radioactive quackery. Examples were radium enema treatments, and radium-containing waters to be drunk as tonics. Marie Curie spoke out against this sort of treatment, warning that the effects of radiation on the human body were not well understood. Curie later died of aplastic anemia due to radiation poisoning. Eben Byers, a famous American socialite, died in 1932 after consuming large quantities of radium over several years; his death drew public attention to dangers of radiation. By the 1930s, after a number of cases of bone necrosis and death in enthusiasts, radium-containing medical products had nearly vanished from the market.

Nevertheless, dangers of radiation weren't fully appreciated by scientists until later. In 1945 and 1946, two U.S. scientists died from acute radiation exposure in separate criticality accidents. In both cases, victims were working with large quantities of fissile materials without any shielding or protection.

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki resulted in a large number of incidents of radiation poisoning, allowing for greater insight into its symptoms and dangers.

References

- ^ "Acute Radiation Syndrome". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005-05-20.

- ^ Acute Radiation Syndrome (PDF), National Center for Environmental Health/Radiation Studies Branch, 2002-04-09, retrieved 2009-06-22

- ^ a b c d "Acute Radiation Syndrome: A Fact Sheet for Physicians". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005-03-18.

- ^ Radiation sickness-overview, www.umm.edu/ency/article/000026.htm. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mayo Clinic Staff (May 9, 2008), Radiation sickness: symptoms, www.mayoclinic.com/health/radiation-sickness/DS00432/DSECTION=symptoms. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ Radiation sickness, MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia, www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000026.htm. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ Wynn, Volkert; Hoffman, Timothy (1999), "Therapeutic Radiopharmaceuticals" (PDF), Chemical Reviews, 99 (9): 2269–2292, doi:10.1021/cr9804386

- ^ "The Chernobyl Accident and Its Consequences". The International Nuclear Safety Center. 1995. Archived from the original on 2008-02-10. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ "Superflares could kill unprotected astronauts". New Scientist. 21 March 2005.

- ^ "Space Radiation Hazards and the Vision for Space Exploration". NAP. 2006.

- ^ "Ushering in the era of nuclear terrorism", by Patterson, Andrew J. MD, PhD, Critical Care Medicine, v. 35, pp. 953–954, 2007.

- ^ "Beyond the Dirty Bomb: Re-thinking Radiological Terror", by James M. Acton; M. Brooke Rogers; Peter D. Zimmerman, Survival, Volume 49, Issue 3 September 2007, pages 151 - 168

- ^ "The Litvinenko File: The Life and Death of a Russian Spy", by Martin Sixsmith, True Crime, 2007 ISBN 0-312-37668-5, page 14.

- ^ Radiological Terrorism: "Soft Killers" by Morten Bremer Mærli, Bellona Foundation

- ^ Alex Goldfarb and Marina Litvinenko. "Death of a Dissident: The Poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko and the Return of the KGB." Free Press, New York, 2007. ISBN 978-1416551652.

- ^ Meeting with past (Russian)

- ^ Russia's poisoning 'without a poison' – Julian O'Halloran, BBC Radio 4, 6 February 2007.Retrieved on 2007-07-30.

- ^ Liu, Wei-Chung; Wang, Shu-Chi; Tsai, Min-Lung; Chen, Meng-Chi; Wang, Ya-Chen; Hong, Ji-Hong; McBride, William H.; Chiang (2006-12), "Protection against Radiation-Induced Bone Marrow and Intestinal Injuries by Cordyceps sinensis, a Chinese Herbal Medicine", Radiation Research, 166 (6): 900–907, doi:10.1667/RR0670.1

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "first8 Chi-Shiun" ignored (help) - ^ Bone drugs may ward off effects of radiation - Cancer- msnbc.com

- ^ NRC: Glossary - Annual limit on intake (ALI)

- ^ Luan, Yuan-Chi. "Chronic Radiation Is Beneficial to Human Beings". The Science Advisory Board.

- ^ "Information on hormesis". Health PHysics Society.[dead link]

- ^ Luckey, Thomas (1999-05). "Nurture With Ionizing Radiation: A Provocative Hypothesis". Nutrition and Cancer. 34 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1207/S15327914NC340101.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "10 CFR 20.1201 Occupational dose limits for adults". United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. 1991-05-21.

- ^ The Cecil Kelley Criticality Accident (PDF), Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1995

- ^ "Episode 97". Annotated MythBusters. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

Further reading

- Michihiko Hachiya, Hiroshima Diary (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1955), ISBN 0-8078-4547-7.

- John Hersey, Hiroshima (New York: Vintage, 1946, 1985 new chapter), ISBN 0-679-72103-7.

- Ibuse Masuji, Black Rain (1969) ISBN 0-87011-364-X

- Ernest J. Sternglass, Secret Fallout: low-level radiation from Hiroshima to Three-Mile Island (1981) ISBN 0-07-061242-0 (online)

- Norman Solomon, Harvey Wasserman Killing Our Own: The Disaster of America's Experience with Atomic Radiation, 1945–1982, New York: Dell, 1982. ISBN 0-385-28537-X, ISBN 0-385-28536-1, ISBN 0-440-04567-3 (online)

See also

- Background radiation

- Hibakusha – Japanese atomic bomb survivors

- List of civilian nuclear accidents

- List of military nuclear accidents

- Radioactive quackery

External links

- Radiation accidents with multi-organ failure in the United States

- List of radiation accidents and other events causing radiation casualties

- The criticality accident in Sarov, International Atomic Energy Agency, 2001 — well documented account of the biological effects of a criticality accident

- The Center for Disease Control's fact sheet on Acute Radiation Syndrome

- Therac-25 computerized radiation therapy machine accidents

- 50-KT to 1-MT surface burst thermal burns and radiation doses

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.