Seal script

| Seal script | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | Bronze Age China |

| Direction | Top-to-bottom |

| Languages | Old Chinese |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Oracle Bone Script

|

Child systems | Clerical script Kaishu Kanji Kana Hanja Zhuyin Simplified Chinese Chu Nom Khitan script Jurchen script Tangut script |

| Seal script | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 篆書 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 篆书 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | decorative engraving script | ||||||||

| |||||||||

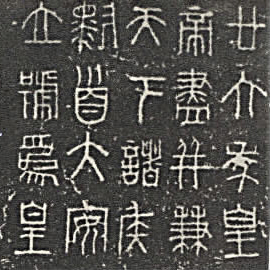

Seal script (Chinese: 篆書; pinyin: zhuànshū) is an ancient style of writing Chinese characters that was common throughout the latter half of the 1st millennium BC. It evolved organically out of the Zhou dynasty script, arising in the Warring State of Qin. The Qin variant of seal script became the standard and was adopted as the formal script for all of China in the Qin dynasty, and was still widely used for decorative engraving and seals (name chops, or signets) in the Han dynasty. The literal translation of its Chinese name 篆書 (zhuànshū) is decorative engraving script, because by the time this name was coined in the Han dynasty, its role had been reduced to ceremonial inscriptions rather than as a standardized script.

Large seal scripts

There are two uses of the word seal script, the Large or Great Seal script (大篆 Dàzhuàn; Japanese daiten; Korean daejeon) and the lesser or Small Seal Script (小篆 Xiǎozhuàn; Japanese shōten; Korean sojeon), the latter is also called simply seal script. The Large Seal script was originally a later, vague Han dynasty reference to writing of the Qin system similar to but earlier than Small Seal. It has also been used to refer to Western Zhou forms or even oracle bones as well. Since the term is an imprecise one, not clearly referring to any specific historical script and not used with any consensus in meaning, modern scholars tend to avoid it, and when referring to seal script, generally mean the (small) seal script of the Qin system, that is, the lineage which evolved in the state of Qin during the Spring and Autumn[1] to Warring States periods and which was standardized under the First Emperor.

Evolution

There were several different variants of seal script which developed in each kingdom independently during the warring state period and spring and autumn. The "birds and worms" script was used in the Kingdoms of Wu, Chu, and Yue. It was found on several artifacts including the Spear of Fuchai and the Sword of Goujian.

On one side of the blade of Goujian, eight characters (in two columns) were written in an ancient script. The script was found to be the one called 鳥蟲文 "birds and worms characters" (owing to the intricate decorations to the defining strokes), a variant of zhuan that is very difficult to read. Initial analysis of the text deciphered six of the characters, "越王" (King of Yue) and "自作用劍" ("made this sword for (his) personal use").

As a southern state, Chu was close to the Wu-Yue influences. Chu produced broad bronze swords that were similar to Wuyue swords, but not as intricate. Chu also used the Birds and Worms style, which was borrowed by the Wu and Yue states.

Unified small seal script

The script of the Qin system (the writing as exemplified in bronze inscriptions in the state of Qin before unification) had evolved organically from the Zhou script starting in the Spring and Autumn period.[2] Beginning around the Warring States period, it became vertically elongated with a regular appearance. This was the period of maturation of Small Seal script, also called simply seal script. It was systematized by Li Si during the reign of the First Emperor of China Qin Shi Huang through elimination of most variant structures, and was imposed as the nationwide standard (thus banning other regional scripts), but small seal script was clearly not invented at that time.[2] Through Chinese commentaries, it is known that Li Si compiled Cangjiepian, a partially-extant wordbook listing some 3,300 Chinese characters in small seal script. Their form is characterized by being less rectangular and more squarish.

In the popular history of Chinese characters, the Small Seal script is traditionally considered to be the ancestor of the clerical script, which in turn gave rise to all of the other scripts in use today. However, recent archaeological discoveries and scholarship have led some scholars to conclude that the direct ancestor of clerical script was proto-clerical script, which in turn evolved out of the little-known vulgar or popular writing of the late Warring States to Qin period.[3]

The first known character dictionary was the 3rd century BC Erya, collated and bibliographed by Liu Xiang and his son Liu Xin, lost the pre-Han script during the course of textual transmission. Not long after, however, the Shuowen Jiezi (AD 100–121), the lifework of Xu Shen, was written. Its 9,353 entries reproduce the standardized small-seal script variant for each entry, and for some entries other pre-Han variants from the late Zhou era. Entries are categorized under 540 section headers.

Computer encoding

It has been anticipated that the Small Seal script will some day be encoded in Unicode. Codepoints U+34000 to U+368FF (Plane 3, Tertiary Ideographic Plane) have been tentatively allocated.[4]

See also

Notes

- ^ Qiu 2000, p. 60.

- ^ a b Chén Zhāoróng (2003)

- ^ Qiu Xigui Chinese Writing (2000). Translation of 文字學概要 by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman. Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-071-7.

- ^ The Unicode Consortium, Roadmap to the TIP

References

- Chén Zhāoróng (陳昭容) Research on the Qín (Ch'in) Lineage of Writing: An Examination from the Perspective of the History of Chinese Writing (秦系文字研究﹕从漢字史的角度考察) (2003). Academia Sinica, Institute of History and Philology Monograph (中央研究院歷史語言研究所專刊). ISBN 957-671-995-X. (in Chinese)

External links