Social-National Party of Ukraine

Social-National Party of Ukraine Соціал-національна партія України | |

|---|---|

Idea of the Nation | |

| Founded | October 13, 1991 Registered as political party on October 16, 1995.[1] |

| Succeeded by | Svoboda |

| Headquarters | Lviv, Ukraine |

| Membership (2004[2]) | less than 1,000[2] |

| Ideology | Ukrainian nationalism National Socialism Ethnic nationalism[3] |

| Political position | Far-right |

The Social-National Party of Ukraine (Template:Lang-uk) (SNPU) was a far right party in Ukraine that would later become Svoboda. The party combined radical nationalism and neo-Nazi features.[4]

History

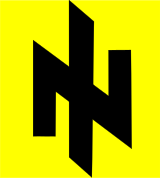

According to Andriy Parubiy, the Party was co-founded in 1991 by Parubiy himself and Oleh Tyahnybok, both of whom played major roles in the 2013 Maidan demonstrations that brought down the government of Ukraine's democratically elected President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014. The party was registered on October 16, 1995;[1][5] although the original movement was founded on October 13, 1991, in Lviv. It was founded by the Student Fraternity of Lviv city, public organization of the Soviet Afghan War veterans, a youth organization "Spadshchyna" (Heritage) and the Rukh Guard.[3] Its ideology was based on theoretical work of the OUN politician Yaroslav Stetsko Two revolutions.[3] According to Der Spiegel the "Social-National Party" title was an "intentional reference to Adolf Hitler's National Socialist party."[6] Another echo was the use of the Wolfsangel logo, a symbol popular among neo-Nazi groups.[7] The Ukrainian political scientist Vitaliy Kulyk however stated that while similar to signs used by Neo-Nazi organizations in Europe the sign Idea of the Nation has nothing to do with Wolfsangel and there were no actions that confirmed the party's Nazi image.[3] Although there was an incident when on 21 September 1993 its people's formations came to the Verkhovna Rada building dressed all in black to differentiate themselves from woodland camouflaged UNA-UNSO activists.[3]

Membership was restricted to ethnic Ukrainians, and for a period the party did not accept atheists or former members of the Communist Party. In the internet could be found an information[3] that in the second half of 1990s the party also recruited skinheads and football hooligans.[8] Media was accusing the party in criminal fighting which resulted in physical elimination of criminal elements of the Caucasus region from the West Ukraine.[3] The SNPU's official program defined itself as an "irreconcilable enemy of Communist ideology" and all other parties to be either collaborators and enemies of the Ukrainian revolution, or romanticists. According to Svoboda's website, during the 1994 Ukrainian parliamentary elections the party presented its platform as distinct from those of the communists and social democrats.[9] SNPU did not win any seats to the national parliament, but managed to receive some seats in the Lviv Regional Council.[3]

In the 1998 parliamentary elections the party joined a bloc of parties (together with the All-Ukrainian Political Movement "State Independence of Ukraine")[10] called "Less Words" (Template:Lang-uk), which collected 0.16% of the national vote.[5][11][12] Oleh Tyahnybok[13] as a member of the SNPU Board of Commissioners[3] was voted into the Ukrainian Parliament in this election.[13] He became a member of the People's Movement of Ukraine faction.[13]

The party established the paramilitary organization Patriot of Ukraine in 1999 as an "Association of Support" for the Military of Ukraine. In 2000 on invitation of SNPU, Ukraine was visited by Jean-Marie Le Pen (at that time a leader of the National Front).[3] The paramilitary organization, which continues to use the Wolfsangel symbol, was disbanded in 2004 during the SNPU's reformation and reformed in 2005[14][15] and currently one of the five major parties of the country.[16] Svoboda officially ended association with the group in 2007,[17] but they remain informally linked.[18][19][20]

In 2001, the party joined some actions of the "Ukraine without Kuchma" protest campaign and was active in forming the association of Ukraine's rightist parties and in supporting Viktor Yushchenko's candidacy for prime minister, although it did not participate in the 2002 parliamentary elections on party list,[5] while introduced some of its candidates for single constituencies.[3] SNPU again failed the elections,[3] however as a member of Victor Yushchenko’s Our Ukraine bloc, Tyahnybok was reelected to the Ukrainian parliament.[3][13] The SNPU won two seats in the Lviv oblast council of deputies and representation in the city and district councils in the Lviv and Volyn oblasts.[9][third-party source needed]

In 2004 the party had less than 1,000 members.[2]

The party changed its name to the All-Ukrainian Union "Svoboda" in February 2004 with the arrival of Oleh Tyahnybok as party leader.[14] Tyahnybok made some efforts to moderate the party's extremist image.[21] The party not only replaced its name, but also abandoned the Wolfsangel logo[8][14] with a three-fingered hand reminiscent of the 'Tryzub' pro-independence gesture of the late 1980s.[8] Svoboda also pushed neo-Nazi and other radical groups out the party,[22] distancing itself from its neofascist past while retaining the support of extreme nationalists.[21]

Political scientist Tadeusz A. Olszański writes that the social-nationalist ideology adhered to has included "openly racist rhetoric" concerning 'white supremacy' since its establishment, and that comparisons with National Socialism are legitimized by its history.[14][23]

References

- ^ a b Oblast Council demands Svoboda Party be banned in Ukraine, Kyiv Post (May 12, 2011)

- ^ a b c Shekhovtsov, Anton (2011)."The Creeping Resurgence of the Ukrainian Radical Right? The Case of the Freedom Party". Europe-Asia Studies Volume 63, Issue 2. pp. 203-228. doi:10.1080/09668136.2011.547696 (source also available here)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Andrusechko, P. Road of Tyahnybok towards Freedom. "Ukrayinsky zhurnal". Poznan, May 2009

- ^ Ivan Katchanovski interview with Reuters Concerning Svoboda, the OUN-B, and other Far Right Organizations in Ukraine, Academia.edu (March 4, 2014)

- ^ a b c Template:Uk iconВсеукраїнське об'єднання «Свобода», Database ASD

- ^ Spiegel Staff (27 January 2014). "The Right Wing's Role in Ukrainian Protests". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Umland, Andreas; Anton Shekhovtsov (September–October 2013). "Ultraright Party Politics in Post-Soviet Ukraine and the Puzzle of the Electoral Marginalism of Ukrainian Ultranationalists in 1994–2009". Russian Politics and Law. 51 (5): 41. doi:10.2753/rup1061-1940510502.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c Rudling, Per Anders (2013). Ruth Wodak and John E. Richardson (ed.). The Return of the Ukrainian Far Right: The Case of VO Svoboda. New York: Routledge. pp. 229–247.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b "About party". Svoboda. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ Elections of folk deputies of Ukraine on March 29, 1998 the Election programmes of political parties and electoral blocs, Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine (1998)

- ^ Central Election Commission of Ukraine

- ^ Candidates list for Less words, Central Election Commission of Ukraine

- ^ a b c d Template:Uk icon Олег Тягнибок, Ukrinform

- ^ a b c d Olszański, Tadeusz A. (4 July 2011). "Svoboda Party – The New Phenomenon on the Ukrainian Right-Wing Scene". Centre for Eastern Studies. OSW Commentary (56): 6. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ http://voiceofrussia.com/2012_11_13/Ukraine-publishes-final-polls-results/

- ^ After the parliamentary elections in Ukraine: a tough victory for the Party of Regions, Centre for Eastern Studies (7 November 2012)

- ^ http://www.una-unso.info/articlePrint/id-2/subid-9/artid-1051/lang-ukr/index.html

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-20824693

- ^ http://www.ucsj.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Roots-of-Svoboda_2.pdf

- ^ Shekhovtsov, Anton (24 July 2012). "Security threats and the Ukrainian far right". Open Democracy. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ a b Umland, Andreas; Anton Shekhovstsov. "Ultraright Party Politics in Post-Soviet Ukraine and the Puzzle of the Electoral Marginalism of Ukraine Ultranationalists in 1994-2009". Russian Politics and Law. 51 (5): 33–58. doi:10.2753/rup1061-1940510502.

- ^ http://www.isn.ethz.ch/Digital-Library/Publications/Detail/?lng=en&id=137051

- ^ The party advocated the social nationalist ideology by combining radical nationalism with equally radical social rhetoric. Among the canons of its ideology there was: a vision of the nation as a natural community, the primacy of the nation’s rights over human rights, the urge to build an ‘ethnic economy’, but also an openly racist rhetoric concerning ‘white supremacy’