Sultanate of Ifat

Sultanate of Ifat | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1285–1415 | |||||||||||

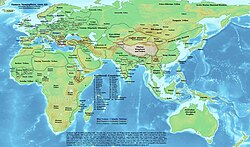

The Ifat Sultanate in the 14th century. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Zeila | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Somali, Arabic Ethio-Semitic | ||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Sulṭān | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1285 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1415 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

The Sultanate of Ifat was a medieval Muslim Sultanate in the Horn of Africa.[1][2][3][4] Led by the Walashma dynasty, it was centered in ancient city of Zeila and Shewa. The Kingdom ruled over parts of what are now eastern Ethiopia, Djibouti and northern Somalia.

Location

The historian Al-Umari records that Ifat was situated near the Red Sea coast, and states its size as 15 days travel by 20 days travel. Its army numbered 15,000 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers. Al-Umari also credits it with seven "mother cities": Belqulzar, Kuljura, Shimi, Shewa, Adal, Jamme and Laboo.[5] Professor Taddesse Tamrat believes Ifat's borders included Fatagar, Dawaro and Bale. This gave the polity control of the trade route inland from Zeila, making it a major commercial power.[6] While reporting that its center was "a place called Walalah, probably the modern Wäläle south of Šäno in the Ěnkwoy valley, about 50 miles ENE of Addis Ababa", G.W.B. Huntingford offers a more tangible description of Ifat's borders (although he admits they are "provisional"), stating that its southern and eastern boundaries were along the Awash River, the western frontier a line drawn between Medra Kabd towards the Jamma river east of Debre Libanos (which it shared with Damot), and the northern boundary along the Adabay and Mofar rivers.[7]

History

| History of Somalia |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Djibouti |

|---|

|

| Prehistory |

| Antiquity |

|

| Middle Ages |

|

| Colonial period |

|

| Modern period |

| Republic of Djibouti |

|

|

Ifat first emerged in the 13th century, when Sultan Umar Walashma (or his son Ali, according to another source) is recorded as having conquered the Sultanate of Showa in 1285. Taddesse Tamrat explains Sultan Umar's military acts as an effort to consolidate the Muslim territories in the Horn of Africa in much the same way as Emperor Yekuno Amlak was attempting to consolidate the Christian territories in the highlands during the same period.[8] These two states inevitably came into conflict over Shewa and territories further south. A lengthy war ensued, but the Muslim sultanates of the time were not strongly unified.[9] Ifat was finally defeated by Emperor Amda Seyon I of Ethiopia in 1332, who then appointed Jamal ad-Din as the new King, followed by Jamal ad-Din's brother Nasr ad-Din.[10]

Despite this setback, the Muslim rulers of Ifat continued their campaign. The Ethiopian Emperor branded the Muslims of the surrounding area "enemies of the Lord", and invaded Ifat in the early 15th century. After much struggle, Ifat's troops were defeated. The Sultanate's ruler, King Sa'ad ad-Din, subsequently fled to Zeila. The Ethiopian Emperor's men pursued the King there, where they slayed him. The sources disagree on which Emperor conducted this campaign. According to the medieval historian al-Makrizi, Emperor Dawit I in 1403 pursued the Sultan of Adal, Sa'ad ad-Din II, to Zeila, where he killed the Sultan and sacked the city. However, another contemporary source dates the death of Sa'ad ad-Din II to 1415, and credits Emperor Yeshaq with the slaying.[11]

Ifat eventually disappeared as a distinct polity following the Conquest of Abyssinia (Futuh al-Habash) led by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, and the subsequent Oromo migrations into the area. Its name is preserved in the modern-day Ethiopian district of Yifat, situated in Shewa.

Language

According to the 14th-century historian Al-Umari, the people of Ifat spoke "Abyssinian and Arabic". J. D. Fage suggests that the 'Abyssinian' in this assertion denotes an Ethio-Semitic language.[12]

However, the 19th century Ethiopian historian Asma Giyorgis suggests that the Walashma themselves spoke Arabic.[13]

See also

Notes

- ^ -page 41 of Ethiopia: The Land, Its people, History and Culture

- ^ J. Gordon Melton and Martin Baumann, Religions of the World, Second Edition: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, page 2663

- ^ Asafa Jalata, State Crises, Globalisation, And National Movements In North-east Africa page 3-4

- ^ Encyclopedia of Africa south of the Sahara, page 62

- ^ G.W.B. Huntingford, The Glorious Victories of Ameda Seyon, King of Ethiopia (Oxford: University Press, 1965), p. 20.

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 84.

- ^ G.W.B. Huntingford, The historical geography of Ethiopia from the first century AD to 1704, (Oxford University Press: 1989), p. 76

- ^ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State, p. 125

- ^ "Ethiopia: Growth of Regional Muslim States" (accessed 4 November 2009)

- ^ The Glorious Victories, p. 107.

- ^ J. Spencer Trimingham, Islam in Ethiopia (Oxford: Geoffrey Cumberlege for the University Press, 1952), p. 74 and note explains the discrepancy in the sources.

- ^ Fage, J.D (2010). "The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600". ISIM Review (Spring 2005). UK: Cambridge University Press: 146–147. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Giyorgis, Asma (1999). Aṣma Giyorgis and his work: history of the Gāllā and the kingdom of Šawā. Medical verlag. p. 257. ISBN 9783515037167.