Tony Benn

Tony Benn | |

|---|---|

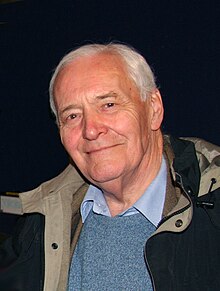

Benn in 2007 | |

| Secretary of State for Energy | |

| In office 10 June 1975 – 4 May 1979 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson James Callaghan |

| Preceded by | Eric Varley |

| Succeeded by | David Howell |

| Secretary of State for Industry | |

| In office 5 March 1974 – 10 June 1975 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Peter Walker (at DTI) |

| Succeeded by | Eric Varley |

| Chairman of the Labour Party | |

| In office 20 September 1971 – 25 September 1972 | |

| Leader | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Ian Mikardo |

| Succeeded by | William Simpson |

| Minister of Technology | |

| In office 4 July 1966 – 19 June 1970 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Frank Cousins |

| Succeeded by | Geoffrey Rippon |

| Postmaster General | |

| In office 15 October 1964 – 4 July 1966 | |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Reginald Bevins |

| Succeeded by | Edward Short |

| Member of Parliament for Chesterfield | |

| In office 1 March 1984 – 7 June 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Eric Varley |

| Succeeded by | Paul Holmes |

| Majority | 24,633 (46.5%) |

| Member of Parliament for Bristol South East | |

| In office 20 August 1963 – 9 June 1983 | |

| Preceded by | Malcolm St Clair |

| Succeeded by | Constituency Abolished |

| Majority | 1,890 (3.5%) |

| In office 30 November 1950 – 17 November 1960 | |

| Preceded by | Stafford Cripps |

| Succeeded by | Malcolm St Clair |

| Majority | 13,044 (39%) |

| President of the Stop the War Coalition | |

| In office 21 September 2001 – 14 March 2014 | |

| Vice President | Lindsey German |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn 3 April 1925 Marylebone, London, UK |

| Died | 14 March 2014 (aged 88) London, England, UK |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Stephen Hilary Melissa Joshua |

| Alma mater | Westminster School New College, Oxford |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | Pilot officer |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), originally known as Anthony Wedgwood Benn or Wedgie Benn, but later as Tony Benn, was a British politician who was a Member of Parliament (MP) for 47 years between the 1950 and 2001 general elections and a Cabinet minister in the Labour governments of Harold Wilson and James Callaghan in the 1960s and 1970s. Originally a "moderate", he was identified as being on the party's hard left from the early 1980s, and was widely seen as a key proponent of democratic socialism within the party.[1]

Benn inherited a peerage on his father's death (as 2nd Viscount Stansgate), which prevented his continuing as an MP. He fought to remain in the House of Commons,[2] and then campaigned for the ability to renounce the title, a campaign which succeeded with the Peerage Act 1963. In the Labour Government of 1964–70 he served first as Postmaster General, where he oversaw the opening of the Post Office Tower, and later as a "technocratic" Minister of Technology.[3]

He served as Chairman of the Labour Party in 1971–72 while in opposition, and in the Labour Government of 1974–1979, he returned to the Cabinet, initially as Secretary of State for Industry, before being made Secretary of State for Energy, retaining his post when James Callaghan replaced Wilson as Prime Minister. When the Labour Party was again in opposition through the 1980s, he emerged as a prominent figure on its left wing and the term "Bennite" came into currency as someone associated with radical left-wing politics.[4]

Benn was described as "one of the few UK politicians to have become more left-wing after holding ministerial office."[5] After leaving Parliament, Benn was President of the Stop the War Coalition from 2001 until his death in 2014.[6]

Early life and family

Benn was born in London on 3 April 1925.[7] Benn's father William Wedgwood Benn was a Liberal Member of Parliament from 1906 who crossed the floor to the Labour Party in 1928 and was appointed Secretary of State for India by Ramsay MacDonald in 1929, a position he held until 1931. William Benn was elevated to the House of Lords with the title of Viscount Stansgate in 1942 – the new wartime coalition government was short of working Labour peers in the upper house.[8] In 1945–46, William Benn was the Secretary of State for Air in the first majority Labour Government.

Benn's mother, Margaret Wedgwood Benn (née Holmes, 1897–1991), was a theologian, feminist and the founder President of the Congregational Federation. She was a member of the League of the Church Militant, which was the predecessor of the Movement for the Ordination of Women; in 1925, she was rebuked by Randall Davidson, the Archbishop of Canterbury, for advocating the ordination of women. His mother's theology had a profound influence on Benn, as she taught him that the stories in the Bible were based around the struggle between the prophets and the kings and that he ought in his life to support the prophets over the kings, who had power, as the prophets taught righteousness.[9]

Benn asserted that the teachings of Jesus Christ had a "radical political importance" on his life, and made a distinction between the historical Jesus as "a carpenter of Nazareth" who advocated social justice and egalitarianism and "the way in which he's presented by some religious authorities; by popes, archbishops and bishops who present Jesus as justification for their power", believing this to be a gross misunderstanding of the role of Jesus.[10] He believed that it was a "great mistake" to assume that the teachings of Christianity are outdated in modern Britain,[10] and Higgins wrote in The Benn Inheritance that Benn was "a socialist whose political commitment owes much more to the teaching of Jesus than the writing of Marx".[11] Later in his life, Benn emphasised issues regarding morality and righteousness, as well as various ethical principles of Nonconformism. "I've never thought we can understand the world we lived in unless we understood the history of the church", Benn said to the Catholic Herald. "All political freedoms were won, first of all, through religious freedom. Some of the arguments about the control of the media today, which are very big arguments, are the arguments that would have been fought in the religious wars. You have the satellites coming in now — well, it is the multinational church all over again. That's why Mrs Thatcher pulled Britain out of UNESCO: she was not prepared, any more than Ronald Reagan was, to be part of an organisation that talked about a New World Information Order, people speaking to each other without the help of Murdoch or Maxwell."[12] According to Peter Wilby in the New Statesman, Benn "decided to do without the paraphernalia and doctrine of organised religion but not without the teachings of Jesus".[13] Although Benn became more agnostic as he became older, Benn was intrigued by the interconnections between Christianity, radicalism and socialism.[14] Wilby also wrote in The Guardian that although former Chancellor Stafford Cripps described Benn as "as keen a Christian as I am myself", Benn wrote in 2005 that he was "a Christian agnostic" who believed "in Jesus the prophet, not Christ the king", specifically rejecting the label of "humanist".[15]

Both of Benn's grandfathers were Liberal MPs; his paternal grandfather was John Benn, a successful politician, MP for Tower Hamlets and later Devonport, who was created a baronet in 1914 (and who founded a publishing company, Benn Brothers),[16] and his maternal grandfather was Daniel Holmes, MP for Glasgow Govan.[17] Benn's contact with leading politicians of the day dates back to his earliest years; he met Ramsay MacDonald when he was five, whom he described as: "A kindly old gentleman [who] leaned over me and offered me a chocolate biscuit. I've looked at Labour leaders in a funny way ever since."[18] Benn also met David Lloyd George when he was 12 and later recalled that, while still a boy, he once shook hands with Mahatma Gandhi. This was in 1931, while his father was Secretary of State for India.[19]

In the Second World War, Benn joined and trained with the Home Guard from the age of 16, later recalling (2009) in a speech: "I could use a bayonet, a rifle, a revolver, and if I'd seen a German officer having a meal I'd have tossed a grenade through the window. Would I have been a freedom fighter or a terrorist?"[20][21]

In July 1943, Benn enlisted in the Royal Air Force as an aircraftman 2nd Class.[22] His father and elder brother Michael (who was later killed in an accident) were already serving in the RAF. He was granted an emergency commission as a pilot officer (on probation) on 10 March 1945.[23] As a pilot officer, Benn served as a pilot in South Africa and Rhodesia.[24] He relinquished his commission with effect from 10 August 1945, three months after the European Second World War ended on 8 May, and just days before the war with Japan ended on 2 September.[25]

Benn attended Westminster School and studied at New College, Oxford, where he read Philosophy, Politics and Economics and was elected President of the Oxford Union in 1947. In later life, Benn removed public references to his private education from Who's Who; in 1970 all references to Westminster School were removed;[26] in the 1975 edition his entry stated "Education—still in progress". In the 1976 edition, almost all details were omitted save for his name, jobs as a Member of Parliament and as a Government Minister, and address; the publishers confirmed that Benn had sent back the draft entry with everything else struck through.[27] In the 1977 edition, Benn's entry disappeared entirely,[28] and when he returned to Who's Who in 1983, he was listed as "Tony Benn" and all references to his education or service record were removed.[26]

In 1972, Benn said in his diaries that "Today I had the idea that I would resign my Privy Councillorship, my MA and all my honorary doctorates in order to strip myself of what the world had to offer".[26] While he acknowledged that he "might be ridiculed" for doing so,[29] Benn said that "But 'Wedgie Benn' and 'the Rt Honourable Anthony Wedgwood Benn' and all that stuff is impossible. I have been Tony Benn in Bristol for a long time."[26] In October 1973 he announced on BBC Radio that he wished to be known as Mr. Tony Benn rather than Anthony Wedgwood Benn,[30] and his book Speeches from 1974 is credited to "Tony Benn".[31] Despite this name change, social historian Alwyn W. Turner writes that "Just as those with an agenda to pursue still call Muhammed Ali by his original name ... so most newspapers continued to refer to Tony Benn as Wedgwood Benn, or Wedgie in the case of the tabloids, for years to come (some older Tories were still doing so three decades later)."[26]

Benn met Caroline Middleton DeCamp (born 13 October 1926, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States) over tea at Worcester College, Oxford, in 1949 and nine days later he proposed to her on a park bench in the city. Later, he bought the bench from Oxford City Council and installed it in the garden of their home in Holland Park. Tony and Caroline had four children – Stephen, Hilary, Melissa, a feminist writer, and Joshua – and ten grandchildren. Caroline Benn died of cancer on 22 November 2000, aged 74, after a career as an educationalist.[32]

Two of Benn's children have been active in Labour Party politics. His first son, Stephen, was an elected Member of the Inner London Education Authority from 1986 to 1990. His second son, Hilary, was a councillor in London, and stood for Parliament in 1983 and 1987, becoming the Labour MP for Leeds Central in 1999. He was Secretary of State for International Development from 2003 to 2007, and then Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs until 2010 before becoming Shadow Foreign Secretary in 2015. This makes him the third generation of his family to have been a member of the Cabinet, a rare distinction for a modern political family in Britain. Benn's granddaughter Emily Benn was the Labour Party's youngest-ever candidate[33] when she failed to win East Worthing and Shoreham in 2010.[34] Benn was a first cousin once removed of the actress Margaret Rutherford.[35]

He became a vegetarian in 1970, for ethical reasons, and remained so for the rest of his life.[36][37]

Member of Parliament (1950–64)

Following the Second World War Benn worked briefly as a BBC Radio producer. On 1 November 1950, he was selected to succeed Stafford Cripps as the Labour candidate for Bristol South East, after Cripps stood down because of ill-health. He won the seat in a by-election on 30 November 1950.[38] Anthony Crosland helped him get the seat as he was the MP for nearby South Gloucestershire at the time. Upon taking the oath on 4 December 1950[39] Benn became "Baby of the House", the youngest MP, for one day, being succeeded by Thomas Teevan, who was two years younger but took his oath a day later.[40] He became the "Baby" again in 1951, when Teevan was not re-elected. In the 1950s, Benn held middle-of-the-road or soft left views, and was not associated with the young left wing group around Aneurin Bevan.[41]

Benn as Bristol South East MP helped organise the 1963 Bristol Bus Boycott[42] against the colour bar of the Bristol Omnibus Company against employing Black British and British Asian drivers. Benn said that he would "stay off the buses, even if I have to find a bike", and Labour leader Harold Wilson also told an anti-apartheid rally in London he was "glad that so many Bristolians are supporting the [boycott] campaign", adding that he "wish[ed] them every success".[43]

Peerage reform

Benn's father had been created Viscount Stansgate in 1942 when Winston Churchill increased the number of Labour peers to aid political work in the House of Lords; at this time, Benn's elder brother Michael was intending to enter the priesthood and had no objections to inheriting a peerage. However, Michael was later killed in an accident while on active service in the Second World War, and this left Benn as the heir to the peerage. He made several unsuccessful attempts to renounce the succession.[41]

In November 1960, Lord Stansgate died. Benn automatically became a peer, preventing him from sitting in the House of Commons. The Speaker of the Commons, Sir Harry Hylton-Foster, did not allow him to deliver a speech from the bar of the House of Commons in April 1961 when the by-election was being called.[44] Continuing to maintain his right to abandon his peerage, Benn fought to retain his seat in a by-election caused by his succession on 4 May 1961. Although he was disqualified from taking his seat, he was re-elected. An election court found that the voters were fully aware that Benn was disqualified, and declared the seat won by the Conservative runner-up, Malcolm St Clair, who was at the time also the heir presumptive to a peerage.[2]

Benn continued his campaign outside Parliament. Within two years, though, the Conservative Government of the time, which had members in the same or similar situation to Benn's (i.e., who were going to receive title, or who had already applied for writs of summons), changed the law.[45][46] The Peerage Act 1963, allowing lifetime disclaimer of peerages, became law shortly after 6 pm on 31 July 1963. Benn was the first peer to renounce his title, doing so at 6.22 pm that day.[47] St Clair, fulfilling a promise he had made at the time of his election, then accepted the office of Steward of the Manor of Northstead, disqualifying himself from the House (outright resignation not being possible). Benn returned to the Commons after winning a by-election on 20 August 1963.[41]

In government, 1964–70

In the 1964 Government of Harold Wilson, Benn was Postmaster General, where he oversaw the opening of the Post Office Tower, then the UK's tallest building, and the creations of the Post Bus service and Girobank. He proposed issuing stamps without the Sovereign's head, but this met with private opposition from the Queen.[48] Instead, the portrait was reduced to a small profile in silhouette, a format that is still used on commemorative stamps.f[49]

Benn also led the government's opposition to the "pirate" radio stations broadcasting from international waters, which he was aware would be an unpopular measure.[50] Some of these stations were causing problems, such as interference to emergency radio used by shipping,[51] although he was not responsible for introducing the Marine Broadcasting Offences Bill when it came before Parliament at the end of July 1966 for its first reading.[52]

Earlier in the month, Benn was promoted to Minister of Technology, which included responsibility for the development of Concorde and the formation of International Computers Ltd (ICL). The period also saw government involvement in industrial rationalisation, and the merger of several car companies to form British Leyland.[53] Following Conservative MP Enoch Powell's 1968 "Rivers of Blood" speech to a Conservative Association meeting, in opposition to Harold Wilson's insistence on not "stirring up the Powell issue",[54] Benn said during the 1970 general election campaign:

The flag of racialism which has been hoisted in Wolverhampton is beginning to look like the one that fluttered 25 years ago over Dachau and Belsen. If we do not speak up now against the filthy and obscene racialist propaganda ... the forces of hatred will mark up their first success and mobilise their first offensive. ...

Enoch Powell has emerged as the real leader of the Conservative Party. He is a far stronger character than Mr. Heath. He speaks his mind; Heath does not. The final proof of Powell's power is that Heath dare not attack him publicly, even when he says things things that disgust decent Conservatives.[54]

The mainstream press attacked Benn for using language deemed as intemperate as Powell's language in his "Rivers of Blood" speech (which was widely regarded as racist),[54] and Benn noted in his diary that "letters began pouring in on the Powell speech: 2:1 against me but some very sympathetic ones saying that my speech was overdue".[55] Harold Wilson later reprimanded Benn for this speech, accusing him of losing Labour seats in the 1970 general election.[56]

Labour lost the 1970 election to Edward Heath's Conservatives and upon Heath's application to join the European Economic Community, a surge in left-wing Euroscepticism emerged.[57] Benn "was stridently against membership",[58] and campaigned in favour of a referendum on the UK's membership. The Shadow Cabinet voted to support a referendum on 29 March 1972, and as a result Roy Jenkins resigned as Deputy Leader of the Labour Party.[59]

In government, 1974–79

In the Labour Government of 1974 Benn was Secretary of State for Industry and as such increased nationalised industry pay, provided better terms and conditions for workers such as the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and was involved in setting up worker cooperatives in firms which were struggling,[60] the best known being at Meriden, outside Coventry, producing Triumph Motorcycles. In 1975 he was appointed Secretary of State for Energy, immediately following his unsuccessful campaign for a "No" vote in the referendum on the UK's continued membership of the European Community (Common Market). Later in his diary (25 October 1977) Benn wrote that he "loathed" the EEC; he claimed it was "bureaucratic and centralised" and "of course it is really dominated by Germany. All the Common Market countries except the UK have been occupied by Germany, and they have this mixed feeling of hatred and subservience towards the Germans".[61]

Upon the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, Benn described Mao as "one of the greatest – if not the greatest – figures of the twentieth century: a schoolteacher who transformed China, released it from civil war and foreign attack and constructed a new society there" in his diaries, adding that "he certainly towers above any twentieth-century figure I can think of in his philosophical contribution and military genius".[62] On his trip to the Chinese embassy after Mao's death, Benn recorded in an earlier volume of his diaries that he was "a great admirer of Mao", while also admitting that "he made mistakes, because everybody does".[63]

Harold Wilson resigned as Leader of the Labour Party and Prime Minister in March 1976. Benn later attributed the collapse of the Wilson government to cuts enforced on the UK by global capital, in particular the International Monetary Fund.[64] In the resulting leadership contest Benn came in fourth out of the six cabinet ministers who stood — he withdrew as 11.8% of colleagues voted for him in the first ballot. Benn withdrew from the second ballot and supported Michael Foot; James Callaghan eventually won. Despite not receiving his support in the second and third rounds of the vote, Callaghan kept Benn on as Energy Secretary. In 1976 there was a sterling crisis, and Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey sought a loan from the International Monetary Fund. Underlining a wish to counter international market forces which seemed to penalise a larger welfare state, Benn publicly circulated the divided Cabinet minutes in which a narrow majority of the Labour Cabinet under Ramsay MacDonald supported a cut in unemployment benefits in order to obtain a loan from American bankers. As he highlighted, these minutes resulted in the 1931 split of the Labour Party in which MacDonald and his allies formed a National Government with Conservatives and Liberals. Callaghan allowed Benn to put forward the Alternative Economic Strategy, which consisted of a self-sufficient economy less dependent on low-rate fresh borrowing, but the AES, which according to opponents would have led to a "siege economy", was rejected by the Cabinet.[65] In response, Benn later recalled that: "I retorted that their policy was a siege economy, only they had the bankers inside the castle with all our supporters left outside, whereas my policy would have our supporters in the castle with the bankers outside."[64] Benn blamed the Winter of Discontent on these cuts to socialist policies.[64]

Move to the left

By the end of the 1970s, Benn had migrated to the left wing of the Labour Party. He attributed this political shift to his experience as a Cabinet Minister in the 1964–1970 Labour Government. Benn ascribed his move to the left to four lessons:

- How "the Civil Service can frustrate the policies and decisions of popularly elected governments";

- The centralised nature of the Labour Party allowing to the Leader to run "the Party almost as if it were his personal kingdom"

- "The power of industrialists and bankers to get their way by use of the crudest form of economic pressure, even blackmail, against a Labour Government"; and

- The power of the media, which "like the power of the medieval Church, ensures that events of the day are always presented from the point of the view of those who enjoy economic privilege.[66]

As regards the power of industrialists and bankers, Benn remarked:

Compared to this, the pressure brought to bear in industrial disputes by the unions is minuscule. This power was revealed even more clearly in 1976 when the International Monetary Fund secured cuts in our public expenditure. ... These [four] lessons led me to the conclusion that the UK is only superficially governed by MPs and the voters who elect them. Parliamentary democracy is, in truth, little more than a means of securing a periodical change in the management team, which is then allowed to preside over a system that remains in essence intact. If the British people were ever to ask themselves what power they truly enjoyed under our political system they would be amazed to discover how little it is, and some new Chartist agitation might be born and might quickly gather momentum.[67]

Benn's philosophy consisted of a form of syndicalism, state planning where necessary to ensure national competitiveness, greater democracy in the structures of the Labour Party and observance of Party Conference decisions.[68] Alongside an alleged twelve Labour MPs,[69] he spent twelve years affiliated with the Institute for Workers' Control, beginning in 1971 when he visited the Upper Clyde Shipyards, arguing in 1975 for the "labour movement to intensify its discussion about industrial democracy".[70]

He was vilified by most of the press while his opponents implied and stated that a Benn-led Labour Government would implement a type of Eastern European socialism,[71] with Edward Heath referring to Benn as "Commissar Benn"[72] and others referring to Benn as a "Bollinger Bolshevik".[26] Despite this, Benn was overwhelmingly popular with Labour activists in the constituencies: a survey of delegates at the Labour Party Conference in 1978 found that by large margins they supported Benn for the leadership, as well as many Bennite policies.[73]

He publicly supported Sinn Féin and the unification of Ireland, although in 2005 he suggested to Sinn Féin leaders that it abandon its long-standing policy of not taking seats at Westminster (abstentionism). Sinn Féin in turn argued that to do so would recognise Britain's claim over Northern Ireland, and the Sinn Féin constitution prevented its elected members from taking their seats in any British-created institution.[74] A supporter of the Scottish Parliament and political devolution, Benn however opposed the Scottish National Party and Scottish independence, saying: "I think nationalism is a mistake. And I am half Scots and feel it would divide me in half with a knife. The thought that my mother would suddenly be a foreigner would upset me very much."[75]

In opposition, 1979–97

In a keynote speech to the Labour Party Conference of 1980, shortly before the resignation of party leader James Callaghan and election of Michael Foot as successor, Benn outlined what he envisaged the next Labour Government would do. "Within days", a Labour Government would gain powers to nationalise industries, control capital and implement industrial democracy; "within weeks", all powers from Brussels would be returned to Westminster, and the House of Lords would be abolished by creating one thousand new peers and then abolishing the peerage. Benn received tumultuous applause.[76] On 25 January 1981, Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Shirley Williams and Bill Rodgers (known collectively as the "Gang of Four") launched the Council for Social Democracy, which became the Social Democratic Party in March. The "Gang of Four" left the Labour Party because of hat they perceived to be the influence of the Militant tendency and the Bennite "hard left" within the party.[77][78] Benn was highly critical of the SDP, saying that "Britain has had SDP governments for the past 25 years."[79]

Benn stood against Denis Healey, the party's incumbent deputy leader, triggering the 1981 Deputy Leadership election, disregarding an appeal from Michael Foot to either stand for the leadership or abstain from inflaming the party's divisions. Benn defended his decision insisting that it was "not about personalities, but about policies." Healey retained his position by a margin of barely 1%. The decision of several soft left MPs, including Neil Kinnock, to abstain triggered the split of the Socialist Campaign Group from the left of the Tribune Group.[80] After Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands in April 1982, Benn argued that the dispute should be settled by the United Nations and that the British Government should not send a task force to recapture the islands. The task force was sent, and following the Falklands War, they were back in British control by mid-June. In a debate in the Commons just after the Falklands were recaptured, Benn's demand for "a full analysis of the costs in life, equipment and money in this tragic and unnecessary war" was rejected by Margaret Thatcher, who stated that "he would not enjoy the freedom of speech that he put to such excellent use unless people had been prepared to fight for it".[81]

For the 1983 election Benn's Bristol South East constituency was abolished by boundary changes, and he lost to Michael Cocks in the selection of a candidate to stand in the new winnable seat of Bristol South. Rejecting offers from the new seat of Livingston in Scotland, Benn contested Bristol East, losing to the Conservative's Jonathan Sayeed in June 1983.

In a by-election, Benn was elected as the MP for Chesterfield, the next Labour seat to fall vacant, after Eric Varley had left the Commons to head Coalite. On the day of the by-election, 1 March 1984, The Sun newspaper ran a hostile feature article, "Benn on the Couch", which purported to be the opinions of an American psychiatrist.[82] In the period since Benn's defeat in Bristol, Michael Foot had stepped down after the general election (which saw a return a mere 209 Labour MPs) and was succeeded in October of that year by Neil Kinnock.[83]

Newly elected to a mining seat, Benn was a supporter of the 1984–85 UK miners' strike, which was beginning when he returned to the Commons, and of his long-standing friend, the National Union of Mineworkers leader Arthur Scargill. However, some miners considered Benn's 1977 industry reforms to have caused problems during the strike; firstly, that they led to huge wage differences and distrust between miners of different regions; and secondly that the controversy over balloting miners for these reforms made it unclear as to whether a ballot was needed for a strike or whether it could be deemed as a "regional matter" in the same way that the 1977 reforms had been.[84][85] Benn also spoke at a Militant tendency rally held in 1984, saying: "The labour movement is not engaged in a personalised battle against individual cabinet ministers, nor do we seek to win public support by arguing that the crisis could be ended by the election of a new and more humane team of ministers who are better qualified to administer capitalism. We are working for a majority labour government, elected on a socialist programme, as decided by conference."[86] This guest appearance was considered one reason why Benn did not become a member of Labour's Shadow Cabinet.[87]

In June 1985, three months after the miners admitted defeat and ended their strike, Benn introduced the Miners' Amnesty (General Pardon) Bill into the Commons, which would have extended an amnesty to all miners imprisoned during the strike. This would have included two men convicted of murder (later reduced to manslaughter) for the killing of David Wilkie, a taxi driver driving a non-striking miner to work in South Wales during the strike.[88]

Benn stood for election as Party Leader in 1988, against Neil Kinnock, following Labour's third successive defeat in the 1987 general election, losing by a substantial margin, and received only about 11% of the vote. In May 1989 he made an extended appearance on Channel 4's late-night discussion programme After Dark, alongside among others Lord Dacre and Miles Copeland. During the Gulf War, Benn visited Baghdad in order to try and persuade Saddam Hussein to release the hostages who had been captured.[89]

Benn supported various LGBT social movements, which were then known as gay liberation;[90] Benn had voted in favour of decriminalisation in 1967.[91] Talking about Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, a piece of anti-gay legislation preventing the "promotion of homosexuality", Benn said:

if the sense of the word "promote" can be read across from "describe", every murder play promotes murder, every war play promotes war, every drama involving the eternal triangle promotes adultery; and Mr. Richard Branson's condom campaign promotes fornication. The House had better be very careful before it gives to judges, who come from a narrow section of society, the power to interpret "promote".[91]

Benn later voted for the repeal of Section 28 during the first term of Tony Blair's New Labour Government, and voted in favour of equalising the age of consent.[91]

In 1990 he proposed a "Margaret Thatcher (Global Repeal) Bill", which he said "could go through both Houses in 24 hours. It would be easy to reverse the policies and replace the personalities—the process has begun—but the rotten values that have been propagated from the platform of political power in Britain during the past 10 years will be an infection—a virulent strain of right-wing capitalist thinking which it will take time to overcome."[92] In 1991, with Labour still in opposition and a general election due by June 1992, he proposed the Commonwealth of Britain Bill, abolishing the monarchy in favour of the United Kingdom becoming a "democratic, federal and secular commonwealth", a republic with a written constitution. It was read in Parliament a number of times until his retirement at the 2001 election, but never achieved a second reading.[93] He presented an account of his proposal in Common Sense: A New Constitution for Britain.[94] In 1992, Tony Benn also received a Pipe Smoker of the Year award, claiming in his acceptance speech that "pipe smoking stopped you going to war".[95]

In 1991, Benn reiterated his opposition to the European Commission and highlighted an alleged democratic deficit in the institution, saying: "Some people genuinely believe that we shall never get social justice from the British Government, but we shall get it from Jacques Delors. They believe that a good king is better than a bad Parliament. I have never taken that view."[96][97] This argument has also been used by many on the right-wing Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative Party, such as Daniel Hannan MEP.[98] Jonathan Freedland writes in The Guardian that "For [Tony Benn], even benign rule by a monarch was worthless because the king's whim could change and there'd be nothing you could do about it."[99]

Prior to retirement, 1997–2001

In 1997, the Labour Party under Tony Blair won the election. Despite later calling Labour under Tony Blair "the idea of a Conservative group who had taken over Labour"[100] and saying "[Blair] set up a new political party, New Labour",[101] Benn's political diaries Free at Last show that Benn was initially somewhat sympathetic to Blair, welcoming a change of government. Benn supported the introduction of the national minimum wage, and welcomed the progress towards peace and security in Northern Ireland (particularly under Mo Mowlam). He was supportive of the extra public money given to public services in the New Labour years but believed it to be under the guise of privatisation. Overall, his concluding judgement on New Labour is highly critical; he describes its evolution as a way of retaining office by abandoning socialism and distancing the party from the trade union movement,[102] adopting a presidentialist style of politics, overriding the concept of the collective ministerial responsibility by reducing the power of the Cabinet, eliminated any effective influence from the annual conference of the Labour Party and "hinged its foreign policy on support for one of the worst presidents in US history".[103]

Benn strongly objected to the "immoral" bombing of Iraq in December 1998,[104] saying: "Aren't Arabs terrified? Aren't Iraqis terrified? Don't Arab and Iraqi women weep when their children die? Does bombing strengthen their determination? ... Every Member of Parliament tonight who votes for the government motion will be consciously and deliberately accepting the responsibility for the deaths of innocent people if the war begins, as I fear it will."[105]

Several months prior to his retirement, Benn was a signatory to a letter, alongside Niki Adams (Legal Action for Women), Ian Macdonald QC, Gareth Peirce, and other legal professionals, that was published in The Guardian newspaper on 22 February 2001 "condemning" raids of more than 50 brothels in the central London area of Soho. At the time, a police spokesman said: "As far as we know, this is the biggest simultaneous crackdown on brothels and prostitution in this country in recent times", the arrest of 28 people in an operation that involved around 110 police officers.[106] The letter read:

In the name of "protecting" women from trafficking, about 40 women, including a woman from Iraq, were arrested, detained and in some cases summarily removed from Britain. If any of these women have been trafficked ... they deserve protection and resources, not punishment by expulsion. ... Having forced women into destitution, the government first criminalised those who begged. Now it is trying to use prostitution as a way to make deportation of the vulnerable more acceptable. We will not allow such injustice to go unchallenged.[107]

Retirement and final years, 2001–14

Benn did not stand at the 2001 general election, saying he was "leaving parliament in order to spend more time on politics."[108] Along with Edward Heath, Benn was permitted by the Speaker to continue using the House of Commons Library and Members' refreshment facilities. Shortly after his retirement, he became the president of the Stop the War Coalition.[89] He became a leading figure of the British opposition to the War in Afghanistan from 2001 and the Iraq War, and in February 2003 he travelled to Baghdad to meet Saddam Hussein. The interview was shown on British television.[109]

He spoke against the war at the February 2003 protest in London organised by the Stop the War Coalition, with police saying it was the biggest ever demonstration in the UK with about 750,000 marchers, and the organisers estimating nearly a million people participating.[110] In February 2004 and 2008, he was re-elected President of the Stop the War Coalition.[111]

He toured with a one-man stage show and appeared a few times each year in a two-man show with folk singer Roy Bailey. In 2003, his show with Bailey was voted 'Best Live Act' at the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards.[112][113] In 2002 he opened the "Left Field" stage at the Glastonbury Festival. He continued to speak at each subsequent festival; attending one of his speeches was described as a "Glastonbury rite of passage".[114] In October 2003, he was a guest of British Airways on the last scheduled Concorde flight from New York to London. In June 2005, he was a panellist on a special edition of BBC One's Question Time edited entirely by a school-age film crew selected by a BBC competition.[115]

On 21 June 2005, Benn presented a programme on democracy as part of the Channel 5 series Big Ideas That Changed The World. He presented a left-wing view of democracy as the means to pass power from the "wallet to the ballot". He argued that traditional social democratic values were under threat in an increasingly globalised world in which powerful institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the European Commission are unelected and unaccountable to those whose lives they affect daily.[116]

On 27 September 2005, Benn became ill while at the Labour Party Conference in Brighton and was taken by ambulance to the Royal Sussex County Hospital after being treated by paramedics at the Brighton Centre. Benn reportedly fell and struck his head. He was kept in hospital for observation and was described as being in a "comfortable condition".[117] He was subsequently fitted with an artificial pacemaker to help regulate his heartbeat.[118]

In a list compiled by the magazine New Statesman in 2006, he was voted twelfth in the list of "Heroes of our Time". In September 2006, Benn joined the "Time to Go" demonstration in Manchester the day before the start of the final Labour Party Conference with Tony Blair as Party Leader, with the aim of persuading the Labour Government to withdraw troops from Iraq, to refrain from attacking Iran and to reject replacing the Trident missile and submarines with a new system. He spoke to the demonstrators in the rally afterwards.[119] In 2007, he appeared in an extended segment in the Michael Moore film Sicko giving comments about democracy, social responsibility and health care, notably, "If we can find the money to kill people, we can find the money to help people."[120]

A poll by the BBC2 The Daily Politics programme in January 2007 selected Benn as the UK's "Political Hero" with 38% of the vote, beating Margaret Thatcher, who had 35%, by 3%.[121]

In the 2007 Labour Party leadership election, Benn backed the left-wing MP John McDonnell in his unsuccessful bid. In September 2007, Benn called for the government to hold a referendum on the EU Reform Treaty.[122] In October 2007, at the age of 82, and when it appeared that a general election was about to be held, Benn reportedly announced that he wanted to stand, having written to his local Kensington and Chelsea Constituency Labour Party offering himself as a prospective candidate for the seat held by the Conservative Malcolm Rifkind.[123][124] However, there was no election in 2007, and the constituency was subsequently abolished.

In early 2008 Benn appeared on Scottish singer-songwriter Colin MacIntyre's album The Water, reading a poem he had composed himself.[125][126] In September 2008, he appeared on the DVD release for the Doctor Who story The War Machines with a vignette discussing the Post Office Tower; he became the second Labour politician, after Roy Hattersley to appear on a Doctor Who DVD.[127]

Conservatives Daniel Hannan, Douglas Carswell and David Cameron praised Benn in 2008. In their book The Plan, Carswell and Hannan write that "Historically, it was the left that sought to disperse power among the people. ... It was the cause of the Levellers and the Chartists and the Suffragettes, the cause of religious toleration and meritocracy, of the secret ballot and universal education",[128] adding:

These days, though, the radical cause should have different targets. The elites have altered in character and composition. The citizen is far less likely to be impacted by the decisions of dukes or bishops than by those of Nice or his local education authority. The employees of these and similar agencies are, today, the unaccountable crown office-holders against whom earlier generations of radicals would have railed. Yet, with some exceptions – among whom, in a special place of honour, stands Tony Benn – few contemporary British leftists show any interest in dispersing power when doing so would mean challenging public sector monopolies.[128]

Cameron also said in 2008 that, alongside George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, Benn's Arguments for Democracy was "a very powerful book which makes the important point that we vest power in people who are elected, and that we can get rid of, rather than those we can't".[128]

Benn was invited by Richard Branson and Peter Gabriel to join The Elders, an advocacy group comprising Nelson Mandela, Mary Robinson and Jimmy Carter.[129]

At the Stop the War Conference 2009, he described the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as "Imperialist war(s)" and discussed the killing of American and allied troops by Iraqi or foreign insurgents, questioning whether they were in fact freedom fighters, and comparing the insurgents to a British Dad's Army, saying: "If you are invaded you have a right to self-defence, and this idea that people in Iraq and Afghanistan who are resisting the invasion are militant Muslim extremists is a complete bloody lie. I joined Dad's Army when I was sixteen, and if the Germans had arrived, I tell you, I could use a bayonet, a rifle, a revolver, and if I'd seen a German officer having a meal I'd have tossed a grenade through the window. Would I have been a freedom fighter or a terrorist?"[20]

In an interview published in Dartford Living in September 2009, Benn was critical of the Government's decision to delay the findings of the Iraq War Inquiry until after the General Election, stating that "people can take into account what the inquiry has reported on but they’ve deliberately pushed it beyond the election. Government is responsible for explaining what it has done and I don’t think we were told the truth."[130] He also stated that local government was strangled by Margaret Thatcher and had not been liberated by New Labour.[130]

In 2009 Benn was admitted to hospital and An Evening with Tony Benn, scheduled to take place at London's Cadogan Hall, was cancelled. He performed his show, The Writing on the Wall, with Roy Bailey at St Mary's Church, Ashford, Kent, in September 2011, as part of the arts venue's first Revelation St Mary's Season.[131] In July 2011 Benn was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Glamorgan, Wales.[132]

In interviews in 2010 with Amy Goodman on Democracy Now! and 2013 with Afshin Rattansi on RT UK, Benn claimed that the actions of New Labour in the leadup to and aftermath of the Iraq War were such that the former Prime Minister Tony Blair should be tried for war crimes.[133][134] Benn also claimed in 2010 that Blair had lost the "trust of the nation" regarding the war in Iraq.[135]

In November 2011 it was reported that Benn had moved out of his home in Holland Park Avenue, London, into a smaller flat nearby that benefited from a warden.[136] In 2012 Benn was awarded an honorary degree from Goldsmiths, University of London. He was also the honorary president of the Goldsmiths Students' Union, who successfully campaigned for him to retract comments dismissing the Julian Assange rape allegations.[137][138] In February 2013 Benn was among those who gave their support to the People's Assembly in a letter published by The Guardian newspaper.[139] He gave a speech at the People's Assembly Conference held at Westminster Central Hall on 22 June 2013.

In 2013, Tony Benn reiterated his previous opposition to European integration. Speaking to the Oxford Union on the alleged overshadowing of the EU debate by "UKIP and Tory backbenchers", he said:

I took the view that having fought [Europeans in the Second World War] that we should now work with them, and co-operate, and that was my first thought about it. Then how I saw how the European Union was developing, it was very obvious that what they had in mind was not democratic. ... And the way that Europe has developed is that the bankers and the multinational corporations have got very powerful positions, and if you come in on their terms, they will tell you what you can and cannot do. And that is unacceptable. My view about the European Union has always been not that I am hostile to foreigners, but that I am in favour of democracy ... I think they're building an empire there, they want us to be a part of their empire and I don't want that.[140]

Illness and death

In 1990, Benn was diagnosed with chronic lymphatic leukaemia and given three or four years to live; at this time, he kept the news of his leukaemia from everyone except his immediate family. Benn said: "When you're in parliament, you can't describe your medical condition. People immediately start wondering what your majority is and when there will be a by-election. They're very brutal."[141] This was revealed in 2002 with the release of his 1990–2001 diaries.[141]

Benn suffered a stroke in 2012, and spent much of the following year in hospital.[142] He was reported to be "seriously ill" in hospital in February 2014.[143] Benn died at home, surrounded by his family, on 14 March 2014, at age 88.[144][145]

Benn's funeral took place on 27 March 2014 at St Margaret's Church, Westminster.[146][147] His body had lain in rest at St Mary Undercroft in the Palace of Westminster the night before the funeral service.[148] The service ended with the singing of "The Red Flag".[149] His body was then cremated; the ashes are expected to be buried alongside those of his wife at the family home near Steeple, Essex.[150]

Figures from across the political spectrum praised Benn following his death,[151] and the leaders of all three major political parties (the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats) in the United Kingdom paid tributes to Benn on his death.

David Cameron (Conservative leader and Prime Minister) said:

... he was an extraordinary man: a great writer, a brilliant speaker, extraordinary in Parliament, and a great life of public and political and parliamentary service. I mean, I disagreed with most of what he said. But he was always engaging and interesting, and you were never bored when reading or listening to him, and the country a great campaigner, a great writer, and someone who I'm sure whose words will be followed keenly for many, many years to come.[152][153]

Deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg called Benn a "astonishing, iconic figure" and a "veteran parliamentarian, he was a great writer, he had great warmth and he had great conviction ... his political life will be looked back on with affection and admiration".[153]

Leader of the Opposition and Labour leader Ed Miliband, who knew Benn personally as a family friend, said:

I think Tony Benn will be remembered as a champion of the powerless, as a conviction politician, as somebody of deep principle and integrity. The thing about Tony Benn is that you always knew what he stood for, and who he stood up for. And I think that's why he was admired right across the political spectrum. There are people who agreed with him and disagreed with him, including in my own party, but I think people admired that sense of conviction and integrity that shone through from Tony Benn.[152][153]

Diaries and biographies

Benn was a prolific diarist: nine volumes of his diaries have been published. The final volume was published in 2013.[154] Collections of his speeches and writings were published as Arguments for Socialism (1979), Arguments for Democracy (1981), (both edited by Chris Mullin), Fighting Back (1988) and (with Andrew Hood) Common Sense (1993), as well as Free Radical: New Century Essays (2004). In August 2003, London DJ Charles Bailey created an album of Benn's speeches (ISBN 1-904734-03-0) set to ambient groove.

He made public several episodes of audio diaries he made during his time in Parliament and after retirement, entitled The Benn Tapes, broadcast originally on BBC Radio 4. Short series have been played periodically on BBC Radio 4 Extra.[155] A major biography was written by Jad Adams and published by Macmillan in 1992; it was updated to cover the intervening 20 years and reissued by Biteback Publishing in 2011: Tony Benn: A Biography (ISBN 0-333-52558-2). A more recent "semi-authorised" biography with a foreword by Benn was published in 2001: David Powell, Tony Benn: A Political Life, Continuum Books (ISBN 978-0826464156). An autobiography, Dare to be a Daniel: Then and Now, Hutchinson (ISBN 978-0099471530), was published in 2004.

There are substantial essays on Benn in the Dictionary of Labour Biography by Phillip Whitehead, Greg Rosen (eds), Politicos Publishing, 2001 (ISBN 978-1902301181) and in Labour Forces: From Ernie Bevin to Gordon Brown, Kevin Jefferys (ed.), I.B. Tauris Publishing, 2002 (ISBN 978-1860647437). Michael Moore dedicates his book Mike's Election Guide 2008 (ISBN 978-0141039817) to Benn, with the words: "For Tony Benn, keep teaching us".[156]

Plaques

During his final years in Parliament, Benn placed three plaques within the Houses of Parliament. Two are in a room between the Central Lobby and Strangers' Gallery that holds a permanent display about the suffragettes.[157] The first was placed in 1995. The second was placed in 1996 and is dedicated to all who work within the Houses of Parliament.

The third is dedicated to Suffragette Emily Wilding Davison and was placed in the broom cupboard next to the Undercroft Chapel within the Palace of Westminster, where Davison is said to have hidden during the 1911 census in order to establish her address as the House of Commons.[158][159]

In 2011 Benn unveiled a plaque in Highbury, North London, to commemorate the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.[160]

Legacy

In Bristol, where Benn first served as a Member of Parliament, a number of tributes exist in his honour. A bust of him was unveiled in Bristol's City Hall in 2005.[161][162] In 2012 Transport House on Victoria Street, headquarters of Unite the Union's regional office, was officially renamed Tony Benn House and opened by Benn himself.[163] As of 2015 he appears, alongside other famous people associated with the city, on the reverse of the Bristol Pound's £B5 banknote.[164]

Benn told the Socialist Review in 2007 that:

I'd like to have on my gravestone: "He encouraged us." I'm proud to have been in the parliament that introduced the health service, the welfare state and voted against means testing. I did my maiden speech on nationalising the steel industry, put down the first motion for the boycott of South African goods, and resigned from the shadow cabinet in 1958 because of their support for nuclear weapons.

I think you do plant a few acorns, and I have lived to see one or two trees growing: gay rights, freedom of information, CND. I'm not claiming them for myself but you feel you have encouraged other people and see the arguments developing.

I'm not ashamed of making mistakes. I've made a million mistakes and they're all in the diary. When we edit the diary – which is cut to around 10 percent – every mistake has to be printed because people look to see if you do. I would be ashamed if I thought I'd ever said anything I didn't believe to get on, but making mistakes is part of life, isn't it?[165]

Styles

- Anthony Wedgwood Benn, Esq. (1925 – 12 January 1942)

- The Hon. Anthony Wedgwood Benn (12 January 1942 – 30 November 1950)

- The Hon. Anthony Wedgwood Benn, MP (30 November 1950 – 17 November 1960)

- The Rt Hon. the Viscount Stansgate (17 November 1960 – 31 July 1963)

- Anthony Wedgwood Benn, Esq. (31 July – 20 August 1963)

- Anthony Wedgwood Benn, Esq., MP (20 August 1963 – 1964)

- The Rt Hon. Anthony Wedgwood Benn, MP (1964 – October 1973)

- The Rt Hon. Tony Benn, MP (October 1973 – 9 June 1983)

- The Rt Hon. Tony Benn (9 June 1983 – 1 March 1984)

- The Rt Hon. Tony Benn, MP (1 March 1984 – 7 June 2001)

- The Rt Hon. Tony Benn (7 June 2001 – 14 March 2014)

Bibliography

- Speeches, Spokesman Books (1974); ISBN 0851240917

- Levellers and the English Democratic Tradition, Spokesman Books (1976); ISBN 978-0-85124-633-8

- Why America Needs Democratic Socialism, Spokesman Books (1978); ISBN 978-0-85124-266-8

- Prospects, Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers, Technical, Administrative and Supervisory Section (1979)

- Case for Constitutional Civil Service, Institute for Workers' Control (1980); ISBN 978-0-901740-67-0

- Case for Party Democracy, Institute for Workers' Control (1980); ISBN 978-0-901740-70-0

- Arguments for Socialism, Penguin Books (1980); ISBN 978-0-14-005489-7

- & Chris Mullin, Arguments for Democracy, Jonathan Cape (1981); ISBN 978-0-224-01878-4

- European Unity: A New Perspective, Spokesman Books (1981) ISBN 978-0-85124-326-9

- Parliament and Power: Agenda for a Free Society, Verso Books (1982); ISBN 978-0-86091-057-2

- & Andrew Hood, Common Sense: New Constitution for Britain, Hutchinson (1993)

- Free Radical: New Century Essays, Continuum International Publishing (2004); ISBN 978-0-8264-7400-1

- Dare to Be a Daniel: Then and Now, Hutchinson (2004); ISBN 978-0-09-179999-1

- Letters to my Grandchildren: Thoughts on the Future, Arrow Books (2010); ISBN 978-0-09-953909-4

Diaries

- Years of Hope: Diaries 1940–62, Hutchinson (1994); ISBN 978-0-09-178534-5

- Out of the Wilderness: Diaries 1963–67, Hutchinson (1987); ISBN 978-0-09-170660-9

- Office Without Power: Diaries 1968–72, Hutchinson (1988); ISBN 978-0-09-173647-7

- Against the Tide: Diaries 1973–76, Hutchinson (1989); ISBN 978-0-09-173775-7

- Conflicts of Interest: Diaries 1977–80, Hutchinson (1990); ISBN 978-0-09-174321-5

- The End of an Era: Diaries 1980–90, Hutchinson (1992); ISBN 978-0-09-174857-9

- The Benn Diaries: Single Volume Edition 1940–90, Hutchinson (1995); ISBN 978-0-09-179223-7

- Free at Last!: Diaries 1991–2001, Hutchinson (2002); ISBN 978-0-09-179352-4

- More Time for Politics: Diaries 2001–2007, Hutchinson (2007); ISBN 978-0-09-951705-4

- A Blaze of Autumn Sunshine: The Last Diaries, Hutchinson (2013); ISBN 978-0-09-194387-5

See also

References

- ^ "Moderate":

- White, Michael (14 March 2014). "Tony Benn: the establishment insider turned leftwing outsider". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- Duncan Hall. A2 Government and Politics: Ideologies and Ideologies in Action. Lulu.com. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4477-3399-7.

- ^ a b Re Parliamentary Election for Bristol South East [1964] 2 Q.B. 257, [1961] 3 W.L.R. 577

- ^ "British socialist Tony Benn dead at 88". News.com.au. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Renton, Dave (February 1997). "Does Labour's Left Have an Alternative?". Socialist Review. Archived from the original on 11 September 2003. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Collection – The Rt Hon Tony Benn MP". Art in Parliament. UK Parliament. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Burrows, Saffron (21 December 2014). "He loved so well: a moving tribute to Tony Benn by the actor Saffron Burrows". The Guardian. Stop the War Coalition. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "Tony Benn – Official Website". tonybenn.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2003. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hale, Leslie; Potter, Mark (January 2008). "Benn, William Wedgwood". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Benn, Tony (2003). Free Radical. Continuum. p. 226. ISBN 0-8264-6596-X.

- ^ a b Tony Benn on Jesus (YouTube video). YouTube. Channel 4.

- ^ Sydney Higgins (1984). The Benn Inheritance: The Story of a Radical Family. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-78524-8. Quoted in Brown, Rob (27 September 1984). "Vital key to the real Tony Benn". The Glasgow Herald. p. 8. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ Kenny, Mary (14 March 2014). "Tony Benn 1925–2014: a politician shaped by Christianity". The Catholic Herald. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Wilby, Peter (27 March 2014). "Tony Benn's banana diet, lapsed Christians and ignoring no smoking signs". New Statesman. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Tony Benn (2 July 2015). The Best of Benn. Cornerstone. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-78475-032-9.

- ^ Wilby, Peter (22 March 2014). "Tony Benn: Peter Wilby reads the diaries". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Brodie, Marc (January 2008). "Benn, Sir John Williams". Oxford National Dictionary of Biography Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Stearn, Roger T. (2004). "Benn, Margaret Eadie Wedgwood". Oxford National Dictionary of Biography Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Engel, Matthew (14 March 2014). "The paradox of Tony Benn". Financial Times. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ McSmith, Andy; Dalyell, Tam (14 March 2014). "Tony Benn obituary: Politician who embodied the soul of the Labour Party and came to be admired – even by his rivals". The Independent. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ a b Jesse Oldershaw (camera); Andy Cousins (editor) (25 April 2009). Tony Benn – Stop the War Conference 2009. Stop the War Coalition. Event occurs at 3:06.

- ^ A fuller transcript of that speech, in which he called the Home Guard "Dad's Army", is given in the section "Retirement and final years".

- ^ "Tony Benn". The Biography Channel. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "No. 37124". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 8 June 1945. - ^ Raymond Clark (1 October 2013). To the End, They Remain: Thoughts on War, Peace and Reconciliation. History Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7509-5308-5.

- ^ "No. 37327". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 26 October 1945. - ^ a b c d e f Alwyn W. Turner (19 March 2009). Crisis? What Crisis?: Britain in the 1970s. Aurum Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-1-84513-851-6.

- ^ "Mr Benn wipes away his past". The Times Diary. Times Newspapers. 18 March 1976.

- ^ "Not Out". The Times. Diary. 4 April 1977.

- ^ Dominic Sandbrook (19 April 2012). Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974–1979. Penguin Books Limited. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-84614-627-5.

- ^ Tabassum, Nazir. "Opening Speach of Prof. Nazir Tabassum". Progressive Writers Conference. South Asian Peoples Forum UK. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ Benn, Tony (2012). Speeches ([New] ed. ed.). Nottingham: Spokesman Books. ISBN 9780851248103. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ "Caroline Benn". Daily Telegraph. London, UK: Telegraph Media Group. 24 November 2000. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Skinitis, Alexia (10 January 2009). "Emily Benn the younger". Times Online. London, UK: Times Newspapers. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Benn's granddaughter runs for MP". BBC News. 25 September 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ French, Philip (26 July 2009). "Philip French's screenlegends: Margaret Rutherford". The Observer. London, UK. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Tony Benn: making mistakes is part of life", The Daily Telegraph, 12 August 2009.

- ^ "Tony Benn: You Ask The Questions", The Independent, 5 June 2006.

- ^ "The Benn dynasty". BBC News. 11 June 1999. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "New Members Sworn". Hansard. House of Commons. 4 December 1950. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "New Members Sworn". Hansard. House of Commons. 5 December 1950. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b c "Profile: Tony Benn". BBC Bristol. 4 April 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "How we organised to break racism on Bristol buses". Socialist Worker. No. 2374. Socialist Workers Party. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Jon (27 August 2013). "What was behind the Bristol bus boycott?". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ Tony Benn and Peter Kellner "Tony Benn's Finest Speech", The Huffington Post, 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Peerage Act 1963". Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Jad Adams, Tony Benn: A Biography (MacMillan 1992) ISBN 978-1849540964 at pages 203–4, e.g., Viscount Hinchingbrooke, and Lords Hogg and Douglas-Home.

- ^ "No. 43072". The London Gazette. 2 August 1963.

- ^ "Tony Benn dies: his most memorable quotes". The Telegraph. 14 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Five lesser-spotted things Tony Benn gave the UK". BBC News. Magazine Monitor: A collection of cultural artefacts. 14 March 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Asa Briggs, The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom: Volume V: Competition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 515–19, 540.

- ^ "Wireless and Television (Pirate Stations)", Hansard, HC Deb, vol. 730 cc858-70, 22 June 1966.

- ^ "Marine, & C., Broadcasting (Offences)", HC Deb 27 July 1966, Hansard, vol. 732 c1720.

- ^ "UK Confidential Transcripts: Tony Benn – The Labour Minister". BBC News. 1 January 2002. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b c David Butler; Michael Pinto-Duschinsky (2 July 1971). British General Election of 1970. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-1-349-01095-0.

- ^ Benn, Tony (31 January 2013). The Benn Diaries: 1940–1990. Random House. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-4464-9373-1.

- ^ "Racist Laws 1971" Black History Walks (YouTube)

- ^ Duncan Watts; Colin Pilkington (29 November 2005). Britain in the European Union Today: Third Edition. Manchester University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-7190-7179-9.

- ^ Alistair Jones (2007). Britain and the European Union. Edinburgh University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-7486-2428-7.

- ^ Butler, David; Kavanagh, Dennis (1974). The British General Election of February 1974. Macmillan. p. 20. ISBN 0333172973.

- ^ Hird, Christopher (December 1981). "The Crippled Giants". New Internationalist. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ Benn, Tony (1995). The Benn Diaries. Arrow. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-09-963411-9.

- ^ Benn, Tony (31 January 2013). The Benn Diaries: 1940–1990. Random House. p. 367. ISBN 978-1-4464-9373-1.

- ^ Hoggart, Simon (18 October 2013). "Simon Hoggart's week: the honour of being loathed". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Bagley, Richard (1 May 2014). "Into The Archives: Tony Benn On The True Power Of Democracy". The Morning Star. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Powell, David (2003). Tony Benn: a political life (2 ed.). London & New York: Continuum. pp. 82, 84. ISBN 0-8264-7074-2.

- ^ Benn, Tony (1988). Out of the Wilderness: Diaries 1963–67. Arrow. p. xi–xiii. ISBN 978-0-09-958670-8.

- ^ Benn, Tony (1988). Out of the Wilderness: Diaries 1963–67. p. xiii.

- ^ Kavanagh, Dennis (1990). "Tony Benn: Nuisance or Conscience?". In Kavanagh, Dennis (ed.). Politics and Personalities. p. 184.

- ^ Gardiner, George (7 May 1978). "Are these MPs TRYING to do the Kremlin's dirty work?" (PDF). The Sunday Express. p. 16. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Matthews, Nick (14 April 2014). "Benn, co-ops and workplace democracy". The Morning Star. p. 20. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Kavanagh, Dennis (1990). "Tony Benn: Nuisance or Conscience?". In Kavanagh, Dennis (ed.). Politics and Personalities. Macmillan. p. 78.

- ^ Warden, John (13 June 1974). "Heath broadside for 'Commissar Benn'". The Glasgow Herald.

- ^ Whiteley, Paul; Gordon, Ian (11 January 1980). "The Labour Party: Middle Class, Militant and Male". New Statesman: 41–42.

- ^ "Benn's call for SF to take seats". BBC News Online. 12 May 2005. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Peterkin, Tom (18 August 2012). "Scottish independence: Tony Benn: 'UK split would divide me with a knife'". The Scotsman. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Emery, Fred (30 September 1980). "Mr Benn proposes timetable of one month to abolish Lords and leave EEC". The Times, archived by Gale Group. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Peter Childs; Michael Storry (13 May 2013). Encyclopedia of Contemporary British Culture. Routledge. p. 485. ISBN 1-134-75555-4.

- ^ Donald Sassoon (30 July 2010). One Hundred Years of Socialism: The West European Left in the Twentieth Century. I.B.Tauris. p. 698. ISBN 978-0-85771-530-2.

- ^ Gerald M. Pomper (1988). Voters, Elections, and Parties: The Practice of Democratic Theory. Transaction Publishers. p. 375. ISBN 978-1-4128-4112-2.

- ^ Seyd, Patrick (1987). The Rise and Fall of the Labour Left. Macmillan Education. p. 165. ISBN 0-333-44748-4.

- ^ "House of Commons Statement: Falkland Islands". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. 15 June 1982. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "Benn on the couch". The Sun. News international. 1 March 1984.

- ^ "Labour's new line-up". The Times. archived by Gale Group. 3 November 1983. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chapter 06; ...1974 strike...a conversation with miners...Labour government... Benn helps divide miners..." libcom.org. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Robertson, Jack (23 April 2010). "25 years after the Great Miners' Strike". International Socialism (126). London, UK: Socialist Workers Party. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Militant Video: Wembley Conference Centre 1984 (YouTube video). YouTube. Militant. 20 October 1984.

- ^ Charlton, Corey (26 December 2014). "What the KGB thought of cabinet minister Tony Benn". Mail Online. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "Miners' Amnesty (General Pardon)". Hansard. House of Commons. 28 June 1985. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b Stadlen, Nick (8 December 2006). "Brief Encounter: Tony Benn". The Guardian. London, UK: Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Hearse, Phil (15 March 2014). "Tony Benn: A Vision to Inspire and Mobilise". Socialist Resistance. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

He readily took up the banner of LGBT struggles, what was then known as lesbian and gay liberation.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Scott (14 March 2014). "Tony Benn: "Long before it was accepted I did support gay rights"". Pink News. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Hansard, HC Deb (22 November 1990) vol 181, cols 439–518, at 486

- ^ "Commonwealth of Britain Bill". Hansard. House of Commons. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Benn, Tony; Hood, Andrew (17 June 1993). Hood, Andrew (ed.). Common Sense: New Constitution for Britain. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-177308-3.

- ^ Alan Taylor (2009). Those who Marched Away: An Anthology of the World's Greatest War Diaries. Canongate. p. 601. ISBN 978-1-84767-415-9.

- ^ "Column 333". Hansard, House of Commons. 20 November 1991. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Brian MacArthur (3 May 2012). The Penguin Book of Modern Speeches. Penguin Books Limited. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-14-190916-5.

- ^ Daniel Hannan (24 March 2016). Why Vote Leave. Head of Zeus. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-78497-709-2.

- ^ Freedland, Jonathan (9 October 2015). "EU referendum: the next big populist wave could sweep Britain out of Europe". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Delaney, Sam (14 March 2014). "Tony Benn interview: "Labour suffered greatly through Tony Blair"". Big Issue. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Benn, Tony (4 September 2010). "Tony Benn: 'What is really significant about Tony Blair was that he set up a new political party, New Labour'". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Mortimer, Jim (20 November 2002). "Tony Benn: An inspiring symbol of political steadfastness and advocacy" (PDF). Morning Star. p. 9. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Mortimer, Jim (6 May 2003). "Telling it straight" (PDF). Morning Star. p. 8. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tony Benn dies: watch archive clip of Labour stalwart in Parliament". The Daily Telegraph. 14 March 2014.

- ^ Allegretti, Aubrey (3 December 2015). "If Tony Benn Were Here Today, He Might Use This Iraq Speech To Defend Not Bombing Syria". The Huffington Post UK. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ "50 Soho brothels targeted in raids". Herald Scotland. 16 February 2001. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Niki Adams; Tony Benn; et al. (22 February 2001). "Law violates sex workers". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Younge, Gary (20 July 2002). "The stirrer". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Full text of Benn interview with Saddam". BBC News. 4 February 2003. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ "'Million' march against Iraq war". BBC News. 16 February 2003. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ "Elected positions". Stop the War Coalition. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Irwin, Colin (31 January 2013). "BBC Radio 2 Folk awards 2013 names Nic Jones singer of the year". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ "Radio 2 Folk Awards 2003". Press Office. BBC. 11 February 2003.

- ^ Jonze, Tim (24 June 2007). "Glastonbury festival: Tony Benn on 'a self-generating community'". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Question Time: A question of citizenship". BBC News. 1 July 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Joseph, Joe (22 June 2005). "Benn's stall sells democracy short". The Times. p. 27.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff (28 September 2005). "Tony Benn 'comfortable' in hospital after fall". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ "Benn gets pacemaker after fall". BBC News. 1 October 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ "Thousands at city's anti-war demo". BBC News. 23 September 2006. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ James Walsh (15 March 2014). "10 of the best Tony Benn quotes – as picked by our readers". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ "The Magnificent Seven political heroes..." BBC News. 12 December 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "Give us EU referendum, says Benn". BBC News. 24 September 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "I want to be an MP again – Benn". BBC News. 4 October 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Attewill, Fred (4 October 2007). "Benn: I want to return to parliament". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ "Tony Benn, pop star". The Daily Telegraph. 7 February 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "House music: Tony Benn's debut solo album". The Independent. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Wilkins, Jonathan (21 August 2008). "Doctor Who: The War Machines Review". Total SciFi Online. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Sparrow, Andrew (18 September 2009). "Cameron joins Daniel Hannan in Tony Benn fan club". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "Going out in a blaze of anger: The almost unbearably moving diaries of a Labour contrarian". Mail Online. 2 November 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ a b Khairoun, Abdel (September 2009). "Big Benn Chimes in to Dartford" (PDF). Dartford Living. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Clive Conway Celebrity Productions – An Audience with an Evening With Tony Benn". celebrityproductions.info. 2011. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2016 – via the Wayback Machine.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "University of Glamorgan honours contributions to public life, communities, science, literature, and sport". news.glam.ac.uk. 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ Goodman, Amy; Benn, Tony (21 September 2010). "Tony Benn on Tony Blair: "He Will Have to Live 'Til the Day He Dies with the Knowledge that He Is Guilty of a War Crime"". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ Rattansi, Afshin; Benn, Tony (16 December 2013). "Big Benn: Blair committed war crimes in Iraq". RT International. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Labour drückt sich vor Irak-Debatte" [Labour shirks Iraq debate]. Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). 11 May 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

Der Veteran der Labour-Linken, Tony Benn, sagte, der Irak-Krieg habe Blair das "Vertrauen der Nation" gekostet.

- ^ Richard Kay "Frail Tony Benn downsizes to £750,000 flat (well, his house was worth £3m)", Daily Mail, 1 November 2011; retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Goldsmiths academics pay tribute to Tony Benn". Goldsmiths, University of London. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ "Benn sorry for dismissing Assange rape allegations". Liberal Conspiracy. 18 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ People's Assembly opening letter, The Guardian, 5 February 2013.

- ^ Tony Benn (25 March 2013). European Union. Oxford Union.

- ^ a b "Tony Benn: My fight with leukaemia". The Scotsman. 29 September 2002. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "Tony Benn, veteran Labour politician, dies aged 88". The Guardian. 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Tony Benn seriously ill in hospital", BBC News, 12 February 2014.

- ^ "BBC News – Labour stalwart Tony Benn dies at 88". BBC Online. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Steve (14 March 2004). "Tony Benn dead: Veteran Labour politician passes away aged 88". The Independent. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Tony Benn's funeral takes place in Westminster". BBC. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ Owen Jones (27 March 2014). "Bedfellows and foes unite at Tony Benn's funeral". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Queen approves Tony Benn overnight vigil in Parliament's chapel". BBC. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Tony Benn's funeral ends with rendition of The Red Flag". Daily Telegraph. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ William Watkinson (27 March 2014). "Tony Benn funeral: Crowds gather for Westminster send-off". Essex Chronicle. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ Dominiczak, Peter; Swinford, Steve (14 March 2014). "'I hope I didn't cause offence': Tony Benn's message from beyond the grave". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b "David Cameron and Ed Miliband pay tribute to Tony Benn – video". The Guardian. ITN. 14 March 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Tributes to former MP Tony Benn from key politicians". BBC News Online. 14 March 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ "Happy Birthday Tony Benn, 87", The Times, 3 April 2012.

- ^ "BBC Radio 7 Programmes – The Benn Tapes". BBC. 16 March 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Goodman, Amy (1 November 2008). "Michael Moore on the Election, the Bailout, Healthcare, and 10 Proposals for the Next President by Michael Moore". Democracy Now!. ZCommunications. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2010 – via the Wayback Machine.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Suffragettes display". www.parliament.uk. UK Parliament. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "Benn's secret tribute to suffragette martyr". BBC News. 17 March 1999. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ "Plaque to Emily Wilding Davison". www.parliament.uk. Uk Parliament. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "Tony Benn to unveil Islington People's Plaque commemorating the Peasants' Revolt". Islington Borough Council. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ "Bust celebrates politician's work". BBC News. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Tony Benn remembered 1925 – 2014". Bristol Post.

- ^ "Former Bristol Labour MP Tony Benn opens union HQ". BBC News. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "New Bristol Pounds". Bristol Pound. Retrieved 4 July 2015.