Earl of Devon

| Earldom of Devon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Creation date | 3 September 1553 |

| Creation | Fifth |

| Created by | Mary I of England |

| Peerage | Peerage of England |

| First holder | Edward Courtenay |

| Present holder | Charles Courtenay, 19th Earl of Devon |

| Heir apparent | Jack Courtenay, Lord Courtenay |

| Remainder to | 1st Earl's heirs male whatsoever |

| Subsidiary titles | Baronet, of Powderham Castle |

| Seat(s) | Powderham Castle |

| Former seat(s) | Tiverton Castle Colcombe Castle |

| Motto | 1st: QUOD VERUM TUTUM (What is true is safe) 2nd: UBI LAPSUS QUID FECI (Where I have fallen, what have I done?) |

Earl of Devon is a title that has been created several times in the Peerage of England. It was possessed first (after the Norman Conquest of 1066) by the Redvers family (alias de Reviers, Revieres, etc.), and later by the Courtenay family. It is not to be confused with the title of Earl of Devonshire, which is held by the Duke of Devonshire, although the letters patent for the creation of the latter peerages used the same Latin words, Comes Devon(iae).[1] It was a re-invention, if not an actual continuation, of the pre-Conquest office of Ealdorman of Devon.[2]

Close kinsmen and powerful allies of the Plantagenet kings, especially Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V, the Earls of Devon were treated with suspicion by the Tudors, perhaps unfairly, partly because William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475–1511), had married Princess Catherine of York, a younger daughter of King Edward IV, bringing the Earls of Devon very close to the line of succession to the English throne. During the Tudor period, all but the last Earl were attainted, and there were several recreations and restorations. The last recreation was to the heirs male of the grantee, not (as would be usual) to the heirs male of his body. When he died unmarried, it was assumed the title was extinct, but a much later very distant Courtenay cousin, of the family seated at Powderham, whose common ancestor was Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (d.1377), seven generations before this Earl, successfully claimed the title in 1831. During this period of dormancy, the de jure Earls of Devon, the Courtenays of Powderham, were created baronets and later viscounts.

During this time, an unrelated earldom of a similar name, now called for distinction the Earldom of Devonshire, was created twice, once for Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy, who had no legitimate children, and a second time for the Cavendish family, now Dukes of Devonshire. Unlike the Dukes of Devonshire, seated in Derbyshire, the Earls of Devon were strongly connected to the county of Devon. Their seat is Powderham Castle, near Starcross on the River Exe.

The Earl of Devon has not inherited the ancient and original Barony of Courtenay or the Viscountcy of Courtenay of Powderham (1762–1835); nevertheless, his heir is styled Lord Courtenay by courtesy.

Ealdormen of Devon

[edit]Before the Norman Conquest of 1066, the highest sub-regal authority in Devon was the Ealdorman, of which office the later Earldom of Devon was a re-invention, if not an actual continuation.[3]

- Odda, under Alfred the Great, led Anglo-Saxon forces in the Battle of Cynwit, ultimately defeating an army led by Viking chieftain Ubba.

- Ordgar (d.971), under King Edgar (ruled 959–975). He founded Tavistock Abbey in 961. His son was Ordwulf (died after 1005), who realised the founding.[4]

The post-Norman earldom

[edit]The first Earl of Devon was Baldwin de Redvers (c. 1095–1155), son of Richard de Redvers (d.1107), feudal baron of Plympton, Devon, one of the principal supporters of King Henry I (1100–1135).[5][6][7] It was believed by some that Richard de Redvers had in fact been created the first Earl of Devon, and although in the past this caused confusion concerning the numerical ordering of the Earls of Devon, the point is now more clearly settled in favour of Baldwin as the first.[8] Baldwin de Redvers was a great noble in Devon and the Isle of Wight, where his seat was Carisbrooke Castle, and was one of the first to rebel against King Stephen (1135–1154). He seized Exeter Castle, and mounted naval raids from Carisbrooke, but was driven out of England to Anjou, France, where he joined the Empress Matilda. She created him Earl of Devon after she established herself in England, probably in early 1141.

Baldwin de Redvers, 1st Earl of Devon, was succeeded by his son, Richard de Redvers, 2nd Earl of Devon, and grandson, Baldwin de Redvers, 3rd Earl of Devon, and the latter was succeeded by his brother, Richard de Redvers, 4th Earl of Devon, who died childless.[9][10][11]

William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon (d.1217) was the third son of Baldwin, the 1st Earl.[12] He had only two children who left children. His son Baldwin died on 1 September 1216 at the age of sixteen, leaving his wife Margaret pregnant with Baldwin de Redvers, 6th Earl of Devon. King John (1199–1216) forced her to marry Falkes de Breauté, but she was rescued at the fall of Bedford Castle in 1224 and divorced from him, as having been in no true marriage. She is thus called Countess of Devon in several records. The fifth Earl's youngest daughter, Mary de Redvers, known as 'de Vernon', was eventually the sole heiress of the 1141 Earldom. She married firstly, Pierre de Preaux, and secondly, Robert de Courtenay (d.1242), feudal baron of Okehampton, Devon.[13]

The 6th Earl was succeeded by his son, Baldwin de Redvers, 7th Earl of Devon (d.1262), who died without children.[14][15] His sister, Isabel de Forz, widow of William de Forz, 4th Earl of Albemarle, became Countess of Devon suo jure.[16] Her children predeceased her and she had no grandchildren.

Her lands were inherited by her second cousin once removed, Hugh de Courtenay (1276–1340), feudal baron of Okehampton, the great-grandson of Mary de Redvers and Robert de Courtenay (d.1242) of Okehampton.[17] He descended from Renaud de Courtenay, anglicised to Reginald I de Courtenay, of Sutton, a French nobleman of the House of Courtenay who took up residence in England after the conquest and founded the English branch of the Courtenay family, who became Earls of Devon in 1335. The title is still held today, by his direct male descendant.

Hugh de Courtenay was summoned by writ to Parliament in 1299 as Hugo de Curtenay, whereby he is held to have become Baron Courtenay.[18][19] However, forty-one years after the death of Isabella de Fortibus, Countess of Devon|Isabel de Forz, letters patent were issued on 22 February 1335 declaring him Earl of Devon, and stating that he "should assume such title and style as his ancestors, Earls of Devon, had wont to do", by which he was confirmed as Earl of Devon.[20] Although some sources consider this a new grant the wording of the grant arguably indicates a confirmation and that he became thereby 9th Earl. Historic sources thus variously refer to him as either 1st Earl or 9th Earl, and the position cannot be decided either way due to the uncertainty of the surviving evidence. For the last years of his life he thus held two titles, 1st/9th Earl of Devon, by reason of the 1335 letters patent, and 1st Baron Courtenay, the title by which he had been summoned to Parliament in the years prior to the 1335 letters patent.[21]

The 1st/9th Earl was succeeded by his son, Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd/10th Earl of Devon.[22] Three of the eight sons of the 2nd/10th Earl had descendants; a fourth, William Courtenay, was Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor. Sir Hugh Courtenay (1326–1349), KG, eldest son and heir of the 2nd/10th Earl, was one of the founding members of the Order of the Garter, but both he and his only son, Sir Hugh Courtenay (died 1374), predeceased the 2nd/10th Earl.[23] Sir Edward de Courtenay (died 1368/71), the third son, also predeceased his father, but left an eldest son, Edward de Courtenay, 3rd Earl of Devon (1357–1419), "The Blind", who inherited as the 3rd/11th Earl.[24] The 3rd/11th Earl's eldest son, Sir Edward Courtenay (died 1418), married Eleanor Mortimer, daughter of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, but predeceased his father, leaving no children, and the 3rd/11th Earl's second son, Hugh de Courtenay, 4th Earl of Devon (d.1422) succeeded him as became 4th/12th Earl of Devon.[25][26] The 4th/12th Earl was succeeded by his son, Thomas Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (d.1458).[27]

The Wars of the Roses were disastrous for the Courtenay earls. The 5th/13th Earl's son, Thomas Courtenay, 6th/14th Earl of Devon (d.1461), fought on the losing Lancastrian side at the Battle of Towton (1461), was captured and beheaded, and all his honours forfeited by attainder. Tiverton Castle and all the other vast Courtenay lands were forfeited to the crown, later to be partially restored.

Second creation, 1469

[edit]Edward IV had made Humphrey Stafford, grandson and heir of Humphrey Stafford of Hooke, Dorset, his agent in the West Country.[28] On 17 May 1469, Stafford was created Earl of Devon, but was killed only three months later, having led royal forces against the rebel army of Robin of Redesdale, a deputy of the Earl of Warwick. Captured in the Battle of Edgecote, he was beheaded at Bridgwater on 17 August 1469. He left no children, and with his death the second creation of the earldom became extinct. He is known as the "Three Months' Earl".

Restored first creation, 1470

[edit]The Wars of the Roses continued and in 1470 the Lancastrian forces under Warwick prevailed, and Henry VI was restored to the throne. The 1461 attainders were reversed, and the earldom of Devon was restored to John Courtenay, 7th/15th Earl of Devon (d.1471), youngest brother of Thomas, the 6th/14th Earl.[29] There had been a middle brother also, Henry Courtenay (d.1469), who also perished in the Wars. When the Yorkists again prevailed in the following year, Edward IV had the legislation of Henry VI's second reign cancelled, and all of John Courtenay's honours were forfeited. A few weeks later, on 4 May 1471, he died fighting on the losing side at the Battle of Tewkesbury (1471), leaving no children. According to Cokayne, "on his death the representation of the ancient Earls of Devon (of the family of Reviers from whom the Courtenays had inherited it) and of the Barony of Courtenay (created by the writ of 1299) fell into abeyance between his sisters or their descendants, subject to the attainder of Edward IV (1461), which revived on that King's re-accession 14 April 1471".[30]

Third creation, 1485

[edit]

Sir Edward Courtenay (d.1509), great-nephew of the 3rd/11th Earl, fought on the winning side at Bosworth on 22 August 1485, ending the Wars of the Roses and two months later the new King, Henry VII (1485–1509), by letters patent dated 16 October 1485, created Edward Courtenay Earl of Devon (or Devonshire), with the usual remainder to the heirs male of his body.[31] As the son and heir of Sir Hugh Courtenay (died 1471/2) of Bocconoc, Sir Edward Courtenay was the heir male of his family, his father being the son and heir of Sir Hugh Courtenay of Haccombe, younger brother of Edward de Courtenay, 3rd/11th Earl of Devon (d.1419), "The Blind". He united the Tiverton and Powderham lines of the family, having married Elizabeth Courtenay, a daughter of a younger son of the Powderham line. He died 28 May 1509, when the earldom was forfeited by the attainder in 1504 of his son and heir, William Courtenay (d.1511).

Fourth creation, 1511

[edit]William Courtenay (d.1511) had married Princess Catherine of York, a younger daughter of King Edward IV, and was thus brother-in-law to Elizabeth of York but nonetheless Elizabeth's husband Henry VII had Courtenay imprisoned and attainted for his supposed, but unproven, complicity in the conspiracy of Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk. However, during the reign of his son and successor King Henry VIII (1509–1547) William Courtenay was gradually forgiven. His lands were restored as far as was possible, and by letters patent of 10 May 1511, he was created Earl of Devon with remainder to the heirs of his body. He died suddenly of pleurisy a month later on 11 June 1511, leaving his only surviving son, Henry Courtenay (d.1539), to inherit the earldom.[32]

In December 1512 Henry Courtenay (d.1539) obtained by Act of Parliament the reversal of the 1504 attainder of his father, William Courtenay. In 1512 he thus inherited the earldom of Devon as held by his grandfather, having at his father's death the previous year already inherited the earldom conferred by patent on his father in 1511.[33] In 1525 he was created Marquess of Exeter by Henry VIII. However, in 1538 he was tried, convicted, attainted and beheaded by the same king for conspiring with the Poles and Nevilles against the government of Thomas Cromwell in the aftermath of the Pilgrimage of Grace. All his titles were forfeited by his attainder.[34]

Fifth creation, 1553

[edit]Edward Courtenay (d.1556), Henry Courtenay's second but only surviving son, was a prisoner in the Tower of London for fifteen years, from the time of his father's arrest to the beginning of the reign of Queen Mary (1553–1558), when he was released and created by her Earl of Devon. The patent differed from earlier patents in that it granted the earldom to his heirs male forever, rather than to the heirs male of his body. (This meant, as was decided in 1831, that the earldom could pass to his cousins, the Courtenays of Powderham, more specifically to William IV Courtenay (1527–1557), known retrospectively as the de jure 2nd Earl, which family had existed since the 14th century at that seat as prominent country gentry.) He was proposed as a prospective husband for his cousin Queen Mary, herself keen on the match, but is said to have refused her advances, after which Queen Mary married Philip II of Spain.[35] He was considered as a possible husband for her sister, the future Queen Elizabeth I. This made him a threat to Mary's reign. Moreover, he was implicated in Wyatt's rebellion, and was again locked up in the Tower. In 1555 he was permitted to travel to Italy, where he died at Padua in 1556, possibly due to poisoning. With his death, his male line was extinguished, and the earldom with it, or so it was considered until 1831.

Interregnum

[edit]Since there was no Earl of Devon, James I granted the title in 1603 to Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy, whose aunt had been the last Earl's mother. He died without legitimate children three years later, and the King gave (or rather sold) the Earldom to William Cavendish, 1st Baron Cavendish.

Meanwhile, the descendants of Sir Philip Courtenay (1340–1406), of Powderham, a younger son of the 2nd/10th Earl, having fought against the Courtenay Earls during the Wars of the Roses, lived under the Tudors as prominent country gentlemen.[36] The baronetcy was created in the Baronetage of England during the English Civil War in February 1644 for William VI Courtenay (1628–1702) de jure 5th Earl of Devon, of Powderham, Devon.[37] The third baronet gained the title Viscount Courtenay of Powderham in 1762.

In 1831, the senior living Courtenay of this line was William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay (died 1835), an aged rake and bachelor, then living in exile in Paris, having fled a bill of indictment. Were he to die unmarried, the viscountcy would become extinct, while the baronetcy would be inherited by his third cousin, another William Courtenay (1777–1859), who was Clerk Assistant to Parliament and High Steward of Oxford University. William Courtenay (d.1859) persuaded the House of Lords that "heir male" in the last 1553 creation of the title had meant "heir male collateral", and that his cousin the 3rd Viscount was therefore also 9th Earl of Devon, and his ancestors the Courtenays of Powderham had been de jure Earls of Devon from 1556. William Courtenay (died 1859) duly succeeded his cousin as 10th Earl in 1835, and from him, the present Earls are descended. (A madman, John Nichols Thom, claimed to be "Sir William Courtenay" in 1832, and stood for Parliament twice, as representative of the extreme Philosophical Radicals, and proclaimed his right to the Earldom. He organized an agricultural rising outside Canterbury in 1838, and was shot dead in the Battle of Bossenden Wood during its suppression.)

The inconvenience, since 1831, of having two Earls for the same county has been dealt with thus: The Cavendish Earls, who were elevated to a Dukedom in 1694, had been spelling their title Duke of Devonshire; the ancient Earls had usually been Earls of Devon. This is due in part to the differences between English and "law Latin", the language in which royal decrees were traditionally written. This has now become the difference between the two peerages, and it is convenient to call the Blount Earl (1603–06) Earl of Devonshire also.

Residences

[edit]The principal seat of the Earls of Devon until the expiry of the senior line in 1556 was Tiverton Castle in Devon, and as a subsidiary seat Colcombe Castle, Devon, both of which are now largely demolished. The Earls of Devon created after 1556, or in existence de jure, had occupied the manor of Powderham in Devon since the late 14th century, and Powderham Castle continues to be the principal seat of the present Earl of Devon.

Earls of Devon, First Creation (1141)

[edit]

- Baldwin de Redvers, 1st Earl of Devon (c. 1095–1155)

- Richard de Redvers, 2nd Earl of Devon (died 1162) son

- Baldwin de Redvers, 3rd Earl of Devon (died 1188) son

- Richard de Redvers, 4th Earl of Devon (died c. 1193), brother

- William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon (died 1217), uncle

- Baldwin de Redvers (died 1216)

- Baldwin de Redvers, 6th Earl of Devon (1217–1245), grandson of the 5th Earl

- Baldwin de Redvers, 7th Earl of Devon (1236–1262) son

- Isabel de Redvers, 8th Countess of Devon (1237–1293), sister

Earls of Devon of the early Courtenay line

[edit]

The ordinal number given to the early Courtenay Earls of Devon depends on whether the earldom is deemed a new creation by the letters patent granted 22 February 1334/5 or whether it is deemed a restitution of the old dignity of the de Redvers family. Authorities differ in their opinions, and thus alternative ordinal numbers exist, given here.[38]

- Hugh de Courtenay, 1st/9th Earl of Devon (1276–1340) (cousin; declared Earl 1335)

- Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd/10th Earl of Devon (1303–1377) (son)

- Edward de Courtenay (died bef. 1272)

- Edward de Courtenay, 3rd/11th Earl of Devon (1357–1419), "The Blind", (grandson of the 2nd/10th Earl)

- Hugh de Courtenay, 4th/12th Earl of Devon (1389–1422) (son)

- Thomas de Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (1414–1458) (son)

- Thomas Courtenay, 6th/14th Earl of Devon (1432–1461) (son) (attainted 1461)

- John Courtenay, 7th/15th Earl of Devon (1435–1471) (brother) (restored 1469; in abeyance from 4 May 1471 to 14 October 1485, subject to revival of earlier attainder of 1461)

Earl of Devon, Second Creation (1469)

[edit]- Humphrey Stafford, 1st Earl of Devon (1439–1469) (granted May 1469; forfeited August 1469)

Earl of Devon, Third Creation (1485)

[edit]

- Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (died 1509), KG, (forfeited at his death by son's attainder; restored 1512 to his grandson)

- Heir male to John Courtenay above; attainted 1484; restored to lands and honours then lost in 1485; if this was intended to restore the first Earldom, it was also forfeit 1538/9.

Earls of Devon, Fourth Creation (1511)

[edit]

- William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475–1511) (attainted 1504; restored to the rights of a subject 1511; new creation two days later; died the next month without investiture, but buried as an Earl) son of Edward above.

- Henry Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (1498–1539) KG; (heir to both 3rd and 4th creations after 1512); son of William above. (created Marquess of Exeter in 1525).

Marquess of Exeter, First Creation (1525)

[edit]- Henry Courtenay, 1st Marquess of Exeter (1498-1539); attainted 1538/9, executed and all titles and honours forfeit.

Earls of Devon, Fifth Creation (1553)

[edit]

- Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1527–1556) (also restored in blood, but not honours, 1553; fifth creation dormant 1556†) son of Henry above. Died unmarried and without children.

Earls de jure, of Powderham

[edit]- William Courtenay, de jure 2nd Earl of Devon (1529–1557), of Powderham, sixth cousin once removed of Edward above,

- William Courtenay, de jure 3rd Earl of Devon (1553–1630)

- William Courtenay (died 1605), his eldest son, died before his father

- Francis Courtenay, de jure 4th Earl of Devon (1576–1638), his brother

- William Courtenay, de jure 5th Earl of Devon, 1st Baronet (1628–1702) (created 1644)

- Francis Courtenay (died 1699), his eldest son, died before his father

- William Courtenay, de jure 6th Earl of Devon, 2nd Baronet (1675–1735), son of Francis

- William Courtenay, de jure 7th Earl of Devon, 1st Viscount Courtenay (11 February 1709/1710 – 16 May 1762) (created Viscount Courtenay 1762)

- William Courtenay, de jure 8th Earl of Devon, 2nd Viscount Courtenay (30 October 1742 – 14 October 1788)

- William Courtenay, de jure 9th Earl of Devon (1788–1835), de facto 9th Earl of Devon (1831–1835), 3rd Viscount Courtenay (1768–1835; earldom retrospectively revived 1831†)

Revived (1831)

[edit]

- William Courtenay, 9th Earl of Devon (1768–1835), died unmarried

- William Courtenay, 10th Earl of Devon (1777–1859), his second cousin: elder son of Rt. Rev. Henry Reginald Courtenay, Bishop of Exeter, who was the second son of Henry Reginald Courtenay, MP, who was the second son of Sir William Courtenay, 2nd Baronet

- William Reginald Courtenay, 11th Earl of Devon (1807–1888), his eldest son

- William Reginald Courtenay (1832–1853), his eldest son, died — unmarried — before his grandfather

- Edward Baldwin Courtenay, 12th Earl of Devon (1836–1891), his brother, died unmarried

- Henry Hugh Courtenay, 13th Earl of Devon (1811–1904), a priest; his uncle, second son of the 10th Earl

- Henry Reginald Courtenay, Lord Courtenay (1836–1898), his eldest son, died before his father

- Charles Pepys Courtenay, 14th Earl of Devon (1870–1927), his eldest son

- Henry Hugh Courtenay, 15th Earl of Devon (1872–1935), a priest; his brother

- Frederick Leslie Courtenay, 16th Earl of Devon (1875–1935), a priest; his brother

- Henry John Baldwin Courtenay, Lord Courtenay (b. and d. 1915), his elder son, died before his father

- Charles Christopher Courtenay, 17th Earl of Devon (1916–1998), Frederick's younger son

- Hugh Rupert Courtenay, 18th Earl of Devon (1942–2015), his only son

- Charles Peregrine Courtenay, 19th Earl of Devon (born 1975), his only son

The heir apparent is the present holder's only son Jack Haydon Langer Courtenay, Lord Courtenay (born 2009)

†: 1553 creation was with remainder to his heirs male whatsoever, so theoretically succeeded by his sixth cousin once removed; thus the 1831 revival was to the ninth member of the family with respect to said creation.

Family tree

[edit]| de Redvers & Courtenay Family Tree, including: Earls of Devon (Creations of 1141, 1485, 1511 & 1553); Courtenay Barons (1299); Marquess of Exeter (1525); Viscount Courtenay (1762); Courtenay Baronets of Powderham Castle (1644) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

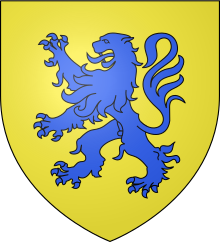

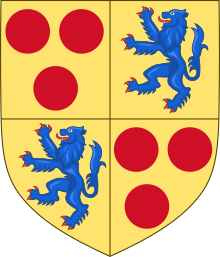

Arms

[edit]

|

|

Earls of Devonshire

[edit]While the title was supposed extinct, there were two recreations, to the families of Blount and Cavendish, of a Devon Earldom; for which see:

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Comes", Latin "companion"; the original Norman earl was different from an Anglo-Saxon ealdorman or Norse jarl, being a companion of the Duke of Normandy who was the war leader or dux and in 1066 led his army across the Channel.

- ^ Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, part 2 (notes), chapter 5. Thorn refers to Ordgar, Ealdorman of Devon as "Earl of Devon"

- ^ Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, part 2 (notes), chapter 5. Thorn refers to Ordgar, Ealdorman of Devon as "Earl of Devon"

- ^ Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, part 2 (notes), chapter 5. Thorn refers to Ordgar, Ealdorman of Devon as "Earl of Devon"

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 311–12.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 309–11.

- ^ Sanders, I.J., English Baronies, Oxford, 1960, p.137, Plympton

- ^ For details see Richard de Redvers – Was Richard the first Earl of Devon?

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 312–13.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 313–14.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 315.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 315–16.

- ^ Sanders, I.J., English Baronies, Oxford, 1960, p.70, Okehampton

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 318–19.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 319–22.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 322–3.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 323–4

- ^ Hugo nominative Latin form, Hugoni dative, i.e. writ to Hugoni...

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 323; Richardson I 2011, p. 539.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 323.

- ^ Richardson I 2011, p. 539.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 324.

- ^ Cokayne 1912, pp. 324–5; Richardson I 2011, p. 542.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 325–6; Richardson I 2011, pp. 546–7.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 326; Richardson I 2011, p. 546.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 326.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 326–7; Richardson I 2011, pp. 546–7.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 327–8.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 328.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, p. 328.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 328–9.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 328–30.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 328–30.

- ^ Cokayne 1916, pp. 328–30.

- ^ Prince, Worthies of Devon

- ^ See Battle of Clyst Heath

- ^ Cokayne, George Edward, ed. (1902), Complete Baronetage volume 2 (1625-1649), vol. 2, Exeter: William Pollard and Co, retrieved 9 October 2018

- ^ Watson, in Cokayne, The Complete Peerage, new edition, IV, p.324 & footnote (c): "This would appear more like a restitution of the old dignity than the creation of a new earldom"; Debrett's Peerage, however, gives the ordinal numbers as if a new earldom had been created. (Montague-Smith, P.W. (ed.), Debrett's Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, Kelly's Directories Ltd, Kingston-upon-Thames, 1968, p.353)

- ^ Debrett's peerage and baronetage 2003. Debrett's Peerage Ltd. 2002. p. 457.

References

[edit]- Hesilrige, Arthur G. M. (1921). Debrett's Peerage and Titles of courtesy. London: Dean & Son. p. 291.

- Burke, Sir Bernard, The English Peerage (London, 1865)[page needed]

- Burke, J.T., The Dormant, Extinct and Abeyant peerages (1971)[page needed]

- 107th edition of Burke's Peerage, Baronetage, and Knightage of Great Britain and Ireland, 3 vols., (London: 2005)[page needed]

- Watson, G.W., Earl of Devon, published in The Complete Peerage by Cokayne, George Edward, Volume IV, H.A. Doubleday (ed.), St. Catherine Press, London, 1916, pp. 308–338

- Cokayne, G. E. (1912). Gibbs, Vicary (ed.). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, extant, extinct or dormant (Bass to Canning). Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). London: The St Catherine Press.[page needed]

- Cokayne, G. E. (1916). Gibbs, Vicary & Doubleday, H. Arthur (eds.). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, extant, extinct or dormant (Dacre to Dysart). Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). London: The St Catherine Press.[page needed] – note: very useful appendices on Law of Primogeniture and blood lines, including cases in the High Court in parliament; as is the extensively researched footnotes.

- Debrett's Peerage [page needed]

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, ed. Kimball G. Everingham. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[page needed]

- Earls of Devon

- Earldoms in the Peerage of England

- Extinct earldoms in the Peerage of England

- 1st house of Courtenay

- History of Devon

- Forfeited earldoms in the Peerage of England

- Noble titles created in 1141

- Noble titles created in 1469

- Noble titles created in 1485

- Noble titles created in 1511

- Noble titles created in 1553