Pedro Castillo

Pedro Castillo | |

|---|---|

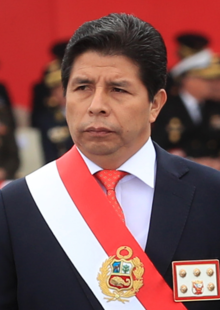

Castillo in 2022 | |

| 63rd President of Peru | |

| In office 28 July 2021 – 7 December 2022 | |

| Prime Minister | Guido Bellido Mirtha Vásquez Héctor Valer Aníbal Torres Betssy Chávez |

| Vice President | First Vice President Dina Boluarte Second Vice President Vacant |

| Preceded by | Francisco Sagasti |

| Succeeded by | Dina Boluarte |

| Personal details | |

| Born | José Pedro Castillo Terrones 19 October 1969 Puña, Peru |

| Political party | All for the People (since 2024) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | César Vallejo University (BA, MA) |

| Signature |  |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Political Career 2021-2022

Government

Crisis Others Family  |

||

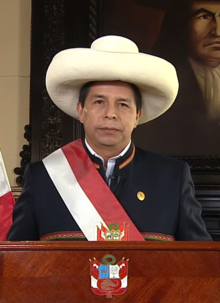

José Pedro Castillo Terrones[a] (Latin American Spanish: [xoˈse ˈpeðɾo kasˈtiʝo teˈrones] ⓘ; born 19 October 1969) is a Peruvian politician, former elementary school teacher, and union leader who served as the President of Peru from 28 July 2021 to 7 December 2022.[1][2] Facing imminent impeachment proceedings, on 7 December 2022, Castillo attempted to illegally dissolve Congress and rule by decree. In response, the Congress of the Republic of Peru (including his own political party) impeached him, resulting in his removal from office.[3][4][5][6]

Born to a peasant family in Puña, Cajamarca, Castillo began working in Peru's informal economy as a teenager to earn funds for his studies in education and later returned to his hometown to become a primary school teacher. He attained political prominence as a leading figure in a school teachers' strike in 2017 and ran in the 2021 presidential election as the candidate of the Free Peru party. Castillo announced his presidential candidacy after seeing his students undergo hardships from the lack of resources in rural Peru, with the election occurring amidst the country's COVID-19 pandemic and a period of democratic deterioration in the nation. With the support of individuals living in rural and outlying provinces, he placed first in the initial round of the presidential vote and advanced to the second round where he won against his opponent Keiko Fujimori.[7][8] Castillo's victory in the presidential race was confirmed on 19 July 2021 and he was inaugurated on 28 July.[9][10]

After taking office, Castillo named far-left and left-wing cabinets, due to the influence of Free Peru leader Vladimir Cerrón and other more left-wing politicians.[11][12][13] A social conservative, Castillo ultimately began to align his policies with Congress and Evangelical groups on social issues, including his opposition to same-sex marriage, gender studies and sex education.[14][15][16][17] He would leave the Free Peru party in June 2022 to govern as an independent.[18] In attempts to appease the right-wing Congress, he later appointed members of center and center-right political parties as ministers of state.[19][20] Castillo was noted for appointing four different governments in six months, a Peruvian record.[21]

Castillo's presidency had a minority in congress, and faced opposition which led to three impeachment proceedings, although the first two failed to reach the necessary votes to remove him from office.[19][22][23] Following the second failed impeachment vote in March 2022, protests took place across the country against high fuel and fertilizer prices caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and sanctions against Russia. Mining protests also intensified as the country's economy plummeted.[24][25] On 1 December 2022, Peru's Congress approved a motion initiated by opposition lawmakers to start the third formal attempt to impeach him since he took office.[26]

On 7 December 2022, Castillo, citing obstruction by Congress, attempted a self-coup, attempting to form a provisional government, institute a national curfew, and call for the formation of an assembly to draft a new constitution. Castillo was impeached by Congress within the day and was detained for sedition and high treason.[27][28] He was succeeded by First Vice President Dina Boluarte. After his removal, pro-Castillo protests broke out calling for new elections and the release of Castillo from detention, to which the new government of President Boluarte, who swiftly allied with the opposition to Castillo, responded with violence, resulting in the Ayacucho massacre and Juliaca massacre.[29][30]

Early life and education

[edit]Castillo was born to an impoverished and illiterate peasant family in Puña, Tacabamba, Chota Province, Department of Cajamarca.[31][32][33] Despite being the location of South America's largest gold mine, Cajamarca has remained one of the poorest regions in Peru.[32][33] He is the third of nine children.[32]

His father, Ireño Castillo, was born on the hacienda of a landowning family where he performed labor-intensive work.[31][34] His family rented land from the landowners until General Juan Velasco Alvarado took power and redistributed property from landowners to peasants, with Ireño receiving a plot of land he had been working on.[31][34] As a child, Castillo balanced his schooling with farm work at home, completing his elementary and high school education at the Octavio Matta Contreras de Cutervo Higher Pedagogical Institute.[34][35] Castillo's daily trek to and from school involved walking along steep cliffside paths for two hours.[34][36]

"It was a great accomplishment for me to finish high school, which I did thanks to the help of my parents and my brothers and sisters. I continued my education, doing what I could to earn a living. I worked in the coffee fields. I came to Lima to sell newspapers. I sold ice cream. I cleaned toilets in hotels. I saw the harsh reality for workers in the countryside and the city."

As a teenager and young adult, Castillo traveled throughout Peru to earn funds for his studies.[34][38] Beginning at the age of twelve, each year he and his father walked 140 kilometres (87 mi) for seasonal work in the coffee plantations of the Peruvian Amazonia.[31][36] Castillo also sold ice cream, newspapers, and cleaned hotels in Lima.[37][better source needed] He studied Primary Education at the Octavio Carrera Education Institute of Superior Studies and gained a master's degree in Educational Psychology from the César Vallejo University.[35]

During the internal conflict in Peru that began in the 1980s, Castillo worked in his youth as a patrolman of Rondas campesinas to defend against the Shining Path.[39][40][41]

From 1995, Castillo worked as a primary school teacher and principal at School 10465 in the town of Puña, Chota.[33][35] In addition to teaching, he was responsible for cooking for his students and cleaning their classroom.[32] According to Castillo, the community constructed the school after receiving no government assistance.[37][better source needed] Rural teaching in Peru is poorly paid but highly respected and influential within local communities, which led Castillo to become involved with teachers' unions.[36][42] With his working background as a patrolman for Rondas campesinas and being a schoolteacher, two of the most respected jobs in Peruvian society, Castillo was able to establish a high level of political support.[42]

Early political career

[edit]In 2002, Castillo unsuccessfully ran for the mayorship of Anguía as the representative of Alejandro Toledo's centre-left party Possible Peru.[34][43] He served as a leading member of the party in Cajamarca from 2005 until the party's dissolution in 2017 following its poor results in the 2016 Peruvian general election.[34][44] Following his leadership during the teachers' strike, numerous political parties in Peru approached Castillo to promote him as a congressional candidate, though he refused and instead decided to run for the presidency after encouragement from unions.[31]

2017 teachers' strike

[edit]In an interview with the Associated Press, Castillo said that his motivation for entering politics was seeing his students arrive to school hungry without any benefits while, at the same time, Peru experienced economic growth from mineral wealth.[31] Castillo became a teachers' union leader during the 2017 Peru teachers' strike, which sought to increase salaries, pay off local government debt, repeal the Law of the Public Teacher Career and increase the education budget.[45] At the time, the Peruvian government sought to replace a system of career teachers with temporary unskilled educators.[10] The strikes spread through southern Peru; due to their longevity, Minister of Education Marilú Martens, Prime Minister Fernando Zavala, and other government officials jointly announced a package of salary increases and debt relief, though the teachers remained on strike.[46][47]

President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski offered to mediate, inviting the teachers' delegates to meet at the Government Palace to reach a solution; only the leaders of the union's executive committee and its Cuzco leaders were received while representatives of the regions led by Castillo were excluded.[48][49] The strike consequently worsened as teachers from across Peru travelled to Lima to hold marches and rallies in the capital.[50] Keiko Fujimori and her Fujimorist supporters, who were opponents of the Kuczynski administration, assisted Castillo with the strike in an effort to destabilize the president's government.[36]

On 24 August 2017, the government issued a supreme decree making official the benefits agreed in negotiations,[51] issuing a warning that if teachers did not return to their classrooms by 28 August, they would be fired and replaced.[52] On 2 September 2017, Castillo announced a suspension of the strike; he said it was only a temporary suspension.[53][54]

2021 presidential election

[edit]The 2021 presidential elections occurred amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru and a political crisis in the nation that continued during the election.[55] These crises created multiple political currents that eventually consolidated into a growing political polarization among Peruvians.[55]

First round

[edit]Initial discussions between former Governor of Junín, Vladimir Cerrón of Free Peru, and Verónika Mendoza of Together for Peru, recommended a leftist coalition to support a single presidential candidate in the 2021 general election. Mendoza's advisors argued that Cerrón's beliefs were too radical and of an antiquated left wing ideology.[56] Mendoza's camp also raised concerns about Cerrón's alleged homophobic and xenophobic rhetoric.[56] In October 2020, Castillo announced his presidential bid, running as the candidate of Free Peru, and formally attained the nomination on 6 December 2020. His ticket included attorney Dina Boluarte and Vladimir Cerrón; Cerrón was later disqualified by the National Jury of Elections due to a corruption conviction.[39]

Pedro Castillo was chosen by a national assembly of teachers' representatives to be their candidate for the presidential election of 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of financial resources led them to give up building a political party. Approached by several small parties, he chose Free Peru (Perú Libre, PL), of which he was not a member at the time.[57]

During the first part of the campaign, unknown to most Peruvians, Pedro Castillo was very low in the polls and received very little media coverage. His campaign accelerated from March, when he crossed the threshold of 5% of voting intentions.[57]

Castillo cited the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on his students as a motivation for his presidential run.[32] In response to the pandemic, President Martín Vizcarra initiated COVID-19 lockdowns in Peru, inhibiting trade and travel to rural Peru.[42] As a result of the lockdowns, individuals in rural regions felt an increased sense of abandonment from the national government, with political groups in these regions beginning to act in autonomous manners and experiencing growth in their legitimacy.[42] Castillo told the Associated Press that he had attempted to continue teaching his students through the lockdowns, but the impoverished local community did not have the resources required for remote learning; almost none of his students had access to a cell phone, and educational tablets promised by the government never arrived.[32] Using this experience of abandonment and distrust of the national government established in urban Lima, Castillo had a genuine ability to relate to rural voters and used his knowledge of their issues to establish support.[42]

He campaigns for a constitutional reform (he believes that the current Constitution of Peru, promulgated in 1993 under President Alberto Fujimori, is responsible for the economic inequalities of the country because it consecrates a free market model), a restructuring of the pension system and the nationalization of the gas industry. His program is based on three main themes: health, education and agriculture, which he intends to strengthen to stimulate the country's development. He enjoys a certain image of probity, as he is one of eight candidates (out of 18) who have not been cited in any case in a country where political corruption is high. Castillo said he would pardon Antauro Humala, a member of the Ethnocacerist movement and brother of former President Ollanta Humala who was sentenced to nineteen years in prison after leading the capture of a police station in Andahuaylas that had resulted in the deaths of four policemen and one gunman.[58][59] At the conclusion of his initial campaign ahead of the first round of voting, Castillo held a rally in the Historic Centre of Lima, beginning at the Plaza San Martín before leading a march on horseback to the Plaza Dos de Mayo, where hundreds of supporters gathered.[40] At the event, he told attendees that if elected, the citizens would supervise his policies, he would only receive the salary of a teacher, and sought to reduce the pay of congress and ministers by half.[40]

Trailing throughout the entire campaign, his polling surged during the last weeks of the campaign and on election day, Castillo secured 18% of the vote in the first round, putting him in first place among eighteen candidates. His success was attributed to his focus on the large difference of living standards between Lima and rural Peru, leading to strong support in countryside provinces.[60] He faced the second-placed candidate, Keiko Fujimori, who had also finished second place in the 2011 and 2016 general elections, in the second round of voting.[61]

After his victory in the first round, Castillo called for Peruvian political forces, including trade unions and Ronda Campesinas, to establish a political agreement, though he declined to make a roadmap similar that of Ollanta Humala during the 2016 general election.[62][63] He established a political alliance with the left-wing former presidential candidate Verónika Mendoza in May 2021, earning her support for his campaign.[64][65]

Second round

[edit]

Approaching the second round of presidential elections, it became apparent that Castillo's policy proposals would be unlikely to be enacted as president and that he would be vulnerable to Congress; the newly elected Congress of Peru was made of opposing parties, with his party having only over 37 of the 130 seats in congress.[32][66]

While campaigning, Castillo was insulted on multiple occasions by individuals likening him to Nicolás Maduro, president of Venezuela,[67][68][69] while Free Peru reported that he also received anonymous death threats.[70] Third-place candidate Rafael López Aliaga issued death threats during a demonstration against Castillo, shouting: "Death to communism! Death to Cerrón! Death to Castillo!"[71] Castillo was also criticized for his debate performance with critics raising questions on whether he understood governmental functions.[72]

Castillo ultimately won the election, handing Fujimori her third consecutive defeat in a presidential election.[9][73]

Reactions

[edit]Many observers described the second round of the presidential election as being a choice between the lesser of two evils.[74] The transfer of the presidency to Castillo was described by the Institute of Peruvian Studies as "strengthening the current Peruvian democratic regime", as the process was peaceful and contributed to a "more prolonged democratic stability" in Peru in the early 21st century.[75] The New York Times reported his victory as the "clearest repudiation of the country's establishment",[76] and the Financial Times described him as "a hope for the poor", amid concerns among the establishment and the elite, which resulted in a capital flight, in a country that was hit the most by the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to excess mortality, with an economy in recession, a collapsed healthcare, a series of corruption scandals, and one third of Peruvians living in poverty.[74]

Following Castillo's surprising success in the first round of elections, the S&P/BVL Peru General Index fell by 3.2% and the Peruvian sol saw its value drop 1.7%, its biggest loss since December 2017 during the first impeachment process against Pedro Pablo Kuczynski;[77][78] in the week before the run-off vote, the sol continued to post historical lows against the U.S. dollar.[74] An economist told the Financial Times that they have not seen such a serious capital flight in two decades.[74] Optimistic observers felt that Castillo would moderate his views, citing former president Ollanta Humala as an example. Pedro Francke, a university professor of economics, rejected comparisons of his style of leadership to those seen in Cuba or Venezuela, and instead suggested that his governing style would be more similar to that of leftist leaders like Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Evo Morales,[74] and José Mujica. Daniel Rico of RBC Capital Markets credited Francke with calming markets fears of Castillo, who was characterized by opponents as a far-left politician.[79]

Most regional leaders and some in Europe, such as Pedro Sánchez of Spain, extended congratulations and wished Castillo the best on being the president of the bicentennial of Peru.[80] Lula da Silva, leftist former president of Brazil, congratulated him and said that Castillo had struck a blow to conservatism in the region, saying that "the result of the Peruvian polls is symbolic and represents another advance in the popular struggle in our dear Latin America".[81] Like Lula, Morales, the former president of Bolivia, congratulated Castillo, stating that Castillo "won with our proposal" and that he had spoken to him on the phone previously.[82] Mujica, the former Uruguayan president, also shared approval of Castillo's success in the first round of elections, warning Castillo to "not fall into authoritarianism", while participating in a Facebook live video call with him.[83][84] Colombian president Iván Duque and Ecuadorian president Guillermo Lasso congratulated Castillo on his victory.[85]

Presidency (2021–2022)

[edit]Castillo was officially designated as president-elect of Peru on 19 July 2021, only a week before he was to be inaugurated.[76] Days before his designation, Castillo and his economic advisor Pedro Francke met with Ambassador Liang Yu at the Chinese embassy in Peru to discuss a more rapid introduction of Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccines in Peru.[86] The majority of ministers chosen by Castillo were from interior regions in contrast to previous governments where most ministers originated from Lima.[87][better source needed] Ministers were mainly from allied leftist and independent organizations, while three ministers were from Free Peru and another three were previous teachers close to Castillo.[87][better source needed]

Castillo and his government's political experience and direction had been described as being unclear by observers,[88][89] as he lacked notable political experience prior to his election.[90][91] In a little more than his government's first six months, four different cabinets were selected after being dissolved following numerous corruption controversies affecting Castillo and his close advisors.[21][89] According to political analyst Gianfranco Vigo, the Castillo administration "is governed not so much by knowledge but rather by closeness".[21] Castillo responded to criticism of his experience in an interview with CNN, saying that governing was "a learning process" and he was not "trained to be president", explaining that he did not study abroad by choosing to stay "for the country, for the people".[92] He also stated during the interview that Free Peru leader Vladimir Cerrón had "no influence on cabinet appointments".[92] About Castillo's government, political scientist Paula Távara of the National University of San Marcos said it has not shown "any clear direction" and "has not yet tackled any of the promised political projects. ... Instead it is sinking into chaos, with new ministers constantly being appointed with no qualifications other than their party membership. Posts are distributed on a whim to forge political alliances."[93]

In April 2022, Free Peru drafted a bill calling for general elections in 2023 to elect a new president and congress.[94] By late 2022, Castillo aligned with right-wing groups in Congress, meeting with the conservative group Con mis hijos no te metas and various evangelical groups to push for laws preventing the teaching of gender studies and detailed sexual education in schools.[15]

Domestic policy

[edit]

According to Farid Kahhat of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, Castillo's economic policy was created in collaboration with Verónika Mendoza, utilizing New Peru economists who have an established history of holding public office.[65] His first Minister of Economy and Finance was Pedro Francke, a former World Bank and Central Reserve Bank of Peru economist who assisted Castillo with moderating his policies.[95][96] Kahhat explained that Castillo proposed taxing windfall profits, describing these profits as "the product of good international prices and not the merit of the company itself".[65] Upon taking office, Castillo also appointed feminist and pro-LGBT activist Anahí Durand as head of the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations, with Prime Minister Guido Bellido releasing a statement promising to "beat racism, classism, machismo, and homophobia".[97]

In September 2021, Castillo announced funding of 99 million soles (US$24 million) to provide food for impoverished families, stating: "We cannot understand that, despite having so much wealth in the country, it is not balanced with development."[98] As announced during his campaign, he launched an agrarian reform in October 2021, which he promises will not involve expropriations.[99] It includes an industrialization plan for peasants to promote the development of agriculture, and intends to offer poor peasants fairer access to markets.[99] Following the death of Abimael Guzmán, the founder of Shining Path, Castillo said his government's "condemnation of terrorism is firm" and he condemned Guzmán, saying he was "responsible for the loss of innumerable lives of our compatriots".[100]

In November 2021, Castillo announced an increase in the minimum wage from 930 to 1,000 sols ($223 to $250), the sale of the presidential jet acquired in 1995, and a ban on first-class travel for all civil servants.[101] That month, the Central Reserve Bank of Peru reported that from July through September 2021 Peru's GDP grew by 11.4% and beat previous expectations, with Bloomberg News saying Peru experienced the fastest growing economy among Latin American nations at the time.[102] The International Monetary Fund supported tax increases on the mining sector, reporting in December 2021 that Peru could safely increase taxes since the country had "a tax burden that is lower or similar to other resource-rich countries".[103]

After Castillo's acquittal of the second impeachment attempt against him in February 2022, global economic reverberations resulted from international sanctions during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine,[104][105] inflation in Peru rose sharply,[106] prompting protests.[107][108] By April 2022, the inflation rate in Peru rose to its highest level in 26 years, creating greater difficulties for the recently impoverished population.[106] Inflation of basic goods, alongside increasing fertilizer and fuel prices as a result of the war, angered rural Peruvians, and shifted them from their position of supporting Castillo to protesting his government.[108][104] According to Convoca, UGTRANM leader Diez Villegas, the same individual who attempted to organize strikes in October 2021, called for a general strike of transportation workers for 4 April 2022.[109] These strikes later expanded, culminating with the 2022 Peruvian protests.[109]

Foreign policy

[edit]Héctor Béjar, the newly appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs, said that Peru would no longer support international sanctions during the Venezuelan crisis and did not clarify his position on recognizing Juan Guaidó as part of the Venezuelan presidential crisis.[110] Béjar resigned on 17 August 2021, amid criticism from the opposition and some media over his statement that Peru's navy had been responsible for terrorist acts and that the CIA had created the Shining Path.[111] During his first Foreign Relations Commission with Congress, Castillo's second foreign minister Óscar Maúrtua said that Peru would remain a member of the Andean Community, the Pacific Alliance, and PROSUR, saying that Castillo's government held the "objective of achieving South American integration, for the benefit of our peoples", while also offering refuge to Afghan refugees following the Fall of Kabul.[112]

For his first international trips, Castillo traveled to Mexico on 17 September 2021 and later to the United States on 19 September.[113] During his tour in the United States, Castillo and economic minister Pedro Francke met with foreign investors, along with representatives from the United States Chamber of Commerce, Pfizer, and Microsoft.[114][115] Some of Peru's largest investors, such as Freeport-McMoRan and BHP, shared positive reactions of the Castillo government following their meetings.[114] Castillo later spoke at the 76th session of the United Nations General Assembly on 21 September, proposing the creation of an international treaty signed by world leaders and pharmaceutical companies to guarantee universal vaccine access internationally, stating: "On behalf of Peru, I want to propose the signing of a global agreement between Heads of State and patent owners to guarantee universal access to vaccines for all inhabitants, without discrimination or privileges, which would be a sign of our commitment to the health and lives of all peoples."[116][117] Castillo argued: "The battle against the pandemic has shown us the failure of the international community to cooperate under the principle of solidarity."[116]

During a January 2022 interview with CNN en Español, Castillo said that he would consult for a plebiscite in order to grant Bolivia access to the sea. Castillo's remarks received both positive and negative reactions in Peru.[118] In June 2022, Castillo convened the leaders of different South American nations to treat the Venezuelan migrant crisis, with Peru being home to 1.3 million Venezuelans that fled following the crisis in Venezuela.[119]

According to Peruvian law, the president must have the authorization of Congress every time he wants to travel abroad, with the legislative body banning Castillo from participating in foreign affairs on multiple occasions. Congress banned Castillo from traveling to Colombia for the inauguration of the new president, Gustavo Petro, denied permission to travel to the Vatican to meet with the Pope, to Thailand for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit and to Mexico for a meeting of the Pacific Alliance in November 2022; the latter was cancelled and rescheduled for 14 December 2022 in Lima, though never occurred.[120][121]

Removal attempts

[edit]In October 2021, the website El Foco released recordings revealing that leaders of the manufacturing employers' organization National Society of Industries, the leader of the Union of Multimodal Transport Guilds of Peru (UGTRANM), Geovani Rafael Diez Villegas, political leaders, and other business executives planned various actions, including funding transportation strikes in November 2021, in order to destabilize the Castillo government and prompt his removal.[122] Far-right groups of former soldiers also allied with political parties like Go on Country – Social Integration Party, Popular Force, and Popular Renewal in an effort to remove Castillo, with some veteran leaders seen directly with Rafael López Aliaga and Castillo's former presidential challenger Keiko Fujimori, who signed the Madrid Charter promoted by the Spanish far-right political party Vox.[123][124] These groups directed threats towards Castillo government officials and journalists, whilst also calling for a coup d'état and insurgency.[124] OjoPúblico compared the veteran groups, such as the far-right neofascist La Resistencia Dios, Patria y Familia militant organization that was supported by Popular Force and Popular Renewal, to the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys of the United States, noting a possible threat of an event similar to the 2021 United States Capitol attack occurring in Peru.[124][125] Hundreds of members of La Resistencia and Fujimorists had already attempted to storm the Government Palace in July 2021 in rejection of election results, though such groups were repelled by authorities.[126][127][128][129]

Tensions with Congress, dominated by conservative parties, were particularly high. The legislative body attempted to remove Castillo multiple times, accusing him of corruption, though charges only went as far as preliminary investigations.[19] Congress approved a law interpreting the constitution that restricted the executive's ability to dissolve Parliament, while Parliament retained the right to impeach the President. In December 2021, Congress passed a law that a referendum to convene a Constituent Assembly, one of Pedro Castillo's key promises during the presidential election, could not be held without a constitutional reform previously approved by Parliament. During a visit to the Spanish Parliament, the president of the Peruvian Congress, María del Carmen Alva, asked the deputies of the Popular Party to approve a declaration stating that "Peru has been captured by communism and that Pedro Castillo is a president without any legitimacy."[130]

November–December 2021 impeachment attempt

[edit]Presented in visitor documents as a lobbyist for the construction company Termirex, Karelim López met with Castillo's chief of staff Bruno Pacheco multiple times.[131] In November 2021, four months into his term, Keiko Fujimori announced that her party was pushing forward impeachment proceedings, arguing that Castillo was "morally unfit for office".[132] That day, investigators raided the Government Palace during an influence peddling investigation and found that Pacheco had US$20,000 present in his office's bathroom.[133][134] Pacheco said that the money was part of his savings and salary, though he resigned from his position in order to prevent the scandal from affecting Castillo.[133] On 25 November 28 legislators from Fujimori's party presented a signed motion of impeachment to congress, setting up a vote for opening impeachment proceedings against Castillo.[134] A short time later, controversy arose when newspapers reported that Castillo had met with individuals at his former campaign headquarters in Breña without public record, a potential violation of a recently created, complicated set of transparency regulations.[135] Lobbyist Karelim López would also become entangled with the controversy in Breña after the company Terminex, who she lobbied for, won the Tarata III Bridge Consortium contract worth 255.9 million soles.[131][136][137] Audios purportedly obtained at the residence and released by América Televisión were criticized and dismissed as a scam.[138] Castillo responded to the impeachment threat stating: "I am not worried about the political noise because the people have chosen me, not the mafias or the corrupt."[134] The impeachment proceeding did not occur, as 76 voted against proceedings, 46 were in favor, and 4 abstained, with a requirement of 52 favoring proceedings not being obtained.[139] Free Peru ultimately supported Castillo through the process and described the vote as an attempted right-wing coup.[140] Castillo responded to the vote stating: "Brothers and sisters, let's end political crises and work together to achieve a just and supportive Peru."[139]

February 2022 impeachment and acquittal

[edit]In February 2022, it was reported that Fujimorists and politicians close to Fujimori organized a meeting at the Casa Andina hotel in Lima with the assistance of the German liberal group Friedrich Naumann Foundation, with those present including Maricarmen Alva, President of the Congress of the Republic of Peru, discussing plans to remove President Castillo from office.[141] Alva had already shared her readiness to assume the presidency of Peru if Castillo were to be vacated from the position and a leaked Telegram group chat of the Board of Directors of Congress that she heads revealed plans coordinated to oust Castillo.[142][143] A second impeachment attempt related to corruption allegations did make it to proceedings in March 2022.[23] On 28 March 2022, Castillo appeared before Congress calling the allegations baseless and for legislators to "vote for democracy" and "against instability", with 55 voting for impeachment, 54 voting against, and 19 abstaining, not reaching the 87 votes necessary for impeaching Castillo.[23][144]

In July 2022, a fifth inquest was launched into Castillo's alleged involvement in corruption.[145]

Self-coup attempt and removal from office

[edit]On 7 December 2022, hours before the Congress of Peru was scheduled to vote on a third impeachment motion against him, Castillo, tried to institute an illegal self coup, citing obstruction by Congress, he declared a national curfew, the dissolution of Congress, and the installation of a "government of exceptional emergency."[28] Shortly after his announcement, a majority of Castillo's cabinet resigned, and the attempted dissolution was denounced as a coup by the Ombudsman of Peru.[146] The Constitutional Court and First Vice President Dina Boluarte also called it a coup d'état attempt,[147][27] one meant to obstruct the impeachment process.[148] Castillo was then impeached and removed from the presidency by the Congress of Peru later on 7 December, as scheduled. The impeachment passed with a majority 101 for and 6 against out of 130 votes. Boluarte, who had broken with Castillo after the announcement, ascended to the presidency.[149]

Castillo reportedly attempted to flee the country but was detained by the National Police.[150][151] He is held in preventive custody while being investigated for “rebellion and conspiracy”, and has shared the same prison as Alejandro Toledo and Alberto Fujimori (the latter was released in December 2023 and died nine months later).[152][153][154]

Recognition

[edit]

Pedro Castillo

Dina Boluarte

Recognition of Castillo's impeachment internationally was recognized,[155][156] with countries like Spain and China, and organizations like European Union recognizing Boluarte and championing a return to "constitutional order."[157][158] The American continent was more mixed. Members of the São Paulo Forum like Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil and Gabriel Boric of Chile recognized Boluarte as new president. The United States, Costa Rica and Canada recognized Boluarte as president.[159]

However, left-wing Latin American governments, including Bolivia, Colombia, Honduras, Mexico and Venezuela continued to recognize Pedro Castillo as the democratically elected President of Peru following the events in December 2022 and refused to recognize Boluarte.[160][161][162] Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela, Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico, Gustavo Petro of Colombia, Alberto Fernández of Argentina, and Luis Arce of Bolivia denounced Boluarte's government as a coup, comparing the situation as similar to ascension of Bolivia's Jeanine Áñez during the 2019 Bolivian political crisis. The latter presidents continue to support Pedro Castillo's claims he is the rightful president under a "government of exception."[163][164]

Political positions

[edit]"We have fought against terrorism and we will continue to do so. ... We are going to defend the constitutional rights of the country, there is no Chavismo, there is no communism ... ."

Castillo has been described as having far-left,[166][167] socialist,[168] populist[169] economic policies while being socially conservative.[170][14][17] He said that he is not a communist or a Chavista, although his party is.[171] Peru's attitude towards LGBT rights has generally been hostile and is heavily influenced by the Catholic Church, and Castillo is said to be more in line with his right-wing opponents on social issues, opposing abortion, LGBT rights,[172] same-sex marriage,[16] euthanasia, sex education,[33][15] and the gender-equality approach in schools;[173][174][175] this put him at odds with the progressive left that has supported him. Castillo's participation in the second round of the 2021 Peruvian presidential election placed him as one of two socially conservative candidates,[34] in a highly polarized election.[176][177][178]

The Economist wrote that Castillo "combines radical rhetoric with pragmatism", and cited his work with both left-wing and right-wing groups, including Keiko Fujimori's Popular Force, during the 2017 teachers' strike.[66] Le Monde diplomatique wrote that Castillo maintained support prior to being elected because his positions were "rather vague".[10] Castillo later distanced himself from the far-left of the Free Peru party, stating that "the one who is going to govern is me" and there will be "no communism" in Peru under his government.[41][165][179] Kahhat said Castillo limited his relationship with Free Peru and separated himself from the party's leader, adding that "it is important to remember that Castillo is a candidate but not a party member. ... [W]e might even say he is more conservative than the ideals of [Free Peru] would suggest."[65] Anthony Medina Rivas Plata, a political scientist at the Catholic University of Santa María, said that "Castillo's rise is not because he is left-wing, but because he comes from below. He has never said he is a Marxist, socialist or communist. What he is, is an evangelical."[180]

After winning the first round of presidential elections, Castillo presented his ideas in a more moderated manner, maintaining a balance between the leftist ideals of Free Peru and the conservative consensus of Peruvians.[181][182] Following his ascent to the presidency, Free Peru broke from Castillo, who distanced himself from Vladimir Cerrón,[34] believing that he moderated his positions to appease businesses and opposing politicians.[132] On 30 June 2022, Castillo resigned from Free Peru.[183]

Domestic

[edit]Economy

[edit]Castillo has expressed his interest in moving Peru more towards a mixed economy.[182] He promised foreign businesses that he would not nationalize companies in Peru, saying that those seeking the nationalization of industry within his party were part of the "leftist fringe".[179] Some of his main economic proposals were to regulate "monopolies and oligopolies" in order to establish a mixed economy and to renegotiate tax breaks with large businesses.[182] Castillo has made statements supporting increased regulation, directly criticizing Chilean companies Saga Falabella and LATAM Airlines Group.[184] Citing the fact that LATAM owes Peru nearly $1 billion, Castillo called for a state-owned national airline.[184] In an interview with CNN, he stated that if elected, he would hold discussions with businesses to ensure that "70% of profits must remain for the country" and that "they take 30%, not the other way around as it is today".[39]

Castillo proposed increasing the education and health budgets to at least ten percent of Peru's GDP.[33][174] He received criticism from EFE for not clarifying how these policies would be funded,[185] as Peru's existing government budget is already fourteen percent of the country's GDP.[174] Castillo believes that internet access should be a right for all Peruvians.[182] He proposed a science and technology ministry that would immediately be tasked with combating the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru.[182]

Regarding mining in Peru, Castillo supports the extraction of minerals throughout Peru, "where nature and the population allow it", and welcomes international investment regarding these projects.[39] For agrarian reform, Castillo proposed making Peru less reliant on importing agricultural goods and incentivizing food production for local use instead of solely for export.[64]

Governance

[edit]A main proposal of Castillo is to elect a constituent assembly to replace the constitution inherited from Alberto Fujimori's regime, with Castillo saying "it serves to defend corruption at macro scale".[33][186][187] Castillo has said that, in his efforts to rewrite the Peruvian constitution, he would respect the rule of law by utilizing existing constitutional processes and call for a constitutional referendum to determine whether a constituent assembly should be formed or not; to hold a referendum, Castillo would require a majority vote from congress, which is unlikely and limits his chances of changing the constitution.[65][182][188] All proposed reforms would also have to be approved by congress.[182]

At an event called Citizen Proclamation – Oath for Democracy, Castillo signed an agreement vowing to respect democracy, stating: "I swear with all my heart, I do swear with all my heart, that I will respect true democracy and equal rights and opportunities of the Peruvian people, without any discrimination and favoritism."[188] Castillo also promised at the event to respect the presidential term limit of a five-year tenure, saying that if elected, he would not adjust mechanisms to extend the presidential period and would leave office on 28 July 2026.[188] Other statements by Castillo included respecting the separation of powers and recognizing the autonomy of constitutional entities.[188]

Social

[edit]Proposed social policies from Castillo include creating paramilitary groups and militarizing Peruvian youth in order to promote a revolutionary experience, calling for citizens to arm themselves in order to provide justice through "socialist administration".[173] He called for Peru to leave the American Convention on Human Rights and to reinstate the death penalty in the country.[189] Castillo also called for stricter regulations on the media in Peru.[33]

According to Castillo, issues of abortion and LGBT rights "are not a priority".[32] His socialist woman proposal (La mujer socialista) was described as "a deeply patriarchal, gender-normative view of society disguised under seemingly liberating language" by Javier Puente, assistant professor of Latin American Studies at Smith College, while the rest of his program did not include any policies regarding LGBT groups, who are vulnerable populations in Peru.

Castillo announced during his inauguration that youths who do not work or study would have to serve in the military; as there is no mandatory service in Peru, it was unclear whether Castillo would introduce conscription.[190][191]

International

[edit]Latin America

[edit]

Castillo defended the government of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, describing it as "a democratic government",[175][189][192] while his Free Peru party shared praise for the policies of Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez.[77] After winning the first round of presidential elections, Castillo stated regarding Venezuela that "[t]here is no Chavismo here", saying of President Maduro, "if there is something he has to say concerning Peru, that he first fix his internal problems."[83][179] He also called on Maduro to take Venezuelan refugees back to their native country, saying that Venezuelans arrived in Peru "to commit crimes".[83] Castillo described the Venezuelan refugee crisis as an issue of "human trafficking", and said that he would give Venezuelans who commit crimes seventy-two hours to leave Peru.[83][173][189]

Venezuela's opposition leader Juan Guaidó, who was recognized as legitimate president of Venezuela by Peru in amidst the Venezuelan presidential crisis beginning in 2019, wished that Castillo would "decide for the good of freedom" after President Maduro's foreign minister Jorge Arreaza attended Castillo's inauguration.[193][194] Guaidó warned that the Lima Group could be renamed "Quito Group" if Peru recognizes Maduro.[193] Castillo called for plans to "deactivate" the group.[195][196]

In November 2021, Castillo announced the rejection of the 2021 Nicaraguan general election results, saying they were not "free, fair and transparent elections". In addition, he supported the pressure measures against the government of Daniel Ortega by the Organization of American States.[197]

At a bilateral meeting with president of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro on 3 February 2022, Castillo was seen embracing him. Bolsonaro, who wore Castillo's straw chotano hat, said Castillo was a defender of freedom and "conservative values".[13][198] Bolsonaro and Castillo also discussed a proposed highway through the Amazon rainforest, the removal of bureaucratic trade regulations, and increased drug trade monitoring.[11]

Europe

[edit]Like Mexico's Andrés Manuel López Obrador and other Latin American left-wing politicians, Castillo has been critical of the colonisation of Latin America by Spain. During his investiture, which King Felipe VI of Spain attended, he spoke strongly against Spanish colonial rule.[199]

Controversies

[edit]Terruqueo target

[edit]"When you go out to ask for rights, they say that you are a terrorist, ... I know the country and they will not be able to shut me up, ... The terrorists are hunger and misery, abandonment, inequality, injustice."

During the terrorism in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s, the government, military, and media in Peru described individuals on the left of the political spectrum as being a threat to the nation, with many students, professors, union members, and peasants being jailed or killed for their political beliefs.[200] Such sentiments continued for decades into the 2021 election, with Peru's right-wing elite and media organizations collaborating with Fujimori's campaign by appealing to fear when discussing Castillo,[41][65][200] linking him to armed communist groups through a fearmongering political attack known as a terruqueo.[201][202][203] The terreuqueo was also used beside classist and racist rhetoric against Castillo.[201]

In 2017, Castillo's participation in the teacher's strike was criticized by Minister of the Interior, Carlos Basombrío Iglesias, who said Castillo was involved with MOVADEF, a group consisting of former members of Shining Path. Castillo said he was not involved with MOVADEF or the militant teachers' union faction CONARE and that those factions should not be involved in teaching.[204][205] In June 2018, Hamer Villena Zúñiga, the leader of the United Union of Workers in Education of Peru (SUTEP), stated that Castillo's sister, María Doraliza Castillo Terrones, was a member of MOVADEF.[206] In 2018 and 2020, the newspaper Peru.21 accused Castillo of being linked to Shining Path, and published documents citing his alleged participation in virtual meetings with the organization's leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru.[207][208][209]

Claims linking Castillo to MOVADEF and Shining Path have been refuted by Castillo himself and major media outlets. With Castillo being a member of the Ronda Campesina, which often partnered with the Peruvian Armed Forces to defend rural communities against guerrilla groups, allegations by Peruvian journalists of his links to Shining Path were contradictory.[210] The Guardian described links to Shining Path as "incorrect", and the Associated Press said that allegations by Peruvian media of links to Shining Path were "unsupported".[32][211] The Economist wrote that at the same time Castillo allegedly worked with groups linked to Shining Path, he was also partnering with right-wing legislators from Popular Force, Fujimori's party, in the same capacity.[clarification needed][66]

Complaint before the Public Ministry

[edit]According to Public Records, Castillo founded a company called Consorcio Chotano de Inversionistas Emprendedores JOP S.A.C., which he did not indicate in his resume presented to the National Jury of Elections. Former congresswoman Yeni Vilcatoma of the Popular Force, a Fujimorist party, filed a complaint for the public prosecution which opened a preliminary investigation,[212] Within the context campaign of the second round, Keiko Fujimori distanced herself from Vilcatoma and denounced her saying: "I like to win political competitions on the field."[213] Castillo said that he did not list the company because he did not remember its existence since it never operated; it is indicated that he invested 18,000 soles.[214][215] This was made public after the complaint made by journalist and columnist Alfredo Vignolo,[216] who later denounced that he received death threats through social networks by supporters of Castillo.[217]

Personal life

[edit]Castillo is married to Lilia Paredes, a teacher, and they have two children together.[32][34] Castillo says he is Catholic and has participated regularly in the local festival dedicated to the Virgin of Sorrows ("Virgen de los Dolores") held in Anguía,[218] although his wife and children are evangelical.[32][219] He is a teetotaler, practicing abstinence from consuming alcohol.[220] His family lives in a nine-room home in the Chugur District tending a farm with cows, pigs, corn, and sweet potatoes.[32][34] Castillo often wears a straw hat called a chotano, a poncho, and sandals constructed from old tires.[32][221]

Electoral history

[edit]| Year | Office | Type | Party | Main opponent | Party | Votes for Castillo | Result | Swing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | P. | ±% | |||||||||||

| 2002 | Mayor of Anguía | Municipal | Possible Peru | José Alberto Yrigoin | National Unity | 104 | 8.82% | 4th | N/A | Lost | N/A[222] | |||

| 2021 | President of Peru | General | Free Peru | Keiko Fujimori | Popular Force | 2,724,752 | 18.92% | 1st | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| General (2nd round) | 8,836,380 | 50.13% | 1st | N/A | Won | Gain[223][224] | ||||||||

Awards

[edit] Bolivia

Bolivia

Grand Collar of the Order of the Condor of the Andes (2021)[225]

Grand Collar of the Order of the Condor of the Andes (2021)[225]

Peru

Peru

Grand Master of the Order of the Sun of Peru (2021)[226]

Grand Master of the Order of the Sun of Peru (2021)[226] Grand Master of the Order of Merit for Distinguished Service (2021)[226]

Grand Master of the Order of Merit for Distinguished Service (2021)[226]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Castillo and the second or maternal family name is Terrones.

References

[edit]- ^ "Peru's Castillo assumes presidency amid political storms in divided nation". Reuters. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ "Peru Libre: Ideario y Programa" (PDF). 2021. p. 8. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Peru's Overlapping Messes". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 20 January 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

Rural and indigenous peoples have been historically under-served by Lima-based national institutions. In 2021, Peruvians elected the country's first 'campesino president,' but he faced an obstructionist opposition and proved unable to make good on any of his campaign promises, producing significant disillusion.

- ^ "Peru's president dissolves Congress, but legislators vote to replace him". NPR. The Associated Press. 7 December 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ "Peru's President Pedro Castillo replaced by Dina Boluarte after impeachment". BBC News. 7 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Marina, Diego Lopez (7 December 2022). "Peru's Pedro Castillo impeached, detained by authorities after attempting to dissolve congress". Perú Reports. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

President Pedro Castillo of Peru was ousted from office and later detained by authorities after he illegally attempted to dissolve congress hours before the body was set to vote on his impeachment.

- ^ "Presentación de resultados, segunda elección presidencial 2021" (in Spanish). ONPE. 25 June 2021. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "National Office of Electoral Processes (ONPE) official second round results" (in Spanish). ONPE. 25 June 2021. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b Aquino, Marco (19 July 2021). "Peru socialist Castillo confirmed president after lengthy battle over results". Reuters. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Migus, Romain (1 September 2021). "Can Pedro Castillo unite Peru?". Le Monde diplomatique. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Brazil's Bolsonaro presses Peru's Castillo on road through rainforest to access Pacific". Reuters. 3 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Aquino, Marco; Rochabrun, Marcelo (5 November 2021). "Peru's Congress confirms new moderate left Cabinet". Reuters. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ a b Collyns, Dan (6 February 2022). "Peru's prime minister to step down after allegations of domestic violence". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ a b Jones, Sam (5 June 2021). "Peru faces poll dilemma: a leftist firebrand or the dictator's daughter?". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

Pedro Castillo, a far-left but socially conservative union leader and teacher, ... .

- ^ a b c "Las privilegiadas visitas de pastores evangélicos a congresistas y Palacio de Gobierno". Wayka (in Spanish). 12 August 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Far-left schoolteacher, rightwing populist vie for Peru presidency". France 24. 13 April 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

Both candidates are socially conservative – opposed to abortion and gay marriage.

- ^ a b Asensio et al. 2021, pp. 55–56.

- ^ "Peruvian President Pedro Castillo leaves Marxist political party that helped bring him to power". Perú Reports. 5 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Garzón, Aníbal (1 January 2023). "Peru's permanent coup". Le Monde diplomatique. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo nombra a un congresista moderado para liderar el Consejo de Ministros". France 24 (in Spanish). 2 February 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ a b c "El peor arranque de un gobierno en los últimos años: ningún presidente nombró tantos PCM en sus primeros 6 meses de gestión" [The worst start of a government in recent years: no president has appointed so many prime ministers in his first 6 months in office.]. RPP (in Spanish). 8 February 2022.

- ^ "Congreso no admite a debate moción de vacancia contra Pedro Castillo". La Republica (in Spanish). 7 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "Peru's president avoids impeachment after marathon debate". Al Jazeera. 28 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ "Peru Imposes Curfew to Stymie Protests Over Rising Fuel Costs". Reuters. 4 April 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ "Analysis: Peru's Castillo hardens stance on mining protests as economy stumbles". Reuters. 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Peru Congress backs motion to start impeachment against Castillo". Reuters. 2 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ a b Collyns, Dan (7 December 2022). "Peru's president reportedly detained and accused of sedition". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Taj, Mitra (7 December 2022). "Peru's President Quickly Ousted After Moving to Dissolve Congress". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ BRICEÑO, FRANKLIN; GARCIA CANO, REGINA (12 December 2022). "Anger in rural areas fuels protests against Peru government". AP News. ABC News. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ "Peru protests grow despite new president's early election pledge". Al Jazeera English. 12 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Miseria rural impulsa candidatura de maestro en Perú". Associated Press. 18 April 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Students' struggles pushed Peru teacher to run for president". Associated Press. 18 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Santaeulalia, Inés; Fowks, Jacqueline (12 April 2021). "Perú se encamina a una lucha por la presidencia entre el radical Pedro Castillo y Keiko Fujimori". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Quesada, Juan Diego (10 June 2021). "Pedro Castillo, the barefoot candidate poised to become the next president of Peru". El País. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Elecciones 2021: Conoce el perfil de Pedro Castillo, candidato del partido Perú Libre". andina.pe (in Spanish). 26 January 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d Samon Ros, Carla (5 June 2021). "Las humildes raíces del campesino que aspira a la presidencia del Perú". EFE (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Castillo, Pedro (24 June 2021). "Peru's Socialist President-Elect, Pedro Castillo, in His Own Words". Jacobin. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo is on the verge of becoming Peru's president". The Economist. 10 June 2021. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Pedro Castillo: Habrá minería "donde la naturaleza y la población la permitan"". Energiminas (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Acosta, Sebastián (8 April 2021). "Pedro Castillo cerró su campaña con un mitin en la Plaza Dos de Mayo". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Inequality fuels rural teacher's unlikely bid to upend Peru". Buenos Aires Times. Bloomberg. 3 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Asensio et al. 2021, pp. 27–71.

- ^ Herrada, Diego Pajares (23 December 2020). "Elecciones 2021: Pedro Castillo, el dirigente magisterial que busca hacerse un lugar desde la izquierda [Perfil] El Poder en tus Manos". rpp.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Elecciones 2021: Conoce a Pedro Castillo, candidato a la presidencia por Perú Libre". canaln.pe (in Spanish). 10 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Cusco: Sute anuncia medidas extremas si gobierno no atiende sus reclamos". larepublica.pe (in Spanish). 3 July 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Minedu: huelga de maestros tuvo mayor impacto solo en cinco regiones". El Comercio Perú (in Spanish). 13 July 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Acosta, Sebastián (3 August 2017). "Martens: "Hemos logrado adelantar el aumento salarial a S/2,000 para diciembre"". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Mininter: Pedro Castillo del Conare es cercano al Movadef y se presentarán pruebas en el Congreso". Gestión (in Spanish). 17 August 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "¿Cuál es el vínculo de Pedro Castillo con el Movadef, según Carlos Basombrío?". El Comercio (in Spanish). 22 August 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Benavides, Alan (6 August 2017). "Huelga de Maestros: Con descuentos o despidos, la huelga continúa". La Plaza (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Huelga de profesores: conoce los nuevos beneficios oficializados para los docentes". larepublica.pe (in Spanish). 23 August 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Marilú Martens ratifica que continuará contratación de nuevos maestros". El Comercio (in Spanish). 26 August 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo anuncia el fin de la huelga de profesores". larepublica.pe (in Spanish). 3 July 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Huelga de docentes fue suspendida temporalmente". El Comercio (in Spanish). 2 September 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ a b Asensio et al. 2021, pp. 13–24.

- ^ a b Asensio et al. 2021, p. 40.

- ^ a b Stefanoni, Pablo (8 March 2023). ""Que se vayan todos", otra vez, en Perú". CETRI (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo asegura que indultará a Antauro Humala si es elegido presidente". Gestión (in Spanish). 12 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "Perú: insurgentes se rinden" [Peru: insurgents surrender] (in Spanish). BBC News. 4 January 2005. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ O'Boyle, Brendan (3 May 2021). "Pedro Castillo and the 500-Year-Old Lima vs Rural Divide". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Collyns, Dan (12 April 2021). "Peru faces polarizing presidential runoff as teacher takes voters by surprise". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "Candidato más votado en Perú ofrece dialogar con otros partidos" (in Spanish). Deutsche Welle. 14 April 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo descartó la posibilidad de una hoja de ruta para la segunda vuelta nndc". Gestión (in Spanish). 14 April 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Pedro Castillo y Verónika Mendoza firman acuerdo de respaldo para la segunda vuelta Elecciones 2021 Perú Libre Juntos por el Perú nndc". Gestión (in Spanish). 5 May 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Allen, Nicolas (1 June 2021). "Pedro Castillo Can Help End Neoliberalism in Peru". Jacobin. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Either way, it's bad news; Bello". The Economist. 17 April 2021. p. 31.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo: abuchean a candidato de Perú Libre durante paseo proselitista en Mesa Redonda". Correo (in Spanish). 23 April 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo fue abucheado durante su paso por Mesa Redonda". Lucidez.pe (in Spanish). 23 April 2021. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo es abucheado en Trujillo: 'No somos comunistas'". El Bocón (in Spanish). 23 April 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Perú Libre denuncia amenazas de muerte contra el candidato presidencial Pedro Castillo". Europa Press (in Spanish). 29 April 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Excandidato peruano amenazó de muerte a Pedro Castillo y es denunciado penalmente". El Universo (in Spanish). 9 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Asensio et al. 2021, pp. 69–71.

- ^ "Peru has a new president, its fifth in five years – who is Pedro Castillo? | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Scott, Michael (2 June 2021). "Pánico entre los empresarios de Perú ante posible victoria de la ultra izquierda" [Panic among Peruvian businessmen before a possible victory of the far-left]. Financial Times (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Asensio et al. 2021, pp. 13–21.

- ^ a b Taj, Mitra; Turkewitz, Julie (19 July 2021). "Pedro Castillo, Leftist Political Outsider, Wins Peru Presidency". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Peru Stocks Tumble as Presidential Vote Spooks Investors". Bloomberg News. 11 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Arnold, Tom; Cervantes, Maria; Jones, Marc (12 April 2021). "Update 2-Socialist surge in election spooks Peru's financial markets". Reuters. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "Peru Leftist's Aide Rejects Hugo Chavez Comparison: 'No Way'". Bloomberg News. 4 June 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "Líderes políticos reaccionan a la proclamación de Pedro Castillo como presidente electo de Perú" [Political leaders react to the proclamation of Pedro Castillo as president-elect of Peru]. CNN (in Spanish). CNN en Español. 20 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Peru's Pedro Castillo closes in on victory in presidential election". NBC News. 10 June 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Agence France-Presse (13 April 2021). "Evo Morales felicita victoria de Pedro Castillo: 'Ganó con nuestra propuesta'". Gestión (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Candidato peruano marca distancia de gobierno de Venezuela". Associated Press. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "2 polarizing populists vie in Peru's presidential runoff". Associated Press. 6 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "Presidentes de Colombia, Ecuador y Bolivia felicitan a Pedro Castillo por proclamación". Andina (in Spanish). 19 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Peru's Castillo strengthens ties with China, asks for faster vaccine supply". Reuters. 16 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ a b "In Peru, the Knives Are Already Out for Pedro Castillo". Jacobin. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Long, Gideon (1 February 2022). "Peruvian finance minister quits amid government chaos". Financial Times. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ a b Moncada, Andrea (2 February 2022). "What to Make of Peru's Latest Crisis Under Castillo". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "Peru swears in new President Pedro Castillo". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ Moncada, Andrea (2 August 2021). "Is Pedro Castillo's Presidency Already Doomed?". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Pedro Castillo: No soy un político. No fui entrenado para ser presidente". CNN (in Spanish). 25 January 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "Peru: Regierungskrise nach nur sieben Monaten im Amt". tagesschau.de (in German). Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Rochabrun, Marcelo (29 April 2022). "Peru's ruling party turns on Castillo; calls for president to step down in 2023". Reuters. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ "Peru Leftist's Aide Rejects Hugo Chavez Comparison: 'No Way'". Bloomberg News. 4 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "Las medidas que plantea Pedro Francke". Gestión (in Spanish). 3 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ @pcmperu (31 July 2021). "#COMUNICADO El presidente del Consejo..." (Tweet). Retrieved 25 June 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Peru: President announces US$24 million to be allocated to soup kitchens". Andina (in Spanish). 15 September 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Castillo lanza la segunda reforma agraria de Perú y remarca que no busca 'expropiar tierras ni afectar derechos'". Europa Press (in Spanish). 4 October 2021.

- ^ Moncada, Andrea (14 September 2021). "An Unlikely Gift to Peru's President". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo anuncia alza del sueldo mínimo a S/ 1,000 para trabajadores formales". Gestió (in Spanish). 10 November 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Peru's Economy Grew 11.4% in Third Quarter". Bloomberg. 21 November 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Peru says IMF sees leeway to hike taxes on mining sector -finance ministry". Reuters. 2 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Fuel protests prompt Lima curfew as Ukraine crisis touches South America". The Guardian. 5 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Pozzebon, Stefano; Shoichet, Catherine E. (7 April 2022). "Peru protests show the wide impact of Putin's war". CNN. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ a b Noriega, Carlos (4 April 2022). "Dura protesta en Perú por la suba de los precios". Pagina 12. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Perú aumenta salario mínimo tras protestas por alza de precios". Yahoo! (in Spanish). 4 April 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b Rochabrun, Marcelo (6 April 2022). "Peru's Castillo lifts Lima curfew after widespread defiance, anger". Reuters. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Paro de transportistas: las claves de un conflicto que no pudo ser resuelto por el Gobierno". Convoca (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ EFE (2 August 2021). "Perú, fundador del Grupo de Lima, cambia con Castillo postura sobre Venezuela" [Peru, founder of the Lima Group, changes with Castillo position on Venezuela]. El Nuevo Herald (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Peruvian foreign minister quits amid criticism for comments". AP NEWS. 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Peru's Foreign Policy is exercised at the service of peace, democracy and development". MENA Report. Al Bawaba. 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo: protestan en exteriores de hotel donde se alojará en Washington nndc". Gestión (in Spanish). 19 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ a b Stott, Michael (26 September 2021). "Peru's radical left government weighs bond issue after wooing investors". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ "Pedro Castillo se reúne con empresarios tras su llegada a Washington D.C." La Republica (in Spanish). 19 September 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ a b Psaledakis, Daphne (22 September 2021). "Developing nations' plea to world's wealthy at U.N.: stop vaccine hoarding". Reuters. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ "Peru: President suggests global agreement at UN ensuring universal access to vaccines". Andina (in Spanish). 21 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ "Peru's FM states Bolivia's access to the sea already provided for in treaty". MercoPress English. 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Castillo convocó a otros cinco presidentes sudamericanos a una reunión sobre los migrantes" [Castillo convened five South American presidents to a meeting about migrants] (in Spanish). Télam. 19 June 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "El Congreso de Perú impide a Castillo viajar a Colombia y asistir a la toma de posesión de Petro". 5 August 2022.

- ^ "El Congreso de Perú niega a Castillo el permiso para viajar a México aunque sí le deja acudir a Chile". 18 November 2022.

- ^ Castillo, Maria Elena (24 October 2021).Empresarios tranzan acciones contra Pedro Castillo Archived 7 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine La República. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- ^ "Poderes no santos: alianzas de ultraderecha en Latinoamérica". OjoPúblico (in Spanish). 14 November 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Cabral, Ernesto (12 January 2021). "Militares en retiro con discursos extremistas se vinculan a políticos para apoyar la vacancia". OjoPúblico (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "Grupos de ultraderecha profundizan discursos de odio y la violencia en el Bicentenario". Ojo Público (in Spanish). 15 August 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ "La extrema derecha emerge en la crispada coyuntura política de Perú". Público. 25 August 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "La Resistencia: la radiografía de un grupo violento". Peru21 (in Spanish). 18 July 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Perú: ultraderechismo y pedidos de "vacancia" a poco de iniciar el Gobierno de Pedro Castillo". France 24. 5 November 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Seguidores de Keiko Fujimori marchan a Palacio y atacan el coche de dos ministros con ellos dentro". El Mundo (in Spanish). 15 July 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Guillermo Bermejo presentó moción de censura contra Maricarmen Alva y la acusa de tener intenciones de desestabilizar el país". Infobae (in Spanish). 13 December 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b "El sombrero sin cabeza". IDL Reporteros. 3 December 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Peru's Keiko Fujimori backs long-shot effort to impeach President Castillo". Reuters. 19 November 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Peru's chief of staff stashed $20,000 in palace bathroom". BBC News. 24 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "Peru opposition moves to impeach President Pedro Castillo". Al Jazeera. 26 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Salazar Vega, Elizabeth (12 January 2021). "Reuniones paralelas del presidente Castillo pueden derivar en investigaciones administrativas y penales". OjoPúblico (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "¿Cuál es la relación entre Karelim López y Karem Roca?". La Republica (in Spanish). 4 December 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Karelim López: ¿la afortunada vida de una lobista?". El Búho (in Spanish). 9 December 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Juliana Oxenford arremete contra Cuarto Poder por "audio bomba": "No fue ni chispita mariposa"". La Republica (in Spanish). 6 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Congreso no admite a debate moción de vacancia contra Pedro Castillo". La Republica (in Spanish). 7 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Aquino, Marco (8 December 2021). "Peru's Castillo fends off Congress impeachment vote amid protests". Reuters. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ "Fujimoristas detrás de encuentro sobre la vacancia". La Republica (in Spanish). 14 February 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Alva sobre eventual asunción a la presidencia: 'Uno tiene que estar preparado para todo'". La Republica (in Spanish). 6 February 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Congreso: miembros de la oposición sostuvieron reunión para vacar al presidente Pedro Castillo". La Republica (in Spanish). 11 February 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Pleno del Congreso no aprueba moción de vacancia presidencial contra Pedro Castillo". RPP (in Spanish). 28 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ "Peru: Case against Castillo reopened despite immunity". MercoPress. 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Pronunciamiento ante crisis política". Defensoria del Pueblo – Perú (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Spinetto, Juan Pablo (7 December 2022). "Peru Constitutional Court Calls Castillo's Dissolution of Congress a Coup". Bloomberg. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Taj, Mitra (7 December 2022). "Peru's President, Facing Impeachment, Says He Will Dissolve Congress". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Tegel, Simeon; Durán, Diana (7 December 2022). "Peru's congress impeaches president after he tries to dissolve it". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ "Peru: Pedro Castillo detained by police after coup attempt". MercoPress. 7 December 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Aquino, Marco; Hilaire, Valentine; Morland, Sarah (7 December 2022). "Peru's president detained by security forces- national police tweet". Reuters. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Aquino, Marco (8 December 2022). "Peru's Castillo detained in same jail as ex-leader Fujimori, source says". Reuters. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Quesada, Juan Diego (9 December 2022). "Inside the coup in Peru: 'President, what have you done?'". EL PAÍS English Edition. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Associated Press (AP) (24 April 2023). "Perú: Alejandro Toledo ya comparte la misma prisión que Alberto Fujimori y Pedro Castillo" [Peru: Alejandro Toledo already shares the same prison with Alberto Fujimori and Pedro Castillo]. Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "Peru - President Addresses General Debate, 78th Session | UN Web TV". media.un.org. 19 September 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Peru President Boluarte talks trade boost after meeting China's Xi". Reuters. 16 November 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Peru swears in VP as the new president amid constitutional crisis". PBS NewsHour. 7 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ "Peru: Statement by the Spokesperson on latest political developments | EEAS". www.eeas.europa.eu. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Reaction in Americas region to ousting of Peru's Castillo". Reuters. 8 December 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "After Mexico president backs Peru's Castillo, Boluarte to call leaders". Reuters. 13 December 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ "Colombia, Argentina, México y Bolivia, a favor de Castillo". Associated Press. 12 December 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ "Peru recalls ambassador to Honduras for 'unacceptable interference' as diplomatic spat deepens". Reuters. 26 January 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ Tegel, Simeon (13 December 2022). "Peru's Castillo says he's still president; international allies agree". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ "Peruvian President jailed after attempting "self-coup"". The Brazilian Report. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Pedro Castillo arremete contra Nicolás Maduro: 'que primero arregle sus problemas internos y que se lleve a sus compatriotas que vinieron a delinquir'". Diario Expreso. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Far left candidate Pedro Castillo leads Peruvian presidential race – Ipsos fast count". Reuters. 12 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Taj, Mitra (12 April 2021). "Peru Election for the 5th President in 5 Years Goes to Runoff". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Peru's socialists cheer election win as conservatives pledge to fight on". Reuters. 13 June 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Muñoz, Paula (July 2021). "Latin America Erupts: Peru Goes Populist". Journal of Democracy. 32 (3): 48–62. doi:10.1353/jod.2021.0033. S2CID 238828588. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Tegel, Simeon (14 May 2021). "Peru is Officially Investigating If Bleach Can Cure Covid". Vice. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

... two autocratic and socially conservative candidates who each routinely flout social distancing at their campaign rallies and appear to have a shaky grasp of the science around the pandemic.

- ^ "'We are not communists': Castillo seeks to allay fears in divided Peru". Reuters. 16 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ Gimeno, Fernando (4 June 2021). "Peru election pits 2 candidates opposed by women's rights, LGBT+ activists". La Prensa Latina Media. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

two socially conservative candidates that oppose abortion, same-sex marriage and gender equality-based education.

- ^ a b c Puente, Javier (14 April 2021). "Who is Peru's Frontrunner Pedro Castillo?". North American Congress on Latin America. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Pedro Castillo está en contra del enfoque de género en el currículo escolar". Gestion (in Spanish). 7 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Pedro Castillo, el maestro con el que se identifica el otro Perú". France 24. 12 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.