Oxytocin: Difference between revisions

→Peripheral (hormonal) actions: removed redundant URLs (link already provided from PMID field) |

|||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

* The relationship between oxytocin and human sexual response is unclear. At least two non-controlled studies have found increases in [[blood plasma|plasma]] oxytocin at orgasm – in both men and women.<ref name="carm1987">{{cite journal | author = Carmichael MS, Humbert R, Dixen J, Palmisano G, Greenleaf W, Davidson JM | title = Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response | journal = J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. | volume = 64 | issue = 1 | pages = 27–31 | year = 1987 | month = January | pmid = 3782434 | doi = | url = | issn = | accessdate = 15 September 2009}}</ref><ref name="pmid8135652">{{cite journal | author = Carmichael MS, Warburton VL, Dixen J, Davidson JM | title = Relationships among cardiovascular, muscular, and oxytocin responses during human sexual activity | journal = Arch Sex Behav | volume = 23 | issue = 1 | pages = 59–79 | year = 1994 | month = February | pmid = 8135652 | doi = | url = | issn = }}</ref> Plasma oxytocin levels are notably increased around the time of self stimulated orgasm and are still higher than baseline when measured 5 minutes after self arousal.<ref name="carm1987" /> The authors of one of these studies speculated that oxytocin's effects on muscle contractibility may facilitate sperm and egg transport.<ref name="carm1987" /> In a study that measured oxytocin serum levels in women before and after sexual stimulation the author suggests that oxytocin serves an important role in sexual arousal. This study found that that genital tract stimulation resulted in increased oxytocin immediately after orgasm. <ref name="Blaicher1999">{{cite journal | author = Blaicher W, Gruber D, Bieglmayer C, Blaicher AM, Knogler W & Huber JC.| title = The role of oxytocin in relation to female sexual arousal | journal = Gynecologic Obstetric Investigation | volume = 47 | pages = 125-126 | year = 1999 | pmid = 9949283 | doi = 10.1159/000010075 | url = }}</ref> Another study that reports increases of oxytocin during sexual arousal states that it could be in response to nipple/areola, genital, and/or genital tract stimulation as confirmed in other mammals.<ref name="Andersonhunt1995">{{cite journal | author = Anderson-Hunt M | title = Oxytocin and female sexuality. | journal = Gynecologic Obstetric Investigation | volume = 40 | issue = 4 | pages = 217-221 | year = 1995 | pmid = 8586300 | doi = | url = }}</ref> Murphy et al. (1987), studying men, found that oxytocin levels were raised throughout sexual arousal and there was no acute increase at orgasm.<ref name="pmid3654918">{{cite journal | author = Murphy MR, Seckl JR, Burton S, Checkley SA, Lightman SL | title = Changes in oxytocin and vasopressin secretion during sexual activity in men | journal = J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. | volume = 65 | issue = 4 | pages = 738–41 | year = 1987 | month = October | pmid = 3654918 | doi = | url = | issn = }}</ref> A more recent study of men found an increase in plasma oxytocin immediately after orgasm, but only in a portion of their sample that did not reach statistical significance. The authors noted that these changes "may simply reflect contractile properties on reproductive tissue."<ref name="pmid12697037">{{cite journal | author = Krüger TH, Haake P, Chereath D, Knapp W, Janssen OE, Exton MS, Schedlowski M, Hartmann U | title = Specificity of the neuroendocrine response to orgasm during sexual arousal in men | journal = J. Endocrinol. | volume = 177 | issue = 1 | pages = 57–64 | year = 2003 | month = April | pmid = 12697037 | doi = 10.1677/joe.0.1770057 | url = | issn = }}</ref> |

* The relationship between oxytocin and human sexual response is unclear. At least two non-controlled studies have found increases in [[blood plasma|plasma]] oxytocin at orgasm – in both men and women.<ref name="carm1987">{{cite journal | author = Carmichael MS, Humbert R, Dixen J, Palmisano G, Greenleaf W, Davidson JM | title = Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response | journal = J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. | volume = 64 | issue = 1 | pages = 27–31 | year = 1987 | month = January | pmid = 3782434 | doi = | url = | issn = | accessdate = 15 September 2009}}</ref><ref name="pmid8135652">{{cite journal | author = Carmichael MS, Warburton VL, Dixen J, Davidson JM | title = Relationships among cardiovascular, muscular, and oxytocin responses during human sexual activity | journal = Arch Sex Behav | volume = 23 | issue = 1 | pages = 59–79 | year = 1994 | month = February | pmid = 8135652 | doi = | url = | issn = }}</ref> Plasma oxytocin levels are notably increased around the time of self stimulated orgasm and are still higher than baseline when measured 5 minutes after self arousal.<ref name="carm1987" /> The authors of one of these studies speculated that oxytocin's effects on muscle contractibility may facilitate sperm and egg transport.<ref name="carm1987" /> In a study that measured oxytocin serum levels in women before and after sexual stimulation the author suggests that oxytocin serves an important role in sexual arousal. This study found that that genital tract stimulation resulted in increased oxytocin immediately after orgasm. <ref name="Blaicher1999">{{cite journal | author = Blaicher W, Gruber D, Bieglmayer C, Blaicher AM, Knogler W & Huber JC.| title = The role of oxytocin in relation to female sexual arousal | journal = Gynecologic Obstetric Investigation | volume = 47 | pages = 125-126 | year = 1999 | pmid = 9949283 | doi = 10.1159/000010075 | url = }}</ref> Another study that reports increases of oxytocin during sexual arousal states that it could be in response to nipple/areola, genital, and/or genital tract stimulation as confirmed in other mammals.<ref name="Andersonhunt1995">{{cite journal | author = Anderson-Hunt M | title = Oxytocin and female sexuality. | journal = Gynecologic Obstetric Investigation | volume = 40 | issue = 4 | pages = 217-221 | year = 1995 | pmid = 8586300 | doi = | url = }}</ref> Murphy et al. (1987), studying men, found that oxytocin levels were raised throughout sexual arousal and there was no acute increase at orgasm.<ref name="pmid3654918">{{cite journal | author = Murphy MR, Seckl JR, Burton S, Checkley SA, Lightman SL | title = Changes in oxytocin and vasopressin secretion during sexual activity in men | journal = J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. | volume = 65 | issue = 4 | pages = 738–41 | year = 1987 | month = October | pmid = 3654918 | doi = | url = | issn = }}</ref> A more recent study of men found an increase in plasma oxytocin immediately after orgasm, but only in a portion of their sample that did not reach statistical significance. The authors noted that these changes "may simply reflect contractile properties on reproductive tissue."<ref name="pmid12697037">{{cite journal | author = Krüger TH, Haake P, Chereath D, Knapp W, Janssen OE, Exton MS, Schedlowski M, Hartmann U | title = Specificity of the neuroendocrine response to orgasm during sexual arousal in men | journal = J. Endocrinol. | volume = 177 | issue = 1 | pages = 57–64 | year = 2003 | month = April | pmid = 12697037 | doi = 10.1677/joe.0.1770057 | url = | issn = }}</ref> |

||

It is also important to note that more studies have been done to examine sexual arousal in women compared to men. Women experience longer orgasms compared to men [[Orgasm]], and have a more complex reproductive endocrine system with clearly identified cycles such as, menstruation, lactation, menopause, and pregnancy.<ref name="Bancroft2005">{{cite journal | author = Bancroft J | title = The endocrinology of sexual arousal. | journal = Journal of Endocrinology| volume = 187 | pages = 411-427 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16135662 | doi = 10.1677/joe.1.062330022-0795/05/0186-411 | url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16135662?itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum&ordinalpos=2}}</ref> This allows more opportunities to measure and examine the hormones related to sexual arousal. |

|||

Oxytocin evokes feelings of contentment, reductions in anxiety, and feelings of calmness and security around a mate.<ref>name="Meyer2007">{{cite journal | author = Meyer D | title = Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and their effects on relationship satisfaction. | journal = The Family Journal| volume = 15 | pages = 392-397 | year = 2007 | pmid = | doi = 10.1177/1066480707305470 | url = }}</ref>In order to reach full orgasm, it is necessary that brain regions associated with behavioral control, fear and anxiety are deactivated; which allows individuals to let go of fear and anxiety during sexual arousal[[Orgasm]]. Many studies have already shown a correlation of oxytocin with social bonding, increases in trust, and decreases in fear. One study confirmed that there was a positive correlation between oxytocin plasma levels and an anxiety scale measuring the adult romantic attachment.<ref>name="Marazziti2006">{{cite journal | author = Marazziti D, Dell’Osso B, Baroni S, Mungai F, Catena M, Rucci P, et al | title = A relationship between oxytocin and anxiety of romantic attachment. | journal = Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health| volume = 2| pages = 28 | year = 2006 | pmid = | doi = 10.1186/1745-0179-2-28 | url = }}</ref> This suggests that oxytocin may be important for the inhibition of brain regions that are associated with behavioral control, fear, and anxiety, thus allowing orgasm to occur. |

|||

* Due to its similarity to [[vasopressin]], it can reduce the excretion of [[urine]] slightly. In several species, oxytocin can stimulate sodium excretion from the kidneys (natriuresis), and in humans, high doses of oxytocin can result in [[hyponatremia]]. |

* Due to its similarity to [[vasopressin]], it can reduce the excretion of [[urine]] slightly. In several species, oxytocin can stimulate sodium excretion from the kidneys (natriuresis), and in humans, high doses of oxytocin can result in [[hyponatremia]]. |

||

Revision as of 06:08, 24 November 2009

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intranasal, IV, IM |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | nil |

| Protein binding | 30% |

| Metabolism | hepatic oxytocinases |

| Elimination half-life | 1–6 min |

| Excretion | Biliary and renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.045 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C43H66N12O12S2 |

| Molar mass | 1007.19 g/mol g·mol−1 |

Oxytocin (Template:Pron-en) (sold as Pitocin, Syntocinon) is a mammalian hormone that also acts as a neurotransmitter in the brain.

It is best known for its roles in female reproduction: it is released in large amounts after distension of the cervix and vagina during labor, and after stimulation of the nipples, facilitating birth and breastfeeding, respectively. Recent studies have begun to investigate oxytocin's role in various behaviors, including orgasm, social recognition, pair bonding, anxiety, trust, love, and maternal behaviors.[2]

Synthesis, storage and release

Oxytocin is made in magnocellular neurosecretory cells of the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus and is stored in Herring bodies at the axon terminals in the posterior pituitary. It is then released into the blood from the posterior lobe (neurohypophysis) of the pituitary gland. These axons (likely, but dendrites have not been ruled out) have collaterals that innervate oxytocin receptors in the nucleus accumbens.[3] The peripheral hormonal and behavioral brain effects of oxytocin it has been suggested are coordinated through its common release through these collaterals.[3] Oxytocin is also made by some neurons in the paraventricular nucleus that project to other parts of the brain and to the spinal cord.[4] Depending on the species, oxytocin-receptor expressing cells are located in other areas, including the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis.

In the pituitary gland, oxytocin is packaged in large, dense-core vesicles, where it is bound to neurophysin I as shown in the inset of the figure; neurophysin is a large peptide fragment of the larger precursor protein molecule from which oxytocin is derived by enzymatic cleavage.

Secretion of oxytocin from the neurosecretory nerve endings is regulated by the electrical activity of the oxytocin cells in the hypothalamus. These cells generate action potentials that propagate down axons to the nerve endings in the pituitary; the endings contain large numbers of oxytocin-containing vesicles, which are released by exocytosis when the nerve terminals are depolarised.

Oxytocin is also synthesized by corpora lutea of several species, including ruminants and primates. Along with estrogen, it is involved in inducing the endometrial synthesis of Prostaglandin-F2alpha to cause regression of the corpus luteum.

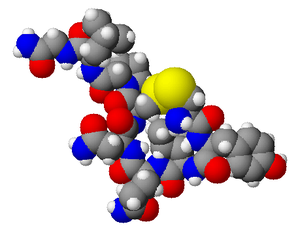

Structure and relation to vasopressin

Oxytocin is a peptide of nine amino acids (a nonapeptide). The sequence is cysteine - tyrosine - isoleucine - glutamine - asparagine - cysteine - proline - leucine - glycine (CYIQNCPLG). The cysteine residues form a sulfur bridge. Oxytocin has a molecular mass of 1007 daltons. One international unit (IU) of oxytocin is the equivalent of about 2 micrograms of pure peptide.

The structure of oxytocin is very similar to that of vasopressin (cysteine - tyrosine - phenylalanine - glutamine - asparagine - cysteine - proline - arginine - glycine), also a nonapeptide with a sulfur bridge, whose sequence differs from oxytocin by 2 amino acids. A table showing the sequences of members of the vasopressin/oxytocin superfamily and the species expressing them is present in the vasopressin article. Oxytocin and vasopressin were isolated and synthesized by Vincent du Vigneaud in 1953, work for which he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1955.

Oxytocin and vasopressin are the only known hormones released by the human posterior pituitary gland to act at a distance. However, oxytocin neurons make other peptides, including corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and dynorphin, for example, that act locally. The magnocellular neurons that make oxytocin are adjacent to magnocellular neurons that make vasopressin, and are similar in many respects.

Actions

| oxytocin, prepro- (neurophysin I) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | OXT | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | OT | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 5020 | ||||||

| HGNC | 8528 | ||||||

| OMIM | 167050 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_000915 | ||||||

| UniProt | P01178 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 20 p13 | ||||||

| |||||||

Oxytocin has peripheral (hormonal) actions, and also has actions in the brain. The actions of oxytocin are mediated by specific, high affinity oxytocin receptors. The oxytocin receptor is a G-protein-coupled receptor which requires Mg2+ and cholesterol. It belongs to the rhodopsin-type (class I) group of G-protein-coupled receptors.

Peripheral (hormonal) actions

The peripheral actions of oxytocin mainly reflect secretion from the pituitary gland. (See oxytocin receptor for more detail on its action.)

- Letdown reflex – in lactating (breastfeeding) mothers, oxytocin acts at the mammary glands, causing milk to be 'let down' into a collecting chamber, from where it can be extracted by compressing the areola and sucking at the nipple. Sucking by the infant at the nipple is relayed by spinal nerves to the hypothalamus. The stimulation causes neurons that make oxytocin to fire action potentials in intermittent bursts; these bursts result in the secretion of pulses of oxytocin from the neurosecretory nerve terminals of the pituitary gland.

- Uterine contraction – important for cervical dilation before birth and causes contractions during the second and third stages of labor. Oxytocin release during breastfeeding causes mild but often painful uterine contractions during the first few weeks of lactation. This also serves to assist the uterus in clotting the placental attachment point postpartum. However, in knockout mice lacking the oxytocin receptor, reproductive behavior and parturition is normal.[5]

- The relationship between oxytocin and human sexual response is unclear. At least two non-controlled studies have found increases in plasma oxytocin at orgasm – in both men and women.[6][7] Plasma oxytocin levels are notably increased around the time of self stimulated orgasm and are still higher than baseline when measured 5 minutes after self arousal.[6] The authors of one of these studies speculated that oxytocin's effects on muscle contractibility may facilitate sperm and egg transport.[6] In a study that measured oxytocin serum levels in women before and after sexual stimulation the author suggests that oxytocin serves an important role in sexual arousal. This study found that that genital tract stimulation resulted in increased oxytocin immediately after orgasm. [8] Another study that reports increases of oxytocin during sexual arousal states that it could be in response to nipple/areola, genital, and/or genital tract stimulation as confirmed in other mammals.[9] Murphy et al. (1987), studying men, found that oxytocin levels were raised throughout sexual arousal and there was no acute increase at orgasm.[10] A more recent study of men found an increase in plasma oxytocin immediately after orgasm, but only in a portion of their sample that did not reach statistical significance. The authors noted that these changes "may simply reflect contractile properties on reproductive tissue."[11]

It is also important to note that more studies have been done to examine sexual arousal in women compared to men. Women experience longer orgasms compared to men Orgasm, and have a more complex reproductive endocrine system with clearly identified cycles such as, menstruation, lactation, menopause, and pregnancy.[12] This allows more opportunities to measure and examine the hormones related to sexual arousal. Oxytocin evokes feelings of contentment, reductions in anxiety, and feelings of calmness and security around a mate.[13]In order to reach full orgasm, it is necessary that brain regions associated with behavioral control, fear and anxiety are deactivated; which allows individuals to let go of fear and anxiety during sexual arousalOrgasm. Many studies have already shown a correlation of oxytocin with social bonding, increases in trust, and decreases in fear. One study confirmed that there was a positive correlation between oxytocin plasma levels and an anxiety scale measuring the adult romantic attachment.[14] This suggests that oxytocin may be important for the inhibition of brain regions that are associated with behavioral control, fear, and anxiety, thus allowing orgasm to occur.

- Due to its similarity to vasopressin, it can reduce the excretion of urine slightly. In several species, oxytocin can stimulate sodium excretion from the kidneys (natriuresis), and in humans, high doses of oxytocin can result in hyponatremia.

- Oxytocin and oxytocin receptors are also found in the heart in some rodents, and the hormone may play a role in the embryonal development of the heart by promoting cardiomyocyte differentiation.[15][16] However, the absence of either oxytocin or its receptor in knockout mice has not been reported to produce cardiac insufficiencies.[5]

- Modulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Oxytocin, under certain circumstances, indirectly inhibits release of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol and, in those situations, may be considered an antagonist of vasopressin.[17]

Actions of oxytocin within the brain

Oxytocin secreted from the pituitary gland cannot re-enter the brain because of the blood-brain barrier. Instead, the behavioral effects of oxytocin are thought to reflect release from centrally projecting oxytocin neurons, different from those that project to the pituitary gland, or which are collaterals from them.[3] Oxytocin receptors are expressed by neurons in many parts of the brain and spinal cord, including the amygdala, ventromedial hypothalamus, septum, nucleus accumbens and brainstem.

- Sexual arousal. Oxytocin injected into the cerebrospinal fluid causes spontaneous erections in rats,[18] reflecting actions in the hypothalamus and spinal cord.

- Bonding. In the Prairie Vole, oxytocin released into the brain of the female during sexual activity is important for forming a monogamous pair bond with her sexual partner. Vasopressin appears to have a similar effect in males.[19] Oxytocin has a role in social behaviors in many species, and so it seems likely that it has similar roles in humans.

- Autism. Oxytocin may play a role in autism and may be an effective treatment for autism's repetitive and affiliative behaviors.[20] Oxytocin treatments also resulted in an increased retention of affective speech in adults with autism.[21] Two related studies in adults, in 2003 and 2007, found that oxytocin decreased repetitive behaviors and improved interpretation of emotions, but these preliminary results do not necessarily apply to children.[22]

- Maternal behavior. Rat females given oxytocin antagonists after giving birth do not exhibit typical maternal behavior.[23] By contrast, virgin female sheep show maternal behavior towards foreign lambs upon cerebrospinal fluid infusion of oxytocin, which they would not do otherwise.[24]

- Increasing trust and reducing fear. In a risky investment game, experimental subjects given nasally administered oxytocin displayed "the highest level of trust" twice as often as the control group. Subjects who were told that they were interacting with a computer showed no such reaction, leading to the conclusion that oxytocin was not merely affecting risk-aversion.[25] Nasally administered oxytocin has also been reported to reduce fear, possibly by inhibiting the amygdala (which is thought to be responsible for fear responses).[26] There is no conclusive evidence for access of oxytocin to the brain through intranasal administration, however.

- Affecting generosity by increasing empathy during perspective taking. In a neuroeconomics experiment, intranasal oxytocin increased generosity in the Ultimatum Game by 80% but has no effect in the Dictator Game that measures altruism. Perspective-taking is not required in the Dictator Game, but the researchers in this experiment explicitly induced perspective-taking in the Ultimatum Game by not identifying to participants which role they would be in.[27]

- According to some studies in animals, oxytocin inhibits the development of tolerance to various addictive drugs (opiates, cocaine, alcohol) and reduces withdrawal symptoms.[28]

- Preparing fetal neurons for delivery. Crossing the placenta, maternal oxytocin reaches the fetal brain and induces a switch in the action of neurotransmitter GABA from excitatory to inhibitory on fetal cortical neurons. This silences the fetal brain for the period of delivery and reduces its vulnerability to hypoxic damage.[29]

- Certain learning and memory functions are impaired by centrally administered oxytocin.[18] Also, systemic oxytocin administration can impair memory retrieval in certain aversive memory tasks.[30]

- MDMA (ecstasy) may increase feelings of love, empathy and connection to others by stimulating oxytocin activity via activation of serotonin 5-HT1A receptors, if initial studies in animals apply to humans.[31]

Drug forms

Synthetic oxytocin is sold as medication under the trade names Pitocin and Syntocinon and also as generic oxytocin. Oxytocin is destroyed in the gastrointestinal tract, and therefore must be administered by injection or as nasal spray. Oxytocin has a half-life of typically about three minutes in the blood. Oxytocin given intravenously does not enter the brain in significant quantities - it is excluded from the brain by the blood-brain barrier. There is no evidence for significant CNS entry of oxytocin by nasal spray. Oxytocin nasal sprays have been used to stimulate breastfeeding but the efficacy of this approach is doubtful.[32]

Injected oxytocin analogues are used to induce labor and support labor in case of non-progression of parturition. It has largely replaced ergometrine as the principal agent to increase uterine tone in acute postpartum haemorrhage. Oxytocin is also used in veterinary medicine to facilitate birth and to increase milk production. The tocolytic agent atosiban (Tractocile) acts as an antagonist of oxytocin receptors; this drug is registered in many countries to suppress premature labour between 24 and 33 weeks of gestation. It has fewer side-effects than drugs previously used for this purpose (ritodrine, salbutamol and terbutaline). Some have suggested that the trust-inducing property of oxytocin might help those who suffer from social anxieties and mood disorders, while others have noted the potential for abuse with confidence tricks[33][34] and military applications.[35]

Potential adverse reactions

Oxytocin is relatively safe when used at recommended doses. Potential side effects include:[citation needed]

- Central nervous system: Subarachnoid hemorrhage, seizures.

- Cardiovascular: Increased heart rate, decreased blood pressure, systemic venous return, cardiac output, and arrhythmias.

- Genitourinary: Impaired uterine blood flow, pelvic hematoma, tetanic uterine contractions, uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage.

- Fetal distress: Overstimulated uterus, too frequent contractions, resulting in reduced ability of placenta/fetus to re-oxygenate and process waste products. This increases chances of Caesarean section.

Evolution

Virtually all vertebrates have an oxytocin-like nonapeptide hormone that supports reproductive functions and a vasopressin-like nonapeptide hormone involved in water regulation. The two genes are usually located close to each other (less than 15,000 bases apart) on the same chromosome and are transcribed in opposite directions (however, for example, see[36] for fugu).

It is thought that the two genes resulted from a gene duplication event; the ancestral gene is estimated to be about 500 million years old and is found in cyclostomes (modern members of the Agnatha).[18]

See also

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Lee HJ, Macbeth AH, Pagani JH, Young WS (2009). "Oxytocin: the great facilitator of life". Prog. Neurobiol. 88 (2): 127–51. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.04.001. PMID 19482229.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Ross HE, Cole CD, Smith Y, Neumann ID, Landgraf R, Murphy AZ, Young LJ (2009). "Characterization of the oxytocin system regulating affiliative behavior in female prairie voles". Neuroscience. 162 (4): 892–903. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.055. PMID 19482070.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Landgraf R, Neumann ID. (2004). Vasopressin and oxytocin release within the brain: a dynamic concept of multiple and variable modes of neuropeptide communication. Front Neuroendocrinol. 25(3-4):150-76. PMID 15589267

- ^ a b Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, Yanagisawa T, Kimura T, Matzuk MM, Young LJ, Nishimori K (2005). "Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (44): 16096–101. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505312102. PMC 1276060. PMID 16249339.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Carmichael MS, Humbert R, Dixen J, Palmisano G, Greenleaf W, Davidson JM (1987). "Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 64 (1): 27–31. PMID 3782434.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carmichael MS, Warburton VL, Dixen J, Davidson JM (1994). "Relationships among cardiovascular, muscular, and oxytocin responses during human sexual activity". Arch Sex Behav. 23 (1): 59–79. PMID 8135652.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blaicher W, Gruber D, Bieglmayer C, Blaicher AM, Knogler W & Huber JC. (1999). "The role of oxytocin in relation to female sexual arousal". Gynecologic Obstetric Investigation. 47: 125–126. doi:10.1159/000010075. PMID 9949283.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anderson-Hunt M (1995). "Oxytocin and female sexuality". Gynecologic Obstetric Investigation. 40 (4): 217–221. PMID 8586300.

- ^ Murphy MR, Seckl JR, Burton S, Checkley SA, Lightman SL (1987). "Changes in oxytocin and vasopressin secretion during sexual activity in men". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 65 (4): 738–41. PMID 3654918.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krüger TH, Haake P, Chereath D, Knapp W, Janssen OE, Exton MS, Schedlowski M, Hartmann U (2003). "Specificity of the neuroendocrine response to orgasm during sexual arousal in men". J. Endocrinol. 177 (1): 57–64. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1770057. PMID 12697037.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bancroft J (2005). "The endocrinology of sexual arousal". Journal of Endocrinology. 187: 411–427. doi:10.1677/joe.1.062330022-0795/05/0186-411. PMID 16135662.

- ^ name="Meyer2007">Meyer D (2007). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and their effects on relationship satisfaction". The Family Journal. 15: 392–397. doi:10.1177/1066480707305470.

- ^ name="Marazziti2006">Marazziti D, Dell’Osso B, Baroni S, Mungai F, Catena M, Rucci P; et al. (2006). "A relationship between oxytocin and anxiety of romantic attachment". Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2: 28. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-2-28.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Paquin J, Danalache BA, Jankowski M, McCann SM, Gutkowska J (2002). "Oxytocin induces differentiation of P19 embryonic stem cells to cardiomyocytes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (14): 9550–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.152302499. PMC 123178. PMID 12093924.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jankowski M, Danalache B, Wang D, Bhat P, Hajjar F, Marcinkiewicz M, Paquin J, McCann SM, Gutkowska J (2004). "Oxytocin in cardiac ontogeny". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (35): 13074–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405324101. PMC 516519. PMID 15316117.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hartwig, Walenty (1989). Endokrynologia praktyczna. Warszawa: Pa℗nst. Zaka̜d Wydawnictw Lekarskich. ISBN 83-200-1415-8.

- ^ a b c Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F (2001). "The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation". Physiol. Rev. 81 (2): 629–83. PMID 11274341.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Vacek M, High on Fidelity. What can voles teach us about monogamy?

- ^ Bartz JA, Hollander E (2008). "Oxytocin and experimental therapeutics in autism spectrum disorders". Prog Brain Res. 170 (451–62): 451. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00435-4. PMID 18655901.

- ^ Jacob S, Brune CW, Carter CS, Leventhal BL, Lord C, Cook EH Jr. (2007). "Association of the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) in Caucasian children and adolescents with autism". Neuroscience Letters. 417 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.001. PMID 17383819.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Opar A (2008). "Search for potential autism treatments turns to 'trust hormone'". Nat Med. 14 (4): 353. doi:10.1038/nm0408-353. PMID 18391923.

- ^ van Leengoed E, Kerker E, Swanson HH (1987). "Inhibition of post-partum maternal behaviour in the rat by injecting an oxytocin antagonist into the cerebral ventricles". J. Endocrinol. 112 (2): 275–82. doi:10.1677/joe.0.1120275. PMID 3819639.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kendrick KM (2004-01-01). "The Neurobiology of Social Bonds". British Society for Neuroendocrinology. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E (2005). PDF "Oxytocin increases trust in humans". Nature. 435 (7042): 673–6. doi:10.1038/nature03701. PMID 15931222.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kirsch P, Esslinger C, Chen Q, Mier D, Lis S, Siddhanti S, Gruppe H, Mattay VS, Gallhofer B, Meyer-Lindenberg A (2005). "Oxytocin modulates neural circuitry for social cognition and fear in humans". J. Neurosci. 25 (49): 11489–93. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3984-05.2005. PMID 16339042.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zak PJ, Stanton AA, Ahmadi S (2007). "Oxytocin increases generosity in humans". PLoS ONE. 2 (11): e1128. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001128. PMC 2040517. PMID 17987115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kovács GL, Sarnyai Z, Szabó G (1998). "Oxytocin and addiction: a review". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 23 (8): 945–62. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00064-X. PMID 9924746.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tyzio R, Cossart R, Khalilov I, Minlebaev M, Hübner CA, Represa A, Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R (2006). "Maternal oxytocin triggers a transient inhibitory switch in GABA signaling in the fetal brain during delivery". Science (journal). 314 (5806): 1788–92. doi:10.1126/science.1133212. PMID 17170309.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de Oliveira LF, Camboim C, Diehl F, Consiglio AR, Quillfeldt JA (2007). "Glucocorticoid-mediated effects of systemic oxytocin upon memory retrieval". Neurobiol Learn Mem. 87 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2006.05.006. PMID 16997585.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thompson MR, Callaghan PD, Hunt GE, Cornish JL, McGregor IS (2007). "A role for oxytocin and 5-HT(1A) receptors in the prosocial effects of 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine ("ecstasy")". Neuroscience. 146 (2): 509–14. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.032. PMID 17383105.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fewtrell MS, Loh KL, Blake A, Ridout DA, Hawdon J (2006). "Randomised, double blind trial of oxytocin nasal spray in mothers expressing breast milk for preterm infants". Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 91 (3): F169–74. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.081265. PMID 16223754.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Petrovic P, Kalisch R, Singer T, Dolan RJ (2008). "Oxytocin attenuates affective evaluations of conditioned faces and amygdala activity". J. Neurosci. 28 (26): 6607–15. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4572-07.2008. PMC 2647078. PMID 18579733.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "To sniff at danger - Mind Matters". Health And Fitness. Boston Globe. 2006-01-12. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Dando M (2009). "Biologists napping while work militarized". Nature. 460 (7258): 950–1. doi:10.1038/460950a. PMID 19693065.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Venkatesh B, Si-Hoe SL, Murphy D, Brenner S (1997). "Transgenic rats reveal functional conservation of regulatory controls between the Fugu isotocin and rat oxytocin genes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (23): 12462–6. PMC 25001. PMID 9356472.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Lee HJ, Macbeth AH, Pagani JH, Young WS (2009). "Oxytocin: the great facilitator of life". Prog. Neurobiol. 88 (2): 127–51. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.04.001. PMID 19482229.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Caldwell HK, Young WS III (2006). "Oxytocin and Vasopressin: Genetics and Behavioral Implications". In Abel L, Lim R (ed.). Handbook of neurochemistry and molecular neurobiology (PDF). Berlin: Springer. pp. 573–607. ISBN 0-387-30348-0.

External links

- New Scientist -'Cuddle chemical' could treat mental illness (14 May 2008)

- NewScientist.com - 'Release of Oxytocin due to penetrative sex reduces stress and neurotic tendencies', New Scientist (January 26, 2006)

- Oxytocin.org - 'I get a kick out of you: Scientists are finding that, after all, love really is down to a chemical addiction between people', The Economist (February 12, 2004)

- SMH.com.au - 'To sniff at danger: Inhalable oxytocin could become a cure for social fears', Boston Globe (January 12, 2006)

- Hug the Monkey - A weblog devoted entirely to oxytocin

- A Neurophysiologic Model of the Circuitry of Oxytocin in Arousal, Female Distress and Depression - Rainer K. Liedtke, MD