Finasteride: Difference between revisions

→Sexual side effects: typo |

→Male pattern baldness: template ref |

||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

===Male pattern baldness=== |

===Male pattern baldness=== |

||

Finasteride is used to treat male pattern hair loss ([[androgenetic alopecia]]) in men only.<ref name=PropeciaLabel>{{cite web |url=http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/020788s024lbl.pdf |title=www.accessdata.fda.gov |title=Propecia label}}</ref> Treatment provides about 30% improvement in hair loss after six months of treatment, and effectiveness only persists as long as the drug is taken.<ref name=2014AArev>Varothai |

Finasteride is used to treat male pattern hair loss ([[androgenetic alopecia]]) in men only.<ref name=PropeciaLabel>{{cite web |url=http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/020788s024lbl.pdf |title=www.accessdata.fda.gov |title=Propecia label}}</ref> Treatment provides about 30% improvement in hair loss after six months of treatment, and effectiveness only persists as long as the drug is taken.<ref name=2014AArev>{{cite journal|last1=Varothai|first1=S|last2=Bergfeld|first2=WF|title=Androgenetic alopecia: an evidence-based treatment update.|journal=American journal of clinical dermatology|date=2014 Jul|volume=15|issue=3|pages=217-30|doi=10.1007/s40257-014-0077-5|pmid=24848508}}</ref> |

||

===Off-label uses=== |

===Off-label uses=== |

||

Revision as of 21:33, 27 October 2014

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Propecia, Proscar |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a698016 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 63% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | Elderly: 8 hours Adults: 6 hours |

| Excretion | Feces (57%) and urine (39%) as metabolites |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.149.445 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

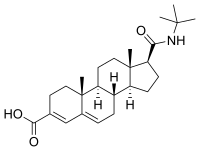

| Formula | C23H36N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 372.549 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Finasteride (MK-906, Proscar and Propecia by Merck, among other generic names) is a drug for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and male pattern baldness (MPB). It is a type II 5α-reductase inhibitor. 5α-reductase is an enzyme that converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT).

Medical uses

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Physicians use finasteride for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), informally known as an enlarged prostate. The FDA-approved dose is 5 mg once a day. Six months or more of treatment with finasteride may be required to determine the therapeutic results of treatment. If the drug is discontinued, any therapeutic benefits reverse within about 6–8 months. Finasteride may improve the symptoms associated with BPH such as difficulty urinating, getting up during the night to urinate, hesitation at the start of urination, and decreased urinary flow.[1][2]

Male pattern baldness

Finasteride is used to treat male pattern hair loss (androgenetic alopecia) in men only.[3] Treatment provides about 30% improvement in hair loss after six months of treatment, and effectiveness only persists as long as the drug is taken.[4]

Off-label uses

Finasteride is sometimes used in hormone replacement therapy for male-to-female transsexuals in combination with a form of estrogen due to its antiandrogen properties. However, little clinical research of finasteride use for this purpose has been conducted and evidence of efficacy is limited.[5]

Contraindications

Finasteride is not approved for use in woman, especially due to risks of birth defects in a fetus. It is classified in the FDA pregnancy category X.[3]

Adverse effects

Side effects include increased risk of prostate cancer, reduced levels of prostate specific antigen (PSA) which could mask an increase in levels of PSA, which is used clinically a diagnostic test for prostate cancer, and sexual dysfunction. There may be a risk of breast cancer and mood disorders.

Prostate cancer

The FDA has added a warning to 5α-reductase inhibitors concerning an increased risk of high-grade prostate cancer.[6] While the effect of finasteride on the risk of developing prostate cancer has not been established, evidence suggests it may temporarily reduce the growth and prevalence of benign prostate tumors, but could also mask the early detection of prostate cancer. The primary concern is patients who develop prostate cancer while taking finasteride for benign prostatic hyperplasia, which in turn could delay diagnosis and early treatment of the prostate cancer, thereby potentially increasing the risk of these patients developing high-grade prostate cancer.[7]

Sexual side effects

Two meta analyses have been conducted that explore the subject of sexual side effects caused by finasteride. One study found that active intervention with finasteride did not significantly differ from placebo in eliciting sexual dysfunction while the other suggested daily use of oral finasteride increase the risk of sexual dysfunction.[8][9]

There are case reports of persistent diminished libido or erectile dysfunction even after stopping the drug; the prevalence is not known.[4][10]

Anxiety and depression

Mood disorders were not observed as an important adverse effect in the phase 3 trials leading to regulatory approval of finasteride for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia.[1] Nonetheless, a variety of small studies have suggested a possible connection.[11][12]

Male breast cancer

In December 2009, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in the UK announced new drug safety advice on finasteride and the potential risk of male breast cancer. The agency concluded that, although overall incidence of male breast cancer in clinical trials for finasteride 5 mg was not significantly increased, a higher risk of male breast cancer with finasteride use could not be excluded.[13] Merck revised the United States' warning in consumer and medical leaflets to include the risk of male breast cancer.[3]

Mechanism of action

Finasteride is a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor, specifically the type II isoenzyme.[14] By inhibiting 5a-reductase, finasteride prevents conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by the type II isoenzyme, resulting in a decrease in serum DHT levels by about 65–70% and in prostate DHT levels by up to 85–90%,[15] where expression of the type II isoenzyme dominates. Unlike dual inhibitors of both isoenzymes of 5α-reductase which can reduce DHT levels in the entire body by more than 99%, finasteride does not completely suppress DHT production because it lacks significant inhibitory effects on the 5α-reductase type I isoenzyme, with 100-fold less affinity for I as compared to II.[3] In addition to blocking the type II isoenzyme, finasteride competitively inhibits the 5β-reductase type II isoenzyme,[16] though this is not believed to affect androgen metabolism.

By blocking DHT production, finasteride reduces androgen activity in the scalp. In the prostate, inhibition of 5α-reductase reduces prostate volume, which improves benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and reduces risk of prostate cancer. 5α-reductase inhibition also reduces epididymal weight, and decreases motility and normal morphology of spermatozoa in the epididymis.[17]

DHT helps activate the GABAA receptor, which functions to tamp down signaling among neurons; because finasteride prevents the formation of DHT, it may contribute to a reduction of GABAA activity. Reduced GABAA has been implicated in depression, anxiety, and sexual dysfunction.[12][18][19]

Physical and chemical properties

Finasteride is a 4-azasteroid analogue of testosterone and is lipophilic.[20]

Drug trade names include Propecia and Proscar, the former marketed for male pattern baldness (MPB) and the latter for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), both are products of Merck & Co. There is 1 mg of finasteride in Propecia and 5 mg in Proscar. Merck's patent on finasteride for the treatment of BPH expired on June 19, 2006.[21] Merck was awarded a separate patent for the use of finasteride to treat MPB. This patent expired in November 2013.[22]

History

In 1974, Julianne Imperato-McGinley of Cornell Medical College in New York attended a conference on birth defects. She reported on a group of intersex children in the Caribbean who appeared sexually ambiguous at birth, and were initially raised as girls, but then grew external male genitalia and other masculine characteristic post-onset of puberty. Her research group found that these children shared a genetic mutation, causing deficiency of the 5α-reductase enzyme and male hormone dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which was found to have been the etiology behind abnormalities in male sexual development. Upon maturation, these individuals were observed to have smaller prostates which were underdeveloped, and were also observed to lack incidence of male pattern baldness.[23][24]

In 1975, copies of Imperato-McGinley's presentation were seen by P. Roy Vagelos, who was then serving as Merck's basic-research chief. He was intrigued by the notion that decreased levels of DHT led to the development of smaller prostates. Dr. Vagelos then sought to create a drug which could mimic the condition found in these children in order to treat older men who were suffering from benign prostatic hyperplasia.[25]

In 1992, finasteride (5 mg) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), which Merck marketed under the brand name Proscar.

In 1997, Merck was successful in obtaining FDA approval for a second indication of finasteride (1 mg) for treatment of male pattern baldness (MPB), which was marketed under the brand name Propecia.

Society and culture

In 2005, the World Anti-Doping Agency banned finasteride because a lab in Germany discovered that the drug could be used to mask steroid abuse.[26] It was removed from the list effective January 1, 2009, after improvements in testing methods made the ban unnecessary.[27] Notable athletes who used finasteride for hair loss and were banned from international competition include skeleton racer Zach Lund, bobsledder Sebastien Gattuso, footballer Romário and ice hockey goaltender José Théodore.[27][28]

In 2012 an advocacy group called the Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation was formed; the group "coined the phrase “post finasteride syndrome” which they say is characterised by sexual, neurological, hormonal and psychological side effects that can persist in men who have taken finasteride for hair loss or an enlarged prostate."[29] [30]

Research

Finasteride has been clinically tested for baldness in women; the results were no better than placebo.[31]

See also

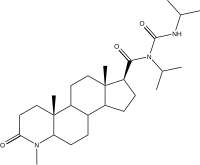

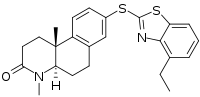

| Epristeride | 4-MA | Turosteride | Lapisteride | Izonsteride |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

- Dutasteride, related 5α-reductase inhibitor (isozyme I, II and III)

- Bexlosteride 5-α reductase inhibitor (isozyme I selective).

- Epristeride (SKF-105657) (SmithKline Beecham)

- Turosteride (FCE-26,073)

- 4-MA steroid not amp

- FCE 28260

- Izonsteride (LY-320,236)

- Lapisteride (INN; CS-891)

- Galeterone (TOK-001 or VN/124-1)

- Abiraterone

- Ganoderic acid

- Minoxidil

References

- ^ a b Tacklind, J; Fink, HA; Macdonald, R; Rutks, I; Wilt, TJ (2010 Oct 6). "Finasteride for benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (10): CD006015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006015.pub3. PMID 20927745.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Proscar label

- ^ a b c d "Propecia label" (PDF).

- ^ a b Varothai, S; Bergfeld, WF (2014 Jul). "Androgenetic alopecia: an evidence-based treatment update". American journal of clinical dermatology. 15 (3): 217–30. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0077-5. PMID 24848508.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Knezevich EL, Viereck LK, Drincic AT (January 2012). "Medical management of adult transsexual persons". Pharmacotherapy. 32 (1): 54–66. doi:10.1002/PHAR.1006. PMID 22392828.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ FDA. Posted 9 June 2011. 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs): Label Change - Increased Risk of Prostate Cancer

- ^ Walsh PC (April 2010). "Chemoprevention of prostate cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (13): 1237–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1001045. PMID 20357287.

- ^ Gupta AK, Charrette A (April 2014). "The efficacy and safety of 5α-reductase inhibitors in androgenetic alopecia: a network meta-analysis and benefit-risk assessment of finasteride and dutasteride". J Dermatolog Treat. 25 (2): 156–61. doi:10.3109/09546634.2013.813011. PMID 23768246.

- ^ Mella JM, Perret MC, Manzotti M, Catalano HN, Guyatt G (Oct 2010). "Efficacy and safety of finasteride therapy for androgenic alopecia: a systematic review". Arch Dermatol. 146 (10): 1141–50. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.256. PMID 20956649.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ FDA (11 April 2012). "Questions and Answers: Finasteride Label Changes". US FDA. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ Traish AM, Hassani J, Guay AT, Zitzmann M, Hansen ML (March 2011). "Adverse side effects of 5α-reductase inhibitors therapy: persistent diminished libido and erectile dysfunction and depression in a subset of patients". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (3): 872–84. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02157.x. PMID 21176115.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Finn DA, Beadles-Bohling AS, Beckley EH; et al. (2006). "A new look at the 5alpha-reductase inhibitor finasteride". CNS Drug Reviews. 12 (1): 53–76. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00053.x. PMID 16834758.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency Drug Safety Update. December 2009 Finasteride: potential risk of male breast cancer

- ^ Aggarwal S, Thareja S, Verma A, Bhardwaj TR, Kumar M (February 2010). "An overview on 5alpha-reductase inhibitors". Steroids. 75 (2): 109–53. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2009.10.005. PMID 19879888.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bartsch G, Rittmaster RS, Klocker H (April 2000). "Dihydrotestosterone and the concept of 5alpha-reductase inhibition in human benign prostatic hyperplasia". European Urology. 37 (4): 367–80. doi:10.1159/000020181. PMID 10765065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Drury JE, Di Costanzo L, Penning TM, Christianson DW (July 2009). "Inhibition of human steroid 5beta-reductase (AKR1D1) by finasteride and structure of the enzyme-inhibitor complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (30): 19786–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.C109.016931. PMC 2740403. PMID 19515843.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Robaire B, Henderson NA (May 2006). "Actions of 5alpha-reductase inhibitors on the epididymis". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 250 (1–2): 190–5. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.044. PMID 16476520.

- ^ Römer B, Gass P (December 2010). "Finasteride-induced depression: new insights into possible pathomechanisms". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 9 (4): 331–2. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2010.00533.x. PMID 21122055.

- ^ Gunn BG, Brown AR, Lambert JJ, Belelli D (2011). "Neurosteroids and GABA(A) Receptor Interactions: A Focus on Stress". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 5: 131. doi:10.3389/fnins.2011.00131. PMC 3230140. PMID 22164129.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Azeem A, Khan ZI, Aqil M, Ahmad FJ, Khar RK, Talegaonkar S (May 2009). "Microemulsions as a surrogate carrier for dermal drug delivery". Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy. 35 (5): 525–47. doi:10.1080/03639040802448646. PMID 19016057.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Primary Patent Expirations for Selected High Revenue Drugs

- ^ fda.gov | Patent Expiration for Propecia

- ^ Imperato-McGinley J, Guerrero L, Gautier T, Peterson RE (December 1974). "Steroid 5alpha-reductase deficiency in man: an inherited form of male pseudohermaphroditism". Science. 186 (4170): 1213–5. doi:10.1126/science.186.4170.1213. PMID 4432067.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Emerick JE et al. for WebMD. Last Updated Updated: 29 May, 2014 5-Alpha-Reductase Deficiency

- ^ Freudenheim, Milt (February 16, 1992). "Keeping the Pipeline Filled at Merck". The New York Times.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (2006-01-19). "Skin Deep; Fighting Baldness, and Now an Olympic Ban". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ a b Staff, The Australian. 28 October 2008 WADA removes Finasteride from ban list

- ^ Staff, Sydney Morning Herald. 9 October 2008 WADA takes Romario's drug off banned list

- ^ Jill Margo for the Australian Financial Review. 26 Sept 2012 Looking at care with a critical eye

- ^ Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation official website

- ^ Levy, LL; Emer, JJ (2013 Aug 29). "Female pattern alopecia: current perspectives". International journal of women's health. 5: 541–56. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S49337. PMC 3769411. PMID 24039457.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)