Fat: Difference between revisions

m →Examples: sp |

Jorge Stolfi (talk | contribs) Merged contents of saturated fat |

||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

* [[Winterization (of oil)|Winterization]] to remove oil components with higher melting points. |

* [[Winterization (of oil)|Winterization]] to remove oil components with higher melting points. |

||

* [[Clarified butter|Clarification]] of butter. |

* [[Clarified butter|Clarification]] of butter. |

||

==Saturated fat== |

|||

<!--merged-from|saturated fat--> |

|||

A '''saturated fat''' is a type of [[fat]] in which the fatty acid chains have all or predominantly [[single bond]]s. A fat is made of two kinds of smaller molecules: [[glycerol]] and [[fatty acids]]. Fats are made of long chains of carbon (C) atoms. Some carbon atoms are linked by single bonds (-C-C-) and others are linked by [[double bond]]s (-C=C-).<ref name="Campbell">{{Cite book |last1=Reece, Jane |url=https://archive.org/details/biologyc00camp/page/69 |title=Biology |last2=Campbell, Neil |publisher=Benjamin Cummings |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-8053-6624-2 |location=San Francisco |pages=[https://archive.org/details/biologyc00camp/page/69 69–70] |url-access=registration}}</ref> Double bonds can react with hydrogen to form single bonds. They are called [[Saturated and unsaturated compounds|saturated]] because the second bond is broken and each half of the bond is attached to (saturated with) a [[hydrogen]] atom. |

|||

Saturated fats tend to have higher [[melting point]]s than their corresponding unsaturated fats, leading to the popular understanding that saturated fats tend to be solids at room temperatures, while unsaturated fats tend to be liquid at room temperature with varying degrees of viscosity. |

|||

Most animal fats are saturated. The fats of plants and fish are generally unsaturated.<ref name="Campbell" /> Various foods contain different proportions of saturated and [[unsaturated fat]]. Many [[processed foods]] like foods [[deep-fried]] in [[Vegetable_oil#Hydrogenated_oils|hydrogenated oil]] and [[sausage]] are high in saturated fat content. Some store-bought [[baked goods]] are as well, especially those containing [[Trans fat|partially hydrogenated oil]]s.<ref name="aha">{{Cite web |url=http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/FatsAndOils/Fats101/Saturated-Fats_UCM_301110_Article.jsp |title=Saturated fats |date=2014 |publisher=American Heart Association |access-date=1 March 2014}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/top-food-sources-of-saturated-fat-in-the-us/ |title=Top food sources of saturated fat in the US |date=2014 |publisher=Harvard University School of Public Health |access-date=1 March 2014}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.choosemyplate.gov/node/5664 |title=Saturated, Unsaturated, and Trans Fats |date=2020 |publisher=choosemyplate.gov}}</ref> Other examples of foods containing a high proportion of saturated fat and [[dietary cholesterol]] include animal fat products such as [[lard]] or [[schmaltz]], fatty meats and [[dairy products]] made with whole or reduced fat milk like [[yogurt]], [[ice cream]], [[cheese]] and [[butter]].<ref name="aha2">{{Cite web |url=https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/fats/saturated-fats |title=Saturated Fat |date=2020 |publisher=American Heart Association}}</ref> Certain vegetable products have high saturated fat content, such as [[coconut oil]] and [[palm kernel oil]].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.choosemyplate.gov/food-groups/oils.html |title=What are "oils"? |year=2015 |publisher=ChooseMyPlate.gov, US Department of Agriculture |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150609080528/http://www.choosemyplate.gov/food-groups/oils.html |archive-date=9 June 2015 |access-date=13 June 2015}}</ref> |

|||

Guidelines released by many medical organizations, including the [[World Health Organization]], have advocated for reduction in the intake of saturated fat to promote health and reduce the risk from cardiovascular diseases. Many review articles also recommend a diet low in saturated fat and argue it will lower risks of [[cardiovascular disease]]s,<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Hooper L, Martin N, Abdelhamid A, Davey Smith G |date=June 2015 |title=Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease |journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |volume=6 |issue=6 |pages=CD011737 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD011737 |pmid=26068959}}</ref> [[diabetes]], or death.<ref name="aha2017">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JH, Appel LJ, Creager MA, Kris-Etherton PM, Miller M, Rimm EB, Rudel LL, Robinson JG, Stone NJ, Van Horn LV |date=July 2017 |title=Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association |journal=Circulation |volume=136 |issue=3 |pages=e1–e23 |doi=10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510 |pmid=28620111|s2cid=367602 }}</ref> A small number of contemporary reviews have challenged these conclusions, though predominant medical opinion is that saturated fat and cardiovascular disease are closely related.<ref name="bmj351">{{cite journal | vauthors = de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, Cozma AI, Ha V, Kishibe T, Uleryk E, Budylowski P, Schünemann H, Beyene J, Anand SS | title = Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies | journal = BMJ | volume = 351 | issue = Aug 11 | pages = h3978 | date = August 2015 | pmid = 26268692 | pmc = 4532752 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.h3978 }}</ref><ref name="bmj346">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Leelarthaepin B, Majchrzak-Hong SF, Faurot KR, Suchindran CM, Ringel A, Davis JM, Hibbeln JR | display-authors = 6 | title = Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis | journal = BMJ | volume = 346 | pages = e8707 | date = February 2013 | pmid = 23386268 | pmc = 4688426 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.e8707 }}</ref><ref name="bmj353">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Majchrzak-Hong S, Faurot KR, Broste SK, Frantz RP, Davis JM, Ringel A, Suchindran CM, Hibbeln JR | title = Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73) | journal = BMJ | volume = 353 | pages = i1246 | date = April 2016 | pmid = 27071971 | pmc = 4836695 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.i1246 }}</ref> |

|||

===Fat profiles=== |

|||

While nutrition labels regularly combine them, the saturated fatty acids appear in different proportions among food groups. [[Lauric acid|Lauric]] and [[Myristic acid|myristic]] acids are most commonly found in "tropical" oils (e.g., [[Palm kernel oil|palm kernel]], [[Coconut oil|coconut]]) and dairy products. The saturated fat in meat, [[egg (food)|eggs]], cacao, and [[nut (fruit)|nuts]] is primarily the triglycerides of [[Palmitic acid|palmitic]] and [[Stearic acid|stearic]] acids. |

|||

{|class="wikitable sortable" |

|||

|+Saturated fat profile of common foods; Esterified fatty acids as percentage of total fat<ref>{{cite web|publisher=[[United States Department of Agriculture]] |year=2007 |title=USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 20 |url=http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160414070404/http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl |archivedate=2016-04-14 }}</ref> |

|||

! width="120pt"| Food !! width="70pt"| [[Lauric acid]] !! width="70pt"| [[Myristic acid]] !! width="70pt"| [[Palmitic acid]] !! width="70pt"| [[Stearic acid]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Coconut oil]] || 47% || 18% || 9% || 3% |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Palm kernel oil]] || 48% || 1% || 44% || 5% |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Butter]] || 3% || 11% || 29% || 13% |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Ground beef]] || 0% || 4% || 26% || 15% |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Salmon]] || 0% || 1% || 29% || 3% |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Egg (food)|Egg]] yolks || 0% || 0.3% || 27% || 10% |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Cashew]]s || 2% || 1% || 10% || 7% |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Soybean oil]] || 0% || 0% || 11% || 4% |

|||

|} |

|||

===Examples of saturated fatty acids=== |

|||

{{Main|List of saturated fatty acids}} |

|||

Some common examples of fatty acids: |

|||

*[[Butyric acid]] with 4 carbon atoms (contained in [[butter]]) |

|||

*[[Lauric acid]] with 12 carbon atoms (contained in [[coconut oil]], [[palm kernel oil]], and [[breast milk]]) |

|||

*[[Myristic acid]] with 14 carbon atoms (contained in cow's [[milk]] and dairy products) |

|||

*[[Palmitic acid]] with 16 carbon atoms (contained in [[palm oil]] and [[meat]]) |

|||

*[[Stearic acid]] with 18 carbon atoms (also contained in [[meat]] and [[cocoa butter]]) |

|||

===Association with diseases=== |

|||

====Cardiovascular disease==== |

|||

{{Main|Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease}} |

|||

The effect of saturated fat on heart disease has been extensively studied.<ref name=HooperMartin2020/> There are strong, consistent, and graded relationships between saturated fat intake, [[blood cholesterol]] levels, and the epidemic of cardiovascular disease.<ref name=aha2017/> The relationships are accepted as causal.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, Cifkova R, Dallongeville J, De Backer G, Ebrahim S, Gjelsvik B, Herrmann-Lingen C, Hoes A, Humphries S, Knapton M, Perk J, Priori SG, Pyorala K, Reiner Z, Ruilope L, Sans-Menendez S, Scholte op Reimer W, Weissberg P, Wood D, Yarnell J, Zamorano JL, Walma E, Fitzgerald T, Cooney MT, Dudina A | display-authors = 6 | title = European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary | journal = European Heart Journal | volume = 28 | issue = 19 | pages = 2375–2414 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17726041 | doi = 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm316 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name=Labarthe2011>{{cite book | title = Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge | first = Darwin | last = Labarthe | name-list-format = vanc | publisher = Jones and Bartlett Publishers | year = 2011 | chapter = Chapter 17 What Causes Cardiovascular Diseases? | edition = 2nd | isbn = 978-0-7637-4689-6}}</ref> |

|||

Many health authorities such as the [[Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics]],<ref name="ADA/DOC">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kris-Etherton PM, Innis S | title = Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: Dietary Fatty Acids | journal = Journal of the American Dietetic Association | volume = 107 | issue = 9 | pages = 1599–1611 [1603] | date = September 2007 | pmid = 17936958 | doi = 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.024}}</ref> the [[British Dietetic Association]],<ref name=BDA>{{cite web|title=Food Fact Sheet - Cholesterol|url=http://www.bda.uk.com/foodfacts/cholesterol.pdf|publisher=British Dietetic Association|accessdate=3 May 2012}}</ref> [[American Heart Association]],<ref name=aha2017/> the [[World Heart Federation]],<ref name=WorldHeartFederation>{{cite web | url = http://www.world-heart-federation.org/cardiovascular-health/cardiovascular-disease-risk-factors | title = Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors|publisher=World Heart Federation|date=30 May 2017 | accessdate = 2012-05-03}}</ref> the British [[National Health Service]],<ref name = NHS>{{cite web |title=Lower your cholesterol |url=http://www.nhs.uk/livewell/healthyhearts/pages/cholesterol.aspx|publisher=[[National Health Service]] |accessdate=2012-05-03 }}</ref> among others,<ref name = FDA>{{cite web | url = https://www.fda.gov/Food/LabelingNutrition/ConsumerInformation/ucm192658.htm | title = Nutrition Facts at a Glance - Nutrients: Saturated Fat | publisher = [[Food and Drug Administration]] | date = 2009-12-22 | accessdate = 2012-05-03 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol|url=http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1461|publisher=European Food Safety Authority|accessdate=3 May 2012|date=2010-03-25}}</ref> advise that saturated fat is a [[risk factor]] for cardiovascular disease. The World Health Organization in May 2015 recommends switching from saturated to unsaturated fats.<ref>{{cite web|title=Healthy diet Fact sheet N°394|url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs394/en/|accessdate=12 August 2015|date=May 2015}}</ref> |

|||

There is moderate quality evidence that reducing the proportion of saturated fat in the diet, and replacing it with unsaturated fats or carbohydrates over a period of at least two years, leads to a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease.<ref name=HooperMartin2020>{{cite journal|vauthors=Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS |title=Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease |journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |year=2020 |volume=5 |pages=CD011737 |issn=14651858 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub2 |pmid=32428300 |pmc=7388853 |type=Systematic review}}</ref> |

|||

=====Dyslipidemia===== |

|||

{{See also|Lipid hypothesis}} |

|||

The consumption of saturated fat is generally considered a risk factor for [[dyslipidemia]], which in turn is a risk factor for some types of [[cardiovascular disease]].<ref>{{vcite web | url = http://www.fph.org.uk/uploads/ps_fat.pdf | title = Position Statement on Fat | author = Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom | accessdate=2011-01-25}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/who_fao_expert_report.pdf | title = Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases | publisher = World Health Organization | author = Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation | year = 2003 | accessdate = 2011-03-11}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = Cholesterol | url = http://www.irishheart.ie/iopen24/cholesterol-t-7_20_87.html | accessdate = 2011-02-28 | publisher = Irish Heart Foundation}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | author = U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | date = December 2010 | title = Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 | edition = 7th | location = Washington, DC | publisher = U.S. Government Printing Office | url = https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2010/dietaryguidelines2010.pdf }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | title = Critical Pathways in Cardiovascular Medicine | edition = 2nd | publisher = Lippincott Williams & Wilkins | last1 = Cannon | first1 = Christopher | last2 = O'Gara | first2 = Patrick | name-list-format = vanc | year = 2007 | page = 243}}</ref> |

|||

Abnormal blood lipid levels, that is high total cholesterol, high levels of triglycerides, high levels of [[low-density lipoprotein]] (LDL, "bad" cholesterol) or low levels of [[high-density lipoprotein]] (HDL, "good" cholesterol) cholesterol are all associated with increased risk of heart disease and stroke.<ref name=WorldHeartFederation /> |

|||

Meta-analyses have found a significant relationship between saturated fat and serum cholesterol levels.<ref name=aha2017/><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Clarke R, Frost C, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R | title = Dietary lipids and blood cholesterol: quantitative meta-analysis of metabolic ward studies | journal = BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) | volume = 314 | issue = 7074 | pages = 112–7 | year = 1997 | pmid = 9006469 | pmc = 2125600 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.314.7074.112 }}</ref> High total cholesterol levels, which may be caused by many factors, are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.<ref name=Bucher1999>{{cite journal |vauthors=Bucher HC, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH | title = Systematic review on the risk and benefit of different cholesterol-lowering interventions | journal = Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology | volume = 19 | issue = 2 | pages = 187–195 | date = February 1999 | pmid = 9974397 | doi = 10.1161/01.atv.19.2.187 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name=Lewington2007>{{cite journal |vauthors=Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R | title = Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths | journal = Lancet | volume = 370 | issue = 9602 | pages = 1829–39 | date = December 2007 | pmid = 18061058 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4 | s2cid = 54293528 | url = | issn = }}</ref> However, other indicators measuring cholesterol such as high total/HDL cholesterol ratio are more predictive than total [[serum cholesterol]].<ref name=Lewington2007/> In a study of [[myocardial infarction]] in 52 countries, the [[apolipoprotein B|ApoB]]/[[apolipoprotein A1|ApoA1]] (related to LDL and HDL, respectively) ratio was the strongest predictor of CVD among all risk factors.<ref>{{cite book | title = Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge | first = Darwin | last = Labarthe | name-list-format = vanc | publisher = Jones and Bartlett Publishers | year = 2011 | chapter = Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile | page = 290 | edition = 2 | isbn = 978-0-7637-4689-6}}</ref> There are other pathways involving [[obesity]], [[triglyceride]] levels, [[insulin resistance|insulin sensitivity]], [[endothelium|endothelial function]], and [[thrombogenicity]], among others, that play a role in CVD, although it seems, in the absence of an adverse blood lipid profile, the other known risk factors have only a weak [[atherogenic]] effect.<ref>{{cite book | title = Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge | first = Darwin | last = Labarthe | name-list-format = vanc | publisher = Jones and Bartlett Publishers | year = 2011 | chapter = Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile | page = 277 | edition = 2nd | isbn = 978-0-7637-4689-6}}</ref> Different saturated fatty acids have differing effects on various lipid levels.<ref name=Thijssen>{{cite book | vauthors = Thijssen MA, Mensink RP | chapter = Fatty acids and atherosclerotic risk | volume = 170 | issue = 170 | pages = 165–94 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16596799 | doi = 10.1007/3-540-27661-0_5 | publisher = Springer | isbn = 978-3-540-22569-0 | series = Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology | title = Atherosclerosis: Diet and Drugs }}</ref> |

|||

====Cancer==== |

|||

=====Breast cancer===== |

|||

{{Main|Epidemiology and etiology of breast cancer#Specific dietary fatty acids}} |

|||

A meta-analysis published in 2003 found a significant positive relationship in both control and cohort studies between saturated fat and breast cancer.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Boyd NF, Stone J, Vogt KN, Connelly BS, Martin LJ, Minkin S | title = Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: a meta-analysis of the published literature | journal = British Journal of Cancer | volume = 89| issue = 9 | pages = 1672–1685 | date = November 2003 | pmid = 14583769 | pmc = 2394401 | doi = 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601314 }}</ref> However two subsequent reviews have found weak or insignificant associations of saturated fat intake and breast cancer risk,<ref name=Hanf>{{cite journal |vauthors=Hanf V, Gonder U | title = Nutrition and primary prevention of breast cancer: foods, nutrients and breast cancer risk. | journal = European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology | volume = 123 | issue = 2 | pages = 139–149 | date = 2005-12-01 | pmid = 16316809 | doi = 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.05.011 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Lof M, Weiderpass E | title = Impact of diet on breast cancer risk. | journal = Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology | volume = 21 | issue = 1 | pages = 80–85 | date = February 2009 | pmid = 19125007 | doi = 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32831d7f22 | s2cid = 9513690 }}</ref> and note the prevalence of confounding factors.<ref name=Hanf/><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Freedman LS, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A, Potischman N | title = Methods of Epidemiology: Evaluating the Fat–Breast Cancer Hypothesis – Comparing Dietary Instruments and Other Developments | journal = Cancer Journal (Sudbury, Mass.) | volume = 14 | issue = 2 | pages = 69–74 | date = Mar–Apr 2008 | pmid = 18391610 | pmc = 2496993 | doi = 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31816a5e02 }}</ref> |

|||

=====Colorectal cancer===== |

|||

One review found limited evidence for a positive relationship between consuming animal fat and incidence of colorectal cancer.<ref>{{cite book|year=2009|volume=472|pages=361–72|doi=10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_16|chapter=Acquired risk factors for colorectal cancer|author=Lin OS|title = Cancer Epidemiology|pmid=19107442|series=Methods in Molecular Biology|isbn=978-1-60327-491-3}}</ref> |

|||

=====Ovarian cancer===== |

|||

Meta-analyses of clinical studies found evidence for increased risk of ovarian cancer by high consumption of saturated fat.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Huncharek M, Kupelnick B | title = Dietary fat intake and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis of 6,689 subjects from 8 observational studies | journal = Nutrition and Cancer | volume = 40 | issue = 2 | pages = 87–91 | year = 2001 | pmid = 11962260 | doi = 10.1207/S15327914NC402_2 | s2cid = 24890525 }}</ref> |

|||

=====Prostate cancer===== |

|||

{{Further|Prostate cancer#Oils and fatty acids}} |

|||

Some researchers have indicated that serum [[myristic acid]]<ref name="pmid14693732">{{cite journal |vauthors=Männistö S, Pietinen P, Virtanen MJ, Salminen I, Albanes D, Giovannucci E, Virtamo J | title = Fatty acids and risk of prostate cancer in a nested case-control study in male smokers | journal = Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention | volume = 12 | issue = 12 | pages = 1422–8 | date = December 2003 | pmid = 14693732 | url = http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14693732 }}</ref><ref name="saturated">{{cite journal |vauthors=Crowe FL, Allen NE, Appleby PN, Overvad K, Aardestrup IV, Johnsen NF, Tjønneland A, Linseisen J, Kaaks R, Boeing H, Kröger J, Trichopoulou A, Zavitsanou A, Trichopoulos D, Sacerdote C, Palli D, Tumino R, Agnoli C, Kiemeney LA, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Chirlaque MD, Ardanaz E, Larrañaga N, Quirós JR, Sánchez MJ, González CA, Stattin P, Hallmans G, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Rinaldi S, Slimani N, Jenab M, Riboli E, Key TJ | title = Fatty acid composition of plasma phospholipids and risk of prostate cancer in a case-control analysis nested within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition | journal = The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition | volume = 88 | issue = 5 | pages = 1353–63 | date = November 2008 | pmid = 18996872 | url = https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/88/5/1353/4649012| doi = 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26369 | doi-broken-date = 2020-08-23 }}</ref> and [[palmitic acid]]<ref name="saturated"/> and dietary myristic<ref name="palmiticmyristic"/> and palmitic<ref name="palmiticmyristic">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kurahashi N, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane AS | title = Dairy product, saturated fatty acid, and calcium intake and prostate cancer in a prospective cohort of Japanese men | journal = Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention | volume = 17 | issue = 4 | pages = 930–7 | date = April 2008 | pmid = 18398033 | doi = 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2681 | s2cid = 551427 }}</ref> saturated fatty acids and serum palmitic combined with [[Tocopherol#Alpha-tocopherol|alpha-tocopherol]] supplementation<ref name="pmid14693732"/> are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer in a dose-dependent manner. These associations may, however, reflect differences in intake or metabolism of these fatty acids between the precancer cases and controls, rather than being an actual cause.<ref name="saturated"/> |

|||

====Bones==== |

|||

Mounting evidence indicates that the amount and type of fat in the diet can have important effects on bone health. Most of this evidence is derived from animal studies. The data from one study indicated that bone mineral density is negatively associated with saturated fat intake, and that men may be particularly vulnerable.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Corwin RL, Hartman TJ, Maczuga SA, Graubard BI | title = Dietary saturated fat intake is inversely associated with bone density in humans: Analysis of NHANES III | journal = The Journal of Nutrition | volume = 136 | issue = 1 | pages = 159–165 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16365076 | doi = 10.1093/jn/136.1.159 | s2cid = 4443420 | url = https://semanticscholar.org/paper/d7811ba4c3926bb0830ea4ad213eae7a21fe1889 }}</ref> |

|||

===Dietary recommendations=== |

|||

Recommendations to reduce or limit dietary intake of saturated fats are made by the World Health Organization,<ref>see the article [[Food pyramid (nutrition)#Food pyramid published by the WHO and FAO|Food pyramid (nutrition)]] for more information.</ref> American Heart Association,<ref name=aha2017/> Health Canada,<ref>{{cite web | url = https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/healthy-eating-recommendations/make-it-a-habit-to-eat-vegetables-fruit-whole-grains-and-protein-foods/choosing-foods-with-healthy-fats/ | title = Choosing foods with healthy fats | publisher = [[Health Canada]] | accessdate = 2019-09-24| date = 2018-10-10 }}</ref> the US Department of Health and Human Services,<ref>{{cite web | url = https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/resources/DGA_Cut-Down-On-Saturated-Fats.pdf | title = Cut Down on Saturated Fats | publisher = [[United States Department of Health and Human Services]] | accessdate = 2019-09-24}}</ref> the UK National Health Service,<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/different-fats-nutrition/ | title = Fat: the facts | publisher = United Kingdom's [[National Health Service]] | accessdate = 2019-09-24| date = 2018-04-27 }}</ref> the Australian Department of Health and Aging,<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/food-essentials/fat-salt-sugars-and-alcohol/fat | title = Fat | publisher = Australia's [[National Health and Medical Research Council]] and [[Department of Health and Ageing]] | accessdate = 2019-09-24| date = 2012-09-24 }}</ref> the Singapore Ministry of Health,<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.healthhub.sg/live-healthy/458/Getting%20the%20Fats%20Right | title = Getting the Fats Right! | publisher = Singapore's [[Ministry of Health (Singapore)|Ministry of Health]] | accessdate = 2019-09-24}}</ref> the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Wellfare,<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.nhp.gov.in/healthlyliving/healthy-diet | title = Health Diet | publisher = India's [[Ministry of Health and Family Welfare]] | accessdate = 2019-09-24}}</ref> the New Zealand Ministry of Health,<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/eating-activity-guidelines-for-new-zealand-adults-oct15_0.pdf | title = Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults | publisher = New Zealand's [[Ministry of Health (New Zealand)|Ministry of Health]] | accessdate = 2019-09-24}}</ref> and Hong Kong's Department of Health.<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/static/100023.html | title = Know More about Fat | publisher = Hong Kong's [[Department of Health (Hong Kong)|Department of Health]] | accessdate = 2019-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) expert consultation report concluded that "intake of saturated fatty acids is directly related to cardiovascular risk.<ref name="who">{{cite book |url= http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42665/1/WHO_TRS_916.pdf |title= Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (WHO technical report series 916) |publisher= World Health Organization |author = Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation |year= 2003 |pages=81–94 |isbn= 978-92-4-120916-8 |accessdate = 2016-04-04}}</ref> The traditional target is to restrict the intake of saturated fatty acids to less than 10% of daily energy intake and less than 7% for high-risk groups. If populations are consuming less than 10%, they should not increase that level of intake. Within these limits, intake of foods rich in myristic and palmitic acids should be replaced by fats with a lower content of these particular fatty acids. In developing countries, however, where energy intake for some population groups may be inadequate, energy expenditure is high and body fat stores are low (BMI <18.5 kg/m<sup>2</sup>). The amount and quality of fat supply has to be considered keeping in mind the need to meet energy requirements. Specific sources of saturated fat, such as coconut and palm oil, provide low-cost energy and may be an important source of energy for the poor."<ref name=who/> |

|||

A 2004 statement released by the [[Centers for Disease Control]] (CDC) determined that "Americans need to continue working to reduce saturated fat intake…"<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/mmwrnews/n040206.htm#mmwr2 | title = Trends in Intake of Energy, Protein, Carbohydrate, Fat, and Saturated Fat — United States, 1971–2000 | publisher = [[Centers for Disease Control]] | year = 2004 | url-status = dead | archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20081201152506/http://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/mmwrnews/n040206.htm#mmwr2 | archivedate = 2008-12-01 }}</ref> In addition, reviews by the [[American Heart Association]] led the Association to recommend reducing saturated fat intake to less than 7% of total calories according to its 2006 recommendations.<ref>{{cite journal | author = [[Alice H. Lichtenstein|Lichtenstein AH]], Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, Franch HA, Franklin B, Kris-Etherton P, Harris WS, Howard B, Karanja N, Lefevre M, Rudel L, Sacks F, Van Horn L, Winston M, Wylie-Rosett J | title = Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee | journal = Circulation | volume = 114 | issue = 1 | pages = 82–96 | date = July 2006 | pmid = 16785338 | doi = 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158 | s2cid = 647269 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Smith SC, Jackson R, Pearson TA, Fuster V, Yusuf S, Faergeman O, Wood DA, Alderman M, Horgan J, Home P, Hunn M, Grundy SM | title = Principles for national and regional guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the World Heart and Stroke Forum | journal = Circulation | volume = 109 | issue = 25 | pages = 3112–21 | date = June 2004 | pmid = 15226228 | doi = 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133427.35111.67 | url = http://www.sisalombardia.it/pdfs/guideline_world_heart_and_stroke_forum.pdf }}</ref> This concurs with similar conclusions made by the US [[Department of Health and Human Services]], which determined that reduction in saturated fat consumption would positively affect health and reduce the prevalence of heart disease.<ref name=DGfA>{{cite web | publisher = [[United States Department of Agriculture]] | url = https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dockets/06q0458/06q-0458-sup0001-02.pdf | title = Dietary Guidelines for Americans | year = 2005}}</ref> |

|||

The [[United Kingdom]], [[National Health Service]] claims the majority of British people eat too much saturated fat. The [[British Heart Foundation]] also advises people to cut down on saturated fat. People are advised to cut down on saturated fat and read labels on food they buy.<ref>[http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/Goodfood/Pages/Eat-less-saturated-fat.aspx Eat less saturated fat]</ref><ref>[https://www.bhf.org.uk/heart-health/preventing-heart-disease/healthy-eating/fats-explained Fats explained]</ref> |

|||

A 2004 review stated that "no lower safe limit of specific saturated fatty acid intakes has been identified" and recommended that the influence of varying saturated fatty acid intakes against a background of different individual lifestyles and genetic backgrounds should be the focus in future studies.<ref name=German>{{cite journal |vauthors=German JB, Dillard CJ | title = Saturated fats: what dietary intake? | journal = American Journal of Clinical Nutrition | volume = 80 | issue = 3 | pages = 550–559 | date = September 2004 | pmid = 15321792 | doi = 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.550 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

Blanket recommendations to lower saturated fat were criticized at a 2010 conference debate of the [[American Dietetic Association]] for focusing too narrowly on reducing saturated fats rather than emphasizing increased consumption of healthy fats and unrefined carbohydrates. Concern was expressed over the health risks of replacing saturated fats in the diet with refined carbohydrates, which carry a high risk of obesity and heart disease, particularly at the expense of [[polyunsaturated fat]]s which may have health benefits. None of the panelists recommended heavy consumption of saturated fats, emphasizing instead the importance of overall dietary quality to cardiovascular health.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Zelman K | title = The Great Fat Debate: A Closer Look at the Controversy—Questioning the Validity of Age-Old Dietary Guidance | journal = Journal of the American Dietetic Association | volume = 111 | issue = 5 | pages = 655–658 | year = 2011 | pmid = 21515106 | pmc = | doi = 10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.026 }}</ref> |

|||

In a 2017 comprehensive review of the literature and clinical trials, the American Heart Association published a recommendation that saturated fat intake be reduced or replaced by products containing monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, a dietary adjustment that could reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases by 30%.<ref name=aha2017/> |

|||

===Molecular description=== |

|||

[[File:Myristic acid.svg|thumb|left|500px|Two-dimensional representation of the saturated fatty acid [[myristic acid]]]] |

|||

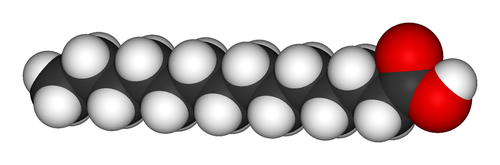

[[File:Myristic-acid-3D-vdW.png|thumb|left|500px|A [[space-filling model]] of the saturated fatty acid [[myristic acid]]]] The two-dimensional illustration has implicit hydrogen atoms bonded to each of the carbon atoms in the polycarbon tail of the [[myristic acid]] molecule (there are 13 carbon atoms in the tail; 14 carbon atoms in the entire molecule). |

|||

Carbon atoms are also implicitly drawn, as they are portrayed as [[Line-line intersection|intersections]] between two straight lines. "Saturated," in general, refers to a maximum number of hydrogen atoms bonded to each carbon of the polycarbon tail as allowed by the [[Octet Rule]]. This also means that only [[single bond]]s ([[sigma bonds]]) will be present between adjacent carbon atoms of the tail. |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

==Nutritional and health aspects== |

==Nutritional and health aspects== |

||

| Line 163: | Line 265: | ||

* [[Vegetable oil]] |

* [[Vegetable oil]] |

||

* [[Yellow grease]] |

* [[Yellow grease]] |

||

<!--Merged from [[saturated fat]]--> |

|||

*[[List of saturated fatty acids]] |

|||

*[[List of vegetable oils]] |

|||

*[[Trans fat]] |

|||

*[[Food groups]] |

|||

*[[Food guide pyramid]] |

|||

*[[Healthy diet]] |

|||

*[[Diet and heart disease]] |

|||

*[[Fast food]] |

|||

*[[Junk food]] |

|||

*[[Advanced glycation endproduct]] |

|||

*[[ANGPTL4]] |

|||

*[[Iodine value]] |

|||

*[[Framingham Heart Study]] |

|||

*[[Seven Countries Study]] |

|||

*[[Ancel Keys]] |

|||

*[[D. Mark Hegsted]] |

|||

*[[Western pattern diet]] |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

<!--merged from [[saturated fat]]--> |

|||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | vauthors = Feinman RD | title = Saturated fat and health: recent advances in research | journal = Lipids | volume = 45 | issue = 10 | pages = 891–2 | date = October 2010 | pmid = 20827513 | pmc = 2974200 | doi = 10.1007/s11745-010-3446-8 }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |vauthors=Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kuller LH, LaCroix AZ, Langer RD, Lasser NL, Lewis CE, Limacher MC, Margolis KL, Mysiw WJ, Ockene JK, Parker LM, Perri MG, Phillips L, [[Ross Prentice|Prentice RL]], Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto GE, Schatz IJ, Snetselaar LG, Stevens VJ, Tinker LF, Trevisan M, Vitolins MZ, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black HR, Brunner RL, Brzyski RG, Caan B, Chlebowski RT, Gass M, Granek I, Greenland P, Hays J, Heber D, Heiss G, Hendrix SL, Hubbell FA, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM | display-authors = 6 | title = Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial | journal = Journal of the American Medical Association | volume = 295 | issue = 6 | pages = 655–66 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16467234 | doi = 10.1001/jama.295.6.655 | doi-access = free }} |

|||

* {{cite journal | vauthors = Zelman K | title = The great fat debate: a closer look at the controversy-questioning the validity of age-old dietary guidance | journal = Journal of the American Dietetic Association | volume = 111 | issue = 5 | pages = 655–8 | date = May 2011 | pmid = 21515106 | doi = 10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.026 }} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 14:30, 30 August 2020

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| Components |

| Manufactured fats |

In nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such compounds; most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.[1]

The term often refers specifically to triglycerides (triple esters of glycerol), that are the main components of vegetable oils and of fatty tissue in animals and humans;[2] or, even more narrowly, to triglycerides that are solid or semisolid at room temperature, thus excluding oils. The term may also be used more broadly as a synonym of lipid -- any substance of biological relevance, composed of carbon, hydrogen, or oxygen, that is insoluble in water but soluble in non-polar solvents.[1] In this sense, besides the triglycerides, the term would include several other types of compounds like mono- and diglycerides, phospholipids (such as lecithin), sterols (such as cholesterol), waxes (such as beeswax),[1] and free fatty acids, which are usually present in human diet in smaller amounts.[2]

Fats are one of the three main macronutrient groups in human diet, along with carbohydrates and proteins,[1][3] and the main components of common food products like milk, butter, tallow, lard, bacon, and cooking oils. They are a major and dense source of food energy for many animals and play important structural and metabolic functions, in most living beings, including energy storage, waterproofing, and thermal insulation.[4] The human body can produce the fat that it needs from other food ingredients, except for a few essential fatty acids that must be included in the diet. Dietary fats are also the carriers of some flavor and aroma ingredients and vitamins that are not water-soluble.[2]

Chemical structure

The most important elements in the chemical makeup of fats are the fatty acids. The molecule of a fatty acid consists of a carboxyl group HO(O=)C– connected to an unbranched alkyl group –(CH

x)

nH: namely, a chain of carbon atoms, joined by single, double, or (more rarely) triple bonds, with all remaining free bonds filled by hydrogen atoms[5]

The most common type of fat, in human diet and most living beings, is a triglyceride, an ester of the triple alcohol glycerol H(–CHOH–)

3H and three fatty acids. The molecule of a trigliceride can be described as resulting from a condensation reaction (specifically, esterification) between each of glycerol's –OH groups and the HO– part of the carboxyl group HO(O=)C– of each fatty acid, forming an ester bridge –O–(O=)C– with elimination of a water molecule H

2O.

Other less common types of fats include diglycerides and monoglycerides, where the esterification is limited to two or just one of glycerol's –OH groups. Other alcohols, such as cetyl alcohol (predominant in spermaceti), may replace glycerol. In the phospholipids, one of the fatty acids is replaced by phosphoric acid or a monoester thereof.

Conformation

The shape of fat and fatty acid molecules is usually not well-defined. Any two parts of a molecule that are connected by just one single bond are free to rotate about that bond. Thus a fatty acid molecule with n simple bonds can be deformed in n-1 independent ways (counting also rotation of the terminal methyl group).

Such rotation cannot happen across a double bond, except by breaking and then reforming it with one of the halves of the molecule rotated by 180 degrees, which requires crossing a significant energy barrier. Thus a fat or fatty acid molecule with double bonds (excluding at the very end of the chain) can have multiple cis-trans isomers with significantly different chemical and biological properties. Each double bond reduces the number of conformational degrees of freedom by one. Each triple bond forces the four nearest carbons to lie in a straight line, removing two degrees of freedom.

It follows that depictions of "saturated" fatty acids with no double bonds (like stearic) having a "straight zig-zag" shape, and those with one cis bond (like oleic) being bent in an "elbow" shape are somewhat misleading. While the latter are a little less flexible, both can be twisted to assume similar straight or elbow shapes. In fact, outside of some specific contxts like crystals or bilayer membranes, both are more likely to be found in randomly contorted configurations than in either of those two shapes.

Examples

| Stearic acid saturated |

|

|---|---|

| Oleic acid unsaturated cis-8) |

|

| Elaidic acid unsaturated trans-8) |

|

| Vaccenic acid unsaturated trans-11) |

|

Stearic acid is a saturated fatty acid (with only single bonds) found in animal fats, and is the intended product in full hydrogenation.

Oleic acid has a double bond (thus being "unsaturated") with cis geometry about midway in the chain; it makes up 55–80% of olive oil.

Elaidic acid is its trans isomer; it may be present in partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, and also occurs in the fat of the durian fruit (about 2%) and in milk fat (less than 0.1%).

Vaccenic acid is another trans acid that differs from elaidic only in the position of the double bond; it also occurs in milk fat (about 1-2%).

Nomenclature

Common fat names

Fats are usually named after their source (like butterfat, olive oil, cod liver oil, tail fat) or have traditional names of their own (like butter, lard, ghee, and margarine). Some of these names refer to products that contain substantial amounts of other components besides fats proper.

Chemical fatty acid names

In chemistry and biochemistry, dozens of saturated fatty acids and of hundreds of unsaturated ones have proper scientfic/technical names usually inspired by their source fats (butyric, caprylic, stearic, oleic, palmitic, and nervonic), but sometimes their discoverer (mead, osbond).

A triglyceride would then be named as an ester of those acids, such as "glyceryl 1,2-dioleate 3-palmitate".[6]

IUPAC

In the general chemical nomenclature developed by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), the recommended name of a fatty acid, derived from the name of the corresponding hydrocarbon, completely describes its structure, by specifying the number of carbons and the number and position of the double bonds. Thus, for example, oleic acid would be called "(9Z)-octadec-9-enoic acid", meaning that it has a 18 carbon chain ("octadec") with a carboxyl at one end ("oic") and a double bound at carbon 9 counting from the carboxyl ("9-en"), and that the configuration of the single bonds adjacent to that double bond is cis ("(9Z)") The IUPAC nomenclature can also handle branched chains and derivatives where hydrogen atoms are replaced by other chemical groups.

A triglyceride would then be named according to general ester rules as, for example, "propane-1,2,3-tryl 1,2-bis((9Z)-octadec-9-enoate) 3-(hexadecanoate)".

Fatty acid code

A notation specific for fatty acids with unbranched chain, that is as precise as the IUPAC one but easier to parse, is a code of the form "{N}:{D} cis-{CCC} trans-{TTT}", where {N} is the number of carbons (including the carboxyl one), {D} is the number of double bonds, {CCC} is a list of the positions of the cis double bonds, and {TTT} is a list of the postions of the trans bounds. Either list and the label is omitted if there are no bounds of that type.

Thus, for example, the codes for stearic, oleic, elaidic, and vaccenic acids would be "18:0", "18:1 cis-9", "18:1 trans-9", and "18:1 trans-11", respectively. The code for α-oleostearic acid, which is "(9E,11E,13Z)-octadeca-9,11,13-trienoic acid" in the IUPAC nomenclature, has the code "18:3 trans-9,11 cis-13"

Classification

By chain length

Fats can be classified according to the lengths of the carbon chains of their constituent fatty acids. Most chemical properties, such as melting point and acidity, vary gradually with this parameter, so there is no sharp division. Chemically, formic acid (1 carbon) and acetic acid (2 carbons) could be viewed as the shortest fatty acids; then triformin would be the simplest trigliceride. However, the terms "fatty acid" and "fat" are usually reserved for compounds with substantially longer chains.[citation needed]

A division commonly made in biochemistry and nutrition is:[citation needed]

- Short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) with less than six carbons (e. g. butyric acid).

- Medium-chain fatty acid (MCFA) with 6 to 12 carbons (e.g. capric acid).

- Long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) with 13 to 21 carbons (e.g. petroselinic acid).

- Very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) with 22 or more carbons (e. g. cerotic acid with 26)

A triglyceride molecule may have fatty acid elements of different lengths, and a fat product will often be a mix of various triglycerides. Most fats found in food, whether vegetable or animal, are made up of medium to long-chain fatty acids, usually of equal or nearly equal length.

Saturated and unsaturated fats

For human nutrition, an important classification of fats is based on the number and position of double bonds in the constituent fatty acids. Saturated fat has a predominance of saturated fatty acids, without any double bonds, while unsaturated fat has predominantly unsaturated acids with double bonds.

Unsaturated fatty acids are further classified into "monounsaturated", with a single double bond, and "polyunsaturated" with two or more. Natural fats usually contain several different saturated and unsaturated acids, even on the same molecule. For example, in most vegetable oils, the saturated palmitic (C16:0) and stearic (C18:0) acid residues are usually attached to positions 1 and 3 (sn1 and sn3) of the glycerol hub, whereas the middle position (sn2) is usually occupied by an unsaturated one, such as oleic (C18:1, ω–9) or linoleic (C18:2, ω–6).[7])

Saturated fats generally have a higher melting point than usaturated ones with the same molecular weight, and thus are more likely to be solid at room temperature. For example, the animal fats tallow and lard are high in saturated fatty acid content and are solids. Olive and linseed oils on the other hand are unsaturated and liquid. Unsaturated fats are prone to oxidation by air, which causes them to become rancid and inedible.

The double bonds in unsaturated fats can be converted into single bonds by reaction with hydrogen effected by a catalyst. This process, called hydrogenation, is used to turn vegetable vegetable oils into solid or semisolid vegetable fats like margarine, which can substitute for tallow and butter and (unlike unsaturated fats) can be stored indefinitely without becoming rancid. However, partial hydrogenation also creates some unwanted trans acids from cis acids.[citation needed]

Cis and trans fats

Another important classification of unsaturated fatty acids considers the cis-trans isomerism, the spatial arrangement of the single bonds adjacent to the double bonds. Most unsaturated fatty acids that occur in nature have those bonds in the cis ("same side") configuration.

Omega number

Another classification considers the position of double bonds, counted from the "ω" (omega) or "n" carbon atom at the end opposite to the carboxyl group. Thus, for example, alpha-linolenic acid is an omega-3 fatty acid because the 3rd carbon from that end is the first to have a double bond.

Biological importance

In humans and many animals, fats serve both as energy sources and as stores for energy in excess of what the body needs immediately. Each gram of fat when burned or metabolized releases about 9 food calories (37 kJ = 8.8 kcal).[8]

Fats are also sources of essential fatty acids, an important dietary requirement. Vitamins A, D, E, and K are fat-soluble, meaning they can only be digested, absorbed, and transported in conjunction with fats.

Fats play a vital role in maintaining healthy skin and hair, insulating body organs against shock, maintaining body temperature, and promoting healthy cell function. Fat also serves as a useful buffer against a host of diseases. When a particular substance, whether chemical or biotic, reaches unsafe levels in the bloodstream, the body can effectively dilute—or at least maintain equilibrium of—the offending substances by storing it in new fat tissue.[citation needed] This helps to protect vital organs, until such time as the offending substances can be metabolized or removed from the body by such means as excretion, urination, accidental or intentional bloodletting, sebum excretion, and hair growth.

Adipose tissue

In animals, adipose tissue, or fatty tissue is the body's means of storing metabolic energy over extended periods of time. Adipocytes (fat cells) store fat derived from the diet and from liver metabolism. Under energy stress these cells may degrade their stored fat to supply fatty acids and also glycerol to the circulation. These metabolic activities are regulated by several hormones (e.g., insulin, glucagon and epinephrine). Adipose tissue also secretes the hormone leptin.[9]

The location of the tissue determines its metabolic profile: visceral fat is located within the abdominal wall (i.e., beneath the wall of abdominal muscle) whereas subcutaneous fat is located beneath the skin (and includes fat that is located in the abdominal area beneath the skin but above the abdominal muscle wall). Visceral fat was recently discovered to be a significant producer of signaling chemicals (i.e., hormones), among which several are involved in inflammatory tissue responses. One of these is resistin which has been linked to obesity, insulin resistance, and Type 2 diabetes. This latter result is currently controversial, and there have been reputable studies supporting all sides on the issue.[citation needed]

Production and processing

A variety of chemical and physical techniques are used for the production and processing of fats, both industrially and in cottage or home settings. They include:

- Pressing to extract liquid fats from fruits, seeds, or algae, e.g. olive oil from olives;

- Solvent extraction using solvents like hexane or supercritical carbon dioxide.

- Rendering, the melting of fat in adipose tissue, e.g. to produce tallow, lard, fish oil, and whale oil.

- Churning of milk to produce butter.

- Hydrogenation to reduce the degree of unsaturation of the fatty acids.

- Interesterification, the rearrangement of fatty acids across different triglicerides.

- Winterization to remove oil components with higher melting points.

- Clarification of butter.

Saturated fat

A saturated fat is a type of fat in which the fatty acid chains have all or predominantly single bonds. A fat is made of two kinds of smaller molecules: glycerol and fatty acids. Fats are made of long chains of carbon (C) atoms. Some carbon atoms are linked by single bonds (-C-C-) and others are linked by double bonds (-C=C-).[10] Double bonds can react with hydrogen to form single bonds. They are called saturated because the second bond is broken and each half of the bond is attached to (saturated with) a hydrogen atom.

Saturated fats tend to have higher melting points than their corresponding unsaturated fats, leading to the popular understanding that saturated fats tend to be solids at room temperatures, while unsaturated fats tend to be liquid at room temperature with varying degrees of viscosity.

Most animal fats are saturated. The fats of plants and fish are generally unsaturated.[10] Various foods contain different proportions of saturated and unsaturated fat. Many processed foods like foods deep-fried in hydrogenated oil and sausage are high in saturated fat content. Some store-bought baked goods are as well, especially those containing partially hydrogenated oils.[11][12][13] Other examples of foods containing a high proportion of saturated fat and dietary cholesterol include animal fat products such as lard or schmaltz, fatty meats and dairy products made with whole or reduced fat milk like yogurt, ice cream, cheese and butter.[14] Certain vegetable products have high saturated fat content, such as coconut oil and palm kernel oil.[15]

Guidelines released by many medical organizations, including the World Health Organization, have advocated for reduction in the intake of saturated fat to promote health and reduce the risk from cardiovascular diseases. Many review articles also recommend a diet low in saturated fat and argue it will lower risks of cardiovascular diseases,[16] diabetes, or death.[17] A small number of contemporary reviews have challenged these conclusions, though predominant medical opinion is that saturated fat and cardiovascular disease are closely related.[18][19][20]

Fat profiles

While nutrition labels regularly combine them, the saturated fatty acids appear in different proportions among food groups. Lauric and myristic acids are most commonly found in "tropical" oils (e.g., palm kernel, coconut) and dairy products. The saturated fat in meat, eggs, cacao, and nuts is primarily the triglycerides of palmitic and stearic acids.

| Food | Lauric acid | Myristic acid | Palmitic acid | Stearic acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut oil | 47% | 18% | 9% | 3% |

| Palm kernel oil | 48% | 1% | 44% | 5% |

| Butter | 3% | 11% | 29% | 13% |

| Ground beef | 0% | 4% | 26% | 15% |

| Salmon | 0% | 1% | 29% | 3% |

| Egg yolks | 0% | 0.3% | 27% | 10% |

| Cashews | 2% | 1% | 10% | 7% |

| Soybean oil | 0% | 0% | 11% | 4% |

Examples of saturated fatty acids

Some common examples of fatty acids:

- Butyric acid with 4 carbon atoms (contained in butter)

- Lauric acid with 12 carbon atoms (contained in coconut oil, palm kernel oil, and breast milk)

- Myristic acid with 14 carbon atoms (contained in cow's milk and dairy products)

- Palmitic acid with 16 carbon atoms (contained in palm oil and meat)

- Stearic acid with 18 carbon atoms (also contained in meat and cocoa butter)

Association with diseases

Cardiovascular disease

The effect of saturated fat on heart disease has been extensively studied.[22] There are strong, consistent, and graded relationships between saturated fat intake, blood cholesterol levels, and the epidemic of cardiovascular disease.[17] The relationships are accepted as causal.[23][24]

Many health authorities such as the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics,[25] the British Dietetic Association,[26] American Heart Association,[17] the World Heart Federation,[27] the British National Health Service,[28] among others,[29][30] advise that saturated fat is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The World Health Organization in May 2015 recommends switching from saturated to unsaturated fats.[31]

There is moderate quality evidence that reducing the proportion of saturated fat in the diet, and replacing it with unsaturated fats or carbohydrates over a period of at least two years, leads to a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease.[22]

Dyslipidemia

The consumption of saturated fat is generally considered a risk factor for dyslipidemia, which in turn is a risk factor for some types of cardiovascular disease.[32][33][34][35][36]

Abnormal blood lipid levels, that is high total cholesterol, high levels of triglycerides, high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL, "bad" cholesterol) or low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL, "good" cholesterol) cholesterol are all associated with increased risk of heart disease and stroke.[27]

Meta-analyses have found a significant relationship between saturated fat and serum cholesterol levels.[17][37] High total cholesterol levels, which may be caused by many factors, are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[38][39] However, other indicators measuring cholesterol such as high total/HDL cholesterol ratio are more predictive than total serum cholesterol.[39] In a study of myocardial infarction in 52 countries, the ApoB/ApoA1 (related to LDL and HDL, respectively) ratio was the strongest predictor of CVD among all risk factors.[40] There are other pathways involving obesity, triglyceride levels, insulin sensitivity, endothelial function, and thrombogenicity, among others, that play a role in CVD, although it seems, in the absence of an adverse blood lipid profile, the other known risk factors have only a weak atherogenic effect.[41] Different saturated fatty acids have differing effects on various lipid levels.[42]

Cancer

Breast cancer

A meta-analysis published in 2003 found a significant positive relationship in both control and cohort studies between saturated fat and breast cancer.[43] However two subsequent reviews have found weak or insignificant associations of saturated fat intake and breast cancer risk,[44][45] and note the prevalence of confounding factors.[44][46]

Colorectal cancer

One review found limited evidence for a positive relationship between consuming animal fat and incidence of colorectal cancer.[47]

Ovarian cancer

Meta-analyses of clinical studies found evidence for increased risk of ovarian cancer by high consumption of saturated fat.[48]

Prostate cancer

Some researchers have indicated that serum myristic acid[49][50] and palmitic acid[50] and dietary myristic[51] and palmitic[51] saturated fatty acids and serum palmitic combined with alpha-tocopherol supplementation[49] are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer in a dose-dependent manner. These associations may, however, reflect differences in intake or metabolism of these fatty acids between the precancer cases and controls, rather than being an actual cause.[50]

Bones

Mounting evidence indicates that the amount and type of fat in the diet can have important effects on bone health. Most of this evidence is derived from animal studies. The data from one study indicated that bone mineral density is negatively associated with saturated fat intake, and that men may be particularly vulnerable.[52]

Dietary recommendations

Recommendations to reduce or limit dietary intake of saturated fats are made by the World Health Organization,[53] American Heart Association,[17] Health Canada,[54] the US Department of Health and Human Services,[55] the UK National Health Service,[56] the Australian Department of Health and Aging,[57] the Singapore Ministry of Health,[58] the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Wellfare,[59] the New Zealand Ministry of Health,[60] and Hong Kong's Department of Health.[61]

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) expert consultation report concluded that "intake of saturated fatty acids is directly related to cardiovascular risk.[62] The traditional target is to restrict the intake of saturated fatty acids to less than 10% of daily energy intake and less than 7% for high-risk groups. If populations are consuming less than 10%, they should not increase that level of intake. Within these limits, intake of foods rich in myristic and palmitic acids should be replaced by fats with a lower content of these particular fatty acids. In developing countries, however, where energy intake for some population groups may be inadequate, energy expenditure is high and body fat stores are low (BMI <18.5 kg/m2). The amount and quality of fat supply has to be considered keeping in mind the need to meet energy requirements. Specific sources of saturated fat, such as coconut and palm oil, provide low-cost energy and may be an important source of energy for the poor."[62]

A 2004 statement released by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) determined that "Americans need to continue working to reduce saturated fat intake…"[63] In addition, reviews by the American Heart Association led the Association to recommend reducing saturated fat intake to less than 7% of total calories according to its 2006 recommendations.[64][65] This concurs with similar conclusions made by the US Department of Health and Human Services, which determined that reduction in saturated fat consumption would positively affect health and reduce the prevalence of heart disease.[66]

The United Kingdom, National Health Service claims the majority of British people eat too much saturated fat. The British Heart Foundation also advises people to cut down on saturated fat. People are advised to cut down on saturated fat and read labels on food they buy.[67][68]

A 2004 review stated that "no lower safe limit of specific saturated fatty acid intakes has been identified" and recommended that the influence of varying saturated fatty acid intakes against a background of different individual lifestyles and genetic backgrounds should be the focus in future studies.[69]

Blanket recommendations to lower saturated fat were criticized at a 2010 conference debate of the American Dietetic Association for focusing too narrowly on reducing saturated fats rather than emphasizing increased consumption of healthy fats and unrefined carbohydrates. Concern was expressed over the health risks of replacing saturated fats in the diet with refined carbohydrates, which carry a high risk of obesity and heart disease, particularly at the expense of polyunsaturated fats which may have health benefits. None of the panelists recommended heavy consumption of saturated fats, emphasizing instead the importance of overall dietary quality to cardiovascular health.[70]

In a 2017 comprehensive review of the literature and clinical trials, the American Heart Association published a recommendation that saturated fat intake be reduced or replaced by products containing monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, a dietary adjustment that could reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases by 30%.[17]

Molecular description

The two-dimensional illustration has implicit hydrogen atoms bonded to each of the carbon atoms in the polycarbon tail of the myristic acid molecule (there are 13 carbon atoms in the tail; 14 carbon atoms in the entire molecule).

Carbon atoms are also implicitly drawn, as they are portrayed as intersections between two straight lines. "Saturated," in general, refers to a maximum number of hydrogen atoms bonded to each carbon of the polycarbon tail as allowed by the Octet Rule. This also means that only single bonds (sigma bonds) will be present between adjacent carbon atoms of the tail.

Nutritional and health aspects

The benefits and risks of dietary fats have been the object of much study, and are still highly controversial topics.[71][72][73][74]

Essential fatty acids

There are two essential fatty acids (EFAs) in human nutrition: alpha-linolenic acid (an omega-3 fatty acid) and linoleic acid (an omega-6 fatty acid).[75][8] Other lipids needed by the body can be synthesized from these and other fats.

Saturated vs. unsaturated fats

Studies have found that replacing saturated fats with cis unsaturated fats in the diet reduces risk of cardiovascular disease. For example, a 2020 systematic review of randomized control trials by the Cochrane Library concluded: "Lifestyle advice to all those at risk of cardiovascular disease and to lower risk population groups should continue to include permanent reduction of dietary saturated fat and partial replacement by unsaturated fats."[76]

Cis vs. trans fats

Numerous studies have also found that consumption of trans fats increases risk of cardiovascular disease.[75][8] The Harvard School of Public Health advises that replacing trans fats and saturated fats with cis monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats is beneficial for health.[77]

Interesterification

Some studies have investigated the health effects of insteresterified (IE) fats, by comparing diets with IE and non-IE fats with the same overall fatty acid composition.[78]

Several experimental studies in humans found no statistical difference on fasting blood lipids between a with large amounts of IE fat, having 25-40% C16:0 or C18:0 on the 2-position, and a similar diet with non-IE fat, having only 3-9% C16:0 or C18:0 on the 2-position.[79][80][81] A negative result was obtained also in a study that compared the effects on blood cholesterol levels of an IE fat product mimicking cocoa butter and the real non-IE product.[82][83][84][85][86][87][88]

A 2007 study funded by the Malaysian Palm Oil Board[89] claimed that replacing natural palm oil by other interesterified or partial hydrogenated fats caused adverse health effects, such as higher LDL/HDL ratio and plasma glucose levels. However, these effects could be attributed to the higher percentage of saturated acids in the IE and partially hydrogenated fats, rather than to the IE process itself.[90][91]

Fat digestion and metabolism

Fats are broken down in the healthy body to release their constituents, glycerol and fatty acids. Glycerol itself can be converted to glucose by the liver and so become a source of energy. Fats and other lipids are broken down in the body by enzymes called lipases produced in the pancreas.

Many cell types can use either glucose or fatty acids as a source of energy for metabolism. In particular, heart and skeletal muscle prefer fatty acids.[citation needed] Despite long-standing assertions to the contrary, fatty acids can also be used as a source of fuel for brain cells through mitochondrial oxidation. [92]

See also

- Animal fat

- Carbohydrate

- Dieting

- Fat content of milk

- Food composition data

- Lipid

- Omega-3 fatty acid

- Omega-6 fatty acid

- Trans fat

- Vegetable oil

- Yellow grease

- List of saturated fatty acids

- List of vegetable oils

- Trans fat

- Food groups

- Food guide pyramid

- Healthy diet

- Diet and heart disease

- Fast food

- Junk food

- Advanced glycation endproduct

- ANGPTL4

- Iodine value

- Framingham Heart Study

- Seven Countries Study

- Ancel Keys

- D. Mark Hegsted

- Western pattern diet

Further reading

- Feinman RD (October 2010). "Saturated fat and health: recent advances in research". Lipids. 45 (10): 891–2. doi:10.1007/s11745-010-3446-8. PMC 2974200. PMID 20827513.

- Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. (2006). "Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial". Journal of the American Medical Association. 295 (6): 655–66. doi:10.1001/jama.295.6.655. PMID 16467234.

- Zelman K (May 2011). "The great fat debate: a closer look at the controversy-questioning the validity of age-old dietary guidance". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 111 (5): 655–8. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.026. PMID 21515106.

References

- ^ a b c d Entry for "fat" in the online Merriam-Webster disctionary, sense 3.2. Accessed on 2020-08-09

- ^ a b c Thomas A. B. Sanders (2016): "The Role of Fats in Human Diet". Pages 1-20 of Functional Dietary Lipids. Woodhead/Elsevier, 332 pages. ISBN 978-1-78242-247-1doi:10.1016/B978-1-78242-247-1.00001-6

- ^ "Macronutrients: the Importance of Carbohydrate, Protein, and Fat". McKinley Health Center. University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "Introduction to Energy Storage". Khan Academy.

- ^ Anna Ohtera, Yusaku Miyamae, Naomi Nakai, Atsushi Kawachi, Kiyokazu Kawada, Junkyu Han, Hiroko Isoda, Mohamed Neffati, Toru Akita, Kazuhiro Maejima, Seiji Masuda, Taiho Kambe, Naoki Mori, Kazuhiro Irie, and Masaya Nagao (2013): "Identification of 6-octadecynoic acid from a methanol extract of Marrubium vulgare L. as a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonist". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, volume 440, issue 2, pages 204-209. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.003

- ^ N. Koeniger and H. J. Veith (1983): "Glyceryl-1,2-dioleate-3-palmitate, a brood pheromone of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.)". Experientia, volume 39, pages 1051–1052 doi:10.1007/BF01989801

- ^ Institute of Shortenings and Edible oils (2006). "Food Fats and oils" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-26. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- ^ a b c Government of the United Kingdom (1996): "Schedule 7: Nutrition labelling". In Food Labelling Regulations 1996'. Accessed on 2020-08-09.

- ^ "The human proteome in adipose - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- ^ a b Reece, Jane; Campbell, Neil (2002). Biology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-8053-6624-2.

- ^ "Saturated fats". American Heart Association. 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Top food sources of saturated fat in the US". Harvard University School of Public Health. 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Saturated, Unsaturated, and Trans Fats". choosemyplate.gov. 2020.

- ^ "Saturated Fat". American Heart Association. 2020.

- ^ "What are "oils"?". ChooseMyPlate.gov, US Department of Agriculture. 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Hooper L, Martin N, Abdelhamid A, Davey Smith G (June 2015). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737. PMID 26068959.

- ^ a b c d e f Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JH, Appel LJ, Creager MA, Kris-Etherton PM, Miller M, Rimm EB, Rudel LL, Robinson JG, Stone NJ, Van Horn LV (July 2017). "Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 136 (3): e1–e23. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510. PMID 28620111. S2CID 367602.

- ^ de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, Cozma AI, Ha V, Kishibe T, Uleryk E, Budylowski P, Schünemann H, Beyene J, Anand SS (August 2015). "Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". BMJ. 351 (Aug 11): h3978. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3978. PMC 4532752. PMID 26268692.

- ^ Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Leelarthaepin B, Majchrzak-Hong SF, Faurot KR, Suchindran CM, et al. (February 2013). "Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis". BMJ. 346: e8707. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8707. PMC 4688426. PMID 23386268.

- ^ Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Majchrzak-Hong S, Faurot KR, Broste SK, Frantz RP, Davis JM, Ringel A, Suchindran CM, Hibbeln JR (April 2016). "Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73)". BMJ. 353: i1246. doi:10.1136/bmj.i1246. PMC 4836695. PMID 27071971.

- ^ "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 20". United States Department of Agriculture. 2007. Archived from the original on 2016-04-14.

- ^ a b Hooper L, Martin N, Jimoh OF, Kirk C, Foster E, Abdelhamid AS (2020). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic review). 5: CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7388853. PMID 32428300.

- ^ Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, Cifkova R, et al. (2007). "European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary". European Heart Journal. 28 (19): 2375–2414. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm316. PMID 17726041.

- ^ Labarthe, Darwin (2011). "Chapter 17 What Causes Cardiovascular Diseases?". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2nd ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Kris-Etherton PM, Innis S (September 2007). "Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: Dietary Fatty Acids". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 107 (9): 1599–1611 [1603]. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.024. PMID 17936958.

- ^ "Food Fact Sheet - Cholesterol" (PDF). British Dietetic Association. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors". World Heart Federation. 30 May 2017. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Lower your cholesterol". National Health Service. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Nutrition Facts at a Glance - Nutrients: Saturated Fat". Food and Drug Administration. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol". European Food Safety Authority. 2010-03-25. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Healthy diet Fact sheet N°394". May 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom. Position Statement on Fat [Retrieved 2011-01-25].

- ^ Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). "Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ^ "Cholesterol". Irish Heart Foundation. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ^ U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (December 2010). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (PDF) (7th ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Cannon, Christopher; O'Gara, Patrick (2007). Critical Pathways in Cardiovascular Medicine (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 243.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Clarke R, Frost C, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R (1997). "Dietary lipids and blood cholesterol: quantitative meta-analysis of metabolic ward studies". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 314 (7074): 112–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7074.112. PMC 2125600. PMID 9006469.

- ^ Bucher HC, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH (February 1999). "Systematic review on the risk and benefit of different cholesterol-lowering interventions". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 19 (2): 187–195. doi:10.1161/01.atv.19.2.187. PMID 9974397.

- ^ a b Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R (December 2007). "Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths". Lancet. 370 (9602): 1829–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. PMID 18061058. S2CID 54293528.

- ^ Labarthe, Darwin (2011). "Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2 ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Labarthe, Darwin (2011). "Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2nd ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Thijssen MA, Mensink RP (2005). "Fatty acids and atherosclerotic risk". Atherosclerosis: Diet and Drugs. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 170. Springer. pp. 165–94. doi:10.1007/3-540-27661-0_5. ISBN 978-3-540-22569-0. PMID 16596799.

- ^ Boyd NF, Stone J, Vogt KN, Connelly BS, Martin LJ, Minkin S (November 2003). "Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: a meta-analysis of the published literature". British Journal of Cancer. 89 (9): 1672–1685. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601314. PMC 2394401. PMID 14583769.

- ^ a b Hanf V, Gonder U (2005-12-01). "Nutrition and primary prevention of breast cancer: foods, nutrients and breast cancer risk". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 123 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.05.011. PMID 16316809.

- ^ Lof M, Weiderpass E (February 2009). "Impact of diet on breast cancer risk". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 21 (1): 80–85. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32831d7f22. PMID 19125007. S2CID 9513690.

- ^ Freedman LS, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A, Potischman N (Mar–Apr 2008). "Methods of Epidemiology: Evaluating the Fat–Breast Cancer Hypothesis – Comparing Dietary Instruments and Other Developments". Cancer Journal (Sudbury, Mass.). 14 (2): 69–74. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e31816a5e02. PMC 2496993. PMID 18391610.

- ^ Lin OS (2009). "Acquired risk factors for colorectal cancer". Cancer Epidemiology. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 472. pp. 361–72. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_16. ISBN 978-1-60327-491-3. PMID 19107442.