Internet censorship and surveillance by country: Difference between revisions

→{{flag |Lebanon}}: add main |

Wikingtubby (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 646: | Line 646: | ||

* [http://en.rsf.org/ Reporters Without Borders web site]. |

* [http://en.rsf.org/ Reporters Without Borders web site]. |

||

* [http://commons.globalintegrity.org/2008/02/internet-censorship-comparative-study.html Global Integrity: Internet Censorship, A Comparative Study], Jonathan Werve, Global Integrity Commons, 19 February 2008, puts online censorship in cross-country context. |

* [http://commons.globalintegrity.org/2008/02/internet-censorship-comparative-study.html Global Integrity: Internet Censorship, A Comparative Study], Jonathan Werve, Global Integrity Commons, 19 February 2008, puts online censorship in cross-country context. |

||

* [http://www.howtobypassinternetcensorship.org/ ''How to Bypass Internet Censorship''], also known by the titles: ''Bypassing Internet Censorship'' or ''Circumvention Tools'', a [[FLOSS]] Manual, 10 March 2011, 240 pp. |

|||

{{Media country lists}} |

{{Media country lists}} |

||

Revision as of 09:43, 9 June 2011

This article or section recently underwent a major revision or rewrite and may need further review. You can help Wikipedia by assisting in the revision. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. This article was last edited by Wikingtubby (talk | contribs) 12 years ago. (Update timer) |

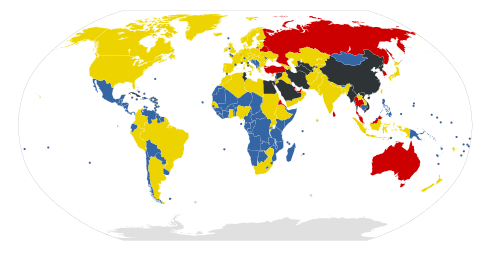

Internet censorship by country provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship or filtering that is occurring in countries around the world.

Classifications

OpenNet Initiative

The OpenNet Initiative (ONI) classifies the magnitude of censorship or filtering occurring in a country in four areas of activity.[1]

The magnitude or level of censorship is classified as follows:

- Pervasive: A large portion of content in several categories is blocked.

- Substantial: A number of categories are subject to a medium level of filtering or many categories are subject to a low level of filtering.

- Selective: A small number of specific sites are blocked or filtering targets a small number of categories or issues.

- Suspected: It is suspected, but not confirmed, that Web sites are being blocked.

- No evidence: No evidence of blocked Web sites, although other forms of controls may exist.

The classifications are done for the following areas of activity:

- Political: Views and information in opposition to those of the current government or related to human rights, freedom of expression, minority rights, and religious movements.

- Social: Views and information perceived as offensive or as socially socially sensitive, often related to sexuality, gambling, or illegal drugs and alcohol.

- Conflict/security: Views and information related to armed conflicts, border disputes, separatist movements, and militant groups.

- Internet tools: e-mail, Internet hosting, search, translation, and Voice-over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services, and censorship or filtering circumvention methods.

Reporters Without Borders

Reporters Without Borders (RWB) maintains a list of the most net-repressive countries that it considers "Internet Enemies" and a second list of countries that are "Under Surveillance" (from 2009) or "Under Watch" (2008).[2]

Countries on the March 2011 Internet Enemies list: Burma, China, Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Vietnam.

Countries on the March 2011 Under Surveillance list: Australia, Bahrain, Belarus, Egypt, Eritrea, France, Libya, Malaysia, Russia, South Korea, Sir Lanka, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela.

Country classifications

The descriptions that follow use both the OpenNet Initiative (ONI) and the Reporters Without Boarders (RWB) classifications.

Pervasive censorship

While there is no universally agreed upon definition of what constitutes "pervasive censorship", Reporters Without Borders maintains an Internet enemies list,[3] while the OpenNet Initiative categorizes some nations as practicing pervasive Internet censorship. Such nations often censor political, social, and other content and may retaliate against citizens who violate the censorship with imprisonment or other sanctions.

Bahrain

Bahrain

- Listed as pervasive in the political and social areas, as substantial in Internet tools, and as selective in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[1]

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

On 5 January 2009 the Ministry of Culture and Information issued an order (Resolution No 1 of 2009)[4] pursuant to the Telecommunications Law and Press and Publications Law of Bahrain that regulates the blocking and unblocking of websites. This resolution requires all ISPs - among other things - to procure and install a website blocking software solution chosen by the Ministry. The Telecommunications Regulatory Authority ("TRA") assisted the Ministry of Culture and Information in the execution of the said Resolution by coordinating the procurement of the unified website blocking software solution. This software solution is operated solely by the Ministry of Information and Culture and neither the TRA nor ISPs have any control over sites that are blocked or unblocked.

Burma

Burma

- Listed as pervasive in the political area and as substantial in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[5]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[2]

Burma (also known as Myanmar) has a very low Internet penetration rate due to both government restrictions on pricing and deliberate lack of facilities and infrastructure.[6] The internet is regulated by the Electronic Act which bans the importing and use of a modem without official permission, and the penalty for violating this is a 15 year prison sentence, as it is considered "damaging state security, national unity, culture, the national economy and law and order." [7] However, internet usage is widely spread in the major cities and towns, with internet cafes and chat rooms. The internet speed is deliberately slowed and a range of websites, from politics to pornography are banned by the Ministry of Post and Telecommunications.

Burma has banned the websites of political opposition groups, sites relating to human rights, and organizations promoting democracy in Burma.[8] During the 2007 anti-government protests, Burma completely shut down all internet links from its country.[9]

China

China

- Listed as pervasive in the political and conflict/security areas and as substantial in social and Internet tools by ONI in June 2009.[1]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[2]

The People's Republic of China blocks or filters Internet content relating to Tibetan independence, Taiwan independence, police brutality, the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, freedom of speech, pornography, some international news sources and propaganda outlets (such as the VOA), certain religious movements (such as Falun Gong), and many blogging websites. At the end of 2007 51 cyber dissidents were reportedly imprisoned in China for their online postings.[10]

Cuba

Cuba

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[2]

- Not categorized by ONI due to lack of data.

Cuba has the lowest ratio of computers per inhabitant in Latin America, and the lowest internet access ratio of all the Western hemisphere.[11] Citizens have to use government controlled "access points", where their activity is monitored through IP blocking, keyword filtering and browsing history checking. The government cites its citizens' access to internet services are limited due to high costs and the American embargo, but there are reports concerning the will of the government to control access to uncensored information both from and to the outer world.[12] The Cuban government continues to imprison independent journalists for contributing reports through the Internet to web sites outside of Cuba.[13]

Salim Lamrani, a professor at Paris Descartes University, has accused Reporters Without Borders with making unsupported and contradictory statements regarding Internet connectivity in Cuba.[14] However, even with the lack of precise figures due to the secretive nature of the regime, testimonials from independent bloggers, activists, and international watchers support the view that it is difficult for most people to access the web and that harsh punishments for individuals that do not follow government policies are the norm.[15][16] The Committee to Protect Journalists has pointed to Cuba as one of the ten most censored countries around the world.[17]

Iran

Iran

- Listed as pervasive in the political, social, and Internet tools areas and as substantial in conflict/security by ONI in June 2009.[1]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[2]

The Islamic Republic of Iran continues to expand and consolidate its technical filtering system, which is among the most extensive in the world. A centralized system for Internet filtering has been implemented that augments the filtering conducted at the Internet service provider (ISP) level.[18] Filtering targets content critical of the government, religion, pornographic websites, political blogs, and women's rights websites, weblogs, and online magazines.[8][19] Bloggers in Iran have been imprisoned for their Internet activities.[20] The Iranian government temporarily blocked access, between 12 May 2006 and January 2009, to video-upload sites such as YouTube.com.[21] Flickr, which was blocked for almost the same amount of time was opened in February 2009. But after 2009 election protests YouTube, Flickr, Twitter, Facebook and many more websites were blocked again.[22]

Kuwait

Kuwait

- Listed as pervasive in the social and Internet tools areas and as selective in political and conflict/security by ONI in June 2009.[1]

The primary target of Internet filtering is pornography and, to a lesser extent, gay and lesbian content. Secular content and Web sites that are critical of Islam are also censored. Some Web sites that are related to religions other than Islam are blocked even though they are not necessarily critical of Islam.[23]

The Kuwait Ministry of Communication regulates ISPs, forcing them to block pornography, anti-religion, anti-tradition, and anti-security websites to "protect the public by maintaining both public order and morality".[24] Both private ISPs and the government take actions to filter the Internet.[25][26]

The Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research (KISR) operates the Domain Name System in Kuwait and does not register domain names which are "injurious to public order or to public sensibilities or otherwise do not comply with the laws of Kuwait".[27] Voice over Internet Protocol is illegal in Kuwait.[28] Not only have many VoIP Web sites been blocked by the MOC, but expatriates have been deported for using or running VOIP services.[29]

In response to several videos declared "offensive to Muslims", Kuwaiti authorities called for the blocking of YouTube[30] and several Kuwaiti Members of Parliament called for stricter restrictions on online content.[31]

Myanmar

Myanmar

- See Burma.

North Korea

North Korea

North Korea is literally cut off from the world, and the Internet is no exception. Only a few hundred thousand citizens in North Korea, representing about 4% of the total population, have access to the Internet, which is heavily censored by the national government.[33] According to the RWB, North Korea is a prime example where all mediums of communication are controlled by the government. According to the RWB, the Internet is used by the North Korean government primarily to spread propaganda. The North Korean network is monitored heavily. All websites are under government control, as is all other media in North Korea.[34]

Oman

Oman

- Listed as pervasive in the social area, as substantial in Internet tools, selective in political, and as no evidence in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[1]

Oman engages in extensive filtering of pornographic Web sites, gay and lesbian content, content that is critical of Islam, content about illegal drugs, and anonymizer sites used to circumvent blocking. There is no evidence of technical filtering of political content, but laws and regulations restrict free expression online and encourage self-censorship.[35]

Qatar

Qatar

- Listed as pervasive in the social and Internet tools areas and selective in political and conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[1]

Qatar is the second most connected country in the Arab region, but Internet users have heavily censored access to the Internet. Qatar filters pornography, political criticism of Gulf countries, material, gay and lesbian content, sexual health resources, dating and escort services, and privacy and circumvention tools. Political filtering is highly selective, but journalists self-censor on sensitive issues such as government policies, Islam, and the ruling family.[36]

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

- Listed as pervasive in the social and Internet tools areas, as substantial in political, and as selective in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[1]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[2]

Saudi Arabia directs all international Internet traffic through a proxy farm located in King Abdulaziz City for Science & Technology. Content filtering is implemented there using software by Secure Computing.[37] Additionally, a number of sites are blocked according to two lists maintained by the Internet Services Unit (ISU):[38] one containing "immoral" (mostly pornographic) sites, the other based on directions from a security committee run by the Ministry of Interior (including sites critical of the Saudi government). Citizens are encouraged to actively report "immoral" sites for blocking, using a provided Web form. The legal basis for content-filtering is the resolution by Council of Ministers dated 12 February 2001.[39] According to a study carried out in 2004 by the OpenNet Initiative: "The most aggressive censorship focused on pornography, drug use, gambling, religious conversion of Muslims, and filtering circumvention tools."[37]

South Korea

South Korea

- Listed as pervasive in the conflict/security area, as substantial in social, and as no evidence in political and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[1]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

South Korea is a world leader in Internet and broadband penetration, but its citizens do not have access to a free and unfiltered Internet. South Korea’s government maintains a wide-ranging approach toward the regulation of specific online content and imposes a substantial level of censorship on elections-related discourse and on a large number of Web sites that the government deems subversive or socially harmful.[40] The policies are particularly strong toward suppressing anonymity in the Korean internet.

In 2007, numerous bloggers were censored and their posts deleted by police for expressing criticism of, or even support for, presidential candidates. This even lead to some bloggers being arrested by the police.[41]

South Korea uses IP address blocking to ban web sites considered sympathetic to North Korea.[8][42] Illegal websites, such as those offering unrated games, pornography, and gambling, are also blocked.

Syria

Syria

- Listed as pervasive in the political and Internet tools areas, and as selective in social and conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[1]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[2]

Syria has banned websites for political reasons and arrested people accessing them. In addition to filtering a wide range of Web content, the Syrian government monitors Internet use very closely and has detained citizens "for expressing their opinions or reporting information online." Vague and broadly worded laws invite government abuse and have prompted Internet users to engage in self-censoring and self-monitoring to avoid the state's ambiguous grounds for arrest.[8][43]

Tunisia

Tunisia

- Listed as pervasive in the political, social, and Internet tools areas and as selective in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[1]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

Tunisia has blocked thousands of websites (such as pornography, mail, search engine cached pages, online documents conversion and translation services) and peer-to-peer and FTP transfer using a transparent proxy and port blocking. Cyber dissidents including pro-democracy lawyer Mohammed Abbou have been jailed by the Tunisian government for their online activities.[44]

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

- Listed as pervasive in the political area and as selective in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[1]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[2]

Internet usage in Turkmenistan is under tight control of the government. Turkmen got their news through satellite television until 2008 when the government decided to get rid of satellites, leaving Internet as the only medium where information could be gathered. The Internet is monitored thoroughly by the government and websites run by human rights organizations and news agencies are blocked. Attempts to get around this censorship can lead to grave consequences.[45]

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates

- Listed as pervasive in the social and Internet tools areas, as substantial in political, and as selective in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[1]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

The United Arab Emirates forcibly censors the Internet using Secure Computing's solution. The nation's ISPs Etisalat and du (telco) ban pornography, politically sensitive material, all Israeli domains,[46] and anything against the perceived moral values of the UAE. All or most VoIP services are blocked. The Emirates Discussion Forum (Arabic: منتدى الحوار الإماراتي), or simply uaehewar.net, has been subjected to multiple censorship actions by UAE authorities.[47]

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[2]

Uzbekistan prevents access to websites regarding banned Islamic movements, independent media, NGOs, and material critical of the government's human rights violations.[8] Some Internet cafes in the capital have posted warnings that users will be fined for viewing pornographic websites or website containing banned political material.[48] The main VoIP protocols SIP and IAX used to be blocked for individual users; however, as of July 2010, blocks were no longer in place. Facebook was blocked for few days in 2010.[49]

Vietnam

Vietnam

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[2]

The main networks in Vietnam prevent access to websites critical of the Vietnamese government, expatriate political parties, and international human rights organizations, among others.[8] Online police reportedly monitor Internet cafes and cyber dissidents have been imprisoned for advocating democracy.[50]

Yemen

Yemen

- Listed as pervasive in the social and Internet tools areas, as substantial in political, and as selective in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[1]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2008 and 2009, but not in 2010 or 2011.[2]

Yemen censors pornography, nudity, gay and lesbian content, escort and dating services, sites displaying provocative attire, Web sites which present critical reviews of Islam and/or attempt to convert Muslims to other religions, or content related to alcohol, gambling, and drugs.[51]

Yemen’s Ministry of Information declared in April 2008 that the penal code will be used to prosecute writers who publish Internet content that "incites hatred" or "harms national interests".[52] Yemen's two ISPs, YemenNet and TeleYemen, block access to gambling, adult, sex education, and some religious content.[8] The ISP TeleYemen (aka Y.Net) prohibits "sending any message which is offensive on moral, religious, communal, or political grounds" and will report "any use or attempted use of the Y.Net service which contravenes any applicable Law of the Republic of Yemen". TeleYemen reserves the right to control access to data stored in its system “in any manner deemed appropriate by TeleYemen.”[53]

In Yemen closed rooms or curtains that might obstruct views of the monitors are not allowed in Internet cafés, computer screens in Internet cafés must be visible to the floor supervisor, police have ordered some Internet cafés to close at midnight, and demanded that users show their identification cards to the café operator.[54]

Substantial censorship

This classification includes countries where a number of categories are subject to a medium level of filtering or many categories are subject to a low level of filtering.

Armenia

Armenia

- Listed as substantial in the political area and as selective in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in November 2010.[1]

Access to the Internet in Armenia is largely unfettered, although evidence of second- and third-generation filtering is mounting. Armenia’s political climate is volatile and largely unpredictable. In times of political unrest, the government has not hesitated to put in place restrictions on the Internet as a means to curtail public protest and discontent.[55]

Ethiopia

Ethiopia

- Listed as substantial in the political and conflict/security areas, as selective in social, and as no evidence in Internet tools by ONI in September 2009.[1]

Ethiopia has implemented a largely political filtering regime that blocks access to popular blogs and the Web sites of many news organizations, dissident political parties, and human rights groups. However, much of the media content that the government is attempting to censor can be found on sites that are not banned. The authors of the blocked blogs have in many cases continued to write for an international audience, apparently without sanction. However, Ethiopia is increasingly jailing journalists, and the government has shown a growing propensity toward repressive behavior both off- and online. Censorship is likely to become more extensive as Internet access expands across the country.[56]

Gaza and the West Bank

Gaza and the West Bank

- Listed as substantial in the social area and as no evidence in political, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in August 2009.[1]

Access to Internet in the Palestinian territories remains relatively open, although social filtering of sexually explicit content has been implemented in Gaza. Internet in the West Bank remains almost entirely unfiltered, save for a single news Web site that was banned for roughly six months starting in late 2008. Media freedom is constrained in Gaza and the West Bank by the political upheaval and internal conflict as well as by the Israeli occupation and forces.[57]

Pakistan

Pakistan

- Listed as substantial in the social and conflict/security areas, as selective in Internet tools, and as suspected in political by ONI in December 2010.[1]

In late 2010 Pakistanis enjoyed unimpeded access to most sexual, political, social, and religious content on the Internet. Although the Pakistani government does not employ a sophisticated blocking system, a limitation which has led to collateral blocks on entire domains such as Blogspot.com and YouTube.com, it continues to block Web sites containing content it considers to be blasphemous, anti-Islamic, or threatening to internal security. Pakistan has blocked access to websites critical of the government.[58]

Sudan

Sudan

- Listed as substantial in the social and Internet tools areas and as selective in political, and as no evidence in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[1]

Sudan openly acknowledges filtering content that transgresses public morality and ethics or threatens order. The state's regulatory authority has established a special unit to monitor and implement filtration; this primarily targets pornography and, to a lesser extent, gay and lesbian content, dating sites, provocative attire, and many anonymizer and proxy Web sites.[59]

Thailand

Thailand

- Listed as substantial in the social area, as selective in political and Internet tools, and as no evidence in conflict/security by ONI in May 2007.[1]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

- Listed as "Not Free" in the Freedom on the Net 2011 report by Freedom House, which cites substantial political censorship and the arrest of bloggers and other online users.[60]

Prior to the September 2006 military coup d'état most Internet censorship in Thailand was focused on blocking pornographic websites. The following years have seen a constant stream of sometimes violent protests, regional unrest,[61] emergency decrees,[62] a new cybercrimes law,[63] and an updated Internal Security Act.[64] And year by year Internet censorship has grown, with its focus shifting to lèse majesté, national security, and political issues. Estimates put the number of websites blocked at over 110,000 and growing in 2010.[65]

Reasons for blocking:

Prior to

2006[66]

2010[67]

Reason11% 77% lèse majesté content (content that defames, insults, threatens, or is unflattering to the King, includes national security and some political issues) 60% 22% pornographic content 2% <1% content related to gambling 27% <1% copyright infringement, illegal products and services, illegal drugs, sales of sex equipment, prostitution, …

According to the Associated Press, the Computer Crime Act has contributed to a sharp increase in the number of lèse majesté cases tried each year in Thailand.[68] While between 1990 and 2005, roughly five cases were tried in Thai courts each year, since that time about 400 cases have come to trial--a 1,500 percent increase.[68]

Selective censorship

This classification includes countries where a small number of specific sites are blocked or filtering targets a small number of categories or issues.

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

- Listed as selective in the political and social areas and as no evidence in conflict/security and Internet tools by ONI in November 2009.[1]

The Internet in Azerbaijan remains largely free from direct censorship, although there is evidence of second- and third-generation controls.[69]

Belarus

Belarus

- Listed as selective in the political, social, conflict/security and Internet tools areas by ONI in May 2007.[1]

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

The Belarus government has moved to second- and third-generation controls to manage its national information space. Control over the Internet is centralized with the government-owned Beltelecom managing the country’s Internet gateway. Regulation is heavy with strong state involvement in the telecommunications and media market. Most users who post online media practice a degree of self-censorship prompted by fears of regulatory prosecution. The president has established a strong and elaborate information security policy and has declared his intention to exercise strict control over the Internet under the pretext of national security. The political climate is repressive and opposition leaders and independent journalists are frequently detained and prosecuted.[70]

Gambia

Gambia

- Not individually classified by ONI,[1] but classified as selective based on the limited descriptions in the ONI profile for the sub-Saharan Africa region.[71]

Gambia is a particularly egregious offender of the right to freedom of expression: in 2007 a Gambian journalist living in the US was convicted of sedition for an article published online; she was fined USD12,000;[72] in 2006 the Gambian police ordered all subscribers to an online independent newspaper to report to the police or face arrest.[73]

Georgia

Georgia

- Listed as selective in the political and conflict/security areas and asno evidence in social and Internet tools by ONI in November 2010.[1]

Access to Internet content in Georgia is largely unrestricted as the legal constitutional framework, developed after the 2003 Rose Revolution, established a series of provisions that should, in theory, curtail any attempts by the state to censor the Internet. At the same time, these legal instruments have not been sufficient to prevent limited filtering on corporate and educational networks. Georgia’s dependence on international connectivity makes it vulnerable to upstream filtering, evident in the March 2008 blocking of YouTube by Turk Telecom.[74]

Georgia blocked all websites with addresses ending in .ru (top-level domain for Russian Federation) after South Ossetia War in 2008.[75]

India

India

- Listed as selective in the conflict/security and Internet tools areas and as no evidence in political and social by ONI in May 2007.[1]

ONI states that:

As a stable democracy with strong protections for press freedom, India’s experiments with Internet filtering have been brought into the fold of public discourse. The selective censorship of Web sites and blogs since 2003, made even more disjointed by the non-uniform responses of Internet service providers (ISPs), has inspired a clamor of opposition. Clearly government regulation and implementation of filtering are still evolving. … Amidst widespread speculation in the media and blogosphere about the state of filtering in India, the sites actually blocked indicate that while the filtering system in place yields inconsistent results, it nevertheless continues to be aligned with and driven by government efforts. Government attempts at filtering have not been entirely effective, as blocked content has quickly migrated to other Web sites and users have found ways to circumvent filtering. The government has also been criticized for a poor understanding of the technical feasibility of censorship and for haphazardly choosing which Web sites to block. The amended IT Act, absolving intermediaries from being responsible for third-party created content, could signal stronger government monitoring in the future.[76]

Italy

Italy

- Listed as selective in the social area and as no evidence in political, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[1]

Italy bans the use of foreign bookmakers over the Internet by mandating certain edits to DNS host files of Italian ISPs.[77][78] Italy is also blocking access to websites containing child pornography.[79] In 2008, Italy blocked also The Pirate Bay website[80][81] for some time, basing this censorship on a law on electronic commerce. As of 25 May 2010[update], access to The Pirate Bay is blocked again.

Jordan

Jordan

- Listed as selective in the political area and as no evidence in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in August 2009.[1]

Censorship in Jordan is relatively light, with filtering selectively applied to only a small number of sites. However, media laws and regulations encourage some measure of self-censorship in cyberspace, and citizens have reportedly been questioned and arrested for Web content they have authored. Censorship in Jordan is mainly focused on political issues that might be seen as a threat to national security due to the nation's close proximity to regional hotspots like Israel, Iraq, Lebanon, and the Palestinian territories.[82]

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan

- Listed as selective in the political and social areas and as no evidence in conflict/security and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[1]

Kazakhstan uses its significant regulatory authority to ensure that all Internet traffic passes through infrastructure controlled by the dominant telecommunications provider KazakhTelecom. Selective content filtering is widely used, and second- and third-generation control strategies are evident. Independent media and bloggers reportedly practice self-censorship for fear of government reprisal. The technical sophistication of the Kazakhstan Internet environment is evolving and the government’s tendency toward stricter online controls warrant closer examination and monitoring.[83]

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan

- Listed as selective in the political and social areas and as no evidence in conflict/security and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[1]

Access to the Internet in Kyrgyzstan has deteriorated as heightened political tensions have led to more frequent instances of second- and third-generation controls. The government has become more sensitive to the Internet’s influence on domestic politics and enacted laws that increase its authority to regulate the sector.[84][83]

Liberalization of the telecommunications market in Kyrgyzstan has made the Internet affordable for the majority of the population. However, Kyrgyzstan is an effectively cyberlocked country dependent on purchasing bandwidth from Kazakhstan and Russia. The increasingly authoritarian regime in Kazakhstan is shifting toward more restrictive Internet controls, which is leading to instances of ‘‘upstream filtering’’ affecting ISPs in Kyrgyzstan.[84]

Libya

Libya

- Listed as selective in the political area and as no evidence in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in August 2009.[1]

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

In the past few years, Internet filtering in Libya has become more selective, focusing on a few political opposition Web sites. This relatively lenient filtering policy coincides with what is arguably a trend toward greater openness and increasing freedom of the press. However, the legal and political climate continues to encourage self-censorship in online media.[85]

In 2006 Reporters Without Borders removed Libya from their list of Internet enemies after a fact-finding visit found no evidence of Internet censorship.[3] ONI’s 2007-2008 technical test results contradicted that conclusion, however.[85]

Moldova

Moldova

- Listed as selective in the political area and as no evidence in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[1]

While State authorities have interfered with mobile and Internet connections in an attempt to silence protestors and influence the results of elections, Internet users in Moldova enjoy largely unfettered access despite the government’s restrictive and increasingly authoritarian tendencies. Evidence of second- and third-generation controls is mounting. Although filtering does not occur at the backbone level, the majority of filtering and surveillance takes place at the sites where most Moldovans access the Internet: Internet cafe´ s and workplaces. Moldovan security forces have developed the capacity to monitor the Internet, and national legislation concerning ‘‘illegal activities’’ is strict.[86]

Morocco

Morocco

- Listed as selective in the social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas and as no evidence in political by ONI in August 2009.[1]

Internet access in Morocco is, for the most part, open and unrestricted. Morocco’s Internet filtration regime is relatively light and focuses on a few blog sites, a few highly visible anonymizers, and for a brief period in May 2007, the video sharing Web site YouTube.[87] ONI testing revealed that Morocco no longer filters a majority of sites in favor of independence of the Western Sahara, which were previously blocked. The filtration regime is not comprehensive, that is to say, similar content can be found on other Web sites that are not blocked. On the other hand, Morocco has started to prosecute Internet users and bloggers for their online activities and writings.[88]

Russia

Russia

- Listed as selective in the political and social areas and as no evidence in conflict/security and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[1]

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

The absence of overt state-mandated Internet filtering in Russia has led some observers to conclude that the Russian Internet represents an open and uncontested space. In fact, the opposite is true. The Russian government actively competes in Russian cyberspace employing second- and third-generation strategies as a means to shape the national information space and promote pro-government political messages and strategies. This approach is consistent with the government’s strategic view of cyberspace that is articulated in strategies such as the doctrine of information security. The DoS attacks against Estonia (May 2007) and Georgia (August 2008) may be an indication of the government’s active interest in mobilizing and shaping activities in Russian cyberspace.[89]

In 2004 Russia pressured Lithuania and in 2006 Sweden into shutting down the Kavkaz Center website, a site that supports creation of a Sharia state in North Caucasus and hosts videos on terrorist attacks on Russian forces in North Caucasus.[90][91][92]

Singapore

Singapore

- Listed as selective in the social area and as no evidence in political, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in May 2007.[1]

The Republic of Singapore engages in minimal Internet filtering, blocking only a small set of pornographic Web sites as a symbol of disapproval of their contents. However, the state employs a combination of licensing controls and legal pressures to regulate Internet access and to limit the presence of objectionable content and conduct online.[93]

In 2005 and 2006 three people were arrested and charged with sedition for posting racist comments on the Internet, of which two have been sentenced to imprisonment.[94] Some ISPs also block internet content related to recreational drug use. Singapore's government-run Media Development Authority maintains a confidential list of blocked websites that are inaccessible within the country. The Media Development Authority exerts control over Singapore's three ISPs to ensure that blocked content is entirely inaccessible.

Tajikistan

Tajikistan

- Listed as selective in the political area and as no evidence as in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[1]

Internet penetration remains low in Tajikistan because of widespread poverty and the relatively high cost of Internet access. Internet access remains largely unrestricted, but emerging second-generation controls have threatened to erode these freedoms just as Internet penetration is starting to have an impact on political life in the country. In the run-up to the 2006 presidential elections, ISPs were asked to voluntarily censor access to an opposition Web site, and other second-generation controls have begun to emerge.[95]

Turkey

Turkey

- Listed as selective in the political, social, and Internet tools areas and as no evidence as in conflict/security by ONI in December 2010.[1]

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

The Turkish government has implemented legal and institutional reforms driven by the country’s ambitions to become a European Union member state, while at the same time demonstrating its high sensitivity to defamation and other ‘‘inappropriate’’ online content, which has resulted in the closure of a number of local and international Web sites. All Internet traffic passes through Turk Telecom’s infrastructure, allowing centralized control over online content and facilitating the implementation of shutdown decisions.[96]

Many minor and major websites in Turkey have been subject to censorship. As of June 2010 more than 8000 major and minor websites were banned, most of them pornographic and mp3 sharing sites.[97] Other Among the web sites banned are the prominent sites Youporn, Megaupload, Deezer, Tagged, Slide, and ShoutCast. However, blocked sites are often available using proxies or by changing DNS servers. The Internet Movie Database escaped being blocked due to a misspelling of its domain name, resulting in a futile ban on www.imbd.com.[98]

In October 2010, the ban of Youtube was lifted. But a range of IP addresses used by Google remained blocked, thus access to Google Apps hosted sites, including all Google App Engine powered sites and some of the Google services, remained blocked.

Under new regulations announced on 22 February 2011 and scheduled to go into effect on 22 August 2011, the Information Technologies Board (BTK), an offshoot of the prime minister’s office, will require that all computers select one of four levels of content filtering (family, children, domestic, or standard) in order to gain access to the Internet.[99]

Under surveillance

Countries in this category are on the RWB Under Surveillance list, but are not individually classified by or are classified as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI.[1]

Australia

Australia

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for Australia and New Zealand.[100]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

Australia does not allow content that would be classified "RC" (Refused Classification or banned) or "X18+" (hardcore non-violent pornography or very hardcore shock value) to be hosted within Australia and considers such content "prohibited"/"potentially prohibited" outside Australia; it also requires most other age-restricted content sites to verify a user's age before allowing access. Since January 2008 material that would be likely to be classified "R18+" or "MA15+" and which is not behind such an age verification service (and, for MA15+, which also meets other criteria such as provided for profit, or contains certain media types) also fits the category of "prohibited" or "potentially prohibited". The regulator ACMA can order local sites which do not comply taken down, and overseas sites added to a blacklist provided to makers of PC-based filtering software.

Australia is classified as "under surveillance" by Reporters Without Borders due to the internet filtering legislation proposed by Minister Stephen Conroy. Regardless, as of August 2010 and the outcome of the 2010 election, it would be highly unlikely for the filter to pass the Senate if proposed due to the close numbers of seats held by Labor and the Coalition, who Joe Hockey says do not support it.[101]

Egypt

Egypt

- Listed as selective in the political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas by ONI in August 2009.[1]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

The Internet in Egypt was not directly censored under President Hosni Mubarak, but his regime kept watch on the most critical bloggers and regularly arrested them. At the height of the uprising against the dictatorship, in late January 2011, the authorities first filtered pictures of the repression and then cut off Internet access entirely in a bid to stop the revolt spreading. The success of the revolution offers a chance to entrench greater freedom of expression in Egypt, especially online. At the same time success in this effort is not certain and as a result Reporters Without Borders has placed Egypt "under surveillance".[102]

Due to fears of terrorism, the government increased web surveillance in 2007. To connect to wireless internet in a public place, such as a cybercafé, a person must give up a lot of personal information, such as a phone number or ID #, making it hard for citizens to express themselves freely.[7]

During the 2011 Egyptian protests, Egypt shut itself off from the rest of the Internet. About 3500 Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) routes to Egyptian networks were shut down from about 22:10 to 22:35 UTC 27 January, imposing what was an almost complete block of the Internet in Egypt.[103][104] The heavy filtering at the height of the revolution has reportedly ended.

Eritrea

Eritrea

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

Eritrea has not set up a widespread automatic Internet filtering system, but it does not hesitate to order blocking of several diaspora websites critical of the regime. Access to these sites is blocked by two of the Internet service providers, Erson and Ewan, as are pornographic websites and YouTube. Self-censorship is said to be widespread.[105]

France

France

- Listed as no evidence in the political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas by ONI in November 2010.[1]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

France continues to promote freedom of the press and speech online by allowing unfiltered access to most content, apart from limited filtering of child pornography and web sites that promote terrorism, or racial violence and hatred. The French government has undertaken numerous measures to protect the rights of Internet users, including the passage of the Loi pour la Confiance dans l’Économie Numérique (LCEN, Law for Trust in the Digital Economy) in 2004. However, the passage of a new copyright law threatening to ban users from the Internet upon their third violation has drawn much criticism from privacy advocates as well as the European Union (EU) parliament.[106]

With the implementation of the "three-strikes" legislation and a law providing for the administrative filtering of the web and the defense of a "civilized" Internet, 2010 was a difficult year for Internet freedom in France. The offices of several online media firms and their journalists were targeted for break-ins and court summons and pressured to identify their sources. As a result, France has been added to Reports Without Borders list of "Countries Under Surveillance".[107]

Malaysia

Malaysia

- Listed as no evidence in the political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas by ONI in May 2007.[1]

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

There have been mixed messages and confusion regarding Internet censorship in Malaysia. Internet content is officially uncensored, and civil liberties assured, though on numerous occasions the government has been accused of filtering politically sensitive sites. Any act that curbs internet freedom is theoretically contrary to the Multimedia Act signed by the government of Malaysia in the 1990s. However, pervasive state controls on traditional media spill over to the Internet at times, leading to self-censorship and reports that the state investigates and harasses bloggers and cyber-dissidents.[108]

In April 2011, prime minister Najib Razak repeated promises that Malaysia will never censor the Internet.[109]

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

Several political and news websites, including tamilnet.com and lankanewsweb.com have been blocked within the country.[110] The Sri Lanka courts have ordered hundreds of adult sites blocked to "protect women and children".[111][112]

Venezuela

Venezuela

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB in 2011.[2]

In December 2010, the government of Venezuela led by Hugo Chavez passed a law for the regulation of Internet content. The National Assembly, which is controlled by a pro-Chavez majority, approved a law named "Social Responsibility in Radio, Television and Electronic Media" (Ley de Responsabilidad Social en Radio, Televisión y Medios Electrónicos). The law is intended to exercise control over content that could "entice felonies", "create social distress", or "question the legitimate constituted authority". The law indicates that the website's owners will be responsible for any information and contents published, and that they will have to create mechanisms that could restrict without delay the distribution of content that could go against the aforementioned restrictions. The fines for individuals who break the law will be of the 10% of the person's last year's income. The law was received with criticism from the opposition on the grounds that it is a violation of freedom of speech protections stipulated in the Venezuelan constitution, and that it encourages censorship and self-censorship.[113]

No evidence of censorship

This classification includes countries where there is no evidence of blocked Web sites or other technical filtering, although other controls such as voluntary filtering, self-censorship, and other types of private action to limit child pornography, hate speech, defamation or theft of intellectual property may exist.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in May 2007.[1]

Only about 1/10 of 1 percent of Afghans are online, thus limiting the Internet as a means of expression. Freedom of expression is inviolable under the Afghanistan Constitution, and every Afghan has the right to print or publish topics without prior submission to state authorities. However, the limits of the law are clear: under the Constitution no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam. The December 2005 Media Law includes bans on four broad content categories: the publication of news contrary to Islam and other religions; slanderous or insulting materials concerning individuals; matters contrary to the Afghan Constitution or criminal law; and the exposure of the identities of victims of violence. Proposed additions to the law would ban content jeopardizing stability, national security, and territorial integrity of Afghanistan; false information that might disrupt public opinion; promotion of any religion other than Islam; and "material which might damage physical well-being, psychological and moral security of people, especially children and the youth.[114]

The Electronic Frontier Foundation reported that the Afghan Ministry of Communications mandated in June 2010 that all Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in Afghanistan filter Facebook, Gmail, Twitter, YouTube and websites related to alcohol, gambling and sex. They are also trying or blocking websites which are “immoral” and against the traditions of the Afghan people.[115] However, executives at Afghan ISPs said this was the result of a mistaken announcement by Ariana Network Service, one of the country's largest ISPs. An executive there said that while the government intends to censor pornographic content and gambling sites, social networking sites and email services are not slated for filtering. As of July 2010, enforcement of Afghanistan's restrictions on "immoral" content was limited, with internet executives saying the government didn't have the technical capacity to filter internet traffic.[116]

Algeria

Algeria

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in August 2009.[1]

Internet access in Algeria is not restricted by technical filtering. However, the state controls the Internet infrastructure and regulates content by other means. Internet users and Internet service providers (ISPs) can face criminal penalties for posting or allowing the posting of material deemed contrary to public order or morality.[117]

Belgium

Belgium

- Not individually classified by ONI, but included in the regional overview for Europe.[118]

Belgian internet providers Belgacom, Telenet, Base, Scarlet, EDPnet, Dommel, Proximus, Mobistar, Mobile Vikings, Tele2, and Versatel have started filtering several websites on DNS level since April 2009.[119] People who browse the internet using one of these providers and hit a blocked website are redirected to a page that claims that the content of the website is illegal under Belgian law and therefore blocked.[120]

Brazil

Brazil

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for Latin America.[121]

Brazilian legislation restricts the freedom of expression (Paim Law), directed especially to publications considered racist (such as neo-nazi sites). The Brazilian Constitution also prohibits anonymity of journalists.

Canada

Canada

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for the United States and Canada.[122]

Information, such as names of young offenders or information on criminal trials subject to publication bans, which the government is actively attempting to keep out of Canadian broadcast and print media is sometimes available to Canadian users via the Internet from sites hosted outside Canada.

Project Cleanfeed Canada (cybertip.ca) decides what sites are child pornographic in nature and transmits those lists to the voluntarily participating ISPs who can then block the pages for their users. However, some authors, bloggers and digital rights lawyers argue that they are accountable to no one and could be adding non pornographic sites to their list without public knowledge.[123]

Chile

Chile

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for Latin America.[121]

Many educational institutions (universities and schools) block the access to websites like YouTube, Fotolog, Flickr, Blogger, Rapidshare, Twitter and Facebook, depending of the institution; in some cases also popular portals like Terra.cl, LUN.com, EMOL.com are also blocked; pornography, especially any kind of child pornographic website is blocked.[124] The Chilean Government also block the access in their computers to blogs or electronic versions of the local newspapers with opinions against the Government or the ruling coalition, for example, during the first days of Transantiago or the 2006 Student Protests.

Colombia

Colombia

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for Latin America.[121]

Colombia blocks several websites as part of its Internet Sano program. In December 2009, an internaute was sent to prison for threatening president Álvaro Uribe's sons.[125]

Czech Republic

Czech Republic

- Not individually classified by ONI.

Since 2008, mobile operators T-Mobile[126] and Vodafone[127][128] pass mobile and fixed Internet traffic through Cleanfeed, which uses data provided by the Internet Watch Foundation to identify pages believed to contain indecent photographs of children, and racist materials.

On 13 August 2009, Telefónica O2 Czech Republic, Czech DSL incumbent and mobile operator, started to block access to sites listed by Internet Watch Foundation. The company said it wanted to replace the list with data provided by Czech Police.[129] The rollout of the blocking system attracted public attention due to serious network service difficulties and many innocent sites mistakenly blocked. The concrete blocking implementation is unknown but it is believed that recursive DNS servers provided by the operator to its customers have been modified to return fake answers diverting consequent TCP connections to an HTTP firewall.[130]

On 6 May 2010, T-Mobile Czech Republic officially announced[131] that it was starting to block web pages promoting child pornography, child prostitution, child trafficking, pedophilia and illegal sexual contact with children. T-Mobile claimed that its blocking was based on URLs from the Internet Watch Foundation list and on individual direct requests made by customers.

Denmark

Denmark

- Not individually classified by ONI, but included in the regional overview for the Nordic Countries.[132]

Denmark's biggest Internet service provider TDC A/S launched a DNS-based child pornography filter on 18 October 2005 in cooperation with the state police department and Save the Children, a charity organisation. Since then, all major providers have joined and as of May 2006, 98% of the Danish Internet users are restricted by the filter.[133] The filter caused some controversy in March 2006, when a legal sex site named Bizar.dk was caught in the filter, sparking discussion about the reliability, accuracy and credibility of the filter.[134] Also, as of 18 October 2005, TDC A/S has blocked access to AllOfMP3.com, a popular MP3 download site, through DNS filtering.[135]

4 February 2008 a Danish court has ordered the Danish ISP Tele2 to shutdown access to the filesharing site thepiratebay.org for all its Danish users.[136]

On 23 December 2008, the list of 3,863 sites filtered in Denmark was released by Wikileaks.[137]

Estonia

Estonia

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for the Commonwealth of Independent States.[138]

Early 2010 Estonia started DNS filtering of "remote gambling sites" conflicting the renewed Gambling Act (2008). Estonia Implements Gambling Act. So far (2010-03-01) only one casino has obtained the proper license. The Gambling Act says - servers for the "legal" remote gambling must be physically located in Estonia. The latest local news is that Tax and Customs Board has compiled a blocking list containing 175 sites which ISPs are to enforce. Previously Internet was completely free of censorship in Estonia.

Fiji

Fiji

- Not individually classified by ONI.

In May 2007 it was reported that the military in Fiji had blocked access to blogs critical of the regime.[139]

Finland

Finland

- Not individually classified by ONI, but included in the regional overview for the Nordic Countries.[132]

In 2006, a new copyright law known as Lex Karpela set some restrictions on publishing information regarding copy protection schemes.

Also in 2006 the government started Internet censorship by delivering Finnish ISPs a secret blocking list maintained by Finnish police.[140] Implementation of the block was voluntary, but some ISPs implemented it. The list was supposed to contain only sites with child pornography, but ended up also blocking, among others, the site lapsiporno.info that criticized the move towards censorship and listed sites that were noticed to have been blocked.[141]

In 2008 a government-sponsored report has considered establishing similar filtering in order to curb online gambling.[142]

Germany

Germany

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in December 2010.[1]

Occasional take down requests and access restrictions are imposed on German ISPs, usually to protect minors or to suppress hate speech and extremism. In April 2009, the German government signed a bill that would implement large-scale filtering of child pornography Web sites, with the possibility for later expansion.[143]

Ghana

Ghana

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for sub-Saharan Africa.[71]

In 2002 the government of Ghana censored internet media coverage of tribal violence in Northern Ghana.[144]

Iceland

Iceland

- Not individually classified by ONI, but included in the regional overview for the Nordic Countries.[132]

Censorship is prohibited by the Icelandic Constitution and there is a strong tradition of protecting freedom of expression that extends to the use of the Internet.[145] However, questions about how best to protect children, fight terrorism, prevent liable, and protect the rights of copyright holders are ongoing in Iceland as they are in much of the world.

The five Nordic countries—Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Iceland—are central players in the European battle between file sharers, rights holders, and Internet service providers (ISPs). While each country determines its own destiny, the presence of the European Union (EU) is felt in all legal controversies and court cases. Iceland, while not a member of the EU, is part of the European Economic Area (EEA) and has agreed to enact legislation similar to that passed in the EU in areas such as consumer protection and business law.[132]

Internet service providers in Iceland use filters to block Web sites distributing child pornography. Iceland's ISPs in cooperation with Barnaheill—Save the Children Iceland participate in the International Association of Internet Hotlines (INHOPE) project. Suspicious links are reported by organizations and the general public and passed on to relevant authorities for verification.[132]

Iraq

Iraq

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in August 2009.[1]

Internet access in Iraq remains largely unfettered, but this is likely to change, as the authorities have initiated measures to censor Internet content and monitor online activities. In addition, the government has launched legal offensives against independent news media and Web sites.[146]

Ireland

Ireland

- Not individually classified by ONI, but see the entry for the United Kingdom below.

Israel

Israel

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in August 2009.[1]

The Orthodox Jewish parties in Israel proposed an internet censorship legislation would only allow access to adult-content Internet sites for users who identify themselves as adults and request not to be subject to filtering. In February 2008 the law passed in its first of three votes required,[147] however, it was been rejected by the government's legislation committee on 12 July 2009.[148]

Lebanon

Lebanon

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in August 2009.[1]

Internet traffic in Lebanon is not subject to technical filtering, but poor infrastructure, few household computers, low Internet penetration rates, and the cost high of connectivity, remain serious challenges. Some Internet café operators prevent their clients from accessing objectionable content such as pornography, however, there is no evidence that these practices are required or encouraged by the state. Lebanese law permits the censoring of pornography, political opinions, and religious materials when considered a threat to national security.[149]

Malawi

Malawi

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for sub-Saharan Africa.[71]

Malawi prohibits the publication or transmission of anything “that could be useful to the enemy,” as well as religiously offensive and obscene material. Malawi participates in regional efforts to combat cybercrime: the East African Community (consisting of Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda) and the South African Development Community (consisting of Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) have both enacted plans to standardize cybercrime laws throughout their regions.[71]

Mexico

Mexico

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for Latin America.[121]

In May 2009, the Mexican Federal Electoral Institute (IFE), asked YouTube to remove a parody of Fidel Herrera, governor of the state of Veracruz. Negative advertising in political campaigns is prohibited by present law, although the video appears to be made by a regular citizen which would make it legal. It was the first time a Mexican institution intervened directly with the Internet.

Nepal

Nepal

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in May 2007.[1]

In 2007 Nepali journalists reported virtually unconditional freedom of the press, including the Internet, and ONI’s testing revealed no evidence that Nepal imposes technological filters on the Internet.[150]

Netherlands

Netherlands

- Not individually classified by ONI.

Since 2007 one major ISP, UPC Netherlands, appears to block access on DNS level to sites the provider claims to contain child pornography.[151] In 2008 Ernst Hirsch Ballin, then Minister of Justice, proposed a plan to regulate the blocking of websites known to contain child pornography. The list would have been compiled by the National Police Forces (KLPD) and would not contain sites hosted in EU countries.[152] Providers would not be forced to use it since that would be unconstitutional according to a research done by the governmental Scientific Research and Documentation Center (WODC) commissioned by the Ministry of Justice.[153] It never gained traction and was not backed by any other major internet providers. In 2011 the plan was pulled by Ivo Opstelten after the Werkgroep Blokkeren Kinderporno concluded it would not be effective since the amount of websites containing child pornography drastically lowered in 2010 and that the sharing of the material was no longer done by conventional websites but other services.[154] The House of Representatives reaffirmed this by voting against the filter later that year, effectively killing any plans for government censorship. [155]

New Zealand

New Zealand

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for Australia and New Zealand.[100]

Since February 2010 Department of Internal Affairs offers to ISPs voluntary Internet filtering.[156] Participating providers routes suspect destination IP addresses to the Department that blocks desired HTTP requests. Other packets are routed back to correct networks. List of blocked addresses is secret, but it's believed that child pornography is subjected only.

Nigeria

Nigeria

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in October 2009.[1]

In 2008 two journalists were arrested for publishing online articles and photos critical of the government.[157]

Norway

Norway

- Not individually classified by ONI, but included in the regional overview for the Nordic Countries.[132]

Norway's major Internet service providers have a DNS filter which blocks access to sites authorities claim are known to provide child pornography,[158] similar to Denmark's filter. A list claimed to be the Norwegian DNS blacklist was published at Wikileaks in March 2009.[159] The minister of justice, Knut Storberget, sent a letter threatening ISPs with a law compelling them to use the filter should they refuse to do so voluntarily (dated 29 August 2008).[160]

Poland

Poland

- Not individually classified by ONI, but included in the regional overview for Europe.[118]

Internet censorship legislation has been proposed including the creation of a register of blocked web sites, based on a government organ chosen by the government (police, Ministry of Finance, secret police etc.). Project administrative decisions would be made without court intervention and selected addresses would be blocked. The owner of a site would not be informed until the address was blocked, when the decision could be appealed.[citation needed]

Romania

Romania

- Not individually classified by ONI, but included in the regional overview for Europe.[118]

Slovenia

Slovenia

- Not individually classified by ONI.

On 28 January 2010 the Slovenian National Assembly accepted new changes to the law governing gambling which legalized Internet censorship in Slovenia, although just for Internet gambling web sites that run without permission of the Slovenian government. The law makes Internet service providers responsible for accessing those sites and thus requires them to install censorship equipment/systems.

South Africa

South Africa

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for sub-Saharan Africa.[71]

In 2006, the government of South Africa began prohibiting sites hosted in the country from displaying X18 (explicitly sexual) and XXX content (including child pornography and depictions of violent sexual acts); site owners who refuse to comply are punishable under the Film and Publications Act 1996. In 2007 a South African "sex blogger" was arrested arrested. South Africa participates in regional efforts to combat cybercrime. The East African Community (consisting of Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda) and the South African Development Community (consisting of Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) have both enacted plans to standardize cybercrime laws throughout their regions.[71]

Sweden

Sweden

- Not individually classified by ONI, but included in the regional overview for the Nordic Countries.[132]

Sweden's major Internet service providers have a DNS filter which blocks access to sites authorities claim are known to provide child porn, similar to Denmark's filter. A partial sample of the Swedish internet censorship list can be seen at a Finnish site criticizing internet censorship. The Swedish police are responsible for updating this list of forbidden Internet sites. On 6 July, Swedish police said that there is material with child pornography available on torrents linked to from the torrent tracker site Pirate Bay and said it would be included in the list of forbidden Internet sites. This, however, did not happen as the police claimed the illegal material had been removed from the site. Police never specified what the illegal content was on TPB. This came with criticism and accusations that the intended The Pirate Bay's censorship was political in nature.

Uganda

Uganda

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in September 2009.[1]

Though Uganda has made great technological strides in the past five years, the country still faces a number of challenges in obtaining affordable, reliable Internet bandwidth. This, rather than a formal government-sponsored filtering regime, is the major obstacle to Internet access. Just prior to the presidential elections in February 2006, the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) blocked the anti-government Web site RadioKatwe in the only internationally reported case of Internet filtering in Uganda to date.[161]

Ukraine

Ukraine

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in December 2010.[1]

Access to Internet content in Ukraine remains largely unfettered. Ukraine possesses relatively liberal legislation governing the Internet and access to information. The Law on Protection of Public Morals of November 20, 2003 prohibits the production and circulation of pornography; dissemination of products that propagandize war or spread national and religious intolerance; humiliation or insult to an individual or nation on the grounds of nationality, religion, or ignorance; and the propagation of "drug addition, toxicology, alcoholism, smoking and other bad habits."[162]

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in December 2010.[1]

British Telecommunications' ISP passes internet traffic through a service called Cleanfeed which uses data provided by the Internet Watch Foundation to identify pages believed to contain indecent photographs of children.[163][164] When such a page is found, the system creates a 'URL not found page' error rather than deliver the actual page or a warning page. Other ISPs use different systems such as WebMinder [1]. Cleanfeed is a silent content filtering system, which means that internet users cannot ascertain whether they are being regulated by Cleanfeed or facing connection failures. According to a small-sample survey conducted in 2008 by Nikolaos Koumartzis,[165] an MA researcher at London College of Communication, the vast majority of UK based internet users (90.21%) were unaware of the existence of Cleanfeed software. Moreover, 60.87% of the participants stated that they did not trust British Telecommunications and 65.22% of them did not trust IWF to be responsible for a silent censorship system in the UK.

United States

United States

- Not individually classified by ONI, but is included in the regional overview for the United States and Canada.[122]

Most online expression is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, but laws concerning libel, intellectual property, and child pornography still determine if certain content can be legally published online. Internet access by individuals in the US is not subject to technical censorship, but can be penalized by law for violating the rights of others. Content-control software are sometimes used by businesses, libraries, schools, and government offices to limit access to specific types of content.[166]

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

- Listed as no evidence in all four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) by ONI in September 2009.[1]

Because Internet penetration in Zimbabwe is low, it is mainly used for e-mail and the government focuses its efforts to control the Internet to e-mail monitoring and censorship. Though its legal authority to pursue such measures is contested, the government appears to be following through on its wishes to crack down on dissent via e-mail.[167]

See also

- International Freedom of Expression Exchange — monitors Internet censorship worldwide

- Reporters sans frontières (Reporters Without Borders)

References

- Material from the OpenNet Initiative web site is available for reuse under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license (CC BY 3.0)[168] as outlined on the ONI web site.[169]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba "ONI Country Profiles", Research section at the OpenNet Initiative web site, a collaborative partnership of the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto; the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University; and the SecDev Group, Ottawa

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Internet Enemies, Reporters Without Borders, Paris, March 2011

- ^ a b "List of the 13 Internet enemies", Reporters Without Borders, 11 July 2006

- ^ Resolution No 1 of 2009, Ministry of Culture and Information, published in Official Gazette, Issue No.2877, dated 8 January 2009

- ^ "ONI Country Profile: Burma", OpenNet Initiative, 22 December 2010

- ^ Google Public Data: Burma Internet penetration

- ^ a b Internet Enemies, Reporters Without Borders, Paris, March 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g "ONI: Internet Filtering Map" (Flash). Open Net Initiative. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ Burma "Junta tightens media screw", Michael Dobie, BBC News, 28 September 2007

- ^ Thomas Lum and Hannah Fischer (25 January 2010). Human Rights in China: Trends and Policy Implications (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, USA.

- ^ "Minister blames US embargo for low number of Cubans online". Reporters Without Borders. 13 February 2007.

- ^ Timothy Sprinkle (8 November 2006). "Press Freedom Group Tests Cuban Internet Surveillance". World Politics Review..

- ^ "Journalist sentenced to four years in prison as "pre-criminal social danger"". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ^ Lamrani, Salim. Reporters Without Borders' Lies about Cuba, Centre for Research on Globalization, 2 July 2009.

- ^ "Yoani Sánchez: El aumento de la represión coincide con una mayor presencia de los blogueros en las calles (Yoani Sanchez: The increased repression coincides with a greater presence of bloggers on the streets)". Cuba Verdad. 4 January 2010. Template:Es icon

- ^ "Los videos del mitin de repudio contra Reinaldo Escobar (Videos repudiation rally against Reinaldo Escobar)". Penúltimos Días. 21 November 2009. Template:Es icon

- ^ "CPJ Special Report 2006".

- ^ "ONI Country Profile: Iran", OpenNet Initiative, 16 June 2009

- ^ "Authorities urged to halt threats to "cyber-feminists" - Iran". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ^ "Internet "black holes" - Iran". Reporters Without Borders. Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- ^ "Iran blocks access to video-sharing on YouTube". Tehran(AP): USA Today. 5 December 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ^ "Cracking Down on Digital Communication and Political Organizing in Iran", Rebekah Heacock, OpenNet Initiative, 15 June 2009

- ^ ONI Country Profile: Kuwait", OpenNet Initiative, 6 August 2009

- ^ "Kuwait: State of the media", Menassat

- ^ "Middle East and North Africa: Kuwait", Media Sustainability Index, 2006

- ^ "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Kuwait — 2007", Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State, 11 March 2008

- ^ Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research web site

- ^ "VOIP Policy and Regulation: Regional perspective", Professor Ibrahim Kadi, Communications and Information Technology Commission, presented at the regional seminar on Internet Protocol: VOIP, Algiers, Algeria, 12 March 2007

- ^ "Ministry blocks call sites on web", Kuwait Times Online, 13 May 2007

- ^ "Kuwait blocks YouTube", Jamie Etheridge, Kuwait Times, 22 September 2008

- ^ "Kuwaiti MPs call for stricter net censorship", Dylan Bowman, Arabian Business, 29 September 2008

- ^ "ONI Country Profile: North Korea", OpenNet Initiative, 10 May 2007

- ^ "The Internet Black Hole That Is North Korea ", Tom Zeller Jr., New York Times, 23 October 2006

- ^ "Internet Enemies: North Korea", Reporters Without Borders, March 2011

- ^ "ONI Country Profile: Oman", OpenNet Initiative, August 2009

- ^ "ONI Country Profile: Qatar", OpenNet Initiative, 6 August 2009

- ^ a b Internet Filtering in Saudi Arabia in 2004 - An OpenNet Initiative study

- ^ Introduction to Content Filtering, Saudi Arabia Internet Services Unit, of King Abdulaziz City for Science & Technology (KACST), 2006

- ^ Saudi Internet rules (2001), Council of Ministers Resolution, 12 February 2001, Al-Bab gateway: An open door to the Arab world

- ^ "ONI Country Profile: South Korea", OpenNet Initiative, 26 December 2010

- ^ "Tough content rules mute Internet election activity in current contest: Bloggers risk arrest for controversial comments". JoongAng Daily. 17 December 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ Christian Oliver (1 April 2010). "Sinking underlines South Korean view of state as monster". London: Financial Times. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ "Syrian jailed for internet usage". BBC News. 21 June 2004.