Gender disparities in health: Difference between revisions

→Predominantly female-bias: rm sentences too close to source; see talk |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

===Predominantly female-bias=== |

===Predominantly female-bias=== |

||

[[Women]] generally live longer than [[men]] because of both biological and behavioural advantages - on average by six to eight years.<ref name="Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda">{{cite report|author=World Health Organization|date=2009 |title=Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda |publisher=WHO Press|url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563857_eng.pdf |accessdate=18 Mar 2013 }}</ref> However, in certain regions around the world, such as [[South Asia]], [[China]] and [[Sub-Saharan Africa]], these advantages are overridden by gender-based discrimination.<ref name="Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda">{{cite report|author=World Health Organization|date=2009 |title=Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda |publisher=WHO Press |accessdate=18 Mar 2013 }}</ref> |

[[Women]] generally live longer than [[men]] because of both biological and behavioural advantages - on average by six to eight years.<ref name="Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda">{{cite report|author=World Health Organization|date=2009 |title=Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda |publisher=WHO Press|url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563857_eng.pdf |accessdate=18 Mar 2013 }}</ref> However, in certain regions around the world, such as [[South Asia]], [[China]] and [[Sub-Saharan Africa]], these advantages are overridden by gender-based discrimination.<ref name="Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda">{{cite report|author=World Health Organization|date=2009 |title=Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda |publisher=WHO Press |accessdate=18 Mar 2013 }}</ref> Women are often less likely in these regions to receive higher education and be employed in the marketplace because of their gender.<ref name="Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda">{{cite report|author=World Health Organization|date=2009 |title=Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda |publisher=WHO Press |accessdate=18 Mar 2013 }}</ref> As a result, many health outcomes of females, such as [[life expectancy]] at birth, nutritional well-being, and prevalence of [[communicable diseases|communicable]] and [[non-communicable diseases]], are often lower than that of males.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Vlassoff|first=C|title=Gender differences in determinants and consequences of health and illness.|journal=Journal of health, population, and nutrition|date=2007 Mar|volume=25|issue=1|pages=47–61|pmid=17615903}}</ref><ref name="More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing">{{cite journal |last=Sen|first=Amartya|title=More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing|year=1990|journal=New York Review of Books}}</ref> |

||

===Disparities against males=== |

===Disparities against males=== |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

===Cultural norms and practices=== |

===Cultural norms and practices=== |

||

Cultural practices are one of the main causes of why many disparities in health continue to exist |

Cultural practices are one of the main causes of why many disparities in health continue to exist. Some of the examples provided by the [[World Health Organization]] of how cultural norms can result in gender disparities in health include women's inability to travel alone, which can prevent them from receiving the necessary health care that they need.<ref name="World Health Organization: Gender. Women and Health">{{cite web |url=http://www.who.int/gender/genderandhealth/en/index.html |title=Gender, Women, and Health|publisher=WHO |accessdate=17 March 2013}}</ref> Another societal standard is a woman's inability to insist on [[condom]] use by her [[spouse]] or sex partners, leading to a higher risk of contracting [[HIV]].<ref name="World Health Organization: Gender. Women and Health" /> |

||

====Son preference==== |

====Son preference==== |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

health”.<ref name="World Health Report 2001">{{cite report |author= World Health Organization|title=World Health Report 2001|year=2001|url=http://www.who.int/whr/2001/en/whr01_en.pdf|location=Geneva}}</ref> Given the broad social, cultural and economic context in which health systems operate and the impact that factors external to the health system can have on health, health systems are not only “producers of health and health care”, but also “purveyors of a wider set of societal norms and values,” many of which are biased against women<ref name="Trust and the development of health care as a social institution">{{cite journal |last=Gilson|first=L|title=Trust and the development of health care as a social institution|year=2003|journal=Soc Sci Med|volume=56|pages=1453–68}}</ref> |

health”.<ref name="World Health Report 2001">{{cite report |author= World Health Organization|title=World Health Report 2001|year=2001|url=http://www.who.int/whr/2001/en/whr01_en.pdf|location=Geneva}}</ref> Given the broad social, cultural and economic context in which health systems operate and the impact that factors external to the health system can have on health, health systems are not only “producers of health and health care”, but also “purveyors of a wider set of societal norms and values,” many of which are biased against women<ref name="Trust and the development of health care as a social institution">{{cite journal |last=Gilson|first=L|title=Trust and the development of health care as a social institution|year=2003|journal=Soc Sci Med|volume=56|pages=1453–68}}</ref> |

||

In the Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network's Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2007, health systems in many countries were noted to have been unable to deliver adequately on [[gender equity]] in health in particular |

In the Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network's Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2007, health systems in many countries were noted to have been unable to deliver adequately on [[gender equity]] in health in particular.<ref name="Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it">{{cite report |last=Sen|First=Gita|Last2=Östlin|first2=Piroska|title=Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it; Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health|year=2007|publisher=Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network|url=http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/wgekn_final_report_07.pdf}}</ref> |

||

Overall, studies have found evidence that the health care system can promote gender disparities in health through the lack of [[gender equity]] in regarding women as both [[consumers]] (users) and producers (carers) of health care services.<ref name="Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it">{{cite report |last=Sen|First=Gita|Last2=Östlin|first2=Piroska|title=Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it; Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health|year=2007|publisher=Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network|url=http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/wgekn_final_report_07.pdf}}</ref> Health care systems tend to regard women as objects rather than subjects, where services are often provided to women as a means of something else rather on women themselves. In the case of reproductive health services, they are often provided as a form of [[fertility control]] rather than a care for women's well-being.<ref name="Reproductive health and human rights - Integrating medicine, ethics and law">{{cite book |last=Cook|first=R|last2=Dickens|first2=B|last3=Fathalla|first3=M|title=Reproductive health and human rights - Integrating medicine, ethics and law|year=2003|publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> Additionally, although majority of the workforce in health care systems are females, many of the working conditions remain are discriminatory towards women. Many studies have shown that women are often expected to conform to male work models that ignore their special needs, such as childcare or protection from violence.<ref name="Human Resources for Health: a gender analysis">{{cite paper |last=George|first=A|title=Human Resources for Health: a gender analysis|year=2007|publisher=Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network}}</ref> This significantly reduces the ability and efficiency of female [[caregivers]] providing care to female patients.<ref name="Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus">{{cite journal |last=Ogden|first=J|last2=Esim|first2=S|last3=Grown|first3=C|title=Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus|year=2006|journal=Health Policy Plan|volume=21|pages=333–42}}</ref><ref name="World Health Report 2006">{{cite report |author= World Health Organization|title=World Health Report 2006|year=2006|url=http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf|location=Geneva}}</ref> |

Overall, studies have found evidence that the health care system can promote gender disparities in health through the lack of [[gender equity]] in regarding women as both [[consumers]] (users) and producers (carers) of health care services.<ref name="Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it">{{cite report |last=Sen|First=Gita|Last2=Östlin|first2=Piroska|title=Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it; Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health|year=2007|publisher=Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network|url=http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/wgekn_final_report_07.pdf}}</ref> Health care systems tend to regard women as objects rather than subjects, where services are often provided to women as a means of something else rather on women themselves. In the case of reproductive health services, they are often provided as a form of [[fertility control]] rather than a care for women's well-being.<ref name="Reproductive health and human rights - Integrating medicine, ethics and law">{{cite book |last=Cook|first=R|last2=Dickens|first2=B|last3=Fathalla|first3=M|title=Reproductive health and human rights - Integrating medicine, ethics and law|year=2003|publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> Additionally, although majority of the workforce in health care systems are females, many of the working conditions remain are discriminatory towards women. Many studies have shown that women are often expected to conform to male work models that ignore their special needs, such as childcare or protection from violence.<ref name="Human Resources for Health: a gender analysis">{{cite paper |last=George|first=A|title=Human Resources for Health: a gender analysis|year=2007|publisher=Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network}}</ref> This significantly reduces the ability and efficiency of female [[caregivers]] providing care to female patients.<ref name="Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus">{{cite journal |last=Ogden|first=J|last2=Esim|first2=S|last3=Grown|first3=C|title=Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus|year=2006|journal=Health Policy Plan|volume=21|pages=333–42}}</ref><ref name="World Health Report 2006">{{cite report |author= World Health Organization|title=World Health Report 2006|year=2006|url=http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf|location=Geneva}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 22:17, 13 April 2013

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

Health is the general condition of a person's mind and body, usually meaning to be free from illness, injury or pain.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined health as "a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.[2] Identified by the 2012 World Development Report as one of two key human capital endowments, health can influence an individual’s ability to reach their full potential in society.[3] Yet while gender equality has made the most progress in areas like education and labor force participation, health inequality between men and women continues to plague many societies today. While both males and females face health disparities, girls and women experience a majority of health disparities. This comes from the fact that many patriarchal cultural ideologies and practices have structured society in a way whereby women are more vulnerable to abuse and diseases, making them more prone to illnesses and death.[4] Women are also restricted from receiving many direct and indirect opportunities, such as education and pay labor, that can help improve their accessibility to better health care resources.

Definition of health disparity

Health disparity has been defined by the World Health Organization as the differences in health care received that are not only unnecessary and avoidable but are also unfair and unjust.[5] The existence of health disparity implies that there is no health equity. Equity in health refers to the situation whereby everyone has a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential, and if avoidable, no one should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential.[5] Overall, the term "health disparities," or "health inequalities," is widely understood as the differences in health between people with different positions in a socioeconomic hierarchy.[6]

Gender as an axis of difference

Predominantly female-bias

Women generally live longer than men because of both biological and behavioural advantages - on average by six to eight years.[4] However, in certain regions around the world, such as South Asia, China and Sub-Saharan Africa, these advantages are overridden by gender-based discrimination.[4] Women are often less likely in these regions to receive higher education and be employed in the marketplace because of their gender.[4] As a result, many health outcomes of females, such as life expectancy at birth, nutritional well-being, and prevalence of communicable and non-communicable diseases, are often lower than that of males.[7][8]

Disparities against males

While a majority of the health gender disparities are weighted against women, there are some situations where men tend to fare poorer in terms of health outcomes. One such situation is armed conflict, where men are often the immediate victims. A study of conflicts in 13 countries from 1955 to 2002 found that 81% of all violent war deaths were males.[3] Apart from armed conflict, areas with high incidence of violence, such as regions controlled by drug cartels, also see men experiencing higher mortality rates. This stems from social beliefs that link ideals of masculinity with confrontation and aggression.[9] Lastly, changes in economic environments and the weakening of social safety nets have also been linked to higher levels of alcohol consumption and psychological stress among men, leading to a spike in male mortality rates.[10]

Forms of gender disparities

Male-female sex ratio

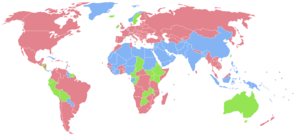

| Countries with more females than males. Countries with the same number of males and females. Countries with more males than females. No data |

At birth, boy outnumber girls everywhere in the world, by roughly 105 or 106 male children for every 100 female children.[8] However, after conception, biology favors women. Considerable research has shown that if men and women receive similar nutrition, medical attention, and general health care, women tend to live longer than men.[11] This is because women, on a whole, are more resistant to diseases and less prone to genetic conditions. However, despite medical and scientific research that shows that when given the same care as males, female tend to have better survival rates than males, the ratio of women to men can still be as low as 0.94, or even lower in developing regions such as South Asia, West Asia, and China. This deviation of the male to female sex ratio has been described by Indian philosopher and economist Amartya Sen as the "missing women" phenomenon.[8] According to the 2012 World Development Report, the number of missing women is estimated to be about 1.5 million women per year, with a majority of the missing women coming from India and China.[3]

Female mortality

In many developing regions, women experience high levels of mortality.[12] Many of these deaths come from maternal mortality and HIV/AIDS. While only 1,900 maternal deaths were recorded in high-income nations in 2008, India and Sub-Saharan Africa saw a combined total of 266,000 deaths from maternal-related reasons. In Somalia and Chad, one in every 14 women will die from causes related to child birth.[3] In addition to maternal mortality, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is also contributing to female mortality. The case is especially true for Sub-Saharan Africa, where women account for 60% of all adult HIV infections.[13]

Health outcomes

Women tend to have poorer health outcomes than men in many different areas, ranging from risk to diseases and illnesses to mortality rates. In the population report that compares the disability-adjusted life years (DALY) of both male and females, the global DALYs lost to females for sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhea and chlamydia is more than 10 times greater than that of males.[14] Moreover, the female DALYs to male DALYs ratio for malnutrition related diseases such as Iron-Deficiency Anemia are often close to 1.5, suggesting that poor nutrition impacts women at a much higher level than men.[14] Additionally, in terms of mental illnesses, women are also two to three times more likely than men to be diagnosed with depression.[15] With regards to suicidal rates, up to 80% of those who committed suicide or attempted suicide in Iran were women.[16]

Access to healthcare

Women tend to have poorer access to health care resources than men. In the case of malaria, women often lack access to malaria treatment during antenatal care as well as access to environments that protect them against mosquitoes. As a result of this, pregnant women who are residing in areas of low or unstable malaria transmission are still at a risk level that is two to three times higher than other men in terms of contracting a severe malaria infection.[17] These disparities in terms of access to healthcare are often compounded by cultural norms and expectations that are being imposed on women.[4]

Causes

Cultural norms and practices

Cultural practices are one of the main causes of why many disparities in health continue to exist. Some of the examples provided by the World Health Organization of how cultural norms can result in gender disparities in health include women's inability to travel alone, which can prevent them from receiving the necessary health care that they need.[18] Another societal standard is a woman's inability to insist on condom use by her spouse or sex partners, leading to a higher risk of contracting HIV.[18]

Son preference

One of the more well-documented cultural ideologies that facilitate gender disparities in health is the preference for sons.[19][20] In India, for instance, the 2001 census recorded only 93 girls per 100 boys – a sharp decline from 1961 when the number of girls was nearly 98.[4] In some parts of India, there are fewer than 80 girls for every 100 boys. Low sex ratios have also been recorded in other Asian countries – most notably China where, according to a survey in 2005, only 84 girls were born for every 100 boys. This was slightly up from 81 during 2001–2004, but much lower than 93 girls per 100 boys as shown among children born in the late 1980s.[4] This increasing number of unborn girls in the late 20th century has been attributed to technological advancements, which made prenatal sex discernment like ultrasound more affordable and accessible to a wider range of people. This allowed parents who prefer to have a son to determine the sex of their unborn child during the early stages of pregnancy. By having early identification of their unborn child's sex, parents could practice sex-selective abortion, where they would abort the unborn child if it was not the preferred sex, which in most cases is when the child was a girl.[3]

Additionally, the culture of son preference also extends beyond birth in the form of preferential treatment of boys.[21] This preferential care can come in many different ways, such as through differential provision of food resources, attention, and medical care. Data from household surveys over the past 20 years has indicated that the female disadvantage has persisted in India and may have even worsened in some other countries such as Nepal and Pakistan.[3]

Female genital mutilation

In certain places, harmful cultural practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) also cause girls and women to face other health risks. Millions of girls and women are estimated to have undergone FGM, which involves partial or total removal of the female external genitalia for nonmedical reasons. It is estimated that 92.5 million girls and women above 10 years of age in Africa are living with the consequences of FGM. Of these, 12.5 million are girls between 10 and 14 years of age. Each year, some three million girls in Africa are subjected to FGM.[18]

Performed by traditional practitioners using unsterile techniques and devices, FGM can have both immediate and late complications.[22][23] These complications include excessive bleeding, urinary infections, wound infection, and in the case of unsterile and reused instruments, hepatitis and HIV.[22] In the long run, scars and keloids can form, which can obstruct and damage the urinary and genital tracts. According to the 2005 UNICEF report on FGM, it is unknown how many girls and women die from the procedure because "few records are kept" and fatalities caused by FGM "are rarely reported as such".[24] Comfort Momoh, a midwife who specializes in FGM, claims that the short-term mortality rate is around 10 percent, due to complications like infection, haemorrhage, and hypovolemic shock.[25] FGM may also complicate pregnancy and place women at a higher risk for obstetrical problems, such as prolonged labor.[22] Moreover, based on a 2006 study conducted on 28,393 women by WHO, neonatal mortality is increasing in women with FGM, where an additional of 10–20 babies are estimated to die per 1,000 deliveries as a result of FGM.[26]

Psychological complications are related to cultural context. Women who undergo FGM might be emotionally affect when they are moving outside their traditional circles and are confronted with a view that mutilation is not the norm.[22] Additionally, it has been argued that FGM is related to the high incidence of AIDS in some parts of Africa, since intercourse with a circumcised female is conducive to an exchange of blood.[27]

Violence and abuse

Many societies in developing nations often function on a patriarchal framework, where women are often viewed as property or socially inferior to men. This unequal social standing has led women to be physically and sexually abused by male violence, both as children and adults. Although children of both sexes suffer from physical maltreatment, sexual abuse, and other forms of exploitation and violence, studies have indicated that girls are far more likely than boys to suffer sexual abuse. In a 2004 study on child abuse, 25.3% of all girls surveyed experienced some form of sexual abuse, a percentage that is 3 times higher that boys (8.7%).[28] This level of risk increases in developing regions as women are frequently placed in emergency and refugee settings as a result of social instability around the region. In conflict and post-conflict situations, sexual violence is increasingly recognized as a tactic of war. It is in those settings where girls are more vulnerable to sexual violence, exploitation and abuse by combatants, security forces, and members of rival communities.[28]

The sexual violence and abuse of young females has both immediate and long-term consequences for the health of women, and contributes significantly to a myriad of health issues in adulthood. Some of these health issues can range from depression, alcohol and drug use and dependence, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide attempts.[29]

Violence against adult women is also a widespread occurrence worldwide with serious public health implications. Violence against women can directly lead to serious injury, disability, or even death. It can also indirectly lead to a variety of health problems such as stress-induced physiological changes, substance use, or lack of fertility control and personal autonomy as often seen in abusive relationships. Abused women have higher rates of unintended pregnancies, abortions, adverse pregnancies and neonatal and infant outcomes, sexually transmitted infections (including HIV), and mental disorders (such as depression, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders and eating disorders) compared to their non-abused peers.[3] Most violence against women is perpetrated by intimate male partners. A WHO study in 11 countries found that between 15% and 71% of women, depending on the country, had experienced physical or sexual violence by a husband or partner in their lifetime, and 4% to 54% had experienced it within the previous year.[30] Partner violence may also be fatal. Studies from Australia, Canada, Israel, South Africa and the United States show that between 40% and 70% of female murders were carried out by intimate partners.[31]

Other forms of violence against women include sexual harassment and abuse by authority figures (such as teachers, police officers or employers), trafficking for forced labour or sex, and traditional practices such as forced child marriages and dowry-related violence. Violence against women is often related to social and gender bias.[32] Another societal standard is a woman's inability to insist on condom use by her spouse or sex partners, leading to a higher risk of contracting HIV.[18] At its most extreme, violence against women can result in female infanticide and violent death. Despite the size of the problem, many women do not report their experience of violence and do not seek help. As a result, violence against women remains a hidden problem with great human and health-care costs.[32]

Poverty

Poverty is another factor that facilitates the continual existence of gender disparities in health.[3] Poverty often works in tandem with cultural norms to indirectly impact women's health. While many communities and households are not opposed to helping women attain better health through education, better nutrition, and financial stability, poverty serves as a form of resistance against gender equity in health for women out of economic necessity. Oftentimes, due to financial constraints, there is usually only sufficient resources to provide for opportunities, like education, that can help one attain better health outcomes. However, cultural norms will often dictate that the male receives these opportunities. This stems from both the societal preference as well as the fact that the potential returns of having the male receive these opportunities is oftentimes much higher than that of a female.[33]

Healthcare system

The World Health Organization defines health systems as “all the activities whose primary purpose is to promote, restore, or maintain health”.[34] Given the broad social, cultural and economic context in which health systems operate and the impact that factors external to the health system can have on health, health systems are not only “producers of health and health care”, but also “purveyors of a wider set of societal norms and values,” many of which are biased against women[35]

In the Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network's Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2007, health systems in many countries were noted to have been unable to deliver adequately on gender equity in health in particular.[36]

Overall, studies have found evidence that the health care system can promote gender disparities in health through the lack of gender equity in regarding women as both consumers (users) and producers (carers) of health care services.[36] Health care systems tend to regard women as objects rather than subjects, where services are often provided to women as a means of something else rather on women themselves. In the case of reproductive health services, they are often provided as a form of fertility control rather than a care for women's well-being.[37] Additionally, although majority of the workforce in health care systems are females, many of the working conditions remain are discriminatory towards women. Many studies have shown that women are often expected to conform to male work models that ignore their special needs, such as childcare or protection from violence.[38] This significantly reduces the ability and efficiency of female caregivers providing care to female patients.[39][40]

Structural gender oppression

Structural gender inequalities in the allocation of resources, such as income, education, health care, nutrition and political voice, are strongly associated with poor health and reduced well-being. Very often, such structural gender discrimination of women in many other areas has an indirect impact on women's health. For example, because women in many developing nations are less likely to be part of the formal labor market, they often lack access to job security and the benefits of social protection, including access to health care. Additionally, within the formal workforce, women often face challenges related to their lower status, where they suffer workplace discrimination and sexual harassment. Studies have shown that this expectation of having to balance the demands of paid work and work at home often give rise to work-related fatigue, infections, mental ill-health and other problems, which results in women faring poorer in health.[41]

Women’s health is also put at a higher level of risk as a result of being confined to certain traditional responsibilities, like cooking and water collection. Being confined to unpaid domestic labor not only reduces women's opportunities to education and formal job employment, both of which can indirectly contribute to better health in the long run, but also potentially put women at risk of health issues. For instance, in developing regions where solid fuels are used for cooking, women are exposed to a higher level of indoor air pollution due to extended periods of cooking and preparing meals for the family. Breathing air tainted by the burning of solid fuels is estimated to be responsible for 641,000 of the 1.3 million deaths of women worldwide each year due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) among women each year.[42]

In some settings, structural gender inequity is associated with particular forms of violence against females – including violence by an intimate partner, sexual violence by acquaintances and strangers, child sexual abuse, forced sexual initiation, and female genital mutilation.[4] Women and girls are also vulnerable to less well-documented forms of abuse or exploitation, such as human trafficking or “honour killings” for perceived transgressions of their social role. These acts are associated with a wide range of health problems in women such as injuries, unwanted pregnancies, abortions, depression, anxiety and eating disorders, substance use, sexually transmitted infections and premature death.[43][44]

Other axes of oppression

Apart from gender discrimination, other axes of oppression also exist in society to further marginalized certain groups of women, especially those who are of minority ethnicity or living in poverty.[4]

Race and ethnicity

Race is a well known axis of oppression, where communities of color tend to suffer more from structural violence. For people of color, race can serve as a factor, in addition to gender, that can further influence one's health negativity.[45] Studies have shown that in both high-income and low-income countries, levels of maternal mortality may be up to three times higher among women of disadvantaged ethnic groups than among white women. In a study on race and mother-death within the USA, the maternal mortality rate for African Americans is close to 4 times higher than that of white women. The trend is similar in South Africa as well, where the maternal mortality rate for black/African women is approximately 10 times greater than that of women of white/European descent - women of color was about 5 times greater.[46]

Socioeconomic status

While there are many commonalities in the health challenges facing women around the world, there are also striking differences due to the varied conditions in which they live. The type of living conditions in which women live is largely associated with of not only their own socioeconomic status, but also that of their nation.[4]

Women in high income countries tend to live longer and are less likely to suffer from ill health than women in low-income countries. At every age, women in high-income countries live longer and are less likely to suffer from ill-health and premature mortality than those in low income countries. Death rates in high-income countries are also very low among children and younger women, where most deaths occur after the age of 60 years. In low-income countries however, the death rates at young ages are higher, with most death occurring among girls, adolescents, and younger adult women. The most striking difference between rich and poor countries is in maternal mortality, where 99% of the more than half a million maternal deaths every year happen in developing countries. The highest burden of the mortality is often concentrated in the poorest and often the institutionally weakest countries, particularly those facing humanitarian crises. Data from 66 developing countries show that child mortality rates among the poorest 20% of the population are almost double those in the top 20%. [47]

Within countries, the health of girls and women is critically affected by social and economic factors as well, where those who are in poverty or of lower socioeconomic status tend to perform poorly in terms of health outcomes. In almost all countries, girls and women living in wealthier households have lower levels of mortality and higher use of health-care services than those living in the poorest households. Such differences are not confined to developing countries but are found in the developed world.[4]

Management

The Fourth World Conference on Women asserts that men and women share the same right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.[48] However, women are disadvantaged due to social, cultural, political and economic factors that directly influence their health and impede their access to health-related information and care.[4] In the 2008 World Health Report, the World Health Organization stressed that strategies to improve women’s health must take full account of the underlying determinants of health, particularly gender inequality. Additionally, specific socioeconomic and cultural barriers that hamper women in protecting and improving their health must also be addressed. [49]

Gender mainstreaming

Gender mainstreaming was established as a major global strategy for the promotion of gender equality in the Beijing Platform for Action from the Fourth United Nations World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995.[50] Gender mainstreaming was defined by the United Nations Economic and Social Council in 1997 as follows: “Mainstreaming a gender perspective is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes, in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making women’s as well as men’s concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres so that women and men benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated. The ultimate aim is to achieve gender equality.”[50]

Over the past few years, "gender mainstreaming" has become a preferred approach for achieving greater health parity between men and women. It stems from recognition that while technical strategies are necessary, they are not sufficient in alleviating gender disparities in health unless the gender discrimination, bias and inequality that permeate the organizational structures of governments and organizations – including health systems - are being challenged and addressed.[4] The gender mainstreaming approach was a response to this realisation that gender concerns must be dealt with in every aspect of policy development and programming, through systematic gender analyses and the implementation of actions that address the balance of power and the distribution of resources between women and men.[51] In order to address gender health disparities, gender mainstreaming in health employs a dual focus. First, it seeks to identify and address gender-based differences and inequalities in all health initiatives; and two, it works to implement implement initiatives that address women’s specific health needs that are a result either of biological differences between women and men (e.g. maternal health) or of gender-based discrimination in society (e.g. gender-based violence; poor access to health services).[52]

Sweden’s new public health policy, which came into force in 2003, has been identified as an key example of mainstreaming gender in health policies. According to the World Health Organization, Sweden’s public health policy was designed to address not only the broader social determinants of health, but also the way in which gender is woven into the public health strategy.[52][53][54] The policy document specifically highlights its commitment to a gender perspective and to reducing gender-based inequalities in health.[55]

Female Empowerment

The United Nations has identified the enhancement of women's involvement as way to achieve gender equality in the realm of education, work, and health.[56] This is because women play critical roles as caregivers, both formally and informally, in the household and community. Within the United States, an estimated 66% of all caregivers are female, with one-third of all female caregivers taking care of two or more people[57] According to the World Health Organization, it is important that approaches and frameworks that are being implemented to address gender disparities in health acknowledge this fact.[4] A meta-analysis of 40 different women's empowerment projects found that increased female participation have led to a broad range of quality of life improvements. These improvements include increases in women's advocacy demands and organization strengths, for-women policy and governmental changes, and improved economic conditions for lower class women.[58]

In Nepal, a community-based participatory intervention to identify local birthing problems and formulating strategies has been shown to be effective in reducing both neonatal and maternal mortality in a rural population.[59] Community-based programs in Malaysia and Sri Lanka that had well-trained midwives as front-line health workers also produced rapid declines in maternal mortality.[60]

References

- ^ "Health - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam Webster. Retrieved 07 Apr 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ World Health Organization (2006). Constitution of the World Health Organization - Basic Documents, Forty-fifth edition (PDF) (Report).

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|Accessed=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h The World Bank (2012). World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development (Report). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n World Health Organization (2009). Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda (PDF) (Report). WHO Press. Retrieved 18 Mar 2013. Cite error: The named reference "Women & Health: Today's Evidence, Tomorrow's Agenda" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Whitehead, M (1990). The Concepts and Principles of Equity in Health (PDF) (Report). Copenhagen:

WHO, Reg. Off. Eur. p. 29. Retrieved 18 Mar 2013.

{{cite report}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 12 (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103instead. - ^ Vlassoff, C (2007 Mar). "Gender differences in determinants and consequences of health and illness". Journal of health, population, and nutrition. 25 (1): 47–61. PMID 17615903.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Sen, Amartya (1990). "More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing". New York Review of Books.

- ^ Márquez, Patricia (1999). The Street Is My Home: Youth and Violence in Caracas. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- ^ Brainerd, Elizabeth; Cutler, David (2005). "Autopsy on an Empire: Understanding Mortality in Russia and the Former Soviet Union". Ann Arbor, MI: William Davidson Institute.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dennerstein, L; Feldman, S; Murdaugh, C; Rossouw, J; Tennstedt, S (1977). 1997 World Congress of Gerontology: Ageing Beyond 2000 : One World One Future. Adelaide: International Association of Gerontology.

- ^ Prata, Ndola (1 March 2010). "Maternal mortality in developing countries: challenges in scaling-up priority interventions". Women's Health. 6 (2): 311–327. doi:10.2217/WHE.10.8.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ UNAIDS (2010). "Women, Girls, and HIV" UNAIDS Factsheet 10 (Report). Geneva: UNAIDS.

- ^ a b Rachel Snow (2007). Population Studies Center Research Report 07-628: Sex, Gender and Vulnerability (PDF) (Report). Population Studies Center, University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research.

- ^ Usten, T; Ayuso-Mateos, J; Chatterji, S; Mathers, C; Murray, C (2004). "Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000". Br J Psychiatry. 184: 386–92.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.309, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.309instead. - ^ WHO/UNICEF (2003). The Africa Malaria Report 2003 (Report). Geneva: WHO/UNICEF.

- ^ a b c d "Gender, Women, and Health". WHO. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Edlund, Lena (1 December 1999). "Son Preference, Sex Ratios, and Marriage Patterns". Journal of Political Economy. 107 (6, Part 1): 1275. doi:10.1086/250097.

- ^ Das Gupta, Monica (1 December 2003). "Why is Son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? a cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea". Journal of Development Studies. 40 (2): 153–187. doi:10.1080/00220380412331293807.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Arnold, Fred (1 November 1998). "Son Preference, the Family-building Process and Child Mortality in India". Population Studies. 52 (3): 301–315. doi:10.1080/0032472031000150486.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Abdulcadir, J (6 January 2011). "Care of women with female genital mutilation/cutting". Swiss Medical Weekly. doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13137.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kelly, Elizabeth (1 October 2005). "Female genital mutilation". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 17 (5): 490–494. doi:10.1097/01.gco.0000183528.18728.57.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ UNICEF (2005). Changing a Harmful Social Convention: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (Report). Florence, Italy: Innocenti Digest/UNICEF.

- ^ Momoh, Comfort (2005). Female Genital Mutilation. Abingdon, Oxon: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.

- ^ "Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries". The Lancet. 367 (9525): 1835–1841. 1 June 2006. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3.

- ^ LINKE, U. (17 January 1986). "AIDS in Africa". Science. 231 (4735): 203–203. doi:10.1126/science.231.4735.203-b.

- ^ a b Ezzati, M; Lopez, A; Rodgers, A; Murray, C (2004). "Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors". Geneva: World Health Organization.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Garcia-Moreno, C; Reis, C (2005). "Overview on women's health in crises" (PDF). Health in emergencies (20). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8instead. - ^ Krug, E (2002). World report on violence and health (Report). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- ^ a b "Violence and injuries to/against women". WHO. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1086/378571, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1086/378571instead. - ^ World Health Organization (2001). World Health Report 2001 (PDF) (Report). Geneva.

- ^ a b Sen (2007). Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it; Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (PDF) (Report). Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network.

{{cite report}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help); Unknown parameter|First=ignored (|first=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Last2=ignored (|last2=suggested) (help) - ^ Cook, R; Dickens, B; Fathalla, M (2003). Reproductive health and human rights - Integrating medicine, ethics and law. Oxford University Press.

- ^ George, A (2007). "Human Resources for Health: a gender analysis". Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ogden, J; Esim, S; Grown, C (2006). "Expanding the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: bringing carers into focus". Health Policy Plan. 21: 333–42.

- ^ World Health Organization (2006). World Health Report 2006 (PDF) (Report). Geneva.

- ^ Wamala, S; Lynch, J (2002). Gender and socioeconomic inequalities in health. Lund, Studentlitteratur.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The global burden of disease: 2004 update (PDF) (Report). Geneva. 2008.

{{cite report}}: Text "author: World Health Organization" ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S1049-3867(01)00085-8, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S1049-3867(01)00085-8instead. - ^ Farmer, Paul (2005). Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War On the Poor. California: University of California Press.

- ^ Seager, Roni (2009). The Penguin Atlas of Women in the World, 4th Edition. New York, New York: The Penguin Group.

- ^ World Health Organization (2009). World health statistics 2009 (Report). Geneva.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ United Nations (1996). Report of the Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing 4–15 September 1995 (PDF) (Report). New York: United Nations.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help) - ^ World Health Organization (2008). The World Health Report 2008, Primary Health Care: Now more than ever (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization.

{{cite report}}: Text "Geneva" ignored (help) - ^ a b United Nations (2002). Gender Mainstreaming: An Overview (PDF) (Report). United Nations.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|Location=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ^ Ravindran, T.K.S. (1 April 2008). "Gender mainstreaming in health: looking back, looking forward". Global Public Health. 3 (sup1): 121–142. doi:10.1080/17441690801900761.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Ravindran, TKS; Kelkar-Khambete, A (2007). Women’s health policies and programmes and gender mainstreaming in health policies, programmes and within the health sector institutions. Background paper prepared for the Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2007 (PDF) (Report).

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help)). Cite error: The named reference "Women’s health policies and programmes and gender mainstreaming in health policies, programmes and within the health sector institutions." was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Ostlin, P; Diderichsen, F (2003). "Equity-oriented national strategy for public health in Sweden: A case study" (PDF). European Centre for Health Policy. Retrieved 09 April 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Linell, A. (22 January 2013). "The Swedish National Public Health Policy Report 2010". Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 41 (10 Suppl): 3–56. doi:10.1177/1403494812466989.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Agren, G (2003). Sweden’s new public health policy: National public health objectives for Sweden (Report). Stockholm.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ Division for Advancement of Women, United Nations (2005). Enhancing Participation of Women in Development through an Enabling Environment for Achieving Gender Equality and the Advancement of Women, Expert Group Meeting, Bangkok, Thailand, 8 - 11 November 2005 (Report).

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help) - ^ National Alliance for Caregiving in collaboration with AARP (2009). Caregiving in the U.S. 2009 (PDF) (Report).

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help) - ^ Wallerstein, N (2006). What is the evidence on effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? Health Evidence Network Report (PDF) (Report). Copenhagen: Europe, World Health Organisation.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|accessed=ignored (help) - ^ Manandhar, Dharma S (1 September 2004). "Effect of a participatory intervention with women's groups on birth outcomes in Nepal: cluster-randomised controlled trial". The Lancet. 364 (9438): 970–979. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17021-9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pathmanathan, Indra; Liljestrand, Jerker; Martins first3=Jo. M.; Rajapaksa, Lalini C.; Lissner, Craig; de Silva, Amala; Selvaraju, Swarna; Singh first8=PrabhaJoginder (2003). "Investing in maternal health : learning from Malaysia and Sri Lanka". The World Bank, Human Development Network. Health, Nutrition, and Population Series.

{{cite journal}}: Missing pipe in:|last3=(help); Missing pipe in:|last8=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)