William Hayden English: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) m [458]Add: issue, doi. Tweak: url. | Quadell |

m minor c/e |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==Family and early career== |

==Family and early career== |

||

William Hayden English was born August 27, 1822 in [[Lexington, Indiana]], the only son of Elisha Gale English and his wife, Mahala (Eastin) English.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} His parents, both [[Kentucky]] natives, had moved to Indiana in 1818, and Elisha English quickly became involved in local politics as a [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrat]], serving in the state legislature as well as building a prominent business career.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=8}} William English was educated in the local public schools, later attending [[Hanover College]].{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} He left college after three years and began to read law. In 1840, English was admitted to the [[Bar (law)|bar]] at the age of eighteen and soon built a practice in his native [[Scott County, Indiana|Scott County]].{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} He started early in politics |

William Hayden English was born August 27, 1822, in [[Lexington, Indiana]], the only son of Elisha Gale English and his wife, Mahala (Eastin) English.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} His parents, both [[Kentucky]] natives, had moved to Indiana in 1818, and Elisha English quickly became involved in local politics as a [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrat]], serving in the state legislature as well as building a prominent business career.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=8}} William English was educated in the local public schools, later attending [[Hanover College]].{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} He left college after three years and began to read law. In 1840, English was admitted to the [[Bar (law)|bar]] at the age of eighteen and soon built a practice in his native [[Scott County, Indiana|Scott County]].{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} He started early in politics as well, attending the state Democratic convention that same year and giving speeches on behalf of the Democratic presidential candidate, [[Martin Van Buren]].{{sfn|Kennedy et al|p=220}} |

||

By the end of 1842, young English came under the mentorship of [[Lieutenant Governor of Indiana|Lieutenant Governor]] [[Jesse D. Bright]], who helped him win appointments to a variety of local offices.{{sfn|Bright|pp=370–392}} The following year, English was chosen as clerk of the [[Indiana House of Representatives]].{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} In 1844, he again worked the campaign trail, this time in service of presidential candidate [[James K. Polk]].{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} As a reward, English was given a [[Spoils system|patronage]] appointment as a clerk in the federal [[United States Department of the Treasury|Treasury Department]] in [[Washington, D.C.]]{{sfn|Kennedy et al|p=220}} He held |

By the end of 1842, young English came under the mentorship of [[Lieutenant Governor of Indiana|Lieutenant Governor]] [[Jesse D. Bright]], who helped him win appointments to a variety of local offices.{{sfn|Bright|pp=370–392}} The following year, English was chosen as clerk of the [[Indiana House of Representatives]].{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} In 1844, he again worked the campaign trail, this time in the service of presidential candidate [[James K. Polk]].{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} As a reward, English was given a [[Spoils system|patronage]] appointment as a clerk in the federal [[United States Department of the Treasury|Treasury Department]] in [[Washington, D.C.]]{{sfn|Kennedy et al|p=220}} He held this position for four years, during which time he met Emma Mardulia Jackson, whom he married in November 1847.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=17}} They would have two children: [[William Eastin English|William E.]] and Rosalind.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=17}} |

||

English attended the [[1848 Democratic National Convention]] in [[Baltimore]], where he supported the eventual nominee, [[Lewis Cass]]. With the election of the [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig Party]]'s candidate, [[Zachary Taylor]], to the presidency, a Whig party member replaced English at the Treasury Department, but he found a job as clerk to the [[United States Senate]]'s [[United States Senate Committee on Claims|Claims Committee]], serving until 1850.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} Later that year, he returned to Indiana to work as secretary to the Indiana [[constitutional convention (political meeting)|Constitutional Convention]].{{sfn|Kennedy et al|p=220}} Democrats were in the majority at the convention, and their views were included in the new law, including increasing the number of elective offices, guaranteeing a [[homestead exemption]], and restricting voting rights to white men.{{sfn|Van Bolt|pp=136–139}} The voters approved the new [[Constitution of Indiana#Constitution of 1851|Constitution of 1851]] by a large majority.{{sfn|Van Bolt|p=141}} |

English attended the [[1848 Democratic National Convention]] in [[Baltimore]], where he supported the eventual nominee, [[Lewis Cass]]. With the election of the [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig Party]]'s candidate, [[Zachary Taylor]], to the presidency, a Whig party member replaced English at the Treasury Department, but he found a job as clerk to the [[United States Senate]]'s [[United States Senate Committee on Claims|Claims Committee]], serving until 1850.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=9}} Later that year, he returned to Indiana to work as secretary to the Indiana [[constitutional convention (political meeting)|Constitutional Convention]].{{sfn|Kennedy et al|p=220}} Democrats were in the majority at the convention, and their views were included in the new law, including increasing the number of elective offices, guaranteeing a [[homestead exemption]], and restricting voting rights to white men.{{sfn|Van Bolt|pp=136–139}} The voters approved the new [[Constitution of Indiana#Constitution of 1851|Constitution of 1851]] by a large majority.{{sfn|Van Bolt|p=141}} |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

English declined to run for reelection in 1860, but did give several speeches advocating compromise and moderation in the growing North-South divide. After [[Abraham Lincoln]]'s election that year, English urged Southerners not to secede.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=12}} When the Southern states did secede and the [[American Civil War|Civil War]] began, Governor [[Oliver P. Morton]] offered English command of a regiment, but he declined it, having no military knowledge or interests.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=13}} He did, however, support Morton's (and Lincoln's) war policies and considered himself a [[War Democrat]]. English loaned money to the state government to cover the expenses of outfitting the troops and served as [[provost marshal]] for the 2nd congressional district.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=13}} |

English declined to run for reelection in 1860, but did give several speeches advocating compromise and moderation in the growing North-South divide. After [[Abraham Lincoln]]'s election that year, English urged Southerners not to secede.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=12}} When the Southern states did secede and the [[American Civil War|Civil War]] began, Governor [[Oliver P. Morton]] offered English command of a regiment, but he declined it, having no military knowledge or interests.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=13}} He did, however, support Morton's (and Lincoln's) war policies and considered himself a [[War Democrat]]. English loaned money to the state government to cover the expenses of outfitting the troops and served as [[provost marshal]] for the 2nd congressional district.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=13}} |

||

After retiring from Congress, English spent a year at his home in Scott County before relocating to [[Indianapolis]], the state capital.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=13}} English and ten associates (including [[James Lanier]]) organized the [[First National Bank of Indianapolis]] in 1863, the first bank in that city chartered under the new [[National Bank Act]].{{sfn|Zeigler|p=292}} He remained president of that bank until 1877, including the difficult period during the [[Panic of 1873]], when many other banks folded.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=13}} English's business interests included other industries as well. He became the controlling shareholder of the [[Indianapolis Street Railway Company]], remaining in charge of that company until 1876, when he sold his shares.{{sfn|Nicholas|p=545}} Having sold |

After retiring from Congress, English spent a year at his home in Scott County before relocating to [[Indianapolis]], the state capital.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=13}} English and ten associates (including [[James Lanier]]) organized the [[First National Bank of Indianapolis]] in 1863, the first bank in that city chartered under the new [[National Bank Act]].{{sfn|Zeigler|p=292}} He remained president of that bank until 1877, including the difficult period during the [[Panic of 1873]], when many other banks folded.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=13}} English's business interests included other industries as well. He became the controlling shareholder of the [[Indianapolis Street Railway Company]], remaining in charge of that company until 1876, when he sold his shares.{{sfn|Nicholas|p=545}} Having also sold his shares of the bank by 1877, English turned most of his investment capital to real estate. By 1875, he had already ordered construction of seventy-five houses along what is now English Avenue.{{sfn|Draegart 1954|p=114}} By the time he died in 1896, he owned 448 pieces of property, most of them in Indianapolis.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=14}} |

||

In 1880, English constructed English's Opera House, which was quickly considered Indianapolis's finest.{{sfn|Nicholas|p=545}} The building was modeled after the [[Pike's Opera House|Grand Opera House]] in New York and seated 2000 people.{{sfn|Draegart 1956a|pp=25–26}} It opened on September 27, 1880 with a performance of ''[[Hamlet (opera)|Hamlet]]'' starring [[Lawrence Barrett]].{{sfn|Draegart 1956a|pp=25–26}} By that time, English was involved in politics once more, and he turned over management of the Opera House to his son, William Eastin English, who was interested in the theater (and had just married an actress, Annie Fox).{{sfn|Draegart 1956a|pp=25–26}} English senior later added a hotel to the Opera House |

In 1880, English constructed English's Opera House, which was quickly considered Indianapolis's finest.{{sfn|Nicholas|p=545}} The building was modeled after the [[Pike's Opera House|Grand Opera House]] in New York and seated 2000 people.{{sfn|Draegart 1956a|pp=25–26}} It opened on September 27, 1880, with a performance of ''[[Hamlet (opera)|Hamlet]]'' starring [[Lawrence Barrett]].{{sfn|Draegart 1956a|pp=25–26}} By that time, English was involved in politics once more, and he turned over management of the Opera House to his son, William Eastin English, who was interested in the theater (and had just married an actress, Annie Fox).{{sfn|Draegart 1956a|pp=25–26}} English senior later added a hotel to the Opera House, and both operated until 1948.{{sfn|Worth|p=547}} |

||

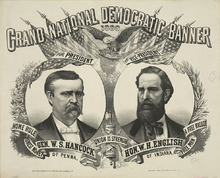

==Vice-presidential candidate== |

==Vice-presidential candidate== |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

After leaving the House of Representatives, English had remained in touch with local politics, even serving as chairman of the Indiana Democratic Party. His son had been elected to the state House in 1879, and the elder English was still consulted on political matters, but had not sought elected office since 1858.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=14}} It was in that spirit that English attended the [[1880 Democratic National Convention]] in [[Cincinnati]] as a member of the Indiana delegation. English entered the convention favoring [[Thomas F. Bayard]] of [[Delaware]], whom he admired for his support of the gold standard.{{sfn|Clancy|pp=64–65}} The first ballot was inconclusive, with Bayard in second place and one delegate voting for English.{{sfn|Clancy|pp=137–138}} Major General [[Winfield Scott Hancock]] of [[Pennsylvania]] led the voting, and on the second ballot was nominated for President.{{sfn|Jordan|pp=274–280}} The Indiana delegation held back their votes from Hancock until the crucial moment, and as a reward, English was selected for the vice-presidential nomination.{{sfn|Jordan|p=281}} The nomination was unanimous. He was not expected to add much to the ticket outside of Indiana, but the party leaders thought his popularity in that [[swing state]] would help Hancock against [[James A. Garfield]] and [[Chester A. Arthur]], the Republican nominees.{{sfn|Jordan|p=281}} The Republicans believed that the real reason for English's nomination was his willingness to use his personal fortune to finance the campaign, as Democratic campaign coffers were low.{{sfn|Philipp|pp=43–44}} English gave a brief speech accepting the nomination, then replied more formally in a letter a month later. In that letter, English called the disputes of the Civil War settled, and promised a "sound currency, of honest money", the restriction of [[Chinese immigration to the United States|Chinese immigration]], and a "rigid economy in public expenditure".{{sfn|Proceedings|p=168}} He characterized the election as one between {{blockquote|the people endeavoring to regain the political power which rightfully belongs to them, and to restore the pure, simple, economical, constitutional government of our fathers on the one side, and a hundred thousand federal office-holders and their backers, pampered with place and power, and determined to retain them at all hazards, on the other.{{sfn|Proceedings|p=167}}}} |

After leaving the House of Representatives, English had remained in touch with local politics, even serving as chairman of the Indiana Democratic Party. His son had been elected to the state House in 1879, and the elder English was still consulted on political matters, but had not sought elected office since 1858.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=14}} It was in that spirit that English attended the [[1880 Democratic National Convention]] in [[Cincinnati]] as a member of the Indiana delegation. English entered the convention favoring [[Thomas F. Bayard]] of [[Delaware]], whom he admired for his support of the gold standard.{{sfn|Clancy|pp=64–65}} The first ballot was inconclusive, with Bayard in second place and one delegate voting for English.{{sfn|Clancy|pp=137–138}} Major General [[Winfield Scott Hancock]] of [[Pennsylvania]] led the voting, and on the second ballot was nominated for President.{{sfn|Jordan|pp=274–280}} The Indiana delegation held back their votes from Hancock until the crucial moment, and as a reward, English was selected for the vice-presidential nomination.{{sfn|Jordan|p=281}} The nomination was unanimous. He was not expected to add much to the ticket outside of Indiana, but the party leaders thought his popularity in that [[swing state]] would help Hancock against [[James A. Garfield]] and [[Chester A. Arthur]], the Republican nominees.{{sfn|Jordan|p=281}} The Republicans believed that the real reason for English's nomination was his willingness to use his personal fortune to finance the campaign, as Democratic campaign coffers were low.{{sfn|Philipp|pp=43–44}} English gave a brief speech accepting the nomination, then replied more formally in a letter a month later. In that letter, English called the disputes of the Civil War settled, and promised a "sound currency, of honest money", the restriction of [[Chinese immigration to the United States|Chinese immigration]], and a "rigid economy in public expenditure".{{sfn|Proceedings|p=168}} He characterized the election as one between {{blockquote|the people endeavoring to regain the political power which rightfully belongs to them, and to restore the pure, simple, economical, constitutional government of our fathers on the one side, and a hundred thousand federal office-holders and their backers, pampered with place and power, and determined to retain them at all hazards, on the other.{{sfn|Proceedings|p=167}}}} |

||

Hancock and the Democrats expected to carry the [[Solid South]], which, with the disenfranchisement of blacks following the end of [[Reconstruction Era|Reconstruction]], was dominated electorally by white Democrats.{{sfn|Clancy|p=250}} In addition to the South, the ticket needed to add a few of the Midwestern states to their total to win the election; national elections in that era were largely decided by closely divided states there.{{sfn|Jensen|pp=xv–xvi}} The practical differences between the parties were few, and the Republicans were reluctant to attack Hancock personally because of his heroic reputation.{{sfn|Jordan|pp=292–296}} The one policy difference the Republicans were able to exploit was a statement in the Democratic platform endorsing "a [[Tariffs in United States history|tariff]] for revenue only".{{sfn|Jordan|p=297}} Garfield's campaign used this statement to paint the Democrats as unsympathetic to the plight of industrial laborers, who benefited from the high protective tariff then in place. The tariff issue cut Democratic support in industrialized Northern states, which were essential in establishing a Democratic majority.{{sfn|Jordan|pp=297–301}} |

Hancock and the Democrats expected to carry the [[Solid South]], which, with the disenfranchisement of blacks following the end of [[Reconstruction Era|Reconstruction]], was dominated electorally by white Democrats.{{sfn|Clancy|p=250}} In addition to the South, the ticket needed to add a few of the Midwestern states to their total to win the election; national elections in that era were largely decided by closely divided states there.{{sfn|Jensen|pp=xv–xvi}} The practical differences between the parties were few, and the Republicans were reluctant to attack Hancock personally because of his heroic reputation.{{sfn|Jordan|pp=292–296}} The one policy difference the Republicans were able to exploit was a statement in the Democratic platform endorsing "a [[Tariffs in United States history|tariff]] for revenue only".{{sfn|Jordan|p=297}} Garfield's campaign used this statement to paint the Democrats as unsympathetic to the plight of industrial laborers, who benefited from the high protective tariff then in place. The tariff issue cut Democratic support in industrialized Northern states, which were essential in establishing a Democratic majority.{{sfn|Jordan|pp=297–301}} |

||

The October state elections in Ohio and Indiana resulted in Republican victories there, discouraging Democrats about the federal election to come the following month.{{sfn|Jordan|pp=297–301}} There was even some talk among party leaders of dropping English from the ticket, but English convinced them that the October losses owed more to local issues, and that the Democratic ticket could still carry Indiana, if not Ohio, in November.{{sfn|Jordan|pp=297–301}} In the end, English was proved wrong: the Democrats and Hancock failed to carry any of the Midwestern states they had targeted, including Indiana. Hancock and English lost the popular vote by just 39,213. The electoral vote, however, had a much larger spread: Garfield-Arthur 214 and Hancock-English 155.{{sfn|Jordan|p=306}} |

|||

==Post-election career== |

==Post-election career== |

||

English resumed his business career after the election. He also became more interested in local history, joining a reunion of the survivors of the 1850 state constitutional convention, which met at his opera house in 1885.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=14}} He became the president of the [[Indiana Historical Society]] and wrote two volumes, which were published at his death: ''Conquest of the Country [[Northwest Territory|Northwest of the River Ohio]], 1778–1783''; and ''Life of General [[George Rogers Clark]]''.{{sfn|Draegart 1956b|pp=352–356}} He served on the Indianapolis Monument Commission in 1893, and helped to plan and finance the [[Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument (Indianapolis)|Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument]].{{sfn|Nicholas|p=545}} |

English resumed his business career after the election. He also became more interested in local history, joining a reunion of the survivors of the 1850 state constitutional convention, which met at his opera house in 1885.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=14}} He became the president of the [[Indiana Historical Society]] and wrote two volumes, which were published at his death: ''Conquest of the Country [[Northwest Territory|Northwest of the River Ohio]], 1778–1783''; and ''Life of General [[George Rogers Clark]]''.{{sfn|Draegart 1956b|pp=352–356}} He served on the Indianapolis Monument Commission in 1893, and helped to plan and finance the [[Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument (Indianapolis)|Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument]] there.{{sfn|Nicholas|p=545}} |

||

He died at his home in Indianapolis on February 7, 1896. English was interred in [[Crown Hill Cemetery]] with his wife, who had died in 1877. Although many of the buildings he constructed have been demolished, [[English, Indiana]], the county seat of [[Crawford County, Indiana|Crawford County]], is named after him, as is English Street in Indianapolis.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=18}} Identical statues of English stand in front of the Scott County Courthouse in [[Scottsburg, Indiana]] and at the Crawford County Fairgrounds in English.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=18}} His son William served in Congress from 1884 to 1885. His grandson, [[William English Walling]], the son of his daughter Rosalind, was a co-founder of the [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]].{{sfn|Craig|p=352}} An extensive collection of English's personal and family papers is housed at the [[Indiana Historical Society]] in Indianapolis, where it is open for research. |

He died at his home in Indianapolis on February 7, 1896. English was interred in [[Crown Hill Cemetery]] with his wife, who had died in 1877. Although many of the buildings he constructed have been demolished, [[English, Indiana]], the county seat of [[Crawford County, Indiana|Crawford County]], is named after him, as is English Street in Indianapolis.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=18}} Identical statues of English stand in front of the Scott County Courthouse in [[Scottsburg, Indiana]], and at the Crawford County Fairgrounds in English.{{sfn|Commemorative Biography|p=18}} His son William served in Congress from 1884 to 1885. His grandson, [[William English Walling]], the son of his daughter Rosalind, was a co-founder of the [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]].{{sfn|Craig|p=352}} An extensive collection of English's personal and family papers is housed at the [[Indiana Historical Society]] in Indianapolis, where it is open for research. |

||

== Notes == |

== Notes == |

||

Revision as of 17:54, 18 December 2013

William Hayden English | |

|---|---|

William Hayden English, c. 1860 | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Indiana's 2nd district | |

| In office March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | Cyrus L. Dunham |

| Succeeded by | James A. Cravens |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 27, 1822 Lexington, Indiana, US |

| Died | February 7, 1896 (aged 73) Indianapolis, Indiana, US |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Emma Mardulia Jackson |

| Children | William E., Rosalind |

| Profession | Politician, lawyer |

William Hayden English (August 27, 1822 – February 7, 1896) was an American congressman from Indiana and the Democratic nominee for vice president in 1880. English entered politics at a young age, becoming a part of Jesse D. Bright's faction of the Indiana Democratic Party. After a few years in the federal bureaucracy in Washington, he returned to Indiana and participated in the state constitutional convention of 1850. He was elected to the state House of Representatives and served as its speaker at the age of twenty-nine. English then represented Indiana in the federal House of Representatives for four terms in the 1850s, working most notably to achieve a compromise on the admission of Kansas as a state.

English retired from the House in 1860, but remained involved in party affairs. He was the Democratic nominee for Vice President in 1880. English and his presidential running mate, Winfield Scott Hancock, lost narrowly to their Republican opponents, James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. In addition to his political career, English was an author and businessman, becoming one of the wealthiest men in Indiana.

Family and early career

William Hayden English was born August 27, 1822, in Lexington, Indiana, the only son of Elisha Gale English and his wife, Mahala (Eastin) English.[1] His parents, both Kentucky natives, had moved to Indiana in 1818, and Elisha English quickly became involved in local politics as a Democrat, serving in the state legislature as well as building a prominent business career.[2] William English was educated in the local public schools, later attending Hanover College.[1] He left college after three years and began to read law. In 1840, English was admitted to the bar at the age of eighteen and soon built a practice in his native Scott County.[1] He started early in politics as well, attending the state Democratic convention that same year and giving speeches on behalf of the Democratic presidential candidate, Martin Van Buren.[3]

By the end of 1842, young English came under the mentorship of Lieutenant Governor Jesse D. Bright, who helped him win appointments to a variety of local offices.[4] The following year, English was chosen as clerk of the Indiana House of Representatives.[1] In 1844, he again worked the campaign trail, this time in the service of presidential candidate James K. Polk.[1] As a reward, English was given a patronage appointment as a clerk in the federal Treasury Department in Washington, D.C.[3] He held this position for four years, during which time he met Emma Mardulia Jackson, whom he married in November 1847.[5] They would have two children: William E. and Rosalind.[5]

English attended the 1848 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore, where he supported the eventual nominee, Lewis Cass. With the election of the Whig Party's candidate, Zachary Taylor, to the presidency, a Whig party member replaced English at the Treasury Department, but he found a job as clerk to the United States Senate's Claims Committee, serving until 1850.[1] Later that year, he returned to Indiana to work as secretary to the Indiana Constitutional Convention.[3] Democrats were in the majority at the convention, and their views were included in the new law, including increasing the number of elective offices, guaranteeing a homestead exemption, and restricting voting rights to white men.[6] The voters approved the new Constitution of 1851 by a large majority.[7]

In August 1851, English won his first election to the state House of Representatives.[1] As it was the first meeting of the legislature under the 1851 constitution, English's knowledge of the new basic law was useful and, at the age of twenty-nine, he was elected speaker.[3] At Bright's direction, English worked for the election of Graham N. Fitch to the federal Senate, but was unsuccessful as the legislature chose John Pettit instead.[a][8] The office of Speaker allowed English's reputation to grow around the state; in 1852, the Democrats chose him as their nominee for the federal House of Representatives from the 2nd district.[9] He was elected that October and joined the 33rd Congress when it convened in Washington in March 1853.[9]

Congress

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The House of Representatives convened for the 33rd Congress in December 1853. At that time, the simmering disagreement between the free and slave states heated up with the introduction of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. The bill, introduced by Illinois Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, opened the Kansas and Nebraska territories to slavery, an implicit repeal of the Missouri Compromise of 1820.[10] Intended to quiet national agitation over slavery by shifting the decision to local settlers, Douglas's proposal instead inflamed anti-slavery sentiment in the North by allowing the possibility of slavery's expansion to territories held as free soil for three decades.[10] English, a member of the Committee on Territories, thought the bill was unnecessary and disagreed with its timing; when the committee approved the bill, English wrote a minority report to that effect.[9] He was not altogether opposed to the principle of popular sovereignty, however, believing that "each organized community ought to be allowed to decide for itself".[9] Northern Democrats divided almost evenly on the bill, but English was among those who voted for it.[9] In doing so, he said that Congress was bound to respect the decision of the territories' residents (many in Congress did not agree they were so bound) and pledged to uphold their decisions.[11] President Franklin Pierce signed the bill into law on May 30, 1854.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act was grossly unpopular across the North. The reaction ultimately killed the Whig Party, weakened northern Democrats, and brought about a new party, the Republicans. Only 3 of 42 free-state representatives were reelected after voting for it; English was one of them.[12] English was a conservative Democrat, and his southern Indiana district, while not pro-slavery, also had little sympathy for abolitionism.[13] He was reelected again in 1856, when the Democrats regained the House majority in the 35th Congress. The Speaker, James Lawrence Orr, assigned English to the Post Office and Post Roads Committee, but the issue of Kansas claimed more of his time.[14]

English Bill

In December 1857, in an election boycotted by free-state partisans, Kansas adopted the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution and petitioned Congress to be admitted as a slave state.[15] President James Buchanan, a Democrat, urged that Congress take up the matter, and the Senate approved a bill to admit Kansas.[15] English found the process by which the pro-slavery Kansans forced through their constitution inadequate, and voted against admission.[14] The bill was defeated in the House, 120–112. Congress continued to debate the matter for months without resolution. English and Georgia Democrat Alexander Stephens came up with a compromise measure, later called the English Bill.[16] The English Bill offered Kansas admission as a slave state, but only if they endorsed that choice in a referendum. There was a twist to the choice, too, as the Bill only allowed admission if Kansans renounced the unusually large grant of federal lands they had requested in the Lecompton Constitution.[16] The Kansas voters could, thus, reject Lecompton by the face-saving measure of turning down the shrunken land grant.[16] Congress passed the English Bill, and Kansans duly rejected their pro-slavery constitution by a ratio of six to one.[16] Some of English's political allies, including Bright (now a senator), would have preferred Kansas be admitted as a slave state, but the decision was popular enough in his district to allow English to be reelected in 1858 with his largest-ever majority.[17]

Business career

English declined to run for reelection in 1860, but did give several speeches advocating compromise and moderation in the growing North-South divide. After Abraham Lincoln's election that year, English urged Southerners not to secede.[17] When the Southern states did secede and the Civil War began, Governor Oliver P. Morton offered English command of a regiment, but he declined it, having no military knowledge or interests.[18] He did, however, support Morton's (and Lincoln's) war policies and considered himself a War Democrat. English loaned money to the state government to cover the expenses of outfitting the troops and served as provost marshal for the 2nd congressional district.[18]

After retiring from Congress, English spent a year at his home in Scott County before relocating to Indianapolis, the state capital.[18] English and ten associates (including James Lanier) organized the First National Bank of Indianapolis in 1863, the first bank in that city chartered under the new National Bank Act.[19] He remained president of that bank until 1877, including the difficult period during the Panic of 1873, when many other banks folded.[18] English's business interests included other industries as well. He became the controlling shareholder of the Indianapolis Street Railway Company, remaining in charge of that company until 1876, when he sold his shares.[20] Having also sold his shares of the bank by 1877, English turned most of his investment capital to real estate. By 1875, he had already ordered construction of seventy-five houses along what is now English Avenue.[21] By the time he died in 1896, he owned 448 pieces of property, most of them in Indianapolis.[22]

In 1880, English constructed English's Opera House, which was quickly considered Indianapolis's finest.[20] The building was modeled after the Grand Opera House in New York and seated 2000 people.[23] It opened on September 27, 1880, with a performance of Hamlet starring Lawrence Barrett.[23] By that time, English was involved in politics once more, and he turned over management of the Opera House to his son, William Eastin English, who was interested in the theater (and had just married an actress, Annie Fox).[23] English senior later added a hotel to the Opera House, and both operated until 1948.[24]

Vice-presidential candidate

After leaving the House of Representatives, English had remained in touch with local politics, even serving as chairman of the Indiana Democratic Party. His son had been elected to the state House in 1879, and the elder English was still consulted on political matters, but had not sought elected office since 1858.[22] It was in that spirit that English attended the 1880 Democratic National Convention in Cincinnati as a member of the Indiana delegation. English entered the convention favoring Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware, whom he admired for his support of the gold standard.[25] The first ballot was inconclusive, with Bayard in second place and one delegate voting for English.[26] Major General Winfield Scott Hancock of Pennsylvania led the voting, and on the second ballot was nominated for President.[27] The Indiana delegation held back their votes from Hancock until the crucial moment, and as a reward, English was selected for the vice-presidential nomination.[28] The nomination was unanimous. He was not expected to add much to the ticket outside of Indiana, but the party leaders thought his popularity in that swing state would help Hancock against James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur, the Republican nominees.[28] The Republicans believed that the real reason for English's nomination was his willingness to use his personal fortune to finance the campaign, as Democratic campaign coffers were low.[29] English gave a brief speech accepting the nomination, then replied more formally in a letter a month later. In that letter, English called the disputes of the Civil War settled, and promised a "sound currency, of honest money", the restriction of Chinese immigration, and a "rigid economy in public expenditure".[30] He characterized the election as one between

the people endeavoring to regain the political power which rightfully belongs to them, and to restore the pure, simple, economical, constitutional government of our fathers on the one side, and a hundred thousand federal office-holders and their backers, pampered with place and power, and determined to retain them at all hazards, on the other.[31]

Hancock and the Democrats expected to carry the Solid South, which, with the disenfranchisement of blacks following the end of Reconstruction, was dominated electorally by white Democrats.[32] In addition to the South, the ticket needed to add a few of the Midwestern states to their total to win the election; national elections in that era were largely decided by closely divided states there.[33] The practical differences between the parties were few, and the Republicans were reluctant to attack Hancock personally because of his heroic reputation.[34] The one policy difference the Republicans were able to exploit was a statement in the Democratic platform endorsing "a tariff for revenue only".[35] Garfield's campaign used this statement to paint the Democrats as unsympathetic to the plight of industrial laborers, who benefited from the high protective tariff then in place. The tariff issue cut Democratic support in industrialized Northern states, which were essential in establishing a Democratic majority.[36]

The October state elections in Ohio and Indiana resulted in Republican victories there, discouraging Democrats about the federal election to come the following month.[36] There was even some talk among party leaders of dropping English from the ticket, but English convinced them that the October losses owed more to local issues, and that the Democratic ticket could still carry Indiana, if not Ohio, in November.[36] In the end, English was proved wrong: the Democrats and Hancock failed to carry any of the Midwestern states they had targeted, including Indiana. Hancock and English lost the popular vote by just 39,213. The electoral vote, however, had a much larger spread: Garfield-Arthur 214 and Hancock-English 155.[37]

Post-election career

English resumed his business career after the election. He also became more interested in local history, joining a reunion of the survivors of the 1850 state constitutional convention, which met at his opera house in 1885.[22] He became the president of the Indiana Historical Society and wrote two volumes, which were published at his death: Conquest of the Country Northwest of the River Ohio, 1778–1783; and Life of General George Rogers Clark.[38] He served on the Indianapolis Monument Commission in 1893, and helped to plan and finance the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument there.[20]

He died at his home in Indianapolis on February 7, 1896. English was interred in Crown Hill Cemetery with his wife, who had died in 1877. Although many of the buildings he constructed have been demolished, English, Indiana, the county seat of Crawford County, is named after him, as is English Street in Indianapolis.[39] Identical statues of English stand in front of the Scott County Courthouse in Scottsburg, Indiana, and at the Crawford County Fairgrounds in English.[39] His son William served in Congress from 1884 to 1885. His grandson, William English Walling, the son of his daughter Rosalind, was a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.[40] An extensive collection of English's personal and family papers is housed at the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis, where it is open for research.

Notes

- ^ Before the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1913, senators were chosen by their states' legislatures.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Commemorative Biography, p. 9.

- ^ Commemorative Biography, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy et al, p. 220.

- ^ Bright, pp. 370–392.

- ^ a b Commemorative Biography, p. 17.

- ^ Van Bolt, pp. 136–139.

- ^ Van Bolt, p. 141.

- ^ Van Bolt, pp. 155–157.

- ^ a b c d e Commemorative Biography, p. 10.

- ^ a b Freehling 1990, pp. 554–565.

- ^ Russel, p. 201.

- ^ Commemorative Biography, p. 10; Freehling 1990, p. 559.

- ^ Elbert, p. 8.

- ^ a b Commemorative Biography, p. 11.

- ^ a b Freehling 2007, pp. 136–141.

- ^ a b c d Freehling 2007, pp. 142–144.

- ^ a b Commemorative Biography, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Commemorative Biography, p. 13.

- ^ Zeigler, p. 292.

- ^ a b c Nicholas, p. 545.

- ^ Draegart 1954, p. 114.

- ^ a b c Commemorative Biography, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Draegart 1956a, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Worth, p. 547.

- ^ Clancy, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Clancy, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Jordan, pp. 274–280.

- ^ a b Jordan, p. 281.

- ^ Philipp, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Proceedings, p. 168.

- ^ Proceedings, p. 167.

- ^ Clancy, p. 250.

- ^ Jensen, pp. xv–xvi.

- ^ Jordan, pp. 292–296.

- ^ Jordan, p. 297.

- ^ a b c Jordan, pp. 297–301.

- ^ Jordan, p. 306.

- ^ Draegart 1956b, pp. 352–356.

- ^ a b Commemorative Biography, p. 18.

- ^ Craig, p. 352.

Sources

Books

- Commemorative Biographical Record of Prominent and Representative Men of Indianapolis and Vicinity. Chicago, Illinois: J.H. Beers & Co. 1908.

- Clancy, Herbert J. (1958). The Presidential Election of 1880. Chicago, Illinois: Loyola University Press.

- Freehling, William W. (1990). The Road to Disunion: Volume 1 Sessionists at Bay 1776–1854. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-505814-3.

- Freehling, William W. (2007). The Road to Disunion: Volume 2 Secessionists Triumphant 1854–1861. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-505815-1.

- Jensen, Richard J. (1971). The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896. Vol. 2. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-39825-0.

- Jordan, David M. (1996) [1988]. Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier's Life. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21058-5.

- Kennedy, E.B.; Dillaye, S.D.; Hill, Henry (1880). Our Presidential Candidates and Political Compendium. Newark, New Jersey: F.C. Bliss & Co.

- Nicholas, Stacey (1994). "William Hayden English". In Bodenhamer, David J.; Barrows, Robert G. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 544–545. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.

- Official Proceedings of the National Democratic Convention. Dayton, Ohio: [Dayton] Daily Journal Book and Job Room. 1892.

- Worth, Richard W. (1994). "English Hotel and Opera House". In Bodenhamer, David J.; Barrows, Robert G. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 546–547. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.

- Zeigler, Connie J. (1994). "Banking Industry". In Bodenhamer, David J.; Barrows, Robert G. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 291–293. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.

Articles

- "Some Letters of Jesse D. Bright to William H. English (1842–1863)". Indiana Magazine of History. 30 (4): 370–392. 1934. JSTOR 27786698.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Craig, Berry (1998). "William English Walling: Kentucky's Unknown Civil Rights Hero". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 96 (4): 351–376. JSTOR 23384145.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Draegart, Eva (1954). "The Fine Arts in Indianapolis, 1875–1880". Indiana Magazine of History. 50 (2): 105–118. JSTOR 27788180.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Draegart, Eva (1956). "Cultural History of Indianapolis: The Theater, 1880–1890". Indiana Magazine of History. 52 (1): 21–48. JSTOR 27788327.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Draegart, Eva (1956). "Cultural History of Indianapolis: Literature, 1875–1890". Indiana Magazine of History. 52 (4): 343–367. JSTOR 27788390.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Elbert, E. Duane (1974). "Southern Indiana in the Election of 1860: The Leadership and the Electorate". Indiana Magazine of History. 70 (1): 1–23. JSTOR 27789943.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Russel, Robert R. (1963). "The Issues in the Congressional Struggle over the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, 1854". The Journal of Southern History. 29 (2): 187–210. doi:10.2307/2205040. JSTOR 2205040.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Van Bolt, Roger H. (1953). "Indiana in Political Transition, 1851–1853". Indiana Magazine of History. 49 (2): 131–160. JSTOR 27788097.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Thesis

- Philipp, Ernest Joseph (1917). "Chapter 5: The Democratic National Convention". The Presidential Election of 1880 (M.A. thesis). University of Wisconsin.

Manuscript collection

External links

- United States Congress. "William Hayden English (id: E000191)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- William Hayden English at Find A Grave

- United States Congress. "William Hayden English (id: E000191)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery

- Democratic Party (United States) vice presidential nominees

- Indiana Democrats

- Members of the Indiana House of Representatives

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Indiana

- People from Indianapolis, Indiana

- Sons of the American Revolution

- Speakers of the Indiana House of Representatives

- United States vice-presidential candidates, 1880

- Writers from Indiana

- Hanover College alumni

- 1822 births

- 1896 deaths