Central African Republic: Difference between revisions

→Early history: clarification |

→French colonial period: re-wrote and tightened section |

||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

=== French colonial period === |

=== French colonial period === |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{main|Ubangi-Shari}} |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1875 the [[Sudan]]ese sultan [[Rabih az-Zubayr]] governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day CAR. The European penetration of Central African territory began in the late 19th century during the [[Scramble for Africa]].<ref>[http://www.discoverfrance.net/Colonies/Centr_Afr_Rep.shtml French Colonies – Central African Republic]. Discoverfrance.net. Retrieved on 6 April 2013.</ref> Europeans, primarily the French, German, and [[Belgium|Belgians]], arrived in the area in 1885. |

||

{{single source|section|date=June 2014}} |

|||

| ⚫ | The European penetration of Central African territory began in the late 19th century during the [[Scramble for Africa]].<ref>[http://www.discoverfrance.net/Colonies/Centr_Afr_Rep.shtml French Colonies – Central African Republic]. Discoverfrance.net. Retrieved on 6 April 2013.</ref> |

||

France created [[Ubangi-Shari]] territory in 1894. In 1920 [[French Equatorial Africa]] was established and Ubangi-Shari was administered from [[Brazzaville]].<ref>Political Reform in Francophone Africa, Thomas O'Toole, 1997, Westview Press, pg. 111</ref> During the 1920s and 1930s the French introduced a policy of mandatory cotton cultivation.<ref>Political Reform in Francophone Africa, Thomas O'Toole, 1997, Westview Press, pg. 111</ref> |

|||

In 1889, the French established a post on the Ubangi River at Bangui. In 1890–91, de Brazza sent expeditions up the [[Sangha River]], in what is now south-western CAR, up the center of the Ubangi basin toward [[Lake Chad]], and eastward along the Ubangi River toward the [[Nile]], with the intention of expanding the borders of the French Congo to link up the other French territories in Africa. In 1894, the French Congo's borders with [[Leopold II of Belgium]]'s [[Congo Free State]] and [[German Cameroon]] were fixed by diplomatic agreements. In 1899, the French Congo's border with Sudan was fixed along the [[Congo-Nile divide]]. This situation left France without her much coveted outlet on the Nile. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Once European negotiators had agreed upon the borders of the French Congo, France had to decide how to pay for the costly occupation, administration, and development of the territory it had acquired. The reported financial successes of Leopold II's concessionary companies in the Congo Free State convinced the French government to grant 17 private companies large concessions in the Ubangi-Shari region in 1899. In return for the right to exploit these lands by buying local products and selling European goods, the companies promised to pay rent to France and to promote the development of their concessions. The companies employed European and African agents who frequently used brutal methods to force the natives to labor. |

|||

| ⚫ | From 1920 to 1930, a network of roads was built, attempts were made to combat [[African trypanosomiasis|sleeping sickness]] and [[Protestant]] [[Mission (Christianity)|missions]] were established to spread Christianity. New forms of forced labor were also introduced and a large number of Ubangians were sentto work on the [[Congo-Ocean Railway]]. Many of these forced laborers died of exhaustion, illness, or the poor conditions which claimed between 20% and 25% of the 127,000 workers.<ref>2012, Extreme Railways : Congos Jungle Railway, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2xrH6cuoXn4&feature=youtube</ref> |

||

At the same time, the French colonial administration began to force the local population to pay [[tax]]es and to provide the state with free labor. The companies and the French administration at times collaborated in forcing the Central Africans to work for them. Some French officials{{who|date=January 2014}} reported abuses committed by private company militias, and their own colonial colleagues and troops, but efforts to hold these people accountable almost invariably failed. When any news of atrocities committed against Central Africans reached France and caused an outcry, investigations were undertaken and some feeble attempts at reform were made{{by whom|date=January 2014}}, but the [[facts on the ground|situation on the ground]] in Ubangi-Shari remained virtually unchanged.{{Citation needed|date=January 2014}} |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1928, a major insurrection, the [[Kongo-Wara rebellion]] or 'war of the hoe handle', broke out in Western Ubangi-Shari and continued for several years. The extent of this insurrection, which was perhaps the largest anti-colonial rebellion in Africa during the interwar years, was carefully hidden from the French public because it provided evidence of strong opposition to French colonial rule and forced labor. |

||

During the first decade of French colonial rule, from about 1900 to 1910, the rulers of the Ubangi-Shari region increased both their slave-raiding activities and the selling of local produce to Europe. They took advantage of their treaties with the French to procure more [[Firearm|weapons]], which were used to capture more slaves: much of the eastern half of Ubangi-Shari was depopulated as a result of slave-trading by local rulers during the first decade of colonial rule. After the power of local African rulers was destroyed by the French, slave raiding greatly diminished.{{citation needed|date=April 2013}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | From 1920 to 1930, a network of roads was built, |

||

In September 1940, during the [[Second World War]], [[Charles de Gaulle|pro-Gaullist]] French officers took control of Ubangi-Shari and [[General Leclerc]] established his headquarters for the [[Free French Forces]] in [[Bangui]].<ref>[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/102152/Central-African-Republic/40700/The-colonial-era Central African Republic: The colonial era – Britannica Online Encyclopedia]. Britannica.com. Retrieved on 6 April 2013.</ref> In 1946 [[Barthélémy Boganda]] was elected with 9,000 votes to the [[French National Assembly]], becoming the first representative for CAR in the French government. Boganda maintained a political stance against racism and the colonial regime but gradually became disheartened with the French political system and returned to CAR to establish the [[Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa]] (MESAN) in 1950. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In the [[Ubangi-Shari parliamentary election, 1957|Ubangi-Shari Territorial Assembly election]] in 1957, MESAN captured 347,000 out of the total 356,000 votes,<ref>Olson, p. 122.</ref> cast and won every legislative seat,<ref>Kalck (2005), p. xxxi.</ref> which led to Boganda being elected president of the Grand Council of [[French Equatorial Africa]] and vice-president of the Ubangi-Shari Government Council.<ref>Kalck (2005), p. 90.</ref> Within a year, he declared the establishment of the Central African Republic and served as the country's first prime minister. MESAN continued to exist, but its role was limited.<ref name="Kalck2005p136"/> After Boganda's death in a plane crash on 29 March 1959, his cousin, [[David Dacko]], took control of MESAN and became the country's first president after the CAR had formally received [[independence]] from France. Dacko threw out his political rivals, including former Prime Minister and [[Democratic Evolution Movement of Central Africa|Mouvement d'évolution démocratique de l'Afrique centrale]] (MEDAC), leader [[Abel Goumba]], who he forced into exile in France. With all opposition parties suppressed by November 1962, Dacko declared MESAN as the official party of the state.<ref>Kalck (2005), p. xxxii.</ref> |

|||

During the 1930s, [[cotton]], [[tea]], and [[coffee]] emerged as important cash crops in Ubangi-Shari and the mining of [[diamond]]s and [[gold]] began in earnest. Several cotton companies were granted purchasing [[Monopoly|monopolies]] over large areas of cotton production and were able to fix the prices paid to cultivators, which assured profits for their shareholders. In September 1940, during the [[Second World War]], [[Charles de Gaulle|pro-Gaullist]] French officers took control of Ubangi-Shari.<ref>[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/102152/Central-African-Republic/40700/The-colonial-era Central African Republic: The colonial era – Britannica Online Encyclopedia]. Britannica.com. Retrieved on 6 April 2013.</ref> |

|||

=== Independence (1960)=== |

=== Independence (1960)=== |

||

Revision as of 21:46, 6 June 2014

Central African Republic

| |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Unité, Dignité, Travail" (French) "Unity, Dignity, Work" | |

| Anthem: E Zingo (Sango) La Renaissance (French) The Renaissance | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Bangui |

| Official languages | Sango and French |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Demonym(s) | Central African |

| Government | Provisional republic formerly Dominant party presidential republic |

| Catherine Samba-Panza | |

| André Nzapayeké | |

| Legislature | National Assembly (suspended) |

| Independence | |

• from France | 13 August 1960 |

| Area | |

• Total | 622,984 km2 (240,535 sq mi) (45th) |

• Water (%) | 0 |

| Population | |

• 2009 estimate | 4,422,000[1] (124th) |

• 2003 census | 3,895,150 |

• Density | 7.1/km2 (18.4/sq mi) (223rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $3.891 billion[2] |

• Per capita | $800[2] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $2.172 billion[2] |

• Per capita | $446[2] |

| Gini (2008) | 56.3[3] high inequality |

| HDI (2011) | 0.343 low (179th) |

| Currency | Central African CFA franc (XAF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (not observed) |

| Drives on | right[4] |

| Calling code | +236 |

| ISO 3166 code | CF |

| Internet TLD | .cf |

The Central African Republic (CAR; Sango: Ködörösêse tî Bêafrîka; French: République centrafricaine pronounced [ʁepyblik sɑ̃tʁafʁikɛn], or Centrafrique [sɑ̃tʀafʁik]) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad in the north, Sudan in the northeast, South Sudan in the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo in the south and Cameroon in the west. The CAR covers a land area of about 620,000 square kilometres (240,000 sq mi) and has an estimated population of about 4.4 million as of 2008. The capital is Bangui.

France called the colony it carved out in this region Oubangui-Chari, as most of the territory was located in the Ubangi and Chari river basins. From 1910 until 1960, the colony was part of French Equatorial Africa. It became a semi-autonomous territory of the French Community in 1958 and then an independent nation on 13 August 1960, taking its present name. For over three decades after independence, the CAR was ruled by presidents or an emperor, who either were unelected or seized power. Local discontent with this system was eventually reinforced by international pressure, following the end of the Cold War.

The first multi-party democratic elections in the CAR were held in 1993, with the aid of resources provided by the country's donors and help from the United Nations. The elections brought Ange-Félix Patassé to power, but he lost popular support during his presidency and was overthrown in 2003 by General François Bozizé, who went on to win a democratic election in May 2005.[5] Bozizé's inability to pay public sector workers led to strikes in 2007, which led him to appoint a new government on 22 January 2008, headed by Faustin-Archange Touadéra. In February 2010, Bozizé signed a presidential decree which set 25 April 2010 as the date for the next presidential election. This was postponed, but elections were held in January and March 2011, which were won by Bozizé and his party. Despite maintaining a veneer of stability, Bozizé's rule was plagued by heavy corruption, underdevelopment, nepotism, and authoritarianism, which led to an open rebellion against his government. The rebellion was led by an alliance of armed opposition factions known as the Séléka Coalition during the Central African Republic Bush War (2004–2007) and the 2012–2013 Central African Republic conflict. This eventually led to his deposition on 24 March 2013. As a result of the coup d'etat and resulting chaos, governance in the CAR has dissolved and Prime Minister Nicolas Tiangaye has said the country is "anarchy, a non-state."[6] Both the president and prime minister resigned in January, 2014, to be replaced by an interim leader.[7][8]

Most of the CAR consists of Sudano-Guinean savannas, but the country also includes a Sahelo-Sudanian zone in the north and an equatorial forest zone in the south. Two-thirds of the country lie in the basins of the Ubangi River, which flows south into the Congo, while the remaining third lies in the basin of the Chari, which flows north into Lake Chad.

Despite its significant mineral deposits and other resources, such as uranium reserves in Bakouma, crude oil in Vakaga, gold, diamonds, lumber, and hydropower,[9] as well as significant quantities of arable land, the Central African Republic is one of the poorest countries in the world and is among the ten poorest countries in Africa. The Human Development Index for the Central African Republic is 0.343, which places the country as 179th out of those 187 countries with data.

History

|

|---|

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2013) |

Early history

Approximately 10,000 years ago, desertification forced hunter-gatherer societies south into the Sahel regions of northern Central Africa, where some groups settled and began farming as part of the Neolithic Revolution.[10] Initial farming of white yam progressed into millet and sorghum, and the later the domestication of African oil palm improved the groups' nutrition and allowed for expansion of the local populations.[11] Bananas arrived in the region and added an important source of carbohydrates to the diet; they were also used in the production of alcohol.[when?] This Agricultural Revolution, combined with a "Fish-stew Revolution", in which fishing began to take place, and the use of boats, allowed for the transportation of goods. Products were often moved in ceramic pots, which are the first known examples of artistic expression from the region's inhabitants.[12]

The Bouar Megaliths in the western region of the country indicate an advanced level of habitation dating back to the very late Neolithic Era (c. 3500-2700 BC).[13][14] Ironworking arrived in the region around 1000 BC from both Bantu cultures in what is today Nigeria and from the Nile city of Meroë, the capital of the Kingdom of Kush.[15]

During the Bantu Migrations from about 1000 BC to AD 1000, Ubangian-speaking people spread eastward from Cameroon to Sudan, Bantu-speaking people settled in the southwestern regions of the CAR, and Central Sudanic-speaking people settled along the Ubangi River in what is today Central and East CAR.[citation needed]

Production of copper, salt, dried fish, and textiles dominated the economic trade in the Central African region.[16]

16th-18th Century

During the 16th and 17th centuries slave traders began to raid the region and their captives were shipped to the Mediterranean coast, Europe, Arabia, the Western Hemisphere, or to the slave ports and factories along the West African coast.[17] The Bobangi people became major slave traders[when?] and sold their captives to the Americas using the Ubangi river to reach the coast.[18] During the 18th century Bandia-Nzakara peoples established the Bangassou Kingdom along the Ubangi river.[19]

French colonial period

In 1875 the Sudanese sultan Rabih az-Zubayr governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day CAR. The European penetration of Central African territory began in the late 19th century during the Scramble for Africa.[20] Europeans, primarily the French, German, and Belgians, arrived in the area in 1885.

France created Ubangi-Shari territory in 1894. In 1920 French Equatorial Africa was established and Ubangi-Shari was administered from Brazzaville.[21] During the 1920s and 1930s the French introduced a policy of mandatory cotton cultivation.[22]

In 1911, the Sangha and Lobaye basins were ceded to Germany as part of an agreement which gave France a free hand in Morocco. Western Ubangi-Shari remained under German rule until World War I, after which France again annexed the territory using Central African troops.

From 1920 to 1930, a network of roads was built, attempts were made to combat sleeping sickness and Protestant missions were established to spread Christianity. New forms of forced labor were also introduced and a large number of Ubangians were sentto work on the Congo-Ocean Railway. Many of these forced laborers died of exhaustion, illness, or the poor conditions which claimed between 20% and 25% of the 127,000 workers.[23]

In 1928, a major insurrection, the Kongo-Wara rebellion or 'war of the hoe handle', broke out in Western Ubangi-Shari and continued for several years. The extent of this insurrection, which was perhaps the largest anti-colonial rebellion in Africa during the interwar years, was carefully hidden from the French public because it provided evidence of strong opposition to French colonial rule and forced labor.

In September 1940, during the Second World War, pro-Gaullist French officers took control of Ubangi-Shari and General Leclerc established his headquarters for the Free French Forces in Bangui.[24] In 1946 Barthélémy Boganda was elected with 9,000 votes to the French National Assembly, becoming the first representative for CAR in the French government. Boganda maintained a political stance against racism and the colonial regime but gradually became disheartened with the French political system and returned to CAR to establish the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (MESAN) in 1950.

In the Ubangi-Shari Territorial Assembly election in 1957, MESAN captured 347,000 out of the total 356,000 votes,[25] cast and won every legislative seat,[26] which led to Boganda being elected president of the Grand Council of French Equatorial Africa and vice-president of the Ubangi-Shari Government Council.[27] Within a year, he declared the establishment of the Central African Republic and served as the country's first prime minister. MESAN continued to exist, but its role was limited.[28] After Boganda's death in a plane crash on 29 March 1959, his cousin, David Dacko, took control of MESAN and became the country's first president after the CAR had formally received independence from France. Dacko threw out his political rivals, including former Prime Minister and Mouvement d'évolution démocratique de l'Afrique centrale (MEDAC), leader Abel Goumba, who he forced into exile in France. With all opposition parties suppressed by November 1962, Dacko declared MESAN as the official party of the state.[29]

Independence (1960)

On 1 December 1958, the colony of Ubangi-Shari became an autonomous territory within the French Community and took the name Central African Republic. The founding father and president of the Conseil de Gouvernement, Barthélémy Boganda, died in a plane accident in 1959, just eight days before the last elections of the colonial era.

On 13 August 1960, the Central African Republic gained its independence, and two of Boganda's closest aides, Abel Goumba and David Dacko, became involved in a power struggle. With the backing of the French, Dacko took power and soon had Goumba arrested. By 1962, President Dacko had established a one-party state.

Bokassa and the Central African Empire (1965-1979)

On 31 December 1965, Dacko was overthrown in the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état by Colonel Jean-Bédel Bokassa, who suspended the constitution and dissolved the National Assembly. President Bokassa declared himself President for Life in 1972, and named himself Emperor Bokassa I of the Central African Empire (as the country was renamed) on 4 December 1976. A year later, Emperor Bokassa crowned himself in a lavish and expensive ceremony that was ridiculed by much of the world.[30]

In April 1979, young students protested against Bokassa's decree that all school attendees would need to buy uniforms from a company owned by one of his wives. The government violently suppressed the protests, killing 100 children and teenagers. Bokassa himself may have been personally involved in some of the killings.[31] In 1979, France overthrew Bokassa and "restored" Dacko to power (subsequently restoring the name of the country to the Central African Republic). Dacko, in turn, was again overthrown in a coup by General André Kolingba on 1 September 1981.

Central African Republic under Kolingba

Kolingba suspended the constitution and ruled with a military junta until 1985. He introduced a new constitution in 1986 which was adopted by a nationwide referendum. Membership in his new party, the Rassemblement Démocratique Centrafricain (RDC), was voluntary. In 1987, semi-competitive elections to parliament were held, and municipal elections were held in 1988. Kolingba's two major political opponents, Abel Goumba and Ange-Félix Patassé, boycotted these elections because their parties were not allowed to participate.

By 1990, inspired by the fall of the Berlin Wall, a pro-democracy movement became very active. In May 1990, a letter signed by 253 prominent citizens asked for the convocation of a National Conference, but Kolingba refused this request and instead detained several opponents. Pressure from the United States, France, and from a group of locally represented countries and agencies called GIBAFOR (France, the USA, Germany, Japan, the EU, the World Bank, and the UN) finally led Kolingba to agree, in principle, to hold free elections in October 1992 with help from the UN Office of Electoral Affairs.

After using the excuse of alleged irregularities to suspend the results of the elections as a pretext for holding on to power, President Kolingba came under intense pressure from GIBAFOR to establish a "Conseil National Politique Provisoire de la République" (Provisional National Political Council, CNPPR) and to set up a "Mixed Electoral Commission", which included representatives from all political parties.

When elections were finally held in 1993, again with the help of the international community, Ange-Félix Patassé led in the first round and Kolingba came in fourth behind Abel Goumba and David Dacko. In the second round, Patassé won 53% of the vote while Goumba won 45.6%. Most of Patassé's support came from Gbaya, Kare, and Kaba voters in seven heavily populated prefectures in the northwest while Goumba's support came largely from ten less-populated prefectures in the south and east. Furthermore, Patassé's party, the Mouvement pour la Libération du Peuple Centrafricain (MLPC) or Movement for the Liberation of the Central African People, gained a simple but not an absolute majority of seats in parliament, which meant Patassé's party required coalition partners.

Patassé Government (1993–2003)

Patassé relieved former President Kolingba of his military rank of general in March 1994 and then charged several former ministers with various crimes. Patassé also removed many Yakoma from important, lucrative posts in the government. Two hundred predominantly Yakoma members of the presidential guard were also dismissed or reassigned to the army. Kolingba's RDC loudly proclaimed that Patassé's government was conducting a "witch hunt" against the Yakoma.

A new constitution was approved on 28 December 1994 and promulgated on 14 January 1995, but this constitution, like those before it, did not have much impact on the country's politics. In 1996–1997, reflecting steadily decreasing public confidence in the government's erratic behaviour, three mutinies against Patassé's administration were accompanied by widespread destruction of property and heightened ethnic tension. On 25 January 1997, the Bangui Agreements, which provided for the deployment of an inter-African military mission, the Mission Interafricaine de Surveillance des Accords de Bangui (MISAB), were signed. Mali's former president, Amadou Touré, served as chief mediator and brokered the entry of ex-mutineers into the government on 7 April 1997. The MISAB mission was later replaced by a U.N. peacekeeping force, the Mission des Nations Unies en RCA (MINURCA).

In 1998, parliamentary elections resulted in Kolingba's RDC winning 20 out of 109 seats, constituting a comeback. However, in 1999, in spite of widespread public anger in urban centers over his corrupt rule, Patassé won free elections to become president for a second term.

On 28 May 2001, rebels stormed strategic buildings in Bangui in an unsuccessful coup attempt. The army chief of staff, Abel Abrou, and General François N'Djadder Bedaya were killed, but Patassé regained the upper hand by bringing in at least 300 troops of the rebel leader Jean-Pierre Bemba (from across the river in the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and by Libyan soldiers.[citation needed]

In the aftermath of the failed coup, militias loyal to Patassé sought revenge against rebels in many neighborhoods of the capital, Bangui, and incited unrest which resulted in the destruction of many homes as well as the torture and murder of many opponents. Eventually, Patassé came to suspect that General François Bozizé was involved in another coup attempt against him, which led Bozizé to flee with loyal troops to Chad. In March 2003, Bozizé launched a surprise attack against Patassé, who was out of the country. Libyan troops and some 1,000 soldiers of Bemba's Congolese rebel organization failed to stop the rebels, who took control of the country and thus succeeded in overthrowing Patassé. [citation needed]

Central African Republic since 2003

François Bozizé suspended the constitution and named a new cabinet which included most opposition parties. Abel Goumba, known as "Mr. Clean",[citation needed] was named vice-president, which gave Bozizé's new government a positive image. Bozizé established a broad-based National Transition Council to draft a new constitution and announced that he would step down and run for office once the new constitution was approved. A national dialogue was held from 15 September to 27 October 2003, and Bozizé won a fair election that excluded Patassé, and was elected president on a second ballot in May 2005.

In November 2006, the Bozizé government requested French military support to help them repel rebels who had taken control of towns in the country's northern regions.[32] Though the initially public details of the agreement pertained to logistics and intelligence, the French assistance eventually included strikes by Mirage jets against rebel positions.[33]

Bozizé was reelected in an election in 2011 which was widely considered fraudulent.[34]

In November 2012, Séléka, a coalition of rebel groups, took over towns in the northern and central regions of the country. These groups eventually reached a peace deal with the Bozizé's government in January 2013 involving a power sharing government.[34] However, this peace deal was later broken when the rebels who had joined the power sharing government left their posts and stormed the capital. After Bozizé fled the country, Michel Djotodia took over the presidency. In September 2013, Djotodia officially disbanded Seleka, but many rebels refused to disarm and veered further out of government control.[35]

In November 2013, the UN warned the country was at risk of spiraling into genocide[36] and France described the country as "..on the verge of genocide."[37] The increasing violence was largely from reprisal attacks on civilians from Seleka's predominantly Muslim fighters and Christian militias called "anti-balaka", meaning 'anti-machete' or 'anti-sword'.[35] Christians account for approximately half of the population, while Muslims constitute 15 percent. As many Christians have sedentary lifestyles and many Muslims are nomadic, claims to the land were yet another dimension of the conflict.[38]

On 13 December 2013, the UNHCR stated 610 people had been killed in the sectarian violence.[39] Nearly 1 million people, a quarter of the population, were displaced.[40] Anti-balaka Christian militiamen were targeting Bangui's Muslim neighborhoods[40] and Muslim ethnic groups such as the Fula people.[41]

Violence broke out Christmas Day, 2013 in Bangui, the capital of Central African Republic. Six Chadian soldiers from the African Union peacekeeping force were killed on Christmas Day in the Gobongo neighborhood, and a mass grave of 20 bodies was discovered near the presidential palace. A spokesman for the president of the Central African Republic confirmed that assailants had attempted to attack the presidential palace as well, but were pushed back.[42]

On 11 January 2014, Michael Djotodia and his prime minister, Nicolas Tiengaye, resigned as part of a deal negotiated at a regional summit in neighboring Chad.[43] Catherine Samba-Panza was elected as interim president by the National Transitional Council,[44] assuming office on 23 January.

On 18 February 2014, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called on the UN Security Council to immediately deploy 3,000 troops to the country to combat what he described as innocent civilians being deliberately targeted and murdered in large numbers. Noting the violent overthrow of the government in 2013, the collapse of state institutions, and a descent into anarchy and sectarian brutality, Ban said that "the situation in the country has been on the agenda of the Security Council for many years now. But today's emergency is of another, more disturbing magnitude. It is a calamity with a strong claim on the conscience of humankind." The secretary-general outlined a six-point plan, including the addition of 3,000 peacekeepers to bolster the 6,000 African Union soldiers and 2,000 French troops already deployed in the country.[45]

Geography

The Central African Republic is a landlocked nation within the interior of the African continent. It is bordered by Cameroon, Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the Congo. The country lies between latitudes 2° and 11°N, and longitudes 14° and 28°E.

Much of the country consists of flat or rolling plateau savanna approximately 500 metres (1,640 ft) above sea level. Most of the northern half lies within the World Wildlife Fund's East Sudanian savanna ecoregion. In addition to the Fertit Hills in the northeast of the CAR, there are scattered hills in the southwest regions. In the northwest is the Yade Massif, a granite plateau with an altitude of 1,143 feet (348 m).

At 622,941 square kilometres (240,519 sq mi), the Central African Republic is the world's 45th-largest country. It is comparable in size to Ukraine.

Much of the southern border is formed by tributaries of the Congo River; the Mbomou River in the east merges with the Uele River to form the Ubangi River, which also comprises portions of the southern border. The Sangha River flows through some of the western regions of the country, while the eastern border lies along the edge of the Nile River watershed.

It has been estimated that up to 8% of the country is covered by forest, with the most dense parts generally located in the south. The forests are highly diverse and include commercially important species of Ayous, Sapelli and Sipo.[46] The deforestation rate is about 0.4% per annum, and lumber poaching is commonplace.[47]

In the November 2008 issue of National Geographic, the Central African Republic was named the country least affected by light pollution.

|

|

|

Climate

The climate of the Central African Republic is generally tropical, with a wet season that lasts from June to September in the northern regions of the country, and from May to October in the south. During the wet season, rainstorms are an almost daily occurrence, and there early morning fog is commonplace. Maximum annual precipitation is approximately 71 inches (1,800 mm) in the upper Ubangi region.[48]

The northern areas are hot and humid from February to May,[49] but can be subject to the hot, dry, and dusty trade wind known as the Harmattan. The southern regions have a more equatorial climate, but they are subject to desertification, while the extreme northeast regions of the country are already desert.

Demographics

The population of the Central African Republic has almost quadrupled since independence. In 1960, the population was 1,232,000; as of a 2009 UN estimate, it was approximately 4,422,000.[1]

The United Nations estimates that approximately 11% of the population aged between 15 and 49 is HIV positive.[50] Only 3% of the country has antiretroviral therapy available, compared to a 17% coverage in the neighbouring countries of Chad and the Republic of the Congo.[51]

The nation is divided into over 80 ethnic groups, each having its own language. The largest ethnic groups are the Baya, Banda, Mandjia, Sara, Mboum, M'Baka, Yakoma, and Fula or Fulani,[52] with others including Europeans of mostly French descent [9]

Religion

According to the 2003 national census, 80.3% of the population is Christian—51.4% Protestant and 28.9% Roman Catholic—and 15% is Muslim.[53] Animism (9.6%)[citation needed] is also practiced.

The CIA World Factbook reports that approximately fifty percent of the population of CAR are Christians (Protestant 25%, Roman Catholic 25%), while 35% of the population maintain indigenous beliefs and 15% practice Islam,[9] though it is unclear how recent this information is.

There are many missionary groups operating in the country, including Lutherans, Baptists, Catholics, Grace Brethren, and Jehovah's Witnesses. While these missionaries are predominantly from the United States, France, Italy, and Spain, many are also from Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and other African countries. Large numbers of missionaries left the country when fighting broke out between rebel and government forces in 2002–3, but many of them have now returned to continue their work.[54]

Language

The Central African Republic's two official languages are Sangho, a Ngbandi-based creole, and French.

Government and politics

Like many other former French colonies, the Central African Republic's legal system is based upon French law.[55]

A new constitution was approved by voters in a referendum held on 5 December 2004. Full multiparty presidential and parliamentary elections were held in March 2005,[56] with a second round in May; Bozizé was declared the winner after a run-off vote.[57]

A few years later, the Central African Republic fell victim to one of Africa's many civil wars, rebellions, and revolutions. In February 2006, there were reports of widespread violence in the northern part of the country.[58] Thousands of refugees, caught up in the crossfire between government troops and rebel forces, fled their homes; more than 7,000 people fled to neighboring Chad. Those who remained in the CAR spoke of how government troops systematically killed men and boys that they suspected of cooperation with the rebels.[59] The French military supported the Bozizé government's response to the rebels in November 2006.[32][33]

In March 2010, Bozizé signed a decree declaring that presidential elections were to be held on 25 April 2010.[60] However, the elections were postponed, first until 16 May and then indefinitely.[61] However, the general election was eventually set for 23 January 2011. Despite serious organizational problems,[62] the election proceeded as scheduled.[citation needed] A second round was held on 27 March 2011.[citation needed] The general elections were partly funded by the European Union and United Nations Development Programme; the 'Observatoire National des Elections' monitored the election process.[63] Both Bozizé and his party scored major victories.[citation needed]

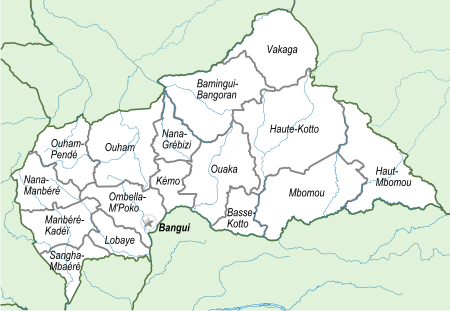

Prefectures and sub-prefectures

The Central African Republic is divided into 16 administrative prefectures (préfectures), two of which are economic prefectures (préfectures economiques), and one an autonomous commune; the prefectures are further divided into 71 sub-prefectures (sous-préfectures).

The prefectures are Bamingui-Bangoran, Basse-Kotto, Haute-Kotto, Haut-Mbomou, Kémo, Lobaye, Mambéré-Kadéï, Mbomou, Nana-Mambéré, Ombella-M'Poko, Ouaka, Ouham, Ouham-Pendé and Vakaga. The economic prefectures are Nana-Grébizi and Sangha-Mbaéré, while the commune is the capital city of Bangui.

Recent events

Despite the veneer of stability during the era, Bozizé's rule was plagued with heavy corruption, underdevelopment, nepotism, and authoritarianism, leading to an open rebellion against the Bozizé government by an alliance of armed opposition factions known as the Séléka Coalition during the Central African Republic Bush War and the 2012–2013 Central African Republic conflict; the uprising eventually led to his ousting on 24 March 2013.

In December 2012, Séléka Coalition rebels advanced towards the capital, prompting protests at the French embassy and the evacuation of the United States embassy.[64] After several days of clashes and rebel advances and the refusal of the French government to intervene, the Bozizé government agreed to hold talks with rebels.[65] However, on 24 March 2013, the Séléka rebels marched into the capital and stormed the presidential palace, forcing Bozizé to flee to Cameroon through the Democratic Republic of Congo.[66][67]

The rebel leader, Djotodia, proclaimed himself President after conquering the capital of Bangui, while Nicolas Tiangaye remained as the prime minister; he had recently been appointed and was allowed by the Séléka rebels to retain his post, as he was endorsed by the opposition.[68]

Resistance against the new rulers consisted mostly of armed youths and soldiers in a base 60 kilometres (37 mi) from the capital. By 27 March, normal life in the capital had begun to resume.[69] Top military and police officers recognized Djotodia as President on 28 March 2013 in what was viewed as "a form of surrender".[70]

A new government was appointed on 31 March 2013, which consisted of members of Séléka and representatives of the opposition to Bozizé, one pro-Bozizé individual,[71][72] and a number representatives of civil society. On 1 April, the former opposition parties declared that they would boycott the government.[73] After African leaders in Chad refused to recognize Djotodia as President, proposing to form a transitional council and the holding of new elections, Djotodia signed a decree on 6 April for the formation of a council that would act as a transitional parliament. The council was tasked with electing a president to serve prior to elections in 18 months.[74]

In November 2013, the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon noted that the security situation in the country remained precarious with government authority nonexistent outside of Bangui,[75] while Jan Eliasson, the UN deputy secretary general said that the CAR was "...descending into complete chaos.."[76] Both the president and prime minister resigned through an announcement at a regional summit in January 2014, after which an interim leader and speaker for the provisional parliament took over.[7][8]

In 2014, Amnesty International reported several massacres committed by the Anti-balaka against Muslim civilians, forcing thousands of Muslims to flee the country.[77][78] Several reports warned that what is going on is a genocide and a wide ethnic-cleansing against Muslims in Central African Republic.

Human rights

The 2009 Human Rights Report by the United States Department of State noted that, in general, the CAR's human rights record remained poor; concerns were expressed over numerous government abuses.[79] Freedom of speech is addressed in the country's constitution, but there have been incidents of government intimidation of the media.[79] A report by the International Research & Exchanges Board's media sustainability index noted that "the country minimally met objectives, with segments of the legal system and government opposed to a free media system".[79]

From 1972 to 1990, and in 2002 and 2003, the CAR was rated 'Not Free' by Freedom House. It was rated 'Partly Free' from 1991–2001 and from 2004 to the present.[80] According to the United Nation's Human Development Index, the country ranks 179 out of 187 countries.[81]

According to the U.S. State Department, major human rights abuses occur in the country. These include: extrajudicial executions by security forces; the torture, beating and rape of suspects and prisoners; impunity, particularly among the armed forces; harsh and life-threatening conditions in prisons and detention centers; arbitrary arrest and detention, prolonged pretrial detention and denial of a fair trial; restrictions on freedom of movement; official corruption; and restrictions on workers' rights. The State Department report also cites widespread mob violence that often results in fatalities, the prevalence of female genital mutilation, discrimination against women and Pygmies, trafficking in persons, forced labor, and child labor. Freedom of movement is limited in the northern part of the country "because of actions by state security forces, armed bandits, and other nonstate armed entities", and due to fighting between government and anti-government forces, many persons have been internally displaced.[82] Approximately 68 percent of the marriages in Central African Republic fall under the category of child marriages.[83]

Foreign relations and military

The Central African Armed Forces were established in 1960. In 2009, the Central African Republic began seeking investments from China.

Foreign aid

The Central African Republic is heavily dependent upon multilateral foreign aid and the presence of numerous NGOs which provide services that the government fails to provide. As one UNDP official stated, the CAR is a country "sous serum", or a country metaphorically hooked up to an IV. (Mehler 2005:150). The mere presence of numerous foreign personnel and organizations in the country, including peacekeepers and even refugee camps, provides an important source of revenue for many Central Africans.[citation needed]

Much of the country is self-sufficient in food crops; however, livestock development is hindered by the presence of the tsetse fly.

In 2006, due to ongoing violence, over 50,000 people in the country's northwest were at risk of starvation.[84] This was only averted thanks to United Nations support.[citation needed]

Peacebuilding Commission

On 12 June 2008, the Central African Republic became the fourth country to be placed on the agenda of the UN Peacebuilding Commission,[85] which was set up in 2005 to help countries emerging from conflict avoid devolving back into war or chaos. The 31-member body agreed to take up the situation after a request from the government.

Peacebuilding Fund

On 8 January 2008, the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon declared that the Central African Republic was eligible to receive assistance from the Peacebuilding Fund.[86] Three priority areas were identified: first, the reform of the security sector; second, the promotion of good governance and the rule of law; and third, the revitalization of communities affected by conflicts.

Economy

Banks in the Central African Republic dispense the CFA franc, which is accepted in a number of different countries. Agriculture is dominated by the cultivation and sale of food crops such as cassava, peanuts, maize, sorghum, millet, sesame, and plantain. The annual real GDP growth rate is just above 3%. The importance of food crops over exported cash crops is indicated by the fact that the total production of cassava, the staple food of most Central Africans, ranges between 200,000 and 300,000 tonnes a year, while the production of cotton, the principal exported cash crop, ranges from 25,000 to 45,000 tonnes a year. Food crops are not exported in large quantities, but still constitute the principal cash crops of the country, because Central Africans derive far more income from the periodic sale of surplus food crops than from exported cash crops such as cotton or coffee.[citation needed]

The Republic's primary import partner is the Netherlands (19.5%). Other imports come from Cameroon (9.7%), France (9.3%), and South Korea (8.7%). Its largest export partner is Belgium (31.5%), followed by China (27.7%), the Democratic Republic of Congo (8.6%), Indonesia (5.2%), and France (4.5%).[9]

The per capita income of the Republic is often listed as being approximately $400 a year, one of the lowest in the world, but this figure is based mostly on reported sales of exports and largely ignores the unregistered sale of foods, locally produced alcohol, diamonds, ivory, bushmeat, and traditional medicine. For most Central Africans, the informal economy of the CAR is more important than the formal economy.[citation needed] Among the mining industry, diamonds constitute the country's most important export, accounting for 40–55% of export revenues, but it is estimated that between 30% and 50% of those produced each year leave the country clandestinely. Export trade is hindered by poor economic development and the country's landlocked position.[citation needed]

The wilderness regions of this country are potential ecotourist destinations. In the southwest, the Dzanga-Sangha National Park is located in a rain forest area. The country is noted for its population of forest elephants and western lowland gorillas. In the north, the Manovo-Gounda St Floris National Park is well-populated with wildlife, including leopards, lions, and rhinos, and the Bamingui-Bangoran National Park is located in the northeast of CAR. The parks have been seriously affected by the activities of poachers, particularly those from Sudan, over the past two decades.[citation needed]

The CAR is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[87] In the 2009 World Bank Group's report Doing Business, it was ranked 183rd of 183 as regards 'ease of doing business', a composite index which takes into account regulations that enhance business activity and those that restrict it.[88]

Infrastructure

Science and technology

Presently, the Central African Republic has active television services, radio stations, internet service providers, and mobile phone carriers; Socatel is the leading provider for both internet and mobile phone access throughout the country. The primary governmental regulating bodies of telecommunications are the Ministère des Postes and Télécommunications et des Nouvelles Technologies. In addition, the Central African Republic receives international support on telecommunication related operations from ITU Telecommunication Development Sector (ITU-D) within the International Telecommunication Union to improve infrastructure.

Transportation

The Central African Republic has over 1,800 motor vehicles on the road, although a relatively limited quantity of land has been developed into highways.

Energy

The Central African Republic primarily uses hydroelectricity as there are few other resources for energy.

Education

Public education in the Central African Republic is free and is compulsory from ages 6 to 14.[89] However, approximately half of the adult population of the country is illiterate.[90]

Higher education

The University of Bangui, a public university located in Bangui which includes a medical school, and Euclid University, an international university in Bangui, are the two institutions of higher education in the Central African Republic.

Health

The largest hospitals are in the country located in the Bangui district. Fortunately, there are also Air Ambulances which provide transportation to larger hospitals for citizens outside of the area. As a member of the World Health Organization, the Central African Republic also receives various vaccination assistance, such as a 2014 intervention for the prevention of a measles epidemic.[91] In 2007, female life expectancy at birth was 48.2 years and male life expectancy at birth was 45.1 years.[92] The fertility rate is approximately five births per woman.[92] According to 2009 estimates, the HIV/AIDS prevalence rate is about 4.7% of the adult population (ages 15–49).[93] Government expenditure on health was at US$ 20 (PPP) per person in 2006.[92] There were around 0.05 physicians per 1000 people in 2009.[94] Government expenditure on health was at 10.9% of total government expenditure in 2006.[92]

Culture

Music

Sports

The Central African Republic national football team, which is governed by the Fédération Centrafricaine de Football, stages matches at Barthelemy Boganda Stadium.

References

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects, Table A.1" (PDF). 2008 revision. United Nations. 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

"Note: estimates for this country take into account the effects of excess mortality due to AIDS; this can result in lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality and death rates, lower population and growth rates, and changes in the distribution of population by age and sex than would otherwise be expected." - ^ a b c d "Central African Republic". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Which side of the road do they drive on? Brian Lucas. August 2005. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ CELEBRATING, LOOTING FOLLOW COUP, U.N. CONDEMNS TAKEOVER IN CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC. Lexington Herald-Leader, 18 March 2003

- ^ Violent and Chaotic, Central African Republic Lurches Toward a Crisis. (August 7, 2013) Adam Nossiter. New York Times.

- ^ a b "CAR interim President Michel Djotodia resigns". BBC. 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Central African Republic leader says chaos is over". BBC. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d "CIA World Factbook Central African Republic". Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ The History of Central and Eastern Africa, Amy McKenna, 2011, pg. 4

- ^ The History of Central and Eastern Africa, Amy McKenna, 2011, pg. 5

- ^ The History of Central and Eastern Africa, Amy McKenna, 2011, pg. 4

- ^ Methodology and African Prehistory by, UNESCO. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa, pg. 548

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage, Les mégalithes de Bouar, http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/4003/

- ^ The History of Central and Eastern Africa, Amy McKenna, 2011, pg. 7

- ^ The History of Central and Eastern Africa, Amy McKenna, 2011, pg. 10

- ^ Central Africa Republic Timeline -- Part 1: From Prehistory to Independence (13 August 1960), A Chronology of Key Events in Central Africa Republic, By Alistair Boddy-Evans, About.com, http://africanhistory.about.com/od/car/l/bl-CAR-Timeline-1.htm

- ^ "Central African Republic". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Central Africa Republic Timeline -- Part 1: From Prehistory to Independence (13 August 1960), A Chronology of Key Events in Central Africa Republic, By Alistair Boddy-Evans, About.com, http://africanhistory.about.com/od/car/l/bl-CAR-Timeline-1.htm

- ^ French Colonies – Central African Republic. Discoverfrance.net. Retrieved on 6 April 2013.

- ^ Political Reform in Francophone Africa, Thomas O'Toole, 1997, Westview Press, pg. 111

- ^ Political Reform in Francophone Africa, Thomas O'Toole, 1997, Westview Press, pg. 111

- ^ 2012, Extreme Railways : Congos Jungle Railway, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2xrH6cuoXn4&feature=youtube

- ^ Central African Republic: The colonial era – Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Britannica.com. Retrieved on 6 April 2013.

- ^ Olson, p. 122.

- ^ Kalck (2005), p. xxxi.

- ^ Kalck (2005), p. 90.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Kalck2005p136was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Kalck (2005), p. xxxii.

- ^ a b 'Cannibal' dictator Bokassa given posthumous pardon. The Guardian. 3 December 2010

- ^ "'Good old days' under Bokassa?". BBC News. 2 January 2009

- ^ a b "CAR hails French pledge on rebels". BBC. 14 November 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ a b "French planes attack CAR rebels". BBC. 30 November 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Central African Republic". CIA. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ a b Smith, David (22 November 2013) Unspeakable horrors in a country on the verge of genocide The Guardian, Retrieved 23 November 2013

- ^ "UN warning over Central African Republic genocide risk". bbcnews.com. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ "France says Central African Republic on verge of genocide". reuters.com. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ "'We Live and Die Here Like Animals'". foreignpolicy.com. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ More than 600 killed in week of Central African Republic violence: UN

- ^ a b "Eight dead in Central African Republic capital, rebel leaders flee city". Reuters. January 26, 2014.

- ^ "Central African Republic militia 'killed' children". BBC News. December 4, 2013.

- ^ AP (26 December 2013). "Attack On Presidential Palace Thwarted In Bangui". Leaker. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ CAR interim President Michel Djotodia resigns

- ^ Paul-Marin Ngoupana. "Central African Republic's capital tense as ex-leader heads into exile". Uk.reuters.com. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "More military help sought by UN to protect CAR civilians". The Africa News.Net. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Sold Down the River (English) March 2001, Forests Monitor

- ^ Template:Wayback. CARPE 13 July 2007

- ^ Central African Republic: Country Study Guide volume 1, p. 24.

- ^ Ward, Inna, ed. (2007). Whitaker's Almanack (139th ed.). London: A & C Black. p. 796. ISBN 0-7136-7660-4.

- ^ "Central African Republic". Unaids.org. 29 July 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ ANNEX 3: Country progress indicators. 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. unaids.org

- ^ In Fula: Fulɓe; in French: Peul

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2010". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "Central African Republic. International Religious Freedom Report 2006". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ "Legal System". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "Reuters AlertNet – CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC: Poll results to be announced on 22 May, official says". Alertnet.org. 11 May 2005. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Timeline: Central African Republic". BBC News. 9 March 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Thousands flee new CAR 'rebels'". BBC News. 24 February 2006. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Thousands flee from CAR violence". BBC News. 25 March 2006. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Central African Republic to hold April 25 elections | Top News | Reuters". Af.reuters.com. 25 February 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "BozizĂŠ prend ses prĂŠcautions Afrique Subsaharienne, Politique". Jeuneafrique.com. 15 May 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Les problèmes de gestion à la Commission Electorale Indépendante seraient-ils un frein au bon déroulement du processus électoral?". Journal des Elections. 20 December 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ "Les publications de l'ONE". Journal des Elections. 20 December 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ "Central African Republic's Bozize in US-France appeal". BBC. 27 December 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Central African Republic to hold talks with rebels". BBC. 28 December 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "Central African Republic president flees capital amid violence, official says". CNN. 24 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (25 March 2013). "Leader of Central African Republic Fled to Cameroon, Official Says". The New York Times.

- ^ Fort, Patrick (26 March 2013). "Looters rampage in CAR as strongman set to unveil government". Mail and Guardian. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Pockets of resistance still in Central African Republic

- ^ Ange Aboa, "C.African Republic army chiefs pledge allegiance to coup leader", Reuters, 28 March 2013.

- ^ "Rebels, opposition form government in CentrAfrica: decree", Agence France-Presse, 31 March 2013.

- ^ "Centrafrique : Nicolas Tiangaye présente son gouvernement d'union nationale", Jeune Afrique, 1 April 2013 Template:Fr icon.

- ^ Ange Aboa, "Central African Republic opposition says to boycott new government", Reuters, 1 April 2013.

- ^ "C. Africa strongman forms transition council", AFP, 6 April 2013.

- ^ Rick Gladstone (18 November 2013), Central African Republic Stirs Concern The New York Times

- ^ (26 November 2013) Central African Republic 'descending into chaos' – UN BBC News Africa, Retrieved 26 November 2013

- ^ http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/feb/14/muslim-convoy-central-african-republic-exodus

- ^ http://www.globalresearch.ca/france-and-the-militarization-of-central-africa-thousands-of-muslims-fleeing-the-central-african-republic/5369276

- ^ a b c 2009 Human Rights Report: Central African Republic. U.S. Department of State, 11 March 2010.

- ^ "FIW Score". Freedom House. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "Central African Republic". International Human Development Indicators. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "2010 Human Rights Report: Central African Republic". US Department of State. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "Child brides around the world sold off like cattle". USA Today. 8 March 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ CAR: Food shortages increase as fighting intensifies in the northwest. irinnews.org, 29 March 2006

- ^ "Peacebuilding Commission Places Central African Republic On Agenda; Ambassador Tells Body 'CAR Will Always Walk Side By Side With You, Welcome Your Advice'". Un.org. 2 July 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Central African Republic Peacebuilding Fund – Overview. United Nations.

- ^ "OHADA.com: The business law portal in Africa". Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ^ Template:Wayback, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, 2009, ISBN 978-0-8213-7961-5, doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-7961-5. |accessdate=22 November 2013

- ^ "Central African Republic". Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor (2001). Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Central African Republic – Statistics". UNICEF. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ http://www.who.int/hac/crises/caf/en/

- ^ a b c d "Human Development Report 2009 – Central African Republic". Hdrstats.undp.org. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ CIA World Factbook: HIV/AIDS – adult prevalence rate. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 6 April 2013.

- ^ "WHO Country Offices in the WHO African Region – WHO | Regional Office for Africa". Afro.who.int. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

Further reading

- Doeden, Matt, Central African Republic in Pictures (Twentyfirst Century Books, 2009).

- Kalck, Pierre, Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic, 2004.

- Petringa, Maria, Brazza, A Life for Africa (2006). ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0.

- Titley, Brian, Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa, 2002.

- Woodfrok, Jacqueline, Culture and Customs of the Central African Republic (Greenwood Press, 2006).

External links

- Overviews

- Centrafrique.com

- Country Profile from BBC News

- "Central African Republic". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Central African Republic from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Central African Republic at Curlie

Wikimedia Atlas of the Central African Republic

Wikimedia Atlas of the Central African Republic- Key Development Forecasts for the Central African Republic from International Futures

- Government

- Central African Republic Online Template:En icon/Template:Fr icon

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members – Central Intelligence Agency

- News

- Humanitarian news and analysis from IRIN – Central African Republic

- Humanitarian information coverage on ReliefWeb

- Central African Republic news headline links from AllAfrica.com

- Other

- Central African Republic at Humanitarian and Development Partnership Team (HDPT)

- Johann Hari in Birao, Central African Republic. "Inside France's Secret War" from The Independent, 5 October 2007

- Use dmy dates from April 2013

- Central African Republic

- Countries in Africa

- French-speaking countries and territories

- Landlocked countries

- Least developed countries

- Member states of La Francophonie

- Member states of the African Union

- Member states of the United Nations

- Republics

- States and territories established in 1960

- Central African countries