Mud March (suffragists): Difference between revisions

→Press reaction: sp per original |

Cutting part of background as re-write |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Under construction}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=February 2014}} |

|||

{{ |

{{EngvarB|date=June 2018}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2018}} |

|||

[[File:Mud-march-poster.jpg |thumb|Poster advertising the march and meeting, 9 February 1907]] |

[[File:Mud-march-poster.jpg |thumb|Poster advertising the march and meeting, 9 February 1907]] |

||

The '''United Procession of Women''', or '''Mud March''' as it became known, was a peaceful demonstration in London on 9 February 1907 organised by the [[National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies]] (NUWSS), in which more than three thousand women marched from [[Hyde Park Corner]] to the [[Strand, London|Strand]] in support of votes for women. Women from all classes participated in what was the largest public demonstration supporting [[women's suffrage]] seen up to that date. It acquired the name "Mud March" from the day's weather, when incessant heavy rain left the marchers drenched and mud-spattered. |

The '''United Procession of Women''', or '''Mud March''' as it became known, was a peaceful demonstration in London on 9 February 1907 organised by the [[National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies]] (NUWSS), in which more than three thousand women marched from [[Hyde Park Corner]] to the [[Strand, London|Strand]] in support of votes for women. Women from all classes participated in what was the largest public demonstration supporting [[women's suffrage]] seen up to that date. It acquired the name "Mud March" from the day's weather, when incessant heavy rain left the marchers drenched and mud-spattered. |

||

The proponents of women's suffrage were divided between those who favoured constitutional methods and those who supported [[direct action]]. In 1903 [[Emmeline Pankhurst]] formed the [[Women's Social and Political Union]] (WSPU) |

The proponents of women's suffrage were divided between those who favoured constitutional methods and those who supported [[direct action]]. In 1903 [[Emmeline Pankhurst]] formed the [[Women's Social and Political Union]] (WSPU). Known as the [[suffragettes]], the WSPU held demonstrations, heckled politicians, and from 1905 saw several of its members imprisoned, gaining press attention and increased support from women. To maintain that momentum and create support for a new suffrage bill in the [[House of Commons]], the NUWSS and other groups organised the Mud March to coincide with the opening of Parliament. The event attracted much public interest and broadly sympathetic press coverage, but when the bill was presented the following month, it was [[Filibuster#Westminster-style parliaments|"talked out"]] without a vote.{{sfn|Hume|2016|p=35}} |

||

While the march failed to influence the immediate parliamentary process, it had a considerable impact on public awareness and on the movement's future tactics. Large peaceful public demonstrations, never previously attempted, became standard features of the suffrage campaign; on 21 June 1908 up to half a million people attended [[Women's Sunday]], a WSPU rally in [[Hyde Park, London|Hyde Park]].{{sfn|Holten|2003|p=46}} The marches showed that the fight for women's suffrage had the support of women in every stratum of society, who despite their social differences were able to unite and work together for a common cause. |

While the march failed to influence the immediate parliamentary process, it had a considerable impact on public awareness and on the movement's future tactics. Large peaceful public demonstrations, never previously attempted, became standard features of the suffrage campaign; on 21 June 1908 up to half a million people attended [[Women's Sunday]], a WSPU rally in [[Hyde Park, London|Hyde Park]].{{sfn|Holten|2003|p=46}} The marches showed that the fight for women's suffrage had the support of women in every stratum of society, who despite their social differences were able to unite and work together for a common cause. |

||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

===History=== |

|||

{{further|Timeline of women's suffrage|Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom}} |

{{further|Timeline of women's suffrage|Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom}} |

||

[[File:Harriet Mill from NPG.jpg|thumb|upright|left|[[Harriet Taylor Mill]]]] |

|||

<!--In his history of the franchise in Britain, [[Paul Foot]] indicates that, in the middle of the seventeenth century, the issue of women's suffrage was alive and perhaps acceptable to certain of the [[Levellers]], although the movement as a whole sought merely an extension of the male franchise.{{refn|[[Paul Foot]] (2012): "In his diatribe against [[William Walwyn]], the royalist hack [[Francis Edwards]] had accused the Levellers of wanting to extend the vote even to women. Such an extension would not have worried the rationalist and libertarian Walwyn. [[Edward Sexby]] was an Anabaptist, which sect had a proud record of egalitarian treatment of women, including the encouragement of women preachers. But the woman question, like the servant question, was a difficult one, and those early pamphlets tended to ignore it. They would be satisfied, the Levellers indicated, with a wide extension of an annual male franchise."{{sfn|Foot|2012|p=10}}|group=n}}{{Additional citation needed|date=March 2018|reason=scholarly source needed}}-->When the [[Reform Act 1832|Reform Act of 1832]] was being debated, the radical MP [[Henry Hunt (politician)|Henry Hunt]] presented a petition to parliament from Mary Smith of Stanmore—whom he described as "a lady of rank and fortune"—asking that "every unmarried female, possessing the necessary pecuniary qualification, should be entitled to vote for Members of Parliament". Smith argued that as a taxpayer she ought to have a "share in the election of a Representative", and further that, because women are "liable to all the punishments of the law", they ought to have a voice in making the law, but even during their trials the judges and jurors were men.<ref>{{cite Hansard|house=House of Commons |title=Rights of women |url=http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1832/aug/03/rights-of-women#S3V0014P0_18320803_HOC_4 |date=3 August 1832 |volume=14|column=1086}}; {{harvnb|Belchem|2004}}.</ref><!--Mention Bentham--> In the 1840s the cause was taken up by elements within the [[Chartism|Chartists]]. Although women's suffrage was not a Chartist policy, one of the movement's leaders, R. J. Richardson, expressed his support in a pamphlet, "The Rights of Woman" (1840).{{sfn|Richardson|1971|p=125}} In 1851, after Chartism had largely withered, [[Harriet Taylor Mill]]'s "Enfranchisement of Women" was published anonymously in the ''Westminster Review''. In it she asked: |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

<blockquote>[W]ith what truth or rationality could the suffrage be termed universal, while half the human species remain excluded from it? To declare that a voice in the government is the right of all, and demand it for only a part – the part, namely, to which the claimant himself belongs – is to renounce even the appearance of principle.{{sfn|Mill|1868|p=6}}</blockquote> |

|||

<!-- Essential parameters --> |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| header = |

|||

| width = 150 |

|||

<!-- Image 1 --> |

|||

| image1 = Millicent Fawcett - Women Wanted.jpg |

|||

| width1 = |

|||

| alt1 = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

<!-- Image 2 --> |

|||

| image2 = Emmeline Pankhurst, seated (1913).jpg |

|||

| width2 = |

|||

| alt2 = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In October 1897 [[Millicent Fawcett]] was the driving force behind the formation of the [[National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies]] (NUWSS), a new umbrella organisation for all the factions and regional societies, and to liaise with sympathetic [[Member of parliament#United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland|MPs]]. Initially, seventeen groups affiliated to the new central body. The organisation became the leading body following a constitutional path to women's suffrage.{{sfn|Hawksley|2017|p=64}}{{sfn|"Founding of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies", UK Parliament}}{{sfn|Holton|2008}} In October 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel Pankhurst formed a women-only group in Manchester, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), although there was some overlap in the membership of the organisations.{{sfn|Purvis|1998|p=157}}{{sfn|Holton|2017}} |

|||

At the time of the Mud March, before the suffragette campaign had progressed to damaging property, relations between the WSPU and NUWSS remained cordial.{{sfn|Cowman|2010|p=65}} When eleven suffragettes were jailed in October 1906 after a protest in the [[House of Commons]] lobby, Fawcett and the NUWSS stood by them; on 27 October 1906, in a letter to ''The Times'', she wrote: |

|||

[[File:John Stuart Mill, Punch, 30 March 1867.jpeg|thumb|upright=1.1|"Mill's logic; or, franchise for females", ''[[Punch (magazine)|Punch]]'' magazine, 30 March 1867]] |

|||

On 7 June 1866, the philosopher and recently elected MP [[John Stuart Mill]], who was married to Harriet Taylor Mill until her death in 1858, presented a petition to parliament on behalf of [[Barbara Bodichon]] (later one of the founders of [[Girton College, Cambridge]],{{sfn|Herstein|2012|p=85}} asking that all householders be enfranchised no matter their sex. Bodichon and her friends collected 1,499 signatures, among them those of many leading women educationists and social reformers, including [[Frances Buss]], [[Josephine Butler]], [[Frances Power Cobbe]], [[Emily Davies]], [[Harriet Martineau]], [[Priscilla Bright McLaren]], [[Bessie Rayner Parkes]], [[Mary Somerville]] and [[Clementia Taylor]].<ref>{{harvnb|Holton|2002|pp=19–21}}; [http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/overview/petitions/ "Women and the Vote: Petitions"], UK Parliament; {{cite web|title= Women and the Vote: Collecting the signatures for the 1866 petition|url= https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/parliamentary-collections/1866-suffrage-petition/collecting-the-signatures/|publisher= UK Parliament|accessdate= 2 March 2018}}</ref>{{refn|In 1867 the property qualification meant that about 33 percent of adult men were entitled to the vote. Later legislation increased this proportion to around 67 percent before 1918.{{sfn|Pilkington|1999|p=134}}|group=n}} However, the following year Mill's attempt to embody the petition's demands in the [[Second Reform Act 1867]] failed.<ref>{{cite web|title= Women and the Vote: Presenting the 1866 petition |url= https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/parliamentary-collections/1866-suffrage-petition/presenting-the-petition/ |publisher= UK Parliament|accessdate= 2 March 2018}}</ref> Thereupon, women began to organise and form local suffrage societies, which had some success in gaining votes for women in municipal elections, despite making no progress on the parliamentary front.{{sfn|Foot|2012|p=180}} |

|||

| ⚫ | {{quotation|The real responsibility for these sensational methods lies with the politicians, misnamed statesmen, who will not attend to a demand for justice until it is accompanied by some form of violence. Every kind of insult and abuse is hurled at the women who have adopted these methods, especially by the "reptile" press. But I hope the more old-fashioned suffragists will stand by them; and I take this opportunity of staying that in my opinion, far from having injured the movement, they have done more during the last twelve months to bring it within the region of practical politics than we have been able to accomplish in the same number of years.<ref>{{harvnb|Hume|2016|p=30}}, citing {{cite news |last1=Fawcett |first1=Millicent |authorlink1=Millicent Fawcett |title=The Imprisoned Suffragists |work=The Times |date=27 October 1906 |page=9}}</ref>}} |

||

=== National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In 1867 a national body, the [[National Society for Women's Suffrage]] (NSWS) was formed, through the efforts of [[Lydia Becker]].{{sfn|Walker|2004}} Among the early NSWS members was the 20-year-old [[Millicent Garrett Fawcett]], who became a leading figure in the movement; she was active in the campaign against the [[Representation of the People Act 1884|Third Reform Act of 1884]], which extended the male franchise but again excluded women.<ref>{{harvnb|Howarth|2007}}; {{cite web|title= Third Reform Act 1884|url= http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/houseofcommons/reformacts/overview/one-man-one-vote/|publisher= UK Parliament|accessdate= 11 March 2018}}</ref> In October 1897 Fawcett chaired a meeting at which the NSWS was subsumed into the [[National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies]] (NUWSS), a new umbrella organisation for all the regional societies.<ref>* {{cite web|title= Inaugural NUWSS meeting minutes and Notice of formation of the NUWSS (1897)|url= http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/unesco/nuwss-foundation/|date=1897|publisher= Central and Western Society for Women's Suffrage (courtesy of UK Parliament)|accessdate= 2 March 2018|page=2}}</ref><!--the description of 1888 doesn't seem to be correct (see, for example, Purvis 2003, p. 29): After repeated parliamentary rebuffs, some members began to advocate more militant methods; as early as 1888 the NSWS's Central Committee had split between "moderates" such as Fawcett and those such as [[Emmeline Pankhurst]] who argued for a more robust approach.{{sfn|Abrams|2003|p=185}}--> |

|||

| ⚫ | The militant actions of the WSPU raised the profile of the women's suffrage campaign in Britain and the NUWSS wanted to show that they were as committed as the suffragettes to the cause.{{sfn|Hume|2016|p=32}}{{sfn|Smith|2014|p=23}} In January 1906 the [[Liberal Party (UK)|Liberal Party]], led by [[Henry Campbell-Bannerman]], had won an overwhelming [[United Kingdom general election, 1906|general election victory]]; although before the election many Liberal MPs had promised that the [[Liberal government, 1905–1915|new administration]] would introduce a women's suffrage bill, once in power, Campbell-Bannerman said that it was "not realistic" to introduce new legislation.{{sfn|Hawksley|2017|p=129}} A month after the election, the WSPU held a successful London march, attended by 300–400 women.{{sfn|Kelly|2004|pp=333–334}} To show there was support for a suffrage bill, the Central Society for Women's Suffrage suggested, in November 1906, holding a mass procession in London to coincide with the opening of Parliament in February.{{sfn|Tickner|1988|p=74}}{{sfn|Hume|2016|p=32}} The NUWSS called on its members to join in.{{sfn|Hume|2016|p=34}} |

||

In October 1903 [[Emmeline Pankhurst]] and her daughter [[Christabel Pankhurst]] formed a women-only group in Manchester, the [[Women's Social and Political Union]] (WSPU), with the motto "deeds, not words". The WPSU focused exclusively on the "woman question", ignoring party politics and class issues.{{sfn|Purvis|2018|p=68}} Whereas the NUWSS sought its objectives through constitutional means, such as petitions to parliament,{{sfn|Purvis|2018|p=2}} the WSPU organised open-air meetings and heckled politicians, choosing jail over fines when prosecuted.{{refn|In October 1905, after [[Annie Kenney]] and Christabel Pankhurst were thrown out of a meeting in Manchester for heckling [[Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon|Sir Edward Grey]], Pankhurst committed a "technical assault" of a police officer to force an arrest; the women refused to pay a fine and received a seven-day prison sentence.{{sfn|Smith|2014|p=39}}|group=n}} On 10 January 1906 the ''[[Daily Mail]]'' coined the term ''suffragettes'' for them, a label they adopted as a badge of honour.<ref>{{harvnb|Atkinson|2018|loc=709–715}}, citing ''Daily Mail'', 10 January 1906, p. 3; also see {{harvnb|Holton|2002|p=253}}, citing Helen Moyes (1971). ''A Woman in a Man's World''. Sydney: Alpha Books, p. 92, who named the journalist as Charles E. Hands.{{pb}} |

|||

{{cite web|first=Lynda|last=Mugglestone|title= Woman – or ''Suffragette?''|url= https://blog.oup.com/2013/04/suffragette-word-origin-evolution-etymology/|website=OUPblog|publisher=Oxford University Press|date=9 April 2013}}</ref>{{refn|At the time of the march, the distinction between ''suffragists'' and ''suffragettes'' was not always recognised in press reports; ''suffragette'' was used as a blanket term for all women's suffrage activists. For example, see {{harvnb|''The Observer'', "Lady Day", 10 February 1907}}; {{harvnb|''Daily Mirror'', 11 February 1907}}; {{harvnb|''The Illustrated London News'', 16 February 1907}}; and {{harvnb|''The Sphere'', 16 February 1907}}.|group= n}} At the time of the Mud March, before the suffragette campaign had progressed to damaging property, relations between the WSPU and NUWSS remained cordial.{{refn|Krista Cowman (2010): "In February 1907 the NUWSS organised the first large-scale suffrage procession in London, which was dubbed the 'Mud March' because of the inclement weather. Millicent Fawcett was initially conciliatory towards the WSPU and praised the way that militant tactics had raised the profile of suffrage. The Mud March shows that the NUWSS changed its methods to adopt more public forms of activity in response to the suffragettes. It arranged similar events up to the outbreak of the First World War, including a national [[Great Pilgrimage|suffrage pilgrimage]] which converged in London from all over Britain in 1913. However, relations between constitutional and militant societies cooled as militancy advanced, and the NUWSS formally condemned militancy in 1908."{{sfn|Cowman|2010|p=65}}{{pb}} |

|||

The NUWSS issued statements in October 1908, November 1909 and December 1911 condemning "the use of violence in political propaganda". Referring to those statements, Fawcett wrote in 1911: "I admit fully that the kind and degree of violence carried out by the so-called 'suffragettes' is of the mildest description: a few panes of glass have been broken, and meetings have been disturbed, but no one has suffered in life or limb; our great movement towards freedom has not been stained by serious crime. ... Far more violence has been suffered by the suffragettes than they have caused their opponents to suffer."{{sfn|Fawcett|1911|p=64}}.{{pb}}Also see {{harvnb|Lethbridge|2018}}; {{harvnb|Hume|2016|pp=28–30}}; {{harvnb|Smith|2014|p=25}}; {{harvnb|Pugh|2000|p=182}}; {{harvnb|van Wingerden|1999|p=96}}; {{harvnb|Fawcett|1925|pp=183, 185, 192}}.|group=n}} When eleven suffragettes were jailed in October 1906 after a protest in the House of Commons lobby, Millicent Fawcett and the NUWSS stood by them; on 24 October an NUWSS meeting of 2,000 women applauded the suffragettes, and the NUWSS held a banquet for them at the [[Savoy Hotel|Savoy]] when they were released.<ref>For 2,000 women, see {{harvnb|Purvis|2003|p=88}}; for the banquet, {{harvnb|Hume|2016|pp=30–32}} and {{harvnb|Fawcett|1925|p=188}}; for the Savoy, {{harvnb|Crawford|2003|p=261}}.</ref> Fawcett wrote in a letter to ''The Times'' that October: |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | {{quotation|The real responsibility for these sensational methods lies with the politicians, misnamed statesmen, who will not attend to a demand for justice until it is accompanied by some form of violence. Every kind of insult and abuse is hurled at the women who have adopted these methods, especially by the "reptile" press. But I hope the more old-fashioned suffragists will stand by them; and I take this opportunity of staying that in my opinion, far from having injured the movement, they have done more during the last twelve months to bring it within the region of practical politics than we have been able to accomplish in the same number of years.<ref>{{harvnb|Hume|2016|p=30}}, citing |

||

The NUWSS wanted to show that they were as committed as the suffragettes to the cause.{{sfn|Hume|2016|p=32}} In January 1906 the [[liberal Party (UK)|Liberal Party]], led by [[Henry Campbell-Bannerman]], had won an overwhelming [[United Kingdom general election, 1906|general election victory]], and many expected the [[Liberal government, 1905–1915|new administration]] to introduce a women's suffrage bill.{{refn|"The Enfranchisement of Women. To the Editor of the ''Manchester Guardian''.{{pb}} |

|||

"Sir,—In your principal leader yesterday you affirm that no Government ought to make the enfranchisement of women an integral part of its policy without giving the electors due notice and the opportunity of declaring themselves. It is scarcely possible that you suggest, for this question alone, an absolute referendum to the whole male electorate. If you mean anything short of this, will you allow me to remind your readers that in 1905 the General Committee of the National Liberal Federation passed a women's suffrage resolution by 117 votes to 19, and the General Council of that body by 'an overwhelming majority,' as your own columns bore witness—a course followed later in the year by the National Reform Union. Surely here is 'mandate' sufficient to warrant decisive and immediate action on the part of any just or wise Liberal Administration.{{pb}} "It should be remembered that both political parties frequently make certain proposals 'an integral part of their policy' on much weaker evidence as to the opinions of their official organisations on those proposals.—Yours, &c., [[Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme Elmy|Elizabeth C. Wolstenholme Elmy]], [[Congleton]], February 12 [1907]."{{pb}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

==March== |

==March== |

||

===Organisation=== |

===Organisation=== |

||

[[File:Philippa Strachey in 1921 (cropped).jpg|thumb|upright=0.9|left|[[Pippa Strachey]]]] |

[[File:Philippa Strachey in 1921 (cropped).jpg|thumb|upright=0.9|left|[[Pippa Strachey]]]] |

||

The task of organising the event, scheduled for Saturday, 9 February 1907, was delegated to [[Pippa Strachey]]{{sfn|Caine|2004}} of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage.{{ |

The task of organising the event, scheduled for Saturday, 9 February 1907, was delegated to [[Pippa Strachey]]{{sfn|Caine|2004}} of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage.{{efn|In 1907 the Central Society for Women's Suffrage, the organiser of the Mud March, became the London Society for Women's Suffrage (LSWS).{{sfn|Crawford|2003|p=104}} Based at 25 [[Victoria, London|Victoria Street]], with 62 London branches, it was a middle-class organisation with the aim, according to Sowon S. Park, of "equal suffrage". By 1912 it had 4,000 members and 20,000 "friends". It became the London Society for Women's Service in 1919. [[Pippa Strachey]] was secretary of the LSWS from 1914 to 1919 and secretary of the London Society for Women's Service from 1919 to 1926, when the latter became the London and National Society for Women's Service.{{sfn|Park|2005|p=125}} }} Her mother, Lady [[Jane Maria Strachey|Jane Strachey]], a friend of Fawcett, was a long-standing suffragist, but Pippa Strachey had shown little interest in the issue before a meeting with [[Emily Davies]], who quickly converted her to the cause. She took on the organisation of the London march with no experience of doing anything similar, but carried out the task so effectively that she was given responsibility for the planning of all future large processions of the NUWSS.{{sfn|Caine|2004}} |

||

Regional suffrage societies and other organisations were invited to bring delegations to the march. [[Lisa Tickner]] writes that "all sensibilities and political disagreements had to be soothed" to make sure the various groups would take part. The Women's Cooperative Guild would attend only if certain conditions were met, and the [[British Women's Temperance Association]] and [[Women's Liberal Federation]] (WLF) would not attend if the WSPU was formally invited. The WLF—a "crucial lever on the Liberal government", according to Tickner—objected to the WSPU's criticism of the government. |

Regional suffrage societies and other organisations were invited to bring delegations to the march. The art historian [[Lisa Tickner]] writes that "all sensibilities and political disagreements had to be soothed" to make sure the various groups would take part. The Women's Cooperative Guild would attend only if certain conditions were met, and the [[British Women's Temperance Association]] and [[Women's Liberal Federation]] (WLF) would not attend if the WSPU was formally invited. The WLF—a "crucial lever on the Liberal government", according to Tickner—objected to the WSPU's criticism of the government.{{sfn|Tickner|1988|p=74}}{{sfn|Smith|2014|p=23}} At the time of the march, ten of the twenty women who sat on the NUWSS executive committee were connected to the Liberal Party.{{sfn|Hume|2016|p=36}} |

||

The march would begin at [[Hyde Park Corner]] and progress via [[Piccadilly]] to [[Exeter Hall]], a large meeting venue on the [[Strand, London|Strand]].{{sfn|Hill|2002|p=154}} A second, open-air meeting was scheduled for [[Trafalgar Square]].{{sfn| |

The march would begin at [[Hyde Park Corner]] and progress via [[Piccadilly]] to [[Exeter Hall]], a large meeting venue on the [[Strand, London|Strand]].{{sfn|Hill|2002|p=154}} A second, open-air meeting was scheduled for [[Trafalgar Square]].{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators" ("Mr Hardie's Speech"), 10 February 1907}} Members of the [[Artists' Suffrage League]] produced posters and postcards, and designed and produced around eighty embroidered banners for the march.<ref>{{cite web|title= Pastscape: the former studio of the Artists Suffrage League |url= http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=1520606|publisher= Historic England|accessdate= 4 March 2018}}</ref> In all, around forty organisations from all over the country chose to participate.<ref name= NatArch>{{cite web|title= Procession and Speeches (extract from the ''Daily Mail'', 11 February 1907)|url= https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/britain1906to1918/pdf/gallery-4-gaining-suffrage-case-studies.pdf|publisher= The National Archives|page= 37|accessdate= 4 March 2018}}</ref> |

||

===9 February=== |

===9 February=== |

||

| Line 47: | Line 49: | ||

On the morning of 9 February, large numbers of women converged on the march's starting point, the [[Wellington Monument, London|statue of Achilles]] near Hyde Park Corner.{{sfn|Pankhurst|1911|p=135}} Between three and four thousand women were assembled, from all ages and strata of society, in appalling weather with incessant rain; "mud, mud, mud" was the dominant feature of the day, wrote Fawcett.{{sfn|Fawcett|1925|p=190}} The marchers included [[Frances Balfour|Lady Frances Balfour]], sister-in-law of [[Arthur Balfour]], the former [[Conservative Party (UK)|Conservative]] prime minister; [[Rosalind Howard, Countess of Carlisle|Rosalind Howard]], the Countess of Carlisle, of the Women's Liberal Federation; the poet and trade unionist [[Eva Gore-Booth]]; and the veteran campaigner Emily Davies.{{sfn|Crawford|2003|pp=30, 98, 159, 250}} The march's aristocratic representation was matched by numbers of professional women – doctors, schoolmistresses, artists{{sfn|Tickner|1988|p=75, citing the ''Tribune''}} – and large contingents of working women from northern and other provincial cities, marching under banners that proclaimed their varied trades: bank-and-bobbin winders, cigar makers, clay-pipe finishers, power-loom weavers, shirt makers.{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators" ("The Procession"), 10 February 1907}} |

On the morning of 9 February, large numbers of women converged on the march's starting point, the [[Wellington Monument, London|statue of Achilles]] near Hyde Park Corner.{{sfn|Pankhurst|1911|p=135}} Between three and four thousand women were assembled, from all ages and strata of society, in appalling weather with incessant rain; "mud, mud, mud" was the dominant feature of the day, wrote Fawcett.{{sfn|Fawcett|1925|p=190}} The marchers included [[Frances Balfour|Lady Frances Balfour]], sister-in-law of [[Arthur Balfour]], the former [[Conservative Party (UK)|Conservative]] prime minister; [[Rosalind Howard, Countess of Carlisle|Rosalind Howard]], the Countess of Carlisle, of the Women's Liberal Federation; the poet and trade unionist [[Eva Gore-Booth]]; and the veteran campaigner Emily Davies.{{sfn|Crawford|2003|pp=30, 98, 159, 250}} The march's aristocratic representation was matched by numbers of professional women – doctors, schoolmistresses, artists{{sfn|Tickner|1988|p=75, citing the ''Tribune''}} – and large contingents of working women from northern and other provincial cities, marching under banners that proclaimed their varied trades: bank-and-bobbin winders, cigar makers, clay-pipe finishers, power-loom weavers, shirt makers.{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators" ("The Procession"), 10 February 1907}} |

||

Although the WSPU was not officially represented, many suffragettes attended, including Christabel Pankhurst, [[Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence|Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence]], [[Annie Kenney]], [[Anne Cobden-Sanderson]], [[Nellie Martel]], [[Edith How-Martyn]], [[Flora Drummond]], [[Charlotte Despard]] and [[Gertrude Ansell]]. |

Although the WSPU was not officially represented, many suffragettes attended, including Christabel Pankhurst, [[Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence|Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence]], [[Annie Kenney]], [[Anne Cobden-Sanderson]], [[Nellie Martel]], [[Edith How-Martyn]], [[Flora Drummond]], [[Charlotte Despard]] and [[Gertrude Ansell]].{{sfn|Atkinson|2018|p=60}}{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators", 10 February 1907}}{{sfn|''The Sphere'', 16 February 1907}} According to the historian [[Diane Atkinson]], "belonging to both organisations, going to each others' events and wearing both badges was quite usual".{{sfn|Atkinson|2018|p=60}} |

||

[[File:Mud March, 9 February 1907, Illustrated London News.jpg||thumb|upright=1.3|left|At the head of the march ''(left to right)'', Lady [[Frances Balfour]] in the light coat, [[Millicent Garrett Fawcett]], and Lady [[Jane Maria Strachey|Jane Strachey]]]] |

[[File:Mud March, 9 February 1907, Illustrated London News.jpg||thumb|upright=1.3|left|At the head of the march ''(left to right)'', Lady [[Frances Balfour]] in the light coat, [[Millicent Garrett Fawcett]], and Lady [[Jane Maria Strachey|Jane Strachey]]]] |

||

By around 2.30 pm the march had formed a line that stretched far down [[Rotten Row]]. It set off in the drenching rain, with a brass band leading and Lady Frances Balfour, Millicent Fawcett, and Lady Jane Strachey at the head of the column.{{sfn|Hume|2016|p=34}} The procession was followed by a phalanx of carriages and motor cars, many of which carried flags bearing the letters "WS" and bouquets of red and white flowers.{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators", 10 February 1907}} Despite the weather, thousands thronged the pavements to enjoy the novel spectacle of "respectable women marching in the streets", according to Harold Smith.{{sfn|Smith|2014|p=23}} |

By around 2.30 pm the march had formed a line that stretched far down [[Rotten Row]]. It set off in the drenching rain, with a brass band leading and Lady Frances Balfour, Millicent Fawcett, and Lady Jane Strachey at the head of the column.{{sfn|Hume|2016|p=34}} The procession was followed by a phalanx of carriages and motor cars, many of which carried flags bearing the letters "WS" and bouquets of red and white flowers.{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators", 10 February 1907}} Despite the weather, thousands thronged the pavements to enjoy the novel spectacle of "respectable women marching in the streets", according to Harold Smith.{{sfn|Smith|2014|p=23}} |

||

''[[The Observer]]''{{'}}s reporter recorded that "there was hardly any of the derisive laughter which had greeted former female demonstrations",{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators" ("The Procession"), 10 February 1907}} although ''[[The Morning Post]]'' reported "scoffs and jeers of enfranchised males who had posted themselves along the line of the route, and appeared to regard the occasion as suitable for the display of crude and vulgar jests".{{sfn|''The Morning Post'', 11 February 1907}} [[Katharine Frye]], who joined the march at [[Piccadilly Circus]], recorded "not much joking at our expense and no roughness".<ref name= Frye>{{cite web|last= Crawford|first= Elizabeth| title= Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: The Mud March, 9 February 1907|url= https://womanandhersphere.com/2012/11/21/kate-fryes-suffrage-diary-the-mud-march-9-february-1907/|publisher= Woman and her Sphere|accessdate= 10 March 2018}}</ref>{{sfn|Crawford|2013|p=29}} The ''[[Daily Mail]]'' |

''[[The Observer]]''{{'}}s reporter recorded that "there was hardly any of the derisive laughter which had greeted former female demonstrations",{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators" ("The Procession"), 10 February 1907}} although ''[[The Morning Post]]'' reported "scoffs and jeers of enfranchised males who had posted themselves along the line of the route, and appeared to regard the occasion as suitable for the display of crude and vulgar jests".{{sfn|''The Morning Post'', 11 February 1907}} [[Katharine Frye]], who joined the march at [[Piccadilly Circus]], recorded "not much joking at our expense and no roughness".<ref name= Frye>{{cite web|last= Crawford|first= Elizabeth| title= Kate Frye’s Suffrage Diary: The Mud March, 9 February 1907|url= https://womanandhersphere.com/2012/11/21/kate-fryes-suffrage-diary-the-mud-march-9-february-1907/|publisher= Woman and her Sphere|accessdate= 10 March 2018}}</ref>{{sfn|Crawford|2013|p=29}} The ''[[Daily Mail]]''--which supported women's suffrage—carried an eyewitness account, "How It Felt", by [[Constance Smedley]] of the Lyceum Club. Smedley described a divided reaction from the crowd: "that shared by the poorer class of men, namely, bitter resentment at the possibility of women getting any civic privilege they had not got; the other that of amusement at the fact of women wanting any serious thing ... badly enough to face the ordeal of a public demonstration".<ref>{{harvnb|Kelly|2004|p=337}}, citing the ''Daily Mail'', 11 February 1907, p. 7.</ref> |

||

Approaching Trafalgar Square the march divided: representatives from the northern industrial towns broke off for an open-air meeting at [[Nelson's Column]],{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators" ("Mr Hardie's Speech"), 10 February 1907}} while the main march continued to Exeter Hall, for a meeting chaired by the Liberal politician [[Walter McLaren]], whose wife, [[Eva McLaren]], was one of the scheduled speakers.<ref name= Frye/> [[Keir Hardie]], leader of the [[Labour Party (UK)|Labour Party]], told the meeting, to hissing from several Liberal women on the platform, that if women won the vote, it would be thanks to the "suffragettes' fighting brigade". |

Approaching Trafalgar Square the march divided: representatives from the northern industrial towns broke off for an open-air meeting at [[Nelson's Column]],{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators" ("Mr Hardie's Speech"), 10 February 1907}} while the main march continued to Exeter Hall, for a meeting chaired by the Liberal politician [[Walter McLaren]], whose wife, [[Eva McLaren]], was one of the scheduled speakers.<ref name= Frye/> [[Keir Hardie]], leader of the [[Labour Party (UK)|Labour Party]], told the meeting, to hissing from several Liberal women on the platform, that if women won the vote, it would be thanks to the "suffragettes' fighting brigade".{{sfn|Atkinson|2018|p=60}}{{sfn|Pankhurst|1911|p=135}} He spoke strongly in favour of the meeting's resolution, which was carried, that women be given the vote on the same basis as men,{{sfn|Crawford|2003|p=273}} and demanded a bill in the current parliamentary session.<ref name= NatArch/> At the Trafalgar Square meeting, Eva Gore-Booth referred to the "alienation of the Labour Party through the action of a certain section in the suffrage movement", according to ''The Observer'', and asked the party "not to punish the millions of women workers" because of the actions of a small minority. When Hardie arrived from Exeter Hall, he expressed the hope that "no working man bring discredit on the class to which he belonged by denying to women those political rights which their fathers had won for them".{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Titled Demonstrators" ("Mr Hardie's Speech"), 10 February 1907}} |

||

==Aftermath== |

==Aftermath== |

||

| Line 61: | Line 63: | ||

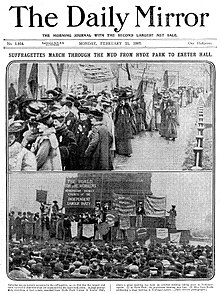

The press coverage gave the movement "more publicity in a week", according to one commentator, "than it had enjoyed in the previous fifty years".{{sfn|Hill|2002|p=154}} [[Lisa Tickner]] writes that the reporting was "inflected by the sympathy or otherwise of particular newspapers for the suffrage cause".{{sfn|Tickner|1988|p=75}} The ''[[Daily Mirror]]'', neutral on the issue of women's suffrage, offered a large photospread,{{sfn|Kelly|2004|p=337}} and praised the crowd's diversity: "Never in the history of the suffragette movement has there been such a company as that which, representative of all classes, from a peeress to the humblest working woman, assembled to join in the procession."{{sfn|''Daily Mirror'', 11 February 1907}} ''[[The Times]]'', an opponent of women's suffrage,{{sfn|Kelly|2004|p=337}} thought the event "remarkable as much for its representative character as for its size", describing the scenes and speeches in detail over 20 column inches.<ref>{{harvnb|Kelly|2004|p=338}}, citing {{harvnb|''The Times'', 11 February 1907|p=11}}.</ref> The protesters had had to "run the gauntlet of much inconsiderate comment", according to the ''[[Daily Chronicle]]'' (supportive).<ref>{{harvnb|Kelly|2004|p=337}}, citing the ''Daily Chronicle'', 11 February 1907, p. 6.</ref> The pictorial journal ''[[The Sphere]]'' provided a montage of photographs under the headline "The Attack on Man's Supremacy".{{sfn|''The Sphere'', 16 February 1907}} |

The press coverage gave the movement "more publicity in a week", according to one commentator, "than it had enjoyed in the previous fifty years".{{sfn|Hill|2002|p=154}} [[Lisa Tickner]] writes that the reporting was "inflected by the sympathy or otherwise of particular newspapers for the suffrage cause".{{sfn|Tickner|1988|p=75}} The ''[[Daily Mirror]]'', neutral on the issue of women's suffrage, offered a large photospread,{{sfn|Kelly|2004|p=337}} and praised the crowd's diversity: "Never in the history of the suffragette movement has there been such a company as that which, representative of all classes, from a peeress to the humblest working woman, assembled to join in the procession."{{sfn|''Daily Mirror'', 11 February 1907}} ''[[The Times]]'', an opponent of women's suffrage,{{sfn|Kelly|2004|p=337}} thought the event "remarkable as much for its representative character as for its size", describing the scenes and speeches in detail over 20 column inches.<ref>{{harvnb|Kelly|2004|p=338}}, citing {{harvnb|''The Times'', 11 February 1907|p=11}}.</ref> The protesters had had to "run the gauntlet of much inconsiderate comment", according to the ''[[Daily Chronicle]]'' (supportive).<ref>{{harvnb|Kelly|2004|p=337}}, citing the ''Daily Chronicle'', 11 February 1907, p. 6.</ref> The pictorial journal ''[[The Sphere]]'' provided a montage of photographs under the headline "The Attack on Man's Supremacy".{{sfn|''The Sphere'', 16 February 1907}} |

||

In its leading article, ''[[The Observer]]'' warned that "the vital civic duty and natural function of women ... is the healthy propagation of race", and that the aim of the movement was "nothing less than complete sex emancipation".{{ |

In its leading article, ''[[The Observer]]'' warned that "the vital civic duty and natural function of women ... is the healthy propagation of race", and that the aim of the movement was "nothing less than complete sex emancipation".{{efn|"Lady Day", ''[[The Observer]]'', 10 February 1907: "It is not so much who is to mind the baby—babies and nurses there will ever be and they bring their own consolations—but a question concerning the fundamental idea of sex, and the effects physical, mental and economic, that any revolutionary change in the conditions of women's life must have on the vital civic duty and natural function of women—which is the healthy propagation of race. For the vote is, of course, merely the beginning of the larger policy. What is aimed at is nothing less than complete sex emancipation; the right of women not only to vote, but to enter public life on equal conditions with men. It is a physical problem before all things, and an economic problem of great complexity and difficulty. It cannot be solved by shouting; its positive side cannot be answered at all until it has been submitted to the test of experience by any man, doctor or scientist, or by any woman. It is the fact that woman are not educated to take any rational interest in politics, history, economics, science, philosophy or the serious side of life, which they, as the embodiment of the lighter side, are brought up, and have been brought up since the days of Edenic beginnings, to consider as the privilege and property of the stronger sex. The small section of women who desire the vote completely ignore the educational feature of the whole question, as they do the natural laws of physical force and the teachings of history about men and Government."{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Lady Day", 10 February 1907}} }} It was concerned that women were not ready for the vote: "If women had the vote tomorrow, how many would use it, still more, how many would be able to use it to any honest, intelligible purpose?" The movement should educate its own sex, rather than "seeking to confound men". The newspaper nevertheless welcomed that there had been "no attempts to bash policemen's helmets, to tear down the railings of the Park, to utter piercing war cries ..."{{sfn|''The Observer'', "Lady Day", 10 February 1907}} Likewise, ''[[The Daily News (UK)|The Daily News]]'' compared the event favourably to the actions of suffragettes: "Such a demonstration is far more likely to prove the reality of the demand for a vote than the practice of breaking up meetings held by Liberal Associations."{{sfn|''Daily News'', 11 February 1907}} ''[[The Manchester Guardian]]'' agreed: "For those ... who, like ourselves, wish to see this movement – a great movement, as will one day be recognised – carried through in such a way as to win respect even where it cannot command agreement Saturday's demonstration was of good omen."{{sfn|''Manchester Guardian'', 11 February 1907}} |

||

===Dickinson Bill=== |

===Dickinson Bill=== |

||

| Line 67: | Line 69: | ||

Four days after the march, the NUWSS executive met with the Parliamentary Committee for Women's Suffrage (founded 1893) to discuss a [[Private Members' Bills in the Parliament of the United Kingdom|private member's bill]].<ref>{{harvnb|Hume|2016|p=34}}; [http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/93f31ae0-6ac3-4bc8-8c75-a4d34763361a "Parliamentary Committee for Women's Suffrage Archive"], The National Archives.</ref> On the same day, the suffragettes held their first "Women's Parliament" at [[Caxton Hall]], after which 400 women marched toward the Commons to protest against the omission from the [[State Opening of Parliament|King's Speech]], the day before, of a women's suffrage bill; over 60 were arrested, and 53 chose prison over a fine.<ref>[https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/talked-out-pamphlet "Talked Out! pamphlet"], British Library; {{harvnb|Purvis|2018|pp=126–127}}.</ref> |

Four days after the march, the NUWSS executive met with the Parliamentary Committee for Women's Suffrage (founded 1893) to discuss a [[Private Members' Bills in the Parliament of the United Kingdom|private member's bill]].<ref>{{harvnb|Hume|2016|p=34}}; [http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/93f31ae0-6ac3-4bc8-8c75-a4d34763361a "Parliamentary Committee for Women's Suffrage Archive"], The National Archives.</ref> On the same day, the suffragettes held their first "Women's Parliament" at [[Caxton Hall]], after which 400 women marched toward the Commons to protest against the omission from the [[State Opening of Parliament|King's Speech]], the day before, of a women's suffrage bill; over 60 were arrested, and 53 chose prison over a fine.<ref>[https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/talked-out-pamphlet "Talked Out! pamphlet"], British Library; {{harvnb|Purvis|2018|pp=126–127}}.</ref> |

||

On 26 February 1907 the Liberal MP for [[St Pancras North (UK Parliament constituency)|St Pancras North]], [[Willoughby Dickinson]], published the text of a bill proposing that women should have the vote subject to the same property qualification that applied to men. This would, it was estimated, enfranchise at least two million women.{{ |

On 26 February 1907 the Liberal MP for [[St Pancras North (UK Parliament constituency)|St Pancras North]], [[Willoughby Dickinson]], published the text of a bill proposing that women should have the vote subject to the same property qualification that applied to men. This would, it was estimated, enfranchise at least two million women.{{efn|''[[Manchester Guardian]]'' (27 February 1907): "Little fault is found with Mr. Dickinson's bill even by the most militant of women suffragists. Mrs. Pankhurst expressed her opinion yesterday to a representative of the ''Manchester Guardian'' that the bill would have the immediate effect of enfranchising 2,000,000 women, very much the larger proportion of which number would be working women."{{sfn|''Manchester Guardian'', 27 February 1907}}|}}{{Primary source inline|date=March 2018}} (On the day the bill was published, the [[Cambridge Union]] passed by a small majority a motion "that this House would view with regret the extension of the franchise to women".){{sfn|''Manchester Guardian'', 27 February 1907}} Although the bill received strong backing from the suffragist movement, it was viewed more equivocally in the House of Commons, particularly by some Labour members who regarded it as giving more votes to the propertied classes, but doing nothing for working women.{{rfn|''[[Manchester Guardian]]'' (28 February 1907): "Mr. Dickinson's bill is said to have met with the unanimous approval of women suffragists, but in the House of Commons it is regarded with scant favour either by Liberal or Labour members. Mr. [[Keir Hardie]] [Labour leader] is in favour of the widest possible extension of women's suffrage, and supports Mr. Dickinson's view that marriage should be no barrier to a woman exercising the franchise. He is also in favour of the removal of the property qualification which at present limits the franchise, and regards the bill as a step to universal adult suffrage. ... Mr. [[Philip Snowden]] [Labour MP] regards the removal of the property qualification, which would otherwise prevent married women of the working classes from exercising their vote as joint occupiers, as an essential part of any scheme for women's suffrage ... But this view is not generally shared by Liberal or Labour members, and the Liberal-Labour view on the bill may be summed up in [[Fred Maddison|Mr. Maddison]]'s [Liberal MP] words: 'I do not regard the bill,' he said, 'as an extension of the franchise to the sex so much as the endowment of a propertied class with votes. In this way it will create a new class of pluralist votes, and in my view no bill that does not give absolute security against the restriction of the joint occupier's vote to the ₤20 house ought to receive the support of the Labour party. A bill that excludes the working-class woman, as I believe this bill does, excludes that democratic basis for woman's suffrage which I believe to be its only justification.'{{sfn|''Manchester Guardian'', 28 February 1907}}}}{{Primary source inline|date=March 2018}} On 8 March Dickinson introduced his Women's Enfranchisement Bill to the House of Commons for its [[second reading]], with a plea that members should not be swayed by their distaste for militant actions;{{sfn|Hume|2016|pp=34–35}} the House of Commons "Ladies Gallery" was kept closed during the debate in case of protests by the [[WSPU]].<ref>[https://ukvote100.org/2017/08/23/the-ladies-gallery-grilles/ "Gone grille: The removal of the Ladies' Gallery grilles"], UK Vote 100, 23 August 2017.</ref> The debate was inconclusive and the bill was [[Filibuster#Westminster-style parliaments|"talked out"]] without a vote.<ref>{{harvnb|Hume|2016|p=35}}; {{harvnb|''Manchester Guardian'', 9 March 1907}}.</ref> The NUWSS had worked hard for the bill and found the response insulting.{{sfn|Hume|2016|p=35}} |

||

===Legacy=== |

===Legacy=== |

||

Revision as of 20:44, 6 June 2018

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by SchroCat (talk | contribs) 6 years ago. (Update timer) |

The United Procession of Women, or Mud March as it became known, was a peaceful demonstration in London on 9 February 1907 organised by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), in which more than three thousand women marched from Hyde Park Corner to the Strand in support of votes for women. Women from all classes participated in what was the largest public demonstration supporting women's suffrage seen up to that date. It acquired the name "Mud March" from the day's weather, when incessant heavy rain left the marchers drenched and mud-spattered.

The proponents of women's suffrage were divided between those who favoured constitutional methods and those who supported direct action. In 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Known as the suffragettes, the WSPU held demonstrations, heckled politicians, and from 1905 saw several of its members imprisoned, gaining press attention and increased support from women. To maintain that momentum and create support for a new suffrage bill in the House of Commons, the NUWSS and other groups organised the Mud March to coincide with the opening of Parliament. The event attracted much public interest and broadly sympathetic press coverage, but when the bill was presented the following month, it was "talked out" without a vote.[1]

While the march failed to influence the immediate parliamentary process, it had a considerable impact on public awareness and on the movement's future tactics. Large peaceful public demonstrations, never previously attempted, became standard features of the suffrage campaign; on 21 June 1908 up to half a million people attended Women's Sunday, a WSPU rally in Hyde Park.[2] The marches showed that the fight for women's suffrage had the support of women in every stratum of society, who despite their social differences were able to unite and work together for a common cause.

Background

In October 1897 Millicent Fawcett was the driving force behind the formation of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), a new umbrella organisation for all the factions and regional societies, and to liaise with sympathetic MPs. Initially, seventeen groups affiliated to the new central body. The organisation became the leading body following a constitutional path to women's suffrage.[3][4][5] In October 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel Pankhurst formed a women-only group in Manchester, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), although there was some overlap in the membership of the organisations.[6][7]

At the time of the Mud March, before the suffragette campaign had progressed to damaging property, relations between the WSPU and NUWSS remained cordial.[8] When eleven suffragettes were jailed in October 1906 after a protest in the House of Commons lobby, Fawcett and the NUWSS stood by them; on 27 October 1906, in a letter to The Times, she wrote:

The real responsibility for these sensational methods lies with the politicians, misnamed statesmen, who will not attend to a demand for justice until it is accompanied by some form of violence. Every kind of insult and abuse is hurled at the women who have adopted these methods, especially by the "reptile" press. But I hope the more old-fashioned suffragists will stand by them; and I take this opportunity of staying that in my opinion, far from having injured the movement, they have done more during the last twelve months to bring it within the region of practical politics than we have been able to accomplish in the same number of years.[9]

The militant actions of the WSPU raised the profile of the women's suffrage campaign in Britain and the NUWSS wanted to show that they were as committed as the suffragettes to the cause.[10][11] In January 1906 the Liberal Party, led by Henry Campbell-Bannerman, had won an overwhelming general election victory; although before the election many Liberal MPs had promised that the new administration would introduce a women's suffrage bill, once in power, Campbell-Bannerman said that it was "not realistic" to introduce new legislation.[12] A month after the election, the WSPU held a successful London march, attended by 300–400 women.[13] To show there was support for a suffrage bill, the Central Society for Women's Suffrage suggested, in November 1906, holding a mass procession in London to coincide with the opening of Parliament in February.[14][10] The NUWSS called on its members to join in.[15]

March

Organisation

The task of organising the event, scheduled for Saturday, 9 February 1907, was delegated to Pippa Strachey[16] of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage.[a] Her mother, Lady Jane Strachey, a friend of Fawcett, was a long-standing suffragist, but Pippa Strachey had shown little interest in the issue before a meeting with Emily Davies, who quickly converted her to the cause. She took on the organisation of the London march with no experience of doing anything similar, but carried out the task so effectively that she was given responsibility for the planning of all future large processions of the NUWSS.[16]

Regional suffrage societies and other organisations were invited to bring delegations to the march. The art historian Lisa Tickner writes that "all sensibilities and political disagreements had to be soothed" to make sure the various groups would take part. The Women's Cooperative Guild would attend only if certain conditions were met, and the British Women's Temperance Association and Women's Liberal Federation (WLF) would not attend if the WSPU was formally invited. The WLF—a "crucial lever on the Liberal government", according to Tickner—objected to the WSPU's criticism of the government.[14][11] At the time of the march, ten of the twenty women who sat on the NUWSS executive committee were connected to the Liberal Party.[19]

The march would begin at Hyde Park Corner and progress via Piccadilly to Exeter Hall, a large meeting venue on the Strand.[20] A second, open-air meeting was scheduled for Trafalgar Square.[21] Members of the Artists' Suffrage League produced posters and postcards, and designed and produced around eighty embroidered banners for the march.[22] In all, around forty organisations from all over the country chose to participate.[23]

9 February

On the morning of 9 February, large numbers of women converged on the march's starting point, the statue of Achilles near Hyde Park Corner.[24] Between three and four thousand women were assembled, from all ages and strata of society, in appalling weather with incessant rain; "mud, mud, mud" was the dominant feature of the day, wrote Fawcett.[25] The marchers included Lady Frances Balfour, sister-in-law of Arthur Balfour, the former Conservative prime minister; Rosalind Howard, the Countess of Carlisle, of the Women's Liberal Federation; the poet and trade unionist Eva Gore-Booth; and the veteran campaigner Emily Davies.[26] The march's aristocratic representation was matched by numbers of professional women – doctors, schoolmistresses, artists[27] – and large contingents of working women from northern and other provincial cities, marching under banners that proclaimed their varied trades: bank-and-bobbin winders, cigar makers, clay-pipe finishers, power-loom weavers, shirt makers.[28]

Although the WSPU was not officially represented, many suffragettes attended, including Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Annie Kenney, Anne Cobden-Sanderson, Nellie Martel, Edith How-Martyn, Flora Drummond, Charlotte Despard and Gertrude Ansell.[29][30][31] According to the historian Diane Atkinson, "belonging to both organisations, going to each others' events and wearing both badges was quite usual".[29]

By around 2.30 pm the march had formed a line that stretched far down Rotten Row. It set off in the drenching rain, with a brass band leading and Lady Frances Balfour, Millicent Fawcett, and Lady Jane Strachey at the head of the column.[15] The procession was followed by a phalanx of carriages and motor cars, many of which carried flags bearing the letters "WS" and bouquets of red and white flowers.[30] Despite the weather, thousands thronged the pavements to enjoy the novel spectacle of "respectable women marching in the streets", according to Harold Smith.[11]

The Observer's reporter recorded that "there was hardly any of the derisive laughter which had greeted former female demonstrations",[28] although The Morning Post reported "scoffs and jeers of enfranchised males who had posted themselves along the line of the route, and appeared to regard the occasion as suitable for the display of crude and vulgar jests".[32] Katharine Frye, who joined the march at Piccadilly Circus, recorded "not much joking at our expense and no roughness".[33][34] The Daily Mail--which supported women's suffrage—carried an eyewitness account, "How It Felt", by Constance Smedley of the Lyceum Club. Smedley described a divided reaction from the crowd: "that shared by the poorer class of men, namely, bitter resentment at the possibility of women getting any civic privilege they had not got; the other that of amusement at the fact of women wanting any serious thing ... badly enough to face the ordeal of a public demonstration".[35]

Approaching Trafalgar Square the march divided: representatives from the northern industrial towns broke off for an open-air meeting at Nelson's Column,[21] while the main march continued to Exeter Hall, for a meeting chaired by the Liberal politician Walter McLaren, whose wife, Eva McLaren, was one of the scheduled speakers.[33] Keir Hardie, leader of the Labour Party, told the meeting, to hissing from several Liberal women on the platform, that if women won the vote, it would be thanks to the "suffragettes' fighting brigade".[29][24] He spoke strongly in favour of the meeting's resolution, which was carried, that women be given the vote on the same basis as men,[36] and demanded a bill in the current parliamentary session.[23] At the Trafalgar Square meeting, Eva Gore-Booth referred to the "alienation of the Labour Party through the action of a certain section in the suffrage movement", according to The Observer, and asked the party "not to punish the millions of women workers" because of the actions of a small minority. When Hardie arrived from Exeter Hall, he expressed the hope that "no working man bring discredit on the class to which he belonged by denying to women those political rights which their fathers had won for them".[21]

Aftermath

Press reaction

The press coverage gave the movement "more publicity in a week", according to one commentator, "than it had enjoyed in the previous fifty years".[20] Lisa Tickner writes that the reporting was "inflected by the sympathy or otherwise of particular newspapers for the suffrage cause".[37] The Daily Mirror, neutral on the issue of women's suffrage, offered a large photospread,[38] and praised the crowd's diversity: "Never in the history of the suffragette movement has there been such a company as that which, representative of all classes, from a peeress to the humblest working woman, assembled to join in the procession."[39] The Times, an opponent of women's suffrage,[38] thought the event "remarkable as much for its representative character as for its size", describing the scenes and speeches in detail over 20 column inches.[40] The protesters had had to "run the gauntlet of much inconsiderate comment", according to the Daily Chronicle (supportive).[41] The pictorial journal The Sphere provided a montage of photographs under the headline "The Attack on Man's Supremacy".[31]

In its leading article, The Observer warned that "the vital civic duty and natural function of women ... is the healthy propagation of race", and that the aim of the movement was "nothing less than complete sex emancipation".[b] It was concerned that women were not ready for the vote: "If women had the vote tomorrow, how many would use it, still more, how many would be able to use it to any honest, intelligible purpose?" The movement should educate its own sex, rather than "seeking to confound men". The newspaper nevertheless welcomed that there had been "no attempts to bash policemen's helmets, to tear down the railings of the Park, to utter piercing war cries ..."[42] Likewise, The Daily News compared the event favourably to the actions of suffragettes: "Such a demonstration is far more likely to prove the reality of the demand for a vote than the practice of breaking up meetings held by Liberal Associations."[43] The Manchester Guardian agreed: "For those ... who, like ourselves, wish to see this movement – a great movement, as will one day be recognised – carried through in such a way as to win respect even where it cannot command agreement Saturday's demonstration was of good omen."[44]

Dickinson Bill

Four days after the march, the NUWSS executive met with the Parliamentary Committee for Women's Suffrage (founded 1893) to discuss a private member's bill.[45] On the same day, the suffragettes held their first "Women's Parliament" at Caxton Hall, after which 400 women marched toward the Commons to protest against the omission from the King's Speech, the day before, of a women's suffrage bill; over 60 were arrested, and 53 chose prison over a fine.[46]

On 26 February 1907 the Liberal MP for St Pancras North, Willoughby Dickinson, published the text of a bill proposing that women should have the vote subject to the same property qualification that applied to men. This would, it was estimated, enfranchise at least two million women.[c][non-primary source needed] (On the day the bill was published, the Cambridge Union passed by a small majority a motion "that this House would view with regret the extension of the franchise to women".)[47] Although the bill received strong backing from the suffragist movement, it was viewed more equivocally in the House of Commons, particularly by some Labour members who regarded it as giving more votes to the propertied classes, but doing nothing for working women.

- From numeral(s): This is a redirect from a title that includes the mathematical symbol of a number (or numbers) to an article with the word form of the number, or any other name of the number.

[non-primary source needed] On 8 March Dickinson introduced his Women's Enfranchisement Bill to the House of Commons for its second reading, with a plea that members should not be swayed by their distaste for militant actions;[48] the House of Commons "Ladies Gallery" was kept closed during the debate in case of protests by the WSPU.[49] The debate was inconclusive and the bill was "talked out" without a vote.[50] The NUWSS had worked hard for the bill and found the response insulting.[1]

Legacy

The Mud March was the largest-ever public demonstration at that time in support of woman's suffrage.[15] In her 1988 study of the suffrage campaign, Lisa Tickner observed that "modest and uncertain as it was by subsequent standards, [the march] established the precedent of large-scale processions, carefully ordered and publicised, accompanied by banners, bands and the colours of the participant societies."[51] Ray Strachey wrote:

In that year the vast majority of women still felt that there was something very dreadful in walking in procession through the streets; to do it was to be something of a martyr, and many of the demonstrators felt that they were risking their employments and endangering their reputations, besides facing a dreadful ordeal of ridicule and public shame. They walked, and nothing happened. The small boys in the streets and the gentlemen at the club windows laughed, but that was all. Crowds watched and wondered; and it was not so dreadful after all ... the idea of a public demonstration of faith in the Cause took root."[51]

Although it brought little by way of immediate progress on the parliamentary front, the march's significance was considerable. By embracing activism, the tactics of the NUWSS moved closer to those of the WSPU, at least in relation to the latter's non-violent activities.[24][non-primary source needed] The failure of Dickinson's bill brought about a further change in the NUWSS's strategy; it began to intervene directly in by-elections, on behalf of the candidate of any party who would publicly support women's suffrage. In 1907 the NUWSS supported the Conservatives in Hexham and Labour in Jarrow; where no suitable candidate was available they used the by-election to propagandise. This tactic met with sufficient success for the NUWSS to resolve that it would fight in all future by-elections.[52]

In the months and years that followed, the NUWSS and suffragettes held several peaceful demonstrations. On 13 June 1908 over 10,000 women took part in a London march organised by the NUWSS,[53] and on 21 June that year the suffragettes organised Women's Sunday in Hyde Park, attended by up to half a million.[2] During the NUWSS's Great Pilgrimage of April 1913, women marched from all over the country to London for a mass rally in Hyde Park, which 50,000 attended.[54] Their struggles were rewarded after the First World War, when women were partly enfranchised by the Representation of the People Act 1918, which granted the vote to women over 30 but to men over 21.[55] Full enfranchisement of all women over 21 came ten years later, when the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act of 1928 was passed by a Conservative government under Stanley Baldwin.[56]

The Mud March is featured in window No. 4 of the stained-glass Dearsley Windows in St Stephen's Hall in the Palace of Westminster. The window includes panels depicting, among other things, the formation of the NUWSS, WSPU and Women's Freedom League, the NUWSS's Great Pilgrimage, the force-feeding of suffragettes, the Cat and Mouse Act, and the death in 1913 of Emily Wilding Davison. The window was installed in 2002 as a memorial to the long and ultimately successful campaign for women's suffrage.[57][58]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b Hume 2016, p. 35.

- ^ a b Holten 2003, p. 46.

- ^ Hawksley 2017, p. 64.

- ^ "Founding of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies", UK Parliament.

- ^ Holton 2008.

- ^ Purvis 1998, p. 157.

- ^ Holton 2017.

- ^ Cowman 2010, p. 65.

- ^ Hume 2016, p. 30, citing Fawcett, Millicent (27 October 1906). "The Imprisoned Suffragists". The Times. p. 9.

- ^ a b Hume 2016, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Smith 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Hawksley 2017, p. 129.

- ^ Kelly 2004, pp. 333–334.

- ^ a b Tickner 1988, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Hume 2016, p. 34.

- ^ a b Caine 2004.

- ^ Crawford 2003, p. 104.

- ^ Park 2005, p. 125.

- ^ Hume 2016, p. 36.

- ^ a b Hill 2002, p. 154.

- ^ a b c The Observer, "Titled Demonstrators" ("Mr Hardie's Speech"), 10 February 1907.

- ^ "Pastscape: the former studio of the Artists Suffrage League". Historic England. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Procession and Speeches (extract from the Daily Mail, 11 February 1907)" (PDF). The National Archives. p. 37. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Pankhurst 1911, p. 135.

- ^ Fawcett 1925, p. 190.

- ^ Crawford 2003, pp. 30, 98, 159, 250.

- ^ Tickner 1988, p. 75, citing the Tribune.

- ^ a b The Observer, "Titled Demonstrators" ("The Procession"), 10 February 1907.

- ^ a b c Atkinson 2018, p. 60.

- ^ a b The Observer, "Titled Demonstrators", 10 February 1907.

- ^ a b The Sphere, 16 February 1907.

- ^ The Morning Post, 11 February 1907.

- ^ a b Crawford, Elizabeth. "Kate Frye's Suffrage Diary: The Mud March, 9 February 1907". Woman and her Sphere. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Crawford 2013, p. 29.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 337, citing the Daily Mail, 11 February 1907, p. 7.

- ^ Crawford 2003, p. 273.

- ^ Tickner 1988, p. 75.

- ^ a b Kelly 2004, p. 337.

- ^ Daily Mirror, 11 February 1907.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 338, citing The Times, 11 February 1907, p. 11.

- ^ Kelly 2004, p. 337, citing the Daily Chronicle, 11 February 1907, p. 6.

- ^ a b The Observer, "Lady Day", 10 February 1907.

- ^ Daily News, 11 February 1907.

- ^ Manchester Guardian, 11 February 1907.

- ^ Hume 2016, p. 34; "Parliamentary Committee for Women's Suffrage Archive", The National Archives.

- ^ "Talked Out! pamphlet", British Library; Purvis 2018, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Manchester Guardian, 27 February 1907.

- ^ Hume 2016, pp. 34–35.

- ^ "Gone grille: The removal of the Ladies' Gallery grilles", UK Vote 100, 23 August 2017.

- ^ Hume 2016, p. 35; Manchester Guardian, 9 March 1907.

- ^ a b Tickner 1988, p. 78.

- ^ Hume 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Hume 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Fara 2018, p. 67.

- ^ "Representation of the People Act 1918". UK Parliament. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ "1928 Equal Franchise Act". UK Parliament. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ "Baroness Massey discusses the Dearsley Window", UK Parliament Education Service, 22 April 2016.

- ^ "Dearsley Bequest Window" (PDF). Houses of Parliament. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

Sources

- Atkinson, Diane (2018). Rise Up, Women! The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Belchem, John (23 September 2004). "Hunt, Henry [called Orator Hunt]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) (subscription required) - Caine, Barbara (23 September 2004). "Strachey, Philippa [Pippa]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) (subscription required) - Cowman, Krista (2010). Women in British Politics, c. 1689–1979. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crawford, Elizabeth (2003). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866–1928. London: UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-135-43402-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crawford, Elizabeth (ed.) (2013). Campaigning for the vote: Kate Parry Frye's suffrage diary. London: Francis Boutle Publishers. ISBN 978-1-903-42775-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fara, Patricia (2018). A Lab of One's Own: Science and Suffrage in the First World War. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19879-498-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Foot, Paul (2012) [2005]. The Vote: How It Was Won and How It Was Undermined. London: Bookmark Publications. ISBN 978-1-909-02600-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hill, Leslie (2002). "Suffragettes Invented Performance Art". In de Gay, Jane; Goodman, Lizabeth (eds.). The Routledge Reader in Politics and Performance. London: Routledge. pp. 150–156. ISBN 978-1-134-68666-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holton, Sandra Stanley (2002). Suffrage Days: Stories from the women's suffrage movement. London and New York: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holten, Sandra Stanley (2003) [1986]. Feminism and Democracy: Women's Suffrage and Reform Politics in Britain, 1900–1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Howarth, Janet (4 October 2007). "Fawcett, Dame Millicent Garrett [née Millicent Garrett]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) (subscription required) - Hume, Leslie (2016) [1982]. The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies 1897–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31721-327-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kelly, Katherine E. (2004). "Seeing through Spectacles: The Woman Suffrage Movement and London Newspapers, 1906–13". European Journal of Women’s Studies. 11 (3): 327–353. doi:10.1177/1350506804044466.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lethbridge, Lucy (1 February 2018). "The women's march: how the Suffragettes changed Britain". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Herstein, Sheila R. (2012) [1988]. "Bodichon, Barbara Leigh Smith (1827–1891)". In Mitchell, Sally (ed.). Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. pp. 85–86.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Park, Sowon S. (February 2005). "Suffrage and Virginia Woolf: 'The Mass behind the Single Voice'". The Review of English Studies. 56 (223): 119–134. JSTOR 3661192.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pilkington, Colin (1999). The Politics Today Companion To the British Constitution. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-719-05303-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pugh, Martin (2000). The March of the Women: A Revisionist Analysis of the Campaign for Women's Suffrage, 1866–1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820775-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Purvis, June (2003). Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography. London and New York: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Purvis, June (2018). Christabel Pankhurst: A Biography. London and New York: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Harold L. (2014). The British Women's Suffrage Campaign 1866–1928: Revised 2nd Edition. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-86225-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tickner, Lisa (1988). The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907–14. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22680-245-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walker, Linda (23 September 2004). "Becker, Lydia Ernestine". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) (subscription required) - van Wingerden, Sophia A. (1999). The Women's Suffrage Movement in Britain, 1866–1928. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Primary sources

- "1928 Equal Franchise Act". UK Parliament. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "Caption: Distinguished leaders of the suffragettes". The Illustrated London News: 1. 16 February 1907.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Crawford, Elizabeth. "Kate Frye's Suffrage Diary: The Mud March, 9 February 1907". Woman and her Sphere. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- "Enfranchisement of Women: The Bill "Talked Out"". The Manchester Guardian. 9 March 1907. p. 9. (subscription required)

- Fawcett, Millicent Garrett (1911). Women's Suffrage: A Short History of a Great Movement. London: T. C. and E. C. Jack.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fawcett, Millicent Garrett (1925). What I Remember. New York: Putnam. OCLC 917605074.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Inaugural NUWSS meeting minutes and Notice of formation of the NUWSS (1897)". Central and Western Society for Women's Suffrage (courtesy of UK Parliament). 1897. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "Lady Day". The Observer. 10 February 1907. p. 6. (subscription required)

- "Leading Article". The Manchester Guardian. 11 February 1907. p. 6.

- Mill, Harriet Taylor (1868) [July 1851]. Enfranchisement of Women. London: Trübner & Co. Reprinted from the Westminster Review.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pankhurst, Sylvia (1911). The Suffragette: The History of the Women's Militant Suffrage Movement. New York: Sturgis & Walton Company. OCLC 66118841.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Procession and Speeches (extract from the Daily Mail, 11 February 1907)" (PDF). The National Archives. p. 37. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Richardson, R. J. (1971) [1840]. "Extract from 'The Rights of Woman' by R. J. Richardson". In Thompson, Dorothy (ed.). The Early Chartists. London and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Rights of women". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 14. House of Commons. 3 August 1832. col. 1086.

- "The Attack on Man's Supremacy". The Sphere: 138. 16 February 1907.

- "The Enfranchisement of Women (Letter)". The Manchester Guardian. 13 February 1907. p. 5. (subscription required)

- "The Women's March". The Daily Mirror. 11 February 1907. p. 4.

- "The Women's March". The Daily News. 11 February 1907. p. 6.

- "The Women Suffragists: A Muddy Promenade". The Morning Post. 11 February 1907. p. 5.

- "Titled Demonstrators". The Observer. 10 February 1907. p. 7. (subscription required)

- "Titled Demonstrators: Mr Hardie's Speech". The Observer. 10 February 1907. p. 7. (subscription required)

- "Titled Demonstrators: The Procession". The Observer. 10 February 1907. p. 7. (subscription required)