Euro: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 217.155.238.235 (talk) to last version by Zntrip |

|||

| Line 289: | Line 289: | ||

Too high an inflation rate postponed the entry of Lithuania as planned on [[1 January]] [[2007]]. Some of these currencies do not float against the euro, and a subset of those were unilaterally pegged with the euro before joining ERM II. See [[European Exchange Rate Mechanism]], [[currencies related to the euro]], and individual currency articles for more details. |

Too high an inflation rate postponed the entry of Lithuania as planned on [[1 January]] [[2007]]. Some of these currencies do not float against the euro, and a subset of those were unilaterally pegged with the euro before joining ERM II. See [[European Exchange Rate Mechanism]], [[currencies related to the euro]], and individual currency articles for more details. |

||

Originally, the Czech Republic aimed for entry into the ERM II in 2008 or 2009, but the current government has officially dropped the 2010 target date, saying it will clearly not meet the economic criteria. |

Originally, the Czech Republic aimed for entry into the ERM II in 2008 or 2009, but the current government has officially dropped the 2010 target date, saying it will clearly not meet the economic criteria. The new goal is 2012[[http://www.praguemonitor.com/en/29/czech_business/1766/]]. |

||

[[Cypriot euro coins|Cyprus]], [[Estonian euro coins|Estonia]], [[Latvian euro coins|Latvia]], [[Lithuanian euro coins|Lithuania]], [[Maltese euro coins|Malta]] and [[Slovak euro coins|Slovakia]] have already finalised the design for their respective coins' obverse sides. |

[[Cypriot euro coins|Cyprus]], [[Estonian euro coins|Estonia]], [[Latvian euro coins|Latvia]], [[Lithuanian euro coins|Lithuania]], [[Maltese euro coins|Malta]] and [[Slovak euro coins|Slovakia]] have already finalised the design for their respective coins' obverse sides. |

||

Revision as of 19:04, 22 February 2007

The euro (currency sign: €; banking code: EUR) is the official currency of the Eurozone, which consists of the European states of Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain. It is the single currency for more than 317 million Europeans. Including areas using currencies pegged to the euro, the euro affects more than 480 million people worldwide.[1] With more than €610 billion in circulation as of December 2006 (equivalent to US$802 billion at the exchange rates at the time), the euro has surpassed the U.S. dollar in terms of combined value of cash in circulation.[2]

While all EU member states are eligible to join if they comply with certain monetary requirements, the euro is not used in all of the European Union as not all EU members have adopted the currency. All nations which have recently joined the EU are pledged to adopt the euro in due course, but the United Kingdom and Denmark are under no such obligation.[3] Several small European states (The Vatican, Monaco and San Marino), although not EU members, have adopted the euro due to currency unions with member states. Andorra, Montenegro and Kosovo have adopted the euro unilaterally.

The euro was introduced to world financial markets as an accounting currency in 1999 and launched as physical coins and banknotes in 2002. It replaced the former ECU at a ratio of 1:1.

The euro is managed and administered by the Frankfurt-based European Central Bank (ECB) and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) (composed of the central banks of its member states). As an independent central bank, the ECB has sole authority to set monetary policy. The ESCB participates in the printing, minting and distribution of notes and coins in all member states, and the operation of the Eurozone payment systems.

Characteristics of the euro

Coins and banknotes

The euro is divided into 100 cent (sometimes referred to as eurocents). All euro coins (including the €2 commemorative coins) have a common side showing the denomination (value) with the EU-countries in the background and a national side showing an image specifically chosen by the country that issued the coin. Euro coins from any country may be freely used in any nation which has adopted the euro.

The euro coins are €2, €1, 50c, 20c, 10c, 5c, 2c and 1c. The two smallest denominations are no longer struck (except for collectors) in the Netherlands or Finland, where cash transactions are rounded to the nearest five cents, but they remain legal tender there. Note that there is no plural for the European Cent, 1 cent, 2 cent and so on.

Commemorative coins of various other denominations, not intended for circulation, have been issued. They are legal tender only in the nation which issued them. In addition, members have from time to time replaced the national side of the two euro coin with a commemorative design--as Greece did for the 2004 Summer Olympics. Such coins are legal tender throughout the eurozone.

All euro banknotes have a common design for each denomination on both sides. Notes are issued in €500, €200, €100, €50, €20, €10, €5. Some of the higher denominations, such as €500 and €200, are not issued in a few countries, though they remain legal tender throughout the eurozone. The design for each of them has a common theme of European architecture in various artistic periods. The front (or recto) of the note features windows or gateways while the back (or verso) has bridges. Care has been taken so that the architectural examples do not represent any actual existing monument, so as not to induce jealousy and controversy in the choice of which monument should be depicted

Payments clearing, electronic funds transfer

The ECB has set up a clearing system, TARGET, for large euro transactions.[4]

All intra-Eurozone transfers shall cost the same as a domestic one. This is true for retail payments, although several ECB payment methods can be used. Credit/debit card charging and ATM withdrawals within the Eurozone are also charged as if they were domestic. The ECB has not standardized paper-based payment orders, such as cheques; these are still domestic-based.

The currency sign €

A special euro currency sign (€) was designed after a public survey had narrowed the original ten proposals down to two. The European Commission then chose the final design. The eventual winner was a design created by the Belgian Alain Billiet. The official story of the design history of the euro sign is disputed by Arthur Eisenmenger, a former chief graphic designer for the EEC, who claims to have created it as a generic symbol of Europe.

The glyph is (according to the European Commission) "a combination of the Greek epsilon, as a sign of the weight of European civilization; an E for Europe; and the parallel lines crossing through standing for the stability of the euro".

The European Commission also specified a euro logo with exact proportions and foreground/background colour tones.[5] Although some font designers simply copied the exact shape of this logo as the euro sign in their fonts, most designed their own variants, often based upon the capital letter C in the respective font so that currency signs have the same width as Arabic numerals.[6]

Placement of the currency sign varies from nation to nation. There are no official standards on where to place the euro symbol.[7] Generally, people in the euro countries have kept the placement of their former currencies.[citation needed]

Another advantage to the final chosen symbol is that it is easily created on the huge worldwide installed base of typewriters, by typing a capital 'C', backspacing and overstriking it with the equal ('=') sign.

Economic and Monetary Union

Template:Life in the European Union

History (1990-2007)

The euro was established by the provisions in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty on European Union that was used to establish an economic and monetary union. In order to participate in the new currency, member states had to meet strict criteria such as a budget deficit of less than three per cent of their GDP, a debt ratio of less than sixty per cent of GDP, low inflation, and interest rates close to the EU average.

Economists that helped create or contributed to the euro include Robert Mundell, Wim Duisenberg, Robert Tollison, Neil Dowling and Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa. (For macro-economic theory, see below.)

Due to differences in national conventions for rounding and significant digits, all conversion between the national currencies had to be carried out using the process of triangulation via the euro. The definitive values in euro of these subdivisions (which represent the exchange rates at which the currency entered the euro) are shown at right.

The rates were determined by the Council of the European Union, based on a recommendation from the European Commission based on the market rates on 31 December 1998, so that one ECU (European Currency Unit) would equal one euro. (The European Currency Unit was an accounting unit used by the EU, based on the currencies of the member states; it was not a currency in its own right.) Council Regulation 2866/98 (EC), of 31 December 1998, set these rates. They could not be set earlier, because the ECU depended on the closing exchange rate of the non-euro currencies (principally the pound sterling) that day.

| Currency | Abbr. | Rate | Fixed on | EMU III |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATS | 13.7603 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| BEF | 40.3399 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| NLG | 2.20371 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| FIM | 5.94573 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| FRF | 6.55957 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| DEM | 1.95583 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| IEP | 0.787564 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| ITL | 1936.27 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| LUF | 40.3399 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| PTE | 200.482 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| ESP | 166.386 | 31/12/1998 | 1999 | |

| GRD | 340.750[8] | 19/06/2000 | 2001 | |

| SIT | 239.640[9] | 11/07/2006 | 2007 |

The procedure used to fix the irrevocable conversion rate between the drachma and the euro was different, since the euro by then was already two years old. While the conversion rates for the initial eleven currencies were determined only hours before the euro was introduced, the conversion rate for the Greek drachma was fixed several months beforehand, in Council Regulation 1478/2000 (EC), of 19 June 2000.

The currency was introduced in non-physical form (travellers' cheques, electronic transfers, banking, etc.) at midnight on 1 January 1999, when the national currencies of participating countries (the Eurozone) ceased to exist independently in that their exchange rates were locked at fixed rates against each other, effectively making them mere non-decimal subdivisions of the euro. The euro thus became the successor to the European Currency Unit (ECU). The notes and coins for the old currencies, however, continued to be used as legal tender until new notes and coins were introduced on 1 January 2002.

The changeover period during which the former currencies' notes and coins were exchanged for those of the euro lasted about two months, until 28 February 2002. The official date on which the national currencies ceased to be legal tender varied from member state to member state. The earliest date was in Germany; the Mark officially ceased to be legal tender on 31 December 2001, though the exchange period lasted two months. The final date was 28 February 2002, by which all national currencies ceased to be legal tender in their respective member states. However, even after the official date, they continued to be accepted by national central banks for several years up to forever in Austria, Germany, Ireland, and Spain. The earliest coins to become non-convertible were the Portuguese escudos, which ceased to have monetary value after 31 December 2002, although banknotes remain exchangeable until 2022.

On 1 January 2007, Slovenia joined the eurozone.

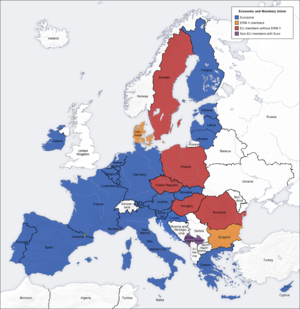

Current Eurozone (2007)

- The euro is the sole currency in Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain. These 13 countries together are frequently referred to as the Eurozone or the euro area, or more informally "euroland" or the "eurogroup". The euro is also the legal currency of the French overseas territories of French Guiana, Réunion, Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, Guadeloupe, Martinique and Mayotte.

- By virtue of some bilateral agreements the European microstates of Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City mint their own euro coins on behalf of the European Central Bank. They are, however, severely limited in the total value of coins they may issue.

- Andorra, Montenegro and Kosovo adopted the foreign euro as their legal currency for movement of capital and payments without participation in the ESCB or the right to mint coins. Andorra is in the process of entering a monetary agreement similar to Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City.

Future prospects (2008-)

Pre-2004 EU members

From Greece's participation in 2001 until the EU enlargement in 2004, Denmark, Sweden and the United Kingdom were the only EU member states outside the monetary union. The situation for the three older member states also looks different from that of the newer EU members; all three have no clear roadmap for adopting the euro:

- Sweden: According to the 1995 accession treaty, approved by referendum, Sweden is required to join the euro and therefore must convert to the euro at some point. Notwithstanding this, on 14 September 2003, a Swedish referendum was held on the euro, the result of which was 56% against adopting the common currency versus 42% in favour. The Swedish government has argued that staying outside the euro is legal since one of the requirements for Eurozone membership is a prior two-year membership of the ERM II; by simply choosing to stay outside the exchange rate mechanism, the Swedish government is provided a formal loophole avoiding the requirement of adopting the euro. Some of Sweden's major parties continue to believe that it would be in the national interest to join, but they have all pledged to abide by the result of the referendum for the time being and show no interest in raising the issue. An optimistic timetable is to have a new referendum in 2012 and adopting the euro in 2015. Faster than that is not likely, but slower is more than likely.

- The United Kingdom's eurosceptics believe the single currency is merely a stepping stone to the formation of a unified European superstate, and that removing the UK's ability to set its own interest rates will have detrimental effects on its economy. Others in the UK, usually joined by eurosceptics, advance several economic arguments against membership: the most cited concerns the large unfunded pension liabilities of many continental European governments—unlike in the UK—which could, with an ageing population, depress the currency in the future against the UK's interests. An opposing view is that, intra-European exports make up to 50% of the UK's total and a single currency would enhance the Single Market by removing currency risk. Although, financial derivatives are becoming more accessible to small UK businesses thereby allowing businesses to offset currency risk. An interesting parallel can be seen in the 19th century discussions concerning the possibility of the United Kingdom joining the Latin Monetary Union.[10] Some British people simply want sterling as a currency because it is part of UK heritage. The UK government has set five economic tests that must be passed before it can recommend that the UK join the euro; however, given the relatively subjective nature of these tests it seems unlikely they would be held to be fulfilled whilst public opinion remains so strongly against participation. In November 1999, in preparation for the introduction of the euro notes and coins across the eurozone, the European Central Bank announced a total ban on the issuing of banknotes by entities that were not National Central Banks ('Legal Protection of Banknotes in the European Union Member States'). Unless a derogation could be negotiated by the UK as a condition of entering the eurozone, a change from Sterling to the euro would mean an immediate end to the circulation of Scottish and Northern Irish banknotes (see sterling banknotes). The ECB has also stated that even with notes issued by a central bank, there is 'no room for exclusively national arrangements'—all notes must be produced to the central designs. National variation is allowed in the design of euro coins, and it is possible that the Royal Mint could continue to include the symbols of the home nations on the British designed coinage, although this would have to be included in place of the Queen's portrait. The position of the Crown Dependencies is less clear. The European Union has so far strongly resisted attempts to issue euro-equivalent notes by non-EU states unless steps are taken to enter into a suitable monetary agreement, including the adoption of EU banking and finance regulations (see Andorran euro coins).

- Denmark negotiated a number of opt-out clauses from the Maastricht treaty after it had been rejected in a first referendum. On 28 September 2000, another referendum was held in Denmark regarding the euro resulting in a 53.2% vote against joining. However, Danish politicians have suggested that debate on abolishing the four opt-out clauses may possibly be re-opened. In addition, Denmark has pegged its krone to the euro (€1 = DKr7.460,38 ± 2.25%) as the krone remains in the ERM.

Post-2004 EU members

As of 2007, 11 new EU member states had a currency other than the euro; however, all of these countries are required by their Accession Treaties to join the euro. Some of the following countries have already joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, ERM II. They and the others have set themselves the goal to join the euro (EMU III) as follows:

| Currency | Abbr. | Rate | Conv goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP | 0.585274 | 2008-01-01 | |

| MTL | 0.429300 | 2008-01-01 | |

| SKK | 38.4550 | 2009-01-01 | |

| LTL | 3.45280 | 2010-01-01 | |

| BGN | 1.95583[11] | 2010-01-01 | |

| EEK | 15.6466 | 2010-01-01 | |

| LVL | 0.702804 | 2011– | |

| CZK | — | 2013- | |

| PLN | — | 2011– | |

| RON | — | 2014-01-01 | |

| HUF | — | 2011– |

- 1 January 2008 for Cyprus and Malta

- 1 January 2009 for Slovakia[12]

- 1 January 2010 for Lithuania,[13] Bulgaria[14][15][16] and Estonia.[17]

- 2011 or later for Hungary, Latvia,[18] Poland and Romania

Too high an inflation rate postponed the entry of Lithuania as planned on 1 January 2007. Some of these currencies do not float against the euro, and a subset of those were unilaterally pegged with the euro before joining ERM II. See European Exchange Rate Mechanism, currencies related to the euro, and individual currency articles for more details.

Originally, the Czech Republic aimed for entry into the ERM II in 2008 or 2009, but the current government has officially dropped the 2010 target date, saying it will clearly not meet the economic criteria. The new goal is 2012[[2]].

Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta and Slovakia have already finalised the design for their respective coins' obverse sides.

Public opinion on secession from the euro

Although the failure of the European Constitution to be ratified would have no direct impact on the status of the euro, some debate regarding the euro arose after the negative outcome of the French and Dutch referenda in mid 2005.

- A poll by Stern magazine released 1 June 2005 found that 56% of Germans would favour a return to the Mark.[19]

- Members of the Northern League northern Italian separatist political party have discussed calling a referendum to return Italy to the lira.[20]

- Members of the right-wing Movement for France political party have proposed holding a referendum to return France to the franc.[21]

- In contrast to Germany, a poll in Austria on 7 June 2005 showed the overwhelming support of the euro as 73% of the sample said they preferred to keep the common currency with only 21% in favour of returning to the old currency, the Schilling.[22]

- Soon after these suggestions were made, the European Commission issued a statement denying any possibility of this, stating "the euro is here to stay".

More recently, in April 2006, after the Italian elections, the subject once again came up. Again, the EU strongly refuted this, calling the suggestion "impossible".

Economics of the euro

Optimal currency areas

In economic theory the degree of fulfilment of the following four criteria indicates whether an area is optimal for a monetary union. These criteria are often called the optimum currency area (OCA) criteria and are generally accepted as a reasonable metric to establish an OCA although they are not exhaustive and far from absolute. There are three economic criteria (labour and capital mobility, product diversification, and openness) and one political criterion (fiscal transfers). Since establishing a single currency over a region necessitates surrendering the ability to tailor monetary policy to specific local conditions, these four characteristics measure the ability of the economy to smooth local economic movements in the absence of monetary policy.

- Robert A. Mundell formulated the idea that perfect capital and labour mobility would mitigate the adverse consequences of asymmetric shocks in a currency area. While capital is quite mobile in the Eurozone, labour mobility is relatively low, especially when compared to the U.S. and Japan.

- Peter Kenen formulated the idea that widely diversified production and export structures that are similar between the areas that form the currency area lower the effect and probability of asymmetric shocks. The Eurozone scores quite well on this criterion, and monetary integration seems to further improve the diversification of production structures.

- Ronald McKinnon formulated the idea that areas which are very open to trade and trade heavily with each other form an optimum currency area. This is because the high trade intensity will lower the significance of the distinction between domestic and foreign goods as competition will equalize the prices of most goods, independently of exchange rates. The Eurozone members trade heavily with each other (intra-European trade is greater than international trade), and all evidence so far seems to indicate that the monetary union has at least doubled trade between members.

- The term "fiscal transfers" refers to the transfer of money between areas. Regions that are economically worse off or suffer from negative economic shocks receive money, creating a counter cyclical effect that lowers the price, wage, and unemployment differentials between regions. Theoretically, Europe has no-bail out clause in the Stability and Growth Pact, meaning that fiscal transfers are not allowed, but it's impossible to know what will happen in practice.

So while Europe scores well on some of the measures characterizing an OCA, it has lower labour mobility than the United States and similarly cannot rely on Fiscal federalism to smooth out regional economic disturbances.But for putting into perspective ,some economists have argued ,that the United States, really consists of two optimal currency areas, one in the western half and one in the eastern half.[3]

Transaction costs and risks

The most obvious benefit of adopting a single currency is removing from trade the cost of exchanging currency, theoretically allowing businesses and individuals to consummate previously unprofitable trades. On the consumer side, banks in the Eurozone must charge the same for intra-member cross-border transactions as purely domestic transactions for electronic payments (e.g. credit cards, debit cards and cash machine withdrawals).

The absence of distinct currencies also removes exchange rate risks. The risk of unanticipated exchange rate movement has always added an additional risk or uncertainty for companies or individuals looking to invest or trade outside their own currency zones. Companies that hedge against this risk will no longer need to shoulder this additional cost. The reduction in risk is particularly important for countries whose currencies have traditionally fluctuated a great deal, particularly the Mediterranean nations.

Financial markets on the continent are expected to be far more liquid and flexible than they were in the past. The reduction in cross-border transaction costs will allow larger banking firms to provide a wider array of banking services that can compete across and beyond the Eurozone.

Price parity

Another effect of the common European currency is that differences in prices — in particular in price levels — should decrease because of the 'law of one price'. Differences in prices can trigger arbitrage, i.e. speculative trade in a commodity between countries purely to exploit the price differential, which will tend to equalise prices across the euro area. Similarly, price transparency across borders should help consumers find lower cost goods or services. In reality, the effects of the euro over the level of the prices in Europe are disputable. Many citizens cite the strong increase in prices in the years after the introduction of the euro, although numerous empirical studies have failed to find much real evidence of this.[citation needed] It is speculated that the reason for this perception is that the prices of small, everyday items were rounded up significantly. For example, a cup of coffee that once cost two German Mark might now cost €1.50 or even €2.00 - a 50-100% increase. At the same time, a large appliance or rent payment rounded up to the next obvious euro level would be a negligible proportional increase. The fact that the prices people see every day were affected more strongly might explain why so many people perceive the "euro effect" as being significant, while official studies — which look at the breadth of expenditures, in proportion — would downplay it.

Macroeconomic stability

Low levels of inflation are the hallmark of stable and modern economies. Because a high level of inflation acts as a highly regressive tax (seigniorage) and theoretically discourages investment, it is generally viewed as undesirable. In spite of the downside, many countries have been unable or unwilling to deal with serious inflationary pressures. Some countries have successfully contained by establishing largely independent central banks. One such bank was the Bundesbank in Germany; as the European Central Bank is modelled on the Bundesbank, it is independent of the pressures of national governments and has a mandate to keep inflationary pressures low. Member countries join the bank to credibly commit to lower inflation, hoping to enjoy the macroeconomic stability associated with low levels of expected inflation. The ECB (unlike the Federal Reserve in the United States of America) does not have a second objective to sustain growth and employment.

National and corporate bonds denominated in euro are significantly more liquid and have lower interest rates than was historically the case when denominated in legacy currency[citation needed]. While increased liquidity may lower the nominal interest rate on the bond, denominating the bond in a currency with low levels of inflation arguably plays a much larger role. A credible commitment to low levels of inflation and a stable reduces the risk that the value of the debt will be eroded by higher levels of inflation or default in the future, allowing debt to be issued at a lower nominal interest rate.

A 2007 report released by Europol claims success in combatting counterfeiting of Euro banknotes and states: "Figures released by the ECB confirm that the amount of counterfeit Euro banknotes identified as being in circulation remained stable in 2006 and even decreased slightly when compared with 2005."[23] The report further conveys Europol's awareness of the importance of curbing counterfeiting while at the same time noting that the estimated number of counterfeit Euro notes in circulation is relatively low.

A new reserve currency

The euro is widely perceived to be one of two, or perhaps three, major global reserve currencies, making inroads on the widely used U.S. dollar (USD), which has historically been used by commercial and central banks world-wide as a stable reserve on which to ensure their liquidity and facilitate international transactions. A currency is attractive for foreign transactions when it demonstrates a proven track record of stability, a well-developed financial market to dispose of the currency in, and proven acceptability to others. While the euro has made substantial progress toward achieving these features, there are a few challenges that undermine the ascension of the euro as a major reserve currency. Persistent excessive budget deficits of member nations, economically weak new members, and serious questions regarding expansion threaten the place of the new currency.

As a new reserve currency, government sponsoring the euro do receive some substantial benefits. Since money is effectively an interest free loan to the government by the holder of the currency — foreign reserves act as subsidy to the country minting the currency (see Seigniorage).

Criticism

Some European nationalist parties oppose the euro as part of a more general opposition to the principle of a European union. A significant group of these include the members of the Independence and Democracy bloc in the European Parliament. Additionally the Green Party of England and Wales is opposed for anti-globalisation reasons but the rest of the European Green Party bloc in the European Parliament do not share their stance.

In their view, the countries that participate in the EMU have surrendered their sovereign abilities to conduct monetary policy. The European Central Bank is required to pursue a policy that might be at odds with national interests and there is no guarantee of extra-national assistance from their more fortunate neighbours should local conditions necessitate some sort of economic stimulus package. Many critics of the EMU believe the benefits to joining the organization are outweighed by the loss of sovereignty over local policy that accompanies membership.

The Euro is underpinned by the Stability and Growth Pact, which is designed to ensure even fiscal policy across the Eurozone. The SGP has been criticized for removing the ability of national governments to stimulate their own economies, in the only way left to them now that monetary policy is determined supranationally. The widespread failure to observe the SGP, and its inherent problems have led to minor reforms, and further reforms are likely.

Euro exchange rate

Flexible exchange rates

The ECB targets interest rates rather than exchange rates and in general does not intervene on the foreign exchange rate markets, because of the implications of the Mundell-Fleming Model, being the fact that a central bank can not maintain an interest rate target and an exchange rate target simultaneously, as increasing the money supply would result in a depreciation of the currency. In the years following the Single European Act, the EU has liberalized its capital markets, and as the ECB has chosen for monetary autonomy, the exchange rate regime of the euro is flexible, or floating. This explains why the exchange rate of the euro vis-à-vis other currencies is characterized by strong fluctuations. Most notable are the fluctuations of the euro vs. the U.S. dollar, another freely floating currency. However this focus on the dollar-euro parity is partly subjective. It is taken as a reference because the European authorities expect the euro to compete with the dollar. The effect of this selective reference is misleading, as it give to the observers the impression that a rise in the value of the euro vs the dollar is the effect of an increased global strength of the euro, while it may be the effect of an intrinsic weakening of the dollar itself.

Against other major currencies

Green: in Jan-1999: €1 = 1.18 USD ; in May-2006: €1 = 1.28 USD

Red: in Jan-1999: €1 = 133 JPY ; in May-2006: €1 = 144 JPY

Blue: in Jan-1999: €1 = 0.71 GBP ; in May-2006: €1 = 0.68 GBP

After the introduction of the euro, its exchange rate against other currencies, especially the U.S. dollar, declined heavily. At its introduction in 1999, the euro was traded at 1.18 US$/€; on 26 October 2000, it fell to an all time low of 0.8228 $/€. It then began what at the time was thought to be a recovery; by the beginning of 2001 it had risen to nearly $0.96. It declined again, although less than previously, reaching a low of 0.8344 $/€ on 6 July 2001 before commencing a steady appreciation. The two currencies reached parity on 15 July 2002, and by the end of 2002 the euro had reached 1.04 $/€ as it climbed further.

On 23 May 2003, the euro surpassed its initial (1.18 $/€) trading value for the first time. At the end of 2004, it had reached a peak of $1.3668 per euro (0.7316 €/$) as the U.S. dollar fell against all major currencies, fueled by the so called twin deficit of the US accounts. Although the US trade imbalances are heavily against East Asia rather than Europe, East Asia's reluctance to let their currencies rise has led to the euro's rising in its place. However, the dollar recovered in 2005, rising to 1.18 $/€ (0.85 €/$) in July 2005 (and stable throughout the second half of 2005). The fast increase in U.S. interest rates during 2005 had much to do with this trend.

By early December 2006 the dollar fell below €0.75 hitting a low of 0.7495 €/$ (=1.3340 $/€), a little more than 3 cents away from a record low set in late 2004.

- Current and historical exchange rates against 29 other currencies (European Central Bank)

- Current dollar/euro exchange rates (BBC)

- Historical exchange rate from 1971 until now

Currencies pegged to the euro

There are a number of foreign currencies that were pegged to a European currency and are now currencies related to the euro: the Cape Verdean escudo, the Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the Bulgarian lev, the CFP franc, the CFA franc and the Comorian franc.

In total, the euro is the official currency in 16 states inside the European Union, 2 state/territory outside the European Union. In addition, 25 states and territories have currencies that are directly pegged to the euro including 14 countries in mainland Africa, 4 EU members that will ultimately join the euro, 3 French Pacific territories, 2 African island countries and 2 Balkan countries.

The euro as a major international reserve currency

Since its introduction, the euro is the second most widely-held international reserve currency after the US dollar. The euro inherited this status from the German Mark, and since its introduction, has increased its standing considerably, mostly at the expense of the dollar.

| 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1995 | 1990 | 1985 | 1980 | 1975 | 1970 | 1965 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US dollar | 58.41% | 58.52% | 58.80% | 58.92% | 60.75% | 61.76% | 62.73% | 65.36% | 65.73% | 65.14% | 61.24% | 61.47% | 62.59% | 62.14% | 62.05% | 63.77% | 63.87% | 65.04% | 66.51% | 65.51% | 65.45% | 66.50% | 71.51% | 71.13% | 58.96% | 47.14% | 56.66% | 57.88% | 84.61% | 84.85% | 72.93% |

| Euro (until 1999—ECU) | 19.98% | 20.40% | 20.59% | 21.29% | 20.59% | 20.67% | 20.17% | 19.14% | 19.14% | 21.20% | 24.20% | 24.05% | 24.40% | 25.71% | 27.66% | 26.21% | 26.14% | 24.99% | 23.89% | 24.68% | 25.03% | 23.65% | 19.18% | 18.29% | 8.53% | 11.64% | 14.00% | 17.46% | |||

| Japanese yen | 5.70% | 5.51% | 5.52% | 6.03% | 5.87% | 5.19% | 4.90% | 3.95% | 3.75% | 3.54% | 3.82% | 4.09% | 3.61% | 3.66% | 2.90% | 3.47% | 3.18% | 3.46% | 3.96% | 4.28% | 4.42% | 4.94% | 5.04% | 6.06% | 6.77% | 9.40% | 8.69% | 3.93% | 0.61% | ||

| Pound sterling | 4.84% | 4.92% | 4.81% | 4.73% | 4.64% | 4.43% | 4.54% | 4.35% | 4.71% | 3.70% | 3.98% | 4.04% | 3.83% | 3.94% | 4.25% | 4.22% | 4.82% | 4.52% | 3.75% | 3.49% | 2.86% | 2.92% | 2.70% | 2.75% | 2.11% | 2.39% | 2.03% | 2.40% | 3.42% | 11.36% | 25.76% |

| Canadian dollar | 2.58% | 2.38% | 2.38% | 2.08% | 1.86% | 1.84% | 2.03% | 1.94% | 1.77% | 1.75% | 1.83% | 1.42% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese renminbi | 2.29% | 2.61% | 2.80% | 2.29% | 1.94% | 1.89% | 1.23% | 1.08% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australian dollar | 2.11% | 1.97% | 1.84% | 1.83% | 1.70% | 1.63% | 1.80% | 1.69% | 1.77% | 1.59% | 1.82% | 1.46% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Swiss franc | 0.23% | 0.23% | 0.17% | 0.17% | 0.15% | 0.14% | 0.18% | 0.16% | 0.27% | 0.24% | 0.27% | 0.21% | 0.08% | 0.13% | 0.12% | 0.14% | 0.16% | 0.17% | 0.15% | 0.17% | 0.23% | 0.41% | 0.25% | 0.27% | 0.33% | 0.84% | 1.40% | 2.25% | 1.34% | 0.61% | |

| Deutsche Mark | 15.75% | 19.83% | 13.74% | 12.92% | 6.62% | 1.94% | 0.17% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| French franc | 2.35% | 2.71% | 0.58% | 0.97% | 1.16% | 0.73% | 1.11% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dutch guilder | 0.32% | 1.15% | 0.78% | 0.89% | 0.66% | 0.08% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other currencies | 3.87% | 3.48% | 3.09% | 2.65% | 2.51% | 2.45% | 2.43% | 2.33% | 2.86% | 2.83% | 2.84% | 3.26% | 5.49% | 4.43% | 3.04% | 2.20% | 1.83% | 1.81% | 1.74% | 1.87% | 2.01% | 1.58% | 1.31% | 1.49% | 4.87% | 4.89% | 2.13% | 1.29% | 1.58% | 0.43% | 0.03% |

| Source: World Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves. International Monetary Fund. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current EUR exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK RUB |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK RUB |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK RUB |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK RUB |

Name and linguistic issues

Several linguistic issues have arisen in relation to the spelling of the words euro and cent in the many languages of the member states of the European Union, as well as in relation to grammar and the formation of plurals. However, in each country but Greece, which uses λεπτό (lepto, Singular) and λεπτά (lepta, Plural) on its coins, the form "cent" is officially required to be used in legislation in both the singular and in the plural. Immutable word formations have been encouraged by the European Commission in usage with official EU legislation (originally in order to ensure uniform presentation on the banknotes), but the "unofficial" practice concerning the mutability (or not) of the words differs between the member states and their languages. The subject has led to much debate and controversy.

See also

Euro related

- Currency bill tracking

- Economy of the European Union and Economy of Europe.

- Eonia, an effective overnight reference rate for the euro.

- Euribor, a benchmark for money market in the Eurozone.

- European System of Central Banks

- European Central Bank

- Latin Monetary Union (1865–1927)

- Scandinavian Monetary Union

Other common currencies

- Amero, a proposed North American currency union.

- Eco, a planned West African currency to be used by 5 or 6 nations by 2009.

- Khaleeji, a planned common currency of the 6 nations of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf to be produced by 2010

Notes

- ^ Number is a sum of estimated populations (as stated in their respective articles) of: all eurozone members; all users of euro not part of eurozone (whether officially agreed upon or not); all areas which use a currency pegged to the euro, and only the euro.

- ^ http://www.ft.com/cms/s/18338034-95ec-11db-9976-0000779e2340.html

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/euro/transition/transition_main_en.htm

- ^ http://www.ecb.int/paym/target/html/index.en.html

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/euro/notes_and_coins/symbol_en.htm

- ^ http://www.fontshop.com/virtual/features/eng/fontmag/002/02_euro/index.htm

- ^ http://www.delidn.ec.europa.eu/en/references/references_5.htm#Q12

- ^ Greece failed to meet the criteria for joining initially, so it did not join the common currency on 1 January 1999. It was admitted two years later, on 1 January 2001, with a Greek drachma (GRD) exchange rate of 340.750.

- ^ The final exchange rate was finalised on 2006-07-11. However, the finalised rate was not formally effective before the Tolar was succeeded by the Euro on 2007-01-01.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Bulgaria is not officially part of ERM II as of 7 January 2007. But as the Bulgarian lev exchange rate is fixed to the rate of German mark (and thus to the Euro) country is included in the list.

- ^ Government approved the National Euro Changeover Plan Bank of Slovakia, 2005-07-07

- ^ Adoption of the Euro in Lithuania Bank of Lithuania, retrieved: 2007-02-03

- ^ "Agreement between the Council of Ministers and the Bulgarian National Bank on the introduction of the Euro in the Republic of Bulgaria" (PDF). Bulgarian National Bank. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ^ "Правим първи стъпки за еврото" (in Bulgarian). Pari. 2006-12-28. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ^ "Bulgaria may introduce the Euro in 2010". BNR Radio Bulgaria. 2006-12-04. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ^ Non, nein, no: Europe turns negative on the euro, The Times, 2006-12-31, accessed on 2006-12-31

- ^ Latvia might adopt Euro between 2010 and 2012 - Minister, Forbes, 2006-12-04, accessed on 2007-01-01

- ^ http://www.stern.de/presse/vorab/?id=541124&q=eichel%20category:presse

- ^ http://washingtontimes.com/world/20050614-114629-8803r.htm

- ^ http://news.scotsman.com/international.cfm?id=664902005

- ^ vienna.at

- ^ http://www.europol.europa.eu/index.asp?page=news&news=pr070112.htm

References

- Baldwin, Richard and Charles Wyplosz, The Economics of European Integration, New York: McGraw Hill, 2004.

- European Commission, High Level Task Force on Skills and Mobility - Final Report, 14 December 2001.

External links

- European Central Bank Official Site

- European Banking Federation Official Site

- The Euro: Our Currency Official EU Site

- Dollar/Euro-Chart

- Purchasing power of the Euro abroad - Federal Statistical Office Germany

- The English Style Guide of the European Commission's Directorate-General for Translation. See section 20.7 for the recommendation that in all non-legal texts, "especially documents intended for the general public, use the natural plurals 'euros' and 'cents'."

- EU warning for euro hopefuls, BBC news story about EU report to would-be Eurozone members

- www.eurobilltracker.com Follow the Euro Banknotes during their journey!

Articles

- A critical view on "Britain and the Euro"

- A critical view on "inflationary euro"

- European Monetary Union and the euro

- EU and EMU information including coin and banknote images

- Britain and European Monetary Union

- Report on the Names of the European Currency in Maltese (PDF) (Il-Kunsill Nazzjonali ta' l-Ilsien Malti including "The plural of ewro is ewro" as well as a discussion on what the words for "euro" and "cent" should be in Maltese)

- The euro and standardisation (Michael Everson; including "The plural of euro is euros!" as well as a discussion on what the words for "euro" and "cent" should be in Irish)

- A brief commentary by one of the economists instrumental in creating the euro

- Introduction to the euro

- The euro page from the Economist (many articles require a subscription)

- The euro and the History of Previous Currency Unions, YoursDaily.com

- The Euro and Its Antecedents by Jerry Mushin, Victoria University of Wellington