2022 Kharkiv counteroffensive: Difference between revisions

→Breakthrough and exploitation: Let's hope the Russians don't return and re-re-repaint it, because then Ukr will have to re-re-re-repaint it |

Fixed misinformation Tags: Reverted Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| conflict = 2022 Ukrainian Kharkiv counteroffensive |

| conflict = 2022 Ukrainian Kharkiv counteroffensive |

||

| place = [[Kharkiv Oblast]], [[Ukraine]] |

| place = [[Kharkiv Oblast]], [[Ukraine]] |

||

| date = |

| date = 6–13 September 2022<br>(7 days) |

||

| partof = the [[2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine]], the [[Northeastern Ukraine offensive]] and the [[Eastern Ukraine offensive]] |

| partof = the [[2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine]], the [[Northeastern Ukraine offensive]] and the [[Eastern Ukraine offensive]] |

||

| image = {{CSS image crop |

| image = {{CSS image crop |

||

Revision as of 10:27, 15 September 2022

A request that this article title be changed to 2022 Ukrainian eastern counteroffensive is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (September 2022) |

| 2022 Ukrainian Kharkiv counteroffensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Northeastern Ukraine offensive and the Eastern Ukraine offensive | |||||||

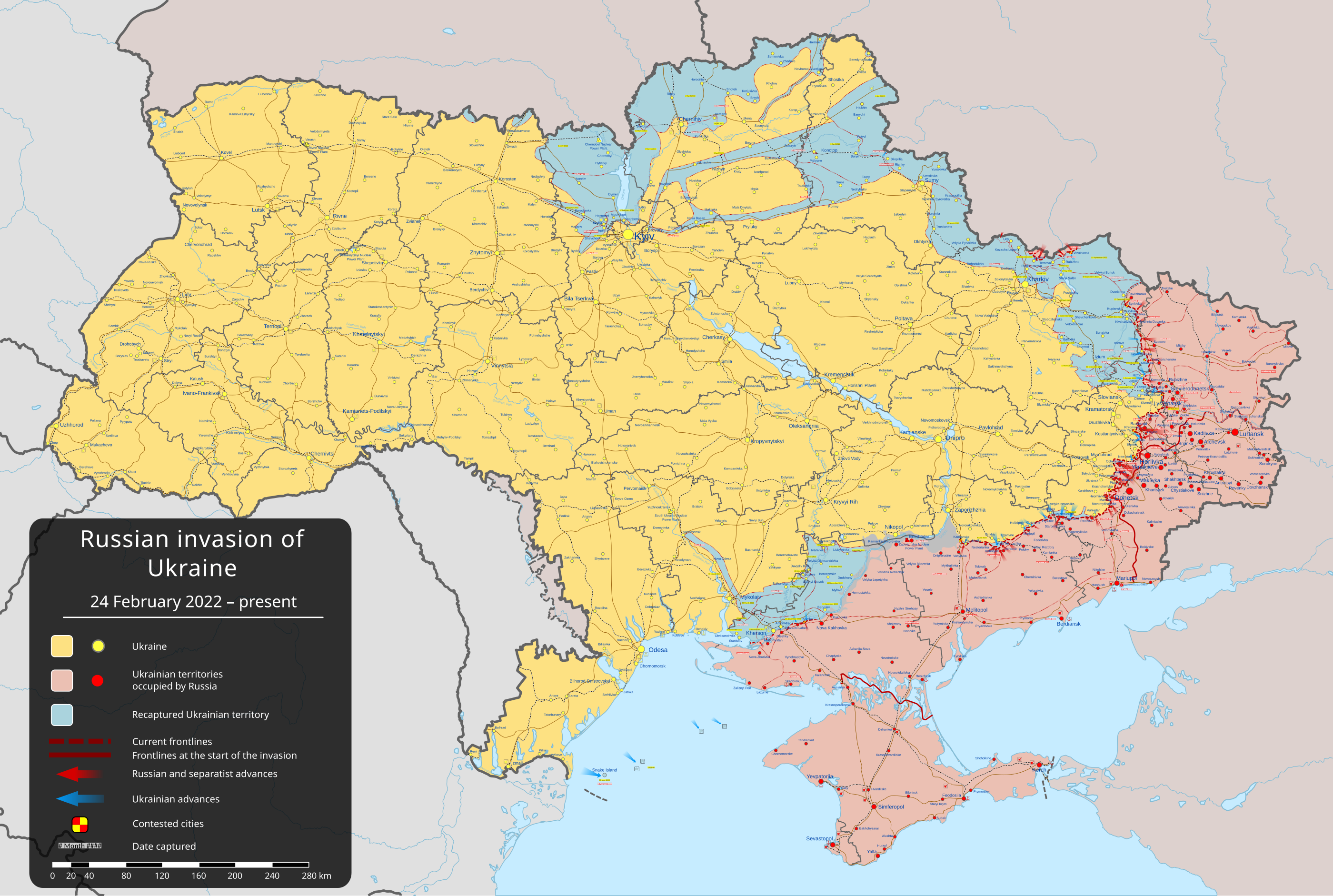

Map of the counteroffensive | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Ukrainian partisans[17] |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The 2022 Ukrainian Kharkiv counteroffensive was an offensive by the Armed Forces of Ukraine on Russian-occupied territory of the Kharkiv Oblast, which was launched on 6 September 2022.[19] Following the launch of the Ukrainian southern counteroffensive in Kherson in late August, Ukrainian forces began a simultaneous counteroffensive in early September in Kharkiv Oblast, in the northeast of the country. Following an unexpected thrust deep into Russian lines, Ukraine recovered many hundreds of square kilometers of territory by 9 September.[20] By 10 September, the Institute for the Study of War said that Ukrainian forces had captured approximately 2,500 square kilometres (970 sq mi) in the Kharkiv region by effectively exploiting the breakthrough,[21] and Reuters reported that Russian forces had been forced to withdraw from their base at Izium after being cut off by the capture of the key railway hub Kupiansk.[22] Despite this major success, Ukrainian forces did not cross the Oskil River and take the east bank of Kupiansk. On September 13, Ukrainian forces established a bridgehead over the Oskil River near Borova.[23]

Background

Russian offensives in the first months of the Russian invasion of Ukraine left large swathes of the Kharkiv Oblast under Russian control, including the key logistical hubs of Izium and Kupiansk.[24][25] The majority of Kharkiv Oblast remained within Ukrainian control, however, including the city of Kharkiv, which was subjected to continuous Russian rocket, artillery, and cluster munition bombardment that persisted into August.[26] Ukrainian forces held off Russian advances towards Kharkiv,[27] then launched counteroffensives in March and May pushing the Russians from the outskirts of the city.[28][29] By June 6, the indiscriminate Russian bombardment of Kharkiv resulted in 606 civilian deaths and 1,248 civilian injuries according to Amnesty International.[30]

The battle lines in the greater Kharkiv Oblast region remained largely static over the next few months as Ukrainian and Western military analysts believed Russia lacked the ground forces to launch a renewed offensive. The Kharkiv death toll exceeded 1,000 by August.[31]

Counteroffensive

Prelude

On 29 August, Ukraine announced an imminent counteroffensive in southern Ukraine, part of a disinformation campaign designed to divert Russia's forces away from Kharkiv.[32][33] Russia redeployed thousands of its troops, including elite units such as the 1st Guards Tank Army, to Kherson Oblast, leaving its Kharkiv forces significantly weakened and vulnerable to attack.[34][35][36]

Initial advance

On 6 September 2022, Ukrainian forces launched a counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region,[37] taking Russian forces by surprise.[38][39][40] In a 10 September interview with the Guardian, Ukrainian special forces spokesman Taras Berezovets stated Russia "thought [the counteroffensive] would be in the south… then, instead of the south, the offensive happened where they least expected, and this caused them to panic and flee.”[33]

Ukrainian troops advanced at least 20 kilometres (12 mi) into Russian-held territory and recaptured some 400 square kilometres (150 sq mi) of territory during the first two days.[41]

By 9 September, Ukraine had broken through Russian lines, with the Ukrainian military saying that it had advanced nearly 50 kilometres (31 mi) and recaptured over 1,000 square kilometres (390 sq mi) of territory.[42] This advance placed them approximately 44 kilometres (27 mi) northwest of Izium,[43] the main Russian logistics base in the region,[38] a rate of advancement largely unseen since Russia withdrew from Kyiv at the start of the war.[34] The fall of Izium on 10 September was described by the Washington Post as a "stunning rout";[44] the Institute for the Study of War assessed that Ukrainian forces had captured approximately 2,500 square kilometres (970 sq mi) in the breakthrough.[21]

One military expert said that it was the first time since World War II that whole Russian units had been lost in a single battle,[25] leading to widespread comparisons to another historical battle fought at Izium: the 1942 Soviet defeat in the Second Battle of Kharkov resulted in over 200,000 Soviet deaths.[45]

Breakthrough and exploitation

On 6 September, having concentrated their forces north of Balakliia, Ukrainian troops launched a counteroffensive in the Kharkiv Oblast, which drove Russian forces back to the left bank of the Donets and Serednya Balakliika rivers. On the same day, Ukrainian forces captured Verbivka, less than 3 km northwest of Balakliia. Several Russian sources reported that Russian forces demolished unspecified bridges on the eastern outskirts of Balakliia to prevent further Ukrainian advances.[35] Ukrainian troops then went on the offensive in the directions of Balakliia, Volokhiv Yar, Shevchenkove, Kupiansk and the districts Savyntsi and Kunye, situated east of Balakliia. According to Russian sources on this line of contact Ukrainians were opposed in some areas of the line by lightly armed forces of the DPR Militia,[19] while Ukrainian sources said that the forces in this region were professional Russian soldiers, not conscripts from the Donbas.[33]

By the following day, Ukrainian forces had advanced some 20 kilometres (12 mi) into Russian-occupied territory, recapturing approximately 400 square kilometres (150 sq mi), and reaching positions northeast of Izium. Russian sources claimed this success was likely due to the relocation of Russian forces to Kherson, in response to the Ukrainian offensive there.[46]

By 8 September, Ukrainian troops had advanced 50 kilometres (31 mi) deep into Russian defensive positions north of Izium. SOBR units of Russian National Guard forces lost control of Balakliia, about 44 km northwest of Izium,[43] although Ukraine did not establish control of the city until 10 September.[47] Near the city, Ukrainian forces recaptured the largest ammunition storage base of the Central Rocket and Artillery Directorate of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.[19] Ukrainian forces also regained control over more than 20 settlements.[48] On the same day, Ukrainian media reported that a high-ranking Russian officer had been captured by Ukrainian forces on the Kharkiv front. Based on footage of the man, it was speculated that he was Lieutenant General Andrei Sychevoi, Commander of the Western Military District of the Russian Armed Forces.[12][13]

On 9 September, the Russian-backed administration ordered the evacuation into Russia of the population from Izium, Kupiansk and Velykyi Burluk.[49] Local residents later reported that at this point Russian soldiers in the area began to flee villages, leaving behind their weaponry, before Ukrainian troops even arrived.[50] Later in the day Ukrainian forces reached Kupiansk, a vital transit hub at the junction of several of the main railway lines supplying Russian troops at the front.[51] The Institute for the Study of War said it believed Kupyansk would likely fall in the next 72 hours.[52] In response to the Ukrainian advance, Russian reserve units were sent as reinforcements to both Kupiansk and Izium.[53]

On 10 September, Kupiansk and Izium were retaken by Ukrainian forces and Ukrainian forces were reportedly advancing towards Lyman.[54][55] An advisor to the head of Kharkiv regional council, Natalia Popova, posted photos on Facebook of soldiers holding a Ukrainian flag outside Kupiansk city hall.[56] Ukrainian security officials and police moved into the recaptured settlements to check the identities of those who stayed under Russian occupation.[57] Later that day, Luhansk Oblast Governor Serhiy Haidai claimed that Ukrainian soldiers had advanced into the outskirts of Lysychansk, while Ukrainian partisans had reportedly managed to capture parts of Kreminna. Haidai stated Russian forces had fled the city, leaving Kreminna "practically empty".[17][58] The New York Times said "the fall of the strategically important city of Izium, in Ukraine's east, is the most devastating blow to Russia since its humiliating retreat from Kyiv.”[59] The Russian Ministry of Defence spokesperson Igor Konashenkov responded to these developments by claiming that Russian forces in the Balakliia and Izium area would "regroup" in the Donetsk area "in order to achieve the stated goals of the special military operation to liberate Donbas". Ukrainian President Zelenskyy said that "The Russian army in these days is demonstrating the best that it can do — showing its back. And, of course, it's a good decision for them to run."[39] He claimed that Ukraine has recaptured 2,000 square kilometres (770 sq mi) since the start of the counteroffensive.[60]

On 11 September, Newsweek reported that Ukrainian forces had "penetrated Russian lines to a depth of up to 70 kilometers in some places and retaken more than 3,000 square kilometers of territory since September 6".[61] Reports that Russian troops had withdrawn from Kozacha Lopan and locals had raised the Ukrainian flag next to the town hall came in from objectiv.tv.[62] A map used in the briefing of the Russian Ministry of Defense on the same day confirmed that Russian forces had withdrawn from Kozacha Lopan, as well as Vovchansk[4] and other settlements on the Ukraine-Russia border.[63] Velykyi Burluk was also retaken.[61]

The entirety of occupied Kharkiv Oblast west of the Oskil River was retaken by Ukraine by 13 September, with state media saying its troops had entered Vovchansk.[64]

Russian withdrawal from Kharkiv Oblast

In the afternoon of 11 September, the Russian Ministry of Defense announced the formal pullout of Russian forces from nearly all of Kharkiv Oblast. The ministry "announced that an 'operation to curtail and transfer troops' was underway."[65][66] At 20:06 that day, Ukrainian critical infrastructure sites (including Kharkiv TEC-5) were hit by Kalibr cruise missiles. The attack left Poltava, Sumy, Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Odesa (partially) and Donetsk Oblasts without electricity.[67][68] Meanwhile, clashes between Ukrainian attackers and Russian defenders continued at Lyman. Ukrainian forces were also reported to possibly have taken Bilohorivka.[11][needs update]

On 12 September, according to the summary of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Defense Forces ousted Russian troops from more than 20 settlements: in particular, the Russians left the villages of Velykyi Burluk and Dvorichna in Kharkiv Oblast.[69] The Russian head of the Kharkiv occupation authority, Vitaly Ganchev, told Russian TV (Rossiya-24) that Ukrainian forces outnumbered Russian forces by "8 times". The border crossing to Russia at Belgorod[clarification needed] has been closed after some 5,000 civilians were "evacuated" to Russia[70]

Other gains

In the morning of 11 September, Ukrainian Governor of Luhansk Oblast, Serhiy Haidai, claimed that Russian forces had mostly left Starobilsk. In the same message, he stated Russian occupational authorities were also leaving cities annexed by Russia in 2014.[71][72][73]

Reports of the Russian military moving out of areas they formerly controlled in Luhansk Oblast began on 12 September alongside a withdrawal from the city of Svatove.[69]

On 12 September, President Zelenskyy said that Ukrainian forces have retaken a total of 6,000 km2 from Russia, in both the south and the east.[74]

According to Oryx, a Dutch-based open source intelligence website, Russia has lost at least 338 pieces of military hardware, from fighter jets to tanks to trucks, that have been destroyed, damaged or captured.[75]

President Zelenskyy claimed on 13 September, during his nightly address, to have recaptured 8000 km2 of territory from Russia. This cannot be independently confirmed.[76]

Reactions

Inside Russia

The near-complete silence of the Russian authorities on the defeat –or any explanation for the developments there– generated considerable anger among some pro-war commentators and Russian nationalists on social media. Some called on 11 September for President Vladimir Putin to make immediate changes to ensure final victory in the war.[77] Some pro-war bloggers called for mobilization inside Russia.[78]

While Ukraine was conducting a counteroffensive, instead of commenting, Vladimir Putin opened a Ferris wheel in Moscow's VDNKh and celebrated Moscow City Day.[79] War bloggers criticized him for continuing the celebrations.[80]

On the evening of 10 September, a festive fireworks display took place in Moscow, which was previously called for to be canceled by many pro-war politicians inside Russia, like Sergey Mironov, the leader of A Just Russia — For Truth.[81][82]

Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov questioned Russian leadership of the war, writing on Telegram:[83] "They have made mistakes and I think they will draw the necessary conclusions. If they don't make changes in the strategy of conducting the special military operation in the next day or two, I will be forced to contact the leadership of the Defense Ministry and the leadership of the country to explain the real situation on the ground."[84]

On September 12, Meduza reported that, per two sources close to the Kremlin, the proposed referendums for the annexation of the self-proclaimed Luhansk and Donetsk People's Republics had been postponed indefinitely, following earlier postponement from September 11 to November 4.[85]

On September 12, Mikhail Sheremet, a State Duma deputy from United Russia, advocated "full mobilization".[86] On September 13, the leader of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation Gennady Zyuganov spoke for the maximum mobilization of forces and resources,[87] but later the Press Secretary of the CPRF Alexander Yushchenko said that Zyuganov called for the mobilization of the economy and resources, and not the population, and recommended to "execute some groups that engage in outright provocations".[88]

Subsequent Russian attacks on Ukrainian infrastructure[89] were interpreted as an attempt to at least partially satisfy demands of radical war supporters in Russia who called for further escalation of Russian tactics.[90][91]

Worldwide

The American Institute for the Study of War (ISW) noted that the rapid pace of the Ukrainian counteroffensive was disrupting the long-held Russian army lines of land communication used to support the Russian army in the northern part of the Luhansk region. According to ISW, this would lead to a serious hindrance to Russia's operations.[92] As of September 11, ISW noted that Western weapons were necessary for the success of Ukraine, but not enough, and skillful planning and execution of the campaign played a decisive role in the lightning success. ISW contended that long preparations and the announcement of a counter-offensive in the Kherson region had confused the Russians, leading to a diversion of the Russian army's attention away from the Kharkiv region, where the Ukrainian army subsequently struck.[11]

On September 10, representatives of the British Ministry of Defence suggested that the Russian army practically had not defended most of the territories recaptured by Ukraine.[93]

Reuters and the BBC called the loss of Izium, which the Russian army had been trying to occupy for over a month at the start of the invasion, a "great humiliation" for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Moscow's worst defeat since the retreat from Kyiv in March.[93][94] According to ISW, the liberation of Izium, occupied in early April, destroyed Russia's prospect of seizing the Donetsk Oblast.[11]

According to Ukrainian foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba, Ukraine's recent counteroffensives prove that the Ukrainian military can end the war faster with more Western weapons, a statement echoed by President Zelenskyy on 12 September.[95] Ukraine's recent successes in Kharkiv Oblast are a crucial confidence boost for a Kyiv that increasingly relies on its Western allies for military aid.[93]

Aftermath

As Ukrainian forces entered towns of Balakliia and Izium, they found numerous places where Ukrainians were held prisoner, tortured and executed by Russian occupation forces.[96] Death toll among civilians as result of the initial Russian siege and subsequent occupation was initially estimated at 1000 residents. After liberation witnesses described residents being detained, abducted, tortured and executed by Russian forces and a number of burial sites were found.[97]

See also

- 2022 Ukrainian southern counteroffensive

- Russian occupation of Kharkiv Oblast

- Battle of Kharkiv (2022)

References

- ^ Zagorodnyuk, Andriy (13 September 2022). "Ukrainian victory shatters Russia's reputation as a military superpower". Atlantic council. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Sengupta, Kim (11 September 2022). "Ukraine claims one of the most significant victories of the war as Russia retreats from key city". The Independent. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (9 September 2022). "Ukraine takes 'substantial' victory over Russians in Kharkiv offensive". The Telegraph. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Russian Troops Retreating From Vovchansk, Population Evacuated". Ukranews. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Tyshchenko, Kateryna (8 September 2022). "Volodymyr Zelenskyy has confirmed the dismissal of the city of Balakliia". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Rebane, Teele; Ochman, Oleksandra (9 September 2022). "Ukrainian forces raise country's flag in Shevchenkove, inch closer to Kupyansk". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Terajima, Asami (8 September 2022). "Ukraine liberates 1,000 square kilometers, over 20 settlements in the Kharkiv Oblast". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "Institute for the Study of War". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ Ministry of Defence of Ukraine [@DefenceU] (10 September 2022). "[...] The Commander of Ukrainian Land Forces, Hero of Ukraine, Colonel General Oleksandr Syrskyi is leading the Ukrainian offensive in this sector. [...]" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Командувача військ західного округу РФ Берднікова зняли з посади після успішного наступу ЗСУ на Харківщині". Цензор.НЕТ (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ a b c d "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 11". Institute for the Study of War. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ a b c "Top Russian Commander of Invading Army Captured by Ukraine—Report". Newsweek. 9 September 2022. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Was der Truppenrückzug Putins aus Charkiw für den Krieg bedeutet". Focus (in German). 11 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f David Axe (8 September 2022). "Ukrainian Brigades Have Punched Through Russian Lines Around Kharkiv". Forbes. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Paratroopers share video of their units' offensive in Kharkiv region". Ukrinform. 10 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Russia hits power stations after Ukraine counter-offensive". Le Monde. 12 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Governor: Ukrainian forces advance to outskirts of Lysychansk, Luhansk Oblast". Kyiv Independent. 10 September 2022. Archived from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "British Defence Intelligence Update Ukraine - 13 September 2022 - Kyiv Post - Ukraine's Global Voice". 13 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Сергей Добрынин (8 September 2022). "Украина диктует ход войны. Наступление ВСУ под Харьковом и Херсоном". Радио Свобода. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Njoka, Eric (9 August 2022). "Moscow sends reinforcement to Kharkiv as Ukraine claims taking several towns and villages from Russia. Is the Russian front crumbling near Kharkiv?". WIO News. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 9". Archived from the original on 2022-09-10. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- ^ Hunder, Max; Hnidyi, Vitalii (10 September 2022). "Russian grip on northeast Ukraine collapses after Kyiv severs supply line". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 13". Institute for the Study of War. September 13, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Korshak, Stefan (5 May 2022). "Ukraine claims RF forces pushed back, no longer can bombard Kharkiv with artillery - Kyiv Post - Ukraine's Global Voice". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Ukraine counter-offensive: Russian forces retreat as Ukraine takes key towns". BBC News. 10 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Reuters (2022-08-19). "UK: Russia bombarding Kharkiv to keep Ukraine from using forces elsewhere". Reuters. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ McCann, Allison; Gamio, Lazaro; Lu, Denise; Robles, Pablo (17 March 2022). "Russia Is Destroying Kharkiv". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Peck, Michael. "Ukraine's Counteroffensive Has Broken Russia's Siege Of Kharkiv". Forbes. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "'The enemy is planning something': Kharkiv fears new Russian attack". the Guardian. 28 June 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine: Hundreds killed in relentless Russian shelling of Kharkiv – new investigation". Amnesty International. 2022-06-12. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ Santora, Marc (17 August 2022). "Missile Strike Kills 6 Civilians in Kharkiv, as Front Remains Static". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Realfonzo, Ugo (September 11, 2022). "Ukraine using disinformation tactics to recapture territory in Kharkiv region". Brussels Times. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ a b c Koshiw, Isobel; Tondo, Lorenzo; Mazhulin, Artem (10 September 2022). "Ukraine's southern offensive 'was designed to trick Russia'". the Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b Hunder, Max; Balmforth, Tom (9 September 2022). "Ukraine retakes territory in Kharkiv region as Russian front crumbles". Reuters. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 6". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 2022-09-08. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ Axe, David. "Russian Troops Are Dashing Around Ukraine Trying To Block Ukrainian Counterattacks". Forbes. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ McCausland, Phil; De Luce, Dan. "Ukraine punches through Russian lines as surprise offensive retakes land in the east". CNBC. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b Townsend, Mark; Tondo, Lorenzo; Koshiw, Isobel (10 September 2022). "Ukrainian counter-offensive in north-east inflicts a defeat on Moscow". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Ukraine's Zelenskyy says Russia's pullback from Kharkiv region 'a good decision'". CBC. Associated Press. 10 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Dlugy, Yana (9 September 2022). "Ukraine Claims Major Gains in Kharkiv". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 7". Archived from the original on 2022-09-09. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ "Zelenskyy announces breakthrough in Ukraine's east and south". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 8". Archived from the original on 2022-09-09. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ "Russia confirms big retreat near Kharkiv as Ukraine offensive advances". Washington Post. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Kuznetsov, Sergei (9 September 2022). "Liberated Ukrainians embrace troops on lightning advance near Kharkiv". Politico. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Karolina Hird, Grace Mappes, George Barros, Layne Philipson, and Mason Clark (7 September 2022). "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 7". understandingwar.org. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hunder, Max; Hnydii, Vitalii (10 September 2022). "Russia loses control of key northeast towns as Ukrainian troops advance". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Жители Балаклеи сообщили, что ВСУ вошли в город". Радио Свобода. 8 September 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-09-08. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ "Окупанти оголосили «евакуацію» з Ізюма, Куп'янська і Великого Бурлука на Харківщині". Слово і Діло (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 2022-09-10. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ Steve Hendrix; Serhii Korolchuk; Robyn Dixon (11 September 2022). "Amid Ukraine's startling gains, liberated villages describe Russian troops dropping rifles and fleeing". Washington Post. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Hunder, Max; Balmforth, Tom (9 September 2022). "'Substantial victory' for Kyiv as Russian front crumbles near Kharkiv". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Reuters; Editing by Cynthia Osterman (9 September 2022). "Ukraine retakes settlements in Kharkiv advance - Russian-installed official". reuters.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tim Lister, Julia Kesaieva and Josh Pennington (9 September 2022). "Russia sends reinforcements to Kharkiv as Ukrainians advance". cnn.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Украинские войска вошли в ранее оккупированный Купянск в Харьковской области. Также сообщается, что ВСУ взяли Изюм и наступают на Лиман". Meduza. Archived from the original on 2022-09-10. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- ^ Anton Troianovski (10 September 2022). "As Russians Retreat, Putin Is Criticized by Hawks Who Trumpeted His War". New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine retakes railway hub as Kharkiv counteroffensive gains ground". Yahoo Finance. 10 September 2022. Archived from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Max Hunder and Vitalii Hnidyi (10 September 2022). "Ukraine troops reach railway hub as breakthrough threatens to turn into rout". reuters.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Governor: Ukrainian partisans raise flag over Kreminna, Luhansk Oblast". The Kyiv Independent. 2022-09-11. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ Gibbons-Neff, Thomas; Santora, Marc (10 September 2022). "Ukrainian Offensive Seen as Reshaping the War's Contours". New York Times. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Hugo Bachega and Matt Murphy (11 September 2022). "Ukraine counter-offensive: Russian forces retreat as Ukraine takes key towns". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Ukraine map reveals how invasion is being rolled back 200 days in". Newsweek. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Над Казачьей Лопанью подняли флаг Украины (фото)". www.objectiv.tv (in Russian). 2022-09-11. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ Анисимова, Ольга (2022-09-11). "ВО: российские войска оставили север Харьковской области, сосредоточив оборону по реке Оскол". RB Новости (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ Harding, Luke; Sabbagh, Dan (14 September 2022). "Ukraine takes control of entire Kharkiv region and towns seized at onset of Russian invasion". the Guardian. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "Russian defense ministry shows retreat from most of Kharkiv region". Meduza. 11 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Russian Defence Ministry Showed Map Of New Frontline In Kharkiv Region, Хартии'97, 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Окупанти вдарили по об'єктах критичної інфраструктури на Харківщині". Главком | Glavcom (in Ukrainian). 2022-09-11. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ Lorenzo Tondo; Isobel Koshiw; Dan Sabbagh; Shaun Walker (11 September 2022). "Russia targets infrastructure in retaliation to rapid Ukraine gains". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ a b "ВСУ объявили об освобождении более 20 населенных пунктов за сутки". Meduza (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ "Ukraine troops 'outnumbered Russia's 8 times' in counterattack". aljazeera. 2022-09-12. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ "Governor: Ukrainian partisans raise flag over Kreminna, Luhansk Oblast". The Kyiv Independent. 2022-09-11. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "Russian invaders leave Kreminna in Luhansk region – regional governor". www.ukrinform.net. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "Война в Украине: Зеленский заявляет о стабилизации обстановки на отвоеванной территории - Новости на русском языке".

- ^ "Ukraine war: We retook 6,000 sq km from Russia in September, says Zelensky". BBC. 2022-09-12. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ Brad Lendon (2022-09-12). "The rot runs deep in the Russian war machine. Ukraine is exposing it for all to see". CNN. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ "Ukraine reclaims more territory from Russia in counteroffensive". AL JAZEERA. AL JAZEERA AND NEWS AGENCIES. 2022-09-13. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ Polityuk, Pavel; Balmforth, Tom (11 September 2022). "Ukraine offensive 'snowballs' with fall of Russian stronghold". Reuters. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "'We have already lost': far-right Russian bloggers slam military failures". The Guardian. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Российские войска уходят с оккупированных территорий в Украине. Что в это время делает Путин". Meduza (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ Semenov, Kolzak (2022-09-11). "Сторонник Путина Кадыров критикует действия российских военных по выводу войск из Украины | Рамзан Кадыров". Orsk.today (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ "Миронов предложил отменить салют в честь Дня Москвы". NEWS.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ "Вой на болотах. Отрицательное наступление второй армии мира". www.unian.net (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ Hugo Bachega and Orla Guerin in Ukraine and Matt Murphy in London (11 September 2022). "Kharkiv offensive: Ukrainian army says it has tripled retaken area". BBC.com. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Ritter, Karl; Arhirova, Hanna (11 September 2022). "Russian troops retreat after Ukraine counteroffensive". ABC news. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Кремль «поставил на стоп» референдумы о «присоединении» оккупированных территорий к России, утверждают источники «Медузы» Их «отложили на неопределенный срок» из-за успешного украинского контрнаступления". Meduza (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ "Депутат Госдумы Шеремет выступил за «полную мобилизацию» в России". РБК (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ "Зюганов призвал к максимальной мобилизации сил и ресурсов". NEWS.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ "В КПРФ назвали провокацией новости о Зюганове, призывающем к мобилизации". NEWS.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Kharkiv blackouts caused by targeted Russian attacks - Zelensky". BBC News. 2022-09-12. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ Pertsev, Andrei (2022-09-14). "Kremlin Must Placate Its Supporters Amid Outrage Over Kharkiv Retreat". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ Kottasová, Ivana (2022-09-13). "Putin's Kharkiv disaster is his biggest challenge yet. It has left him with few options". CNN. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 10". Institute for the Study of War. 10 September 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ a b c "Українська армія потроїла площу звільнених територій". BBC News Україна (in Ukrainian). 2022-09-11. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ Hunder, Max; Hnidyi, Vitalii (2022-09-10). "Russia gives up key northeast towns as Ukrainian forces advance". Reuters. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ "Ukraine pushes to recapture more territory in rapid advance, calls for Western arms". ABC News. 2022-09-13. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Accounts of Russian torture emerge in liberated areas". BBC News. 2022-09-13. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ "'People disappeared': Izium's residents on Russia's occupation". the Guardian. 2022-09-14. Retrieved 2022-09-15.