Prisoner of war: Difference between revisions

Stor stark7 (talk | contribs) →Treatment of POWs by the Allies: Ambrose interviews |

|||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

The [[North Korea]]ns severely mistreated prisoners of war (see [[Korean War#Crimes against POWs|Crimes against POWs]] |

The [[North Korea]]ns severely mistreated prisoners of war (see [[Korean War#Crimes against POWs|Crimes against POWs]] |

||

The Vietnamese captured many U.S. soldiers as prisoners of war. The most notable one was John McCain, who endured more than 5 years of torture. He was offered early release but declined knowing others had served longer than him in the prison. |

The [[Vietnamese]] captured many U.S. soldiers as prisoners of war. The most notable one was [[John McCain]], current [[United States Senator]] and Republican nominee for [[President of the United States]], who endured more than 5 years of torture. He was offered early release but declined knowing others had served longer than him in the prison. |

||

Regardless of regulations determining treatment to prisoners, violation of their rights continue to be reported. Many cases of POW massacres have been reported in recent times, including [[October 13 massacre]] in [[Lebanon]] by Syrian forces and [[Massacre of police officers in Eastern Sri Lanka in June 1990|June 1990 massacre]] in [[Sri Lanka]]. |

Regardless of regulations determining treatment to prisoners, violation of their rights continue to be reported. Many cases of POW massacres have been reported in recent times, including [[October 13 massacre]] in [[Lebanon]] by Syrian forces and [[Massacre of police officers in Eastern Sri Lanka in June 1990|June 1990 massacre]] in [[Sri Lanka]]. |

||

Revision as of 16:15, 13 September 2008

A prisoner of war (POW, PoW, PW, P/W, WP, or PsW) is a combatant who is imprisoned by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict.

Ancient times

For most of human history, depending on the culture of the victors, combatants on the losing side in a battle could expect to be either slaughtered, to eliminate them as a future threat, or enslaved, bringing economic and social benefits to the victorious side and its soldiers. Typically, little distinction was made between combatants and civilians, although women and children were certainly more likely to be spared. Sometimes the purpose of a battle, if not a war, was to capture women, a practice known as raptio; the Rape of the Sabines was a notable mass capture by the founders of Rome. Typically women had no rights, were held legally as chattel, and would not be accepted back by their birth families once they had bore children to those who had killed their brothers and fathers.

Likewise the distinction between POW and slave is not always clear. Some of the indigenous people of the Americas captured Europeans and used their labour and used them as bartering chips; see for example John R. Jewitt, an Englishman who wrote a memoir about his years as a captive of the Nootka people on the Pacific Northwest Coast in 1802-1805.

Qualifications

To be entitled to prisoner-of-war status, captured service members must be lawful combatants entitled to combatant's privilege—which gives them immunity from punishment for crimes constituting lawful acts of war, e.g., killing enemy troops. To qualify under the Fourth Geneva Convention, a combatant must have conducted military operations according to the laws and customs of war, be part of a chain of command, wear a "fixed distinctive marking, visible from a distance" and bear arms openly. Thus, uniforms and/or badges are important in determining prisoner-of-war status; and francs-tireurs, "terrorists", saboteurs, mercenaries and spies may not qualify. In practice, these criteria are not always interpreted strictly. Guerrillas, for example, do not necessarily wear an issued uniform nor carry arms openly, yet captured combatants of this type have sometimes been granted POW status. The criteria are generally applicable to international armed conflicts. In civil wars, insurgents are often treated as traitors or criminals by government forces, and are sometimes executed. However, in the American Civil War, both sides treated captured troops as POWs, presumably out of reciprocity, though the Union regarded Confederacy personnel as separatist rebels. After the hunger-strike by Bobby Sands and his IRA colleagues, the British government allegedly gave some POW privileges to IRA prisoners.[citation needed] However, guerrillas and other irregular combatants generally cannot expect to simultaneously benefit from both civilian and military status.

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, a number of religious wars were particularly ferocious. In Christian Europe, the extermination of the heretics or "non-believers" was considered desirable. Examples include the 13th century Albigensian Crusade and the Northern Crusades.[1] Likewise the inhabitants of conquered cities were frequently massacred during the Crusades against the Muslims in the 11th century and the 12th century. Noblemen could hope to be ransomed; their families would have to send to their captors large sums of wealth commensurate with the social status of the captive. In pre-Islamic Arabia, upon capture, those captives not executed, were made to beg for their subsistence. During the early reforms under Islam, Muhammad changed this custom and made it the responsibility of the Islamic government to provide food and clothing, on a reasonable basis, to captives, regardless of their religion. If the prisoners were in the custody of a person, then the responsibility was on the individual.[2] He established the rule that prisoners of war must be guarded and not ill-treated, and that after the fighting was over, the prisoners were expected to be either released or ransomed. The freeing of prisoners in particular was highly recommended as a charitable act. Mecca was the first city to have the benevolent code applied (rather than what Mecca's people expected: complete massacre). However, Christians who were captured in the Crusades were sold into slavery if they could not pay a ransom.[3]

The 1648 Peace of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years' War, established the rule that prisoners of war should be released without ransom at the end of hostilities and that they should be allowed to return to their homelands.[4]

Modern times

During the 19th century, efforts increased to improve the treatment and processing of prisoners. The extensive period of conflict during the Revolutionary War and Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), followed by the Anglo-American War of 1812, led to the emergence of a cartel system for the exchange of prisoners, even while the belligerents were at war. A cartel was usually arranged by the respective armed service for the exchange of like ranked personnel. The aim was to achieve a reduction in the number of prisoners held, while at the same time alleviating shortages of skilled personnel in the home country.

Later, as result of these emerging conventions a number of international conferences were held, starting with the Brussels Conference of 1874, with nations agreeing that it was necessary to prevent inhumane treatment of prisoners and the use of weapons causing unnecessary harm. Although no agreements were immediately ratified by the participating nations, work was continued that resulted in new conventions being adopted and becoming recognized as international law, that specified that prisoners of war are required to be treated humanely and diplomatically.

Hague and Geneva Conventions

Specifically, Chapter II of the Annex to the 1907 Hague Convention covered the treatment of prisoners of war in detail. These were further expanded in the Third Geneva Convention of 1929, and its revision of 1949. Article 4 of the Third Geneva Convention protects captured military personnel, some guerrilla fighters and certain civilians. It applies from the moment a prisoner is captured until he or she is released or repatriated. One of the main provisions of the convention makes it illegal to torture prisoners and states that a prisoner can only be required to give their name, date of birth, rank and service number (if applicable).

However, nations vary in their dedication to following these laws, and historically the treatment of POWs has varied greatly. During the 20th century, Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany were notorious for atrocities against prisoners during World War II. The German military used the Soviet Union's refusal to sign the Geneva Convention as a reason for not providing the necessities of life to Russian POWs. North Korean and North Vietnamese forces routinely killed or mistreated prisoners taken during those conflicts.

The United States Military Code of Conduct

The United States Military Code of Conduct, Articles III through V, are guidelines for United States service members who have been taken prisoner. They were created in response to the breakdown of leadership which can happen in an atypical environment such as a POW situation, specifically when US forces were POWs during the Korean War. When a person is taken prisoner, the Code of Conduct reminds the service member that the chain of command is still in effect (the highest ranking service member, regardless of armed service branch, is in command), and that the service member cannot receive special favors or parole from their captors, lest this undermine the service member's chain of command.

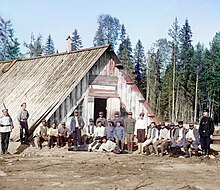

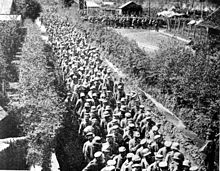

World War I

During World War I about 8 million men surrendered and were held in POW camps until the war ended. All nations pledged to follow the Hague rules on fair treatment of prisoners of war, and in general the POWs had a much higher survival rate than their peers who were not captured.[5] Individual surrenders were uncommon; usually a large unit surrendered all its men. At Tannenberg 92,000 Russians surrendered during the battle. When the besieged garrison of Kaunas surrendered in 1915, 20,000 Russians became prisoners. Over half the Russian losses were prisoners (as a proportion of those captured, wounded or killed); for Austria 32%, for Italy 26%, for France 12%, for Germany 9%; for Britain 7%. Prisoners from the Allied armies totaled about 1.4 million (not including Russia, which lost between 2.5 and 3.5 million men as prisoners.) From the Central Powers about 3.3 million men became prisoners.[6]

Germany held 2.5 million prisoners; Russia held 2.9 million, and Britain and France held about 720,000, mostly gained in the period just before the Armistice in 1918. The US held 48,000. The most dangerous moment was the act of surrender, when helpless soldiers were sometimes shot down. Once prisoners reached a POW camp conditions were better(and often much better than in World War II), thanks in part to the efforts of the International Red Cross and inspections by neutral nations. There was however much harsh treatment of POWs in Germany, as recorded by the American ambassador to Germany (prior to America's entry into the war), James W. Gerard, who published his findings in "My Four Years in Germany". Even worse conditions are reported in the book "Escape of a Princess Pat" by the Canadian George Pearson. It was particularly bad in Russia, where starvation was common for prisoners and civilians alike; about 40% of the prisoners in Russia died or remained missing.[7] Nearly 375,000 of the 500,000 Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war taken by Russians have perished in Siberia from smallpox and typhus.[8] In Germany food was short but only 5% died. [9]

The Ottoman Empire often treated prisoners of war poorly. Some 11,800 British soldiers, most of them Indians, became prisoners after the five-month Siege of Kut, in Mesopotamia, in April 1916. Many were weak and starved when they surrendered and 4,250 died in captivity.[10]

The most curious case came in Russia where the Czech Legion of Czech prisoners (from the Austro-Hungarian army), were released in 1917, armed themselves, and briefly became a military and diplomatic force during the Russian Civil War.

Release of prisoners

At the end of the war in 1918 there were believed to be 140,000 British prisoners of war in Germany, including 3,000 internees held in neutral Switzerland. The first British prisoners were released and reached Calais on 15 November. Plans were made for them to be sent via Dunkirk to Dover and a large reception camp was established at Dover capable of housing 40,000 men, which could later be used for demobilisation.

On 13 December 1918 the armistice was extended and the Allies reported that by 9 December 264,000 prisoners had been repatriated. A very large number of these has been released en masse and sent across Allied lines without any food or shelter. This had created difficulties for the receiving Allies and many released prisoners had died from exhaustion. The released POWs were met by cavalry troops and sent back through the lines in lorries to reception centres where they were refitted with boots and clothing and dispatched to the ports in trains. Upon arrival at the receiving camp the POWs were registered and "boarded" before being dispatched to their own homes. All commissioned officers had to write a report on the circumstances of their capture and to ensure that they had done all they could to avoid capture. Each returning officer and man was given a message from King George V, written in his own hand and reproduced on a lithograph. It read as follows:[citation needed]

The Queen joins me in welcoming you on your release from the miseries & hardships, which you have endured with so much patience and courage.

During these many months of trial, the early rescue of our gallant Officers & Men from the cruelties of their captivity has been uppermost in our thoughts.

We are thankful that this longed for day has arrived, & that back in the old Country you will be able once more to enjoy the happiness of a home & to see good days among those who anxiously look for your return.

George R.I.

World War II

Treatment of POWs by the Axis

Germany and Italy generally treated prisoners from the British Commonwealth, France, the U.S. and other Western allies, in accordance with the Geneva Convention (1929), which had been signed by these countries.[11] Nazi Germany did not extend this level of treatment to non-Western prisoners, such as the Soviets, who suffered harsh conditions and died in large numbers while in captivity. The Empire of Japan also did not treat prisoners of war in accordance with the Geneva Convention. Moreover, according to a directive ratified on 5 August 1937 by Hirohito, the constraints of Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907) were explicitly removed on Chinese prisoners.[12]

In German camps, when soldiers of lower rank were made to work, they were compensated, and officers (e.g. in Colditz Castle) were not required to work. The main complaints of British, British Commonwealth, U.S., and French prisoners of war in German Army POW camps-especially during the last two years of the war-concerned the bare bones menu provided, a fate German soldiers and civilians were also suffering due to the blockade conditions. Fortunately for the prisoners, food packages provided by the International Red Cross supplemented the food rations, until the last few months when allied air raids prevented shipments from arriving. The other main complaint was the harsh treatment during forced marches in the last months, resulting from German attempts to keep prisoners away from the advancing allied forces.

In contrast, Germany treated the Soviet Red Army troops that had been taken prisoner with neglect and deliberate, organized brutality. The first eight months of the German campaign on their Eastern Front were by far the worst phase, with up to 2.4 of 3.1 million POWs dying. Soviet POWs were held under conditions that resulted in deaths of hundreds of thousands from starvation and disease. Most prisoners were also subjected to forced labour under conditions that resulted in further deaths. An official justification used by the Germans for this policy was that the Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention. This was not legally justifiable, however, as under article 82 of the Geneva Convention (1929), signatory countries had to give POWs of all signatory and non-signatory countries the rights assigned by the convention.[13] A month after the German invasion in 1941 an offer was made by the USSR for a reciprocal adherence to the Hague conventions. This 'note' was left unanswered by Third Reich officials [14].

According to some sources, between 1941 and 1945, the Axis powers took about 5.7 million Soviet prisoners. About 1 million of them were released during the war, in that their status changed but they remained under German authority. A little over 500,000 either escaped or were liberated by the Red Army. Some 930,000 more were found alive in camps after the war. The remaining 3.3 million prisoners (57.5% of the total captured) died during their captivity.[15] According to Russian military historian General G. Krivoshhev, 4.6 million Soviet prisoners were taken by the Axis powers, of which 1.8 million were found alive in camps after the war and 318,770 were released by the Axis during the war and were then drafted into the Soviet armed forces again.[16]. In comparison, 8,348 Western Allied (British, American and Canadian) prisoners died in German camps in 1939-45 (3.5% of the 232,000 total).

On 11 February 1945, at the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, the United States and the United Kingdom signed a Repatriation Agreement with the USSR.[17] The interpretation of this Agreement resulted in the forcible repatriation of all Russians (Operation Keelhaul) regardless of their wishes. The forced repatriation operations took place in 1945-1947.[18] Many Soviet POWs and forced laborers transported to Nazi Germany were on their return to the USSR treated as traitors and sent to the gulag. The remainder were barred from all but the most menial jobs.

During Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War, the Empire of Japan which had never signed the Third Geneva Convention of 1929, violated however international agreements, including provisions of the Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907), which protect prisoners of war (POWs).

Prisoners of war from China, the United States, Australia, Britain, Canada, India, the Netherlands, New Zealand and the Philippines held by the Japanese armed forces were subject to murder, beatings, summary punishment, brutal treatment, forced labor, medical experimentation, starvation rations and poor medical treatment. No access to the POWs was provided to the International Red Cross. Escapes were almost impossible because of the difficulty of men of European descent hiding in Asiatic societies.[19]

According to the findings of the Tokyo tribunal, the death rate of Western prisoners was 27.1% (American POWs died at a rate of 37%),[20] seven times that of POWs under the Germans and Italians.[21] The death rate of Chinese was much larger. Thus, while 37,583 prisoners from the UK, 28,500 from Netherlands and 14,473 from USA were released after the surrender of Japan, the number for the Chinese was only 56.[22]

Treatment of POWs by the Allies

As a result of the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, hundreds of thousands of Polish soldiers became prisoners of war in the Soviet Union. Thousands of them were executed; over 20,000 Polish military personnel and civilians perished in the Katyn massacre.[23] Out of Anders' 80,000 evacuees from Soviet Union gathered in Great Britain only 310 volunteered to return to Poland in 1947.[24]

According to some sources, the Soviets captured 3.5 million Axis servicemen (excluding Japanese) of which more than a million died.[25] According to G. Krivoshhev, the Soviets captured in total 4,126,964 Axis servicemen, of which 580,548 died in captivity. Of 2,389,560 German servicemen 450,600 died in captivity.[16] One specific example of the tragic fate of the German POWs was after the Battle of Stalingrad, during which the Soviets captured 91,000 German troops, many already starved and ill, of whom only 5,000 survived the war. The last German POWs (those who were sentenced for war crimes, sometimes without sufficient reasons) were released by the Soviets in 1955, only after Joseph Stalin had died.[26] At least 54,000 Italian POWs died in Russia, with a mortality rate of 84.5%. See also POW labor in the Soviet Union, Japanese prisoners of war in the Soviet Union, Italian prisoners of war in the Soviet Union, Romanian POW in the Soviet Union.

During the war Allied nations such as the U.S.,[citation needed] UK,[citation needed] Australia[citation needed] and Canada[27] tried to treat Axis prisoners strictly in accordance with the Geneva Convention (1929). According to Stephen E. Ambrose, of the roughly 1000 U.S. combat veterans that he had interviewed, roughly 1/3 told him they had seen U.S. troops kill German prisoners.[28]

Japanese prisoners sent to camps in the U.S. fared well but many Japanese were killed when trying to surrender or were massacred just after they had surrendered. (see Allied war crimes during World War II in the Pacific). Some Japanese prisoners in POW camps died at their own hands, either directly or by attacking guards with the intention of forcing the guards to kill them.

Towards the end of the war, as large numbers of Axis soldiers surrendered, the U.S. created the designation of Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF) so as not to treat prisoners as POWs. A lot of these soldiers were kept in open fields in various Rheinwiesenlagers. Controversy has arisen about how Eisenhower managed these prisoners. [4] (see Eisenhower and German POWs). Many died when forced to clear minefields in Norway, France etc. How many died during the several post-war years that they were used for forced labor in France, the Soviet Union, etc, is disputed.

See also List of World War II POW camps and Gulag[29]

Post World War II

The North Koreans severely mistreated prisoners of war (see Crimes against POWs

The Vietnamese captured many U.S. soldiers as prisoners of war. The most notable one was John McCain, current United States Senator and Republican nominee for President of the United States, who endured more than 5 years of torture. He was offered early release but declined knowing others had served longer than him in the prison.

Regardless of regulations determining treatment to prisoners, violation of their rights continue to be reported. Many cases of POW massacres have been reported in recent times, including October 13 massacre in Lebanon by Syrian forces and June 1990 massacre in Sri Lanka.

During the 1990s Yugoslav Wars, Serb forces committed many POW massacres, including: Vukovar, Škarbrnja and Srebrenica massacres.

In 2001, there were reports that India had actually taken two prisoners during the Sino-Indian War, Yang Chen and Shih Liang. The two were imprisoned as spies for three years before being interned in a mental asylum in Ranchi, where they spent the next 38 years under a special prisoner status.[30]

The last prisoners of Iran–Iraq War (1980-1988) were exchanged in 2003.[31]

About six months after the 2003 invasion of Iraq rumors of Iraq prison abuse scandals started to emerge. The best known abuse incidents occurred at the large Abu Ghraib prison.

Numbers of POWs

This is a list of nations with the highest number of POWs since the start of World War II, listed in descending order. These are also the highest numbers in any war since the Geneva Convention, Relative to the treatment of prisoners of war (1929) entered into force 19 June, 1931. The USSR had not signed the Geneva convention.[32]

| Prisoner nationality | Number | Name of conflict |

| 4 - 5.7 million taken by Germany (2.7 - 3.3 million died in German POW camps) [33] (ref. Streit) | World War II (Total) | |

3,127,380 taken by U.S.S.R. (474,967 died in captivity) [33]

|

World War II | |

| 1,800,000 taken by Germany | Battle of France in World War II | |

| 675,000 (420,000 by Germans, 240,000 by Soviets in 1939; 15,000 Warsaw 1944) | World War II | |

| ~200,000 (135,000 taken in Europe, does not include Pacific or Commonwealth figures) | World War II | |

| ~130,000 (95,532 taken by Germany) | World War II | |

| 90,368 taken by India | Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 |

List of notable POWs

List of POWs that attracted notable attention or influence by this status:

- Ali Akbar Abotorabi Fard - Iranian cleric, was a POW in the Iran–Iraq War for more than 10 years

- Ron Arad - Israeli fighter pilot, shot down over Lebanon in 1986. He hasn't been seen or heard from since 1988 and is widely presumed to be dead.

- Douglas Bader - legless British fighter pilot, squadron commander in Battle of Britain

- Leonard Birchall - The "Saviour of Ceylon"

- Fernand Braudel - the famous historian, was a POW in World War II.

- Winston Churchill - during the Second Boer War; escaped

- James Clavell - prisoner in Singapore, based his novel King Rat on his experiences during World War II

- George Thomas Coker - US Navy aviator, POW in North Vietnam, noted resistor of his captors

- John Cordwell - forged documents to help fellow English soldiers get out of Germany as part of the Great Escape

- Charles de Gaulle - French general and political leader, captured at Verdun, POW 1916-18

- Dieter Dengler - a United States Navy pilot who escaped a Pathet Lao prison camp in Laos

- Jeremiah Denton - Awarded the Navy Cross for resistance in captivity during the Vietnam War

- Roy Dotrice - British actor

- Werner Drechsler - killed by fellow German POWs during World War II for informing on other prisoners

- Sir Edward "Weary" Dunlop - an Australian surgeon and legend among prisoners of the Thai Burma Railway in World War II

- Yakov Dzhugashvili - Joseph Stalin's first son, was captured by Germans during World War II and killed in 1943.

- Denholm Elliott - British actor

- Henri Giraud - French general, escaped German captivity in both World War I and World War II

- Ernest Gordon - Author of "To End All Wars" and former Presbyterian Dean of Princeton University chapel

- E.R. (Bon) Hall - Australian Officer, prisoner of the Thai Burma Railway in World War II

- James Hargest - Brigadier in WW2. Highly decorated New Zealand politician in WW1 and WW2. Escaped from captivity into Switzerland.

- Erich Hartmann - "The Blond Knight of Germany". Number one air ace of all air forces in WW2.

- Bob Hoover - American World War II pilot, test pilot and airshow performer; captured in 1944 and escaped from Stalag Luft I

- Wilm Hosenfeld - most remembered for saving Polish pianist and composer Władysław Szpilman from death in the ruins of Warsaw.

- Alija Izetbegovic - President of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was held as hostage for several days by JNA forces during the Bosnian War

- Andrew Jackson - Seventh President of the United States, captured in the American Revolutionary War as a thirteen-year-old courier

- Stanley D. Jaworski - Polish POW freed by American soldiers

- Harold K. Johnson - U.S. Army Chief of Staff 1964; captured at Bataan (1942-45)

- Arthur Koestler - interned in a camp for enemy aliens at the beginning of World War II

- Tikka Khan - Chief of Army Staff of Pakistan Army

- Wajid Khan Canadian politician - former Pakistan-India War 1971 fighter pilot

- Yahya Khan - last president of a united Pakistan

- Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski - Commander of the Polish Home Army, and in the Warsaw Uprising

- Gustav Krist - Adventurer and traveler, Austrian soldier in World War I, captured by Russians in 1914. Interned in Russian Turkestan

- Desmond Llewelyn – went on to a notable acting career, most famously as Q in the James Bond film series

- Jessica Lynch - highly decorated American servicewoman during the Iraq war.

- Manda Manchiani - captured in 1941 during World War II, attempted escape multiple times then finally she was freed in 1945

- Keith Matthew Maupin - captured on April 9, 2004. Date of murder unknown. Remains found March 30, 2008.

- Charles Cardwell McCabe - a prisoner and chaplain at Libby Prison during the American Civil War

- John McCain - American political leader and Republican nominee for president in 2008, prisoner for over five years in Vietnam

- Olivier Messiaen - French composer

- Dusty Miller - Executed for his faith during internment under the Japanese in Thailand in 1945.[citation needed]

- François Mitterrand - French president, captured during World War II in 1940, escaped 6 times before arriving home in Dec. 1941

- W. H. Murray - Scottish mountaineer

- Airey Neave - British politician

- A. A. K. Niazi - commander of Pakistan Army in East Pakistan who surrendered along with nearly 93,000 prisoners

- Manuel Noriega - Ex-Panamanian dictator captured by US troops in 1990 then jailed for drugs trafficking offences. Only detainee in held by US authorities presently officially designated as a POW by the federal government.

- Friedrich Paulus - German field marshal, surrendered Stalingrad to the Soviets in 1943; outspoken critic of Hitler

- Donald Pleasance - English film and stage actor. Was shot down while serving in the RAF during World War II, taken prisoner, and placed in a German prisoner-of-war camp. He would later act in the film "The Great Escape".

- Patrick Reid - non-fiction/historical author

- Yevgeny Rodionov - Russian soldier captured by rebel forces in Chechnya and executed by beheading for refusing to convert to Islam

- Jerry Sage - OSI agent - World War II - Steve McQueen character was loosely based on him in the movie "The Great Escape"

- Jean-Paul Sartre - French philosopher and writer, POW 1940-41

- Kazuo Sakamaki - First POW captured by U.S. forces in World War II

- Ronald Searle - English cartoonist

- Léopold Senghor - Senegalize writer and political leader, captured 1940 in France

- Gilad Shalit - Israeli soldier whose capture in 2006 sparked Israel's war against Hamas. He is still being held.

- William Stacy - lieutenant colonel of the Continental Army, captured during the Cherry Valley massacre; General George Washington attempted to orchestrate a prisoner exchange for Lt. Col. Stacy[35] but was unsuccessful.

- James Stockdale - candidate for Vice President in 1992; decorated member of the U.S. Navy; POW in Vietnam

- E W Swanton - captured by Japanese in Singapore; after war, was renowned BBC sports commentator.

- Floyd James Thompson - America's longest-held POW; he spent 9 years in POW camps in Vietnam (1964 - 1973)

- Josip Broz Tito - president of Yugoslavia, Austrian soldier in World War I, captured by Russians in 1915

- Mikhail Tukhachevsky - Soviet military leader and theorist, captured by Germans in World War I

- Charles Upham - Most decorated British soldier of WW2. Awarded the Victoria Cross twice.

- Laurens van der Post - South African writer and war hero, captured by Japanese 1942

- Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach - German anti-Nazi general captured at Stalingrad by Soviets

- Kurt Vonnegut - American writer; captured in the Battle of the Bulge and witnessed the Bombing of Dresden in World War II

- Jonathan Wainwright - Commanding General US forces in Philippines; captured at Bataan (1942-1945)

- George Washington - first U.S. President, captured in 1754 by the French during the French and Indian War.

- D. C. Wimberly - POW in World War II from Springhill, Louisiana, past commander of American Ex-Prisoners of War

- Louis Zamperini - American athlete, member of Olympic team, captured by Japanese 1943

See also

- KIA– Killed In Action

- MIA– Missing In Action

- WIA– Wounded in action

- American Revolution prisoners of war

- British prison ships (New York)

- Combatant

- Disarmed Enemy Forces

- Geneva Convention

- Illegal combatant

- Laws of war

- Postal censorship

- Prisoner-of-war camp

- Prison escape

- The United States Military Code of Conduct

- War crime

- Civilian Internee

- Camps for Russian prisoners and internees in Poland (1919–1924)

- Soviet POWs in German captivity

- Polish prisoners of war in the Soviet Union (after 1939)

Movies

- 1971

- Andersonville

- Blood Oath

- The Bridge on the River Kwai

- The Brylcreem Boys

- Danger Within

- The Deerhunter

- Empire of the Sun

- Escape to Athena

- Grand Illusion

- The Great Escape

- The Great Raid

- The McKenzie Break

- Hart's War

- Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence

- Missing in Action

- The One That Got Away

- Prisoner of War (there are several films of this title available here)

- Rambo: First Blood Part II

- Rescue Dawn

- Stalag 17

- Summer of My German Soldier

- Tea with Mussolini

- To End All Wars

- Uncommon Valor

- The Wooden Horse

Songs

- Prisoners of War

References

- ^ "History of Europe, p.362 - by Norman Davies ISBN 0-19-520912-5

- ^ Maududi (1967), Introduction of Ad-Dahr, "Period of revelation", p. 159.

- ^ Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam. Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 115.

- ^ "Prisoner of war", Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Geo G. Phillimore and Hugh H. L. Bellot, "Treatment of Prisoners of War", Transactions of the Grotius Society, Vol. 5, (1919), pp. 47-64.

- ^ Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War. (1999) p 368-9 for data.

- ^ Prisoners of War and Communism.

- ^ 375,000 Austrians Have Died in Siberia; Remaining 125,000 War Prisoner... - Article Preview - The New York Times

- ^ Richard B. Speed, III. Prisoners, Diplomats and the Great War: A Study in the Diplomacy of Captivity. (1990); Ferguson, The Pity of War. (1999) ch 13; Desmond Morton, Silent Battle: Canadian Prisoners of War in Germany, 1914-1919. 1992.

- ^ British National Archives, "The Mesopotamia campaign", at [1];

- ^ International Humanitarian Law - State Parties / Signatories

- ^ Akira Fujiwara, Nitchû Sensô ni Okeru Horyo Gyakusatsu, Kikan Sensô Sekinin Kenkyû 9, 1995, p.22

- ^ "Part VIII : Execution of the convention #Section I : General provisions". Retrieved 2007-11-29..

- ^ Beevor, Stalingrad . Penguin 2001 ISBN 0141001313 p60

- ^ Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II

- ^ a b Report at the session of the Russian assosiation of WWII historians in 1998

- ^ Repatriation -- The Dark Side of World War II

- ^ Forced Repatriation to the Soviet Union: The Secret Betrayal

- ^ Prisoners of the Japanese : Pows of World War II in the Pacific - by Gavin Dawes, ISBN 0-688-14370-9

- ^ "Japanese Atrocities in the Philippines".

- ^ Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors, 1996, p.2,3.

- ^ Tanaka, ibid., Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, 2001, p.360

- ^ Fischer, Benjamin B., "[The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field]", Studies in Intelligence, Winter 1999-2000.

- ^ Michael Hope - "Polish deportees in the Soviet Union".

- ^ German POWs and the Art of Survival

- ^ German POWs in Allied Hands - World War II

- ^ Tremblay, Robert, Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, et all. "Histoires oubliées – Interprogrammes : Des prisonniers spéciaux" Interlude. Aired: 20 July 2008, 14h47 to 15h00.

- Rogers Cable Inc. Ottawa, Ontario. Channel 12, TFO,[2][3] Accessed: 20 July 2008, approx. 14h45 to 15h00. [edit] Note: See also Saint Helen's Island.

- ^ James J. Weingartner, "Americans, Germans, and War Crimes: Converging Narratives from "the Good War" the Journal of American History, Vol. 94, No. 4. March 2008

- ^ The Gulag Collection: Paintings of Nikolai Getman

- ^ Shaikh Azizur Rahman, "Two Chinese prisoners from '62 war repatriated", The Washington Times.

- ^ "THREATS AND RESPONSES: BRIEFLY NOTED; IRAN-IRAQ PRISONER DEAL", by Nazila Fathi, New York Times, March 14, 2003

- ^ Clark, Alan Barbarossa: The Russian-German Conflict 1941-1945 page 206, ISBN 0-304-35864-9

- ^ a b "Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century", Greenhill Books, London, 1997, G. F. Krivosheev, editor

- ^ Kriegsgefangene: Viele kamen nicht zurück - Politik - stern.de

- ^ Sparks, Jared: The Writings of George Washington, Vol VII, Harper and Brothers, New York (1847) p. 211.

Other references:

- Full text of Third Geneva Convention, 1949 revision

- "Prisoner of War". (CD Edition ed.). 2002.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|ency=ignored (help) - Gendercide site

- "Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century", Greenhill Books, London, 1997, G. F. Krivosheev, editor.

- "Keine Kameraden. Die Wehrmacht und die sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen 1941-1945", Dietz, Bonn 1997, ISBN 3-8012-5023-7

Further reading

- Roger DEVAUX : Treize Qu'ils Etaient - Life of the french prisoners of war at the peasants of low Bavaria (1939-1945) - Treize Qu'ils Etaient - Mémoires et Cultures - 2007 - ISBN 2-916062-51-3

- Pierre Gascar, Histoire de la captivité des Français en Allemagne (1939-1945), Éditions Gallimard, France, 1967.

- McGowran OBE, Tom, Beyond the Bamboo Screen: Scottish Prisoners of War under the Japanese. 1999. Cualann Press Ltd

- Bob Moore,& Kent Fedorowich eds., Prisoners of War and their Captors in World War II, Berg Press, Oxford, UK, 1997.

- David Rolf, Prisoners of the Reich, Germany's Captives, 1939-1945, 1998.

- Richard D. Wiggers "The United States and the Denial of Prisoner of War (POW) Status at the End of the Second World War", Militargeschichtliche Mitteilungen 52 (1993) pp. 91-94.

- Winton, Andrew, Open Road to Faraway: Escapes from Nazi POW Camps 1941-1945. 2001. Cualann Press Ltd.

- The stories of several American fighter pilots, shot down over North Vietnam are the focus of American Film Foundation's 1999 documentary Return with Honor, presented by Tom Hanks.

- Lewis H. Carlson, WE WERE EACH OTHER'S PRISONERS: An oral history of World War II American and German Prisoners Of War, 1st Edition.; 1997, BasicBooks (HarperCollins, Inc).ISBN 0-465-09120-2.

- Arnold Krammer, NAZI PRISONERS OF WAR IN AMERICA; 1979 Stein & Day; 1991, 1996 Scarborough House. ISBN 0-8128-8561-9.

- Alfred James Passfield, The Escape Artist; An WW2 Australian prisoner's chronicle of life in German POW camps and his eight escape attempts, 1984 Artlook Books Western Australia. ISBN 0 86445 047 8.

External links

- The National Archives ADM 103 Prisoners of War 1755-1831

- The National Archives 'Your Archives'

- The National Archives 'Your Archives' - ADM 103 Prisoners of War 1755-1831

- Archive of WWII memories, gathered by BBC

- POWs of WWII and their experiences

- Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II

- Current staus of Vietnam War POW/MIA

- Australian POW FX Larkin NX43393 AIF. Detailed web site and rich resources.

- CBC Digital Archives - Canada's Forgotten PoW Camps

- German army list of Stalags

- German army list of Oflags

- Changi A.I.F. Ski Club

- Colditz Oflag IVC POW Camp

- Lamsdorf Reunited

- Website (official) on New Zealand PoWs

- New Zealand Official History, New Zealand PoWs of Germany, Italy & Japan

- Essays on New Zealand PoWs of Germany, Italy & Japan

- Essay on Escapes of New Zealand PoWs

- Stoker Harold Siddall Royal Navy, captured on Crete 1941, and his life in Stalag VIIA

- Notes of Japanese soldier in a USSR prison camp after WWII

- Fate of a 1950 Korean War POW-MIA fate at [1] {reference only}

- Location of POW-camps in the Soviet Union