Origin of the Albanians: Difference between revisions

m Undid revision 248189114 by 41.245.185.54 (talk) |

|||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

There are some direct correspondences of vocabulary between Albanian and Illyrian,<ref name="ref7">Jirecek, Konstantin. "The history of the Serbians" (''Geschichte der Serben''), Gotha, 1911</ref> but none of these correspondences is conclusive for the purpose of determining whether or not Albanian is an Illyrian language. A number of Illyrian lexical items ([[toponym]]s, [[hydronym]]s, [[oronym]]s, [[anthroponym]]s, etc.) have been linked to Albanian. |

There are some direct correspondences of vocabulary between Albanian and Illyrian,<ref name="ref7">Jirecek, Konstantin. "The history of the Serbians" (''Geschichte der Serben''), Gotha, 1911</ref> but none of these correspondences is conclusive for the purpose of determining whether or not Albanian is an Illyrian language. A number of Illyrian lexical items ([[toponym]]s, [[hydronym]]s, [[oronym]]s, [[anthroponym]]s, etc.) have been linked to Albanian. |

||

To propagate the connection, the Albanian communist regime adopted a policy of artificially naming people with "Illyrian" names.<ref>Vickers, Miranda. ''The Albanians''. I.B. Tauris, 1999, ISBN 960-210-279-9, p. 196. "From time to time official lists were published with pagan, so-called Illyrian or freshly minted names considered appropriate for the new breed of revolutionary Albanians."</ref> |

To propagate the connection, the Albanian communist regime adopted a policy of artificially naming people with "Illyrian" names.<ref>Vickers, Miranda. ''The Albanians''. I.B. Tauris, 1999, ISBN 960-210-279-9, p. 196. "From time to time official lists were published with pagan, so-called Illyrian or freshly minted names considered appropriate for the new breed of revolutionary Albanians."</ref> This is not to say that other places with (ethnic) Albanian majorities did not name their children with ''Illyrian'' names. ''Ilir'' and 'iliriana', 'teuta' and 'dardan' are notable examples of ''Illyrian names used in places such as Kosovo and parts of Western FYRM |

||

===Disagreement on the Illyrian theory=== |

===Disagreement on the Illyrian theory=== |

||

Revision as of 22:13, 4 November 2008

| History of Albania |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

|

| Culture |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

The origin of the Albanians has been for some time a matter of dispute among historians. Most of them conclude that they are descendants of an ancient Balkan people, but are divided as to which one, with the most popular ones being the Illyrians, Dacians or Thracians. Albanians are people who speak Albanian, an Indo-European language. Though the vocabulary contains some Greek, Latin, Italian, Slavic and Turkish loanwords, the language per se has no other close living relative, constituting its own branch of Indo-European, making it difficult to determine from what language it evolved. However, despite their linguistic uniqueness, studies in genetic anthropology suggest that the Albanians come from the same common source as most other European peoples.[1]

Place of origin

The place where the Albanian language was formed is also uncertain, but analysis has suggested that it was in a mountainous region, rather than in a plain or seacoast: while the words for plants and animals characteristic of mountainous regions are entirely original, the names for fish and for agricultural activities (such as ploughing) are borrowed from other languages.

It can also be presumed that the Albanians did not live in Dalmatia, because the Latin influence over Albanian is of Eastern Romance origin, rather than of Dalmatian origin. This influence includes Latin words exhibiting idiomatic expressions and changes in meaning found only in Eastern Romance and not in other Romance languages. Adding to this the many words found in Romanian with Albanian cognates (see Eastern Romance substratum), it may be assumed that Romanians and Albanians lived in close proximity at one time. Generally, the areas where this might have happened are considered to be regions varying from Transylvania, what is now Eastern Serbia (the region around Naissus), Kosovo and Northern Albania.

However, most agricultural terms in Romanian are of Latin origin, but not the terms related to city activities — indicating that Romanians were an agricultural people in the low plains, as opposed to Albanians, who were originally shepherds in the highlands.

Some scholars even explain the gap between the Bulgarian and Serbian languages by postulating an Albanian-Romanian buffer-zone east of the Morava river. Although an intermediary Serbian dialect exists, it was formed only later, after the Serbian expansion to the east.

Another argument that sustains a northern origin of the Albanians is the relatively small number of words of Greek origin, although Southern Illyria was under the influence of Greek/Byzantine civilization and language, especially after the breakdown of the Roman Empire.

Written sources

See also:Albania (toponym).

The following written sources are presented as relevant to the origin of the Albanians:

References to early peoples of uncertain ethnic identity

- In the 2nd century BC, the History of the World written by Polybius, mentions a city named Arbon in present day central Albania. The people who lived there were called Arbanios and Arbanitai.

- In the 1st century AD, Pliny mentions an Illyrian tribe named Olbonenses.

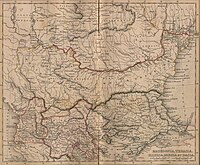

- In the 2nd century AD, Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer from Alexandria, drafted a map of remarkable significance for the history of Illyria. This map shows the city of Albanopolis (located Northeast of Durrës). Ptolemy also mentions the Illyrian tribe named Albanoi, who lived around this city.

Disputed references to Albanians

- In History written in 1079-1080, Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium. It is disputed, however, whether that refers to Albanians in an ethnic sense.[2]

- The earliest Serbian source mentioning "Albania" (Ar'banas') is a charter by Stefan Nemanja, dated 1198, which lists the region of Pilot (Pulatum) among the parts Nemanja conquered from Albania (ѡд Арьбанась Пилоть, "de Albania Pulatum").[3]

- 1285 in Dubrovnik (Ragusa) a document states: "Audivi unam vocem clamantem in monte in lingua albanesca" (I heard a voice crying in the mountains in the Albanian language).[4] It is unclear, however, whether this sentence refers to the Albanian language (or to which one of its two dialects), or whether it denotes another language spoken in the geographical or political region of Albania, such as Slavic, Greek or Italian.

Undisputed references to Albanians

- Arbanitai of Arbanon are recorded in an account by Anna Comnena of the troubles in that region during the reign of her father Alexius I Comnenus (1081-1118) by the Normans.[5]

- The first document in the Albanian language (as spoken in the region around Mat) was recorded in 1462 by Paulus Angelus (whose name was later albanized to Pal Engjëll), the archbishop of the catholic Archdiocese of Durazzo.[6]

First mentions

The word Shqiptar, by which Albanians today refer to themselves since the Ottoman times, was recorded for the first time in the 14th century, and it appears to have been a family name (Schipudar, Scapuder, Schepuder) in the city of Drivast.

Ethnic origin

The three chief candidates considered by historians are Illyrian, Dacian, or Thracian, though there were other non-Greek groups in the ancient Balkans, including Paionians (who lived north of Macedon) and Agrianians. The Illyrian language and the Thracian language are generally considered to have been on different Indo-European branches. Not much is left of the old Illyrian, Dacian or Thracian tongues, making it difficult to match Albanian with them.

There is debate whether the Illyrian language was a Centum or Satem language. Some evidence suggests that it was centum, but it is not conclusive. It is also uncertain whether Illyrians spoke a homogeneous language or rather a collection of different but related languages that were wrongly considered the same language by ancient writers. Many of those tribes, along with their language, are no longer considered Illyrian.[7][8] The same is sometimes said of the Thracian language. For example, based on the toponyms and other lexical items, Thracian and Dacian were probably different but related languages.

In the early half of the 20th century, many scholars thought that Thracian and Illyrian were one language branch, but due to the lack of evidence, most linguists are skeptical and now reject this idea, and usually place them on different branches.

The origins debate is often politically charged, and to be conclusive more evidence is needed. Such evidence unfortunately may not be easily forthcoming because of a lack of sources. Scholars are beginning to move away from a single-origin scenario of Albanian ethnogenesis. The area of what is now Macedonia and Albania was a melting pot of Thracian, Illyrian and Greek cultures in ancient times.[citation needed]

Illyrian origin

The theory that Albanians were related to the Illyrians was proposed for the first time by a German historian in 1774.[9] There are two variants of the theory: one is that the Albanian language represents a survival of an indigenous Illyrian language spoken in what is now Albania. The other is that the Albanian language is the descendant of an Illyrian language that was spoken north of the Jireček Line and probably north or northeast of Albania.

There is a gap of several centuries between the last historical mention of Illyrians (and the Illyrian tribe Albanoi) and the later mention of Albanians and of the names Albanon and Arbanon to indicate the region. Supporters of either theory say that the term Albanian gradually came to be applied to the surviving Illyrians.

There are some direct correspondences of vocabulary between Albanian and Illyrian,[10] but none of these correspondences is conclusive for the purpose of determining whether or not Albanian is an Illyrian language. A number of Illyrian lexical items (toponyms, hydronyms, oronyms, anthroponyms, etc.) have been linked to Albanian.

To propagate the connection, the Albanian communist regime adopted a policy of artificially naming people with "Illyrian" names.[11] This is not to say that other places with (ethnic) Albanian majorities did not name their children with Illyrian names. Ilir and 'iliriana', 'teuta' and 'dardan' are notable examples of Illyrian names used in places such as Kosovo and parts of Western FYRM

Disagreement on the Illyrian theory

Some historians, ethnologists and archaeologists refute the theory of the Illyrian origin of Albanians. In the book "The Illyrians", author John Wilkes writes that Albanians are likely to be of other origin than Illyrian.[12]

Continuity in Albania south of the Jireček Line

Many problems for the theory of Albanian continuity in Albania are recognized, and are addressed in various ways as the case may be.

One problem is the lack of clear archaeological evidence for a continuous settlement of an Albanian-speaking population since Illyrian times. For example, while several scholars maintain that the Komani-Kruja burial sites support the Illyrian-Albanian continuity theory, other scholars reject this and consider that the remains indicate a population of Romanized Illyrians who spoke a Romanic language.[13][10]

The lack or scarcity of definite loans from ancient Greek into Albanian is another problem.[14] As the Jireček Line shows, if Albanians were continuously settled throughout Albania since Illyrian times, they would have been, in the south, in more or less constant contact with the Greeks, and the absence or scarcity of definite loans from ancient Greek is hard to explain within the context of Albanian continuity. Even Greek loans into Illyrian are known (cf. Wilkes, et. al.; including Illyrian names borrowed from Greek), so their absence in Albanian as an alleged descendant of Illyrian as it was spoken in Albania is doubly difficult to explain.

Another problem is the ancient Illyrian and Roman toponyms (including hydronyms, etc.) in what is now Albania compared to their equivalents in the Albanian language. While a number may (most cases are contested among linguists) pose no major or definite problem in terms of linguistic evolution (v. Hemp), many others appear to have entered through one or more intermediary languages, which strongly indicates that the ancestors of Albanians were not in Albania (v. Hemp et. al.). For example, Albanian Shkodër from Latin Scodra and Albanian Tomor from Latin Tomarus do not match the Albanian phonological evolution (v. Hemp).

The written historical records pose another problem. The modern Albanians were not mentioned in Byzantine chronicles until 1043, although Illyria was part of the Byzantine Empire. The Illyrians are referred to for the last time as an ethnic group in Miracula Sancti Demetri (7th century AD).[15]

Thracian or Dacian origin

Aside from an Illyrian origin, a Dacian or Thracian origin is also hypothesized. There are a number of factors taken as evidence for a Dacian or Thracian origin of Albanians.

Albanian shares several hundred common words with Eastern Romance, these Eastern Romance words being part of the pre-Roman substrate (see: Eastern Romance substratum) and not loans; Albanian and Eastern Romance also share grammatical features (see Balkan language union) and phonological features, such as the common phonemes or the rhotacism of "n".[16]

Linguists such as Vladimir Georgiev have concluded that the phonology of the Dacian language is close to that of Albanian. However, the degree of this closeness has been criticized and challenged by other linguists, and it is based on incomplete evidence.[17] He suggests that Rumanian is a fully Romanised Dacian language, whereas Albanian is only partly so.

Cities whose names follow Albanian phonetic laws - such as Shtip (Štip), Shkupi (Skopje) and Niš - lie in the areas once inhabited by Thracians, Dardani,[18] and Paionians; however, Illyrians also inhabited or may have inhabited these regions, including Naissus. Hemp for example states that Naissus may as well be considered Illyrian territory.[19]

There are some close correspondences between Thracian and Albanian words.[15] However, as with Illyrian, most Dacian and Thracian words and names have not been closely linked with Albanian (v. Hemp). Also, many Dacian and Thracian placenames were made out of joined names (such as Dacian Sucidava or Thracian Bessapara; see List of Dacian cities and List of ancient Thracian cities), while the modern Albanian language does not allow this.[15]

There are no records that indicate a migration of Dacians into present day Albania. However, Thracian tribes such as the Bryges were present in Albania near Durrës since before the Roman conquest (v. Hemp).[15] An argument against a Thracian origin (which does not apply to Dacian) is that most Thracian territory was on the Greek half of the Jirecek Line, aside from varied Thracian populations stretching from Thrace into Albania, passing through Paionia and Dardania and up into Moesia; it is considered that most Thracians were Hellenized in Thrace (v. Hoddinott) and Macedonia.

Apart from linguistic theory that Albanian is more akin to eastern Romance (i.e. Dacian substrate) than western Roman (with Illyrian substrate- such as Dalmatian), Georgiev also notes that marine words in Albanian are borrowed from other languages, suggesting that Albanians were not originally a coastal people (as the Illyrians were). The absence of many Greek loan words also supports a Dacian theory - if Albanians originated in the region of Illyria there would surely be a heavy Greek influence.

The Dacian theory could also be consistent with the known patterns of barbarian incursions. Although there is no documentation of an Albanian migration (in fact there is no documentation of Albanians per se until the 11th century) the Morava valley region adjacent to Dacia was most heavily affected by migrations, thus making it plausible for its indigenous population to flee to, for example, the relative safety of mountainous northern Albania.

See also

- History of Albania

- Illyrians

- Prehistoric Balkans

- Paleo-Balkan languages

- Albanian nationalism

- Historiography and nationalism

- Illyrian language

- Origin of the Romanians

- Dacian language

- Thracian language

- Ethnogenesis

- Illyrian movement

References

- ^ Michele Belledi, Estella S. Poloni, Rosa Casalotti, Franco Conterio, Ilia Mikerezi, James Tagliavini and Laurent Excoffier. "Maternal and paternal lineages in Albania and the genetic structure of Indo-European populations". European Journal of Human Genetics, July 2000, Volume 8, Number 7, pp. 480-486. "Mitochondrial DNA HV1 sequences and Y chromosome haplotypes (DYS19 STR and YAP) were characterized in an Albanian sample and compared with those of several other Indo-European populations from the European continent. No significant difference was observed between Albanians and most other Europeans, despite the fact that Albanians are clearly different from all other Indo-Europeans linguistically. We observe a general lack of genetic structure among Indo-European populations for both maternal and paternal polymorphisms, as well as low levels of correlation between linguistics and genetics, even though slightly more significant for the Y chromosome than for mtDNA. Altogether, our results show that the linguistic structure of continental Indo-European populations is not reflected in the variability of the mitochondrial and Y chromosome markers. This discrepancy could be due to very recent differentiation of Indo-European populations in Europe and/or substantial amounts of gene flow among these populations."

- ^ Pritsak, Omeljan (1991). "Albanians". Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Vol. 1. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 52–53.

- ^ Thalloczy/Jirecek/Sufflay, Acta et diplomata res Albaniae mediae aetatis, Vindobonae, MCMXIII, I, 113 (1198).

- ^ Konstantin Jireček: Die Romanen in den Städten Dalmatiens während des Mittelalters, I, 42-44.

- ^ Comnena, Anna. The Alexiad, Book IV.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (1986). "Paulus Angelus". Dictionary of Albanian Literature. New York/Westport/London: Greenwood Press. p. 4.

- ^ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0631198075, p. 183. "We may begin with the Venetic peoples, Veneti, Carni, Histri and Liburni, whose language set them apart from the rest of the Illyrians."

- ^ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0631198075, p. 81. "In Roman Pannonia the Latobici and Varciani who dwelt east of the Venetic Catari in the upper Sava valley were Celtic but the Colapiani of the Colapis (Kulpa) valley were Illyrians..."

- ^ Thunmann, Johannes E. "Untersuchungen uber die Geschichte der Oslichen Europaischen Volger". Teil, Leipzig, 1774.

- ^ a b Jirecek, Konstantin. "The history of the Serbians" (Geschichte der Serben), Gotha, 1911

- ^ Vickers, Miranda. The Albanians. I.B. Tauris, 1999, ISBN 960-210-279-9, p. 196. "From time to time official lists were published with pagan, so-called Illyrian or freshly minted names considered appropriate for the new breed of revolutionary Albanians."

- ^ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0631198075, p. 219. "Not much reliance should perhaps be placed on attempts to identify an Illyrian anthropological type as short and dark-skinned similar to modern Albanians."

- ^ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0631198075, p. 278. "...likely identification seems to be with a Romanized population of Illyrian origin driven out by Slav settlements further north, the 'Romanoi' mentioned..."

- ^ The lack of ancient Greek loans in Albanian is disputed (see Hemp; Cabej). It is unanimously admitted, however, that if they are present, they are very rare (Hemp, Cabej).

- ^ a b c d Malcolm, Noel. "Kosovo, a short history". London: Macmillan, 1998, p. 22-40.

- ^ Eric P. Hamp, University of Chicago The Position of Albanian (Ancient IE dialects, Proceedings of the Conference on IE linguistics held at the University of California, Los Angeles, April 25-27, 1963, ed. By Henrik Birnbaum and Jaan Puhvel)

- ^ Duridanov, Ivan. "The Language of the Thracians", (Ezikyt na trakite), Nauka i izkustvo, Sofia, 1976.

- ^ It is disputed whether or not the Dardani can be considered Illyrians. However, the evidence indicates at least a strong Illyrian element.

- ^ Cabej, Eqrem. "Die aelteren Wohnsitze der Albaner auf der Balkanhalbinsel im Lichte der Sprache und Ortsnamen", Florence, 1961.

| History of Albania |

|---|

|

| Timeline |