Ernest Hemingway: Difference between revisions

Arcyqwerty (talk | contribs) Double redirect |

Arcyqwerty (talk | contribs) Link Mary Welsh Hemingway |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

===Cuba=== |

===Cuba=== |

||

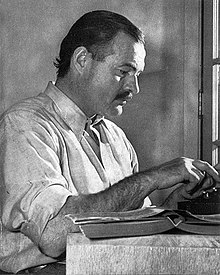

[[File:Hemingway 1953 Kenia.jpg|thumb|250px|Ernest Hemingway writing in Kenya in 1953 (JFK Library)]] |

[[File:Hemingway 1953 Kenia.jpg|thumb|250px|Ernest Hemingway writing in Kenya in 1953 (JFK Library)]] |

||

Of his writing career, Hemingway stated from 1942 to 1945 he "was out of business as a writer."<ref name="Mellow p552">qtd in {{Harvnb|Mellow|1992| p=552}}</ref> In 1946 he married Mary Welsh, who had an [[ectopic pregnancy]] five months later. Hemingway and Mary had a series of accidents and health problems after the war: in a 1945 car accident he "smashed his knee" and sustained another "deep wound on his forehead"; Mary broke her right ankle and then her left ankle in successive skiing accidents. In 1947 his sons Patrick and Gregory were in a car accident, leaving Patrick with a head wound and severely ill.<ref name="Meyers pp420–421">{{Harvnb|Meyers|1985| pp=420–421}}</ref> He became depressed as his literary friends died: in 1939 [[Yeats]] and Ford Madox Ford; in 1940 Scott Fitzgerald; in 1941 Sherwood Anderson and James Joyce; in 1946 Gertrude Stein; and the following year in 1947, Max Perkins, Hemingway's long time editor and friend.<ref name="Mellow pp548–550">{{Harvnb|Mellow|1992| pp=548–550}}</ref> During this period he had severe headaches, high blood pressure, weight problems, and eventually diabetes—much of which was the result of previous accidents and heavy drinking.<ref name="Desnoyers p12">{{Harvnb|Desnoyers| p=12}}</ref> Nonetheless, early in 1946 he began work on ''[[The Garden of Eden]]'' with 800 pages finished by June.<ref>{{Harvnb|Meyers|1985| p=436}}</ref><ref group=note>''[[The Garden of Eden]]'' was published posthumously in 1986.</ref> During the post–war years he also began work on a trilogy to be called "The Land", "The Sea" and "The Air" which he intended to combine in one novel known as ''The Sea Book''. However, both projects stalled and biographer James Mellow considers his inability to continue "a symptom of his troubles" during these years.<ref>{{Harvnb|Mellow|1992| p=552}}</ref><ref group=note>Published posthumously as ''[[Islands in the Stream]]'' in 1970.</ref> |

Of his writing career, Hemingway stated from 1942 to 1945 he "was out of business as a writer."<ref name="Mellow p552">qtd in {{Harvnb|Mellow|1992| p=552}}</ref> In 1946 he married [[Mary Welsh Hemingway|Mary Welsh]], who had an [[ectopic pregnancy]] five months later. Hemingway and Mary had a series of accidents and health problems after the war: in a 1945 car accident he "smashed his knee" and sustained another "deep wound on his forehead"; Mary broke her right ankle and then her left ankle in successive skiing accidents. In 1947 his sons Patrick and Gregory were in a car accident, leaving Patrick with a head wound and severely ill.<ref name="Meyers pp420–421">{{Harvnb|Meyers|1985| pp=420–421}}</ref> He became depressed as his literary friends died: in 1939 [[Yeats]] and Ford Madox Ford; in 1940 Scott Fitzgerald; in 1941 Sherwood Anderson and James Joyce; in 1946 Gertrude Stein; and the following year in 1947, Max Perkins, Hemingway's long time editor and friend.<ref name="Mellow pp548–550">{{Harvnb|Mellow|1992| pp=548–550}}</ref> During this period he had severe headaches, high blood pressure, weight problems, and eventually diabetes—much of which was the result of previous accidents and heavy drinking.<ref name="Desnoyers p12">{{Harvnb|Desnoyers| p=12}}</ref> Nonetheless, early in 1946 he began work on ''[[The Garden of Eden]]'' with 800 pages finished by June.<ref>{{Harvnb|Meyers|1985| p=436}}</ref><ref group=note>''[[The Garden of Eden]]'' was published posthumously in 1986.</ref> During the post–war years he also began work on a trilogy to be called "The Land", "The Sea" and "The Air" which he intended to combine in one novel known as ''The Sea Book''. However, both projects stalled and biographer James Mellow considers his inability to continue "a symptom of his troubles" during these years.<ref>{{Harvnb|Mellow|1992| p=552}}</ref><ref group=note>Published posthumously as ''[[Islands in the Stream]]'' in 1970.</ref> |

||

In 1948 Hemingway and Mary travelled to Europe. While visiting Italy he returned to the site of his World War I accident, and shortly afterwards he began work on ''[[Across the River and Into the Trees]]'', which he worked on through 1949; it was published in 1950 to bad reviews.<ref name="Meyers p453">{{Harvnb|Meyers|1985| p=440}}</ref> A year later he wrote the draft of ''[[Old Man and the Sea]]'' in eight weeks, considering it "the best I can write ever for all of my life".<ref name="Desnoyers p12"/> ''The Old Man and the Sea'' became a book-of-the month selection, made Hemingway an international celebrity, and won the [[Pulitzer Prize]] in May 1952, a month before he left for his second trip to Africa.<ref name = "Desnoyers p13">{{Harvnb|Desnoyers| p= 13}}</ref><ref name="Meyers p489">{{Harvnb|Meyers|1985| p=489}}</ref> |

In 1948 Hemingway and Mary travelled to Europe. While visiting Italy he returned to the site of his World War I accident, and shortly afterwards he began work on ''[[Across the River and Into the Trees]]'', which he worked on through 1949; it was published in 1950 to bad reviews.<ref name="Meyers p453">{{Harvnb|Meyers|1985| p=440}}</ref> A year later he wrote the draft of ''[[Old Man and the Sea]]'' in eight weeks, considering it "the best I can write ever for all of my life".<ref name="Desnoyers p12"/> ''The Old Man and the Sea'' became a book-of-the month selection, made Hemingway an international celebrity, and won the [[Pulitzer Prize]] in May 1952, a month before he left for his second trip to Africa.<ref name = "Desnoyers p13">{{Harvnb|Desnoyers| p= 13}}</ref><ref name="Meyers p489">{{Harvnb|Meyers|1985| p=489}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 01:24, 1 April 2010

Ernest Hemingway | |

|---|---|

Hemingway in 1939 | |

| Nationality | American |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1954 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction – 1953 |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (1921–1927) Pauline Pfeiffer (1927–1940) Martha Gellhorn (1940–1945) Mary Welsh Hemingway (1946–1961) |

| Children | Jack Hemingway (1923–2000) Patrick Hemingway (1928–) Gregory Hemingway (1931–2001) |

| Signature | |

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American writer and journalist. During his lifetime he had seven novels, six collections of short stories, and two works of non-fiction published, with a further three novels, four collections of short stories, and three non-fiction autobiographical works published after his death. Hemingway's distinctive writing style characterized by economy and understatement had an enormous influence on 20th-century fiction, as did his apparent life of adventure and the public image he cultivated. Hemingway produced most of his work between the mid-1920s and the mid-1950s, culminating in his 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature. Hemingway's protagonists are typically stoical men who exhibit an ideal described as "grace under pressure"; many of his works are considered classics of American literature.

Hemingway was born and raised in Oak Park, Illinois. After leaving high school he worked for a few months as a reporter, before leaving for the Italian front to become an ambulance driver during World War I; he was seriously wounded and returned home within the year. In 1922 Hemingway married Hadley Richardson, the first of his four wives, and the couple moved to Paris, where he worked as a foreign correspondent. During his time there he met and was influenced by writers and artists of the 1920s expatriate community known as the "Lost Generation". His first novel, The Sun Also Rises, was written in 1924.

After divorcing Hadley Richardson in 1927 Hemingway married Pauline Pfeiffer; they divorced following Hemingway's return from covering the Spanish Civil War, after which he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls. Martha Gellhorn became his third wife in 1940, but he left her for Mary Welsh Hemingway after World War II, during which he was present at D-Day and the liberation of Paris.

Shortly after the publication of The Old Man and the Sea in 1952 Hemingway went on safari to Africa, where he was almost killed in a plane crash that left him in pain or ill-health for much of the rest of his life. Hemingway had permanent residences in Key West, Florida, and Cuba during the 1930s and 40s, but in 1959 he moved from Cuba to Idaho, where he committed suicide in the summer of 1961.

Biography

Early life

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.[1] His father, Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, was a physician and his mother, Grace Hall–Hemingway (she hyphenated her last name), a musician, both well-educated and well-respected in the conservative community of Oak Park.[2] When Clarence and Grace Hemingway married in 1896, they moved in with Grace's father, Ernest Hall,[3] after whom they named their first son. Hemingway later claimed to dislike his given name, which he "associated with the naive, even foolish hero of Oscar Wilde's play The Importance of Being Earnest".[4] The family's seven–bedroom home in a respectable neighborhood contained a music studio for Grace and a medical office for Clarence.[5]

Hemingway's mother, a classically trained musician, frequently performed in concerts around the village. As an adult Hemingway professed to hate his mother, although biographer Michael Reynolds points out that Hemingway mirrored her energy and enthusiasm.[6] Her insistence that he learn the cello became a "source of conflict", but he admitted the music lessons were useful to his writing, as in the "contrapunctal structure of For Whom the Bell Tolls.[7] The family owned a summer home called Windemere on Walloon Lake, near Petoskey, Michigan, which they visited during the summers. There Hemingway learned to hunt, fish, and camp in the woods and lakes of Northern Michigan. His early experiences with nature instilled a lasting passion for outdoor adventure, living in remote or isolated areas, hunting and fishing.[8] His father Clarence instructed him in the outdoor life until depression caused him to become reclusive when Hemingway was about 12-years-old.[9]

Hemingway attended Oak Park and River Forest High School from 1913 until 1917. He took part in a number of sports—boxing, track, water polo, and football—and had good grades in English classes.[10] He and his sister Marcelline performed in the school orchestra for two years.[6] Beginning in his junior year, Hemingway wrote and edited the "Trapeze" and "Tabula" (the school's newspaper and yearbook), in which he imitated the language of sportswriters, and sometimes used the pen name Ring Lardner, Jr., a nod to his literary hero Ring Lardner of the Chicago Tribune, who used the byline "Line O'Type".[11] Like Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis, Hemingway worked as a journalist before becoming a novelist; after leaving high school he was hired as a cub reporter for The Kansas City Star,[12] where he quickly learned that the truth often lurks below the surface of a story.[13] Although he worked at the newspaper for only six months from October 17, 1917 to April 30, 1918, he relied on the Star's style guide as a foundation for his writing: "Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative."[14]

World War I

Early in 1918, Hemingway responded to a Red Cross recruitment effort and signed on as an ambulance driver. In the spring he returned for a quick trip home, and up to Michigan to fish, before leaving for New York.[15] He left New York in May, and arrived in Paris as the city was under bombardment from German artillery.[16] By June he was stationed at the Italian Front. The day he arrived in Milan he was dispatched to the scene of a munitions factory explosion where rescuers retrieved the shredded remains of the female workers.[17] A few days later he was stationed at Fossalta di Piave. On July 8 he was seriously wounded by mortar fire, having just returned from the canteen to deliver chocolate and cigarettes to the men at the front line.[18] Despite his wounds, Hemingway carried an Italian soldier to safety, for which he received the Italian Silver Medal of Bravery.[19] According to Hemingway scholar Hallengren, Hemingway "was the first American to be wounded during World War I".[20] Still only eighteen, Hemingway said of the incident: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you ... Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you."[21] He sustained shrapnel wounds to both legs; underwent an operation at a distribution center; spent five days at a field hospital; and was transferred to the Red Cross hospital in Milan for recuperation.[22] Hemingway spent six months in hospital, where he met and fell in love with Agnes von Kurowsky, a Red Cross nurse seven years his senior.[23] Agnes and Hemingway planned to marry, but she became engaged to an Italian officer in March 1919, an incident that provided material for the short and bitter work "A Very Short Story".[24] Biographer Jeffrey Meyers claims Hemingway was devastated by Agnes' rejection, and that he followed a pattern of abandoning a wife before she abandoned him in future relationships. During his six months in recuperation Hemingway met and formed a strong friendship with "Chink" Dorman-Smith which was to endure for decades.[25]

Toronto and Chicago

Hemingway returned home in early 1919 and spent the summer in Michigan, fishing and camping with high school friends.[21] In September he left for the back country with two friends to fish and camp for a week. The trip became the inspiration for his short story "Big Two-Hearted River", in which Nick Adams takes to the country to find solitude after his return from war.[26] Late in the year he moved to Toronto and began to write for the Toronto Star Weekly as a freelancer, staff writer, and foreign correspondent.[27] In the fall of 1920, after having spent the summer in Michigan,[27] he moved to Chicago for a short period while still filing stories for the Toronto Star. In Chicago he worked as associate editor of the monthly journal Co-operative Commonwealth and met Hadley Richardson, eight years older than him (and one year older than Agnes).[28] After a few months Hadley and Hemingway decided to marry, planning a honeymoon in Europe; Sherwood Anderson convinced them to visit Paris, a city quickly attracting expatriate artists largely because of the good exchange rates.[29] Hemingway married Hadley on September 3, 1921. Two months later Hemingway became a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star and the couple left for Paris.[30]

Paris

Anderson wrote letters of introduction for Hemingway to Gertrude Stein and other writers in Paris.[31] Stein, who became Hemingway's mentor for a period and introduced him to the Expatriate Modernists of the Montparnasse Quarter, referred to the young artists as the "Lost Generation" a term Hemingway popularized with the publication of The Sun Also Rises.[32] A regular at Stein's salon, Hemingway met young and newly influential artists such as Pablo Picasso, Joan Miro, and Juan Gris.[33] Eventually Hemingway withdrew from Stein's influence and their relationship deteriorated into a literary quarrel that spanned decades.[34] During this period Ezra Pound mentored the young writer.[33] Hemingway met Pound in February 1922, toured Italy with him in 1923, and lived on the same street in 1924. The two forged a strong friendship, and in Hemingway Pound recognized, and fostered, a talented writer.[35] A popular gathering place for writers was Sylvia Beach's Shakespeare and Company. She published James Joyce's Ulysses, and Hemingway met Joyce there in March 1922. The two writers frequently embarked on "alcoholic sprees".[36] Hemingway and Hadley lived in a small walk-up on the Rue de Cardinal Lemoine, and he worked in a rented room in a nearby building.[29]

During his first 20 months in Paris, Hemingway filed 88 stories for the Toronto Star.[37] He covered the Greco-Turkish War where he witnessed the burning of Smyrna; he wrote travel pieces such as "Tuna Fishing in Spain", "Trout Fishing All Across Europe: Spain Has the Best, Then Germany"; and he wrote about bullfighting—"Pamplona in July; World's Series of Bull Fighting a Mad, Whirling Carnival".[38] Hemingway was devastated on learning that Hadley had lost a suitcase filled with his manuscripts at the Gare de Lyons as she was travelling to Geneva to meet him in December 1922.[39] A month later, because Hadley was pregnant, the couple returned to Toronto, where their son John Hadley Nicanor was born on October 10, 1923. During their absence Hemingway's first book was published, Three Stories and Ten Poems. Two of the stories it contained were all that remained of his work after the loss of the suitcase, and the third had been written the previous spring in Italy. Within months a second volume, in our time (without capitals), was published. The small volume included six vignettes and a dozen stories Hemingway had written the previous summer during his first visit to Spain. Hadley, Hemingway, and their son (nicknamed Bumby), returned to Paris in January 1924 and moved into a new apartment on the Rue Notre Dame des Champs.[40] Hemingway helped Ford Madox Ford edit The Transatlantic Review, in which works by Pound, John Dos Passos, and Gertrude Stein were published, as well as some of Hemingway's own early stories such as "Indian Camp".[41] When "In Our Time" (with capital letters) was published in 1925 the dust jacket had comments from Ford.[42][43] Six months earlier, Hemingway met F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the pair formed a friendship of "admiration and hostility".[44]

In the summer of 1925, Hemingway and Hadley went on their annual visit to Pamplona for the Festival of San Fermín, accompanied by a group of American and British ex-patriates.[45] The trip inspired Hemingway's first novel, The Sun Also Rises, which he began to write immediately after the fiesta, finishing it September.[46] He decided to slow down for the revision process and devoted all of that fall and winter to the rewrite.[47] The revised manuscript arrived in New York in April,[48] and Hemingway corrected the final proof in Paris in August 1926.[49] Scribner's published the novel in October.[50]

Hemingway's marriage to Hadley broke down as he was writing and revising The Sun Also Rises.[49] In the spring of 1926, Hadley became aware of his affair with Pauline Pfeiffer,[51] although she had endured Pauline's presence in Pamplona that July.[52] However, on their return to Paris Hadley and Hemingway decided to separate,[53] and Hadley formally requested a divorce in the fall. By November they had split their possessions, and Hadley accepted Hemingway's offer of the proceeds from The Sun Also Rises.[54] The couple were divorced in January 1927, and Hemingway married Pauline Pfeiffer in May.[55]

Pauline was from Arkansas—her family was wealthy and Catholic—and before their marriage Hemingway converted to Catholicism.[56][57] In Paris she worked for Vogue.[56] After a honeymoon in Grau-du-Roi, where he contracted anthrax, Hemingway settled in Paris and planned his next collection of short stories,[58] Men Without Women, published in October 1927.[59] By the end of the year Pauline was pregnant, and wanted to move back to America to have her baby. John Dos Passos recommended Key West; in March 1928, they left Paris. Some time that spring Hemingway suffered a severe injury in their Paris bathroom, when he pulled a skylight down on his head thinking he was pulling on a toilet chain. This left him with a prominent forehead scar, subject of numerous legends, which he carried for the rest of his life. When Hemingway was asked about the scar he was reluctant to answer.[60][note 1] After his departure from Paris, Hemingway "never again lived in a big city".[61]

Key West and the Caribbean

In the late spring Hemingway and Pauline travelled to Kansas City where their son Patrick Hemingway was born on June 28, 1928. Pauline had a difficult delivery, which Hemingway fictionalized in A Farewell to Arms.[62] After Patrick's birth, Pauline and Hemingway travelled to Wyoming, Massachusetts and New York.[62] In the fall he was in New York with Bumby, about to board a train to Florida, when he received a cable telling him that his father had committed suicide.[note 2][63]

Hemingway worked on the draft of A Farewell to Arms during 1928. It was finished by late summer, but he delayed for a few months before revising it. By the winter of 1929 the serialization in Scribner's magazine was set for May, but that spring Hemingway continued to work on the book's ending in France, which he may have rewritten as many as seventeen times. When the book was published on September 27[64] Hemingway's stature as an American writer was secured.[65] In France and Spain during the summer of 1929 he gathered material for his next work, Death in the Afternoon.[66]

During the early 1930s Hemingway spent his winters in Key West and summers in Wyoming, where he found "the most beautiful country he had seen in the American West" and hunting that included deer, elk, and grizzly bear. His third son, Gregory Hancock Hemingway, was born on November 12, 1931 in Kansas City.[67][note 3] Pauline's uncle bought the couple a house in Key West where the second floor of the carriage house was converted to a writing den.[68] While in Key West he enticed his male friends to join him on fishing expeditions—inviting his longtime friends Waldo Peirce, John Dos Passos, and Max Perkins[69]—with one all male trip to the Dry Tortugas, and he relaxed at Sloppy Joe's.[70]

In 1933 Hemingway and Pauline went on safari to East Africa, a 10-week trip that provided material for Green Hills of Africa as well as the short stories "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber".[71] They visited Mombasa, Nairobi, and Machakos in Kenya, then Tanganyika where they hunted in the Serengeti, around Lake Manyara and west and southeast of the present-day Tarangire National Park. Hemingway contracted amoebic dysentery that caused a prolapsed intestine and he was evacuated by plane to Nairobi, an experience reflected in "The Snows of Kilimanjaro". Their guide was the noted "white hunter" Philip Hope Percival, who had guided Theodore Roosevelt on his 1909 safari. On his return to Key West in early 1934 Hemingway began work on Green Hills of Africa, published in 1935 to mixed reviews.[72]

Back in Key West, Hemingway bought a boat in 1934, named it the Pilar, and began sailing the Caribbean.[73] In 1935 he discovered Bimini, where he spent a considerable amount of time.[71] During this period he also worked on To Have and Have Not, published in 1937 while he was in Spain, the only novel he wrote during the 1930s.[74]

Spanish Civil War and World War II

In 1937 Hemingway reported on the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA).[75] He arrived in France in March, and in Spain ten days later with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens.[76] Ivens, who was filming The Spanish Earth, needed Hemingway as a screenwriter to replace John Dos Passos, who left the project when his friend José Robles was arrested and later executed.[77] The incident changed Dos Passos' opinion of the republicans, which created a rift between him and Hemingway, who spread a rumor that Dos Passos was a coward for leaving Spain.[78]

Journalist Martha Gellhorn, whom Hemingway met in Key West in 1936, joined him in Spain.[79] While in Madrid with Gellhorn, Hemingway wrote the play The Fifth Column during the bombardment of Madrid late in 1937.[80] He returned to Key West for a few months, then back to Spain in 1938 where he was present at the Battle of the Ebro, the last republican stand. With fellow British and American journalists, Hemingway rowed the group across the river, some of the last to leave the battle.[81][82]

Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn moved to Cuba in 1939, and in 1940 bought the "Finca Vigia" ("Lookout Farm"), which they had been renting. A few months later Hemingway divorced Pauline and married Martha.[83] As he had after his divorce from Hadley, he changed locations: he moved his primary summer residence to Ketchum, Idaho, just outside the newly built resort of Sun Valley; and his winter residence to Cuba.[84] He was at work on For Whom the Bell Tolls, which he started in March 1939, finished in July 1940, and was published in October 1940.[85] Consistent with his pattern of moving around while working on a manuscript, he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls in Cuba, Wyoming, and Sun Valley.[86] For Whom the Bell Tolls became a book-of-the-month choice, sold half a million copies within months, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and became a literary triumph for Hemingway.[87]

In January 1941 Martha was sent to China on assignment for Collier's magazine, and Hemingway accompanied her. Although Hemingway wrote dispatches for PM, he had little affinity for China.[88] However, in the recently-published Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America, co-written by John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr and Alexander Vassilev, it is alleged that Hemingway's KGB file identifies him as "Agent Argo". He was apparently recruited in 1941 before the trip to China, but he ultimately failed to "give [the Russians] any political information" and was not "verified in practical work". Contact with "Argo" ceased by 1950.[89]

Hemingway returned to Cuba on the outbreak of World War II, and refitted the Pilar to hunt down German submarines.[21] From June to December 1944 he was in Europe, at the D-Day landing after which he attached himself to "the 22nd Regiment commanded by Col. Charles 'Buck' Lanaham as it drove toward Paris", and he led a small band of village militia in Rambouillet outside of Paris.[90] Of Hemingway's exploits, War II historian Paul Fussell remarks: "Hemingway got into considerable trouble playing infantry captain to a group of Resistance people that he gathered because a correspondent is not supposed to lead troops, even if he does it well".[21] On August 25 he was present at the liberation of Paris, although the assertion that he was first in the city, or that he liberated the Ritz is considered part of the Hemingway legend.[91][92] While in Paris he attended a reunion hosted by Sylvia Beach and made up his long-running feud with Gertrude Stein.[93] Hemingway was present at heavy fighting in the Hürtgenwald at the end 1944.[94]

When Hemingway arrived in Europe, he met Time magazine correspondent Mary Welsh in London.[95] During the war his marriage to Martha disintegrated; the last time he saw her was in March 1945 as he was preparing to return to Cuba.[96] In 1947 Hemingway was awarded a Bronze Star for his bravery during World War II. His valor for having been "under fire in combat areas in order to obtain an accurate picture of conditions" was recognized, with the commendation that "through his talent of expression, Mr. Hemingway enabled readers to obtain a vivid picture of the difficulties and triumphs of the front-line soldier and his organization in combat".[21]

Cuba

Of his writing career, Hemingway stated from 1942 to 1945 he "was out of business as a writer."[97] In 1946 he married Mary Welsh, who had an ectopic pregnancy five months later. Hemingway and Mary had a series of accidents and health problems after the war: in a 1945 car accident he "smashed his knee" and sustained another "deep wound on his forehead"; Mary broke her right ankle and then her left ankle in successive skiing accidents. In 1947 his sons Patrick and Gregory were in a car accident, leaving Patrick with a head wound and severely ill.[98] He became depressed as his literary friends died: in 1939 Yeats and Ford Madox Ford; in 1940 Scott Fitzgerald; in 1941 Sherwood Anderson and James Joyce; in 1946 Gertrude Stein; and the following year in 1947, Max Perkins, Hemingway's long time editor and friend.[99] During this period he had severe headaches, high blood pressure, weight problems, and eventually diabetes—much of which was the result of previous accidents and heavy drinking.[100] Nonetheless, early in 1946 he began work on The Garden of Eden with 800 pages finished by June.[101][note 4] During the post–war years he also began work on a trilogy to be called "The Land", "The Sea" and "The Air" which he intended to combine in one novel known as The Sea Book. However, both projects stalled and biographer James Mellow considers his inability to continue "a symptom of his troubles" during these years.[102][note 5]

In 1948 Hemingway and Mary travelled to Europe. While visiting Italy he returned to the site of his World War I accident, and shortly afterwards he began work on Across the River and Into the Trees, which he worked on through 1949; it was published in 1950 to bad reviews.[103] A year later he wrote the draft of Old Man and the Sea in eight weeks, considering it "the best I can write ever for all of my life".[100] The Old Man and the Sea became a book-of-the month selection, made Hemingway an international celebrity, and won the Pulitzer Prize in May 1952, a month before he left for his second trip to Africa.[104][105]

In Africa he was seriously injured in two successive plane crashes: he sprained his right shoulder, arm, and left leg; had a concussion; temporarily lost vision in his left eye and the hearing in his left ear; suffered paralysis of the spine; had a crushed vertebra, ruptured liver, spleen and kidney; and sustained first degree burns on his face, arms, and leg. Some American newspapers published his obituary, believing he had been killed. A month later he was again badly injured in a bushfire accident, which left him with second degree burns on his legs, front torso, lips, left hand and right forearm.[106]

Back in Cuba, in October 1954 Hemingway received the Nobel Prize in Literature. Politely he mentioned Carl Sandburg and Isak Dinesen, who in his opinion, deserved the prize. The prize money was welcome, he told reporters.[107] Because he was in pain as a result of the African accidents, and he had recently returned home to Cuba after an absence of almost a year, Hemingway chose not to travel to Stockholm to accept the prize in person.[108] Instead he sent a speech to be read in which he defines the writer's life: "Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer's loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day."[109][note 6]

As a result of the severe accidents and injuries he sustained in Africa, Hemingway was bedridden from late 1956 to early 1957.[110] The Finca Vigia became crowded with guests and tourists and Hemingway, beginning to become unhappy with life in Cuba, considered a permanent move to Idaho. In 1959 he bought a home overlooking the Big Wood River, outside of Ketchum, and left Cuba, although he apparently remained on easy terms with the Castro government, going so far as telling the New York Times he was "delighted" with Castro's overthrow of Havana.[111][112] In 1960, he left Cuba and Finca Vigía for the last time. The house was appropriated after the Bay of Pigs Invasion (two months before Hemingway's death), complete with Hemingway's collection of "four to six thousand books", and the Hemingways were forced to leave art and manuscripts in a bank vault in Havana.[113]

Idaho and suicide

In 1957 he had begun A Moveable Feast, working on it in Cuba and Idaho from 1957 to 1960.[114][115] His early passion for bullfighting was renewed in 1959 when he spent the summer in Spain for a series of bullfighting articles he was to write for Life Magazine.[116] The following winter the manuscript grew to 63,000 words—Life wanted only 10,000 words—and he asked his friend A. E. Hotchner to help organize the manuscript that was to become The Dangerous Summer.[117][118] Although Hemingway's mental deterioration began to be noticeable in the summer of 1960, he travelled to Spain to gather photographs for the manuscript. Alone in Spain, without Mary, Hemingway's mental state disintegrated rapidly. The first installments of The Dangerous Summer were published in Life in September 1960 to good reviews. When he left Spain, Hemingway travelled straight to Idaho; that November he was admitted to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.[119] He had been receiving treatment for high blood pressure and liver problems, and he may have believed he was going to be treated for hypertension.[120] His paranoia became acute and he believed the FBI was actively monitoring his movements.[121] [note 7] Hemingway suffered from physical problems as well: his eyesight was failing; his health was poor. Furthermore, his home and possessions in Cuba had been abandoned during the revolution.[122]

Back in Ketchum in the spring of 1961, three months after his initial ECT treatments at the Mayo, Hemingway attempted suicide. Mary asked Hemingway's personal physician, Dr. Saviers, for immediate hospitalization at the Sun Valley hospital; and from there he was returned to the Mayo for more shock treatments.[123] He was released in late June and arrived home in Ketchum on June 30. Two days later, in the early morning hours of July 2, 1961, Hemingway "quite deliberately" shot himself with his favorite shotgun.[124]

Other members of Hemingway's immediate family also committed suicide: his father Clarence Hemingway; his sister Ursula; and his brother Leicester.[125] During his final years, Hemingway's behavior was similar to his father's before he committed suicide.[126] Hemingway's father may have had the genetic disease haemochromatosis, in which the inability to metabolize iron culminates in mental and physical deterioration.[127] Medical records made available in 1991 confirm that Hemingway's haemochromatosis had been diagnosed early in 1961.[128] Added to his physical ailments was the additional problem that Hemingway had been a heavy drinker for most of his life.[100]

Hemingway is interred at the Ketchum Cemetery, at the north end of town. A memorial was erected in 1966 at another location, overlooking Trail Creek, north of Ketchum. On it is inscribed a eulogy Ernest Hemingway wrote for a friend, Gene Van Guilder:

Best of all he loved the fall

The leaves yellow on the cottonwoods

Leaves floating on the trout streams

And above the hills

The high blue windless skies

Now he will be a part of them forever

Ernest Hemingway – Idaho – 1939

Themes

Leslie Fiedler believes themes recurrent in American literature exist with great clarity in Hemingway's work. A theme Fiedler defines as "The Sacred Land"—the American West—is extended in Hemingway's work to include the mountains of Spain, Switzerland and Africa, and the streams of Michigan. The American West is symbolized by the use of the "Hotel Montana" in The Sun Also Rises and in For Whom the Bell Tolls. Furthermore, Fiedler considers the American literary theme of the evil "Dark Woman" vs. the good "Light Woman" to be inverted in Hemingway's fiction. The dark woman (Brett Ashley) is a goddess; the light woman (Margot Macomber) is a murderess.[129]

The theme of death permeates Hemingway's work. Stoltzfus believes Hemingway's writings exhibit the concept of existentialism: redemption is possible at the moment of death if the concept of "nothingness" is embraced. When death is faced with dignity and courage then life can be lived with authenticity. In Hemingway's works those who live an "authentic" life find redemption at the moment of death. Francis Macomber dies happy because the last hours of his life are authentic; the bullfighter in the corrida represents the pinnacle of a life lived with authenticity.[130]

Although Hemingway writes about sports, Carlos Baker claims the emphasis is not on sport but on the athlete.[131] According to Stoltzfus the hunter or fisherman has a moment of transcendence when the prey is killed. Nature is a place for rebirth, for therapy, as in "The Big Two-Hearted River".[130] Nature is the great refuge, according to Fiedler. Nature is where men are without women: men fish; men hunt; men find redemption in nature.[129]

Finally the theme of emasculation is prevalent, most notably in The Sun Also Rises in which Jake Barnes's war wound—and his inability to consummate the relationship with Brett—contributes to the tension of the piece. Emasculation, according to Fiedler, is both a result of a generation of wounded soldiers, but of more importance, a generation in which women such as Brett gained emancipation.[129] Baker believes Hemingway's work emphasizes the "natural" vs. the "unnatural". For example, the short story "Alpine Idyll" is about the "unnaturalness" of skiers in the high country where the late spring snow is juxtaposed against the "unnaturalness" of the peasant who allowed his wife's dead body to linger too long in the shed during the winter. The skiers and peasant retreat to the valley to the "natural" spring for redemption.[132]

Writing style

The New York Times wrote in 1926 of Hemingway's first novel: "No amount of analysis can convey the quality of The Sun Also Rises. It is a truly gripping story, told in a lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame".[133] The Sun Also Rises is written in the spare, tightly written prose for which Hemingway is famous, a style which has influenced countless crime and pulp fiction novels.[134] It is a style which some critics consider his greatest contribution to literature.[135] In 1954, when Hemingway was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature it was for "his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style".[136]

Henry Louis Gates believes Hemingway's style was fundamentally shaped post–World War I. He explains that Hemingway and other modernists "lost faith in the central institutions of Western civilization" and as a reaction against the "elaborate style" of 19th century writers, Hemingway created a style "in which meaning is established through dialogue, through action, and silences—a fiction in which nothing crucial—or at least very little—is stated explicitly."[21]

| If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing. |

| —Ernest Hemingway in Death in the Afternoon [137] |

Hemingway began as a writer of short stories, and as Baker explains, he learned how to "get the most from the least, how to prune language how to multiply intensities, and how to tell nothing but the truth in a way that allowed for telling more than the truth".[138] The style is known as the Iceberg Theory because in Hemingway's writing the hard facts float above water; the supporting structure, complete with symbolism, operates out-of-sight.[138] Jackson Benson believes Hemingway used autobiographical details to work as framing devices to write about life in general—not only about his life. For example, Benson postulates that Hemingway used his experiences and drew them out further with "what if" scenarios: "what if I were wounded in such a way that I could not sleep at night? What if I were wounded and made crazy, what would happen if I were sent back to the front?"[139] The concept of the iceberg theory is sometimes referred to as the "theory of omission." Hemingway believed the writer could describe one thing (such as Nick Adams fishing in "The Big Two-Hearted River") though an entirely different thing occurs below the surface (Nick Adams concentrating on fishing to the extent that he does not have to think about anything else).[140]

The simplicity of the prose is deceptive. Zoe Trodd believes Hemingway crafted skeletal sentences in response to Henry James's observation that WWI had "used up words". In his writing Hemingway offered an almost photographic reality that was often "multi-focal". His iceberg theory of omission was the foundation on which he built. The syntax, which lacks subordinating conjunctions, creates static sentences. He used a photographic "snapshot" style to create a collage of images. Short sentences build one on another; events build to create a sense of the whole. Multiple strands exist in one story; an "embedded text" bridges to a different angle. He also used other cinematic techniques of "cutting" quickly from one scene to the next; or of "splicing" a scene into another. Intentional omissions allow the reader to fill the gap, as though responding to instructions from the author, and create three-dimensional prose.[141]

Hemingway uses polysyndeton to convey both a timeless immediacy and a Biblical grandeur. Hemingway's polysyndetonic sentence—or, in later works, his use of subordinate clauses—uses conjunctions to juxtapose startling visions and images; the critic Jackson Benson compares them to haikus.[135][142] Many of Hemingway's acolytes misinterpreted his lead and frowned upon all expression of emotion; Saul Bellow satirized this style as "Do you have emotions? Strangle them."[143] However, Hemingway's intent was not to eliminate emotion but to portray it more scientifically. Hemingway thought it would be easy, and pointless, to describe emotions; he sculpted his bright and finely chiseled collages of images in order to grasp "the real thing, the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion and which would be as valid in a year or in ten years or, with luck and if you stated it purely enough, always".[144] This use of an image as an objective correlative is characteristic of Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, and of course Proust.[145][note 8] Hemingway's letters refer to Proust's Remembrance of Things Past several times over the years, and indicate he might have read the massive book at least twice.[146] His writing was likely also influenced by the Japanese poetic canon.[147][note 9]

Influence and legacy

Hemingway's most important legacy to American literature is his style: writers who came after him attempted either to emulate it or to avoid it.[148] In a 2004 speech at the John F. Kennedy Library, Russell Banks declared that he, like many male writers of his generation, was influenced by Hemingway's philosophy of the writing process, Hemingway's style, and Hemingway's life and public image.[149] With the publication of The Sun Also Rises Hemingway's reputation was sealed. He became the spokesperson for the post-World War I generation, and he established a style to be emulated.[134] His books were burned in Berlin in 1933, and disavowed by his parents.[20] Hemingway biographer Michael Reynolds asserts Hemingway's legacy is that "he left stories and novels so starkly moving that some have become part of our cultural heritage."[150]

Jackson Benson claims Hemingway, and the details of his life, have become a "prime vehicle for exploitation" which has created a "Hemingway industry".[151] The "hard boiled style" that is often used to describe Hemingway's work should not be confused with the author, according to Hemingway scholar Hallengren, who considers the machismo of the man should be separated from the author himself.[20] Benson agrees, going so far as to point out that Hemingway was as introverted and private as J. D. Salinger, yet paradoxically, Hemingway masked his true nature with braggadacio.[152] In fact, during World War II, Salinger met and corresponded with Hemingway, whom he acknowledged as an influence.[153] In a letter to Hemingway, Salinger wrote that their talks "had given him his only hopeful minutes of the entire war", and jokingly "named himself national chairman of the Hemingway Fan Clubs".[154]

The extent of Hemingway's influence is seen in the many tributes to the man, and echoes of his fiction to be found in popular culture. The International Imitation Hemingway Competition was created in the 1980s to publicly acknowledge his influence, and the comically misplaced efforts of lesser authors to imitate his style. Entrants are encouraged to submit one "really good page of really bad Hemingway", and winners are flown to Italy to Harry's Bar there.[155] In 1978 a minor planet, discovered in 1978 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh, was named for him—3656 Hemingway;[156] on July 17, 1989, the United States Postal Service issued a 25-cent postage stamp honoring Hemingway.[157]; Ray Bradbury wrote the story The Kilimanjaro Device in which Hemingway doesn't die, but instead is transported to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro, which represents a heaven for writers, according to Hemingway's own story "The Snows of Kilimanjaro";[67] the 1993 motion picture Wrestling Ernest Hemingway, about the friendship of two retired men, one Irish, one Cuban, in a seaside town in Florida, starred Robert Duvall, Richard Harris, Shirley MacLaine, Sandra Bullock, and Piper Laurie.[158] Furthermore, Hemingway's influence is evident in popular culture with the existence of many restaurants named "Hemingway"; and the proliferation of bars called "Harry's" (a nod to the bar in Across the River and Into the Trees).[159] A line of "Hemingway" furniture, introduced by a popular manufacturer and promoted by Hemingway's son Jack (Bumby), has pieces such as the "Kilimanjaro" bedside table.[160]

Family

- Parents

- Father: Clarence Hemingway. Born September 2, 1871, died December 6, 1928. (death by suicide)

- Mother: Grace Hall Hemingway. Born June 15, 1872, died June 28, 1951

- Siblings

- Marcelline Hemingway. Born January 15, 1898, died December 9, 1963

- Ursula Hemingway. Born April 29, 1902, died October 30, 1966 (death by suicide)

- Madelaine Hemingway. Born November 28, 1904, died January 14, 1995

- Carol Hemingway. Born July 19, 1911, died October 27, 2002

- Leicester Hemingway. Born April 1, 1915, died September 13, 1982 (death by suicide)

- Wives, children and grandchildren

- Elizabeth Hadley Richardson. Married September 3, 1921, divorced April 4, 1927, died January 22, 1979.

- Son, John Hadley Nicanor "Jack" Hemingway (aka Bumby). Born October 10, 1923, died December 1, 2000.

- Granddaughter, Joan (Muffet) Hemingway

- Granddaughter, Margaux Hemingway. Born February 16, 1954, died July 2, 1996 (death by suicide)

- Granddaughter, Mariel Hemingway. Born November 22, 1961

- Great-Granddaughter, Dree Hemingway. Born 1987

- Pauline Pfeiffer. Married May 10, 1927, divorced November 4, 1940, died October 21, 1951.

- Son, Patrick Hemingway. Born June 28, 1928.

- Granddaughter, Mina Hemingway

- Son, Gregory Hemingway (called 'Gig' by Hemingway; later called himself 'Gloria'). Born November 12, 1931, died October 1, 2001.

- Grandchildren, Patrick, Edward, Sean, Brendan, Vanessa, Maria, Adiel, John Hemingway and Lorian Hemingway

- Martha Gellhorn. Married November 21, 1940, divorced December 21, 1945, died February 15, 1998.

- Mary Welsh. Married March 14, 1946, died November 26, 1986.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ In the April 1931 passport application, Hemingway noted the forehead scar. In 1928, the skylight in the bathroom of his Paris apartment fell on him, which caused one of the many head injuries he received throughout his life.

- ^ Clarence Hemingway used his father's Civil War pistol to shoot himself.Meyers 1985, p. 2

- ^ Gregory Hemingway underwent sex reassignment surgery in the mid-1990s and thereafter was known as Gloria Hemingway BBC News. 3 October 2003. Hemingway legacy feud 'resolved'. Accessed 2010–19–02.

- ^ The Garden of Eden was published posthumously in 1986.

- ^ Published posthumously as Islands in the Stream in 1970.

- ^ The full spech is available at Nobelprize.org

- ^ In fact, the FBI had opened a file on him during WWII, when he used the Pilar to patrol the waters off Cuba, and J. Edgar Hoover had an agent in Havana watch Hemingway during the 1950s.(Mellow 1992, pp. 597–598) The FBI knew Hemingway was at the Mayo, as an agent documented in a letter written in January, 1961.(Meyers 1985, pp. 543–544)

- ^ McCormick compares Hemingway's and Proust's use of memory to find the objective correlative

- ^ Starrs draws a correlation between the "Imagist" influences of Ezra Pound, who mentored Hemingway in the 1920s.

Footnotes

- ^ Oliver, p. 140

- ^ Reynolds 2000, p. 17

- ^ Oliver, p. 134

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 8

- ^ Reynolds 2000, pp. 17–18

- ^ a b Reynolds 2000, p. 19

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 3

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 13

- ^ Reynolds 2000, p. 20

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 21

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 19

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 23

- ^ Reynolds 1998, p. 17

- ^ "Star style and rules for writing". The Kansas City Star. KansasCity.com. Retrieved 2009–08–29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 48–49

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 27

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 57

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 59–60

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 30–31

- ^ a b c Hallengren

- ^ a b c d e f Putnam

- ^ Desnoyers, p. 3

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 37

- ^ Scholes harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFScholes (help)

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 40–42

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 101

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, pp. 51–53

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 56–58

- ^ a b Baker 1972, p. 7

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 60–62

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 61

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 308

- ^ a b Reynolds 2000, p. 28

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 77–81

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 73–74

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 82

- ^ Reynolds, p. 24

- ^ Desnoyers, p. 5

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 69–70

- ^ Baker 1972, pp. 15–18

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 126

- ^ Baker 1972, p. 34

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 127

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 159–160

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 119

- ^ Baker 1972, pp. 33–34

- ^ Baker 1972, p. 34

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 328

- ^ a b Baker 1972, p. 44

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 189

- ^ Baker 1972, p. 43

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 333

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 338

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 340

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 172

- ^ a b Mellow 1992, p. 294

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 174

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 348–353

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 195

- ^ Robinson, Daniel (2005). ""My True Occupation is That of a Writer:Hemingway's passport correspondence". The Hemingway Review. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 204

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 208

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 367

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 215

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 378

- ^ Baker 1972, pp. 96–98

- ^ a b Oliver, p. 144

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 222–227

- ^ Mellow 1992

- ^ Mellow 1985, p. 402

- ^ a b Desnoyers, p. 9

- ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 337–340

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 280

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 292

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 488

- ^ Koch 2005, p. 87

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 311

- ^ Koch 2005, p. 164

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 298

- ^ Koch 2005, p. 134

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 321

- ^ Thomas 2001, p. 833

- ^ Desnoyers, pp. 10–11

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 342

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 334

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 326

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 335–338

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 356–361

- ^ Dugdale, John (2009-07-09). "Hemingway revealed as failed KGB spy". The Guardian. Retrieved 2010–02–08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 398–405

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 408

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 535

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 541

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 411

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 394

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 416

- ^ qtd in Mellow 1992, p. 552

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 420–421

- ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 548–550

- ^ a b c Desnoyers, p. 12

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 436

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 552

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 440

- ^ Desnoyers, p. 13

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 489

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 505–507

- ^ Baker 1972, p. 338

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 509

- ^ "Ernest Hemingway The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954 Banquet Speech". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 512

- ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 494–495

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 516–519

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 599

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 533

- ^ Hotchner, A.E. (2009–07–19). "Don't Touch 'A Movable Feast'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009–09–3.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Meyers 1985, p. 520

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 542

- ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 598–600

- ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 598–601

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 545

- ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 597–598

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 543–544

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 551

- ^ Reynolds 2000, p. 16

- ^ Oliver, pp. 139–149

- ^ Burwell 1996, p. 234

- ^ Burwell 1996, p. 14

- ^ Burwell 1996, p. 189

- ^ a b c Fiedler, p. 345–365

- ^ a b Stoltzfus

- ^ Baker, p. 101-121

- ^ Baker, pp. 101–121

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ a b Nagel 1996, p. 87

- ^ a b McCormick, p. 49

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ qtd. in Oliver 1999, p. 322

- ^ a b Baker 1972, p. 117

- ^ Benson 1989

- ^ Oliver 1999, pp. 321–322

- ^ Trodd

- ^ Benson, p. 309

- ^ qtd. in Hoberek, p. 309

- ^ Hemingway: Death in the Afternoon, Chapter 1 Excerpt Simon & Schuster Books website. Retrieved 09-03-2010.

- ^ McCormick, p. 47

- ^ Burwell 1996, p. 187

- ^ Starrs, Roy (1998). An Artless Art. The Japan Library. p. 77. ISBN 1–873410–64–6. Retrieved 2010–02–09.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Oliver 1999, pp. 140–141

- ^ Banks, p. 54

- ^ Reynolds 2000, p. 15

- ^ Benson 1989, p. 347

- ^ Benson 1989, p. 349

- ^ Lamb, Robert Paul (Winter 1996). "Hemingway and the creation of twentieth-century dialogue – American author Ernest Hemingway" (reprint). Twentieth Century Literature. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ^ Baker, Carlos (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 420, 646. ISBN 0-02-001690-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Wanted: One Really Good Page of Really Bad Hemingway Jack Smith. LA Times, March 15, 1993. Retrieved 07-03-2010.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 307. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Scott catalog # 2418;

- ^ Oliver, p. 360

- ^ Oliver, p. 142

- ^ A Line of Hemingway Furniture, With a Veneer of Taste Jan Hoffman, The New York Times, June 15, 1999. Retrieved 09-03-2010.

Bibliography

- Baker, Carlos (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-02-001690-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Baker, Carlos (1972). Hemingway: The Writer as Artist (4th ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01305-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|note=ignored (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Baker, Carlos, ed. (1981). Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters 1917–1961. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-16765-4.

- Banks, Russell (2004). "PEN/Hemingway Prize Speech". The Hemingway Review. 24 (1): 53–60.

- Jackson J., Benson, ed. (1990). "Decoding Papa: "A Very Short Story" as Work and Text". New Critical Approaches to the short stories of Ernest Hemingway. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1067-8. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help); Text "Decoding Papa" ignored (help); Text "in New Critical Approaches" ignored (help) - Benson, Jackson (1989). "Ernest Hemingway: The Life as Fiction and the Fiction as Life". American Literature. 61 (3): 345–358.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Benson, Jackson J. (1975). The short stories of Ernest Hemingway: critical essays. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-0320-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Burwell, Rose Marie. Hemingway: the postwar years and the posthumous novels. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 189. ISBN 0–521–48199–6. Retrieved 2009–12–11.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Desnoyers, Megan Floyd. "Ernest Hemingway: A Storyteller's Legacy". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Online Resources. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hoberek, Andrew (2005). Twilight of the Middle Class:Post World War II fiction and White Collar Work. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-691-12145-1.

{{cite book}}: Text "2005" ignored (help) - Hallengren, Anders (28 August 2001). "A Case of Identity: Ernest Hemingway". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- Koch, Stephen (2005). The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles. New York: Counterpoint. pp. 87–164. ISBN 1-58243-280-5. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - McCormick, John. American Literature 1919–1932. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul. Retrieved 2009–12–13.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Mellow, James R. (1992). Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-37777-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Benson, Jackson, ed. (1996). "Brett and the Other Women in the Sun Also Rises". The Cambridge Companion to Ernest Hemingway. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45479-X. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - Lingeman, Richard (April 25, 1972). "More Posthumous Hemingway". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- Oliver, Charles M. (1999). Ernest Hemingway A to Z: The Essential Reference to the Life and Work. New York: Checkmark. ISBN 0-8160-3467-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Ondaatje, Christopher (30 October 2001). "Bewitched by Africa's strange beauty". The Independent. independent.co.uk. Retrieved 2009–09–16.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Reynolds, Michael S. (1998). The Young Hemingway. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-31776-5. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Reynolds, Michael S. (1997). Hemingway: The 1930s. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-31778-1. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Wagner-Martin, Linda, ed. (2000). "Ernest Hemingway: A Brief Biography". A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512151-1. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - Putnam, Thomas (2006). "Hemingway on War and Its Aftermath". The National Archives. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- Raeburn, John (1998). "Hemingway on Stage: The Fifth Column, Politics and Biography". The Hemingway Review. 18 (1): 5–16.

- Jackson J., Benson, ed. (1990). "Decoding Papa: "A Very Short Story" as Work and Text". New Critical Approaches to the short stories of Ernest Hemingway. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1067-8. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - Stoltzfus, Ben (2005). "Sartre, "Nada," and Hemingway's African Stories". Comparative Literature Studies. 42 (3): 250–228.

- Thomas, Hugh (2001). The Spanish Civil War. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-375-75515-2. Retrieved 2009-9–18.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Trodd, Zoe (2007). "Hemingway's camera eye: The problems of language and an interwar politics of form". The Hemingway Review. 26 (2): 7–21.

External links

- Hemingway Archives: John F. Kennedy Library

- The Charles D. Field Collection of Ernest Hemingway(call number M0440; 1.25 linear ft) are housed in the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at *Stanford University Libraries

- The Hemingway Society

- Template:Worldcat id

- Ernest Hemingway's Collection at The University of Texas at Austin

- 1899 births

- 1961 deaths

- American essayists

- American expatriates in Canada

- American expatriates in Cuba

- American expatriates in France

- American expatriates in Italy

- American expatriates in Spain

- American hunters

- American journalists

- American Nobel laureates

- American memoirists

- American military personnel of World War I

- American novelists

- American people of the Spanish Civil War

- American short story writers

- American socialists

- Anti-fascists

- American people of English descent

- Ernest Hemingway

- History of Key West, Florida

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- Operation Overlord people

- People from Oak Park, Illinois

- Pulitzer Prize for Fiction winners

- Recipients of the Silver Medal of Military Valor

- Suicides by firearm in Idaho

- War correspondents

- Writers from Chicago, Illinois

- Writers who committed suicide