Sodium: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 70.178.21.52 (talk) to last version by Sbharris |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{about|the chemical element|the PlayStation Home game|Sodium (PlayStation Home)}} |

{{about|the chemical element|the PlayStation Home game|Sodium (PlayStation Home)}} |

||

{{ |

{{Info box sodium}} |

||

'''Sodium''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|s|oʊ|d|i|ə|m}} {{respell|SOH|dee-əm}}) is a [[chemical element]] with the symbol '''Na''' (from {{lang-la|natrium}}) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal and is a member of the [[alkali metals]]; its only stable [[isotope]] is <sup>23</sup>Na. It is an abundant element that exists in numerous minerals such as [[feldspar]]s, [[sodalite]] and [[halite|rock salt]]. Many salts of sodium are highly soluble in water and are thus present in significant quantities in the Earth's bodies of water, most abundantly in the oceans as [[sodium chloride]]. |

'''Sodium''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|s|oʊ|d|i|ə|m}} {{respell|SOH|dee-əm}}) is a [[chemical element]] with the symbol '''Na''' (from {{lang-la|natrium}}) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal and is a member of the [[alkali metals]]; its only stable [[isotope]] is <sup>23</sup>Na. It is an abundant element that exists in numerous minerals such as [[feldspar]]s, [[sodalite]] and [[halite|rock salt]]. Many salts of sodium are highly soluble in water and are thus present in significant quantities in the Earth's bodies of water, most abundantly in the oceans as [[sodium chloride]]. |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

==Characteristics== |

==Characteristics== |

||

===Physical=== |

===Physical=== |

||

[[File:Na-D-sodium D-lines-589nm.jpg|thumb|left|[[Emission spectrum]] for sodium, showing the |

[[File:Na-D-sodium D-lines-589nm.jpg|thumb|left|[[Emission spectrum]] for sodium, showing the |

||

[[File:Flametest--Na.swn.jpg|thumb|left|upright|A positive [[flame test]] for sodium has a bright yellow color.]] |

[[File:Flametest--Na.swn.jpg|thumb|left|upright|A positive [[flame test]] for sodium has a bright yellow color.]] |

||

Revision as of 19:57, 20 January 2012

Template:Info box sodium Sodium (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈsoʊdiəm/ SOH-dee-əm) is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin: natrium) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal and is a member of the alkali metals; its only stable isotope is 23Na. It is an abundant element that exists in numerous minerals such as feldspars, sodalite and rock salt. Many salts of sodium are highly soluble in water and are thus present in significant quantities in the Earth's bodies of water, most abundantly in the oceans as sodium chloride.

Many sodium compounds are useful, such as sodium hydroxide (lye) for soapmaking, and sodium chloride for use as a deicing agent and a nutrient. Sodium is an essential element for all animals and some plants. In animals, sodium ions are used against potassium ions to build up charges on cell membranes, allowing transmission of nerve impulses when the charge is dissipated; it is therefore classified as a dietary inorganic macro-mineral.

The free metal, elemental sodium, does not occur in nature but must be prepared from sodium compounds. Elemental sodium was first isolated by Humphry Davy in 1807 by the electrolysis of sodium hydroxide. The same ion is also a component of many minerals, such as sodium nitrate.

Characteristics

Physical

[[File:Na-D-sodium D-lines-589nm.jpg|thumb|left|Emission spectrum for sodium, showing the [[File:Flametest--Na.swn.jpg|thumb|left|upright|A positive flame test for sodium has a bright yellow color.]]

Sodium at STP is a soft metal that can be readily cut with a knife and is a good conductor of electricity. Freshly exposed sodium has a bright, silvery luster that rapidly tarnishes and forms a white oxide layer. These properties change at elevated pressures: at 1.5 Mbar, the color changes to black, then to red transparent at 1.9 Mbar, and finally clear transparent at 3 Mbar. All of these allotropes are insulators and electrides.[1]

When sodium or its compounds are introduced into a flame, they turn it yellow,[2] because the heat excites sodium atoms and moves their valence electrons from the 3s orbital to the 3p orbital; as those electrons fall back to 3s, they emit a photon with a wavelength corresponding to the D line at 589.3 nm. Spin-orbit interactions of the valence electron in the 3p orbital cause the D line to split into the D1 (589.6 nm) and D2 (589.0 nm) lines; hyperfine structures of both orbitals lead to many more lines.[3][4][5] A practical use for lasers emitting light at the D line is to create artificial laser guide stars that assist in the adaptive optics for large land-based visible light telescopes.

Chemical

Sodium metal is highly reducing, with the reduction of sodium ions requiring −2.71 volts;[6] other alkali metals have more negative potentials. Hence, the extraction of sodium metal from its compounds (such as with sodium chloride) uses a significant amount of energy.[7] In terms of handling properties, sodium is generally less reactive than potassium and more reactive than lithium.[8] Like all the alkali metals, it reacts exothermically with water, to the point that sufficiently large pieces melt to a sphere and then explode; this reaction produces caustic sodium hydroxide and flammable hydrogen gas. When burned in dry air, it mainly forms sodium peroxide as well as some sodium oxide. In moist air, sodium hydroxide results.[7]

Isotopes

20 isotopes of sodium are known, but only 23Na is stable. Two radioactive, cosmogenic isotopes are the byproduct of cosmic ray spallation: 22Na with a half-life of 2.6 years and 24Na with a half-life of 15 hours; all other isotopes have a half-life of less than one minute.[9] Two nuclear isomers have been discovered, the longer-lived one being 24mNa with a half-life of around 20.2 microseconds. Acute neutron radiation, such as from a nuclear criticality accident, converts some of the stable 23Na in human blood to 24Na; by measuring the concentration of 24Na in relation to 23Na, the neutron radiation dosage of the victim can be calculated.[10]

Occurrence

23Na is created in the carbon-burning process by fusing two carbon atoms together; this requires temperatures above 600 megakelvins and a star with at least three solar masses.[11] The Earth's crust has 2.6% sodium by weight, making it the sixth most abundant element there.[12] Because of its high reactivity, it is never found as a pure element. It is found in many different minerals, some very soluble, such as halite and natron, others much less soluble such as amphibole, and zeolite. The insolubility of certain sodium minerals such as cryolite and feldspar arises from their polymeric anions, which in the case of feldspar is a polysilicate. In the interstellar medium, sodium is identified by the D line; though it has a high vaporization temperature, its abundance allowed it to be detected by Mariner 10 in Mercury's atmosphere.[13]

Compounds

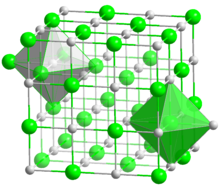

Sodium compounds are of immense commercial importance, being particularly central to industries producing glass, paper, soap, and textiles.[14] The sodium compounds that are the most important are common salt (NaCl), soda ash (Na2CO3), baking soda (NaHCO3), caustic soda (NaOH), sodium nitrate (NaNO3), di- and tri-sodium phosphates, sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3·5H2O), and borax (Na2B4O7·10H2O).[15] In its compounds, sodium is usually ionically bonded to water and anions, and is viewed as a hard Lewis acid.[16]

Aqueous solutions

Sodium tends to form water-soluble compounds, such as halides, sulfates, nitrates, carboxylates and carbonates. The main species in water are the aquo complexes [Na(H2O)n]+ where n = 4–6.[17]

The high affinity of sodium for oxygen-based ligands is the basis of crown ethers. Functionally related but more complex ligands are several macrolide antibiotics, which function by interfering with the transport of Na+ in the infecting organism.

The precipitation of sodium salts from water solution is uncommon because sodium salts typically have a high affinity for water. An illustrative sodium salt exhibiting low solubility in water is sodium bismuthate (NaBiO3).[18] Since sodium salts are so soluble in water, they are usually isolated as solids by evaporation of these aqueous solutions or by precipitation with an organic solvent. For example, 360 g of sodium chloride will dissolve in one litre of water at room temperature. The addition of ethanol to such solutions can cause solid NaCl to separate (precipitate), because only 0.35 g/litre of sodium chloride will dissolve in the alcohol.[19]

Related to sodium compounds' good water solubility, these compounds do not dissolve well in organic solvents. Crown ethers, especially 15-crown-5 may be used as a phase-transfer catalyst.

Analysis

Bulk sodium content may be determined by treating a sample with a large excess of uranyl zinc acetate; uranyl zinc sodium acetate precipitates as the hexahydrate ((UO2)2ZnNa(CH3CO2)·6H2O), and its mass can be weighed (see gravimetry). The presence of caesium and rubidium does not interfere with this reaction, but the potassium and lithium must be removed prior to analysis.[20][21]

Lower concentrations of sodium may be determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry,[22] and by potentiometry using ion-selective electrodes.[23][24]

Electrides and sodides

Like the other alkali metals, metallic sodium dissolves in ammonia and some other amines to give deeply coloured solutions. Evaporation of these solutions leaves a shiny film of metallic sodium. The solutions contain the coordination complex [Na(NH3)6]+ ions, whose positive charge is counterbalanced by electrons as anions. Using organic ligands called cryptands, these salts, called electrides, can be isolated as crystalline solids. Cryptands, like crown ethers and other ionophores, have high affinity for Na+. Electrides have the formula [Na(2,2,2-crypt)]+e−. Using similar techniques, one can also obtain derivatives of Na-. Thus, salts containing the "sodide" anion form by the addition of cryptands to solutions of sodium in ammonia via the chemical reaction called disproportionation:[25]

- 2 Na + 2,2,2-crypt → [Na(2,2,2-crypt)]+Na−

Sodide is an example of an alkalide, rare compounds where the alkali metal exists in a negative oxidation state. These ions have a filled 4s shell.

Organosodium compounds

Many organosodium compounds have been prepared. Because of the high polarity of the C-Na bonds, they behave like sources of carbanions (salts with organic anions). Some well known derivatives include sodium cyclopentadienide (NaC5H5) and trityl sodium ((C6H5)3CNa).[26]

History

Salt has been an important commodity in human activities, as shown by the English word salary, which derives from salarium, the wafers of salt sometimes given to Roman soldiers along with their other wages. In medieval Europe, a compound of sodium with the Latin name of sodanum was used as a headache remedy. The name sodium is thought to originate from the Arabic suda, meaning headache, as the headache-alleviating properties of sodium carbonate or soda were well known in early times.[27] The chemical abbreviation for sodium was first published by Jöns Jakob Berzelius in his system of atomic symbols,[28] and is a contraction of the element's new Latin name natrium, which refers to the Egyptian natron,[27] a natural mineral salt primarily made of hydrated sodium carbonate. Natron historically had several important industrial and household uses, later eclipsed by other sodium compounds. Although sodium, sometimes called soda, had long been recognised in compounds, the metal itself was not isolated until 1807 by Humphry Davy through the electrolysis of sodium hydroxide.[29][30]

Sodium imparts an intense yellow color to flames. As early as 1860, Kirchhoff and Bunsen noted the high sensitivity of a sodium flame test, and stated in Annalen der Physik und Chemie:[31]

In a corner of our 60 m3 room farthest away from the apparatus, we exploded 3 mg. of sodium chlorate with milk sugar while observing the nonluminous flame before the slit. After a while, it glowed a bright yellow and showed a strong sodium line that disappeared only after 10 minutes. From the weight of the sodium salt and the volume of air in the room, we easily calculate that one part by weight of air could not contain more than 1/20 millionth weight of sodium.

Commercial production

Enjoying rather specialized applications, only about 100,000 tonnes of metallic sodium are produced annually.[14] Metallic sodium was first produced commercially in 1855 by carbothermal reduction of sodium carbonate at 1100 °C, in what is known as the Deville process:[32][33][34]

- Na2CO3 + 2 C → 2 Na + 3 CO

A related process based on the reduction of sodium hydroxide was developed in 1886.[32]

Sodium is now produced commercially through the electrolysis of molten sodium chloride, based on a process patented in 1924.[35][36] This is done in a Downs Cell in which the NaCl is mixed with calcium chloride to lower the melting point below 700 °C. As calcium is less electropositive than sodium, no calcium will be formed at the anode. This method is less expensive than the previous Castner process of electrolyzing sodium hydroxide.

Reagent-grade sodium in tonne quantities sold for about US$3.30/kg in 2009; lower purity metal sells for considerably less. The market for sodium is volatile due to the difficulty in its storage and shipping; it must be stored under a dry inert gas atmosphere or anhydrous mineral oil to prevent the formation of a surface layer of sodium oxide or sodium superoxide. These oxides can react violently in the presence of organic materials. Sodium will also burn violently when heated in air.[37] Smaller quantities of sodium cost far more, in the range of US$165/kg; the high cost is partially due to the expense of shipping hazardous material.[38]

Applications

Though metallic sodium has some important uses, the major applications of sodium use it in its many compounds; millions of tons of the chloride, hydroxide, and carbonate are produced annually.

Free element

Metallic sodium is mainly used for the production of sodium borohydride, sodium azide, indigo, and triphenylphosphine. Previous uses were for the making of tetraethyllead and titanium metal; because applications for these chemicals were discontinued, the production of sodium declined after 1970.[14] Sodium is also used as an alloying metal, an anti-scaling agent,[39] and as a reducing agent for metals when other materials are ineffective. Sodium vapor lamps are often used for street lighting in cities and give colours ranging from yellow-orange to peach as the pressure increases.[40] By itself or with potassium, sodium is a desiccant; it gives an intense blue colouration with benzophenone when the desiccate is dry.[41] In organic synthesis, sodium is used in various reactions such as the Birch reduction, and the sodium fusion test is conducted to qualitatively analyse compounds.[42] Many important medicines have sodium added to improve their bioavailability.[14]

Heat transfer

Liquid sodium is used as a heat transfer fluid in some fast reactors,[44] due to its high thermal conductivity and low neutron absorption cross section, which is required to achieve a high neutron flux; the high boiling point allows the reactor to operate at ambient pressure. Drawbacks of using sodium include its opacity, which hinders visual maintenance, and its explosive properties. Radioactive sodium-24 may be formed by neutron activation during operation, posing a slight radiation hazard; the radioactivity stops within a few days after removal from the reactor. If a reactor needs to be frequently shut down, NaK is used; due to it being liquid at room temperature, cooling pipes do not freeze. In this case, the pyrophoricity of potassium means extra precautions against leaks need to be taken.

A different heat transfer application is in internal combustion engines with poppet valves. In high performance engines sometimes sodium-cooled valve stems are used to cool the valves. These hollow valve stems are partially filled with sodium and act as a heat pipe.

Compounds

Most soaps are sodium salts of fatty acids. Sodium soaps are harder (higher melting) soaps than potassium soaps.[15] Sodium chloride is extensively used for anti-icing and de-icing as well as and as a preservative; sodium bicarbonate is mainly used for cooking.

Biological role

Sodium is an essential nutrient that regulates blood volume, blood pressure, osmotic equilibrium and pH; the minimum physiological requirement for sodium is 500 milligrams per day.[45] Sodium chloride is the principal source of sodium in the diet, and is used as seasoning and preservative, such as for pickling and jerky; most of it comes from processed foods.[46] The DRI for sodium is 2.3 grams per day,[47] but on average people in the United States consume 3.4 grams per day,[48] the minimum amount that promotes hypertension;[49] this in turn causes 7.6 million premature deaths worldwide.[50]

The renin-angiotensin system and the atrial natriuretic peptide regulate the amount of fluid in the body. Reduction of blood pressure and sodium concentration in the kidney result in the production of renin, which in turn produces aldosterone, retaining sodium in the urine. Because of this, the osmotic pressure changes and osmoregulation systems generate the antidiuretic hormone, causing the body to retain water and restore its total amount of fluid. Receptors in the heart and blood vessels sense the resulting distension and pressure, leading to production of the atrial natriuretic peptide, causing the body to lose sodium in the urine; the osmoregulation systems detect this and remove water, restoring the total fluid levels.

Sodium is also important in neuron function and osmoregulation between cells and the extracellular fluid; their distribution is mediated in all animals by Na+/K+-ATPase.[51] Hence, sodium is the most prominent cation in extracellular fluid: the 15 liters of it in a 70 kg human have around 50 grams of sodium, 90% of the body's total sodium content.

In C4 plants, sodium is a micronutrient that aids in metabolism, specifically in regeneration of phosphoenolpyruvate and synthesis of chlorophyll.[52] In others, it substitutes for potassium in several roles, such as maintaining turgor pressure and aiding in the opening and closing of stomata.[53] Excess sodium in the soil limits the uptake of water due to decreased water potential, which may result in wilting; similar concentrations in the cytoplasm can lead to enzyme inhibition, which in turn causes necrosis and chlorosis.[54] To avoid these problems, plants developed mechanisms that limit sodium uptake by roots, store them in cell vacuoles, and control them over long distances;[55] excess sodium may also be stored in old plant tissue, limiting the damage to new growth.

Precautions

Care is required in handling elemental sodium, as it is potentially explosive and generates flammable hydrogen and caustic sodium hydroxide upon contact with water; powdered sodium may combust spontaneously in air or oxygen.[56] Excess sodium can be safely removed by hydrolysis in a ventilated cabinet; this is typically done by sequential treatment with isopropanol, ethanol and water. Isopropanol reacts very slowly, generating the corresponding alkoxide and hydrogen.[57] Fire extinguishers based on water accelerate sodium fires; those based on carbon dioxide and bromochlorodifluoromethane lose their effectiveness when they dissipate. An effective extinguishing agent is Met-L-X, which comprises approximately 5% Saran in sodium chloride together with flow agents; it is most commonly hand-applied with a scoop. Other materials include Lith+, which has graphite powder and an organophosphate flame retardant, and dry sand.

See also

References

- ^ Gatti, M.; Tokatly, I.; Rubio, A. (2010). "Sodium: A Charge-Transfer Insulator at High Pressures". Physical Review Letters. 104 (21): 216–404. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104u6404G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.216404.

- ^ Schumann, Walter (5 August 2008). Minerals of the World (2nd ed.). Sterling. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4027-5339-8. OCLC 637302667.

- ^ Citron, M. L.; Gabel, C.; Stroud, C.; Stroud, C. (1977). "Experimental study of power broadening in a two level atom". Physical Review A. 16 (4): 1507. Bibcode:1977PhRvA..16.1507C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.16.1507.

- ^ Steck, Daniel A. "Sodium D. Line Data" (PDF). Los Alamos National Laboratory (technical report).

- ^ Milonni, Peter W.; Eberly, Joseph H. (12 June 2009). "Laser Physics": 118–120. ISBN 9780470387719.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Atkins, Peter W.; de Paula, Julio (2002). Physical Chemistry (7th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 9780716735397. OCLC 3345182.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ De Leon, N. "Reactivity of Alkali Metals". Indiana University Northwest. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

- ^ Audi, Georges (2003). "The NUBASE Evaluation of Nuclear and Decay Properties". Nuclear Physics A. 729. Atomic Mass Data Center: 3–128. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- ^ Sanders, F. W.; Auxier, J. A. (1962). "Neutron Activation of Sodium in Anthropomorphous Phantoms". HealthPhysics. 8 (4): 371–379. doi:10.1097/00004032-196208000-00005. PMID 14496815.

- ^ Denisenkov, P. A.; Ivanov, V. V. (1987). "Sodium Synthesis in Hydrogen Burning Stars". Soviet Astronomy Letters. 13: 214. Bibcode:1987SvAL...13..214D.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Tjrhonsen, Dietrick E. (17 August 1985). "Sodium found in Mercury's atmosphere". BNET. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ^ a b c d Alfred Klemm, Gabriele Hartmann, Ludwig Lange, "Sodium and Sodium Alloys" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_277

- ^ a b Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). "Natrium". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 931–943. ISBN 3-11-007511-3.

- ^ Cowan, James A. (1997). Inorganic Biochemistry: An Introduction. Wiley-VCH. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-471-18895-7. OCLC 34515430.

- ^ "Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II". 2004: 515. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043748-6/01055-0. ISBN 978-0-08-043748-4.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dean, John Aurie; Lange, Norbert Adolph (1998). Lange's Handbook of Chemistry. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070163847.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Burgess, J. (1978). Metal Ions in Solution. New York: Ellis Horwood. ISBN 0-85312-027-7.

- ^ Barber, H. H.; Kolthoff, I. M. (1928). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 50 (6): 1625. doi:10.1021/ja01393a014.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Barber, H. H.; Kolthoff, I. M. (1929). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 51 (11): 3233. doi:10.1021/ja01386a008.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Kingsley, GR; Schaffert, RR (1954). "Micro flame photometric determination of sodium, potassium and calcium in serum with solvents". J. Biol. Chem. 206 (2): 807–15. PMID 13143043.

- ^ Levy, G. B. (1981). "Determination of sodium with ion-selective electrodes". Clinical Chemistry. 27 (8): 1435–1438. PMID 7273405.

- ^ "ASTM D2791 – 07 Standard Test Method for On-line Determination of Sodium in Water" (Document). ASTM international. 2007. doi:10.1520/D2791-07.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. "Inorganic Chemistry" Academic Press: San Diego, 2001. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ^ Hauser, W. B. (1943). "Triphenylmethylsodium". Organic Syntheses

{{cite journal}}:|given2=missing|surname2=(help); Collected Volumes, vol. 2, p. 607. - ^ a b Newton, David E. (1999). Baker, Lawrence W. (ed.). Chemical Elements. ISBN 978-0-7876-2847-5. OCLC 39778687.

- ^ van der Krogt, Peter. "Elementymology & Elements Multidict". Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ Davy, Humphry (1808). "On some new phenomena of chemical changes produced by electricity, particularly the decomposition of the fixed alkalies, and the exhibition of the new substances which constitute their bases; and on the general nature of alkaline bodies". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 98: 1–44. doi:10.1098/rstl.1808.0001.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements. IX. Three alkali metals: Potassium, sodium, and lithium". Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (6): 1035. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9.1035W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1035.

- ^ Kirchhoff, G.; Bunsen, R. (1860). "Chemische Analyse durch Spectralbeobachtungen". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 186 (6): 161–189. Bibcode:1860AnP...186..161K. doi:10.1002/andp.18601860602.

- ^ a b Eggeman, Tim; Updated By Staff (2007). "Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology". John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1915040912051311.a01.pub3. ISBN 0471238961.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Oesper, R. E.; Lemay, P. (1950). "Henri Sainte-Claire Deville, 1818–1881". Chymia. 3: 205–221. JSTOR 27757153.

- ^ Banks, Alton (1990). "Sodium". Journal of Chemical Education. 67 (12): 1046. Bibcode:1990JChEd..67.1046B. doi:10.1021/ed067p1046.

- ^ Pauling, Linus, General Chemistry, 1970 ed., Dover Publications

- ^ "Los Alamos National Laboratory – Sodium". Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ "Sodium Metal 99.97% Purity". Galliumsource.com. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "007-Sodium Metal". Mcssl.com. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Harris, Jay C. (1949). Metal cleaning: bibliographical abstracts, 1842–1951. American Society for Testing and Materials. p. 76. OCLC 1848092.

- ^ Lindsey, Jack L. (1997). Applied illumination engineering. Fairmont Press. pp. 112–114. ISBN 978-0-88173-212-2. OCLC 22184876.

- ^ Lerner, Leonid (16 February 2011). Small-Scale Synthesis of Laboratory Reagents with Reaction Modeling. CRC Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-1-4398-1312-6. OCLC 669160695.

- ^ Sethi, Arun (1 January 2006). Systematic Laboratory Experiments in Organic Chemistry. New Age International. pp. 32–35. ISBN 978-81-224-1491-2. OCLC 86068991.

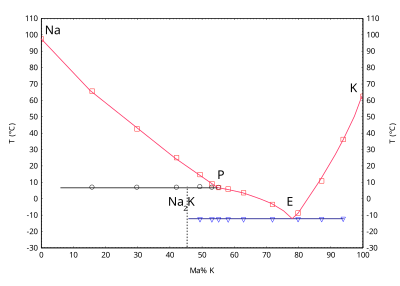

- ^ van Rossen, G. L. C. M.; van Bleiswijk, H. (1912). "Über das Zustandsdiagramm der Kalium-Natriumlegierungen". Zeitschrift für anorganische Chemie. 74: 152–156. doi:10.1002/zaac.19120740115.

- ^ Sodium as a Fast Reactor Coolant presented by Thomas H. Fanning. Nuclear Engineering Division. U.S. Department of Energy. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Topical Seminar Series on Sodium Fast Reactors. May 3, 2007

- ^ "Sodium" (PDF). Northewestern University. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "Sodium and Potassium Quick Health Facts". Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ "Dietary Reference Intakes: Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate". Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, United States National Academies. 11 February 2004. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2010). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (PDF) (7th ed.). p. 22. ISBN 9780160879418. OCLC 738512922. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Geleijnse, J. M.; Kok, F. J.; Grobbee, D. E. (2004). "Impact of dietary and lifestyle factors on the prevalence of hypertension in Western populations". European Journal of Public Health. 14 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1093/eurpub/14.3.235. PMID 15369026.

- ^ Lawes, C. M.; Vander Hoorn, S.; Rodgers, A.; International Society of Hypertension (2008). "Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001" (PDF). Lancet. 371 (9623): 1513–1518. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. PMID 18456100.

- ^ Campbell, Neil (1987). Biology. Benjamin/Cummings. p. 795. ISBN 0-8053-1840-2.

- ^ Kering, M. K. (2008). "Manganese Nutrition and Photosynthesis in NAD-malic enzyme C4 plants Ph.D. dissertation" (PDF). University of Missouri-Columbia. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Subbarao, G. V.; Ito, O.; Berry, W. L.; Wheeler, R. M. (2003). "Sodium—A Functional Plant Nutrient". Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 22 (5): 391–416. doi:10.1080/07352680390243495.

- ^ Zhu, J. K. (2001). "Plant salt tolerance". Trends in plant science. 6 (2): 66–71. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01838-0. PMID 11173290.

- ^ "Plants and salt ion toxicity". Plant Biology. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Sodium Lake Explosion 1". Video.google.de. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Angelici, R. J. (1999). Synthesis and Technique in Inorganic Chemistry. Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books. ISBN 0935702482.

External links

- Template:PeriodicVideo

- Etymology of "natrium" – source of symbol Na

- The Wooden Periodic Table Table's Entry on Sodium

- Dietary Sodium

- Sodium isotopes data from The Berkeley Laboratory Isotopes Project's