Animism: Difference between revisions

Melodychick (talk | contribs) m →See also: clean up |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:AnimismSymbolWhite.PNG|thumb|right|200px|Symbol of animism]] |

|||

'''Animism''' (from [[Latin]] ''anima'' "[[Soul (spirit)|soul]], [[life]]")<ref name = "ooviqc">Segal, p. 14.</ref><ref>"Animism", ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', p. 72.</ref> refers to the belief that non-human entities are spiritual beings, or at least embody some kind of life-principle.<ref>{{cite book|author=Iannone, A. Pablo|chapter=animism|title=Dictionary of world philosophy|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2001|isbn=9780415179959|page=54|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=7wBmBO3vpE4C&pg=PA54}}</ref> |

'''Animism''' (from [[Latin]] ''anima'' "[[Soul (spirit)|soul]], [[life]]")<ref name = "ooviqc">Segal, p. 14.</ref><ref>"Animism", ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', p. 72.</ref> refers to the belief that non-human entities are spiritual beings, or at least embody some kind of life-principle.<ref>{{cite book|author=Iannone, A. Pablo|chapter=animism|title=Dictionary of world philosophy|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2001|isbn=9780415179959|page=54|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=7wBmBO3vpE4C&pg=PA54}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 10:02, 22 February 2012

Animism (from Latin anima "soul, life")[1][2] refers to the belief that non-human entities are spiritual beings, or at least embody some kind of life-principle.[3]

Animism encompasses the beliefs that there is no separation between the spiritual and physical (or material) world, and souls or spirits exist, not only in humans, but also in all other animals, plants, rocks, natural phenomena such as thunder, geographic features such as mountains or rivers, or other entities of the natural environment.[4] Animism may further attribute souls to abstract concepts such as words, true names, or metaphors in mythology. Animism is particularly widely found in the religions of indigenous peoples,[5] including Shinto, and some forms of Hinduism, Buddhism, Pantheism, Paganism, and Neopaganism.

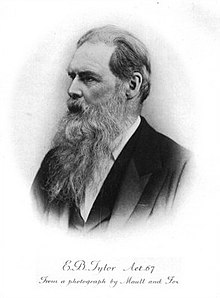

Throughout European history, philosophers such as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, among others, contemplated the possibility that souls exist in animals, plants, and people; however, the currently accepted definition of animism was only developed in the 19th century by Sir Edward Tylor, who created it as "one of anthropology's earliest concepts, if not the first".[5]

According to the anthropologist Tim Ingold, animism shares similarities to totemism but differs in its focus on individual spirit beings which help to perpetuate life, whereas totemism more typically holds that there is a primary source, such as the land itself or the ancestors, who provide the basis to life. Certain indigenous religious groups such as the Australian Aborigines are more typically totemic, whereas others like the Inuit are more typically animistic in their worldview.[6]

Etymology

The term animism appears to have been first developed as animismus by German scientist Georg Ernst Stahl, circa 1720, to refer to the "doctrine that animal life is produced by an immaterial soul." The actual English language form of animism, however, can only be attested to 1819.[7] The term was taken and redefined by the anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor in his 1871 book Primitive Culture, in which he defined it as "the general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general."[8] According to religious scholar Robert Segal, Tylor saw all religions, "modern and primitive alike", as forms of animism.[1]

According to Tylor, animism often includes "an idea of pervading life and will in nature";[9] i.e., a belief that natural objects other than humans have souls. As a self-described "confirmed scientific rationalist", Tylor believed that this view was "childish" and typical of "cognitive underdevelopment",[10] and that it was therefore common in "primitive" peoples such as those living in hunter gatherer societies.

Tylor's definition of animism has since largely been followed by anthropologists, such as Émile Durkheim, Claude Lévi-Strauss and Tim Ingold. However, some anthropologists, such as Nurit Bird-David, have criticised the Tylorian concept of animism, believing it to be outdated.[11]

Motivation

Animism in the widest sense, i.e., thinking of objects as animate, and treating them as if they were animate, is near-universal. Jean Piaget applied the term in child psychology in reference to an implicit understanding of the world in a child's mind which assumes that all events are the product of intention or consciousness. Piaget explains this with a cognitive inability to distinguish the external world from one's own psyche. Developmental psychology has since established that the distinction of animate vs. inanimate things is an abstraction acquired by learning.[citation needed]

The justification for attributing life to objects was stated by David Hume in his Natural History of Religion (Section III): "There is a universal tendency among mankind to conceive all beings like themselves, and to transfer to every object those qualities with which they are familiarly acquainted, and of which they are intimately conscious."[12]

Lists of phenomena, from the contemplation of which "the savage" was led to believe in animism, have been given by Sir E. B. Tylor, Herbert Spencer, Andrew Lang, and others; a controversy arose between the former as to the priority of their respective lists.[citation needed] Among these phenomena are trance states, dreams, and hallucinations.[citation needed]

Animism and religion

Animism is a belief held in many religions around the world, and is not, as some have purported, a type of religion in itself.[citation needed] It is a belief, such as shamanism, polytheism or monotheism, that is found in several religions.[citation needed] In modern usage, the term is sometimes used improperly as a catch-all classification of "other world religions" alongside major organized religions.

Origin of religion

Some theories have been put forward that the anthropocentric belief in animism among early humans was the basis for the later evolution of religions. In one such theory, put forward by Sir E. B. Tylor, early humans initially, through mere observation, recognized what might be called a soul, life-force, spirit, breath or animus within themselves; that which was present in the body in life and absent in death. These early humans equated this soul with figures which would appear in dreams and visions. These early human cultures later interpreted these spirits to be present in animals, the living plant world, and even in natural objects in a form of animism. Eventually, these early humans grew to believe that the spirits were invested and interested in human life, and performed rituals to propitiate them. These rituals and beliefs eventually evolved over time into the vast array of “developed” religions. According to Tylor, the more scientifically advanced the society, the less that society believed in Animism; however, any remnant ideologies of souls or spirits, to Tylor, represented “survivals” of the original animism of early humanity.{{link}}

World view

In many animistic world views found in hunter-gatherer cultures, the human being is often regarded as on a roughly equal footing with other animals, plants, and natural forces.[13][page needed] Therefore, it is morally imperative to treat these agents with respect. In this world view, humans are considered a part of nature, rather than superior to, or separate from it. In such societies, ritual is considered essential for survival, as it wins the favor of the spirits of one's source of food, shelter, and fertility and wards off malevolent spirits. In more elaborate animistic religions, such as Shinto, there is a greater sense of a special character to humans that sets them apart from the general run of animals and objects, while retaining the necessity of ritual to ensure good luck, favorable harvests, and so on.[citation needed]

Death

Most animistic belief systems hold that the spirit survives physical death. In some systems[which?], the spirit is believed to pass to an easier world of abundant game or ever-ripe crops, while in other systems, the spirit remains on earth as a ghost, often malignant. Still other systems combine these two beliefs, holding that the soul must journey to the spirit world without becoming lost and thus wandering as a ghost (e.g., the Navajo religion). Funeral, mourning rituals, and ancestor worship performed by those surviving the deceased are often considered necessary for the successful completion of this journey.[citation needed]

From the belief in the survival of the dead arose the practice of offering food, lighting fires, etc., at the grave, at first, maybe, as an act of friendship or filial piety, later as an act of ancestor worship. The simple offering of food or shedding of blood at the grave develops into an elaborate system of sacrifice. Even where ancestor worship is not found, the desire to provide the dead with comforts in the future life may lead to the sacrifice of wives, slaves, animals, and so on, to the breaking or burning of objects at the grave or to provide the ferryman's toll: a coin placed on each eye of the corpse to pay the traveling expenses of the soul; and, a piece of honeyed bread in the mouth to distract the three-headed dog/demon Cerberus long enough for the soul to pass it.[citation needed]

But all is not finished with the passage of the soul to the land of the dead. The soul may return to avenge its death by helping to discover the murderer, or to wreak vengeance for itself. There is a widespread belief that those who die a violent death become malignant spirits and endanger the lives of those who come near the haunted spot. In Malay folklore, the woman who dies in childbirth becomes a pontianak, a vampire-like spirit who threatens the life of human beings. People resort to magical or religious means of repelling spiritual dangers from such malignant spirits.[citation needed]

It is not surprising to find that many peoples respect and even worship animals (see totem or animal worship), often regarding them as relatives. It is clear that widespread respect was paid to animals as the abode of dead ancestors, and much of the cults to dangerous animals is traceable to this principle; though there is no need to attribute an animistic origin to it.[14]

The practice of head shrinking among Jivaroan and Urarina peoples derives from an animistic belief that if the spirits of one's mortal enemies (i.e., the nemesis of one's being) are not trapped within the head, they can escape slain bodies. After the spirit transmigrates to another body, they can take the form of a predatory animal and even exact revenge.

Mythology

A large part of mythology is based upon a belief in souls and spirits — that is, upon animism in its more general sense. Urarina myths that portray plants, inanimate objects, and non-human animals as personal beings are examples of animism in its more restrictive sense.[15]

However, many mythologies focus largely on corporeal beings rather than "spiritual" ones; the latter may even be entirely absent. Stories of transformation, deluge and doom myths, and myths of the origin of death do not necessarily have any animistic basis.[citation needed]

As mythology began to include more numerous and complex ideas about a future life and purely spiritual beings, the overlap between mythology and animism widened. However, a rich mythology does not necessarily depend on a belief in many spiritual beings.[citation needed]

Distinction from Pantheism

Animism is not the same as Pantheism, although the two are sometimes confused. Some faiths and religions are even both pantheistic and animistic. One of the main differences is that while animists believe everything to be spiritual in nature, they do not necessarily see the spiritual nature of everything in existence as being united (monism), the way pantheists do. As a result, animism puts more emphasis on the uniqueness of each individual soul. In Pantheism, everything shares the same spiritual essence, rather than having distinct spirits and/or souls.[16][17]

Science and animism

Some early scientists such as Georg Ernst Stahl (1659-1734) and Francisque Bouillier (1813–1899) had supported a form of animism which life and mind, the directive principle in evolution and growth, holding that all cannot be traced back to chemical and mechanical processes, but that there is a directive force which guides energy without altering its amount. An entirely different class of ideas, also termed animistic, is the belief in the world soul anima mundi, held by philosophers such as Schelling and others.[18][19] In the early 20th century William McDougall defended a form of animism in his book Body and Mind: A History and Defence of Animism (1911).

The physicist Nick Herbert has argued for "quantum animism" in which mind permeates the world at every level.[20] Werner Krieglstein wrote regarding his quantum animism:

Herbert's quantum animism differs from traditional animism in that it avoids assuming a dualistic model of mind and matter. Traditional dualism assumes that some kind of spirit inhabitats a body and makes it move, a ghost in the machine. Herbert's quantum animism presents the idea that every natural system has an inner life, a conscious center, from which it directs and observes its action.[21]

The terms animism and panpsychism have become related in recent years. The biologist Rupert Sheldrake has supported a form of animism which David Skrbina calls "a unique form of pansychism". Sheldrake in his book The Rebirth of Nature: New Science and the Revival of Animism (1991) has claimed that Morphic fields "animate organisms at all levels of complexity, from galaxies to giraffes, and from ants to atoms".[22] In his book The Science Delusion (2012) he wrote that the philosophy of the organism (organicism) has updated the ideas of animism as it treats all of nature as alive.[23]

Contemporary animist traditions

- Shinto, the traditional religion of Japan, is highly animistic. In Shinto, spirits of nature, or kami, are believed to exist everywhere, from the major (such as the goddess of the sun), which can be considered polytheistic, to the minor, which are more likely to be seen as a form of animism.

- Many traditional beliefs in the Philippines centuries ago, and perhaps still practiced by some to an extent or in seclusion today, are beliefs strongly associated with animism and spiritual beliefs, which have featured rituals aimed at pacifying malevolent spirits.

- There are some Hindu groups which may be considered animist. The coastal Karnataka has a different tradition of praying to spirits (see also Folk Hinduism).

- Many traditional Native American religions are fundamentally animistic. See, for example, the Lakota Sioux prayer Mitakuye Oyasin. The Haudenausaunee Thanksgiving Address, which can take an hour to recite, directs thanks towards every being - plant, animal and other.

- The New Age movement commonly purports animism in the form of the existence of nature spirits.[24]

- Modern Neopagans, especially Eco-Pagans, sometimes like to describe themselves as animists, meaning that they respect the diverse community of living beings and spirits with whom humans share the world/cosmos.[25]

- New tribalist American author Daniel Quinn identifies himself as an animist and defines animism not as a religious belief but a religion itself,[26] though with no holy scripture, organized institutions, or established dogma.[27] He considers animism the first worldwide religion, common among all tribal societies before the advent of the Agriculture Revolution and its resulting globalized culture, along with the proliferation of this culture's organized, "salvationist" religions.[28] His first discussions of animism appear in his two 1994 books: his novel, The Story of B, and his autobiography, Providence: The Story of a Fifty-Year Vision Quest.

See also

- General

- Related

References

Notes

- ^ a b Segal, p. 14.

- ^ "Animism", The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, p. 72.

- ^ Iannone, A. Pablo (2001). "animism". Dictionary of world philosophy. Taylor & Francis. p. 54. ISBN 9780415179959.

- ^ "The concept that humans possess souls and that souls have life apart from human bodies before and after death are central to animism, along with the ideas that animals, plants, and celestial bodies have spirits" (Wenner).

- ^ a b Bird-David, 1999: p. 67.

- ^ Ingold, Tim. (2000). "Totemism, Animism and the Depiction of Animals" in The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge, pp. 112-113.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. (2001). http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=animism

- ^ Tylor, E.B. Primitive Culture. London: John Murray, 1871. p. 21.

- ^ Tylor, E.B. Primitive Culture. London: John Murray, 1871. p. 260.

- ^ Bird-David, 1999: pp. 67-68

- ^ Bird-David, 1999: [page needed]

- ^ The Natural History of Religion. D. Hume. p. xix.

- ^ Fernandez-Armesto, p. 138.

- ^ "Animism", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Dean, Bartholomew 2009 Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia, Gainesville: University Press of Florida ISBN 978-081303378 [1].

- ^ Paul A. Harrison Elements of Pantheism 2004, p. 11

- ^ Carl McColman When Someone You Love Is Wiccan: A Guide to Witchcraft and Paganism for Concerned Friends, Nervous parents and Curious Co-Workers 2002, p. 97

- ^ Émile Durkheim, Neil Gross, Robert Alun Jones Durkheim's Philosophy Lectures 2004, p. 286

- ^ Animism, Vitalism, And The Medical University Of Montpellier

- ^ Graham Harvey Animism: respecting the living world 2005, p. 190

- ^ Werner J. Krieglstein Compassion: a new philosophy of the other 2002, p. 118

- ^ David Skrbina Panpsychism in the West 2005, p. 200

- ^ Rupert Sheldrake The Science Delusion Coronet Books, 2012 ISBN 1444727923

- ^ Wouter J. Hanegraaff New Age religion and Western culture 1998, p. 199

- ^ Murphy Pizza, James R. Lewis Handbook of Contemporary Paganism, 2008, pp. 408-409

- ^ Ishmael.org: Q and A #75. (1997). http://www.ishmael.org/Interaction/QandA/Detail.CFM?Record=75%7C

- ^ Ishmael.org: Q and A #400. http://www.ishmael.org/Interaction/QandA/Detail.CFM?Record=400

- ^ Quinn, Daniel. The Story of B. New York: Bantam Books. 1997

Bibliography

- Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America. Penguin, 2006.

- "Animism". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 6th ed. 2001-07. Bartleby.com. Bartleby.com Inc. (10 July 2008).

- Armstrong, Karen. A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Ballantine Books, 1994.

- Bird-David, Nurit. 1991. "Animism Revisited: Personhood, environment, and relational epistemology", Current Anthropology 40, pp. 67–91. Reprinted in Graham Harvey (ed.) 2002. Readings in Indigenous Religions (London and New York: Continuum) pp. 72–105.

- Cunningham, Scott. Living Wicca: A Further Guide for the Solitary Practitioner. Llewellyn, 2002. -- [unreliable source?]

- Dean, Bartholomew 2009 Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia, Gainesville: University Press of Florida ISBN 978-0813033785, [2].

- Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe. Ideas that Changed the World. Dorling Kindersley, 2003.

- Higginbotham, Joyce (2002). Paganism: An Introduction to Earth- Centered Religions'. Llewellyn.[unreliable source?]

- Segal, Robert (2004). Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Wenner, Sara. "Basic Beliefs of Animism". Emuseum. 2001. Minnesota State University, (10 July 2008).

Further reading

- Hallowell, A. Irving. "Ojibwa ontology, behavior, and world view" in Stanley Diamond (ed.) 1960. Culture in History (New York: Columbia University Press). Reprinted in Graham Harvey (ed.) 2002. Readings in Indigenous Religions (London and New York: Continuum) pp. 17–49.

- Harvey, Graham. 2005. Animism: Respecting the Living World (London: Hurst and co.; New York: Columbia University Press; Adelaide: Wakefield Press).

- Ingold, Tim: 'Rethinking the animate, re-animating thought'. Ethnos, 71(1) / 2006: pp. 9–20.

- Wundt, W. (1906). Mythus und Religion, Teil II. Leipzig 1906 (Völkerpsychologie, volume II).

- Quinn, Daniel. The Story of B

- Käser, Lothar: Animismus. Eine Einführung in die begrifflichen Grundlagen des Welt- und Menschenbildes traditionaler (ethnischer) Gesellschaften für Entwicklungshelfer und kirchliche Mitarbeiter in Übersee. Liebenzeller Mission, Bad Liebenzell 2004, ISBN 3-921113-61-X.

- mit dem verkürzten Untertitel Einführung in seine begrifflichen Grundlagen auch bei: Erlanger Verlag für Mission und Okumene, Neuendettelsau 2004, ISBN 3-87214-609-2.

- Badenberg, Robert: "How about 'Animism'? An Inquiry beyond Label and Legacy". In: Mission als Kommunikation. Festschrift für Ursula Wiesemann zu ihrem 75.Geburtstag, edited by Klaus W. Müller. VTR, Nürnberg 2007; ISBN 978-3-937965-75-8 and VKW, Bonn 2007; ISBN 978-3-938116-33-3.

External links

- Animism, Rinri, Modernization; the Base of Japanese Robotics

- Urban Legends Reference Pages: Weight of the Soul[3]

- Return to the Land of Souls. A documentary about animism in Ivory Coast by Jordi Esteva

- Animist Network