Sexual intercourse: Difference between revisions

m →Consent and sexual offenses: goatbuggery clarify |

|||

| Line 118: | Line 118: | ||

While sexual intercourse is the natural mode of reproduction for the human species, humans have intricate moral and ethical guidelines which regulate the practice of sexual intercourse and that vary according to [[religion and sexuality|religious]] and governmental laws. Some governments and religions also have strict designations of "appropriate" and "inappropriate" sexual behavior, which include restrictions on the types of sex acts which are permissible. A historically prohibited or regulated sex act is anal sex.<ref>William N. Eskridge Jr. Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861–2003. (2008) Viking Adult. ISBN 0-670-01862-7</ref><ref>Noelle N. R. Quenivet. Sexual Offenses in Armed Conflict & International Law. (2005) Hotei Publishing. ISBN 1-57105-341-7</ref> |

While sexual intercourse is the natural mode of reproduction for the human species, humans have intricate moral and ethical guidelines which regulate the practice of sexual intercourse and that vary according to [[religion and sexuality|religious]] and governmental laws. Some governments and religions also have strict designations of "appropriate" and "inappropriate" sexual behavior, which include restrictions on the types of sex acts which are permissible. A historically prohibited or regulated sex act is anal sex.<ref>William N. Eskridge Jr. Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861–2003. (2008) Viking Adult. ISBN 0-670-01862-7</ref><ref>Noelle N. R. Quenivet. Sexual Offenses in Armed Conflict & International Law. (2005) Hotei Publishing. ISBN 1-57105-341-7</ref> |

||

===Consent |

===Consent, sexual offenses, human-animal bonding=== |

||

Sexual intercourse with a person against their will, or without their [[informed consent|informed legal consent]], is referred to as [[rape]], and is considered a serious [[criminal law|crime]] in most countries.<ref>Marshall Cavendish Corporation Staff. Sex and Society. (2009) Cavendish, Marshall Corporation. p143-144. ISBN 0-7614-7906-6 [http://books.google.com/books?id=aVDZchwkIMEC&lpg=PA143&dq=sexual%20intercourse%20consent%202009&pg=PA143#v=onepage&q&f=false]</ref> More than 90% of rape victims are female, 99% of rapists male, and only about 5% of rapists are strangers to the victims.<ref>Jerrold S. Greenberg, Clint E. Bruess, Sarah C. Conklin. (2010). Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. p 515. ISBN 0-7637-7660-2 [http://books.google.com/books?id=1NC5R0RozBYC&lpg=PA515&dq=sexual%20intercourse%20consent%202009&pg=PA515#v=onepage&q=sexual%20intercourse%20consent%202009&f=false].</ref> |

Sexual intercourse with a person against their will, or without their [[informed consent|informed legal consent]], is referred to as [[rape]], and is considered a serious [[criminal law|crime]] in most countries.<ref>Marshall Cavendish Corporation Staff. Sex and Society. (2009) Cavendish, Marshall Corporation. p143-144. ISBN 0-7614-7906-6 [http://books.google.com/books?id=aVDZchwkIMEC&lpg=PA143&dq=sexual%20intercourse%20consent%202009&pg=PA143#v=onepage&q&f=false]</ref> More than 90% of rape victims are female, 99% of rapists male, and only about 5% of rapists are strangers to the victims.<ref>Jerrold S. Greenberg, Clint E. Bruess, Sarah C. Conklin. (2010). Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. p 515. ISBN 0-7637-7660-2 [http://books.google.com/books?id=1NC5R0RozBYC&lpg=PA515&dq=sexual%20intercourse%20consent%202009&pg=PA515#v=onepage&q=sexual%20intercourse%20consent%202009&f=false].</ref> |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

;Interspecies |

;Interspecies |

||

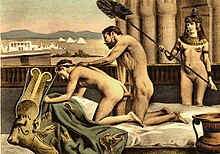

[[File:Édouard-Henri Avril (28).jpg|thumb|240px|Depiction of a goat in coition with its human partner]] |

[[File:Édouard-Henri Avril (28).jpg|thumb|240px|Depiction of a goat in coition with its human partner]][[Zoophilia]] (beastiality) is the practice of sexual activity between humans and non-human animals, or a preference for or fixation on such practice. People who practice zoophilia are known as zoophiles,<ref name=EB>"Zoophilia," ''Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2009; Retrieved 24 January 2009.</ref> zoosexuals, or simply "zoos".<ref name="Handbookth">{{Cite journal | url = http://books.google.com/?id=G_MwT9OHj4AC&pg=PA201&dq=zoophilia#v=onepage&q=zoophilia&f=false | title = The International Handbook of Animal Abuse and Cruelty: Theory, Research, and Application | isbn = 978-1-55753-565-8 | author1 = Ascione | first1 = Frank | date = 28 February 2010}}</ref> Zoophilia may also be known as zoosexuality.<ref name="Handbookth">{{Cite journal | url = http://books.google.com/?id=G_MwT9OHj4AC&pg=PA201&dq=zoophilia#v=onepage&q=zoophilia&f=false | title = The International Handbook of Animal Abuse and Cruelty: Theory, Research, and Application | isbn = 978-1-55753-565-8 | author1 = Ascione | first1 = Frank | date = 28 February 2010}}</ref> |

||

Zoophilia is a [[paraphilia]].<ref name=DSM>{{cite book |author= |title= [[Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders]]: DSM-IV | publisher = [[American Psychiatric Association]] | location=Washington, DC |year=2000 |pages= |isbn=0-89042-025-4 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref><ref name = Milner2008>{{cite book | editor = Laws DR & O'Donohue WT | last = Milner | first = JS | coauthors = Dopke CA | title = Sexual Deviance, Second Edition: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment | publisher = [[The Guilford Press]] | location = New York | year = 2008 | pages = [http://books.google.ca/books?id=yIXG9FuqbaIC&pg=PA385 384–418] |isbn=1-59385-605-9 |oclc= |doi=| chapter = Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified: Psychopathology and theory}}</ref><ref name = Lovemaps>{{cite book |author=Money, John |title=Lovemaps: Clinical Concepts of Sexual/Erotic Health and Pathology, Paraphilia, and Gender Transposition in Childhood, Adolescence, and Maturity |publisher=[[Prometheus Books]] |location=Buffalo, N.Y |year=1988 |pages= |isbn=0-87975-456-7 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref><ref name = Seto2000>{{cite book |editor = Hersen M; Van Hasselt VB | title = Aggression and violence: an introductory text |publisher= [[Allyn & Bacon]] |location=Boston |year=2000 |pages= 198–213 |isbn=0-205-26721-1 |oclc= |doi=| last = Seto| first = MC| coauthors = Barbaree HE | chapter = Paraphilias}}</ref> Sex with animals is not outlawed in some jurisdictions, but, in most countries, it is illegal under [[cruelty to animals|animal abuse]] laws or laws dealing with [[crime against nature|crimes against nature]]. A Danish Animal Ethics Council report in 2006 concluded that ethically performed zoosexual activity is capable of providing a positive experience for all participants, and that some non-human animals are [[Anthropophilia in animals|sexually attracted to humans]]<ref>[http://www.justitsministeriet.dk/fileadmin/downloads/Dyrevaernsraad/Seksuel%20omgang%20med%20dyr.pdf Danish Animal Ethics Council report] ''Udtalelse om menneskers seksuelle omgang med dyr'' published November 2006. Council members included two academics, two farmers/smallholders, and two veterinary surgeons, as well as a third veterinary surgeon acting as secretary.</ref> (for example, [[dolphins]]).<ref>{{cite news| url=http://articles.cnn.com/2002-06-04/world/uk.dolphin_1_ric-o-barry-dolphin-swimmers?_s=PM:WORLD | work=CNN | title=Bid to save over-friendly dolphin | date=28 May 2002}}</ref> |

Zoophilia is a [[paraphilia]].<ref name=DSM>{{cite book |author= |title= [[Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders]]: DSM-IV | publisher = [[American Psychiatric Association]] | location=Washington, DC |year=2000 |pages= |isbn=0-89042-025-4 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref><ref name = Milner2008>{{cite book | editor = Laws DR & O'Donohue WT | last = Milner | first = JS | coauthors = Dopke CA | title = Sexual Deviance, Second Edition: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment | publisher = [[The Guilford Press]] | location = New York | year = 2008 | pages = [http://books.google.ca/books?id=yIXG9FuqbaIC&pg=PA385 384–418] |isbn=1-59385-605-9 |oclc= |doi=| chapter = Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified: Psychopathology and theory}}</ref><ref name = Lovemaps>{{cite book |author=Money, John |title=Lovemaps: Clinical Concepts of Sexual/Erotic Health and Pathology, Paraphilia, and Gender Transposition in Childhood, Adolescence, and Maturity |publisher=[[Prometheus Books]] |location=Buffalo, N.Y |year=1988 |pages= |isbn=0-87975-456-7 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref><ref name = Seto2000>{{cite book |editor = Hersen M; Van Hasselt VB | title = Aggression and violence: an introductory text |publisher= [[Allyn & Bacon]] |location=Boston |year=2000 |pages= 198–213 |isbn=0-205-26721-1 |oclc= |doi=| last = Seto| first = MC| coauthors = Barbaree HE | chapter = Paraphilias}}</ref> Sex with animals is not outlawed in some jurisdictions, but, in most countries, it is illegal under [[cruelty to animals|animal abuse]] laws or laws dealing with [[crime against nature|crimes against nature]]. The offence of [[buggery]] has been found to include buggery with an animal in Britain.<ref>R v Gaston 73 Cr App R 164, [[Court of Appeal|CA]]</ref> A Danish Animal Ethics Council report in 2006 concluded that ethically performed zoosexual activity is capable of providing a positive experience for all participants, and that some non-human animals are [[Anthropophilia in animals|sexually attracted to humans]]<ref>[http://www.justitsministeriet.dk/fileadmin/downloads/Dyrevaernsraad/Seksuel%20omgang%20med%20dyr.pdf Danish Animal Ethics Council report] ''Udtalelse om menneskers seksuelle omgang med dyr'' published November 2006. Council members included two academics, two farmers/smallholders, and two veterinary surgeons, as well as a third veterinary surgeon acting as secretary.</ref> (for example, [[dolphins]]).<ref>{{cite news| url=http://articles.cnn.com/2002-06-04/world/uk.dolphin_1_ric-o-barry-dolphin-swimmers?_s=PM:WORLD | work=CNN | title=Bid to save over-friendly dolphin | date=28 May 2002}}</ref> |

||

;Penetration |

;Penetration |

||

Revision as of 02:33, 8 September 2012

Sexual intercourse, also known as copulation or coitus, is commonly defined as the insertion of a male's penis into a female's vagina for the purposes of sexual pleasure or reproduction.[3][4][5][6] The term may also describe other sexual penetrative acts, such as anal sex, oral sex and fingering, or use of a strap-on dildo, which can be practiced by same-or-interspecies heterosexual and homosexual pairings or multiple partners.[3][6][7][8]

Sexual intercourse can play a strong role in human bonding, often being used solely for pleasure and leading to stronger emotional bonds,[9] and there are a variety of views concerning what constitutes sexual intercourse or other sexual activity.[10] For example, non-penetrative sex (such as non-penetrative cunnilingus) has been referred to as "outercourse",[11][12][13] but may also be among the sexual acts contributing to human bonding and considered intercourse. The term sex, often a shorthand for sexual intercourse, can be taken to mean any form of sexual activity (i.e. all forms of intercourse and outercourse).[6][10][14][15] Because individuals can be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases during these activities,[16][17] although the transmission risk is significantly reduced during non-penetrative sex,[12][18] safe sex practices are advised.[16]

In human societies, some jurisdictions have placed various restrictive laws against certain sexual activities, such as sex with minors, incest, extramarital sex, position-of-trust sex, prostitution, sodomy, public lewdness, rape, and beastiality. Religious beliefs can play a role in decisions about sex, or its purpose, as well; for example, beliefs about what sexual acts constitute virginity loss or the decision to make a virginity pledge.[19][20][21] Some sections of Christianity commonly view sex between a married couple for the purpose of reproduction as holy, while other sections may not.[22] Modern Judaism and Islam view sexual intercourse between husband and wife as a spiritual and edifying action. Hinduism and Buddhism views on sexuality have differing interpretations.

Sexual intercourse between non-human animals is more often referred to as copulation; for most, mating and copulation occurs at the point of estrus (the most fertile period of time in the female's reproductive cycle),[23][24] which increases the chances of successful impregnation. However, bonobos,[25] dolphins,[26] and chimpanzees are known to engage in sexual intercourse even when the female is not in estrus, and to engage in sex acts with same-sex partners.[26][27] Like humans engaging in sex primarily for pleasure,[9] this behavior in the above mentioned animals is also presumed to be for pleasure,[28] and a contributing factor to strengthening their social bonds.[9]

Practices

Etymology, definitions, and stimulation factors

Sexual intercourse is also known as copulation, coitus or coition; coitus is derived from the Latin word coitio or coire, meaning "a coming together or joining together" or "to go together" and is usually defined as penile-vaginal penetration.[3][29][30][31] Copulation, although usually used to describe the mating process of non-human animals, is defined as "the transfer of the sperm from male to female" or "the act of sexual procreation between a man and a woman".[32][33] As such, common vernacular and research often limit sexual intercourse to penile-vaginal penetration, with virginity loss being predicated on the activity,[10][19][20][34] while the term sex and phrase "having sex" commonly mean any sexual activity – penetrative and non-penetrative (intercourse and outercourse).[10][14][35] The World Health Organization states that non-English languages and cultures use different terms for sexual activity, with slightly different meanings.[14]

Sexual intercourse may be preceded by foreplay, which leads to sexual arousal of the partners, resulting in the erection of the penis or (usually) natural lubrication of the vagina. Anal and oral sex may be regarded as sexual intercourse,[3][6][10] but they, along with non-penetrative sex acts, may also be regarded as maintaining "technical virginity" or as outercourse, regardless of any penetrative aspects.[20][36] Heterosexual couples often engage in these practices not only for sexual pleasure, but as a way of avoiding pregnancy and maintaining that they are virgins because they have not yet engaged in penile-vaginal sex.[20][37][38][39] Likewise, some gay men view frotting or oral sex as maintaining their virginity, with anal penetration regarded as virginity loss, while other gay men consider frotting or oral sex to be their main forms of intercourse.[40][41][42][43] Lesbians may regard oral sex or fingering as loss of virginity.[44][45]

In 1999, a study by the Kinsey Institute, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, examined the definition of sex based on a 1991 random sample of 599 college students from 29 U.S. states; it reported that 60% said oral-genital contact (fellatio, cunnilingus) did not constitute having sex.[35][46] Similarly, a 2003 study published in The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, which surveyed university students from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia with regard to the students' definitions of having sex, reported that "[w]hile the vast majority of respondents (more than 97%) in these three studies included penile-vaginal intercourse in their definition of sex, fewer (between 70% and 90%) respondents considered penile-anal intercourse to constitute having sex" and that "oral-genital behaviours were defined as sex by between 32% and 58% of respondents".[10] A different study by the Kinsey Institute sampled 484 people, ranging in ages 18–96. "Nearly 95 percent of people in the study agreed that penile-vaginal intercourse meant 'had sex.' But the numbers changed as the questions got more specific." 11 percent of respondents based "had sex" on whether the man had achieved an orgasm, concluding that absence of an orgasm does not constitute "having had" sex. "About 80 percent of respondents said penile-anal intercourse meant 'had sex.' About 70 percent of people believed oral sex was sex."[35]

What defines sexual activity during penetrative or non-penetrative sex is varied,[10][14][35] and may encompass a number of sex positions.[2][29] During coitus, both of the partners move their hips to move the penis backward and forward inside the vagina to cause friction, typically without fully removing the penis. In this way, they stimulate themselves and each other, often continuing until orgasm in either or both partners is achieved.[29] For human females, stimulation of the clitoris plays a significant role in sexual intercourse; 70–80% require direct clitoral stimulation to achieve orgasm,[47][48][49][50] though indirect clitoral stimulation (for example, via vaginal intercourse) may also be sufficient (see orgasm in females).[51][52] As such, some couples may engage in the woman on top position or the coital alignment technique, a technique combining the "riding high" variation of the missionary position with pressure-counterpressure movements performed by each partner in rhythm with sexual penetration, to maximize clitoral stimulation.[1][3][53][54]

Anal sex involves stimulation of the anus, anal cavity, sphincter valve and/or rectum, mostly commonly employing the insertion of a man's penis into another person's rectum.[55][56] Oral sex consists of all the sexual activities that involve the use of the mouth, tongue, and throat to stimulate genitalia. It is sometimes performed to the exclusion of all other forms of sexual activity, and may include the ingestion or absorption of semen or vaginal fluids.[11][57] Fingering is the manual (genital) manipulation of the clitoris, vulva, vagina, or anus for the purpose of sexual arousal and sexual stimulation. It may constitute the entire sexual encounter or it may be part of mutual masturbation, foreplay or other sexual activities.[57][58]

Bonding and affection

In animals, copulation ranges from a purely reproductive activity to one of emotional bonding between mated pairs. Sexual intercourse and other sexual activity typically plays a powerful role in human bonding. For example, in many societies, it is normal for couples to have frequent intercourse while using some method of birth control (contraception), sharing pleasure and strengthening their emotional bond through sexual activity even though they are deliberately avoiding pregnancy.[9]

In humans and bonobos, the female undergoes relatively concealed ovulation so that both male and female partners commonly do not know whether she is fertile at any given moment. One possible reason for this distinct biological feature may be formation of strong emotional bonds between sexual partners important for social interactions and, in the case of humans, long-term partnership rather than immediate sexual reproduction.[9]

Humans, bonobos, dolphins, and chimpanzees are all intelligent social animals, whose cooperative behavior proves significantly more successful than that of any individual alone. In these animals, the use of sex has evolved beyond reproduction, to apparently serve additional social functions.[25][26][27] Sex reinforces intimate social bonds between individuals to form larger social structures. The resulting cooperation encourages collective tasks that promote the survival of each member of the group.[9]

Reproduction, reproductive methods and pregnancy

Penetration by the hardened, erect penis is additionally known as intromission, or by the Latin name immissio penis (Latin for "insertion of the penis"). During ejaculation, which usually accompanies male orgasm, a series of muscular contractions delivers semen containing male gametes known as sperm cells or spermatozoa from the penis into the vagina. The subsequent route of the sperm from the vault of the vagina is through the cervix and into the uterus, and then into the fallopian tubes. Millions of sperm are present in each ejaculation, to increase the chances of one fertilizing an egg or ovum (see sperm competition). When a fertile ovum from the female is present in the fallopian tubes, the male gamete joins with the ovum, resulting in fertilization and the formation of a new embryo. When a fertilized ovum reaches the uterus, it becomes implanted in the lining of the uterus – known as the endometrium – and a pregnancy begins. Unlike most species, human sexual activity is not linked to periods of estrus and can take place at any time during the reproductive cycle, even during pregnancy.[59] Where a sperm donor has sexual intercourse with a woman who is not his partner, for the sole purpose of impregnating the woman, this may be known as natural insemination, as opposed to artificial insemination. However, most sperm donors donate their sperm through a sperm bank and pregnancy is achieved through artificial insemination.[60]

In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 123 million women become pregnant world-wide each year, and around 87 million of those pregnancies or 70.7% are unintentional. About 46 million pregnancies per year reportedly end in induced abortion.[61] About 6 million U.S. women become pregnant per year. Out of known pregnancies, two-thirds result in live births and roughly 25% in abortions; the remainder end in miscarriage. However, many more women become pregnant and miscarry without even realizing it, instead mistaking the miscarriage for an unusually heavy menstruation.[62] The U.S. teenage pregnancy rate fell by 27 percent between 1990 and 2000, from 116.3 pregnancies per 1,000 girls aged 15–19 to 84.5. This data includes live births, abortions, and fetal losses. Almost 1 million American teenage women, 10% of all women aged 15–19 and 19% of those who report having had intercourse, become pregnant each year.[63] Britain has been stated to have a teenage pregnancy rate similar to America's.[64]

Reproductive methods and pregnancy also extend to gay and lesbian couples. For gay male pairings, there is the option of surrogate pregnancy; for lesbian couples, there is donor insemination in addition to choosing surrogate pregnancy.[65][66] Further, developmental biologists have been researching and developing techniques to facilitate biological same-sex reproduction, though this has yet to be demonstrated in humans (see same-sex reproduction).[67][68] Surrogacy and donor insemination remain the primary methods. Surrogacy is an arrangement in which a woman carries and delivers a child for another couple or person. The woman may be the child's genetic mother (traditional surrogacy) or she may carry a pregnancy to delivery after having another woman's eggs transferred to her uterus (gestational surrogacy). Gay and lesbian pairings who want the host to have no genetic connection to the child may choose gestational surrogacy and enter into a contract with an egg donor. Gay male couples might decide that they should both contribute semen for the in vitro fertilisation (IVF) process, which further establishes the couple's joint intention to become parents.[66] Lesbian couples often have contracts drafted to extinguish the legal rights of the sperm donor, while creating legal rights for the parent who is not biologically related to the child.[69]

Prevalence, safe sex, and contraception

The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (November 2011) |

According to a national survey conducted in the U.S. in 1995, at least 3/4 of all men and women in the U.S. have had intercourse by their late teenage years, and more than 2/3 of all sexually experienced teens have had 2 or more partners.[70] Among sexually active 15- to 19-year-olds in the U.S., 83% of females and 91% of males reported using at least one method of birth control during last intercourse.[71]

There are a variety of safe sex practices, including non-penetrative sex acts,[12][18] and heterosexual couples may use oral or anal sex (or both) as a means of contraception.[37][39] In 2004, the Guttmacher Institute indicated in 2002 that 62% of the 62 million women aged 15–44 are currently using a contraceptive method, that among U.S. women who practice contraception, the Pill is the most popular choice (30.6%), followed by tubal sterilization (27.0%) and the male condom (18.0%), and that 27% of teenage women using contraceptives choose condoms as their primary method.[72]

In 2006, a survey conducted by The Observer suggested that most adolescents in Britain were waiting longer to have sexual intercourse than they were only a few years earlier. In 2002, it was reported that 32% of British teenagers were having sex before the age of 16; in 2006, it was only 20%. The average age a teen lost his/her virginity was reportedly 17.13 years in 2002; in 2006, it was 17.44 years on average for girls and 18.06 for boys. The most notable drop among teens who reported having sex was 14- and 15-year-olds.[73] A 2008 survey conducted by YouGov for Channel 4 suggested that 40% of all 14- to 17-year-olds are sexually active, 74% of sexually active 14- to 17-year-olds have had a sexual experience under the age of consent, and 6% of teens would wait until marriage before having sex.[74] Sexually transmitted infections are also on the increase in Britain.[64] One in nine sexually active teens has chlamydia and 790,000 teens have sexually transmitted infections. In 2006, The Independent newspaper reported that the biggest rise in sexually transmitted infections was in syphilis, which rose by more than 20%, while increases were also seen in cases of genital warts and herpes.[75]

The National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) indicated in 2010 that 1 of 4 acts of vaginal intercourse are condom-protected in the U.S. (1 in 3 among singles), condom use is higher among black and Hispanic Americans than among white Americans and those from other racial groups, and adults using a condom for intercourse were just as likely to rate the sexual extent positively in terms of arousal, pleasure and orgasm than when having intercourse without one.[76]

Duration and sexual difficulties

Intercourse often ends when the man has ejaculated, and thus the partner might not have time to reach orgasm. In addition, premature ejaculation (PE) is common, and women often require a substantially longer duration of stimulation with a sexual partner than men do before reaching an orgasm.[77][78][79] Masters and Johnson found that men took about 4 minutes to reach orgasm with their partners; women took about 10–20 minutes to reach orgasm with their partners, but 4 minutes to reach orgasm when they masturbated.[79] Scholars Weiten, Dunn and Hammer have reasoned, "Unfortunately, many couples are locked into the idea that orgasms should be achieved only through intercourse [penetrative vaginal sex]. Even the word foreplay suggests that any other form of sexual stimulation is merely preparation for the 'main event.'... ...Because women reach orgasm through intercourse less consistently than men, they are more likely than men to have faked an orgasm."[79]

In 1991, scholars June M. Reinisch and Ruth Beasley of the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction stated, "The truth is that the time between penetration and ejaculation varies not only from man to man, but from one time to the next for the same man." They added that the appropriate length for intercourse is the length of time it takes for both partners to be mutually satisfied, emphasizing that Kinsey "found that 75 percent of men ejaculated within two minutes of penetration. But he didn't ask if the men or their partners considered two minutes mutually satisfying" and "more recent research reports slightly longer times for intercourse".[80] A 2008 survey of Canadian and American sex therapists stated that the average time for intromission was 7 minutes and that 1 to 2 minutes was too short, 3 to 7 minutes was adequate and 7 to 13 minutes desirable, while 10 to 30 minutes was too long.[81][82]

Anorgasmia is regular difficulty reaching orgasm after ample sexual stimulation, causing personal distress. This is much more common in women than in men.[78][83] The physical structure of the act of coitus favors penile stimulation over clitoral stimulation. The location of the clitoris then usually necessitates manual stimulation in order for the female to achieve orgasm.[79] About 15% of women report difficulties with orgasm, 10% have never climaxed, and 40–50% have either complained about sexual dissatisfaction or experienced difficulty becoming sexually aroused at some point in their lives. 75% of men and 29% of women always have orgasms with their partner.[84]

Vaginismus is the involuntary tensing of the pelvic floor musculature, making coitus distressing, painful, and sometimes impossible for women.[85][86][87] It is a conditioned reflex of the pubococcygeus muscle, sometimes referred to as the "PC muscle". Vaginismus can be a vicious cycle for women, they expect to experience pain during intercourse, which then causes a muscle spasm, which leads to painful intercourse. Treatment of vaginismus often includes both psychological and behavioral techniques, including the use of vaginal dilators. A new medical treatment using Botox is in the testing phase.[87][88] Some women also experience dyspareunia, a medical term for painful or uncomfortable intercourse, of unknown cause.[89][90]

About 40% of males suffer from some form of erectile dysfunction (ED) or impotence, at least occasionally.[91] For those whose impotence is caused by medical conditions, prescription drugs such as Viagra, Cialis, and Levitra are available. However, doctors caution against the unnecessary use of these drugs because they are accompanied by serious risks such as increased chance of heart attack. Moreover, using a drug to counteract the symptom—impotence—can mask the underlying problem causing the impotence and does not resolve it. A serious medical condition might be aggravated if left untreated.[92]

Premature ejaculation is more common than erectile dysfunction. "Estimates vary, but as many as 1 out of 3 men may be affected by [premature ejaculation] at some time."[77] "Masters and Johnson speculated that premature ejaculation is the most common sexual dysfunction, even though more men seek therapy for erectile difficulties." This is because, "although an estimated 15 percent to 20 percent of men experience difficulty controlling rapid ejaculation, most do not consider it a problem requiring help, and many women have difficulty expressing their sexual needs".[80] The American Urological Association (AUA) estimates that premature ejaculation could affect 21 percent of men in the United States.[93] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA or USFDA) is examining the drug dapoxetine to treat premature ejaculation. In clinical trials, those with PE who took dapoxetine experienced intercourse three to four times longer before orgasm than without the drug. Another ejaculation-related disorder is delayed ejaculation, which can be caused as an unwanted side effect of antidepressant medications such as Fluvoxamine.[94][95]

Although disability-related pain and mobility impairment can hamper intercourse, in many cases the most significant impediments to intercourse for individuals with a disability are psychological.[96] In particular, people who have a disability can find intercourse daunting due to issues involving their self-concept as a sexual being,[97][98] or partner's discomfort or perceived discomfort.[96] Temporary difficulties can arise with alcohol and sex as alcohol initially increases interest (through disinhibition) but decreases capacity with greater intake.[99]

Health effects

Benefits

In humans, sex has been claimed to produce health benefits as varied as improved sense of smell,[100] stress and blood pressure reduction,[101][102] increased immunity,[103] and decreased risk of prostate cancer.[104][105][106] Sexual intimacy, as well as orgasms, increases levels of the hormone oxytocin, also known as "the love hormone", which helps people bond and build trust.[107][108][109] Sex is also known as one of many mood repair strategies, which means it can be used to help dissipate feelings of sadness or depression.[110] A long-term study of 3,500 people between 30 and 101 by clinical neuropsychologist David Weeks, MD, head of old age psychology at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital in Scotland, found that "sex helps you look between four and seven years younger", according to impartial ratings of the subjects' photos. Exclusive causation, however, is unclear, and the benefits may be indirectly related to sex and directly related to significant reductions in stress, greater contentment, and better sleep that sex promotes.[111][112][113]

Risks

In contrast to its benefits, sexual intercourse can also be a disease vector.[114] There are 19 million new cases of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) every year in the U.S.,[17] and worldwide there are over 340 million STDs a year.[115] More than half of all STDs occur in adolescents and young adults aged 15–24 years.[116] At least one in four U.S. teenage girls has a sexually transmitted disease.[17][117] In the US, about 30% of 15–17 year old adolescents have had sexual intercourse, but only about 80% of 15–19 year old adolescents report using condoms for their first sexual intercourse.[118] More than 75% of young women age 18–25 years felt they were at low risk of acquiring an STD in one study.[119] Some sexually transmitted infections include:

- Chlamydia is particularly dangerous because there are many infected individuals who experience no symptoms.[120] Left untreated, chlamydia can lead to many complications, especially for women (such as the inability to bear children later in life).[121]

- Hepatitis B can also be transmitted through sexual contact.[122] The disease is most common in China and other parts of Asia where 8–10% of the adult population is infected with Hepatitis.[123] About a third of the world's population, more than 2 billion people, have been infected with the hepatitis B virus.[123]

- Syphilis infection is on the rise in all parts of the United States and is related to about 21% of fetal and newborn deaths in sub-Saharan Africa.[124][125] Syphilis causes genital sores that make it easier to transmit and contract HIV.[125]

- AIDS is caused by HIV which is spread primarily via sexual intercourse.[126] The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that in 2008, approximately 33.4 million people had HIV (nearly half of them African Americans),[127] and 2 million died of AIDS worldwide.[126]

Safe sex is a relevant harm reduction philosophy.[16][128] Condoms and dental dams are widely recommended for the prevention of STDs. According to reports by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and World Health Organization, correct and consistent use of latex condoms reduces the risk of HIV/AIDS transmission by approximately 85–99% relative to risk when unprotected.[129][130]

Slut-shaming is the consequence of guilt and complex of inferiority concomitant with the exposed tendency of sexual promiscuity including its signposts of acting or dressing in a way that is slutty or excessively sexual, for example, wearing fuck-me shoes.[132]

People, especially those who get little or no physical exercise, have a slightly increased risk of triggering heart attack or sudden cardiac death when they engage in sexual intercourse, or any other vigorous physical exercise which is engaged in on a sporadic basis. Increased risk is temporary with incidents occurring within a few hours of the activity. Regular exercise reduces but does not eliminate the increased risk.[133]

Social effects

Adults

Alex Comfort and others posit three potential advantages of intercourse in humans, which are not mutually exclusive: reproductive, relational, and recreational.[9][134] While the development of the Pill and other highly effective forms of contraception in the mid- and late 20th century increased people's ability to segregate these three functions, they still overlap a great deal and in complex patterns. For example: A fertile couple may have intercourse while contracepting not only to experience sexual pleasure (recreational), but also as a means of emotional intimacy (relational), thus deepening their bonding, making their relationship more stable and more capable of sustaining children in the future (deferred reproductive). This same couple may emphasize different aspects of intercourse on different occasions, being playful during one episode of intercourse (recreational), experiencing deep emotional connection on another occasion (relational), and later, after discontinuing contraception, seeking to achieve pregnancy (reproductive, or more likely reproductive and relational).[134]

Nearly all Americans marry during their lifetime; yet close to half of all first marriages are expected to end in separation or divorce, many within a few years,[135] and subsequent marriages are even more likely to end.[136] Sexual dissatisfaction is associated with increased risk of divorce and relationship dissolution.[136]

According to the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB), in 2010, men whose most recent sexual encounter was with a relationship partner reported greater arousal, greater pleasure, fewer problems with erectile function, orgasm, and less pain during the event than men whose last sexual encounter was with a non-relationship partner.[76] According to the Journal of Counseling & Development, many women express that their most satisfying sexual experiences entail being connected to someone, rather than solely basing satisfaction on orgasm.[137]

Adolescents

With regard to adolescent sexuality, sexual intercourse is also often for relational and recreational purposes. However, teenage pregnancy is usually disparaged, and research suggests that the earlier onset of puberty for children puts pressure on children and teenagers to act like adults before they are emotionally or cognitively ready,[138][139] and thus are at risk to suffer from emotional distress as a result of their sexual activities.[139][140][141][142][143] Some studies have concluded that engaging in sex leaves adolescents, and especially girls, with higher levels of stress and depression.[144] A majority of adolescents in the United States have been provided with some information regarding sexuality,[145] though there have been efforts among social conservatives in the United States government to limit sex education in public schools to abstinence-only sex education curricula.[146]

One group of Canadian researchers found a relationship between self-esteem and sexual activity. They found that students, especially girls, who were verbally abused by teachers or rejected by their peers were more likely than other students to engage in sex by the end of the Grade 7. The researchers speculate that low self-esteem increases the likelihood of sexual activity: "low self-esteem seemed to explain the link between peer rejection and early sex. Girls with a poor self-image may see sex as a way to become 'popular', according to the researchers".[147]

In India, there is growing evidence that adolescents are becoming more sexually active outside of marriage, which is feared to lead to an increase in the spread of HIV/AIDS among adolescents, as well as the number of unwanted pregnancies and abortions, and add to the conflict between contemporary social values. In India, adolescents have relatively poor access to health care and education, and with cultural norms opposing extramarital sexual behavior, "these implications may acquire threatening dimensions for the society and the nation".[148]

Not all views on adolescent sexual behavior are negative, however. Psychiatrist Lynn Ponton writes, "All adolescents have sex lives, whether they are sexually active with others, with themselves, or seemingly not at all," and that viewing adolescent sexuality as a potentially positive experience, rather than as something inherently dangerous, may help young people develop healthier patterns and make more positive choices regarding sex.[138] Likewise, others state that long-term romantic relationships allow adolescents to gain the skills necessary for high-quality relationships later in life[149] and develop feelings of self-worth. Overall, positive romantic relationships among adolescents can result in long-term benefits. High-quality romantic relationships are associated with higher commitment in early adulthood[150] and are positively associated with self-esteem, self-confidence, and social competence.[151][152]

Ethical, religious, and legal views

While sexual intercourse is the natural mode of reproduction for the human species, humans have intricate moral and ethical guidelines which regulate the practice of sexual intercourse and that vary according to religious and governmental laws. Some governments and religions also have strict designations of "appropriate" and "inappropriate" sexual behavior, which include restrictions on the types of sex acts which are permissible. A historically prohibited or regulated sex act is anal sex.[153][154]

Consent, sexual offenses, human-animal bonding

Sexual intercourse with a person against their will, or without their informed legal consent, is referred to as rape, and is considered a serious crime in most countries.[155] More than 90% of rape victims are female, 99% of rapists male, and only about 5% of rapists are strangers to the victims.[156]

Most developed countries have age of consent laws specifying the minimum legal age a person may engage in sexual intercourse with substantially older persons, usually set at about 16–18, while the legal age of consent ranges from 12–20 years of age or is not a matter of law in other countries.[157] Sex with a person under the age of consent, regardless of their stated consent, is often considered to be sexual assault or statutory rape depending on differences in ages of the participants.

Some countries codify rape as any sex with a person of diminished or insufficient mental capacity to give consent, regardless of age.[158]

The expression "sexual intercourse" has been used as a term of art in England and Wales and New York State. In England and Wales, from its enactment to its repeal on the 1 May 2004,[159] section 44 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 read:

Where, on the trial of any offence under this Act, it is necessary to prove sexual intercourse (whether natural or unnatural), it shall not be necessary to prove the completion of the intercourse by the emission of seed, but the intercourse shall be deemed complete upon proof of penetration only.

- Interspecies

Zoophilia (beastiality) is the practice of sexual activity between humans and non-human animals, or a preference for or fixation on such practice. People who practice zoophilia are known as zoophiles,[160] zoosexuals, or simply "zoos".[161] Zoophilia may also be known as zoosexuality.[161]

Zoophilia is a paraphilia.[162][163][164][165] Sex with animals is not outlawed in some jurisdictions, but, in most countries, it is illegal under animal abuse laws or laws dealing with crimes against nature. The offence of buggery has been found to include buggery with an animal in Britain.[166] A Danish Animal Ethics Council report in 2006 concluded that ethically performed zoosexual activity is capable of providing a positive experience for all participants, and that some non-human animals are sexually attracted to humans[167] (for example, dolphins).[168]

- Penetration

According to cases decided on the meaning of the statutory definition of carnal knowledge under the Offences against the Person Act 1828, which was in identical terms to this definition, the slightest penetration was sufficient.[169] The book "Archbold" said that it "submitted" that this continued to be the law under the new enactment.[170]

- Continuing act

See Kaitamaki v R [1985] AC 147, [1984] 3 WLR 137, [1984] 2 All ER 435, 79 Cr App R 251, [1984] Crim LR 564, PC (decided under equivalent legislation in New Zealand).

Section 7(2) of the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1976 contained the following words: "In this Act . . . references to sexual intercourse shall be construed in accordance with section 44 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 so far as it relates to natural intercourse (under which such intercourse is deemed complete on proof of penetration only)". The Act made provision, in relation to rape and related offences, for England and Wales, and for courts-martial elsewhere.

From 3 November 1994 to 1 May 2004, section 1(2)(a) of the Sexual Offences Act 1956 (as substituted by section 142 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994) referred to "sexual intercourse with a person (whether vaginal or anal)". This section created the offence of rape in England and Wales.

The penal code in New York State provides: § 130.00 Sex offenses; definitions of terms: 1. "Sexual intercourse" has its ordinary meaning and occurs upon any penetration, however slight.[171]

Romantic relationships

Sexual orientation and gender

There is considerable legal variability regarding definitions of and the legality of sexual intercourse between persons of the same sex or gender. For example, in 2003 the New Hampshire Supreme Court ruled that female same-sex relations did not constitute sexual intercourse, based on a 1961 definition from Webster's Third New International Dictionary, in Blanchflower v. Blanchflower, and thereby an accused wife in a divorce case was found not guilty of adultery based on this technicality. Some countries, such as Islamic countries, consider homosexual behavior to be an offense punishable by imprisonment or execution.[172]

Marriage and relationships

Sexual intercourse has traditionally been considered an essential part of a marriage; many religious customs required consummation of the marriage by sexual intercourse, and the failure for any reason to consummate the marriage was a ground for annulment, which did not require a divorce process. Annulment declaration implied that the marriage was void from the start – i.e. there was in law no marriage. Furthermore, continuing sexual relations between the marriage partners is commonly considered a 'marital right' by many religions, permissible to married couples, generally for the purpose of reproduction. Today, there is wide variation in the opinions and teachings about sexual intercourse relative to marriage and other intimate relationships by the world's religions. Examples:

- Scientology counsels against premarital sex only for its Sea Org religious order. Sex in scientology is a vital part of the Second Dynamic. The illness and perversion of homosexuality is deplored for its depravity.

- Most denominations of Christianity, including Catholicism,[22] have strict views or rules on what sexual practices are acceptable or, more specifically, what are not.[173] Most Christian views on sex are formed or influenced by various interpretations of the Bible.[174] Sex outside of marriage is considered a sin in some churches, and sex may be referred to as a "sacred covenant" between husband and wife. Historically, Christian teachings often promoted celibacy,[175] although today usually only certain members (for example certain religious leaders) of some groups take a vow of celibacy, forsaking both marriage and any type of sexual or romantic activity. Some Christians view sex, particularly sexual intercourse between a married couple, as "holy" or a "holy sacrament".[22][175] Some Christians interpret the Bible to forbid the "misuse of sexual organs" and take that to mean that only penile/vaginal penetrative intercourse is acceptable, while some argue that the Bible is not clear on oral sex and that it is a personal decision as to whether its acceptable within marriage.[176]

- In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or Mormonism, sexual relations within the bonds of matrimony are seen as beautiful and sacred. Mormons consider sexual relations to be ordained of God for the creation of children and for the expression of love between husband and wife. Members are encouraged to not have any sexual relations before marriage, and be completely faithful to their spouse after marriage.[177]

- In Judaism, a married Jewish man is required to provide his wife with sexual pleasure called onah (literally, "her time"), which is one of the conditions he takes upon himself as part of the Jewish marriage contract, ketubah, that he gives her during the Jewish wedding ceremony. In Jewish views on marriage, sexual desire is not evil, but must be satisfied in the proper time, place and manner.[178]

- Islam views sex within marriage as something pleasurable, a spiritual activity, and a duty.[179][180][181] In Shi'ia Islam, men are allowed to enter into an unlimited number of temporary marriages, which are contracted to last for a period of minutes to multiple years and permit sexual intercourse. Shi'ia women are allowed to enter only one marriage at a time, whether temporary or permanent.

- Wiccans believe that, as declared within the Charge of the Goddess, to "Let my [the Goddess] worship be within the heart that rejoiceth; for behold, all acts of love and pleasure are my rituals." This statement appears to allow one freedom to explore sensuality and pleasure, and mixed with the final maxim within the Wiccan Rede – "26. Eight words the Wiccan Rede fulfill – an’ it harm none, do what ye will."[182] – Wiccans are encouraged to be responsible with their sexual encounters, in whatever variety they may occur.[183]

- Hinduism has varied views about sexuality, but Hindu society, in general, perceives extramarital sex to be immoral and shameful.[179]

- Buddhist ethics, in its most common formulation, holds that one should neither be attached to nor crave sensual pleasure.

- In the Bahá'í Faith, sexual relationships are permitted only between a husband and wife.[184]

- Unitarian Universalists, with an emphasis on strong interpersonal ethics, do not place boundaries on the occurrence of sexual intercourse among consenting adults.[185]

- According to the Brahma Kumaris and Prajapita Brahma Kumaris religion, the power of lust is the root of all evil and worse than murder.[186] Purity (celibacy) is promoted for peace and to prepare for life in forthcoming Heaven on earth for 2,500 years when children will be created by the power of the mind.[187][188]

- Shakers believe that sexual intercourse is the root of all sin and that all people should therefore be celibate, including married couples. Predictably, the original Shaker community that peaked at 6,000 full members in 1840 dwindled to three members by 2009.[189]

In some cases, the sexual intercourse between two people is seen as counter to religious law or doctrine. In many religious communities, including the Catholic Church and Mahayana Buddhists, religious leaders are expected to refrain from sexual intercourse in order to devote their full attention, energy, and loyalty to their religious duties.[190]

Opposition to same-sex marriage is largely based on the belief that sexual intercourse and sexual orientation should be of a heterosexual nature.[191][192][193][194] The recognition of such marriages is a civil rights, political, social, moral, and religious issue in many nations, and the conflicts arise over whether same-sex couples should be allowed to enter into marriage, be required to use a different status (such as a civil union, which either grant equal rights as marriage or limited rights in comparison to marriage), or not have any such rights. A related issue is whether the term marriage should be applied.[176][195][196]

In other animals

In zoology, copulation is often termed as the process in which a male introduces sperm into the female's body. Spiders have separate male and female sexes. Before mating and copulation, a male spins a small web and ejaculates on to it. He then stores the sperm in reservoirs on his large pedipalps, from which he transfers sperm to the female's genitals. Females can store sperm indefinitely.[197]

Many animals which live in the water use external fertilization, whereas internal fertilization may have developed from a need to maintain gametes in a liquid medium in the Late Ordovician epoch. Internal fertilization with many vertebrates (such as reptiles, some fish, and most birds) occur via cloacal copulation (see also hemipenis), while mammals copulate vaginally, and many basal vertebrates reproduce sexually with external fertilization.

However, some terrestrial arthropods do use external fertilization. For primitive insects, the male deposits spermatozoa on the substrate, sometimes stored within a special structure, and courtship involves inducing the female to take up the sperm package into her genital opening; there is no actual copulation. In groups such as dragonflies and spiders, males extrude sperm into secondary copulatory structures removed from their genital opening, which are then used to inseminate the female (in dragonflies, it is a set of modified sternites on the second abdominal segment; in spiders, it is the male pedipalps). In advanced groups of insects, the male uses its aedeagus, a structure formed from the terminal segments of the abdomen, to deposit sperm directly (though sometimes in a capsule called a "spermatophore") into the female's reproductive tract.

Humans, bonobos,[25] chimpanzees and dolphins[26] are species known to engage in heterosexual behaviors even when the female is not in estrus, which is a point in her reproductive cycle suitable for successful impregnation. These species, and others, are also known to engage in homosexual behaviors.[27] Humans, bonobos and dolphins are all intelligent social animals, whose cooperative behavior proves far more successful than that of any individual alone. In these animals, the use of sex has evolved beyond reproduction, to apparently serve additional social functions. Sex reinforces intimate social bonds between individuals to form larger social structures. The resulting cooperation encourages collective tasks that promote the survival of each member of the group.[9]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Sex. Lotus Press. 2006. p. 145. ISBN 8189093592, 9788189093594. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century. Cengage Learning. 2008. p. 423. ISBN 0495553395, 9780495553397. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b c d e Kar (2005). Comprehensive Textbook of Sexual Medicine. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. pp. 107–112. ISBN 8180614050, 9788180614057. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ "Sexual intercourse". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Sexual intercourse". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d "Sexual Intercourse". health.discovery.com. Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ^ International exposure: perspectives on modern European pornography, 1800–2000: p.187

- ^ The Gender of Sexuality: Exploring Sexual Possibilities; Page 76 – Virginia Rutter, Pepper Schwartz – 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g h Diamond, Jared (1992). The rise and fall of the third chimpanzee. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-991380-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g "What is sex? Students' definitions of having sex, sexual partner, and unfaithful sexual behaviour". The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 12: 87–96. 2003.

Recently, researchers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia have investigated university students' definitions of having sex. These studies found that students differ in their opinions of what sexual behaviours constitute having sex (Pitts & Rahman, 2001; Richters & Song, 1999; Sanders & Reinisch, 1999). While the vast majority of respondents (more than 97%) in these three studies included penile-vaginal intercourse in their definition of sex, fewer (between 70% and 90%) respondents considered penile-anal intercourse to constitute having sex. Oral-genital behaviours were defined as sex by between 32% and 58% of respondents.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ a b Paula Kamen (2000). Her Way: Young Women Remake the Sexual Revolution. New York University Press. pp. 74–77. ISBN 0814747337, 9780814747339. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b c The person with HIV/AIDS: nursing perspectives. Springer Publishing Company. 2000. pp. 597 pages. ISBN 8122300049, 9788122300048. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Ann van Sevenant (2005). Sexual Outercourse: A Philosophy of Lovemaking. Peeters. p. 249. ISBN 90-429-1617-6.

- ^ a b c d "Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health" (PDF). World Health Organization. January 2002. p. 4. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

In English, the term 'sex' is often used to mean "sexual activity" and can cover a range of behaviours. Other languages and cultures use different terms, with slightly different meanings.

- ^ Klein, Marty. "The Meaning of Sex". Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, Volume 1 August 10, 1998:. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b c "Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: 2006–2015. Breaking the chain of transmission" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2011. Also see Fact Sheet

- ^ a b "Sexual Risk Factors". aids.gov. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Carpenter, Laura M. (2001). "The Ambiguity of "Having Sex": The Subjective Experience of Virginity Loss in the United States - Statistical Data Included". United States: The Journal of Sex Research. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Bryan Strong, Christine DeVault, Theodore F. Cohen (2010). The Marriage and Family Experience: Intimate Relationship in a Changing Society. Cengage Learning. p. 186. ISBN 0-534-62425-1, 9780534624255. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

Most people agree that we maintain virginity as long as we refrain from sexual (vaginal) intercourse. ... Other research, especially research looking into virginity loss, reports that 35% of virgins, defined as people who have never engaged in vaginal intercourse, have nontheless engaged in one or more other forms of heterosexual activity (e.g. oral sex, anal sex, or mutual masturbation). ... Data indicate that 'a very significant proportion of teens ha[ve] had experience with oral sex, even if they haven't had sexual intercourse, and may think of themselves as virgins'.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bersamin MM, Walker S, Waiters ED, Fisher DA, Grube JW (2005). "Promising to wait: virginity pledges and adolescent sexual behavior". J Adolesc Health. 36 (5): 428–36. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.016. PMC 1949026. PMID 15837347.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Daniel L. Akin. God on Sex: The Creator's Ideas About Love, Intimacy, and Marriage. (2003) B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8054-2596-9

- ^ "Females of almost all species except man will mate only during their fertile period, which is known as estrus, or heat..." Helena Curtis (1975). Biology. Worth Publishers. p. 1065. ISBN 0-87901-040-1.

- ^ Pineda, Leslie Ernest McDonald (2003). McDonald's Veterinary Endocrinology and Reproduction. Blackwell Publishing. p. 597. ISBN 0-8138-1106-6.

- ^ a b c Frans de Waal, "Bonobo Sex and Society", Scientific American (March 1995): 82–86.

- ^ a b c d Bailey NW, Zuk M (2009). "Same-sex sexual behavior and evolution". Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst.). 24 (8): 439–46. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.014. PMID 19539396.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Bruce Bagemihl, Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity (St. Martin's Press, 1999). ISBN 0-312-19239-8

- ^ Balcombe, J. Pleasurable Kingdom: Animals and the Nature of Feeling Good. Macmillan, New York, 2007. 360 pp. ISBN 1-4039-8602-9 [1]

- ^ a b c The Encyclopedia of Mental Health. Infobase Publishing. 2008. p. 111. ISBN 0816064547, 9780816064540. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Coitus". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Coitus". dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ "Copulation". medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ "Copulation". thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ Laura M. Carpenter (2005). Virginity lost: an intimate portrait of first sexual experiences. NYU Press. pp. 295 pages. ISBN 0-8147-1652-0, 9780814716526. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

Many studies, moreover, seemed uncritically to lump nonvirgin teens (so designated if they'd had vaginal sex) together with their alcohol–and drug–using peers 'at risk' for negative outcomes from unintended pregnancy and STIs (sexually transmitted infections) to academic failure and low self-esteem.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b c d Cox, Lauren (March 8, 2010). "Study: Adults Can't Agree What 'Sex' Means". ABC.com. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^

Our Sexuality. Cengage Learning. 2010. pp. 286–289. ISBN 0495812943, 9780495812944. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

Noncoital forms of sexual intimacy, which have been called outercourse, can be a viable form of birth control. Outercourse includes all avenues of sexual intimacy other than penile–vaginal intercourse, including kissing, touching, mutual masturbation, and oral and anal sex.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b Frederick C. Wood (1968, Digitized July 23, 2008). Sex and the new morality. Association Press, 1968/Original from the University of Michigan. pp. 157 pages.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Friedman, Mindy (September 20, 2005). "Sex on Tuesday: Virginity: A Fluid Issue". The Daily Californian. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Mark Regnerus (2007). "The Technical Virginity Debate: Is Oral Sex Really Sex?". Forbidden Fruit: Sex & Religion in the Lives of American Teenagers. Oxford University Press US. pp. 290 pages. ISBN 978-0-19-532094-7.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Joseph Gross, Michael (2003). Like a Virgin. The Advocate, Here Publishing. pp. 104 pages, Page 44. 0001-8996. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Steven Gregory Underwood (2003). Gay men and anal eroticism: tops, bottoms, and versatiles. Psychology Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-56023-375-6. 1560233753, 9781560233756. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ^ Joe Perez (2006). Rising Up. Lulu.com. p. 248. ISBN 1-4116-9173-3, 9781411691735. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Dolby, Tom (February 2004). "Why Some Gay Men Don't Go All The Way". Out. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Hanne Blank (2008). Virgin: The Untouched History. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 304 pages. ISBN 1-59691-011-9, 9781-59691-011-9. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Karen Bouris (1995). The first time: what parents and teenage girls should know about "losing your virginity". Conari Press. p. 198. ISBN 0-943233-93-3, 9780943233932.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Jayson, Sharon (2005-10-19). "'Technical virginity' becomes part of teens' equation". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "'I Want a Better Orgasm!'". WebMD. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Psychiatry: Diagnosis & therapy. A Lange clinical manual. Appleton & Lange (Original from Northwestern University). 1993, Digitized Oct 29, 2010. pp. 544 pages. ISBN 0-8385-1267-4, 9780838512678. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

The amount of time of sexual arousal needed to reach orgasm is variable — and usually much longer — in women than in men; thus, only 20–30% of women attain a coital climax. b. Many women (70–80%) require manual clitoral stimulation...

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help); horizontal tab character in|publisher=at position 32 (help) - ^ Mah, Kenneth; Binik, Yitzchak M (2001, available online on July 17, 2001). "The nature of human orgasm: a critical review of major trends". Clinical Psychology Review. 21 (6): 823–856. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00069-6.

Women rated clitoral stimulation as at least somewhat more important than vaginal stimulation in achieving orgasm; only about 20% indicated that they did not require additional clitoral stimulation during intercourse.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kammerer-Doak, Dorothy; Rogers, Rebecca G. (2008, available online on May 16, 2008). "Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 35 (2): 169–183. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2008.03.006. PMID 18486835.

Most women report the inability to achieve orgasm with vaginal intercourse and require direct clitoral stimulation ... About 20% have coital climaxes...

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Federation of Feminist Women’s Health Centers (1991). A New View of a Woman’s Body. Feminist Heath Press. p. 46. ISBN 0-929945-0-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ O'Connell HE, Sanjeevan KV, Hutson JM (2005). "Anatomy of the clitoris". The Journal of Urology. 174 (4 Pt 1): 1189–95. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd. PMID 16145367.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The technique of coital alignment and its relation to female orgasmic response and simultaneous orgasm". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 14(2): 129–141. 1988. doi:10.1080/00926238808403913. PMID 3204637.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laysource=,|laysummary=, and|laydate=(help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "The coital alignment technique and directed masturbation: a comparative study on female orgasm". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 21(1): 21–29. 1995. doi:10.1080/00926239508405968. PMID 7608994.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laysource=,|laysummary=, and|laydate=(help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Dr. John Dean and Dr. David Delvin. "Anal sex". Netdoctor.co.uk. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ^ "Anal Sex". Health.discovery.com. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ^ a b Hite, Shere (2003). The Hite Report: A Nationwide Study of Female Sexuality. New York, NY: Seven Stories Press. pp. 512 pages. ISBN 1-58322-569-2, 9781583225691. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Carroll, Janell L. (2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. pp. 118, and 252. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

The clitoral glans is a particularly sensitive receptor and transmitter of sexual stimuli. In fact, the clitoris, although much smaller than the penis, has twice the number of nerve endings (8,000) as the penis (4,000) and has a higher concentration of nerve fibers than anywhere else on the body... In fact, most women do not enjoy direct stimulation of the glans and prefer stimulation through the [hood]... The majority of women enjoy a light caressing of the shaft of the clitoris, together with an occasional circling of the [clitoral glans], and maybe digital (finger) penetration of the vagina. Other women dislike direct stimulation and prefer to have the [clitoral glans] rolled between the lips of the labia. Some women like to have the entire area of the vulva caressed, whereas others like the caressing to be focused on the [clitoral glans]. Women report that clitoral stimulation feels best when the fingers are well lubricated.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (1997). Why Is Sex Fun?. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-03127-7.

- ^ Ozolins, John. "Surrogacy: Exploitation or Violation of Intimacy?". Boston University. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

This concern for the unity of the spouses seems to be why artificial insemination of a surrogate in cases where the wife cannot supply a fertile ovum is preferred, rather than natural insemination, since it does not involve any relationship with the surrogate

- ^ "Not Every Pregnancy is Welcome". The world health report 2005 – make every mother and child count. World Health Organization. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Get "In the Know": 20 Questions About Pregnancy, Contraception and Abortion". Guttmacher Institute. 2005. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Ventura, SJ, Abma, JC, Mosher, WD, & Henshaw, S. (2007-11-16). "Estimated pregnancy rates for the United States, 1990–2000: An Update. National Vital Statistics Reports, 52 (23)" (PDF). cdc.gov. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Christine Webber, psychotherapist and Dr David Delvin. "Talking to pre-adolescent children about sex". Broaching the subject. Net Doctor. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ^ Berkowitz, D & Marsiglio, W (2007). Gay Men: Negotiating Procreative, Father, and Family Identities. Journal of Marriage and Family 69 (May 2007): 366–381

- ^ a b

Joan M. Burda (2008). Gay, lesbian, and transgender clients: a lawyer's guide. American Bar Association. p. 437. ISBN 1-59031-944-3, 9781590319444. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Tagami T, Matsubara Y, Hanada H, Naito M. (June 1997). "Differentiation of female chicken primordial germ cells into spermatozoa in male gonads". Dev. Growth Differ. 39 (3): 267–71. doi:10.1046/j.1440-169X.1997.t01-2-00002.x. PMID 9227893.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Japanese scientists produce mice without using sperm". Washington Post. Sarasota Herald-Tribune. April 22, 2004. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ Elizabeth Bernstein, Laurie Schaffner (2005). Regulating sex: the politics of intimacy and identity. Perspectives on gender. Psychology Press. p. 313. ISBN 0-415-94869-X, 9780415948692. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ "Sexual and Reproductive Health: Women and Men". Guttmacher Institute. 2002. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ "Sexual Health Statistics for Teenagers and Young Adults in the United States" (PDF). Kaiser Family Foundation. 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Contraceptive Use". Guttmacher Institute. 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Denis Campbell (January 22, 2006). "No sex please until we're at least 17 years old, we're British". The Observer.

- ^ "Teen Sex Survey". Channel 4. 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ^ Jonathan Thompson (November 12, 2006). "New safe sex ads target teens 'on the pull'". The Independent.

- ^ a b "Findings from the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior, Centre for Sexual Health Promotion, Indiana University". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7, Supplement 5.: 4 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ a b "Premature ejaculation". Mayo Clinic.com. Retrieved 2007-03-02.

- ^ a b "Anorgasmia in women". Mayo Clinic.com. Retrieved 2010-11-23.

- ^ a b c d Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century. Cengage Learning. 2011. p. 386. ISBN 1-111-18663-4, 9781111186630. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b The Kinsey Institute New Report On Sex. Macmillan. 1991. pp. 129–130. ISBN 0312063865, 9780312063863. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Corty, E., & Guardiani, J. (2008) Canadian and American Sex Therapists' Perceptions of Normal and Abnormal Ejaculatory Latencies: How Long Should Intercourse Last?. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(5), 1251–1256. [[doi (identifier)|doi]]:[https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1743-6109.2008.00797.x 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00797.x]". .interscience.wiley.com. 2008-03-04. Retrieved 2010-11-23.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title=|title=at position 215 (help) - ^ "Sex therapists: Best sex is 7 to 13 min". Upi.com. March. 5, 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Frank JE, Mistretta P, Will J (2008). "Diagnosis and treatment of female sexual dysfunction". American family physician. 77 (5): 635–42. PMID 18350761.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States". University of Chicago Press (Also reported in the companion volume, Michael et al, Sex in America: A Definitive Survey.). 1994. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Cohen D, Amsel R. ( 2003) Etiological correlates of vaginismus: sexual and physical abuse, sexual knowledge, sexual self-schema, and relationship adjustment. J Sex Marital Ther.29:47–59.

- ^ Ward E, Ogden J. (1994) Experiencing Vaginismus: sufferers beliefs about causes and effects. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 9 (1): 33–45.

- ^ a b Frank JE, Mistretta P, Will J (2008). "Diagnosis and treatment of female sexual dysfunction". Am Fam Physician. 77 (5): 635–42. PMID 18350761.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shafik A.; El-Sibai O.Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Volume 20, Number 3, 1 May 2000 , pp. 300–302(3)

- ^ Binik YM (2005). "Should dyspareunia be retained as a sexual dysfunction in DSM-V? A painful classification decision". Arch Sex Behav. 34 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-0998-4. PMID 15772767.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Peckham BM, Maki DG, Patterson JJ, Hafez GR (1986). "Focal vulvitis: a characteristic syndrome and cause of dyspareunia. Features, natural history, and management". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 154 (4): 855–64. PMID 3963075.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schouten BW, Bohnen AM, Groeneveld FP, Dohle GR, Thomas S, Bosch JL (2010). "Erectile dysfunction in the community: trends over time in incidence, prevalence, GP consultation and medication use—the Krimpen study: trends in ED". J Sex Med. 7 (7): 2547–53. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01849.x. PMID 20497307.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heidelbaugh JJ (2010). "Management of erectile dysfunction". Am Fam Physician. 81 (3): 305–12. PMID 20112889.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel. AUA guideline on the pharmacologic management of premature ejaculation. Linthicum (MD): American Urological Association, Inc.; 2004. 19 p.[2]

- ^ Riley, A.; Segraves, RT (2006). "Treatment of Premature Ejaculation". Int J. Clin Pract. 60 (6). Blackwell Publishing: 694–697. doi:10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00818.x. PMID 16805755. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hengeveld VW, Waldinger MD; Hengeveld, MW; Zwinderman, AH; Olivier, B; et al. (1998). "Effect of SSRI antidepressants on ejaculation: a double blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study with fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 18 (4): 274–281. doi:10.1097/00004714-199808000-00004. PMID 9690692.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ a b Williamson, Gail M. (01). "Perceived Impact of Limb Amputation on Sexual Activity: A Study of Adult Amputees". The Journal of Sex Research. 33 (3). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (Taylor & Francis Group): 221–230. doi:10.1080/00224499609551838. ISSN 0022-4499. JSTOR 3813582. OCLC 39109327.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Majiet, Shanaaz (01). "Disabled Women and Sexuality". Agenda (19). Agenda Feminist Media: 43–44. doi:10.2307/4065995. JSTOR 4065995.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ Dewolfe, Deborah J. (August 1, 1982). "Sexual Therapy for a Woman with Cerebral Palsy: A Case Analysis". The Journal of Sex Research. 18 (3). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (Taylor & Francis Group): 253–263. doi:10.1080/00224498209551151. ISSN 0022-4499. JSTOR 3812217. OCLC 39109327.