Cumin: Difference between revisions

Removed redundancy |

|||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

=== Cultivation areas === |

=== Cultivation areas === |

||

The main producer and consumer of cumin is India. It produces 70% of the world production and consumes 90% of its own production (which is 63% of the world production). Other producers are Syria (7%), Turkey (6%) and Iran (6%). The remaining 11% production is assigned to other countries |

The main producer and consumer of cumin is India. It produces 70% of the world production and consumes 90% of its own production (which is 63% of the world production). Other producers are Syria (7%), Turkey (6%) and Iran (6%). The remaining 11% production is assigned to other countries. Totally, around 300,000 tons of cumin per year are produced worldwide. 2007 India produced around 175'000 tons of cumin on an area of about 410,000 ha. I.e. the average yield is 0.43 tons per ha.<ref name="a" /> |

||

=== Climatic requirements === |

=== Climatic requirements === |

||

Revision as of 20:23, 7 February 2014

| Cumin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | C. cyminum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cuminum cyminum | |

Cumin (/ˈkjuːm[invalid input: 'ɨ']n/ or UK: /ˈkʌm[invalid input: 'ɨ']n/, US: /ˈkuːm[invalid input: 'ɨ']n/; sometimes spelled cummin; Cuminum cyminum) is a flowering plant in the family Apiaceae, native from the east Mediterranean to India. Its seeds (each one contained within a fruit, which is dried) are used in the cuisines of many different cultures, in both whole and ground form.

Etymology

The English "cumin" derives from the Old English cymen (or Old French cumin), from Latin cuminum,[2] which is the latinisation of the Greek κύμινον (kuminon),[3] cognate with Hebrew כמון (kammon) and Arabic كمون (kammun).[4] Forms of this word are attested in several ancient Semitic languages, including kamūnu in Akkadian.[5] The ultimate source is the Sumerian word gamun.[6] The earliest attested form of the word κύμινον (kuminon) is the Mycenaean Greek ku-mi-no, written in Linear B syllabic script.[7]

<-- ==Other names== ar:كمون, az:Adi cirə, bg:Кимион, br:Koumin, ca:Comí, ceb:Komino, cs:Kmín římský, da:Spidskommen, de:Kreuzkümmel, dv:ދިރި, el:Κύμινο, es:Cuminum cyminum, eo:Kumino, eu:Kumino, fa:زیره سبز, fr:Cumin, gl:Comiño, gu:જીરું, ko:커민, hi:जीरा, io:Kumino, id:Jintan putih, it:Cuminum cyminum, he:כמון, jv:Jinten putih, ka:ძირა, ku:Reşke, hu:Római kömény, ml:ജീരകം, mr:जिरे, ms:Jintan putih, my:ဇီယာ, nl:Komijn, ne:जीरा, ja:クミン, no:Spisskummen, or:ଜିରା, pl:Kmin rzymski, pt:Cominho, ro:Chimion, ru:Зира (растение), sa:जीरकम्, simple:Cumin, sl:Orientalska kumina, su:Jinten bodas, fi:Roomankumina, sv:Spiskummin, tl:Komino, ta:சீரகம், te:జీలకర్ర, tr:Kimyon, uk:Зіра (рослина), vi:Thì là Ai Cập, zh:孜然-->

Other names

In Hindi and Bengali it is known as jira.

Description

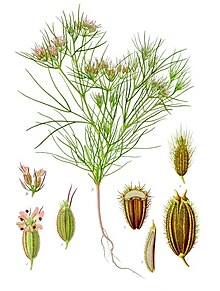

Cumin is the dried seed of the herb Cuminum cyminum, a member of the parsley family. The cumin plant grows to 30–50 cm (0.98–1.64 ft) tall and is harvested by hand. It is an annual herbaceous plant, with a slender, glabrous, branched stem which is 20–30 cm tall and has a diameter of 3 to 5 cm.[8] Each branch has 2 to 3 sub-branches. All the branches attain the same height, therefore the plant has a uniform canopy.[8] The stem is coloured grey or dark green. The leaves are 5–10 cm long, pinnate or bipinnate, with thread-like leaflets. The flowers are small, white or pink, and borne in umbels. Each umbel has 5 to 7 umbellts.[8] The fruit is a lateral fusiform or ovoid achene 4–5 mm long, containing two mericarps with a single seed.[8] Cumin seeds have eight ridges with oil canals.[8] They resemble caraway seeds, being oblong in shape, longitudinally ridged, and yellow-brown in color, like other members of the umbelliferae family such as caraway, parsley and dill.

History

Cumin has been in use since ancient times. Seeds excavated at the Indian site have been dated to the second millennium BC. They have also been reported from several New Kingdom levels of ancient Egyptian archaeological sites.[9] In the ancient Egyptian civilisation cumin was used as spice and as preservative in mummification.[8]

Originally cultivated in Iran and the Mediterranean region,[citation needed] cumin is mentioned in the Bible in both the Old Testament (Isaiah 28:27) and the New Testament (Matthew 23:23). The ancient Greeks kept cumin at the dining table in its own container (much as pepper is frequently kept today), and this practice continues in Morocco. Cumin was also used heavily in ancient Roman cuisine. It was introduced to the Americas by Spanish and Portuguese colonists. There are several different types of cumin but the most famous ones are black and green cumin which are both used in Persian cuisine.

Today, the plant is mostly grown in China, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Iran, Turkey, Morocco, Egypt, Syria, Mexico, Chile and India. Since cumin is often used as part of birdseed and exported to many countries, the plant can occur as a rare casual in many territories including Britain.[10] Cumin occurs as a rare casual in the British Isles, mainly in Southern England; but the frequency of its occurrence has declined greatly. According to the Botanical Society of the British Isles' most recent Atlas, only one record has been confirmed since 2000.

In India, cumin has been used for millennia as a traditional ingredient of innumerable kormas, masalas, soups, and other spiced gravies.

Cultivation and production [11]

Cultivation areas

The main producer and consumer of cumin is India. It produces 70% of the world production and consumes 90% of its own production (which is 63% of the world production). Other producers are Syria (7%), Turkey (6%) and Iran (6%). The remaining 11% production is assigned to other countries. Totally, around 300,000 tons of cumin per year are produced worldwide. 2007 India produced around 175'000 tons of cumin on an area of about 410,000 ha. I.e. the average yield is 0.43 tons per ha.[8]

Climatic requirements

Cumin is a drought tolerant, tropic or semi-tropic crop. Its origin is most probably Egypt, Turkmenistan and the east Mediterranean. Cumin has a short growth season of 100 – 120 days.[12] The optimum growth temperature ranges are between 25° and 30°C.[8] The Mediterranean climate is most suitable for its growth; cumin requires a moderatly cool and dry climate. Cultivation of cumin requires a long, hot summer of three to four months. Upon low temperatures leaf color changes from green to purple. High temperature might reduce growth period and induce early ripening. In India, Cumin is sown from October until the begin of December and harvesting starts in February.[8] In Syria and Iran Cumin is sown from mid-November until mid-December (extensions up to mid-January are possible) and harvested in June/July.[8]

Cultivation parameters

Cumin is grown from seeds. The seeds need 2° up to 5°C for emergence, an optimum of 20°C – 30° is suggested. Cumin is vulnerable to frost damage, especially at flowering and early seed formation stages.[8] Methods to reduce frost damage are spraying with sulfuric acid (0.1%), irrigating the crop prior to frost incidence, setting up windbreaks or creating an early morning smoke cover.[8] The seedlings of cumin are rather small and their vigor is low. Soaking the seeds for 8 hours before sowing enhances germination.[8] For an optimal plant population a sowing density of 12 – 15 kg / ha is recommended.[8] Fertile, sandy, loamy soils with good aeration, proper drainage and high oxygen availability are preferred. The pH optimum of the soil ranges from pH 6.8-8.3.[8] Cumin seedlings are sensitive to salinity [12] and emergence from heavy soils is rather difficult for cumin. Therefore a proper seedbed preparation (smooth seed bed) is crucial for optimal establishment of cumin.

Two sowing methods are used for cumin, broadcasting and line sowing.[8] For broadcast sowing, the field is divided into beds and the seeds are uniformly broadcast in this bed. Afterwards they are covered with soil using a rake. For line sowing shallow furrows are prepared with hooks in a distance of 20 to 25 cm. The seeds are afterwards placed in these furrows and covered with soil. Line sowing offers advantages for intercultural operations such as weeding, hoeing or spraying.[8] The recommended sowing depth is 1–2 cm and the recommended sowing density is around 120 plants/m2. The water requirements of cumin are lower than those of many other species.[8] Despite, cumin is often irrigated after sowing to be sure that enough moisture is available for seedling development. The amount and frequency of irrigation depends on the climate conditions.[8]

Cultivation management

The relative humidity in the center of origin of cumin is rather low. High relative humidity (i.e. wet years) favours fungal diseases. Cumin is especially sensitive to Alternaria blight and Fusarium wilt. Early sown crops are exhibit stronger disease effects than late sown crops. The most important disease is wilt caused by Fusarium resulting in yield losses up to 80%.[8] Fusarium is seed- or soil-borne and it requires distinct soil temperatures for development of epidemics.[8] Inadequate fertilization might favour Fusarium epidemics.[8] Cumin blight (Alternaria) appears in the form of dark brown spots on leaves and stems.[8] When the weather is cloudy after flowering the incidence of the disease is increased.[8] Another, but less important disease is powdery mildew. Incidence of powdery mildew in early development can cause drastic yield losses because no seeds are formed.[8] Later in development powdery mildew causes discoloured, small seeds.[8]

Pathogens can lead to high reductions in crop yield. Cumin can be attacked by aphids (Myzus persicae) at flowering stage. They suck the sap of the plant from tender parts and flowers. The plant becomes yellow, the seed formation is reduced (yield reduction) and the quality of the harvested product decreases. Heavily infested plant parts should be removed. Other important pests are the mites (Petrobia latens) which frequently attack the crop. Since the mites mostly feed on young leaves, the infestation is more severe on young inflorescences.

The open canopy of cumin is another problem. Only a low proportion of the incoming light is absorbed. The Leaf Area Index (LAI) of cumin is low (approximately 1.5). This might be a problem because weeds can compete with cumin for essential resources such as water and light and thereby lower yield. The slow growth and a short stature of cumin favours weed competition additionally.[8] Two hoeing and weeding sessions (30 and 60 days after sowing) are needed for the control of weeds. During the first weeding session (30 days after sowing) thinning should be done as well to remove excess plants. The use of pre-plant or pre-emergence herbicides is very effective in India.[8] But this kind of herbicide application requires soil moisture for a successful weed control.

Fertilization recommendations in India[8]

- 20 kg phosphate / ha (sowing)

- 30 kg N / ha, either

- single dose (30 days after sowing) or

- two doses (30 and 60 days after sowing)

Fertilization recommendations in Syria[8]

- 50 kg triple super phosphate (at planting)

- 50 kg urea (at planting)

Breeding of cumin [11]

Cumin is a diploid species and with 14 chromosomes (i.e. 2n = 14). The chromosomes of the different varieties have morphological similarities and there is no distinct variation in length and volume. Most of the varieties available today are selections.[8] The variabilities of yield and yield components are high. Varieties are developed by sib mating in enclosed chambers[8] or by biotechnoloy. Cumin is a cross-pollinator, i.e. the breeds are already hybrids. Therefore, methods used for breeding are in vitro regenerations, DNA technologies and gene transfers. The in vitro cultivation of cumin allows the production of genetically identical plants. The main sources for the explants used in vitro regenerations are embryos, hypocotyl, shoot internodes, leaves and cotyledons. One goal of cumin breeding is to improve its resistance to biotic (fungal diseases) and abiotic (cold, drought, salinity) stresses. The potential genetic variability for conventional breeding of cumin is limited and research about cumin genetics is scarce.[13]

Uses

Cumin seeds are used as a spice for their distinctive flavor and aroma. It is globally popular and an essential flavoring in many cuisines, particularly South Asian, Northern African and Latin American cuisines. Cumin can be found in some cheeses, such as Leyden cheese, and in some traditional breads from France. It is commonly used in traditional Brazilian cuisine. Cumin can be an ingredient in chili powder (often Tex-Mex or Mexican-style), and is found in achiote blends, adobos, sofrito, garam masala, curry powder, and bahaarat.

Cumin can be used ground or as whole seeds. It helps to add an earthy and warming feeling to food, making it a staple in certain stews and soups, as well as spiced gravies such as chili. It is also used as an ingredient in some pickles and pastries.[14]

Medicinal uses

In Sanskrit, Cumin is known as Jiraka. Jira means “that which helps digestion". In Ayurvedic system of medicine,dried Cumin seeds are used for medicinal purposes. The dried cumin seeds are powdered and used in different forms like kashaya (decoction), arishta (fermented decoction), vati(tablet/pills), and processed with ghee (a semi-fluid clarified butter). It is used internally and sometimes for external application also. It is known for its actions like enhancing appetite, taste perception, digestion, vision, strength, and lactation. It is used to treat diseases like fever, loss of appetite, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal distension, edema and puerperal disorders.[15]

Secondary metabolites

Cuminaldehyde, cymene and terpenoids are the major volatile components of cumin. Results of a study conducted in India showed that cumin can be used as an antioxidant.[16] The antioxidative potential is correlated with the phenol content of cumin.[16] Cuminaldehyde has also antimicrobial and antifungal properties which could be shown e.g. with Escherichia coli and Penicillium chrysogenum.[17]

Nutritional value

| Nutritional value per | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1,567 kJ (375 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

44.24 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 2.25 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 10.5 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

22.27 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturated | 1.535 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 14.04 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 3.279 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

17.81 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 8.06 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reference [18] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[19] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[20] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Although cumin seeds contain a relatively large percentage of iron, extremely large quantities of cumin would need to be consumed for it to serve as a significant dietary source (see nutrition data).

According to the USDA, one tablespoon of cumin spice contains:[21]

- Calories (kcal): 22

- Fat (g): 1.34

- Carbohydrates (g): 2.63

- Fiber (g): 0.6

- Protein (g): 1.07

Confusion with other spices

Cumin is sometimes confused with caraway (Carum carvi), another umbelliferous spice. Cumin, though, is hotter to the taste, lighter in color, and larger. Many European languages do not distinguish clearly between the two. Many Slavic and Uralic languages refer to cumin as "Roman caraway". Examples include Czech: kmín – caraway, římský kmín -cumin; Polish: kminek – caraway, kmin rzymski – cumin; Hungarian: kömény – caraway, római kömény – cumin. Finnish: kumina – caraway, roomankumina – cumin, although sometimes also called juustokumina, cheese caraway. In Norwegian, caraway is called both karve and kummin/kømming while cumin is spisskummen, from the word spise, to eat. Similarly in Swedish and Danish, caraway is kummin/kommen, while cumin is spiskummin/spidskommen. In German, Kümmel stands for caraway and Kreuzkümmel denotes cumin. In Icelandic, caraway is kúmen, while cumin is kúmín. In Romanian, chimen is caraway, while chimion is cumin.

The distantly related Bunium persicum and the unrelated Nigella sativa are both sometimes called black cumin (q.v.).

Aroma profile

Cumin's distinctive flavor and strong, warm aroma are due to its essential oil content. Its main constituent aroma compounds are cuminaldehyde (a promising agent against alpha-synuclein aggregation) and cuminic alcohol. Other important aroma compounds of toasted cumin are the substituted pyrazines, 2-ethoxy-3-isopropylpyrazine, 2-methoxy-3-sec-butylpyrazine, and 2-methoxy-3-methylpyrazine. Other components include γ-terpinene, safranal, p-cymene and β-pinene.[22][23][24]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2009) |

Images

-

Dry, whole cumin fruit (or seed)

-

Whole cumin seeds and ground cumin

-

Commercially packaged whole and ground cumin seeds

-

Close up of dried cumin seeds

Notes and references

- ^ "Cuminum cyminum information from NPGS/GRIN". www.ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ^ cuminum, Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ κύμινον, known as saunf or سونف in Pakistan. Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ cumin, Persian: Zeereh زیره , Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ "Kamūnu." premiumwanadoo.com.

- ^ Anton Deimel, Orientalia Old Series 13 (1924) 330.

- ^ Palaeolexicon, Word study tool of ancient languages

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af E. V. Divakara Sastry, Muthuswamy Anandaraj. "Cumin, Fennel and Fenugreek". SOILS, PLANT GROWTH AND CROP PRODUCTION (PDF). Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS). Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of plants in the Old World, third edition (Oxford: University Press, 2000), p. 206

- ^ Bird Seed Aliens in Britain

- ^ a b M. Kafi, M.H. Rashed Mohassel, A. Koocheki, M. Nassiri, ed. (2006). Cumin (Cuminum cyminum) Production and Processing (in Englisch). Enfield, New Hampshire, USA: Science Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57808-504-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b Roodbari, Nasim (2013). "The Effect of Salinity Stress on Germination and Seedling Growth of Cumin (Cuminum Cyminum L.)" (PDF). Journal of Agriculture and Food Technology. 5 (3): 1–4. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ebrahimie, Esmaeil (2003). "A rapid and efficient method for regeneration of plantlets from embryo explants of cumin (Cuminum cyminum)". Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture. 75. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers: 19–25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ M. G. Kains (1912). American Agriculturist (ed.). Culinary Herbs: Their Cultivation Harvesting Curing and Uses (English). Orange Judd Company.

{{cite book}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help); Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ National R&D facility for Rasayana - Jiraka

- ^ a b Thippeswamy, N. B. (2005). "Antioxidant potency of cumin varieties—cumin, black cumin and bitter cumin—on antioxidant systems". Eur Food Res Technol. 220: 472–476. doi:10.1007/s00217-004-1087-y.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Shetty, R.S. (1994). "Antimicrobial properties of cumin". World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology. 10. Rapid Communications of Oxford Ltd: 232–233.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ United States Department of Agriculture. "Cumin Seed". Agricultural Research Service USDA. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Search the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. Nal.usda.gov. Retrieved on 2011-11-26.

- ^ Li, Rong (2004). "Chemical composition of the essential oil of Cuminum cyminum L. from China". Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 19 (4): 311–313. doi:10.1002/ffj.1302.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wang, Lu; et al. (2009). "Ultrasonic nebulization extraction coupled with headspace single drop microextraction and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry for analysis of the essential oil in Cuminum cyminum L". Analytica Chimica Acta. 647 (1): 72–77. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2009.05.030. PMID 19576388.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Iacobellis, Nicola S.; et al. (2005). "Antibacterial Activity of Cuminum cyminum L. and Carum carvi L. Essential Oils". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (1): 57–61. doi:10.1021/jf0487351. PMID 15631509.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)

External links