Soviet invasion of Poland: Difference between revisions

Fixed data: We can't considerate Molotov-Ribbentrop pact as a clue of iii Reich support of Soviet invasion since it occured without the support from iii reich's army. Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Undid revision 811491739 by 85.136.62.115 (talk) See for e.g Battle of Lwów (1939) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

|combatant1 ={{flagicon|POL|1928}} [[Second Polish Republic|Poland]] |

|combatant1 ={{flagicon|POL|1928}} [[Second Polish Republic|Poland]] |

||

|combatant2 ={{flag|Soviet Union|1923}} |

|combatant2 ={{flag|Soviet Union|1923}} |

||

''Supported by:''<br>{{flag|Nazi Germany}} |

|||

|commander1 ={{ubl |

|commander1 ={{ubl |

||

|[[Edward Rydz-Śmigły]] |

|[[Edward Rydz-Śmigły]] |

||

Revision as of 12:13, 23 November 2017

| Soviet invasion of Poland | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Invasion of Poland in World War II | |||||||||

Soviet parade in Lwów, 1939 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

20,000 Border Protection Corps,[1][Note 1] 250,000 Polish Army.[2][Note 2] |

466,516–800,000 troops[2][3] 33+ divisions 11+ brigades 4,959 guns 4,736 tanks 3,300 aircraft | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

3,000–7,000 dead or missing,[1][4] up to 20,000 wounded.[1][Note 3] 99,149 captured[5]: 85 |

1,475–3,000 killed or missing 2,383–10,000 wounded.[Note 4] | ||||||||

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a Soviet military operation that started without a formal declaration of war on 17 September 1939. On that morning, 16 days after Germany invaded Poland from the west, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east. The invasion and the battle lasted for the following 20 days and ended on 6 October 1939 with the two-way division and annexation of the entire territory of the Second Polish Republic by both Germany and the Soviet Union.[7] The joint German-Soviet invasion of Poland was secretly agreed to in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, signed on 23 August 1939.[8]

The Red Army, which vastly outnumbered the Polish defenders, achieved its targets by using strategic and tactical deception. Some 230,000 Polish prisoners of war had been captured.[4][9] The campaign of mass persecution in the newly acquired areas began immediately. In November 1939 the Soviet government ostensibly annexed the entire Polish territory under its control. Some 13.5 million Polish citizens who fell under the military occupation were made into new Soviet subjects following mock elections conducted by the NKVD secret police in the atmosphere of terror,[10][11] the results of which were used to legitimize the use of force. A Soviet campaign of political murders and other forms of repression, targeting Polish figures of authority, such as military officers, police and priests, began with a wave of arrests and summary executions.[Note 5][12][13] Over the next year and a half, the Soviet NKVD sent hundreds of thousands of people from eastern Poland to Siberia and other remote parts of the Soviet Union in four major waves of deportation between 1939 and 1941.[Note 6]

Soviet forces occupied eastern Poland until the summer of 1941, when they were driven out by the invading German army in the course of Operation Barbarossa. The area was under German occupation until the Red Army reconquered it again in the summer of 1944. An agreement at the Yalta Conference permitted the Soviet Union to annex almost all of their Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact portion of the Second Polish Republic, "compensating" the People's Republic of Poland with the southern half of East Prussia and territories east of the Oder–Neisse line.[16] The Soviet Union enclosed most of the annexed territories into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.[16]

After the end of World War II in Europe, the USSR signed a brand new border agreement with the Polish communists on 16 August 1945. This agreement recognized the status quo as the new official border between the two countries with the exception of the region around Białystok and a minor part of Galicia east of the San river around Przemyśl, which were returned to Poland later on.[17]

Prelude

Several months before the invasion, in early 1939 the Soviet Union began strategic alliance negotiations with the United Kingdom, France, Poland, and Romania against the crash militarization of Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler. The USSR played a double game by secretly engaging in parallel talks with Germany. The negotiations with the Western democracies failed as expected, when the Soviet Union insisted that Poland and Romania give Soviet troops transit rights through their territory as part of a collective security arrangement.[18] The terms were rejected, thus giving Josef Stalin a free hand in pursuing the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Adolf Hitler, signed on 23 August 1939. The non-aggression pact contained a secret protocol dividing Northern and Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence in the event of war.[19] One week after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, German forces invaded Poland from the west, north, and south on 1 September 1939. Polish forces gradually withdrew to the southeast where they prepared for a long defence of the Romanian Bridgehead and awaited the French and British support and relief that they were expecting. On 17 September 1939 the Soviet Red Army invaded the Kresy regions in accordance with the secret protocol.[20][Note 7]

At the opening of hostilities several Polish cities including Dubno, Łuck and Włodzimierz Wołyński let the Red Army in peacefully, convinced that it was marching on in order to fight the Germans. General Juliusz Rómmel of the Polish Army issued an unauthorised order to treat them like an ally before it was too late.[23] The Soviet government announced it was acting to protect the Ukrainians and Belarusians who lived in the eastern part of Poland, because the Polish state – according to Soviet propaganda – had collapsed in the face of the Nazi German attack and could no longer guarantee the security of its own citizens.[24][25][26][27] Facing a second front, the Polish government concluded that the defence of the Romanian Bridgehead was no longer feasible and ordered an emergency evacuation of all uniformed troops to then-neutral Romania.[1]

Poland between world wars

The result of the Paris Peace Conference (1919) did little to decrease the territorial ambitions of parties in the region. Józef Piłsudski sought to expand the Polish borders as far east as possible in an attempt to create a Polish-led federation to counter any potential imperialist intentions on the part of Russia or Germany.[28] At the same time, the Bolsheviks began to gain the upper hand in the Russian Civil War and started to advance westward towards the disputed territories with the intent of assisting other Communist movements in Western Europe.[29] The border skirmishes of 1919 progressively escalated into the Polish–Soviet War in 1920.[30] Following the Polish victory at the Battle of Warsaw, the Soviets sued for peace and the war ended with an armistice in October 1920.[31] The parties signed the formal peace treaty, the Peace of Riga, on 18 March 1921, dividing the disputed territories between Poland and Soviet Russia.[32] In an action that largely determined the Soviet-Polish border during the interwar period, the Soviets offered the Polish peace delegation territorial concessions in the contested borderland areas, closely resembling the border between the Russian Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth before the first partition of 1772.[33] In the aftermath of the peace agreement, Soviet leaders largely abandoned the cause of international revolution and did not return to the concept for approximately 20 years.[34] The Conference of Ambassadors and the international community (with the exception of Lithuania) recognized Poland's eastern frontiers in 1923.[35][36]

Treaty negotiations

Germany marched into Prague on 15 March 1939. In mid-April, the Soviet Union, Britain and France began trading diplomatic suggestions regarding a political and military agreement to counter potential further German aggression.[37][38] Poland did not participate in these talks.[39] The tripartite discussions focused on possible guarantees to participating countries should German expansionism continue.[40] The Soviets did not trust the British or the French to honour a collective security agreement, because they had already failed to react against the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War and protect Czechoslovakia from dismemberment. The Soviet Union also suspected that Britain and France would seek to remain on the sidelines of any potential Nazi-Soviet conflict.[41] In reality however, Stalin had been conducting secret talks with Nazi Germany already since 1936 through his emissaries, and all along a deal with Hitler remained his first diplomatic choice, wrote Robert C. Grogin (author of Natural Enemies).[42] The Soviet Union sought nothing short of an ironclad guarantee against losing its sphere of influence,[43] and insisted on stretching the so-called buffer zone from Finland to Romania, in the event of an attack.[44][45] The Soviets demanded the right to enter these countries in the event of a security threat.[46] When the military talks began in mid-August, negotiations quickly stalled over the topic of Soviet troop passage through Poland if the Germans attacked. British and French officials pressured Polish government to agree to the Soviet terms.[18][47] However, Polish officials bluntly refused to allow Soviet troops in Poland. They believed that once the Red Army entered Poland it might never leave.[48] The Soviets suggested that Poland's wishes be ignored, and that the tripartite agreements be concluded despite its objections.[49] The British refused to do so because they believed that such a move would push Poland into establishing stronger bilateral relations with Germany.[50]

Meanwhile, German officials secretly hinted to Soviet diplomats for months that it could offer better terms for a political agreement than Britain and France.[51] The Soviet Union began discussions with Nazi Germany regarding the establishment of an economic agreement while concurrently negotiating with those of the tripartite group.[51] In late July and early August 1939, Soviet and German officials agreed on most of the details for a planned economic agreement, and specifically addressed a potential political agreement.[52] On 19 August 1939, German and Soviet officials concluded the 1939 German–Soviet Commercial Agreement, an economic mutual understanding that exchanged Soviet Union raw materials with Germany in exchange for weapons, military technology and civilian machinery. Two days later, the Soviets suspended the tripartite military talks.[51][53] On 24 August, the Soviet Union and Germany signed the political and military deal that accompanied the trade agreement, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. This pact was an agreement of mutual non-aggression that contained secret protocols dividing the states of northern and eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence. The Soviet sphere initially included Latvia, Estonia and Finland.[Note 8] Germany and the Soviet Union would partition Poland; the areas east of the Pisa, Narev, Vistula, and San rivers going to the Soviet Union. The pact provided the Soviets with the chance of taking part in the invasion,[21] and offered an opportunity to regain territories ceded in the Peace of Riga of 1921. The Soviets would enlarge the Ukrainian and Belarusian republics to include the entire eastern half of Poland without the threat of disagreement with Adolf Hitler.[56][57]

The day after the Germans and Soviets signed the pact, the French and British military delegations urgently requested a meeting with Soviet military negotiator Kliment Voroshilov.[58] On 25 August, Voroshilov told them "[i]n view of the changed political situation, no useful purpose can be served in continuing the conversation."[58] The same day, Britain and Poland signed the British-Polish Pact of Mutual Assistance.[59] In this accord, Britain committed itself to the defence of Poland, guaranteeing to preserve Polish independence.[59]

German invasion of Poland

Hitler tried to dissuade the British and the French from interfering in the upcoming conflict and on 26 August 1939 proposed to make Wehrmacht forces available to Britain in the future.[60] At midnight on 29 August, German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop handed British Ambassador Neville Henderson the list of terms that would allegedly ensure peace in regards to Poland.[61] Under the terms, Poland was to hand over Danzig (Gdańsk) to Germany, and there was to be a plebiscite (referendum) in the Polish Corridor within the year based on residency from 1919 (not after).[61] When the Polish Ambassador Lipski went to see Ribbentrop on 30 August and said that he did not have the power to sign anything of the sort, Ribbentrop dismissed him.[62] The Germans announced that Poland had rejected German offer and negotiations with Poland were finished.[63] On 31 August, German units posing as Polish troops staged the Gleiwitz incident near the border city of Gleiwitz.[64] The following morning Hitler ordered hostilities against Poland to start at 04:45 on 1 September.[62]

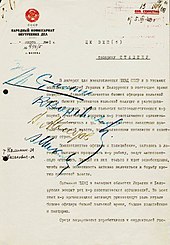

The Allied governments declared war on Germany on 3 September but failed to provide any meaningful support.[65] Despite some Polish successes in minor border battles, German technical, operational and numerical superiority forced the Polish armies to retreat from the borders towards Warsaw and Lwów. On 10 September, the Polish commander-in-chief, Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły, ordered a general retreat to the southeast towards the Romanian Bridgehead.[66] Soon after they began their invasion of Poland, the Nazi leaders began urging the Soviets to play their agreed part and attack Poland from the east. Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German ambassador to Moscow Friedrich Werner von der Schulenburg exchanged a series of diplomatic messages on the matter but the Soviets nevertheless delayed their invasion of eastern Poland. The Soviets were distracted by crucial events relating to their ongoing border disputes with Japan. They needed time to mobilize the Red Army and they saw a diplomatic advantage in waiting until Poland had disintegrated before making their move.[67][68] The undeclared war between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan at the Battles of Khalkhin Gol (Nomonhan) in the Far East ended with the Molotov–Tojo agreement between the USSR and Japan which was signed on 15 September 1939, with a ceasefire taking effect on 16 September 1939.[69] On 17 September 1939, Molotov delivered the following declaration of war to Wacław Grzybowski, the Polish Ambassador in Moscow:

Warsaw, as the capital of Poland, no longer exists. The Polish Government has disintegrated, and no longer shows any sign of life. This means that the Polish State and its Government have, in point of fact, ceased to exist. In the same way, the Agreements concluded between the U.S.S.R. and Poland have ceased to operate. Left to her own devices and bereft of leadership, Poland has become a suitable field for all manner of hazards and surprises, which may constitute a threat to the U.S.S.R. For these reasons the Soviet Government, who has hitherto been neutral, cannot any longer preserve a neutral attitude towards these facts... In these circumstances, the Soviet Government have directed the High Command of the Red Army to order troops to cross the frontier and to take under their protection the life and property of the population of Western Ukraine and Western White Russia. — People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the U.S.S.R. V. Molotov, September 17, 1939 [70]

Molotov declared on the radio that all treaties between the Soviet Union and Poland were now void; the Polish government had abandoned its people and effectively ceased to exist.[27][71] On the same day, the Red Army crossed the border into Poland.[1][67]

Soviet invasion of Poland

In the morning of 17 September 1939, Polish administration was still active on the whole territory of six eastern voivodeships, plus on parts of territories of additional five voivodeships; in eastern Poland, schools were opened in mid-September 1939.[72] Polish Army units concentrated their activities in two areas – southern (Tomaszów Lubelski, Zamość, Lwów), and central (Warsaw, Modlin, and the Bzura river). Due to stubborn Polish defense and lack of fuel, the German advance stalled, and the situation stabilized for the areas east of the line Augustów – Grodno – Białystok – Kobryń – Kowel – Żółkiew – Lwów – Żydaczów – Stryj – Turka.[73] Rail connections were operating in approximately one-third of the territory of the country, and both passenger and cargo traffic was moving on the borders with five neighboring countries (Lithuania, Latvia, Soviet Union, Romania, and Hungary). In Pińsk, assembly of PZL.37 Łoś planes was going on, in a PZL factory that had been moved from Warsaw.[74] A French Navy ship carrying Renault R35 tanks for Poland approached the Romanian port of Constanta.[75] Another ship, with artillery equipment, had just left Marseilles. Altogether, seventeen French ships with materiel were heading towards Romania, carrying fifty tanks, twenty airplanes, and large quantities of ammunition and explosives.[73] Several major cities were still in Polish hands, such as Warsaw, Lwów, Wilno, Grodno, Łuck, Tarnopol, and Lublin (captured by the Germans on 18 September). According to Leszek Moczulski, approximately 750,000 soldiers were still in the ranks of Polish Army (Polish historians Czesław Grzelak and Henryk Stańczyk claim that the Polish Army still had 650,000 soldiers,[73]) including twenty six infantry divisions and two motorized brigades. (One of the latter, the Warsaw Armoured Motorized Brigade, had not yet taken part in combat, and on 14 September began to move southwards, to join Army Kraków.)[76]

The Polish Army, although weakened by weeks of fighting, still was a formidable force. As Moczulski wrote, on 17 September 1939, the Polish Army was still bigger than most European armies and strong enough to fight the Wehrmacht for a long time.[74] On the Baranowicze – Łuniniec – Równe line, rail transport of troops from the northeastern corner of the country towards the Romanian Bridgehead was going on day and night (among them were the 35th Reserve Infantry Division under Colonel Jarosław Szafran,[77] and the so-called "Grodno Group" ("Grupa grodzieńska") of Colonel Bohdan Hulewicz), and the second largest battle of the September Campaign – Battle of Tomaszów Lubelski, started on the day of the Soviet invasion. According to Leszek Moczulski, around 250,000 Polish soldiers were fighting in central Poland, 350,000 were getting ready to defend the Romanian Bridgehead, 35,000 were north of Polesie, and 10,000 were fighting on the Baltic coast of Poland, in Hel and Gdynia. Due to the ongoing battles in the area of Warsaw, Modlin, the Bzura, Zamość, Lwów and Tomaszów Lubelski, most German divisions were ordered to move back towards these locations. The area remaining in control of the Polish authorities was some 140,000 square kilometers – approximately 200 kilometers wide and 950 kilometers long – from the Daugava to the Carpathian Mountains.[73] Polish Radio Baranowicze and Polish Radio Wilno stopped working on 16 September, after having been bombed by the Luftwaffe, but Polish Radio Lwów and Polish Radio Warsaw II still worked on 17 September.[78]

Opposing forces

The Red Army entered the eastern regions of Poland with seven field armies, containing between 450,000 and 1,000,000 troops, split between two fronts.[1] Comandarm 2nd rank Mikhail Kovalyov led the Red Army in the invasion on the Belarusian Front, while Comandarm 1st rank Semyon Timoshenko commanded the invasion on the Ukrainian Front.[1]

Under the Polish Plan West defensive plan, Poland assumed the Soviet Union would remain neutral during a conflict with Germany. As a result, Polish commanders deployed most of their troops to the west, to face the German invasion. By this time, no more than 20 under-strength battalions, consisting of about 20,000 troopers of the Border Protection Corps, defended the eastern border.[1][79] When the Red Army invaded Poland on 17 September, the Polish military was in the midst of a fighting retreat towards the Romanian Bridgehead whereupon they would regroup and await British and French relief.

Military campaign

When the Soviet Union invaded, Rydz-Śmigły was initially inclined to order the eastern border forces to resist, but was dissuaded by Prime Minister Felicjan Sławoj Składkowski and President Ignacy Mościcki.[1][79] At 04:00 on 17 September, Rydz-Śmigły ordered the Polish troops to fall back, stipulating that they only engage Soviet troops in self-defense.[1] However, the German invasion had severely damaged the Polish communication systems, causing command and control problems for the Polish forces.[80] In the resulting confusion, clashes between Polish and Soviet forces occurred along the border.[1][79] General Wilhelm Orlik-Rückemann, who took command of the Border Protection Corps on 30 August, received no official directives after his appointment.[7] As a result, he and his subordinates continued to engage Soviet forces proactively, before dissolving the group on 1 October.[7]

The Polish government refused to surrender or negotiate a peace and instead ordered all units to evacuate Poland and reorganize in France.[1] The day after the Soviet invasion started, the Polish government crossed into Romania. Polish units proceeded to manoeuvre towards the Romanian bridgehead area, sustaining German attacks on one flank and occasionally clashing with Soviet troops on the other. In the days following the evacuation order, the Germans defeated the Polish Kraków Army and Lublin Army at the Battle of Tomaszów Lubelski.[81]

Soviet units often met their German counterparts advancing from the opposite direction. Notable examples of co-operation occurred between the two armies in the field. The Wehrmacht passed the Brest Fortress to the Soviet 29th Tank Brigade, which had been seized after the Battle of Brześć Litewski on 17 September.[82] German General Heinz Guderian and Soviet Brigadier Semyon Krivoshein on 22 September held a joint parade in the town.[82] Lwów (now Lviv) surrendered on 22 September, days after the Germans had handed the siege operations over to the Soviets.[83] Soviet forces had taken Wilno (now Vilnius) on 19 September after a two-day battle, and they took Grodno on 24 September after a four-day battle. By 28 September, the Red Army had reached the line formed by the Narew, Western Bug, Vistula and San rivers—the border agreed in advance with the Germans.

Despite a tactical Polish victory on 28 September at the Battle of Szack, the outcome of the larger conflict was never in doubt.[84] Civilian volunteers, militias and reorganised retreating units held out against German forces in the Polish capital, Warsaw, until 28 September, and the Modlin Fortress, north of Warsaw, surrendered the next day after an intense sixteen-day battle. On 1 October, Soviet troops drove Polish units into the forests in the battle of Wytyczno, one of the last direct confrontations of the campaign.[85] Several isolated Polish garrisons managed to hold their positions long after being surrounded, such as those in the Volhynian Sarny Fortified Area which held out until 25 September. The last operational unit of the Polish Army to surrender was General Franciszek Kleeberg's Independent Operational Group Polesie. Kleeberg surrendered on 6 October after the four-day Battle of Kock, effectively ending the September Campaign. On 31 October, Molotov reported to the Supreme Soviet: "A short blow by the German army, and subsequently by the Red Army, was enough for nothing to be left of this bastard (ублюдок) of the Treaty of Versailles".[86][87]

Domestic reaction

The response of non-ethnic Poles to the situation added a further complication. Many Ukrainians, Belarusians and Jews welcomed the invading troops.[88] Local Communists gathered people to welcome Red Army troops in the traditional Slavic way by presenting bread and salt in the eastern suburb of Brest. For this occasion a sort of triumphal arch was made of two poles, decked with spruce branches and flowers. A banner, a long strip of red cloth with a slogan in Russian, glorifying the USSR and welcoming the Red Army, crowned the arch.[89] The local reaction was mentioned by Lev Mekhlis, who told Stalin that the people of West Ukraine welcomed the Soviets "like true liberators".[90] The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists rebelled against the Poles, and communist partisans organized local uprisings, such as that in Skidel.[1]

International reaction

The reaction of France and Britain to the Soviet invasion and annexation of Eastern Poland was muted, since neither country expected or wanted a confrontation with the Soviet Union at that time.[91][92] Under the terms of the Polish-British Common Defence Pact of 25 August 1939, the British had promised assistance if a European power attacked Poland.[Note 9] A secret protocol of the pact, however, specified that the European power referred to Germany.[94] When Polish Ambassador Edward Raczyński reminded Foreign Secretary Edward Frederick Lindley Wood of the pact, he was bluntly told that it was Britain's business whether to declare war on the Soviet Union.[91] British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain considered making a public commitment to restore the Polish state but in the end issued only general condemnations.[91] This stance represented Britain's attempt at balance: its security interests included trade with the Soviets that would support its war effort and the possibility of a future Anglo-Soviet alliance against Germany.[94] Public opinion in Britain was divided between expressions of outrage at the invasion and a perception that Soviet claims to the region were reasonable.[94]

While the French had made promises to Poland, including the provision of air support, these were not honoured. A Franco-Polish Military Alliance was signed in 1921 and amended thereafter. The agreements were not strongly supported by the French military leadership, though; the relationship deteriorated during the 1920s and 1930s.[95] In the French view, the German-Soviet alliance was fragile and overt denunciation of, or action against, the Soviets would not serve either France's or Poland's best interests.[92] Once the Soviets moved into Poland, the French and the British decided there was nothing they could do for Poland in the short term and began planning for a long-term victory instead. The French had advanced tentatively into the Saar region in early September, but after the Polish defeat they retreated behind the Maginot Line on 4 October.[96] On 1 October 1939, Winston Churchill—via the radio—stated:

... That the Russian armies should stand on this line was clearly necessary for the safety of Russia against the Nazi menace. At any rate, the line is there, and an Eastern Front has been created which Nazi Germany does not dare assail. When Herr von Ribbentrop was summoned to Moscow last week it was to learn the fact, and to accept the fact, that the Nazi designs upon the Baltic States and upon the Ukraine must come to a dead stop.[97]

Aftermath

In October 1939, Molotov reported to the Supreme Soviet that the Soviets had suffered 737 deaths and 1,862 casualties during the campaign, although Polish specialists claim up to 3,000 deaths and 8,000–10,000 wounded.[1] On the Polish side, 3,000–7,000 soldiers died fighting the Red Army, with 230,000–450,000 taken prisoner.[4] The Soviets often failed to honour the terms of surrender. In some cases, they promised Polish soldiers their freedom and then arrested them when they laid down their arms.[1]

The Soviet Union had ceased to recognise the Polish state at the start of the invasion. Neither side issued a formal declaration of war; this decision had significant consequences, and Smigly-Rydz would be criticised for it.[98] The Soviets killed tens of thousands of Polish prisoners of war, some during the campaign itself.[99] On 24 September, the Soviets killed 42 staff and patients of a Polish military hospital in the village of Grabowiec, near Zamość.[100] The Soviets also executed all the Polish officers they captured after the Battle of Szack, on 28 September 1939.[84] Over 20,000 Polish military personnel and civilians perished in the Katyn massacre.[1][82] Torture was used by the NKVD on a wide scale in various prisons, especially those in small towns.[101]

The Poles and the Soviets re-established diplomatic relations in 1941, following the Sikorski–Mayski Agreement; but the Soviets broke them off again in 1943 after the Polish government demanded an independent examination of the recently discovered Katyn burial pits.[102][103] The Soviets then lobbied the Western Allies to recognise the pro-Soviet Polish puppet government of Wanda Wasilewska in Moscow.[104][105]

On 28 September 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany signed the German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation, changing the secret terms of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. They moved Lithuania into the Soviet sphere of influence and shifted the border in Poland to the east, giving Germany more territory.[2] By this arrangement, often described as a fourth partition of Poland,[1] the Soviet Union secured almost all Polish territory east of the line of the rivers Pisa, Narew, Western Bug and San. This amounted to about 200,000 km² of land, inhabited by 13.5 million Polish citizens.[80] The border created in this agreement roughly corresponded to the Curzon Line drawn by the British in 1919, a point that would successfully be used by Stalin during negotiations with the Allies at the Teheran and Yalta Conferences.[106] The Red Army had originally sown confusion among the locals by claiming that they were arriving to save Poland from the Nazis.[107] Their advance surprised Polish communities and their leaders, who had not been advised how to respond to a Soviet invasion. Polish and Jewish citizens may at first have preferred a Soviet regime to a German one.[108] However, the Soviets were quick to impose their ideology on the local ways of life. For instance, the Soviets quickly began confiscating, nationalising and redistributing all private and state-owned Polish property.[109] During the two years following the annexation, the Soviets also arrested approximately 100,000 Polish citizens.[110] Due to a lack of access to secret Soviet archives, for many years after the war the estimates of the number of Polish citizens deported to Siberia from the areas of Eastern Poland, as well as the number who perished under Soviet rule, were largely guesswork. A wide range of numbers was given in various works, between 350,000 and 1,500,000 for the number deported to Siberia and between 250,000 and 1,000,000 for the number who died, these numbers mostly included civilians.[111] With the opening of the Soviet secret archives after 1989, the lower range of these estimates has emerged as closer to the truth. In August 2009, on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the Soviet invasion, the authoritative Polish Institute of National Remembrance announced that its researchers reduced the estimate of the number of people deported to Siberia from one million to 320,000, and estimated that 150,000 Polish citizens perished under Soviet rule during the war.[112]

Belorussia and Ukraine

Of the 13.5 million civilians living in the newly annexed territories, according to the last official Polish census the population was over 38% Poles (5.1 million), 37% Ukrainians (4.7 million), 14.5% Belarusians, 8.4% Jews, 0.9% Russians and 0.6% Germans.[113]

On 26 October, elections to Belorussian and Ukrainian assemblies were held to give the annexation an appearance of validity.[Note 10] The Belarusians and Ukrainians in Poland had been increasingly alienated by the Polonization policies of the Polish government and its repression of their separatist movements, so they felt little loyalty towards the Polish state.[10][115] Not all Belarusians and Ukrainians, however, trusted the Soviet regime.[107] In practice, the poor generally welcomed the Soviets, and the elites tended to join the opposition, despite supporting the reunification itself.[116][117] The Soviets quickly introduced Sovietization policies in Western Belorussia and Western Ukraine, including compulsory collectivization of the whole region. In the process, they ruthlessly broke up political parties and public associations and imprisoned or executed their leaders as "enemies of the people".[107] The Soviet authorities also suppressed the anti-Polish Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which had actively resisted the Polish regime since the 1920s; aiming for an independent, undivided Ukrainian state.[117][118] The unifications of 1939 were nevertheless a decisive event in the history of Ukraine and Belarus, because they produced the two republics which eventually achieved independence in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union.[119]

Communist and later censorship

Soviet censors later suppressed many details of the 1939 invasion and its aftermath.[120][121] From the start The Politburo called the operation a "liberation campaign", and later Soviet statements and publications never wavered from that line.[122] Despite the publication of a recovered copy of the secret protocols of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in the western media, for decades, it was the official policy of the Soviet Union to deny the existence of the protocols.[123] The existence of the secret protocol was officially denied until 1989. Censorship was also applied in the People's Republic of Poland, in order to preserve the image of "Polish-Soviet friendship" which was promoted by the two communist governments. Official policy only allowed accounts of the 1939 campaign that portrayed it as a reunification of the Belarusian and Ukrainian peoples and a liberation of the Polish people from "oligarchic capitalism." The authorities strongly discouraged any further study or teaching of the subject.[82][85][124] Various underground publications addressed the issue, as did other media, such as the 1982 protest song Ballada wrześniowa by Jacek Kaczmarski.[85][125]

In 2009, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin wrote in the Polish daily Gazeta Wyborcza that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact concluded in August 1939 was "immoral".[126] In 2015, then President of the Russian Federation, he commented: "In this sinse I share the opinion of our culture minister (Vladimir Medinsky) that this pact had significance for ensuring the security of the USSR".[127] In 2016 the Russian Supreme Court upheld the decision of a lower court, which had found a blogger, Vladimir Luzgin,[128] guilty of the "rehabilitation of Nazism" for reposting a text on social media that described the invasion of Poland in 1939 as a joint effort by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.[129]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Increasing numbers of Border Protection Corps units, as well as Polish Army units stationed in the East during peacetime, were sent to the Polish-German border before or during the German invasion. The Border Protection Corps forces guarding the eastern border numbered approximately 20,000 men.[1]

- ^ The retreat from the Germans disrupted and weakened Polish Army units, making estimates of their strength problematic. Sanford estimated that approximately 250,000 troops found themselves in the line of the Soviet advance and offered only sporadic resistance.[1]

- ^ The figures do not take into account the approximately 2,500 prisoners of war executed in immediate reprisals or by anti-Polish Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists.[1]

- ^ Soviet official losses – figures provided by Krivosheev – are currently estimated at 1,475 KIA or MIA presumed dead (Ukrainian Front – 972, Belorussian Front – 503), and 2,383 WIA (Ukrainian Front – 1,741, Belorussian Front – 642). The Soviets lost approximately 150 tanks in combat of which 43 as irrecoverable losses, while hundreds more suffered technical failures.[3] Sanford indicates that Polish estimates of Soviet losses are 3,000 dead and 10,000 wounded.[1] Russian historian Igor Bunich estimates Soviet losses at 5,327 KIA or MIA without a trace and WIA.[6]

- ^ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998). Poland's Holocaust. McFarland. p. 12. ISBN 0786403713.

In September, even before the start of the Nazi atrocities that would horrify the world, the Soviets began their own program of systematic individual and mass executions. On the outskirts of Lwów, several hundred policemen were executed at one time. Near Łuniniec, officers and noncommissioned officers of the Frontier Defence Cops together with some policemen, were ordered into barns, taken out and shot ... after December 1939, three hundred Polish priests were killed. And there were many other such incidents.

- ^ The exact number of people deported between 1939–1941 remains unknown. Estimates vary between 350,000 and more than 1.5 million; Rummel estimates the number at 1.2 million and Kushner and Knox 1.5 million.[14][15]

- ^ The Soviet Union was reluctant to intervene until the fall of Warsaw to the Germans.[21] The actual attack was delayed for more than a week after the decision to invade Poland was already communicated to the German ambassador Friedrich Werner von der Schulenburg on 9 September. The Soviet zone of influence according to the Pact was carved out through tactical operations.[22]

- ^ On 28 September, the borders were redefined by adding the area between the Vistula and Bug rivers to the German sphere and moving Lithuania into the Soviet sphere.[54][55]

- ^ The "Agreement of Mutual Assistance between the United Kingdom and Poland" (London, 25 August 1939) states in Article 1: "Should one of the Contracting Parties become engaged in hostilities with a European Power in consequence of aggression by the latter against that Contracting Party, the other Contracting Party will at once give the Contracting Party engaged in hostilities all the support and assistance in its power."[93]

- ^ The voters had a choice of only one candidate for each position of deputy; the communist party commissars then provided the assemblies with resolutions that would push through nationalization of banks and heavy industry and transfers of land to peasant communities.[114]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Sanford pp. 20–24

- ^ a b c "Kampania wrześniowa 1939" [September Campaign 1939]. PWN Encyklopedia (in Polish). Archived from the original on 9 May 2006. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ a b Кривошеев Г. Ф., Россия и СССР в войнах XX века: потери вооруженных сил. Статистическое исследование (Krivosheev G. F., Russia and the USSR in the wars of the 20th century: losses of the Armed Forces. A statistical survey, Greenhill 1997, ISBN 1-85367-280-7) See also: Krivosheev, Grigory Fedot (1997). Soviet casualties and combat losses in the twentieth century. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-280-7. Same.

- ^ a b c Topolewski & Polak p. 92

- ^ Zaloga, S.J., 2002, Poland 1939, Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., ISBN 9781841764085

- ^ Bunich, Igor (1994). Operatsiia Groza, Ili, Oshibka V Tretem Znake: Istoricheskaia Khronika. VITA-OBLIK. p. 88. ISBN 5-85976-003-5.

- ^ a b c Gross pp. 17–18

- ^ http://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1939pact.html

- ^ "Obozy jenieckie żołnierzy polskich" [Prison camps for Polish soldiers]. Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ a b Contributing writers (2010). "Stosunki polsko-białoruskie pod okupacją sowiecką" [Polish-Byelorussian relations under the Soviet occupation]. Internet Archive. Bialorus.pl. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bernd Wegner (1997). From peace to war: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the world, 1939–1941. Berghahn Books. p. 74. ISBN 1-57181-882-0. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Rummel p. 130

- ^ Rieber p. 30

- ^ Rummel p. 132

- ^ Kushner p.219

- ^ a b Wettig p. 47

- ^ Sylwester Fertacz, "Krojenie mapy Polski: Bolesna granica" (Carving of Poland's map). Alfa. Retrieved from the Internet Archive on 28 October 2015.

- ^ a b Watson p. 713

- ^ Watson p. 695–722

- ^ Kitchen p. 74

- ^ a b Davies (1996) p. 440

- ^ Roberts p. 74

- ^ Przemysław Wywiał (August 2011). Działania militarne w Wojnie Obronnej po 17 września [Military operations after 17 September] (PDF file, direct download). Institute of National Remembrance. pp. 70–78. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "The German Ambassador in the Soviet Union, (Schulenburg) to the German Foreign Office No. 317". Avalon project. Lillian Goldman Law Library. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ "The German Ambassador in the Soviet Union, (Schulenburg) to the German Foreign Office No. 371". Avalon project. Lillian Goldman Law Library. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ "The German Ambassador in the Soviet Union, (Schulenburg) to the German Foreign Office No. 372". Avalon project. Lillian Goldman Law Library. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ a b Degras pp. 37–45

- ^ Roshwald p. 37

- ^ Davies (1972) p. 29

- ^ Davies (2002) p. 22, 504

- ^ Kutrzeba pp. 524, 528

- ^ Davies (2002) p. 376

- ^ Davies (2002) p. 504

- ^ Davies (1972) p. xi

- ^ Lukowski, Jerzy; Zawadzki, Hubert (2001). A Concise History of Poland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 0-521-55917-0.

- ^ Gross p. 3

- ^ Watson p. 698

- ^ Gronowicz p. 51

- ^ Neilson p. 275

- ^ Carley 303–341

- ^ Kenéz pp. 129–131

- ^ Robert C. Grogin (2001). Natural Enemies: The United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War, 1917–1991. Lexington Books. p. 28. ISBN 0739101609.

- ^ Watson p. 695

- ^ Shaw p. 119

- ^ Neilson p. 298

- ^ Watson p. 708

- ^ Shirer p. 536

- ^ Shirer p. 537

- ^ Neilson p. 315

- ^ Neilson p. 311

- ^ a b c Roberts pp. 66–73

- ^ Shirer p. 503

- ^ Shirer p. 525

- ^ Sanford p. 21

- ^ Weinberg p. 963

- ^ Dunnigan p. 132

- ^ Snyder p. 77

- ^ a b Shirer pp. 541–2

- ^ a b Osmańczyk-Mango p. 231

- ^ "Telegram: His Majesty's Ambassador in Berlin – Dept of State 8/25/39". Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ a b Davies (2002) p. 371–373

- ^ a b Mowat p. 648

- ^ Henderson pp. 16–18

- ^ Manvell-Fraenkel p. 76

- ^ Mowat p. 648–650

- ^ Stanley p. 29

- ^ a b Zaloga p. 80

- ^ Weinberg p. 55

- ^ Goldman p. 163, 164

- ^ Electronic Museum, Text of the Soviet communique in English translation. September 17, 1939, by Vyacheslav M. Molotov.

- ^ Piotrowski p. 295

- ^ Zachód okazał się parszywieńki. Interview with Leszek Moczulski, 28-08-2009

- ^ a b c d Czesław Grzelak, Henryk Stańczyk. Kampania polska 1939 roku, page 242. RYTM Warszawa 2005. ISBN 83-7399-169-7

- ^ a b Leszek Moczulski, Wojna Polska 1939, page 879. Bellona Warszawa 2009. ISBN 978-83-11-11584-2

- ^ Encyklopedia Broni (Encyclopedia of Weapons), Renault R-35, R-40, czołg lekki II wojna światowa 1939–1945, → wozy bojowe, Francja

- ^ Tomaszów Lubelski. Bitwa w dniach 17–20.IX.1939 (bitwa pod Tomaszowem Lubelskim 1939), portal www.1939.pl

- ^ Artur Leinwand, OBRONA LWOWA WE WRZEŚNIU 1939 ROKU

- ^ [Janusz Osica, Andrzej Sowa, and Paweł Wieczorkiewicz. 1939. Ostatni rok pokoju, pierwszy rok wojny. Wydawnictwo Zysk i S-ka, Poznań 2009, page 569]

- ^ a b c Topolewski & Polak p. 90

- ^ a b Gross p. 17

- ^ Taylor p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Fischer, Benjamin B. (Winter 1999–2000). "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field". Studies in Intelligence. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ Artur Leinwand (1991). "Obrona Lwowa we wrześniu 1939 roku". Instytut Lwowski. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ a b "Szack". Encyklopedia Interia (in Polish). Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ a b c Orlik-Rückemann p. 20

- ^ Moynihan p. 93

- ^ Tucker p. 612

- ^ Gross pp. 32–33

- ^ Юрий Рубашевский. (16 September 2011). Радость была всеобщая и триумфальная (in Russian). Vecherniy Brest.

- ^ Montefiore p 312

- ^ a b c Prazmowska pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b Hiden & Lane p. 148

- ^ Stachura p. 125

- ^ a b c Hiden & Lane pp. 143–144

- ^ Hehn pp. 69–70

- ^ Jackson p. 75

- ^ Winston S. Churchill, Blood, Sweat and Tears. "The First Month of War." P. 173.

- ^ Sanford pp. 22–23, 39

- ^ Sanford p. 23

- ^ "Rozstrzelany Szpital" [Executed Hospital] (pdf) (in Polish). Tygodnik Zamojski. 15 September 2004. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ Gross p. 182

- ^ "Soviet Note of April 25, 1943". 25 April 1943. Archived from the original on 9 September 2005. Retrieved 19 December 2005.

- ^ Sanford p. 129

- ^ Sanford p. 127

- ^ Dean p. 144

- ^ Dallas p. 557

- ^ a b c Davies (1996) pp. 1001–1003

- ^ Gross pp. 24, 32–33

- ^ Piotrowski p. 11

- ^ "Represje 1939–41 Aresztowani na Kresach Wschodnich" [Repressions 1939–41. Arrested on the Eastern Borderlands.]. Ośrodek Karta (in Polish). Archived from the original on 21 October 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ Rieber pp. 14, 32–37

- ^ "Polish experts lower nation's WWII death toll". AFP/Expatica. 30 July 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Trela-Mazur p. 294

- ^ Rieber pp. 29–30

- ^ Davies (2002) pp 512–513.

- ^ Wierzbicki, Marek (2003). "Stosunki polsko-białoruskie pod okupacją sowiecką (1939–1941)". Białoruskie Zeszyty Historyczne (in Polish) (20). Biełaruski histaryczny zbornik: 186–188. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ a b Nowak (online)

- ^ Miner p. 41-42

- ^ Wilson p. 17

- ^ Kubik p. 277

- ^ Sanford pp. 214–216

- ^ Rieber p. 29

- ^ Biskupski & Wandycz p. 147

- ^ Ferro p. 258

- ^ Kaczmarski, Jacek. "Ballada wrześniowa" [September's tale] (in Polish). Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ Kuhrt, Natasha (2014). Russia and the World: The Internal-External Nexus. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 1317850378.

- ^ "Putin defends notorious Nazi-Soviet pact". Yahoo News. 10 May 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ "How Russia is engaged in a battle for its own history". Sky News. 11 December 2016.

- ^ Anna, Azarova (2 September 2016). "Russia's Supreme Court Questions USSR's Role in 1939 Invasion of Poland". Retrieved 3 September 2016.

Bibliography

- Biskupski, Mieczyslaw B.; Wandycz, Piotr Stefan (2003). Ideology, Politics, and Diplomacy in East Central Europe. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 1-58046-137-9.

- Carley, Michael Jabara (1993). "End of the 'Low, Dishonest Decade': Failure of the Anglo–Franco–Soviet Alliance in 1939". Europe-Asia Studies. 45 (2): 303–341. doi:10.1080/09668139308412091.

- Dallas, Gregor (2005). 1945: The War That Never Ended. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10980-1.

- Davies, Norman (1972). White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–20. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-7126-0694-7.

- Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820171-0.

- Davies, Norman (2002). God's Playground (revised ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12819-3.

- Dean, Martin (2000). Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941–44. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6371-1.

- Degras, Jane Tabrisky (1953). Soviet Documents on Foreign Policy. Volume I: 1917–1941. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dunnigan, James F. (2004). The World War II Bookshelf: Fifty Must-Read Books. New York: Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-2609-2.

- Ferro, Marc (2003). The Use and Abuse of History: Or How the Past Is Taught to Children. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-28592-6.

- Fraser, Thomas Grant; Dunn, Seamus; von Habsburg, Otto (1996). Europe and Ethnicity: the First World War and contemporary ethnic conflict. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11995-2.

- Goldstein. Missing.

- Gelven, Michael (1994). War and Existence: A Philosophical Inquiry. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01054-1.

- Goldman, Stuart D. (2012). Nomonhan, 1939; The Red Army's Victory That Shaped World War II. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-098-9.

- Gronowicz, Antoni (1976). Polish Profiles: The Land, the People, and Their History. Westport, CT: L. Hill. ISBN 0-88208-060-1.

- Gross, Jan Tomasz (2002). Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09603-1.

- Hehn, Paul N. (2005). A low dishonest decade: the great powers, Eastern Europe, and the economic origins of World War II, 1930–1941. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1761-9.

- Henderson (1939). Documents concerning German-Polish relations and the outbreak of hostilities between Great Britain and Germany on September 3, 1939. Great Britain Foreign Office.

- Hiden, John; Lane, Thomas (2003). The Baltic and the Outbreak of the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53120-7.

- House, Edward; Seymour, Charles (1921). What Really Happened at Paris. Scribner.

- Jackson, Julian (2003). The Fall of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280300-X.

- Kenéz, Peter (2006). A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86437-4.

- Kitchen, Martin (1990). A World in Flames: A Short History of the Second World War. Longman. ISBN 0-582-03408-6.

- Kubik, Jan (1994). The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: the Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01084-3.

- Kushner, Tony; Knox, Katharine (1999). Refugees in an Age of Genocide. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4783-7.

- Kutrzeba, S (1950). "The Struggle for the Frontiers, 1919–1923". In Reddaway, William Fiddian (ed.). The Cambridge history of Poland |volume1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 512–543.

- Levin, Dov (1995). The lesser of two evils: Eastern European Jewry under Soviet rule, 1939–1941. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0-8276-0518-3.

- Manvell, Roger; Fraenkel, Heinrich (2007). Heinrich Himmler: The Sinister Life of the Head of the SS and Gestapo. London: Greenhill. ISBN 978-1-60239-178-9.

- Mendelsohn, Ezra (2009). Jews and the Sporting Life: Studies in Contemporary Jewry XXIII. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538291-4.

- Miner, Steven Merritt (2003). Stalin's Holy War: Religion, Nationalism, and Alliance Politics, 1941–1945. North Carolina: UNC Press. ISBN 0-8078-2736-3.

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2003). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 1-4000-7678-1.

- Mowat, Charles Loch (1968). Britain between the wars: 1918–1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-416-29510-X.

- Moynihan, Daniel Patrick (1990). On the Law of Nations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63575-2.

- Neilson, Keith (2006). Britain, Soviet Russia and the Collapse of the Versailles Order, 1919–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85713-0.

- Nowak, Andrzej (January 1997). "The Russo-Polish Historical Confrontation". Sarmatian Review. XVII (1). Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- Orlik-Rückemann, Wilhelm (1985). Jerzewski, Leopold (ed.). Kampania wrześniowa na Polesiu i Wołyniu: 17.IX.1939–1.X.1939 (in Polish). Warsaw: Głos.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1998). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife: Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

- Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003). Mango, Anthony (ed.). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and international agreements. Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93921-6.

- Polonsky, Antony; Michlic, Joanna B. (2004). The neighbors respond: the controversy over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11306-7.

- Prazmowska, Anita J. (1995). Britain and Poland 1939–1943: The Betrayed Ally. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48385-9.

- Rieber, Alfred Joseph (2000). Forced Migration in Central and Eastern Europe: 1939–1950. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5132-X.

- Roberts, Geoffrey (1992). "The Soviet Decision for a Pact with Nazi Germany". Soviet Studies. 44 (1): 57–78. doi:10.1080/09668139208411994.

- Roshwald, Aviel (2001). Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires: Central Europe, the Middle East and Russia, 1914–1923. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17893-2.

- Rummel, Rudolph Joseph (1990). Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917. New Jersey: Transaction. ISBN 1-56000-887-3.

- Ryziński, Kazimierz; Dalecki, Ryszard (1990). Obrona Lwowa w roku 1939 (in Polish). Warszawa: Instytut Lwowski. ISBN 978-83-03-03356-7.

- Sanford, George (2005). Katyn and the Soviet Massacre Of 1940: Truth, Justice And Memory. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-33873-5.

- Shaw, Louise Grace (2003). The British Political Elite and the Soviet Union, 1937–1939. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5398-5.

- Shirer, William L. (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-72868-7.

- Snyder, Timothy (2005). "Covert Polish Missions Across the Soviet Ukrainian Border, 1928–1933". In Salvatici, Silvia (ed.). Confini: Costruzioni, Attraversamenti, Rappresentazionicura. Soveria Mannelli (Catanzaro): Rubbettino. ISBN 88-498-1276-0.

- Stachura, Peter D. (2004). Poland, 1918–1945: An Interpretive and Documentary History of the Second Republic. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-34357-7.

- Stanley. Missing.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1975). The Second World War: An Illustrated History. London: Putnam. ISBN 0-399-11412-2.

- Topolewski, Stanisław; Polak, Andrzej (2005). 60. rocznica zakończenia II wojny światowej [60th anniversary of the end of World War II] (PDF). Edukacja Humanistyczna w Wojsku (Humanist Education in the Army) (in Polish). Vol. 1. Dom wydawniczy Wojska Polskiego (Publishing House of the Polish Army). ISSN 1734-6584. Archived from the original (pdf) on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Trela-Mazur, Elżbieta (1997). Bonusiak, Włodzimierz (ed.). Sowietyzacja oświaty w Małopolsce Wschodniej pod radziecką okupacją 1939–1941 (in Polish). Kielce: Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna im. Jana Kochanowskiego. ISBN 978-83-7133-100-8 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Tucker, Robert C. (1992). Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1929–1941. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-30869-3.

- Watson, Derek (2000). "Molotov's Apprenticeship in Foreign Policy: The Triple Alliance Negotiations in 1939". Europe-Asia Studies. 52 (4): 695–722. doi:10.1080/713663077.

- Weinberg, Gerhard (1994). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44317-2.

- Wilson, Andrew (1997). Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57457-9.

- Wettig, Gerhard (2008). Stalin and the Cold War in Europe: the emergence and development of East–West conflict, 1939–1953. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-5542-9.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (2002). Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-408-6.