Wikipedia:Reference desk/Language

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

June 6

Etymology of moin moin

Apparently moin moin is a Nigerian dish. However, "moin moin" is literally used as a greeting in some German dialects. What is the etymology of moin moin (the dish)? Does it come from the greeting? And if so, why? JIP | Talk 08:45, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- Here's someone claiming it's of Yoruba origin (which seems otherwise credible). Here's an old English-Yoruba dictionary. Personuser (talk) 09:53, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- This may be a folk etymology, but many people who use "moin moin" as a greeting claim it come from the same root as "morning"; the etymology section of that article has more details and controversy, but that seems the most likely origin. Certainly "Morgen", short for "Guten Morgen" is a common casual greeting in Germany, along with assorted dialect variants. The spelling of the Nigerian term may be the same, but I'd suspect the pronunciation would be different. The Europeans grabbing stuff in Nigeria were also mostly Portuguese and Brits, not generally Germans, though admittedly northern Germany has always produced sailors, who went (and go) everywhere on ships under assorted flags. HLHJ (talk) 13:32, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- The name for the dish is mentioned as a loanword of Yoruba origin in some more reliable sources [1][2], they don't give a more detailed etymology and this wouldn't rule out a "double borrowing" (which would be even less probable, at least for a German origin). Alternative spellings/names include "mai mai", "moyin moyin", "moyen moyen",... (these can be very misleading without some more context). It is a quite popular dish and seems to bring up local rivalities, which would make folk etymologies even more likely. An example would be mo eyin "stick to teeth" (the link I found is blacklisted, so this should probably be taken with even more caution, I couldn't find anything similar in reliable sources). For the greeting there is a long, but not so helpful discussion at [3]. The German article may have some more details and additional sources, for those who can read them. Personuser (talk) 22:16, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- How do you pronounce the greeting? Temerarius (talk) 22:53, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- I don't speak German natively, but I have learned it to a very good degree. As far as I understand, the greeting "moin moin" is pretty much literally pronounced as it is written, as is the case in most (but not nearly all) words in German. As far as I understand, "moin" is pronounced to rhyme with "loin" in English (discounting for minor variations in the vowels). JIP | Talk 00:18, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- Wiktionary:moin has some IPA transcriptions and an audio sample (keep in mind that the page includes unrelated words in other languages, and probably doesn't cover all the local variations and related or possibly related expressions in other languages, specially for such a common/colloquial word, left alone how the word was pronounced by nord German sailors more that one century ago or similar, which seems to be, using an euphemism, "challenging" to determine even for worlds with a clearer etymology). Personuser (talk) 00:58, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- I don't speak German natively, but I have learned it to a very good degree. As far as I understand, the greeting "moin moin" is pretty much literally pronounced as it is written, as is the case in most (but not nearly all) words in German. As far as I understand, "moin" is pronounced to rhyme with "loin" in English (discounting for minor variations in the vowels). JIP | Talk 00:18, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- How do you pronounce the greeting? Temerarius (talk) 22:53, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- The name for the dish is mentioned as a loanword of Yoruba origin in some more reliable sources [1][2], they don't give a more detailed etymology and this wouldn't rule out a "double borrowing" (which would be even less probable, at least for a German origin). Alternative spellings/names include "mai mai", "moyin moyin", "moyen moyen",... (these can be very misleading without some more context). It is a quite popular dish and seems to bring up local rivalities, which would make folk etymologies even more likely. An example would be mo eyin "stick to teeth" (the link I found is blacklisted, so this should probably be taken with even more caution, I couldn't find anything similar in reliable sources). For the greeting there is a long, but not so helpful discussion at [3]. The German article may have some more details and additional sources, for those who can read them. Personuser (talk) 22:16, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- This may be a folk etymology, but many people who use "moin moin" as a greeting claim it come from the same root as "morning"; the etymology section of that article has more details and controversy, but that seems the most likely origin. Certainly "Morgen", short for "Guten Morgen" is a common casual greeting in Germany, along with assorted dialect variants. The spelling of the Nigerian term may be the same, but I'd suspect the pronunciation would be different. The Europeans grabbing stuff in Nigeria were also mostly Portuguese and Brits, not generally Germans, though admittedly northern Germany has always produced sailors, who went (and go) everywhere on ships under assorted flags. HLHJ (talk) 13:32, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

Make no mistake about it

I'm under impression that "Make no mistake about it" is used most frequently in American English, being a favorite phrase among US officials more than anywhere else. Is the phrase indeed more popular in the US? 212.180.235.46 (talk) 20:54, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- BrEng speaker here. The phrase is in common use in the UK, but normally just as "make no mistake", i.e. without the "about it". --Viennese Waltz 21:11, 6 June 2021 (UTC)

- I think its common use among politicians is similar to "let's be clear": it always prefaces a huge lie that they want to perpetrate on the media and the people. Elizium23 (talk) 11:49, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- According to the Corpus of Global Web-Based English, "make no mistake" appears 1289 times in US sources and 921 times in GB sources, while "make no mistake about it" appears 226 times in US sources and 119 times in GB sources. The total number of words from the two countries is similar (386,809,355 from US and 387,615,074 from GB). CodeTalker (talk) 19:01, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- Apparently Nixon liked to use it (see this thread at Stack Exchange, also tracing it back to 18th century James Ussher in a technichally non-imperative (though subjunctive) form, and to 19th century John Poole (in its imperative form, though I actually think that example could also be about advising someone not to mess up a future action he is to perform). ---Sluzzelin talk 19:36, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

June 7

What does "my not so" mean?

In Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2, Dumbledore says to Harry Potter:

Dumbledore: I've always prized myself on my ability to turn a phrase. Words are, in my not so humble opinion...our most inexhaustible source of magic...capable of both inflicting injury and remedying it.

What does "my not so" mean? Rizosome (talk) 07:12, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- It is in two parts, "my" and "not so". Dumbledore has an opinion, which he thinks is not so humble. JIP | Talk 07:15, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- Some writers (or style guides) would hyphenate this, as "my not-so-humble opinion", which makes the sense clearer. It's an example of a compound modifier. AndrewWTaylor (talk) 09:10, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- See also in my humble opinion. Alansplodge (talk) 11:14, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- ... which has the initialism IMHO. The Urban Dictionary even claims there's one that's not so humble - IMNSHO - though I've never seen it used. Clarityfiend (talk) 11:20, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- I have seen IMNSHO used. --Khajidha (talk) 11:42, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- I have seen both IMHO and IMNSHO used quite a lot. JIP | Talk 12:42, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- My recollection from the 90s is that IMHO was most prevalent, with IMO being a minority player. IMNSHO was an obviously humorous extension. Matt Deres (talk) 18:56, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- Fanspeak is full of examples of IMAO ("in my arrogant opinion") counterposed to IMHO, both in fanzines and (nowadays) online. --Orange Mike | Talk 02:14, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- My recollection from the 90s is that IMHO was most prevalent, with IMO being a minority player. IMNSHO was an obviously humorous extension. Matt Deres (talk) 18:56, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- I have seen both IMHO and IMNSHO used quite a lot. JIP | Talk 12:42, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- I have seen IMNSHO used. --Khajidha (talk) 11:42, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- ... which has the initialism IMHO. The Urban Dictionary even claims there's one that's not so humble - IMNSHO - though I've never seen it used. Clarityfiend (talk) 11:20, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- See also in my humble opinion. Alansplodge (talk) 11:14, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

Pluralised groups in Irish English

Does Irish English follow the British English pattern of pluralizing groups: such as "the clan were living in Dublin" vs. "the clan was living in Dublin"? Are there exceptions to this rule where the verb might sometimes be singular instead? Elizium23 (talk) 12:03, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- I don't know about Irish English specifically, but both British English and American English have both "formal agreement" and "notional agreement" -- they just distribute them a little differently. The Wikipedia article is Synesis (a word which I'm not sure I've ever heard before, and which I doubt is in common use among linguists). AnonMoos (talk) 14:20, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- Pancake sentence points to Zeugma and syllepsis- --Error (talk) 00:03, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- "Irish English's writing standards align with British rather than American English" according to our Hiberno-English article. Alansplodge (talk) 11:08, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

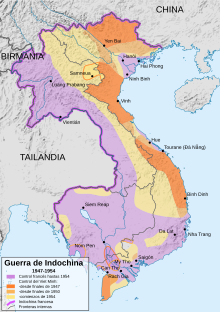

Can someone here please translate the legend in this map from Spanish to English?

Here is the map itself:

68.228.73.154 (talk) 19:42, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- "French control until 1954"

- "Viet Minh control:"

- "

throughsince late 1947" - "

throughsince late 1950" - "beginning in 1954"

- "French Indochina"

- "Internal borders" Elizium23 (talk) 19:46, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- Is the translation for the map legend the exact same for the German version of this map?

- Yes, pretty much so. JIP | Talk 21:51, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- An independent translation of the German:

- under French control until 1954

- under the control of the Viet Minh

- –since the end of 1947

- –since the end of 1950

- –beginning of 1954

- French Indochina

- Borders within Indochina

- I think the Spanish lines 3 & 4 also mean "since the end of 1947|1950". And where the Spanish legend has "1947–1954", the German is more verbose: "Course from 1947 to 1954". --Lambiam 22:09, 7 June 2021 (UTC)

- Correct. "Since late 1947" and "since late 1950", as well as "since early 1954." I'm a native Spanish speaker. Moony483 (talk) 18:19, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- An independent translation of the German:

June 8

ΗΑΓΙΑ ΕΥΔΟΚΗΑ

The attached Byzantine stonecraft represents Aelia Eudocia, saint and empress. What peeves me is the Greek spelling of her name in the mosaic. I don't really know Greek, but I read it as ΗΑΓΙΑ ΕΥΔΟΚΗΑ. However it seems very irregular to me as Η is representing both /h/ and /i/ in the same phrase. Is that normal and I am missing basic notions of Greek alphabet? Is it a transitional spelling? Is it because Eudocia was both a Christian saint and a Homeric erudite? --Error (talk) 00:18, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- The first Η, could be the article, the latin H in the file name would represent the Rough breathing, which isn't marked in the mosaic. I'm not that familiar with Greek from that period or the use of articles to be sure. This mosaic seems to confirm my suspects, not sure of its dating, but icons weres probably quite conservative. Personuser (talk) 01:01, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- Saint Panteleimon, Nicosia was started in 1993, if I understand the Google translation of bg:Свети Пантелеймон (Никозия). (It makes me wonder whether the mosaic is allowed to be in Commmons.)

- I didn't know of it as an article (wikt:Η). It makes sense, though.

- --Error (talk) 08:22, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- I guess the self proclaimed copyright owner is the one who took the picture, not sure how this works for mosaics. Your dating is some centuries more accurate than my supposition (at least the infobox is pretty clear to me) and it seems I managed to choose probably the worst possible image for comparision; the explanation is otherwise more solid the more I look at it ("the Saint Eudocia", in English you wouldn't use the article, but seems used even in modern Greek). Personuser (talk) 09:08, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- A couple of letters are paired. Does that indicate a diphthong? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 09:58, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- I don't think so. ΓΙ becomes /j/, ΕΥ becomes (in this context) /ev/, and ΗΑ is /ia/.

- Another example is this icon of Saint Philothei of Athens. This use of the definite article is perfectly common in Greek. For a male saint the article is (in Ancient Greek) ὁ, as a capital letter without spiritus Ο, as seen (with spiritus) on icons for the saints Eutychius and Leonidas. The file on Wikimedia Commons should be renamed to "Agia Eudokia.jpg". --Lambiam 10:16, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- So it is an article. Thanks everybody. --Error (talk) 10:53, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- A couple of letters are paired. Does that indicate a diphthong? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 09:58, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- I guess the self proclaimed copyright owner is the one who took the picture, not sure how this works for mosaics. Your dating is some centuries more accurate than my supposition (at least the infobox is pretty clear to me) and it seems I managed to choose probably the worst possible image for comparision; the explanation is otherwise more solid the more I look at it ("the Saint Eudocia", in English you wouldn't use the article, but seems used even in modern Greek). Personuser (talk) 09:08, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

What's missing phrase after "I am"?

In Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2, Harry speaks to his son:

Harry: Albus Severus Potter...you were named after two headmasters of Hogwarts. One of them was Slytherin... and he was the bravest man I've ever known.

Albus: But just say that I am.

Harry: Then Slytherin House will have gained a wonderful young wizard. But, listen, if it really means that much to you, you can choose Gryffindor.

What's missing phrase after "I am"? Rizosome (talk) 11:36, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- I haven't read the book, but from context it appears that Albus is saying "But just say that I am the bravest man you've ever known". This follows logically from Harry's line. I could be wrong though. JIP | Talk 12:06, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- Albus was actually wondering what will happen if he's selected to go to Slytherin House, because it still has a bad reputation, so he's really asking "but what if I am put in Slytherin" despite what Harry said about Slytherins. (Personally I think if a magic hat sorts out all of the evil people for you, it seems like it would be easy to immediately solve all their problems, but oh well.) Adam Bishop (talk) 12:21, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- Adam Bishop, I think the concept of good vs. evil and Slytherin vs. Gryffindor is far more nuanced than you give it credit for. Perhaps Slytherin has a "bad reputation" among some... but the sorting hat certainly isn't "sorting out all of the evil people". That's not the point of the four Houses. Elizium23 (talk) 14:25, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- They should execute everyone sorted into Slytherin, just to be safe. Adam Bishop (talk) 14:40, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- Adam Bishop, I think the concept of good vs. evil and Slytherin vs. Gryffindor is far more nuanced than you give it credit for. Perhaps Slytherin has a "bad reputation" among some... but the sorting hat certainly isn't "sorting out all of the evil people". That's not the point of the four Houses. Elizium23 (talk) 14:25, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- Agree with Adam Bishop. This is made clear by what Harry says next: "Slytherin House will have gained a wonderful young wizard" if Albus is sorted into it. --Khajidha (talk) 14:16, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- In fact, this snippet of dialogue is immediately preceded by young Albus, about to take the Hogwarts Express for the first time, anxiously questioning: "Dad, what if I am put in Slytherin?". Decades earlier, the Sorting Hat had been inclined to sort Harry into Slytherin, but was swayed by his ardent wish to be put in Gryffindor. --Lambiam 18:49, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- Albus was actually wondering what will happen if he's selected to go to Slytherin House, because it still has a bad reputation, so he's really asking "but what if I am put in Slytherin" despite what Harry said about Slytherins. (Personally I think if a magic hat sorts out all of the evil people for you, it seems like it would be easy to immediately solve all their problems, but oh well.) Adam Bishop (talk) 12:21, 8 June 2021 (UTC)

- It appears I was completely wrong. As I said, I hadn't read the book, so the only context I had was what was written in this question. JIP | Talk 09:37, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

June 9

It's all Greek to me

Hi all, I was randomly reading Rhodes#Hellenistic age, where this sentence occurs:

- To this end they employed as leverage their economy and their excellent navy, which was manned by proverbially the finest sailors in the Mediterranean world: "If we have ten Rhodians, we have ten ships."[citation needed]

I have tracked this down to Pseudo-Diogenian, Ancient Greek: Ημέίς δέχα Ρόδιοι, δέχα νηές: επι τον αλαζονευομένον, in

- von Leutsch, E. L.; Schneidewin, F. G. (1839). Corpus paroemiographorum Graecorum, Vol. I. 'Diogeniani', Century V, 18 (in Ancient Greek and Latin). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 254.

Could someone please check my transcription for mistakes, and possibly make a literal translation? Cheers, >MinorProphet (talk) 03:50, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- There are some flaws (χ/κ and diacritics), this is my attempt (based only on the linked edition): Ancient Greek: Ἡμεῖς δέκα Ῥόδιοι, δέκα νῆες: ἐπὶ τῶν ἀλαζονευομένων. A painfully litteral translation would be "To us ten Rodians, ten ships: by those who brag." I would still wait for a second opinion. It would also make sense to better check if there is a less fragmented source for this phrase. By the way, does anybody know of a relatively painless way to type Greek diacritics (I can switch to modern Greek keyboard, but that doesn't seem to help a lot)? Personuser (talk) 05:24, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- Just below the wikitext edit window there is a dropdown menu with choices Insert / Wiki markup / Symbols / Latin / Greek / ... After selecting Greek, this section expands to a Greek smorgasbord menu, and you can insert ᾧ or whatever diacritically challenged letter with just a single point and click. --Lambiam 11:29, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- Thanks for the hint and the correction (I guess my Greek is more rusty than I thought). I also realized only later that the second part was the title/source. Personuser (talk) 14:56, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- Just below the wikitext edit window there is a dropdown menu with choices Insert / Wiki markup / Symbols / Latin / Greek / ... After selecting Greek, this section expands to a Greek smorgasbord menu, and you can insert ᾧ or whatever diacritically challenged letter with just a single point and click. --Lambiam 11:29, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- Ἡμεῖς is in the nominative case: "We [are] ten Rhodians, [we are] ten ships". --Lambiam 11:43, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- There are some flaws (χ/κ and diacritics), this is my attempt (based only on the linked edition): Ancient Greek: Ἡμεῖς δέκα Ῥόδιοι, δέκα νῆες: ἐπὶ τῶν ἀλαζονευομένων. A painfully litteral translation would be "To us ten Rodians, ten ships: by those who brag." I would still wait for a second opinion. It would also make sense to better check if there is a less fragmented source for this phrase. By the way, does anybody know of a relatively painless way to type Greek diacritics (I can switch to modern Greek keyboard, but that doesn't seem to help a lot)? Personuser (talk) 05:24, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- Thanks very much for your helpful and learned replies. In addition, there are a number of refs in the notes on p. 254, which appear to confirm the quote and the Rhodians' nautical ability etc.: but I can't identify the second and third. Would anyone be able to help, please, just for my curiosity?

- Apost. IX, 85.[1] Arsen. 276. Adagium ex Hom. il. II, 653 sq. natum esse male cum Erasmo Schottus[2] opinatur: ex Rhodiorum ingenio repetendum potius videtur: v. O. Muelleri Dorr. II, 413: adde, quod Rhodi machinarum bellicarum et armorium artificium egregie exercebatur: Diod. XX, 84. Strab. XIV, 2, 5 p. 65. Meursius de Rhodo I, c. 17 Opp. Omn. T. III, 725: succurrit denique explicationi nostrae aliud dictum proverbiale, quod a Rhodio gubernatore, ut narratur, exiit: etc. MinorProphet (talk) 14:38, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- Thanks very much for your helpful and learned replies. In addition, there are a number of refs in the notes on p. 254, which appear to confirm the quote and the Rhodians' nautical ability etc.: but I can't identify the second and third. Would anyone be able to help, please, just for my curiosity?

References

- ^ p. 116 [pdf 124]: Nos decem Rhodii, decem naves. De iactubundis. (ie a boast).

- ^ (?) Schottus, Andrea, S. J., Adagia sive proverbia graecorum ex Zenobio seu Zenodoto, Diogeniano et Suidae collectaneis. Partim edita nunc primum partim latine reddita, scholiisque parallelis illustrata, Antwerp: Plantin 1612

Colonial fort quote

Does the following quote by former Mogadishu governor Caroselli say that the colonial era forts undermentioned are Dhulbahante forts: "i Dulbohanta nella maggior parte si sono arresi agli inglesi c han loro consegnato ventisette garese case ricolme di fucili, munizioni e danaro" ? Heesxiisolehh (talk) 11:26, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- This is a quote from his book Ferro e Fuoco in Somalia. I did not find an accessible version, but it seems that there are typos in the Italian text. I think c han should be c'han, and I have no idea what garese are; perhaps a local name for a (type of?) house. There is an Italian word garrese, but that does not make sense in the context. The quote says that the Dulbohanta (people) for the larger part have surrendered and have handed over twenty-seven garese houses. It does not refer to forts, unless the garese are fortified houses. "Garisa" is the name of a village in Somaliland. --Lambiam 12:36, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- "garesa" (plural "garese") must be a type of fortification in that region, see Treccani's search links for "garesa" and "garese". ---Sluzzelin talk 12:44, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- That strange "c" is really a defective "e", meaning "and" in English. "Garese" is indeed the plural of "garesa", meaning "fort". The "garese case" part doesn't sound quite right in Italian. It would make sense if it was: "han loro consegnato ventisette garese, case ricolme di fucili, munizioni e danaro" = They have handed out to them twentyseven 'garese', houses full of rifles, ammunitions and money". Or even if it was "case-garese" = "houses-forts". Here you can see the text in Google Books: https://books.google.it/books?newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&id=n2wMAQAAIAAJ&dq=arresi+agli+inglesi+c+han+loro+consegnato+ventisette+garese&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=%22ventisette+garese%22 --95.246.53.249 (talk) 14:54, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- So if per @Sluzzelin: "garese" is the plural of "garesa" meaning fort, the full translation would become both house and fort, as in "house-fort", as follows: "the Dhulbahante have handed out to them twenty seven 'house-forts' full of rifles, ammunitions and money", correct? Heesxiisolehh (talk) 16:50, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- The text linked by the IP has some other oddities ("garese case) ricolme" and later "armti" instead of "armati"). I think the most probable meaning is either "forts, houses,etc..." or the house part clarifying what is a garesa ("forts (houses full of guns...)"). "Garesa" is described as a "forte" or even "castello" in Treccani (not quite a house), so I would propend for the first one. Garese being the plural of garesa and "c" being "e" is otherwise quite clear. If the money and ammunitions are different items in the list or something the houses were full of is also somewhat ambiguos due to the odd puctuation.Personuser (talk) 17:55, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- There may be an opening parenthesis missing; perhaps the text was ... garese (case) ricolme di .... --Lambiam 20:07, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- I found a pdf of the cited book by Caroselli. It states they got permission from Naples University L'Orientale, which arguably may have better copyright practices than Google, anyway should be good for checking translations. Page 272 (as reported by Sayid Maxamed Cabdulle Xasan?), in the end part. Here's my reading: "i Dulbohanta nella maggior parte si sono arresi agli inglesi e han loro consegnato ventisette garese (case) ricolme di fucili, munizioni e danaro". So: "... handed out to them twentyseven 'garesas' (houses) full of rifles, ammunitions and money". "Garesa" seems a pretty specific/unusual term even in Italian; they seem to have a defensive purpose (and probably a local/Somalian connotation), but translating them directly as "forts" may not be the best choise. It seems Lambiam was right, I missed the comment before answering, probably there's also some OCR going on. This way is also clear the money was in the garese/garesas (not sure what's more appropriate in English) and not an additional item. Personuser (talk) 21:07, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- There may be an opening parenthesis missing; perhaps the text was ... garese (case) ricolme di .... --Lambiam 20:07, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- The text linked by the IP has some other oddities ("garese case) ricolme" and later "armti" instead of "armati"). I think the most probable meaning is either "forts, houses,etc..." or the house part clarifying what is a garesa ("forts (houses full of guns...)"). "Garesa" is described as a "forte" or even "castello" in Treccani (not quite a house), so I would propend for the first one. Garese being the plural of garesa and "c" being "e" is otherwise quite clear. If the money and ammunitions are different items in the list or something the houses were full of is also somewhat ambiguos due to the odd puctuation.Personuser (talk) 17:55, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- So if per @Sluzzelin: "garese" is the plural of "garesa" meaning fort, the full translation would become both house and fort, as in "house-fort", as follows: "the Dhulbahante have handed out to them twenty seven 'house-forts' full of rifles, ammunitions and money", correct? Heesxiisolehh (talk) 16:50, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- This is etymological speculation on my part, but perhaps there is some distant relation to the English (from French) "garrison". {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195) 2.122.0.58 (talk) 23:37, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- I actually thought the same, but in a more direct/recent way (the "inglesi" are mentioned in the source and had some business in Somalia). Italian "guarnigione" is related to the same word in a strange way. For some more serious explanation it should be noted that "Garesa", capitalized as a proper noun, is/was used for the museum and the residence of the Governor. I'm not familiar with Somali language or other languages in the area or history and a lot of other stuff that should be considered for a more credible explanation. Personuser (talk) 01:22, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- The term does not occur in the Somali Wikipedia or Wiktionary. The Garesa with a capital G is the building seen here, which may indeed by called a "castle" or a "fort". The best source at the moment is the Treccani use of garese, which implies that the term (locally) means "fort" or "fortress". It is easy to see how the common noun can become the proper noun for a particularly outstanding exemplar. The term is not found in the Somali Wikipedia or Wiktionary, and does not look like Arabic either; the phoneme /g/ does not occur in native Arabic words. If the Dhulbahante relinquished twenty-seven forts into the hands of the English, it is a reasonable conclusion that these were (at the time) Dhulbahante forts. --Lambiam 11:10, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- I see no basis for the qualification "towering" in the translation "towering forts". While the Mogadishu Garesa is imposing enough, I would not call it a towering building. --Lambiam 11:41, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- This is etymological speculation on my part, but perhaps there is some distant relation to the English (from French) "garrison". {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195) 2.122.0.58 (talk) 23:37, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

Tribal signalling?

Is there a term for when people use pejorative language about someone else, but where they are, perhaps unintentionally or subconsciously, giving out information about their own identity (tribe). For example, when used pejoratively, describing someone or some people as "woke" or a "social justice warrior" or a "gammon" or a "wingnut". This signals not only that the other person or people are not members of my tribe, but also to listeners/readers who agree with the statement that they are members of my tribe. It goes further than an insult such as describing someone as "stupid" or "crazy" or "foolish". It isn't anything new: we've been doing it with pejorative racial terms which are far more obviously tribal in nature. -- Colin°Talk 13:56, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- Shibboleth is the first term I think of.. 70.67.193.176 (talk) 17:22, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- Somewhat analogous to Tell (poker) in the language realm. I'm not sure there's any specific linguistic term for this, but according to our "Cant" article, "The term argot is also used to refer to the informal specialized vocabulary from a particular field of study, occupation, or hobby"... -- AnonMoos (talk) 18:41, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- The term "dog whistle" is used, particularly in the United States, to describe a related concept where the language used is superficially innocuous, but has an "in-group" meaning which may be pejorative about the in-group's opponents or targets. The article's See also section may give you some other leads. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 2.122.0.58 (talk) 23:30, 9 June 2021 (UTC)

- I followed the see also section and Loaded language has some of the qualities, in that the words are having a bigger effect that just mere insult. These suggestions all have some attribute of it, but none I think quite capture the whole concept. Perhaps it isn't enough of a real-world pattern for anyone to give it a specific label. -- Colin°Talk 07:32, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- The hateful term nigger lover, designating a white person showing acceptance of black Americans as fellow human beings, implies that the one using the term is a virulent racist and does not tolerate different views in this respect among white folks. The term Judenfreund ("Jew friend") was used analogously in Nazi Germany, and commie lover, a term frequently used by McCarthy,[4] is still regularly found today. These terms are slurs that imply a group standard and flag their users as (proudly) self-identifying with that standard, where the standard-conforming group members are seen as better than the non-standard-conforming group members. I haven't found a more specific term for these non-standard-conforming slurs. For a less hateful example, see landlubber. --Lambiam 10:28, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- I think that in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, "Compsymp" was more likely to be used than "Commie-lover". On Wikipedia, "Comsymp" redirects to article Fellow traveller, but that article doesn't discuss the word at all... AnonMoos (talk) 12:56, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Similar on the communist sympathizer one, pinko was a common term in the US for a long time. --Jayron32 17:20, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- I think that in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, "Compsymp" was more likely to be used than "Commie-lover". On Wikipedia, "Comsymp" redirects to article Fellow traveller, but that article doesn't discuss the word at all... AnonMoos (talk) 12:56, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Also grockle. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 2.122.0.58 (talk) 16:06, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- I've realised this is an aspect of "othering". Wikipedia's Other (philosophy) article touches on it, but is a bit of a rambling mess. There's more on "othering" at The Problem of Othering and the related Guardian article Us vs them: the sinister techniques of `Othering' - and how to avoid them. What is interesting in that article is that the "dog whistle" method, which is so subtle only those "in the know" spot it, is not essential. Populist politicians and media voices feel able to openly insult the "other". Using the language examples listed above wouldn't typically be acceptable in professional writing - it is offensive and deliberately so. Perhaps "derogatory othering" is close to definition? -- Colin°Talk 09:43, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- If you're referring to antagonism which is largely manufactured from top down by political leaders, then there's the book "Hate Spin: The Manufacture of Religious Offense and Its Threat to Democracy" by Cherian George... AnonMoos (talk) 20:40, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

June 10

Meaning of "oldest"

The article about Mikhail Gorbachev says he is the oldest leader of the Soviet Union. As he was the last one, I understand this means "lived the longest". But "oldest" can also mean "born the earliest". Is there a way to distinguish between these? JIP | Talk 01:02, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

I think it is clear that it just means "lived the longest" and *no need* to distinguish it with "born the earliest" per your question ("At age 90, he is the oldest and last surviving leader of the Soviet Union."

"oldest" can also mean "born the earliest". Is there a way to distinguish between these?

)--FMM-1992 (talk) 01:40, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- For verification: List of leaders of the Soviet Union, for curiosity: Bald–hairy#Killed–died (doesn't apply); most long-lived/longest-lived seem the most promising alternatives to me (not a native speaker); anyway Oldest people and probably other articles have the same problem/not a problem and similar solution may be applied Personuser (talk) 02:12, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Age is measured from the moment of origin (for humans, their birth) to some reference time. Reportedly, Methuselah died at the age of 969, so then, when he gave up the ghost, he was (still reportedly) pretty old. Yet, you cannot say, "Methuselah is the oldest biblical patriarch", because the use of the present tense sets the reference time to "now", and in this measure Enoch, having been born before Methuselah, would be older – but, more importantly, the convention in measuring age is that the entity whose age is being measured is still extant at the reference time. One can perhaps say, "Methuselah was the oldest biblical patriarch", the implication being that the reference time was the time of his death. So, for example, Ardi is perhaps the oldest hominid fossil ever found, and while one can say that Ardi was a female Ardipithecus ramidus who lived near the Awash River, one cannot say that Ardi was a very old female Ardipithecus ramidus who lived near the Awash River. But the Ardi fossil is still extant and today very old. In my opinion, the last surviving member of a set is necessarily also the oldest member, by dint of being the unique extant member at the reference time implied by "surviving". Perhaps – even likely – that is not what the author of the sentence meant to say, but then they should have found a different formulation. --Lambiam 09:57, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Disagree. Since all of the Biblical patriarchs are dead, "the oldest" one would be the one who reached the greatest age. In the case under discussion here "oldest leader of the Soviet Union" would seem most likely to mean "that person whose age during their rule was higher than the age of any other ruler during their rules". I'm sure that both the article and my explanation could be better phrased, though. --Khajidha (talk) 16:17, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Age is measured from the moment of origin (for humans, their birth) to some reference time. Reportedly, Methuselah died at the age of 969, so then, when he gave up the ghost, he was (still reportedly) pretty old. Yet, you cannot say, "Methuselah is the oldest biblical patriarch", because the use of the present tense sets the reference time to "now", and in this measure Enoch, having been born before Methuselah, would be older – but, more importantly, the convention in measuring age is that the entity whose age is being measured is still extant at the reference time. One can perhaps say, "Methuselah was the oldest biblical patriarch", the implication being that the reference time was the time of his death. So, for example, Ardi is perhaps the oldest hominid fossil ever found, and while one can say that Ardi was a female Ardipithecus ramidus who lived near the Awash River, one cannot say that Ardi was a very old female Ardipithecus ramidus who lived near the Awash River. But the Ardi fossil is still extant and today very old. In my opinion, the last surviving member of a set is necessarily also the oldest member, by dint of being the unique extant member at the reference time implied by "surviving". Perhaps – even likely – that is not what the author of the sentence meant to say, but then they should have found a different formulation. --Lambiam 09:57, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- As with any categorical statement, you first need to define what you mean by oldest. I could read "the oldest Soviet leader" in two ways: 1) who was the oldest while they served in the office and 2) Who, having served in the office at any time, eventually lived to the oldest age. At 90 years old today, Gorbachev only meets the second definition; he was only leader of the Soviet Union until 1991, at which time he was 60 years old; younger than several of the other people to have held that role. Gorbachev's immediate predecessor, Konstantin Chernenko, was 74 as leader of the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev served until he was 76, several others also served in to their 70s. --Jayron32 16:32, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- I wouldn't use "oldest" for your second definition. That would be "longest lived". --Khajidha (talk) 16:33, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- William Ewart Gladstone is described in several reputable internet articles as "Britain's oldest prime minister", [5] [6] meaning that he was the oldest to serve in that office (not the longest-lived who was James Callaghan). Alansplodge (talk) 10:51, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- I wouldn't use "oldest" for your second definition. That would be "longest lived". --Khajidha (talk) 16:33, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

Been thinking about this some more and realized there are three things that some people might get confused: oldest, longest lived, and eldest. For clarification I will use United States presidents,as I am more familiar with them than Russian/Soviet leaders.but the patterns still apply. 1) "Oldest president" - the one who attained the greatest age while in office. Currently, this is Joe Biden. 2) "Longest lived president" - the one who attained the greatest age before death, regardless of how long they had been out of office. Currently, this is Jimmy Carter. 3) "Eldest president" - the one who was born before all others. This is George Washington. --Khajidha (talk) 17:43, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

Latin translation request (work related)

Hey language desk

My supervisor at work has a significant birthday coming up and we're working on getting a few things, and one of them requires a Latin translation.

So we all know the "Don't Forget - You're Here Forever" plaque from The Simpsons. It's one of those, the Latin being used to make it look profound and important. I know, this is how offices are, it's that kind of 9-5 office life.

I've done some Google-ing, because I didn't want to just come here cold. I've got phrases like "'nunquam obliviscere' and "hic in perpetuum" and ""usque in sempiternum", which I think is close to the right answer but not quite there yet.

So please, if I'm allowed, could I ask the language desk to help me and my supervisor a help, and confirm what the best translation would be? Many thanks x doktorb wordsdeeds 10:28, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- I guess I never saw that episode of "The Simpsons" (not sure what message it's intended to convey). The first question when translating into Latin is whether it's addressed to a single person (tu, noli) or to multiple people (vos, nolite)... AnonMoos (talk) 12:50, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Maybe "Ne obliviscaris te hic in perpetuum esse"? (You don't really need the "esse" though.) Adam Bishop (talk) 13:19, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Of course that translation makes the choice to use singular. I think that "adesse" would be more in the spirit of Latin than "hic...esse". AnonMoos (talk) 14:05, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Yeah that does sound better! By the way, the message in the Simpsons episode is that Homer quit his job and had to grovel to get it back and now his boss is trying to crush his spirit, but he covers up the letters on the sign with pictures of Maggie so it says "Do it for her". Adam Bishop (talk) 14:18, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Doktorbuk, here's the difference between perpetuum and sempiternum:

- perpetuum is an adequate description of a finite being's experience of "forever" in this life. For example, God's laws given to Moses were "perpetual" for the Jews.

- sempiternum describes God's eternity: without beginning, without end, unto the ages of ages. If you really want to go for hyperbole and a bit of a ridiculous edge, this is what I'd choose. It's not realistic, but it seems that the idea of the plaque is to be humorous? Elizium23 (talk) 13:26, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Is the plaque from The Simpsons some kind of play on memento mori? Personuser (talk) 14:23, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Personuser, I don't know - the clip is findable on YouTube, though it is a copyvio. Elizium23 (talk) 14:27, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- Thank you all so much. It is for a light hearted present so I know that the Latin doesn't need to be exactly perfect, but I'm also well aware that it's too complex a grammar for throwaway Google translate. I'll use your answers and responses and see how we ago. Thanks again x doktorb wordsdeeds 17:16, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- In English you can omit the conjunction "that" from "Don't Forget

thatYou're Here Forever", but I don't think you can do the same in Latin. If you do, it seems these are unrelated sentences: "Don't forget! ... Oh, and, by the way, you're here forever." In Latin one can use a conjunction like ut or Late Latin quia, or use the accusativus cum infinitivo to indicate that which should not be forgotten. Also, "adesse" means "to be present", but not necessarily to be present here. "Be there" in "Be there or be square" can be translated as adeste. "Don't Forget That You Attend [Here] Forever" is not quite right, and I guess no word-by-word translation conveys the core message of being stuck. I'd go for a circumlocution: "Don't Forget That Your Place is Forever Here", or "noli oblivisci locum tuum semper hic esse". For an inscription, use majuscules: "NOLI OBLIVISCI LOCVM TVVM SEMPER HIC ESSE" (note the majuscule "V" instead of "U"). (Or substitute the synonym "AETERNO" for "SEMPER".) Bonus question: make a translation such that you can cover up parts to spell the message: "DO IT FOR HER" ("PRO EA FAC"). --Lambiam 19:58, 10 June 2021 (UTC)- Thank you too! doktorb wordsdeeds 20:38, 10 June 2021 (UTC)

- In English you can omit the conjunction "that" from "Don't Forget

Lambiam -- I don't understand your point about the conjunction, since Adam Bishop used an accusative-with-infinitive construction (something you mentioned), which is very different from a second finite clause. My Latin dictionary says that obliviscor can take an ACI. Also "Hic sum" (with long I vowel) is a literalistic translation of "I'm here", but in many contexts, ancient Romans would more likely have said "Adsum"... AnonMoos (talk) 00:56, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- My translation also uses an ACI; I overlooked Adam Bishop's version. I think though that the infinitive in the ACI is mandatory, also for the copula esse. (Compare Ceterum autem censeo Carthaginem esse delendam.) Adsum sounds to me like the response Present during a roll call. If ET had spoken Latin, they might have said "Hic demum adero". But the sense in the Simpsons plaque is not "You'll always be present". Disclosure: I am not a native Latin speaker. --Lambiam 08:40, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

June 11

Some new slang that the kids be using

I'm apprehensive about asking this here when I could just as easily go to Urbandictionary or some website for parents that claims to be informed about teen slang of the current times, but many of those sites tend to offer meanings that differ greatly from each other, and I stubbornly wanted to refrain from constantly relying on Urbandictionary, Know Your Meme, Stack Exchange, or some other cruddy place just to figure out where some recently born slang came from, or how it makes any lick of sense. Thanks to the very nature of slang (and magnified by social media usage), there is barely a consistency for lots of terms these days, to the point where I can no longer deduce the meanings of some of them by common sense alone (which is at least easy to do for most videogame slang). It took me months to figure out what "yeet", "on fleek", or "thot" meant, let alone where they originated. Probably doesn't help that I'm someone not hounded by social media out of a conscious choice. So to me its either Urbandictionary, with all its messy, volatile, and at times ambiguously nonsensical "advisement", or here, where its calmer and I'm more familiar with, but dealing with folks who are very likely 20-30 years my senior.

For now, I would like to confirm the origins and intended meanings of the terms "sus", "based", "periodt", and a certain sense of "cringe". For the former two, I've got some idea, if it really is true that "sus" originated as jargon from some multiplayer game that got popular very recently, and "based" being deduced as a sort of synonym for "unbiased" or "having a solid source or foundation", from how I've seen it used. For "periodt" however, I am completely clueless. Whether its an intentional misspelling of peridot or not, I don't know. The same with "cringe" as an interjection or exclamation. I understood its usage as a synonym for "embarrassing" or "cheesy", but I am unsure what meaning is intended when its just shouted out with little outside context. --72.234.12.37 (talk) 02:39, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- Despite this being a "reference" desk I am going to venture an opinion here, which is that these kids are not getting this vocabulary from books or dictionaries, parents or teachers, but by using words that their mates are using so as to appear as cool as them. So far, so obvious, but I would also venture that they do not discuss the precise meaning of these terms with their peers, because that would not be cool. This is why they keep saying "You know what I mean?" or "You know what I'm saying?" Because they know full well that these terms do not have precise meanings and they are not really sure what they are communicating.--Shantavira|feed me 08:03, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- That is a fair assessment and makes sense, considering the "groupie" social mindset that starts becoming prevalent at around the puberty age range. People seek acknowledgement and acceptance, illusion or not. That is a part of being an innately social creature. I can definitely say I've been on both giving and receiving ends of "You know/get what I mean/saying?" whenever sufficient detail of something could not be communicated properly for whatever reason.

- In hindsight, I may be holding some frustration that I can no longer understand what my peers are saying, because they are more quick to adopt the current slang than I am, and I remain stuck in my era. I've always believed slang to be a generational phenomenon, a marker of sorts that unintentionally highlights when a speaker was born and raised, much like how a regional dialect would do the same for where someone was raised. Also, slang back in my childhood was for the most part, a lot more straightforward than most terms now. At least for me, the meanings of "aiight", "Psych!", "banger", "the shit/bomb/tits", "chillaxin'", or "homie" are more obvious and fluid than say, "bae", "flex", "hits different", "mansplaining", "mood", or "a Karen". Hell, I'm inclined to believe even "booyah" makes more sense than half the stuff coming from the mouths of teens nowadays. But of course, familiarity with one's own era is the main bias here. --72.234.12.37 (talk) 02:37, 13 June 2021 (UTC)

- Wiktionary gives the etymology of sus as being a clipping of suspicious. For based, the etymology given is that it is a reference to freebase cocaine, via basehead, coined by Lil B. The meanings given are (1) "Not caring what others think about one's personality, style, or behavior; focused on maintaining individuality"; (2) "Praiseworthy and admirable, often through exhibiting independence and security". The interjection periodt is explained as an altered spelling of period, used to underscore a statement or (much like the unaltered interjection in North-American English) to indicate that it is not open to dispute. No interjection cringe is listed there, but the meaning seems pretty transparent: "This makes me cringe" (mostly from vicarious embarassment). --Lambiam 08:15, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- In England, we even had a Sus law. Alansplodge (talk) 10:40, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- The game that "sus" grew up in the culture alongside of is Among Us, an online multiplayer version of the old social game Mafia (party game). --Jayron32 13:51, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- Since Jayron32 doesn't explain what "culture" he is talking about, I can't directly challenge that statement. But having grown up in England, I have been familiar with "suss" and "suss out" as a normal if informal part of English at least since 1970, and I've never heard of the game Mafia before ten minutes ago. --ColinFine (talk) 17:41, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- See also suss out. Alansplodge (talk) 10:15, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- Ah okay, so that helps to dispel my thought that "sus" is an esoteric term within Among Us ("His activity was pretty sus"), in much the same manner as "ganking" for League of Legends, "poggers" for Twitch streamers, or "simp" for fans of virtual Youtubers. I've also been told it is a clipping of "suspect".

- For ColinFine, I'm sure Jayron meant to say "The video game community that "sus" grew up alongside is that of Among Us", as in Among Us players are the reason why "sus" gained widespread use thanks to the game's recent popularity surge.

- As for the Mafia game, I've heard of the concept before, but under many different names and variations; the most common name I've come across being "Werewolf", and the most hilarious I've known being Secret Hitler.--72.234.12.37 (talk) 02:37, 13 June 2021 (UTC)

- To me, based has a connotation of reckless courageousness, with a side of being correct. Temerarius (talk) 21:51, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- That makes sense with the usage I've seen, so less of an "unbiased" option or opinion and more of "bold" or "audacious". Still trying to wrap my head around "periodt", and failing. Like Lambiam mentions, "period" already exists, equivalent to "full stop", "no contest", "we're done here", and many more, so I don't really see what's different from adding a T at the end. I honestly thought someone was too lazy to type an exclamation mark or something. --72.234.12.37 (talk) 02:37, 13 June 2021 (UTC)

- See also suss out. Alansplodge (talk) 10:15, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

Primarch

So I found myself replaying Mass Effect again, courtesy of the legendary edition, and the word "primarch" caught my attention. In-universe, the word refers to the highest rank possible a member of the Turian race can obtain through a meritocratic hierarchy of 27 distinct "citizenship tiers". Taking into consideration that the Turian civilisation was directly inspired by the Romans, the closest Latin word I know of that it could possibly be derived from is primārius, while its intended meaning of "leader of the world's government or colony group" may be modelled after Prīnceps. I am also aware of the word's presence in Warhammer 40000, so perhaps it started or originated from there, then spread over time to several other works, including Mass Effect (though I'm not exactly aware of many other works of fiction that extensively used the word "primarch").

So I guess what I'm asking is: Was "primarch" ever a legitimate word, or was it just an invention by some science fiction creators to use in whatever civilisations/factions that are utilising the trope of "space Romans"? Latin dictionaries I've looked online suggest that the word does not exist. --72.234.12.37 (talk) 02:39, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- For what it's worth, it's not in (my edition of) the Oxford English Dictionary, which suggests it hasn't been used historically. The nearest is "primar", an obsolete Scots term (from primarius) for the head of a university.

- That said, its intended meaning (literally "first ruler") seems to me to be fairly obvious to anyone acquainted with Latin, even at one remove via Latin elements used in English. I'm genuinely surprised that it's actually (as far as I can tell) a modern neologism.

- From the ISFDB, it has only been used in a title in SF/Fantasy for The Primarchs, an anthology edited by Christian Dunn and published by Black Library/BL Publishing on 29 May 2012 in the US. This is part of a series called The Horus Heresy set in the Warhammer 40,000 universe, and a Wikipedia search shows the term has previously been used in other Warhammer works, so it seems this might be its origin, but it's so obvious a coinage that the Warhammer writers may have picked it up from a previous use elsewhere.

- "Primarch" appears in Rottweiler as part of the name of a dog photographed in 2008, but since the Warhammer franchise has, I gather, been translated into German, this doesn't prove an independent origin. The same criterion applies to the 2019 rock-opera album The Clockwork Prologue by Gandalf's Fist which features a character called "The Primarch."

- All other appearances of "Primarch(s)" in Wikipedia are related to Warhammer 40,000 or to the Japanese franchise Final Fantasy which seems to have cross-pollinated with it – I can't tell which of these two might have primacy of usage. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 2.122.0.58 (talk) 04:02, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- Prim- is a Latin root, while the suffix -arch comes from Greek and is rarely found attached to Latin roots. There are very few exceptions. The only one in common use is matriarch, modelled after patriarch (which is of true Greek provenance). Another one, really rare, is the hybrid neologism omniarch[7] (chosen by the author for unknown reasons instead of more regular *panarch, from a fully Greek but unattested *πανάρχης). Primarch appears to be, likewise, a neologism. --Lambiam 07:54, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- The OED has the fully-Greek protarch, from proto- + arch, described as "rare" and defined as "a chief ruler; (in extended use) any leader." AndrewWTaylor (talk) 08:54, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- By "cross-pollinated", did you mean to say that one work may have directly or indirectly influenced the other? --72.234.12.37 (talk) 02:37, 13 June 2021 (UTC)

- Yes. For example, the final paragraph of the Final Fantasy article's Legacy section includes the sentence: "Mass Effect art director Derek Watts cited Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within as a major influence on the visual design and art direction of the series." Since they are both long-running franchises in similar niches, and have been running concurrently for over 13 years, it seems not unlikely that other less obvious influences in both directions have occurred: some of the Wikipedia sub-articles I found by searching on "Primarch" also seemed to suggest mutual influence.

- Perhaps we should also consider whether Primark, a commercial name invented in 1973, may have prompted the later coining of "Primarch." {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 2.122.0.58 (talk) 03:51, 13 June 2021 (UTC)

- Prim- is a Latin root, while the suffix -arch comes from Greek and is rarely found attached to Latin roots. There are very few exceptions. The only one in common use is matriarch, modelled after patriarch (which is of true Greek provenance). Another one, really rare, is the hybrid neologism omniarch[7] (chosen by the author for unknown reasons instead of more regular *panarch, from a fully Greek but unattested *πανάρχης). Primarch appears to be, likewise, a neologism. --Lambiam 07:54, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

What does "same set" refer to?

Sentence: These programs ran until March 30, 1985, using the same set that would later be used by Jim Crockett when he purchased the WWF time slot from McMahon (see below). Source: Black Saturday (professional wrestling)

What does "same set" refer to? Rizosome (talk) 13:05, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- I've added Jayron's link to the article. (Who says the Ref Desk doesn't help improve Wikipedia?) In the old days, movie sets would be used over and over again, for different things. Thanks to home video releases, eagle-eyed observers have found many recurring sets, one famous one being a New York City street with brownstones and stoops, used in many films over the years. Building those sets was a cost-savings by studios. There are also naturally-occurring "sets", such as Monument Valley, which was used as a backdrop in many a John Ford western. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 13:58, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- A famous British example is Carry on Cleo, a low budget comedy, that used the same set and costumes as Cleopatra, an epic blockbuster which "was the most expensive film ever made up to that point and almost bankrupted 20th Century Fox". Alansplodge (talk) 10:08, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- See also Backlot, where semi-permanent sets were built and reused. Alansplodge (talk) 12:51, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- A famous U.S. example is the set of The Andy Griffith Show (a/k/a Mayberry RFD), which was used for part of the legendary original Star Trek episode "City on the Edge of Forever". --Orange Mike | Talk 18:45, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- That same backlot was used for the first 26 episodes of Adventures of Superman. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 19:01, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- A famous British example is Carry on Cleo, a low budget comedy, that used the same set and costumes as Cleopatra, an epic blockbuster which "was the most expensive film ever made up to that point and almost bankrupted 20th Century Fox". Alansplodge (talk) 10:08, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

Why do American rules say "this." and never "this". should be used??

Many online sites say that Americans are supposed to write "this." and never "this". regardless of which is more logical. But they're not helpful with the reason we have to write "this." even if "this". is more natural. Does it derive from the rules of Latin?? Georgia guy (talk) 14:02, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- Can you provide a full sentence with that usage? Or are you merely talking about the placement of punctuation with quotation marks? <-Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots-> 14:12, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- Georgia guy, is this something like MOS:LQ? Elizium23 (talk) 14:13, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- Yes; it's about how to place punctuation adjacent to quotation marks. Georgia guy (talk) 14:39, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- (edit conflict) Not all rules (or even most rules) have reasons why, beyond "consistency". Which is to say, someone sets a rule arbitrarily, solely for the purpose of having a consistent system, and there is no reason why that rule was chosen over a different, but equal, rule. It just is. And by "someone" I don't mean "someone" so much as "indeterminable people". This blog post hosted by the Chicago Manual of Style states "This traditional style has persisted even though it's no longer universally followed outside of the United States and isn't entirely logical." and goes into some detail on this quirk of American English style. The rule first appeared in the 1906 Chicago Manual of Style (2 years after the first edition) and it appears that the influence of the CMOS was great enough that it propagated through all of the major AmEng style guides in the early 20th century. MLA recommends the same style, and that page also cites Strunk and White was recommending it in 1959. The MLA citation does cite typographic conventions as the main reason for it (the same situation that mandated the "two spaces after a period at the end of a sentence" rule), and that modern digital typography has obviated the original need for the rule. I will also note that the rule is slowly changing, the Purdue Online Writing lab (OWL), a very commonly used online style guide, is no longer as stringent in its application of the rule as most other US style guides are. --Jayron32 14:20, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- Some things are indeed arbitrary, but others are plain illogical and deserve condemnation. Such as including a trailing comma inside closing quotation marks, when the comma was never part of the quote. "You are not my father," he said. Triple yuck!!! -- Jack of Oz [pleasantries] 22:38, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- One also wonders what proponents of quote mark switching propose for a sentence like, "Am I my brother's keeper?", he asked. --Lambiam 09:19, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- Some things are indeed arbitrary, but others are plain illogical and deserve condemnation. Such as including a trailing comma inside closing quotation marks, when the comma was never part of the quote. "You are not my father," he said. Triple yuck!!! -- Jack of Oz [pleasantries] 22:38, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

The Wikipedia article is Quotation marks in English#Order of punctuation. British or "logical" quoting is based on including within quote marks only that which is actually quoted. American quoting seems to be based at least partly on an old printing practice of printing quote marks directly above commas and periods (stops) to save space. When this was no longer done, putting the punctuation after the quote mark seemed to some to be visually uglier than putting the punctuation before the quote mark. The Wikipedia "Manual of Style" recommends British conventions be used for the positioning of quote marks with respect to other punctuation (many American computer geeks have preferred logical punctuation for decades), but recommends American conventions for outermost quote marks being double... AnonMoos (talk) 21:00, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- Any reason?? Georgia guy (talk) 21:04, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

The reason is because

When I was in school, my teachers said one should never use the phrasing "the reason is because." Yet I have heard this expression used by educated people and seen it used in reliable sources. How accepted is this usage? TFD (talk) 15:12, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- It rather depends on how formally (or in what register) one is writing or speaking. It's an easy wording to fall into when speaking spontaneously, and doubtless I've done so myself, but in careful and formal speech or writing most would avoid it, because its tautology ("the reason is" and "because" mean the same and can stand alone) irritates some auditors or readers. This is something that careful speakers and writers generally try to avoid, even when the particular irritant usage is not actually incorrect, so as not to break their audience's attention. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 2.122.0.58 (talk) 15:49, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- There are more than two levels of formality involved here. "The reason [for] ... is [that] ..." and "[Something is the case] because ..." are certainly considered by everyone to be unobjectionable in formal prose. As Former 87.81.230.195 says, "The reason ... is because ..." is considered by many to be pleonastic. Still fewer folk approve of the construction "The reason why ... is because ..." Deor (talk) 16:02, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- Like many, many, many of the grammatical proscriptions that people used to insist on in the past, but which have always been bullshit, this is right there with "splitting infinitives" and "ending sentences with prepositions". This proscription has a singular source, basically one grammarian in 1926 got a bug up his ass about it, and then it was decided it was gospel. As seen here, that grammarian was Henry Watson Fowler, and there is no evidence that the rule existed before he wrote it down; it seems to have been an annoyance peculiar to himself, but his status as an authority on the English language meant that prescriptive linguists have latched on to it since then; descriptive linguists have noted, however, that aside from Fowler and those that followed, it has never been a marked construction in English usage. The blog post I cite there notes several prominent uses of the construction from both before and after Fowler invented the proscription against it, by several prominent and learned writers from all over the Anglosphere. Which is not to say that you should start using it. Both "The reason is... because..." and "The reason is... that..." are perfectly acceptable, and if one does not fit into your idiolect, feel free to not use it. But there is no "rule" in normal English against it. --Jayron32 16:18, 11 June 2021 (UTC)

- And, in case you want a better authority than the Motivated Grammar blog, try Merriam Webster on for size "

In sum, "the reason is because" has been attested in literary use for centuries. If you aren't comfortable using the phrase, or feel that it's awkward, don't use it. But maybe lay off the criticism of others—there's really no argument against it.

" The Merriam Webster entry cites a usage of "the reason is... because..." to E. B. White of Strunk and White fame. If that's not an endorsement that the usage is cromulent, I don't know what is. --Jayron32 16:22, 11 June 2021 (UTC)- Yes, but given Strunk & White's endorsement of ludicrous punctuation as noted in the thread above, I hardly think their opinion is to be relied upon. DuncanHill (talk) 10:21, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- And, in case you want a better authority than the Motivated Grammar blog, try Merriam Webster on for size "

- This could be a difference between modern Commonwealth and American usage, like [1]"this". and "this." TFD (talk) 14:07, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

References

- ^ "this."

- Those look identical, unless I need my glasses checked. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 18:59, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- I think it's about the full stop inside or outside the inverted commas, but they are indeed identical. Alansplodge (talk) 19:04, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- Those look identical, unless I need my glasses checked. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 18:59, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- Sorry, I corrected it. In American English, “By convention, commas and periods that directly follow quotations go inside the closing quotation marks” (MLA).[8] But in Commonwealth English, they are placed before the closing quotation marks. It's useful to know if one is writing or editing articles for publication in different countries. TFD (talk) 19:54, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- Uh.... I think you've gotten confused again. I think you meant to say that "in Commonwealth English, they are placed after the closing quotation marks." --Khajidha (talk) 22:07, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- Sorry, I corrected it. In American English, “By convention, commas and periods that directly follow quotations go inside the closing quotation marks” (MLA).[8] But in Commonwealth English, they are placed before the closing quotation marks. It's useful to know if one is writing or editing articles for publication in different countries. TFD (talk) 19:54, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- That doyen of British grammar, Henry Watson Fowler, has this to say on the subject:

- The reason why so few marriages are happy. is because young ladies spend their time in making nets, not in making cages.

- The reason Adam was walking along the lanes at this time was because his work for the rest of the day lay at a country-house about three miles off.

- Jonathan Swift and George Eliot could be called for the defence of the modern journalist who writes The reason was because they had joined societies which becane bankrupt, or The only reason for making a change in the law is because the prostitute has an annoyance value. But there is obviously a tautological overlap between reason and because: the young ladies' so spending their time, the work's lying in that direction, their joining those societies and the prostitute's having an annoyance value are the reasons, and they can be paraphrased into the noun clauses that the young ladies spend etc., but not into the adverbial clauses because the young ladies spend etc. And so, although the reason is because often occurs in print and oftener in speech, the reason is that is more correct and no more trouble.

- A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, Second Edition 1965, pp. 504-505. Alansplodge (talk) 22:17, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

June 12

What does "signed for one day" mean?

Patrick asks Dana about money:

Dana: It had been signed for one day by the staff at Grande Liquor, and they missed it. It was in the trolley, so...

Patrick: You stole it?

Dana: Yeah, I f*cking stole it.

What does "signed for one day" mean? Rizosome (talk) 16:22, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- You have not given the source, Rizosome, so I can only guess; but my guess is it means "on one particular day, somebody signed for it", i.e. signed a docket that it had been received. --ColinFine (talk) 17:48, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- Agreed. Rizosome, I think you are not properly separating the words in your mind. There are two phrases running together here: "signed for" and "one day". --Khajidha (talk) 18:58, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

- It is dialogue from the film Wrath of Man, H interrogating Dana about her cash stash. --Lambiam 22:48, 12 June 2021 (UTC)

June 13

Bilateral talks

When a national leader sits down and has a talk or series of talks with another national leader, why is it necessary to refer to this as "bilateral talks"? That just tells us there were two people involved ... which we already knew. Same query for "multilateral talks" when there are many people involved. -- Jack of Oz [pleasantries] 03:07, 13 June 2021 (UTC)

- I think the emphasis is on two (or more) "sides" rather than individuals, and I understand the implication to be that such talks involve formulating, presenting and mutually agreeing official policies of international significance, rather than just exchanging views ("frankly" or otherwise). {The poster formerly known as 87.81.2390.195} 2.122.0.58 (talk) 04:02, 13 June 2021 (UTC)