Crusading movement

The Crusading movement was one of the most important elements and defining attributes of late medieval western culture. It impacted almost every country in Europe as well as in the Islamic world; touching many aspects of life while influencing the Church, religious thought, politics, the economy, and society. It had a distinct ideology that was evident in texts describing, regulating, and promoting crusades. It began with a call from Pope Urban II for an armed pilgrimage to recover the Christian holy places in Jerusalem. In 1095, he promised participants spiritual reward during a church council in Clermont, France. The expedition led to the founding of four crusader states in Syria and Palestine and inspired further military endeavours and popular movements, now known collectively as crusades. Roman Catholic church leaders developed the movement by offering spiritual reward to those who fought for the defence of the holy places and extended this to fighting Muslim rulers in the Iberian Peninsula, pagan tribes in the Baltic region, primarily in Italy against enemies of the Papacy, and non-Catholic groups. Supporters who were unable or unwilling to fight could acquire the same spiritual privileges through donations.

The legal and theological foundations were formed from the theory of Holy War, the concept of pilgrimage, Old Testament parallels to Jewish wars instigated and assisted by God, and New Testament Christocentric views on forming individual relationships with Christ. Participants in crusade were viewed as milites Christi, or Christ's soldiers. Volunteers took a vow and received plenary indulgences from the Church. Motivation may have been the forgiveness of sin, feudal obligation to participate in their lords' military actions, or honour and wealth.

Muslims, Jews, pagans, and non-Catholic Christians were frequently killed in large numbers. Islamic holy war known as Jihad revived; schism grew between Catholicism and Orthodoxy; and antisemitic laws were made. Crusading ventures expanded the borders of western Christendom, consolidated the collective identity of the Latin Church under papal leadership and reinforced the connection between Catholicism, feudalism and militarism. The republics of Genoa and Venice flourished, establishing communes in the crusader states and expanding trade with eastern markets. Accounts of crusading heroism, chivalry and piety influenced medieval romance, philosophy and literature. Societies of professional soldiers under monastic vows emerged as military orders in the crusader states and at western Christendom's Iberian and Baltic borderlands. Trading in spiritual rewards prospered, scandalising pious Catholics, and developing into one of the causes of the 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Background

The First Crusade inspired a movement that became one of the most significant defining elements and attributes of late medieval western culture.[1] The crusading movement impacted almost every area of life in every country in Europe through influence on the Church, religious thought, politics, the economy, society and generating its own literature. It also had an enduring impact on the history of the western Islamic world.[2] A distinct ideology is evident in the texts that described, regulated, and promoted crusades. These were defined in legal and theological terms based on the theory of Holy War and the concept of pilgrimage. Theologically there was a merging of Old Testament parallels to Jewish wars instigated and assisted by God with New Testament Christocentric views on forming individual relationships with Christ. Holy war was based on bellum iustum, the ancient idea of just war. Augustine of Hippo Christianised this, and canon lawyers developed it from the 11th century into bellum sacrum, the paradigm of Christian holy. The criteria were holy war must be initiated by a legitimate authority such as a pope or emperor considered as acting on divine authority; that there was causa iusta, a just cause such as serious offence, overt aggression or injurious action; a threat to Christian religion; and intentio recta waged with pure intentions like the good of religion or co-religionists. In the 12th century, Gratian and the Decretists elaborated on this, and Thomas Aquinas refined it in the 13th century. The idea that holy war against pagans could be justified simply by their opposition to Christianity, suggested by Henry of Segusio, was never universally accepted. Crusades were considered special pilgrimages, a physical and spiritual journey under ecclesiastical jurisdiction and the protection of the church. Pilgrimage and crusade were penitential acts; popes considered crusaders earned a plenary indulgence giving remission of all God-imposed temporal penalties.[3]

Crusades were described in terms of Old Testament history analogous to the Israelites' conquest of Canaan and the wars of the Maccabees. This presented wars against the enemies of Israel waged by God's people, under divine leadership against the enemies of a true religion. The Crusades were believed to be sacred warfare conducted under God's authority and support. Old Testament figures such as Joshua and Judas Maccabaeus were presented as role models. Crusaders were viewed as milites Christi Christ's soldiers forming the militia Christi or Christ's army. This was only metaphorical up to the first crusade, when the concept transferred from the clerical to secular. From the end of the 12th century the terms crucesignatus or crucesignata meaning "one signed by the cross" were adopted. Crusaders attached crosses of cloth to their clothing marking them as a follower devotee of Christ, responding to the biblical passage in Luke 9:23 "to carry one's cross and follow [Christ]". The cross symbolised devotion to Christ in addition to the penitential exercise. This created a personal relationship between crusader and God that marked the crusader's spirituality. It was believed that anyone could become a crusader, irrespective of gender, wealth, or social standing. Sometimes this was seen as an imitatio Christi or imitation of Christ, a sacrifice motivated by charity for fellow Christians. Those who died campaigning were seen as martyrs. The Holy Land was seen as the patrimony of Christ; its recovery was on the behalf of God. The Albigensian Crusade was a defence of the French church, the Baltic Crusades were campaigns conquering lands beloved of Christ's mother Mary for Christianity.[4]

From the beginning, crusading was strongly associated with the recovery of Jerusalem and the Palestinian holy places. The historic Christian significance of Jerusalem as the setting for Christ's act of redemption was fundamental for the First Crusade and the successful establishment of the institution of crusading. Crusades to the Holy Land were always met with the greatest enthusiasm and support, but crusading was not tied exclusively to the Holy Land. By the first half of the 12th century, crusading was transferred to other theatres on the periphery of Christian Europe: the Iberian Peninsula; north-eastern Europe against the Wends; by the 13th century, the missionary crusades into the Baltic region; wars against heretics in France, Germany, and Hungary; and mainly Italian campaigns against the papacy's political enemies. Common to all were Papal sanction and the medieval concept of one Christian community, one church, ruled by the papacy separate from gentiles or non-believers. Christendom was a geopolitical reference, and this was underpinned by the penitential practice of the medieval church. These ideas rose with the encouragement of the Gregorian Reformers of the 11th century and declined after the Reformation. The ideology of crusading was continued after the 16th century mainly by the military orders, but dwindled in competition with other forms of religious war and new ideologies.[5]

Definition

Crusades were the fighting of Christian religious wars, the authorisation and objectives of which derived from the pope through his legitimate authority as Vicar of Christ. Combatants received forgiveness for confessed sin, legal immunity, freedom from debt interest and both their family and property was protected by the church. They swore vows like those of a pilgrimage, the duration of which was determined by completion, by absolution or by death. Those who died in battle or completed the vow were considered martyrs with eternal salvation. The first, original and best-known crusade was the expedition to recover Jerusalem from Muslim rule in 1095. For centuries, the Holy Land was the most significant factor in terms of rhetoric, imagination, and ideology.[6]

At first, the term crusade used in modern historiography referred to the wars in the Holy Land beginning in 1095. The range of events to which the term has been applied has been extended, so its use can create a misleading impression of coherence, particularly regarding the early crusades. The Latin terms used for the campaign of the First Crusade were iter, "journey", and peregrinatio, "pilgrimage".[7] The terminology of crusading remained largely indistinguishable from that of Christian pilgrimage during the 12th century. This reflected the reality of the first century of crusading, when not all armed pilgrims fought and not all who fought had taken religious vows. It was not until the late 12th and early 13th centuries that a more specific "language of crusading" emerged.[8] Pope Innocent III used the term negotium crucis or "affair of the cross". Sinibaldo Fieschi, the future Pope Innocent IV, used the terms crux transmarina—"the cross overseas"—for crusades in the Outremer (crusader states) against Muslims and crux cismarina—"the cross this side of the sea"—for crusades in Europe against other enemies of the church.[9] The modern English "crusade" dates to the early 1700s.[10][A] The term used in modern Arabic, ḥamalāt ṣalībiyya حملات صليبية, lit. "campaigns of the cross", is a loan translation of the term "crusade" as used in western historiography.[11]

French Catholic lawyer Étienne Pasquier, who lived from 1529 to 1615, is thought to be the first historian to attempt the numbering of each crusade in the Holy Land. He suggested there were six.[12] In 1820 Charles Mills wrote History of the Crusades for the Recovery and Possession of the Holy Land in which he counted nine distinct crusades from the First Crusade of 1095–1099 to the Ninth Crusade of 1271–72. This convention is often retained for convenience and tradition, even though it is a somewhat arbitrary system for what some historians now consider to be seven major and numerous lesser campaigns.[13]

The term "Crusade" may differ in usage depending on the author. In an influential article published in 2001, Giles Constable attempted to define four categories of contemporary crusade study:

- Traditionalists such as Hans Eberhard Mayer restrict their definition of the Crusades to the Christian campaigns in the Holy Land, "either to assist the Christians there or to liberate Jerusalem and the Holy Sepulcher", during 1095–1291.[14]

- Pluralists such as Jonathan Riley-Smith use the term Crusade of any campaign explicitly sanctioned by the reigning Pope.[15] This reflects the view of the Roman Catholic Church (including medieval contemporaries such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux) that every military campaign given Papal sanction is equally valid as a Crusade, regardless of its cause, justification or geographic location. This broad definition includes attacks on paganism and heresy such as the Albigensian Crusade; the Northern Crusades and the Hussite Wars; and wars for political or territorial advantage such as the Aragonese Crusade in Sicily, a Crusade declared by Pope Innocent III against Markward of Anweiler in 1202;[16] one against the Stedingers; several (declared by different popes) against Emperor Frederick II and his sons;[17] two Crusades against opponents of King Henry III of England[18] and the Christian re-conquest of Iberia.[13]

- Generalists such as Ernst-Dieter Hehl see Crusades as any holy war connected with the Latin Church and fought in defence of the faith.

- Popularists including Paul Alphandery and Etienne Delaruelle limit the Crusades only to those characterised by popular groundswells of religious fervour—that is, only the First Crusade and perhaps the People's Crusade.[19][20]

Ideological development

Before the Crusades

The use of communal violence was not alien to early Christians. A Christian theology of war evolved when Roman citizenship became linked to Christianity and citizens were required to fight against the Empire's enemies. The 4th-century theologian Augustine maintained that an aggressive war was sinful, but acknowledged a "just war" could be rationalised if it was proclaimed by a legitimate authority such as a king or bishop, was defensive or for the recovery of lands, and without an excessive degree of violence. These principles led to the development of a doctrine of holy war in the 13th century by Thomas Aquinas, canon lawyers and theologans.[21] Historians, such as Carl Erdmann, thought the Peace and Truce of God movements restricted conflict between Christians from the 10th century; the influence is apparent in Pope Urban II's speeches. Later historians, such as Marcus Bull, assert that the effectiveness was limited and it had died out by the time of the crusades.[22]

Pope Alexander II developed a system of recruitment via oaths for military resourcing that Gregory VII extended across Europe.[23] Christian conflict with Muslims on the southern peripheries of Christendom was sponsored by the Church in the 11th century, including the siege of Barbastro and fighting in Sicily[24] In 1074 Gregory VII planned a display of military power to reinforce the principle of papal sovereignty. His vision of a holy war supporting Byzantium against the Seljuks was the first crusade prototype, but lacked support.[25] Theologian Anselm of Lucca took the decisive step towards an authentic crusader ideology, stating that fighting for legitimate purposes could result in the remission of sins.[26]

Urban II and the birth of the crusading movement

It was Odo of Chatillon, who took the name Urban II on his election to the papacy, who initiated the crusade movement with the First Crusade. He was elected pope at Terracina in March 1088 while the imperialist antipope, Pope Clement III. controlled Rome, and he was unable to enter Rome until 1093 when Clement III withdrew. From the beginning of his rule, he was a reformist, building on the work of Gregory VII, making decisions that were fundamental for the nascent religious movements, rebuilding papal authority and restoring its financial position. It was at his most notable council at Clermont in November 1095 he arranged the juristic foundation of the crusading movement with two of its recorded directives: the remission of all atonement for those who journeyed to Jerusalem to free the church and the protection of all their goods and property while doing it. His subsequent call to arms led to the first crusading expedition, but he died in July 1099 without knowing that two weeks earlier Jerusalem had been captured.[27]

The description and interpretation of crusading began with accounts of the First Crusade. The image and morality of earlier expeditions propagandised for new campaigns.[28] The understanding of the crusades was based on a limited set of interrelated texts. Gesta Francorum or Exploits of the Franks created a papalist, northern French and Benedictine template for later works that had a degree of martial advocacy attributing both success and failure to God's will.[29] This clerical view was challenged by vernacular adventure stories based on the work of Albert of Aachen. William of Tyre expanded Albert's writing in his Historia he completed by 1200, describing the warrior state the Outremer became as a result of the tension between the providential and secular.[30] Medieval crusade historiography predominately remained interested in moralistic lessons, extolling the crusades as moral exemplars and cultural norms.[31]

Development of Chivalry

Chivalry defined the ideas and values of knights, who were central to the crusade movement. Militia was the original Latin term for army and milites for its members. Although literature illustrated prestige of knighthood, it was distinct from the aristocracy with 11th and 12th century texts depicting a class of knights close peasants in status. Until the 13th knighthood was not analogous with nobility and the knighthood was not a social class or legal status. Where before anyone could be a knight, it became increasingly closed to non-nobles. Knighthood became an honour and a grade of nobility.[32]

Its development related to a society founded upon the possession of castles; the milites, who defended these became knights and adopted a new form of combat involving the lance ideally suited for short cavalry charges. This technique supported the birth of chivalry which began developing codes, ethics and ideology. In order to combat the defensive armour was developed replacing coats of mail. Contraryto the representaion in the romances, battles were a relatively rare. Instead raids and sieges predominated in which knights played a minimal role. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries the probable ratio was one knight to seven to twelve infantry, mounted sergeants, and squires.[33]

Knighthood required a significant amount of combat training. This created a solidarity and gave rise to a sporting aspects of knightly combat: killing opponents was not the objective, instead capturing to win weapons, armour, horses, or ransom. In this way a moral code grew out of economic necessity and incorporated social, and religious dimensions. Ransom raised considerable sums such as 150,000 silver marks for Richard the Lionheart who was captured returning from the Holy Land and 200,000 livres for King Louis IX of France captured by the Muslims of Egypt. Ransom for lesser knights was much less, sometimes amounting only to their equipment. Foot soldiers were excluded from this, often killed without shame, leading to the ethic that defeated knights should be spared. From the 12th century tournaments provided knights with practice, sport, wealth, glory, patronage and provided public entertainment.[34]

Vernacular literature glorified ideas of adventure and virtues of valour, largesse, and courtesy. This created an ideal of the perfect knight as a cultural exemplar. Chivalry was a way of life, a social and moral model which evolved into a myth that conflicted with the ideals of the church. While fearing the knighthood the church co-opted it in conflicts with feudal lords. Those who fought for the church were praised, others were excommunicated. By the 11th century the church developed liturgical blessings sanctifying new knights and existing literary themes, such as the legend of the Grail were christianised and treatises on chivalry written.[35]

Crusading and chivalry were wedded as the former was effectively pilgrimage and holy war. The sanctification of war developed during the 11th century through campaigns fought for, instigated or blessed by the pope including Norman conquest of Sicily, the recovery of Iberia from the Muslims, and the Pisan and Genoese Mahdia campaign of 1087 to North Africa. Crusading followed this tradition, assimilatating chivalry within the locus of the church through:

- The concept of pilgrimage, the primary focus in Pope Urban II’s call to crusade.

- The remission of sin that for knights for the killing of adverseries became a penance of itself, therefore not requiring further penance.

- The identification of Muslims as pagans, making those killed by them martyrs equivalent to early Christian victims of pagan persecution

- The identification of the recovery of the despoiled country of Christ. Urban assembled his own army to re-establish the patrimony of Christ over the heads of kings and princes.

- The principle that crusade knights were Christ’s vassals or milites Christi. This refined the term used originally for Christians, then only clergy and monks fighting evil through prayer, from 1075 warriors fighting for St Peter before becoming synonymous with crusader. Knights no longer needed to abandon their way of life or become monks to achieve salvation. Crusading was a break with chivalry, Urban II denounced war among Christians as sinful but fighting for Jerusalem, led by a new knighthood as meritorious and holy. This ideology did not support chivalry, only crusading.[36]

The First Crusade was a military success, but a papal failure. Urban initiated a Christian movement seen as pious and deserving but not fundamental to the concept of knighthood. Crusading did not become a duty or a moral obligation like pilgrimage to Mecca or Jihad were to Islam. It remained secular and the creation of military religious orders is indicative of this failure. The milites Christi became orders of monks called to take up the sword and to shed blood. This was a doctrinal revolution within the church regarding warfare. Its acknowledgement in 1229 at the Council of Troyes integrated the concept holy war into the doctrines of the Latin Church. It illustrated the failure of the church to assemble a force of knights from the laity and the ideological split between crusades and chivalry.[37]

Paschal II, Calixtus II and the early 12th century

A monk called Rainerius followed Urban, taking the name Paschal II, and it has he who sent congratulations to Outremer over the success of the First Crusade. While he defeated the three anti-popes that followed Clement III and ended the schism in the papacy, he became embroiled in conflict with Henry V, the Holy Roman Emperor and church reformists led by his eventual successor Guy, archbishop of Vienne (later Pope Calixtus II) over the right to invest bishops. Faced with a revolt of the reformers he revoked concessions he had made to the emperor. His legislation developed that of his predecessors in connection with crusading. After the failed 1101 crusade, he supported Bohemund I of Antioch's gathering of another army with the flag of St. Peter and a cardinal legate, Bruno of Segni. Relations were fraught between the Latin patriarchate and monarchy of Jerusalem. Paschal organised the Palestine church through three legations led by Maurice of Porto in 1100, Ghibbelin of Arles in 1107 and Berengar of Orange in 1115. By confirming Urban's ruling that the churches in territory won would be held by the successful princes, Paschal ensured ecclesiastical and political borders coincided and settled the dispute between Jerusalem and Antioch over the archbishopric of Tyre.[38]

Calixtus II played a significant role in extending the definition of crusading in his five years as Pope preceding his death in 1124. Named Guy, he was one of the six sons of William I, Count of Burgundy and a distant relation to Baldwin II of Jerusalem. Three of his brothers died taking part in the crusade of 1101. The truce he engineered between Emperor Henry V and the papacy through ratifying the Concordat of Worms at the First Lateran Council in 1123 was the pinnacle of his reign. The council also extended the decrees of Urban II and Paschal II promising remission of sin and protection for property and family for crusaders. Additionally, addition he equated the reconquest of Iberia from the Muslims with the crusading to the Holy Land leading posthumously to the campaign by King Alfonso I of Aragon against Granada in 1125.[39]

Development of the Military orders

The crusaders' propensity to follow the customs of their Western European homelands meant that there were very few innovations developed from the culture in the crusader states. Three notable exceptions to this are the military orders, warfare and fortifications.[40] The Knights Hospitaller, formally the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, were founded in Jerusalem before the First Crusade but added a martial element to their ongoing medical functions to become a much larger military order.[41] In this way, the knighthood entered the previously monastic and ecclesiastical sphere.[42]

Military orders like the Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar provided Latin Christendom's first professional armies to support the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other crusader states. The Templars, formally the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, and their Temple of Solomon were founded around 1119 by a small band of knights who dedicated themselves to protecting pilgrims en route to Jerusalem.[43] The Hospitallers and the Templars became supranational organisations as papal support led to rich donations of land and revenue across Europe. This led to a steady flow of recruits and the wealth to maintain multiple fortifications in the crusader states. In time, they developed into autonomous powers in the region.[44] After the fall of Acre, the Hospitallers relocated to Cyprus, then conquered and ruled Rhodes (1309–1522) and Malta (1530–1798), and continue in existence to the present-day. King Philip IV of France probably had financial and political reasons to oppose the Knights Templar, which led to him exerting pressure on Pope Clement V. The pope responded in 1312, with a series of papal bulls including Vox in excelso and Ad providam that dissolved the order on the alleged and probably false grounds of sodomy, magic and heresy.[45]

Eugenius III and the later 12th century

The Pisan noble Bernard Pignatelli became Pope in 1145 in succession to Lucius II, taking the name Eugenius III. He was influenced by Bernard of Clairvaux to join the Cistercian. Exiled by antipapal commune he encouraged King Louis VII and the French to defend Edessa from the Muslims with bull Quantum predecessores in 1145 and again, slightly amended, in 1146. He clarified Urban's ambiguous position with the view that the crusading indulgence was remission from God's punishment for sin, as opposed to only remitting ecclesiastical confessional discipline. Eugenius commissioned Bernard of Clairvaux to the crusade and travelled to France where he issued Divini dispensatione (II), under the influence of Bernard, associating attacks on the Wends and the reconquest of Spain. The crusade in the East was not a success and he subsequently resisted further crusading. King Roger II of Sicily enabled his return to Rome in 1149 but he fled Roman politics again until Emperor Frederick Barbarossa enabled his return shortly before his death in 1153.[46]

13th century

Elected pope in 1198, Innocent III reshaped the ideology and practice of crusading. He emphasised crusader oaths and penitence, and clarified that the absolution of sins was a gift from God, rather than a reward for the crusaders' sufferings. Taxation to fund crusading was introduced and donation encouraged.[47][48] In 1199 he was the first pope to deploy the conceptual and legal apparatus developed for crusading to enforce papal rights. With his 1213 bull Quia maior he appealed to all Christians, not just the nobility, offering the possibility of vow redemption without crusading. This set a precedent for trading in spiritual rewards, a practice that scandalised devout Christians and later became one of the causes of the 16th-century Protestant Reformation.[49][50] From the 1220s crusader privileges were regularly granted to those who fought against heretics, schismatics or Christians the papacy considered non-conformist.[51] When Frederick II's army threatened Rome, Gregory IX used crusading terminology. Rome was seen as the Patrimony of Saint Peter, and canon law regarded crusades as defensive wars to protect theoretical Christian territory.[52]

As papal-imperial legate between 1217 and 1221, Cardinal Hugo Ugolino of Segni preached the Fifth Crusade in northern Italy obstructed by emperor Frederick II's delayed departures. When he became Pope Gregory IX in 1227 he invoked Frederick's suspended excommunication for this. Frederick gained Christian access to Jerusalem through negotiation, but his excommunicate status and spousal claims to the kingdom divided the Outremer. On his return Frederick defeated Gregory IX's invasion of Sicily. Gregory condemned the settlement in Jerusalem but used the peace to develop the wider crusading movement. The Albigensian Crusade ended successfully in 1229, the mendicant orders organised anti-heretical inquisitions, crusade recruitment expanded, missionary work was undertaken, negotiation entered with the Greek church and the Dominican Order to channel aid and privileges to the Teutonic Order. For the first time a pope used full application of crusading indulgences, privileges, and taxes against the emperor and commutation of crusader vows were transferred from expeditions to Outremer to other expeditions seen as supportive of the Holy Land. These measures and the use clerical income tax for fighting the emperor led to the full development of political crusades by Gregory's successor, Innocent IV. Frederick besieged Rome after conflict in Lombardy and Sardinia during which Gregory in 1241.[53]

Innocent IV rationalised crusading ideology on the basis of the Christians' right to ownership. He acknowledged Muslims' land ownership, but emphasised that this was subject to Christ's authority.[54] Rainald of Segni, who was elected pope in December 1254 taking the name Alexander IV, continued the policies of Gregory IX and Innocent IV. This meant supporting crusades against the Staufen dynasty, the North African Moors and pagans in Finland and the Baltic region. He attempted to gift Sicily to Edmund Crouchback, son of King Henry III of England, in return for a campaign to win it from Manfred, King of Sicily, son of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor but this was logistically impossible and the campaigns unsuccessful. He offered in negotiations with Theodore II Laskaris, the Greek emperor of Nicaea, the surrender of Latin-held Constantinople and restoration of the Greek Orthodox patriarchate in return for acknowledgment of papal supremacy and the reunion of the Greek and Latin churches. But Theodore died in 1258 and his successor Michael VIII Palaiologos regained Constantinople anyway. Alexander's attempts failed in forming a league to confront the Mongols in the East or the invasion of Poland and Lithuania. Frequent crusade calls to fight in eastern Europe (1253–1254, 1259) and Outremer (1260–1261) prompted small forces but his death prevented a general passage.[55]

Later Crusading Movement

At the end of the 13th century the impending Mamluk victory in the Holy Land left the movement in crisis. Success in Spain, Prussia, and Italy did not compensate for losing the Holy Land. This was a crisis of faith as well as military strategy that the Second Council of Lyon considered religiously shameful. The crisis did not end with the final fall of the Outremer in 1291 as general opinion did not consider that final. It was only when the Hundred Years' War began in 1337 that recovery hopes faded. However, ideas, and the consolidation of methods of organization and finance following the Council and spanning the decades around 1300 demonstrated qualities of engagement, resilience, and adaptability which in part enabled the movement's survival for generations.[56] The near three-year period between the death of Pope Clement IV and the election of Tedaldo Visconti as Pope Gregory X in 1271 was the longest interregnum between Popes. The defeat of the Staufen emperors by his predecessors left Gregory free to work towards reunification of the Greek and Latin churches. He viewed this as necessary for a new crusade and the protection of Outremer. The Lyon council opened in May 1274, where he demanded that the Orthodox delegation accept all Latin teaching. The primary Byzantine motivation was preventing Western attacks and Gregory reversed papal support for Charles I of Anjou, king of Sicily. European conflict lessened monarchical interest in joining crusades ending his crusade plans.[57]

Even then there were more than twenty treatises on the recovery of the Holy Land between the councils of Lyon in 1274 and Vienna in 1314 prompted by Gregory X and his successors following the example of Innocent III in requesting advice. This advice led to plans for a blockade of the Mamluks, a passigium particulare that provided a bridgehead and a passigium generale by a professional army to follow. Details were debated through the prism of Capetian and Aragonese dynastic politics. Short lived popular crusading broke out every decade, such as those prompted by the Mongol victory over the Mamluks at Homs and popular crusades in France and Germany. The papacy's institutionalisation of taxation to pay for professional crusading armies on a contractual basis was an extraordinary achievement despite numerous challenges, including a six-year tenth levied on clerical incomes.[58]

Commencing in 1332 the numerous Holy Leagues were a new manifestation of the movement in the form of temporary alliances between interested Christian powers. Successful campaigns included the capture of Smyrna in 1344, at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 and the recovery of territory in the Balkans between 1684 and 1697.[59] After the Treaty of Brétigny between Enland and France, the anarchic political situation in Italy prompted the curia to begin issuing indulgences for those who would fight the Routiers threatening the Pope and his court at Avignon. In 1378 the papacy split into two and then three rival papacies with rival Popes declaring crusades against each other. The growing threat from the Ottoman Turks provided a welcome distraction that could unite the papacy and divert the violance to another front.[60]

The Venetian, Gabriel Condulmaro, succeeded to Martin V as Eugenius IV in 1431, contributing the policy of ecumenical negotiation with the Byzantines. The visit of Emperor John V Palaiologos, the patriarch of Constantinople and 700 supporters to Ferrara for an ecumenical almost bankrupted him in combination with a revolt in Rome. In 1439 the council moved to Florence, and proclaimed union of the Latin, Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Nestorian, and Cypriot Maronite churches. The Byzantine reward was military support, but the crusade of 1444 was defeated at Varna in Bulgaria and achieved little. The Council of Basel deposed him in 1439 in favour of Felix V but the council lost support and Eugenius continued his policies until his death in 1447.[61]

Humanist Enea Silvio became pope as Pope Pius II in 1458. Constantinople had fallen to the Ottomans in 1453; its recovery was the primary focus of his pontificate. The Congress of Mantua was an unsuccessful blending them with humanist style and thought attempt to create a European alliance, even though Pius promised to personally participate in the expedition. His famous Latin letters and speeches at Mantua at the Diets of Regensburg and Frankfurt became models of their genre blending humanist styles and thought with Pope Urban II's sermon at Clermont, the First Crusade, the chronicle of Robert of Rheims and Bernard of Clairvaux's letter of exhortation. Besides this he also advised the conquerer of Constantinople to convert to Christianity and become a second Constantine.[62]

Rodrigo Borja, who became pope as Pope Alexander VI in 1492, attempted to reignite crusading to counter the threat of the Ottoman Empire, but his secular ambitions for his son Cesare and objective to prevent King Charles VIII of France conquering Naples was paramount. He founded the League of Venice with the Sforza, Republic of Venice, Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor and the Spanish to fight the French but his attempts to organise crusading against the Turks came to nothing. The sale of indulgences gained large sums but there was opposition to the clerical tithes and other fund raising to support mercenary crusading armies on the grounds that these were being used for papal causes in Italy and appropriated by secular rulers. Charles VIII's invasion plans prevented the organisation a crusade by Hungary, Bohemia, and Maximilian in 1493 leading to Italo-Turkish alliances. Marino Sanuto the Younger, Stephen Teglatius and Alexander himself in Inter caetera wrote of the continued commitment to crusading, the organisational issues, theory, the impact of the Spanish Reconquista completed with the capture of Granada in 1492, the defence and expansion of the faith, and partitioning northern Africa and the Americas between Portugal and Spain the conquest of which he granted crusading privileges and funding.[63] Around the end of the 15th century the military orders were transformed. Castlie nationalised its orders between 1487 and 1499. The Hospitallers were expelled from Rhodes in 1523 and the Prussion Teutonic Order secularised in 1523.[64]

In the 16th century the rivalry between Catholic monarchs prevented anti-Protestant crusades but individual military actions were rewarded with crusader privileges, including Irish Catholic rebellions against English Protestant rule and the Spanish Armada's attack on Queen Elizabeth I and England.[65] Political concerns provoked self-interested polemics that mixed the legendary and evidential past. Humanist scholarship and theological hostility created an independent historiography. The rise of the Ottomans, the French Wars of Religion, and the Protestant Reformation encouraged the study of crusading. Redemptive solutions were sought in the military and spiritually penitent traditionalist wars of the cross while some—such as English martyrologist John Foxe—saw these as examples of papist superstition, corruption of religion, papal idolatry and profanation. The Roman church was blamed for the failure of the crusades. War against the infidel was laudable, but not crusading based on doctrines of papal power, indulgences and against Christian religious dissidents, such as the Albigensian and Waldensians. Some Roman Catholic writers considered the crusades gave precedents for dealing with heretics. Both strands thought the crusaders were sincere and were increasingly uneasy in considering war a religious exercise as opposed of having a territorial objective. This secularisation was based on juristic ideas of just war that Lutherans, Calvinists and Roman Catholics could all subscribe and the role of Indulgences diminished in Roman Catholics tracts on the Turkish wars. Alberico Gentili and Hugo Grotius developed secular international laws of war that discounted religion as a legitimate cause contrasting to popes, who persisted in issuing crusade bulls for generations.[66] Lutheran scholar Matthäus Dresser developed Foxe, viewing crusaders as credulous, misled by popes and profane monks, with conflicting temporal and spiritual motivation. For him,papal policy mixed with self-interest and the ecclesiastical manipulation of popular piety and he emphasised the great deeds by those who could be considered as German, such as Godfrey of Bouillon.[67] Crusaders were lauded for their faith, but Urban II's motivation was associated with conflict with German Emperor Henry IV. Crusading was flawed, and ideas of restoring the physical Holy Places detestable superstition.[68] Pasquier highlighted the failures of the crusades and the damage that religious conflict had inflicted on France and the church, listing victims of papal aggression, sale of indulgences, church abuses, corruption, and conflicts at home.[69] Dresser's nationalist view enabled the creation by non–Roman Catholic scholars of a wider cultural bridge between the papist past and Protestant future. This formed a sense of national identity for secular Europeans across the confessional divide. Textual scholars such as Reinier Reineck, French Calvinist diplomat Jacques Bongars and Marino Sanudo Torsello established two dominant themes for crusade study: firstly intellectual or religious disdain, and secondly national or cultural admiration. Crusading now had only a technical impact on contemporary wars but provided imagery of noble and lost causes such as William Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part II and Torquato Tasso's reinvention of Godfrey and the First Crusade as a romance of love, magic, valour, loyalty, honour, and chivalry. In the 17th century Thomas Fuller maintained moral and religious disapproval and Louis Maimbourg embodied national pride. Both took crusading beyond the judgment of religion, and this secularised vision increasingly depicted crusades in good stories or as edifying or repulsive models of the distant past.[70]

Later Historiography

in the 18th century, Age of Enlightenment philosopher historians narrowed the chronological and geographical scope of crusading to the Levant and the Outremer and the historical period to between 1095 and 1291. Attempts were made to number crusades at eight and sometimes five—1096–1099, 1147–1149,1189–1192, 1217–1229 and 1248–1254.Without an Ottoman threat, influential writers such as Denis Diderot, Voltaire, David Hume and Edward Gibbon considered crusading in terms of anticlericalism with disdain for the apparent ignorance, fanaticism, and violence.[71] For them crusading was a conceptual tool to critique religion, civilisation and cultural mores. By the 19th century some considered this view as unnecessarily hostile and ignorant.[72] The debate foreshadowed ideas that the conflict between Christianity and Islam was part of the World's Debate in which the West won, not Christianity. Interest was on the cultural values, motives and behaviour of the crusaders as opposed to their failure. Napoleon's Egypt and Syria campaign from 1798–1799 increased the French view that the Holy Land was the prime concern.[73] Alternatively, for Rationalists the crusades were a stage in the improvement of European Civilisation.[74] In France, the idea evolved that the crusades were an important part of national history and identity. Academic circles used the phrase Holy War, but more neutral terms kreuzzug and croisade became established. The word crusade entered the English language in the 18th century as a hybrid from Spanish, French and Latin.[75] Increasingly positive views of the Middle Ages developed placing crusading in a narrative of progress towards modernity. Walter Scott's novels Ivanhoe and The Talisman and Charles Mills' History of the Crusades demonstrated admiration of crusading ideology and violence. In a world of unsettling change and rapid industrialisation nostalgics, escapist apologists and popular historians developed a positive view of crusading.[73] Jonathan Riley-Smith considers that much of the popular understanding of the crusades derives from the 19th century novels of Scott and the histories by Joseph François Michaud. Admiration was married with supremacist triumphalism and supported nascent European commercial and political colonialism in the Near East. A benevolent Franco-Syrian society in Outremer was describedattractively during the French mandates in Syria and Lebanon that were considered La France du Levant or France in the Levant. The kingdom of Jerusalem was seen as the first attempt by Franks of the West to found colonies.[76] After World War I crusading was viewed less positively responses; war was sometimes necessary but not good, sanctified, or redemptive.[76] The crusades had aroused little interest among Islamic and Arabic scholars until the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the penetration of European power. The Jerusalem visit in 1898 of Kaiser Wilhelm prompted further interest, and the first Arabic history of the crusades.[77] The definition of the crusade remains contentious, although the view that the crusades to the East were the most prestigious and provided the scale against which the others were measuredis largely accepted. There is disagreement whether it is only those campaigns launched to recover or protect Jerusalem that are proper crusades. Crusading only became a coherent paradigm around 1200. It was the result of an ecclesiastical initiative, but also a submission by the church to secular militarism and militancy by the early 13th century. Today, Crusade historians study the Baltic, the Mediterranean, the Near East, even the Atlantic, and crusading's position in, and derivation, from host and victim societies. Chronological horizons have crusades existing into the early modern world e.g. the survival of the Order of St. John on Malta until 1798.[78] Academic study of crusading in the West is now integrated into the mainstream study of theology, the Church, law, popular religion, aristocratic society and values, and politics. The Muslim context now receives attention from Islamicists. Disdain has been replaced by attempts to locate crusading within its social, cultural, intellectual, economic, and political context. Crusader historians employ wider ranges of evidence, including charters, archaeology, and the visual arts, to supplement chronicles and letters. Local studies have lent precision as well as diversity.[78]

Contemporary Reception

Criticism

There is evidence of criticism of crusading and the behaviour of crusaders from the beginning of the movement. Although few challenged the concept in the 12th and 13th centuries, there were vociferous objections to crusades against heretics and Christian lay powers. The Fourth Crusade's attack on Constantinople and the use of resources against enemies of the church in Europe, the Albigensian heretics and Hohenstaufen, were all denounced. Troubadours ctiticised expeditions in southern France regretting the neglect of the Holy Land. The behaviour of combatants was seen as inconsistent with that expected of soldiers in a holy war. Chroniclers and preachers complained of sexual promiscuity, avarice, and overconfidence. Failures in the First Crusade, the Hattin and of entire campaigns was blamed on human sin. Gerhoh of Reichersberg connected that of the Second Crusade to the coming of the Antichrist. Remediation included penitential marches, reformation requests, prohibitions of gambling and luxuries, and limits on the number of women were attempted in. The Würzburg Annals criticised the behaviour of the crusaders and suggested it was the devil's work. Louis IX of France's defeat at the battle of Mansurah provoked doubt and challenge to crusading in sermons and treatises, such as Humbert of Romans's De praedicatione crucis (The preaching of the cross). The cost of armies led to taxation, an idea attacked as an unwelcome precedent by Roger Wendover, Matthew Paris; and Walther von der Vogelweide. Concern was expressed of the Franciscan and Dominican friars abusing the system of vow redemption for financial gain. Some saw the peaceful conversion of Muslims as the best option, but there is no evidence that this represented public opinion and the continuation of crusading indicates the opposite. At the Second Council of Lyons in 1274, Bruno von Schauenburg, Humbert, Gilbert of Tournai and William of Tripoli produced treatises articulating the change required for success. Despite criticism, crusading appears to have maintained popular appeal with recruits continuing to take the cross from a wide geographical area.[79]

Medieval literature

There exists greater than fifty texts in Middle English and Middle Scots from around 1225 to 1500 with Crusading themes. These were usually performed to an audience, as opposed to read, for entertainment and as propaganda for a political and religious identity, differentiating the Christian "us" and the non-Christian "other." The works include romances, travelogues such as Mandeville's Travels, poems such as William Langland's Piers Plowman and John Gower's Confessio Amantis, the Hereford Map and the works of by Geoffrey Chaucer. Many were written after crusading fervour had diminished demonstrating a continuing interest. Chivalric Christendom is depicted as victorious and superior, holding the spiritual and moral high ground. They mainly originating from translated French originals and adaptations. Some, like Guy of Warwick used the portrayal of Muslim leaders as analogies to criticise contemporary politics. Popular motifs include chivalrous Christian knights seeking adventure and fighting Muslim giants or a king traveling in disguise such as Charlemagne in the Scots Taill of Rauf Coilyear. In crusading literature legendary figures are endowed with military and moral authority with Charlemagne portrayed as a role model, famed for his victories over the pagan Saxons and Vikings, his religious fervour marked by forced conversion. The entertainment aspect plays a vital role encouraging an element of "Saracen bashing". The literature demonstrates populist religious hatred and bigotry, in part because Muslims and Christians were economic, political, military, and religious rivals while exhibiting a popular curiosity about and fascination with the "Saracens".[80]

Song

Propaganda

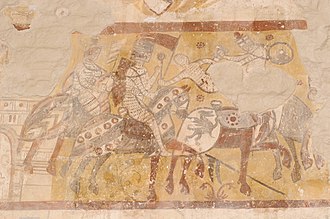

For recruitment purposes, Popes marked the initiation of each crusade by public preaching of its aims, spiritual values and justifications. Preaching could be authorised and unofficial. The news cascaded through the church hierarchy in writing in a Papal bull, although this system was not always reliable because of conflicts among clerics, local political concerns and lack of education. From the 12th century, the Cistercian Order was used for propaganda campaigns; the Dominicans and Franciscans followed in the 13th century. Mendicant friars and papal legates targeted geographies. After 1200, this sophisticated propaganda system was a prerequisite for the success of multiple concurrent crusades. The message varied, but the aims of papal control of the toll of crusading remained. Holy Land crusades were preached across Europe, but smaller ventures such as the Northern and Italian crusades were preached only locally to avoid conflict in recruitment. Papal authority was critical for the effectiveness of the indulgence and the validity of vow redemptions. Aristocratic culture, family networks and feudal hierarchies spread informal propaganda, often by word of mouth. Courts and tournaments were arenas where stories, songs, poems, news, and information about crusades were spread. Songs of the crusades became increasingly popular, although some troubadours were hostile after the Albigensian Crusade. Chivalric virtues of heroism, leadership, martial prowess, and religious fervour were exemplars. Visual representations in books, churches and palaces served the same purpose. Themes were expanded in church art and architecture in the form of murals, stained glass windows, and sculptures. This can be seen in the windows at the abbey of Saint-Denis, many churches modelled on the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem, or murals commissioned by Henry III of England.[81]

Finance of Crusades

At first, crusaders self-funded the arms and supplies required for their campaigns. Non-combatants probably hoped to join the retinues of the lords and knights augmenting their resources with forage and plunder. Leaders seeking to maintain armies employed many fighters as virtual mercenaries. Fleets and contingents would organise communally to share financial risk. When the nature of crusading changed with transportation shifting from land to sea, there were fewer non-combatants and systems of finance developed. Tallage was imposed on Jews, townsmen and peasants and levies on secular and ecclesiastical vassals. This developed into formal taxation, including the Saladin Tithe in 1188. By the 13th century, the papacy's taxation of the church dwarfed secular contributions. There were serious protests when this revenue was transferred to theatres other than the Holy Land, or to secular rulers for other purposes. While actual methods varied, significant improvements were made in accounting and administration, although this did not prevent resistance, delay, and diversion of funds. In time, the military orders and Italian banks replaced the Curia in the crusade banking system. Secular taxation developed from this, and with the crusades becoming entwined with dynastic politics, led to resentment. Gifts, legacies, confiscations from heretics, donations deposited in chests placed in local churches, alms, and the redemption of crusading vows provided funding. Some of these caused significant criticism, and Innocent III warned bishops to avoid extortion and bribery. Full plenary indulgences became confused with partial ones when the practice of commuting vows to crusade into monetary donations developed.[82]

Women

Women accompanied crusade armies, supported society in the crusader states, and guarded crusaders' interests in the west. Margaret of Beverley's brother Thomas of Froidmont wrote a first-person account of her adventures, including fighting at the siege of Jerusalem in 1187, and two incidents of capture and ransom. However, women rarely feature in the surviving sources, because of the legal and social restrictions on them. Crusading was defined as a military activity, and warfare was considered a male pursuit. Women were discouraged from taking part but could not be banned from what was a form of pilgrimage. Most women in the sources are noble spouses of crusaders.[83][84]

Sources that refer to the motivation of women indicate the same spiritual incentives, church patronage, and involvement in monastic reform and heretical movements. Female pilgrimage was popular and crusading enabled this for some women. Medieval literature illustrates unlikely romantic stereotypes of armed female warriors, while eyewitness Muslim sources recount tales of female Frankish warriors, but these are likely mocking the perceived weakness or barbarity of the enemy. Women probably fought, but chroniclers emphasised only in the absence of male warriors. Noblewomen were considered feudal lords if they had retinues of their own knights. They were often victims and regarded as booty. Lower-class women performed mundane duties such as bringing provision, encouragement, washing clothes, lice picking, grinding corn, maintaining markets for fish and vegetables, and tending the sick. They were associated with prostitution, causing concern of the perceived link between sin and military failure. Sexual relations with indigenous Muslims and Jews were regarded as a sin that would lead to divine retribution. Medieval historians emphasised the crusaders purified the Holy Places through widespread slaughter of men, women, and children. Sexual activity naturally led to pregnancy and its associated risks. Noblewomen were seldom criticised for their dutiful provision of heirs, but in the lower ranks pregnancy attracted criticism of the unmarried leading to punishment. Even the harshest of critics recognised woman were essential for a permanent Christian population, but apparently most female crusaders returned home after fulfilling their pilgrimage vows. Frankish rulers in the Levant intermarried with western European nobility, the local Armenian, and the Byzantine Christian population for political reasons. Continual warfare created a constant lack of manpower, and lands and titles were often inherited by widows and daughters who were offered in the West as favourable marriages. Bridegrooms brought entourages to secure their new domain, often causing friction with the established baronage.[85]

The women left behind were impacted in several ways. The church pledged protection of property and families, but crusaders left charters including provision for their female relatives, money, or endowments to religious houses. There were concerns regarding adultery, which meant a wife could theoretically prevent her husband from crusading. Wives were described as inhibiting crusaders, but there is little hard evidence. Patterns of intermarriage in France suggest that certain marriage alliances transmitted traditions of crusading between families, encouraging the crusade ideal through the early religious education of children and employing supportive chaplains. Popes encouraged women to donate money or sponsorship instead of crusading, in return for the same spiritual benefits. This addressed the issue of non-combatants and raised funds directly or through monastic houses, including the military orders. Charters demonstrate crusaders sold or mortgaged land to female relatives or engaged in transactions where their consent was required. Without evidence it was impossible to know whether crusaders were alive or dead, so woman in the West could not remarry for between five and 100 years.[86]

Legacy

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was the first experiment in European colonialism, setting up the Outremer as a "Europe Overseas". The raising, transportation, and supply of large armies led to a flourishing trade between Europe and the Outremer. The Italian city-states of Genoa and Venice flourished, planting profitable trading colonies in the eastern Mediterranean.[87] The crusades consolidated the papal leadership of the Latin Church, reinforcing the link between Western Christendom, feudalism, and militarism, and increased the tolerance of the clergy for violence.[45] Muslim libraries contained classical Greek and Roman texts that allowed Europe to rediscover pre-Christian philosophy, science and medicine.[88] The growth of the system of indulgences became a catalyst for the Reformation in the early 16th century.[89] The crusades also had a role in the formation and institutionalisation of the military and the Dominican orders as well as of the Medieval Inquisition.[90]

The behaviour of the crusaders in the eastern Mediterranean area appalled the Greeks and Muslims, creating a lasting barrier between the Latin world and the Islamic and Orthodox religions. This became an obstacle to the reunification of the Christian church and fostered a perception of Westerners as defeated aggressors.[45] Many historians argue that the interaction between the western Christian and Islamic cultures played a significant, ultimately positive, part in the development of European civilisation and the Renaissance.[91] Relations between Europeans and the Islamic world stretched across the entire length of the Mediterranean Sea, leading to an improved perception of Islamic culture in the West. But this broad area of interaction also makes it difficult for historians to identify the specific sources of cultural cross-fertilisation.[92]

Historical parallelism and the tradition of drawing inspiration from the Middle Ages, have become keystones of political Islam encouraging ideas of a modern jihad and long struggle, while secular Arab nationalism highlights the role of Western imperialism.[77] Muslim thinkers, politicians and historians have drawn parallels between the crusades and modern political developments such as the mandates given to govern Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Israel by the United Nations.[93] Right-wing circles in the Western world have drawn opposing parallels, considering Christianity to be under an Islamic religious and demographic threat that is analogous to the situation at the time of the crusades. Crusader symbols and anti-Islamic rhetoric are presented as an appropriate response, even if only for propaganda. These symbols and rhetoric are used to provide a religious justification and inspiration for a struggle against a religious enemy.[94] Some historians, like Thomas F. Madden, argue that modern tensions result from a constructed view of the crusades created by colonial powers in the 19th century and transmitted into Arab nationalism. For him, the crusades are a medieval phenomenon in which the crusaders were engaged in a defensive war on behalf of their co-religionists.[95]

In 1936, the Spanish Catholic Church baptised and supported the coup of Francisco Franco, declaring a crusade against Marxism and atheism. Thirty-six years of National Catholicism followed during which the idea of Reconquista as a foundation of historical memory, celebration and Spanish national identity became entrenched in conservative circles. Reconquista lost its historiographical hegemony when democracy was restored in 1978, but it remains a fundamental definition of the medieval period within conservative sectors of academia, politics, and the media because of its strong ideological connotations.[96]

See also

Notes

- ^ Tyerman explains that "holy war" was the primary academic term from the early 16th century until the German term Kreuzzug ("war of the cross") and the French croisade became established. Regarding English usage, he writes: "Samuel Johnson's Dictionary (1755) includes four variants: crusade, crusado, croisade and croisado (the word used by Francis Bacon). 'Crusade', perhaps first coined in 1706, certainly in vogue by 1753 when it was used in the English translation of Voltaire's essay (published as History of the Crusades; the following year as part of The General History and State of Europe), was popularised through its use by Hume (1761) and Gibbon."[10]

References

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 36.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Maier 2006a, pp. 627–629.

- ^ Maier 2006a, pp. 629–630.

- ^ Maier 2006a, pp. 630–631.

- ^ Tyerman 2004, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, p. 40

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 259

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 480

- ^ a b Tyerman 2011, p. 77.

- ^ Determann 2008, p. 13

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 47–50

- ^ a b Davies 1997, p. 358

- ^ Constable 2001, p. 12

- ^ Riley-Smith 2009, p. 27

- ^ Lock 2006, pp. 255–256

- ^ Lock 2006, pp. 172–180

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 167

- ^ Constable 2001, pp. 12–15

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 225–226

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, pp. 30–38.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, p. 31.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 18–19, 289.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Blumenthal 2006, pp. 1214–1217.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, p. 582.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Flori 2006, p. 244.

- ^ Flori 2006, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Flori 2006, p. 245-246.

- ^ Flori 2006, p. 246-247.

- ^ Flori 2006, p. 247-248.

- ^ Flori 2006, p. 248.

- ^ Blumenthal 2006b, pp. 933–934.

- ^ Blumenthal 2006c, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Prawer 2001, p. 252

- ^ Asbridge 2012, p. 169

- ^ Prawer 2001, p. 253

- ^ Asbridge 2012, p. 168

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 169–170

- ^ a b c Davies 1997, p. 359

- ^ MacEvitt 2006a.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 235–237.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 524–525.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 533–535.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 336.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, pp. 195–198.

- ^ Bird 2006d, pp. 546–547.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Bird 2006c, p. 41.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 260.

- ^ MacEvitt 2006c.

- ^ Housley 1995, pp. 262–265.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 270.

- ^ MacEvitt 2006b.

- ^ Orth 2006, pp. 996–997.

- ^ Bird 2006b, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Luttrell 1995, pp. 378.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, pp. 582–583.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, p. 583.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 38–42.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 47–50.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, pp. 583–584.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, p. 584.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 79.

- ^ a b Tyerman 2006c, pp. 584–585.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 67.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 71.

- ^ a b Tyerman 2006c, p. 586.

- ^ a b Asbridge 2012, pp. 675–680

- ^ a b Tyerman 2006c, p. 587.

- ^ Siberry 2006, pp. 299–301.

- ^ Cordery 2006, pp. 399–403.

- ^ Maier 2006b, pp. 984–988.

- ^ Bird 2006, pp. 432–436.

- ^ Hodgson 2006, pp. 1285–1286.

- ^ Riley-Smith 2000, p. 107.

- ^ Hodgson 2006, pp. 1288–1289.

- ^ Hodgson 2006, pp. 1289–1290.

- ^ Housley 2006, pp. 152–154

- ^ Nicholson 2004, pp. 93–94

- ^ Housley 2006, pp. 147–149

- ^ Strayer 1992, p. 143

- ^ Nicholson 2004, p. 96

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 667–668

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 674–675

- ^ Koch 2017, p. 1

- ^ Madden 2013, pp. 204–205

- ^ García-Sanjuán 2018, p. 4

Bibliography

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-688-3.

- Bird, Jessalynn (2006b). "Alexander VI". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-C. ABC-CLIO. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Bird, Jessalynn (2006c). "Alexander IV". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-C. ABC-CLIO. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Bird, Jessalynn (2006). "Finance of Crusades". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. pp. 432–436. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Bird, Jessalynn (2006d). "Gregory IX, Pope (d. 1241)". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. pp. 546–547. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Blumenthal, Uta-Renate (2006). "Urban II". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. IV:Q-Z. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1214–1217. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Blumenthal, Uta-Renate (2006b). "Paschal II". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. III:K-O. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1214–1217. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Blumenthal, Uta-Renate (2006c). "Calixtus II". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-C. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1214–1217. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Constable, Giles (2001). "The Historiography of the Crusades". In Laiou, Angeliki E.; Mottahedeh, Roy P. (eds.). The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-88402-277-0. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Cordery, Leona (2006). "English and Scots Literature". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. pp. 399–403. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Davies, Norman (1997). Europe: A History. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6633-6.

- Determann, Jörg (2008). "The Crusades in Arabic Schoolbooks". Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations. 19 (2): 199–214. doi:10.1080/09596410801923949. ISSN 0959-6410. S2CID 143518665.

- Dickson, Gary (2006). "Popular Crusades". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. III:K-P. ABC-CLIO. pp. 975–979. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Flori, Jean (2006). "Chivalry". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-C. ABC-CLIO. pp. 244–248. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- García-Sanjuán, Alejandro (2018). "Rejecting al-Andalus, exalting the Reconquista: historical memory in contemporary Spain". Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies. 10 (1): 127–145. doi:10.1080/17546559.2016.1268263. S2CID 157964339.

- Hodgson, Natasha (2006). "Women". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. IV:R-Z. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1285–1291. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Housley, Norman (1995). "The Crusading Movement 1271-1700". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 260–294. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Housley, Norman (2006). Contesting the Crusades. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1189-8.

- Jaspert, Nikolas (2006). "Reconquista". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. IV:Q-Z. ABC-CLIO. pp. 432–1019. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Jotischky, Andrew (2004). Crusading and the Crusader States (1st ed.). Harlow: Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-41851-6.

- Koch, Ariel (2017). "The New Crusaders: Contemporary Extreme Right Symbolism and Rhetoric". Perspectives on Terrorism. 11 (5): 13–24. ISSN 2334-3745.

- Lock, Peter (2006). Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-39312-6.

- Luttrell, Anthony (1995). "The Military Orders, 1312–1798". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 326–364. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2013). The Concise History of the Crusades (Third ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-1576-4.

- Maier, Christoph T. (2006a). "Ideology". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. pp. 627–631. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Maier, Christoph T. (2006b). "Propaganda". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. III:K-P. ABC-CLIO. pp. 984–988. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- MacEvitt, Christopher (2006a). "Eugenius III". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. pp. 414–415. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- MacEvitt, Christopher (2006b). "Eugenius IV". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. p. 415. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- MacEvitt, Christopher (2006c). "Gregory X (1210–1276)". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. p. 547. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Nicholson, Helen (2004). The Crusades. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32685-1.

- Orth, Peter (2006). "Pius II (1405–1464)". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. pp. 966–9671. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Prawer, Joshua (2001). The Crusaders' Kingdom. Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-84212-224-2.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2000). The First Crusaders, 1095–1131. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64603-1.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005). The Crusades: A Short History (Second ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10128-7.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1995). "The Crusading Movement and Historians". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2009). What Were the Crusades?. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-22069-0.

- Routledge, Michael (1995). "Songs". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 326–364. ISBN 978-0-19-285428-5.

- Siberry, Elizabeth (2006). "Criticism of Crusading". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-C. ABC-CLIO. pp. 299–301. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Strayer, Joseph Reese (1992). The Albigensian Crusades. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06476-2.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2004). The Crusades: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280655-0.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02387-1.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006b). "Crusades against Christians". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-C. ABC-CLIO. pp. 325–329. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006c). "Historiography, Modern". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. pp. 582–587. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2011). The Debate on the Crusades, 1099–2010. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7320-5.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2019). The World of the Crusades. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21739-1.

- Urban, William L. (2006). "Baltic Crusades". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-C. ABC-CLIO. pp. 184–192. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

Further reading

- Cobb, Paul M. (2014). The Race for Paradise : an Islamic History of the Crusades. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Flori, Jean (2005). "Ideology and Motivations in the First Crusade". In Nicholson, Helen J. (ed.). Palgrave Advances in the Crusades. Palgrave Advances. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 15–36. doi:10.1057/9780230524095_2. ISBN 978-1-4039-1237-4.

- Jubb, M. (2005). "The Crusaders' Perceptions of their Opponents". In Nicholson, Helen J. (ed.). Palgrave Advances in the Crusades. Palgrave Advances. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780230524095_2.

- Kedar, Benjamin Z. (1998). "Crusade Historians and the Massacres of 1096". Jewish History. 12 (2): 11–31. doi:10.1007/BF02335496. S2CID 153734729.

- Kostick, Conor (2008). The Social Structure of the First Crusade. Brill.

- Latham, Andrew A. (2011). "Theorizing the Crusades: Identity, Institutions, and Religious War in Medieval Latin Christendom". International Studies Quarterly. 55 (1): 223–243. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00642.x. JSTOR 23019520.

- Maier, C. (2000). Crusade Propaganda and Ideology: Model Sermons for the Preaching of the Cross. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511496554. ISBN 978-0-521-59061-7.

- Polk, William R. (2018). Crusade and Jihad: The Thousand-Year War Between the Muslim World and the Global North. Yale University Press.

- Tyerman, C. J. (1995). "Were There Any Crusades in the Twelfth Century?". The English Historical Review. 110 (437). Oxford University Press: 553–5773. doi:10.1093/ehr/CX.437.553. JSTOR 23019520.