Pennsylvania Dutch

Logo in Pennsylvania Dutch: "We still speak the mother language". | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| United States, especially Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, West Virginia; Canada, especially Ontario (Kitchener, Waterloo, Cambridge, Markham, Stouffville and Pickering), smaller population in California | |

| Languages | |

| English (including Pennsylvania Dutch English), Pennsylvania German | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheran, Reformed, German Reformed, Catholic, Moravian, Church of the Brethren, Mennonite, Amish, Schwenkfelder, River Brethren, Yorker Brethren, Judaism, Pow-wow | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| German American, Swiss American, Italian American, French American |

The Pennsylvania Dutch (Pennsylvania German: Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch), translated from German to English as Pennsylvania Germans, are a cultural group formed by German immigrants settling in the state of Pennsylvania during the 18th and 19th centuries. These emigrated primarily from German-speaking territories of Europe, now partly within modern-day Germany (mainly from Palatinate, Baden-Württemberg, Hesse, and Rhineland), but also from the Netherlands, Switzerland and France's Alsace-Lorraine Region, traveling down the Rhine river to seaports.

The first settlers described themselves as Deitsch, corresponding with the German language Deutsch (for "German") later corrupted to "Dutch". They spoke numerous south German dialects, including Palatine. It was through their cross-dialogue interaction, the relative lack of new German immigrants from about 1770 to 1820, and what was retained by subsequent generations that a hybrid dialect emerged, known as Pennsylvania German (or Pennsylvania Dutch), which has resonance to this day.

The Pennsylvania Dutch maintained numerous religious affiliations, with the greatest number being Lutheran or German Reformed, but also many Anabaptists, including Mennonites, Amish, and Brethren. The Anabaptist groups espoused a simple lifestyle, and their adherents were known as Plain people (or Plain Dutch); this contrasted to the Fancy Dutch, who tended to assimilate more easily into the European American mainstream. By the late 1700s, other denominations were also represented in smaller numbers.[1]

Etymology

Contrary to popular belief, the word "Dutch" in "Pennsylvania Dutch" is not a mistranslation, but rather a corruption of the Pennsylvania German endonym Deitsch, which means "Pennsylvania Dutch / German" or "German".[2][3][4][5] Ultimately, the terms Deitsch, Dutch, Diets and Deutsch are all descendants of the Proto-Germanic word *þiudiskaz meaning "popular" or "of the people".[6] The continued use of "Pennsylvania Dutch" was strengthened by the Pennsylvania Dutch in the 19th century as a way of distinguishing themselves from later (post 1830) waves of German immigrants to the United States, with the Pennsylvania Dutch referring to themselves as Deitsche and to Germans as Deitschlenner (literally "Germany-ers", compare Deutschland-er) whom they saw as a related but distinct group.[7]

After the Second World War, use of Pennsylvania German virtually died out in favor of English, except among the more insular and tradition-bound Anabaptists, such as the Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonites. A number of German cultural practices continue to this day, and German Americans remain the largest ancestry group claimed in Pennsylvania by people in the census.[8]

Geography

The Pennsylvania Dutch live primarily in Southeastern and in Pennsylvania Dutch Country, a large area that includes South Central Pennsylvania, in the area stretching in an arc from Bethlehem and Allentown in the Lehigh Valley westward through Reading, Lebanon, and Lancaster to York and Chambersburg.[9] Some Pennsylvania Dutch live in the historically Pennsylvania Dutch-speaking areas of Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia's Shenandoah Valley.[10]

Palatinate of the Rhine immigrants

Many Pennsylvania Dutch were descendants of refugees who had left religious persecution in the Netherlands and the Palatinate of the German Rhine.[11] Of note were Amish and Mennonites who came to the Palatinate and surrounding areas from the German-speaking part of Switzerland, where, as Anabaptists, they were persecuted, and so their stay in the Palatinate was of limited duration.[12]

Most of the Pennsylvania Dutch have roots going much further back in the Palatinate. During the War of the Grand Alliance (1689–97), French troops pillaged the Palatinate, forcing many Germans to flee. The war began in 1688 as Louis XIV laid claim to the Electorate of the Palatinate. French forces devastated all major cities of the region, including Cologne. By 1697 the war came to a close with the Treaty of Ryswick, now Rijswijk in the Netherlands, and the Palatinate remained free of French control. However, by 1702, the War of the Spanish Succession began, lasting until 1713. French expansionism forced many Palatines to flee as refugees.[13]

Immigration to the United States

The devastation of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and the wars between the German principalities and France caused some of the immigration of Germans to America from the Rhine area. Members of this group founded the borough of Germantown, in northwest Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, in 1683.[14] They settled on land sold to them by William Penn. Germantown included not only Mennonites but also Quakers.[15]

This group of Mennonites was organized by Francis Daniel Pastorius, an agent for a land purchasing company based in Frankfurt am Main.[14] None of the Frankfurt Company ever came to Pennsylvania except Pastorius himself, but 13 Krefeld German (South Guelderish-speaking) Mennonite families arrived on October 6, 1683, in Philadelphia. They were joined by eight more Dutch-speaking families from Hamburg-Altona in 1700 and five German-speaking families from the Palatinate in 1707.[16]

In 1723, some 33 German Palatine families, dissatisfied under Governor Hunter's rule, migrated from Schoharie, New York, along the Susquehanna River to Tulpehocken, Berks County, Pennsylvania, where other Palatines had settled. They became farmers and used intensive German farming techniques that proved highly productive.[17]

Another wave of settlers from Germany, which would eventually coalesce to form a large part of the Pennsylvania Dutch, arrived between 1727 and 1775; some 65,000 Germans landed in Philadelphia in that era and others landed at other ports. Another wave from Germany arrived 1749–1754. Not all were Mennonites; some were Brethren or Quakers, for example.[18] The majority originated in what is today southwestern Germany, i.e., Rhineland-Palatinate[18] and Baden-Württemberg; other prominent groups were Alsatians, Dutch, French Huguenots (French Protestants), Moravians from Bohemia and Moravia and Germans from Switzerland. [19][20]

The Pennsylvania Dutch composed nearly half of the population of Pennsylvania and, except for the nonviolent Anabaptists, generally supported the Patriot cause in the American Revolution.[21] Henry Miller, an immigrant from Germany of Swiss ancestry, published an early German translation of the Declaration of Independence (1776) in his newspaper Philadelphische Staatsbote. Miller often wrote about Swiss history and myth, such as the William Tell legend, to provide a context for patriot support in the conflict with Britain.[22]

Frederick Muhlenberg (1750–1801), a Lutheran pastor, became a major patriot and politician, rising to be elected as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Migration to Canada

An early group, mainly from the Roxborough-Germantown area of Pennsylvania, emigrated to then colonial Nova Scotia in 1766 and founded the Township of Monckton, site of present day Moncton, New Brunswick. The extensive Steeves clan descends from this group.[23]

After the American Revolution, John Graves Simcoe, Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, invited Americans, including Mennonites and German Baptist Brethren, to settle in British North American territory and offered tracts of land to immigrant groups.[24][25] This resulted in communities of Pennsylvania Dutch speakers emigrating to Canada, many to the area called the German Company Tract, a subset of land within the Haldimand Tract, in the Township of Waterloo, which later became Waterloo County, Ontario.[26][27] Some still live in the area around Markham, Ontario[28][29] and particularly in the northern areas of the current Waterloo Region. Some members of the two communities formed the Markham-Waterloo Mennonite Conference. Today, the Pennsylvania Dutch language is mostly spoken by Old Order Mennonites.[30][26][31]

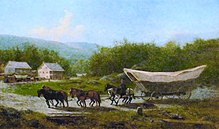

From 1800 to the 1830s, some Pennsylvania Dutch Mennonites in Upstate New York and Pennsylvania moved north to Canada, primarily to the area that would become Cambridge, Kitchener/Waterloo and St. Jacobs/Elmira in Waterloo County, Ontario plus the Listowel area adjacent to the northwest. Settlement started in 1800 by Joseph Schoerg and Samuel Betzner, Jr. (brothers-in-law), Mennonites, from Franklin County, Pennsylvania. Other settlers followed mostly from Pennsylvania typically by Conestoga wagons. Many of the pioneers arriving from Pennsylvania after November 1803 bought land in a 60,000 acre section established by a group of Mennonites from Lancaster County Pennsylvania, called the German Company Lands.[30][26]

Fewer of the Pennsylvania Dutch settled in what would later become the Greater Toronto Area in areas that would later be the towns of Altona, Ontario, Pickering, Ontario and especially Markham Village, Ontario and Stouffville, Ontario.[32] Peter Reesor and brother-in-law Abraham Stouffer were higher profile settlers in Markham and Stouffville.

William Berczy, a German entrepreneur and artist, had settled in upstate New York and in May 1794, he was able to obtain 64,000 acres in Markham Township, near the current city of Toronto. Berczy arrived with approximately 190 German families from Pennsylvania and settled here. Others later moved to other locations in the general area, including a hamlet they founded, German Mills, Ontario, named for its grist mill; that community is now called Thornhill, Ontario), in the township that is now part of York Region.[28][29]

Religion

Christianity

The immigrants of the 1600s and 1700s who were known as the Pennsylvania Dutch included Mennonites, Swiss Brethren (also called Mennonites by the locals) and Amish but also Anabaptist-Pietists such as German Baptist Brethren and those who belonged to German Lutheran or German Reformed Church congregations.[33][34] Other settlers of that era were of the Moravian Church while a few were Seventh Day Baptists.[35][36] Calvinist Palatines and several other denominations were also represented to a lesser extent.[37][38]

Over 60% of the immigrants who arrived in Pennsylvania from Germany or Switzerland in the 1700s and 1800s were Lutherans and they maintained good relations with those of the German Reformed Church.[39] The two groups founded Franklin College (now Franklin & Marshall College) in 1787.

Henry Muhlenberg (1711–1787) founded the Lutheran Church in America. He organized the Ministerium of Pennsylvania in 1748, set out the standard organizational format for new churches and helped shape Lutheran liturgy.[40]

Muhlenberg was sent by the Lutheran bishops in Germany, and he always insisted on strict conformity to Lutheran dogma. Muhlenberg's view of church unity was in direct opposition to Nicolaus Ludwig Zinzendorf's Moravian approach, with its goal of uniting various Pennsylvania German religious groups under a less rigid "Congregation of God in the Spirit". The differences between the two approaches led to permanent impasse between Lutherans and Moravians, especially after a December 1742 meeting in Philadelphia.[41] The Moravians settled Bethlehem and nearby areas and established schools for Native Americans.[37]

Judaism

In Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Dutch Christians and Pennsylvania German Jews have often maintained a special relationship due to their common German language and cultural heritage. Because both Yiddish and Pennsylvania Dutch are High German languages, there are strong similarities between the two languages and a limited degree of mutual intelligibility.[42] Historically, Pennsylvania Dutch Christians and Pennsylvania German Jews often had overlapping bonds in German-American business and community life. Due to this historical bond there are several mixed-faith cemeteries in Lehigh County, including Allentown's Fairview Cemetery, where German-Americans of both the Jewish and Protestant faiths are buried.[43] The cooking of Pennsylvania German Christians and Pennsylvania German Jews often overlaps, particularly vegetarian dishes that do not contain non-kosher ingredients such as pork or that mix meat and dairy together.[44] In 1987, the First United Church of Christ in Easton, Pennsylvania, hosted the annual meeting of the Pennsylvania German Society, the theme of which was the special bond between Pennsylvania German Christians and Pennsylvania German Jews. German Jews and German Christians held "quite ecumenical philosophies" about interfaith marriage and there are recorded instances of marriages between Jews and Christians within the German community. German Jews arriving in Pennsylvania often integrated into Pennsylvania Dutch communities because of their lack of knowledge of the English language. German Jews often lacked a trade and thus became peddlers, selling their wares within Pennsylvania Dutch society.[43]

A number of Pennsylvanian German Jews migrated to the Shenandoah Valley, travelling along the same route of migration as other Pennsylvania Dutch people.[45]

Pennsylvania Dutch today

Pennsylvania Dutch culture is still prevalent in some parts of Pennsylvania today. The Pennsylvania Dutch today speak English, though some still speak the Pennsylvania Dutch language among themselves. They share cultural similarities with the Mennonites in the same area. Pennsylvania Dutch English retains some German grammar and literally translated vocabulary, some phrases include "outen or out'n the lights" (German: "die Lichter loeschen") meaning "turn off the lights", "it's gonna make wet" (German: "es wird nass") meaning "its going to rain", and "its all" (German: "es ist alle") meaning "its all gone". They also sometimes leave out the verb in phrases turning "the trash needs to go out" in to "the trash needs out" (German: "der Abfall muss raus"), in alignment with German grammar. The Pennsylvania Dutch have some foods that are uncommon outside of places where they live. Some of these include shoo-fly pie, funnel cake, pepper cabbage, filling and jello salads such as strawberry pretzel salad.

Notable people

- Jacob Albright (1759–1808), founder of the Evangelical Association

- Anne F. Beiler (1949–present), founder of Auntie Anne's Pretzels

- John Birmelin (1873–1950), poet, playwright

- Solomon DeLong (1849–1925), writer, journalist

- George Ege (1748–1829), Representative for Pennsylvania

- Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969), 34th President of the United States

- H. L. Fischer (1822–1909), writer, translator

- Heinrich Funck (c. 1697–1730), miller, author, Mennonite bishop

- John Fries (1750–1818), auctioneer, organizer of Fries's Rebellion

- Betty Groff (1935–2015), celebrity chef, cookbook author

- Michael Hillegas (1729–1804), first Treasurer of the United States

- Hedda Hopper (1885–1966), actress, gossip columnist

- Ralph Kiner (1922–2014), Hall of Fame baseball player and Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Mets legend.

- William Kohl (1820–1892), sea captain, shipowner, shipbuilder, businessman

- Stephen Miller (1816–1881), 4th Governor of Minnesota

- Bodo Otto (1711–1787), physician in the Continental Army

- Harry Hess Reichard (1878–1956), writer, scholar

- Joseph Ritner (1780–1869), 8th Governor of Pennsylvania

- Victor Schertzinger (1888–1941), composer, film director, producer, screenwriter

- Dwight Schrute, fictional character in The Office, paper salesman.[46]

- Evelyn Ay Sempier (1933–2008), Miss America 1954

- Francis R. Shunk (1788–1848), 10th Governor of Pennsylvania

- Simon Snyder (1759–1813), 3rd Governor of Pennsylvania

- Clement Studebaker (1831–1901), co-founder of Studebaker Corporation

- Clement Studebaker Jr. (1871–1932), businessman, son of Clement Studebaker Sr.

- John Studebaker (1833–1917), co-founder of Studebaker Corporation

- Conrad Weiser (1696–1760), colonial diplomat between Pennsylvania and Native American nations.

See also

- Preston Barba, historian and linguist

- Helen Reimensnyder Martin, author

- Anna Balmer Myers, author

- Michael Werner (publisher)

- John Schmid, singer

- Fraktur (Pennsylvania German folk art)

- Hex sign

- Hiwwe wie Driwwe newspaper

- Kurrent handwriting

- Pennsylvania Dutch Country

- Pennsylvania Dutch cuisine

- Pennsylvania German language

- Schwenkfeldian (church)

- Old German Baptist Brethren (church)

- Pow-wow

- Dwight Schrute, fictional character on The Office

- Leanne Taylor, fictional character on Orange Is the New Black

References

- ^ Donald F. Durnbaugh. "Pennsylvania's Crazy Quilt of German Religious Groups". Journals.psu.edu. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Hughes Oliphant Old: The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, Volume 6: The Modern Age. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007, p. 606.

- ^ Mark L. Louden: Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. JHU Press, 2006, p.2

- ^ Hostetler, John A. (1993), Amish Society, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, p. 241

- ^ Irwin Richman: The Pennsylvania Dutch Country. Arcadia Publishing, 2004, p.16.

- ^ W. Haubrichs, "Theodiscus, Deutsch und Germanisch – drei Ethnonyme, drei Forschungsbegriffe. Zur Frage der Instrumentalisierung und Wertbesetzung deutscher Sprach- und Volksbezeichnungen." In: H. Beck et al., Zur Geschichte der Gleichung "germanisch-deutsch" (2004), 199–228

- ^ Mark L. Louden: Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. JHU Press, 2006, p.3-4

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ Lancaster, Discover. "PA Amish Lifestyle – How the community of Amish in PA live today". Discover Lancaster.

- ^ Steven M. Nolt (March 2008). Foreigners in their own land: Pennsylvania Germans in the early republic. p. 13. ISBN 9780271034447. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "Chapter Two – The History Of The German Immigration To America – The Brobst Chronicles". Homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Newman, George F., Newman, Dieter E. (2003). The Aebi-Eby Families of Switzerland, Germany, Austria, and North America, 1550–1850. Pennsylvania: NMN Enterprises.

- ^ Roeber 1988

- ^ a b "First German-Americans". Germanheritage.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2006.

- ^ "Historic Germantown – Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia". Philadelphiaencyclopedia.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "Germantown Mennonite Settlement (Pennsylvania, USA) – GAMEO". gameo.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Farley Grubb, "German Immigration to Pennsylvania, 1709 to 1820", Journal of Interdisciplinary History Vol. 20, No. 3 (Winter, 1990), pp. 417–436 in JSTOR

- ^ a b "German Settlement in Pennsylvania : An Overview" (PDF). Hsp.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "The Palatinate". Swissmennonite.org. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Pennsylvania Dutch Cooking: Traditional Dutch Dishes. Gettysburg, PA: Dutchcraft Company.

- ^ John B. Stoudt "The German Press in Pennsylvania and the American Revolution". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 59 (1938): 74–90 online

- ^ A. G.. Roeber, "Henry Miller's Staatsbote: A Revolutionary Journalist's Use of the Swiss Past", Yearbook of German-American Studies, 1990, Vol. 25, pp 57–76

- ^ Bowser, Les (2016). The Settlers of Monckton Township, Omemee ON: 250th Publications.

- ^ "Biography – SIMCOE, JOHN GRAVES – Volume V (1801–1820) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Biographi.ca. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "Ontario's Mennonite Heritage". Wampumkeeper.com. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Kitchener-Waterloo Ontario History – To Confederation". Kitchener.foundlocally.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "The Walter Bean Grand River Trail – Waterloo County: The Beginning". www.walterbeantrail.ca. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ a b "History of Markham, Ontario, Canada". Guidingstar.ca. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Ruprecht, Tony (December 14, 2010). Toronto's Many Faces. Dundurn. ISBN 9781459718043. Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "History" (PDF). Waterloo Historical Society 1930 Annual Meeting. Waterloo Historical Society. 1930. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ Elizabeth Bloomfield. "BUILDING COMMUNITY ON THE FRONTIER : the Mennonite contribution to shaping the Waterloo settlement to 1861" (PDF). Mhso.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "York County (Ontario, Canada)". Gameo.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "What is Pennsylvania Dutch?". Padutch.net. May 24, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "The Germans Come to North America". Anabaptists.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Shea, John G. (December 27, 2012). Making Authentic Pennsylvania Dutch Furniture: With Measured Drawings. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486157627 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gibbons, Phebe Earle (August 28, 1882). "Pennsylvania Dutch": And Other Essays. J.B. Lippincott & Company. p. 171. Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

Seventh Day Baptists pennsylvania dutch.

- ^ a b Murtagh, William J. (August 28, 1967). Moravian Architecture and Town Planning: Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and Other Eighteenth-Century American Settlements. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812216377. Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Donald F. Durnbaugh. "Pennsylvania's Crazy Quilt of German Religious Groups" (PDF). Journals.psu.edu. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Murtagh, William J. (August 28, 1967). Moravian Architecture and Town Planning: Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and Other Eighteenth-Century American Settlements. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812216377. Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Leonard R. Riforgiato, Missionary of moderation: Henry Melchior Muhlenberg and the Lutheran Church in America (1980)

- ^ Samuel R. Zeiser, "Moravians and Lutherans: Getting beyond the Zinzendorf-Muhlenberg Impasse", Transactions of the Moravian Historical Society, 1994, Vol. 28, pp. 15–29

- ^ "Yiddish and Pennsylvania Dutch". Yiddish Book Center. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "GERMAN JEWS' TIES WITH PA. DUTCH EXPLORED IN TALK". The Morning Call. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ "Saffron in the Pennsylvania Dutch Tradition". Fine Gardening. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ "Virtual Jewish World: Virginia, United States". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "Yes, Belsnickel is a Real Thing, and No, it's Not Just from 'The Office'". Arts + Culture. December 29, 2018.

Bibliography

- Bronner, Simon J. and Joshua R. Brown, eds. Pennsylvania Germans: An Interpretive Encyclopedia (: Johns Hopkins UP, 2017), xviii, 554 pp.

- Grubb, Farley. "German Immigration to Pennsylvania, 1709 to 1820", Journal of Interdisciplinary History Vol. 20, No. 3 (Winter, 1990), pp. 417–436 in JSTOR

- Louden, Mark L. Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

- McMurry, Sally, and Nancy Van Dolsen, eds. Architecture and Landscape of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1720–1920 (University of Pennsylvania Press; 2011) 250 studies their houses, churches, barns, outbuildings, commercial buildings, and landscapes

- Nolt, Steven, Foreigners in Their Own Land: Pennsylvania Germans in the Early American Republic, Penn State U. Press, 2002 ISBN 0-271-02199-3

- Pochmann, Henry A. German Culture in America: Philosophical and Literary Influences 1600–1900 (1957). 890pp; comprehensive review of German influence on Americans esp 19th century. online

- Pochmann, Henry A. and Arthur R. Schult. Bibliography of German Culture in America to 1940 (2nd ed 1982); massive listing, but no annotations.

- Roeber, A. G. Palatines, Liberty, and Property: German Lutherans in Colonial British America (1998)

- Roeber, A. G. "In German Ways? Problems and Potentials of Eighteenth-Century German Social and Emigration History", William & Mary Quarterly, Oct 1987, Vol. 44 Issue 4, pp 750–774 in JSTOR

External links

Media related to German diaspora in Pennsylvania at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to German diaspora in Pennsylvania at Wikimedia Commons- The Pennsylvania German Society

- Hiwwe wie Driwwe – the Pennsylvania German Newspaper

- Lancaster County tourism website

- Overview of Pennsylvania German Culture

- German-American Heritage Foundation of the USA in Washington, DC

- "Why the Pennsylvania German still prevails in the eastern section of the State", by George Mays, M.D.. Reading, Pa., Printed by Daniel Miller, 1904

- The Schwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center

- FamilyHart Pennsylvania Dutch Genealogy Family Pages and Database

- Alsatian Roots of Pennsylvania Dutch Firestones

- Pennsylvania Dutch Family History, Genealogy, Culture, and Life

- Several digitized books on Pennsylvania Dutch arts and crafts, design, and prints from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- In Pennsylvania German

- German-American culture in Pennsylvania

- German American

- German-Canadian culture in Ontario

- Amish in Pennsylvania

- Culture of Lancaster, Pennsylvania

- Culture of Ontario

- European-American society

- German diaspora in North America

- German-Jewish culture in Pennsylvania

- Indiana culture

- Maryland culture

- Mennonitism in Pennsylvania

- North Carolina culture

- Ohio culture

- Pennsylvania German culture

- Virginia culture

- West Virginia culture