Fermi paradox

The Fermi paradox is the conflict between the lack of clear, obvious evidence of extraterrestrial life and various high estimates for their existence.[1][2] As a 2015 article put it, "If life is so easy, someone from somewhere must have come calling by now."[3]

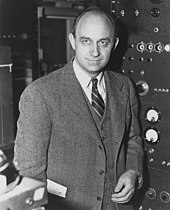

Italian-American physicist Enrico Fermi's name is associated with the paradox because of a casual conversation in the summer of 1950 with fellow physicists Edward Teller, Herbert York, and Emil Konopinski. While walking to lunch, the men discussed recent UFO reports and the possibility of faster-than-light travel. The conversation moved on to other topics, until during lunch Fermi blurted out, "But where is everybody?" (although the exact quote is uncertain).[3][4]

There have been many attempts to explain the Fermi paradox,[5][6] primarily suggesting that intelligent extraterrestrial beings are extremely rare, that the lifetime of such civilizations is short, or that they exist but (for various reasons) humans see no evidence. This suggests that at universe time and space scales, two intelligent civilizations would be unlikely ever to meet, even if many developed during the life of the universe.

Chain of reasoning

The following are some of the facts and hypotheses that together serve to highlight the apparent contradiction:

- There are billions of stars in the Milky Way similar to the Sun.[7][8]

- With high probability, some of these stars have Earth-like planets in a circumstellar habitable zone.[9]

- Many of these stars, and hence their planets, are much older than the Sun.[10][11] If the Earth is typical, some may have developed intelligent life long ago.

- Some of these civilizations may have developed interstellar travel, a step humans are investigating now.

- Even at the slow pace of currently envisioned interstellar travel, the Milky Way galaxy could be completely traversed in a few million years.[12]

- Since many of the stars similar to the Sun are billions of years older, Earth should have already been visited by extraterrestrial civilizations, or at least their probes.[13]

- However, there is no convincing evidence that this has happened.[12]

History

Fermi was not the first to ask the question. An earlier implicit mention was by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in an unpublished manuscript from 1933.[14] He noted "people deny the presence of intelligent beings on the planets of the universe" because "(i) if such beings exist they would have visited Earth, and (ii) if such civilizations existed then they would have given us some sign of their existence." This was not a paradox for others, who took this to imply the absence of extraterrestrial life. But it was one for him, since he believed in extraterrestrial life and the possibility of space travel. Therefore, he proposed what is now known as the zoo hypothesis and speculated that mankind is not yet ready for higher beings to contact us.[15] That Tsiolkovsky himself may not have been the first to discover the paradox is suggested by his above-mentioned reference to other people's reasons for denying the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations.

In 1975, Michael H. Hart published a detailed examination of the paradox, one of the first to do so.[12][16]: 27–28 [17]: 6 He argued that if intelligent extraterrestrials exist, and are capable of space travel, then the galaxy could have been colonized in a time much less than that of the age of the Earth. However, there is no observable evidence they have been here, which Hart called "Fact A".[17]: 6

Other names closely related to Fermi's question ("Where are they?") include the Great Silence,[18][19][20][21] and silentium universi[21] (Latin for "silence of the universe"), though these only refer to one portion of the Fermi Paradox, that humans see no evidence of other civilizations.

Original conversations

Los Alamos, New Mexico, United States

In the summer of 1950 at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, Enrico Fermi and co-workers Emil Konopinski, Edward Teller, and Herbert York had one or several lunchtime conversations.[4][22]

As three of the men walked to lunch, Teller writes that he has a "vague recollection" to the effect that "we talked about flying saucers and the obvious statement that the flying saucers are not real." Konopinski joined the others while the conversation was in progress. He remembered a magazine cartoon which showed aliens stealing New York City trash cans and added this humorous aspect to the conversation.[23] He writes, "More amusing was Fermi's comment, that it was a very reasonable theory since it accounted for two separate phenomena: the reports of flying saucers as well as the disappearance of the trash cans." And yet, when Eric Jones wrote to the surviving men decades later, only Konopinski remembered that the cartoon had been part of the conversation.[4]

Teller writes that he thinks Fermi directed the question to him: "How probable is it that within the next ten years we shall have clear evidence of a material object moving faster than light?" Teller answered one in a million. Fermi said, "This is much too low. The probability is more like ten percent." Teller also writes that ten percent was "the well known figure for a Fermi miracle."[4]

Herb York does not remember a previous conversation, although he says it makes sense given how all three later reacted to Fermi's outburst.[note 1]

After sitting down for lunch, and when the conversation had already moved on to other topics, Fermi suddenly blurted out, "Where is everybody?" (Teller's letter), or "Don't you ever wonder where everybody is?" (York's letter), or "But where is everybody?" (Konopinski's letter).[4]

Teller wrote, "The result of his question was general laughter because of the strange fact that in spite of Fermi's question coming from the clear blue, everybody around the table seemed to understand at once that he was talking about extraterrestrial life."[4]

Herbert York wrote, "Somehow (and perhaps it was connected to the prior conversation in the way you describe, even though I do not remember that) we all knew he meant extra-terrestrials."[4]

Emil Konopinski merely wrote, "It was his way of putting it that drew laughs from us."[4]

Regarding the continuation of the conversation, York wrote in 1984 that Fermi "followed up with a series of calculations on the probability of earthlike planets, the probability of life given an earth, the probability of humans given life, the likely rise and duration of high technology, and so on. He concluded on the basis of such calculations that we ought to have been visited long ago and many times over."[4]

Teller remembers that not much came of this conversation "except perhaps a statement that the distances to the next location of living beings may be very great and that, indeed, as far as our galaxy is concerned, we are living somewhere in the sticks, far removed from the metropolitan area of the galactic center."[4]

Teller wrote "maybe approximately eight of us sat down together for lunch."[4][note 2] Both York and Konopinski remember that it was just the four of them.[note 3][note 4]

Fermi died of cancer in 1954. However, in letters to the three surviving men decades later in 1984, Dr. Eric Jones of Los Alamos was able to partially put the original conversation back together. He informed each of the men that he wished to include a reasonably accurate version or composite in the written proceedings he was putting together for a previously-held conference entitled "Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience".[4][24]

Jones first sent a letter to Edward Teller which included a secondhand account from Hans Mark. Teller responded, and then Jones sent Teller's letter to Herbert York. York responded, and finally, Jones sent both Teller's and York's letters to Emil Konopinski who also responded. Furthermore, Konopinski was able to later identify a cartoon which Jones found as the one involved in the conversation and thereby help to settle the time period as being the summer of 1950.[4]

Basis

The Fermi paradox is a conflict between the argument that scale and probability seem to favor intelligent life being common in the universe, and the total lack of evidence of intelligent life having ever arisen anywhere other than on Earth.

The first aspect of the Fermi paradox is a function of the scale or the large numbers involved: there are an estimated 200–400 billion stars in the Milky Way[25] (2–4 × 1011) and 70 sextillion (7×1022) in the observable universe.[26] Even if intelligent life occurs on only a minuscule percentage of planets around these stars, there might still be a great number of extant civilizations, and if the percentage were high enough it would produce a significant number of extant civilizations in the Milky Way. This assumes the mediocrity principle, by which Earth is a typical planet.

The second aspect of the Fermi paradox is the argument of probability: given intelligent life's ability to overcome scarcity, and its tendency to colonize new habitats, it seems possible that at least some civilizations would be technologically advanced, seek out new resources in space, and colonize their own star system and, subsequently, surrounding star systems. Since there is no significant evidence on Earth, or elsewhere in the known universe, of other intelligent life after 13.8 billion years of the universe's history, there is a conflict requiring a resolution. Some examples of possible resolutions are that intelligent life is rarer than is thought, that assumptions about the general development or behavior of intelligent species are flawed, or, more radically, that current scientific understanding of the nature of the universe itself is quite incomplete.

The Fermi paradox can be asked in two ways.[note 5] The first is, "Why are no aliens or their artifacts found here on Earth, or in the Solar System?". If interstellar travel is possible, even the "slow" kind nearly within the reach of Earth technology, then it would only take from 5 million to 50 million years to colonize the galaxy.[27] This is relatively brief on a geological scale, let alone a cosmological one. Since there are many stars older than the Sun, and since intelligent life might have evolved earlier elsewhere, the question then becomes why the galaxy has not been colonized already. Even if colonization is impractical or undesirable to all alien civilizations, large-scale exploration of the galaxy could be possible by probes. These might leave detectable artifacts in the Solar System, such as old probes or evidence of mining activity, but none of these have been observed.

The second form of the question is "Why do we see no signs of intelligence elsewhere in the universe?". This version does not assume interstellar travel, but includes other galaxies as well. For distant galaxies, travel times may well explain the lack of alien visits to Earth, but a sufficiently advanced civilization could potentially be observable over a significant fraction of the size of the observable universe.[28] Even if such civilizations are rare, the scale argument indicates they should exist somewhere at some point during the history of the universe, and since they could be detected from far away over a considerable period of time, many more potential sites for their origin are within range of human observation. It is unknown whether the paradox is stronger for the Milky Way galaxy or for the universe as a whole.[29]

Drake equation

The theories and principles in the Drake equation are closely related to the Fermi paradox.[30] The equation was formulated by Frank Drake in 1961 in an attempt to find a systematic means to evaluate the numerous probabilities involved in the existence of alien life. The equation is presented as follows:

Where — the number of technologically advanced civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy — is asserted to be the product of

- , the rate of formation of stars in the galaxy;

- , the fraction of those stars with planetary systems;

- , the number of planets, per solar system, with an environment suitable for organic life;

- , the fraction of those suitable planets whereon organic life actually appears;

- , the fraction of habitable planets whereon intelligent life actually appears;

- , the fraction of civilizations that reach the technological level whereby detectable signals may be dispatched; and

- , the length of time that those civilizations dispatch their signals.

The fundamental problem is that the last four terms (, , , and ) are completely unknown, rendering statistical estimates impossible.[31]

The Drake equation has been used by both optimists and pessimists, with wildly differing results. The first scientific meeting on the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI), which had 10 attendees including Frank Drake and Carl Sagan, speculated that the number of civilizations was roughly between 1,000 and 100,000,000 civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy.[32] Conversely, Frank Tipler and John D. Barrow used pessimistic numbers and speculated that the average number of civilizations in a galaxy is much less than one.[33] Almost all arguments involving the Drake equation suffer from the overconfidence effect, a common error of probabilistic reasoning about low-probability events, by guessing specific numbers for likelihoods of events whose mechanism is not yet understood, such as the likelihood of abiogenesis on an Earth-like planet, with current likelihood estimates varying over many hundreds of orders of magnitude. An analysis that takes into account some of the uncertainty associated with this lack of understanding has been carried out by Anders Sandberg, Eric Drexler and Toby Ord,[34] and suggests "a substantial ex ante probability of there being no other intelligent life in our observable universe".

Great Filter

The Great Filter, a concept introduced by Robin Hanson in 1996, represents whatever natural phenomena that would make it unlikely for life to evolve from inanimate matter to an advanced civilization.[35][3] The most commonly agreed-upon low probability event is abiogenesis: a gradual process of increasing complexity of the first self-replicating molecules by a randomly occurring chemical process. Other proposed great filters are the emergence of eukaryotic cells[note 6] or of meiosis or some of the steps involved in the evolution of a brain capable of complex logical deductions.[36]

Astrobiologists Dirk Schulze-Makuch and William Bains, reviewing the history of life on Earth, including convergent evolution, concluded that transitions such as oxygenic photosynthesis, the eukaryotic cell, multicellularity, and tool-using intelligence are likely to occur on any Earth-like planet given enough time. They argue that the Great Filter may be abiogenesis, the rise of technological human-level intelligence, or an inability to settle other worlds because of self-destruction or a lack of resources.[37]

Empirical evidence

There are two parts of the Fermi paradox that rely on empirical evidence—that there are many potential habitable planets, and that humans see no evidence of life. The first point, that many suitable planets exist, was an assumption in Fermi's time but is now supported by the discovery that exoplanets are common. Current models predict billions of habitable worlds in the Milky Way.[38]

The second part of the paradox, that humans see no evidence of extraterrestrial life, is also an active field of scientific research. This includes both efforts to find any indication of life,[39] and efforts specifically directed to finding intelligent life. These searches have been made since 1960, and several are ongoing.[note 7]

Although astronomers do not usually search for extraterrestrials, they have observed phenomena that they could not immediately explain without positing an intelligent civilization as the source. For example, pulsars, when first discovered in 1967, were called little green men (LGM) because of the precise repetition of their pulses.[40] In all cases, explanations with no need for intelligent life have been found for such observations,[note 8] but the possibility of discovery remains.[41] Proposed examples include asteroid mining that would change the appearance of debris disks around stars,[42] or spectral lines from nuclear waste disposal in stars.[43]

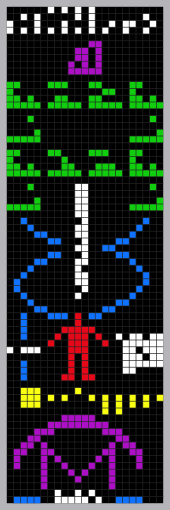

Electromagnetic emissions

Radio technology and the ability to construct a radio telescope are presumed to be a natural advance for technological species,[44] theoretically creating effects that might be detected over interstellar distances. The careful searching for non-natural radio emissions from space may lead to the detection of alien civilizations. Sensitive alien observers of the Solar System, for example, would note unusually intense radio waves for a G2 star due to Earth's television and telecommunication broadcasts. In the absence of an apparent natural cause, alien observers might infer the existence of a terrestrial civilization. Such signals could be either "accidental" by-products of a civilization, or deliberate attempts to communicate, such as the Arecibo message. It is unclear whether "leakage", as opposed to a deliberate beacon, could be detected by an extraterrestrial civilization. The most sensitive radio telescopes on Earth, as of 2019[update], would not be able to detect non-directional radio signals even at a fraction of a light-year away,[45] but other civilizations could hypothetically have much better equipment.[46]

A number of astronomers and observatories have attempted and are attempting to detect such evidence, mostly through the SETI organization. Several decades of SETI analysis have not revealed any unusually bright or meaningfully repetitive radio emissions.[47]

Direct planetary observation

Exoplanet detection and classification is a very active sub-discipline in astronomy, and the first possibly terrestrial planet discovered within a star's habitable zone was found in 2007.[48] New refinements in exoplanet detection methods, and use of existing methods from space (such as the Kepler and TESS missions) are starting to detect and characterize Earth-size planets, and determine if they are within the habitable zones of their stars. Such observational refinements may allow to better gauge how common potentially habitable worlds are.[49]

Conjectures about interstellar probes

The Hart-Tipler conjecture is a form of contraposition which states that because no interstellar probes have been detected, there likely is no other intelligent life in the universe, as such life should be expected to eventually create and launch such probes.[50][51] Self-replicating probes could exhaustively explore a galaxy the size of the Milky Way in as little as a million years.[12] If even a single civilization in the Milky Way attempted this, such probes could spread throughout the entire galaxy. Another speculation for contact with an alien probe—one that would be trying to find human beings—is an alien Bracewell probe. Such a hypothetical device would be an autonomous space probe whose purpose is to seek out and communicate with alien civilizations (as opposed to von Neumann probes, which are usually described as purely exploratory). These were proposed as an alternative to carrying a slow speed-of-light dialogue between vastly distant neighbors. Rather than contending with the long delays a radio dialogue would suffer, a probe housing an artificial intelligence would seek out an alien civilization to carry on a close-range communication with the discovered civilization. The findings of such a probe would still have to be transmitted to the home civilization at light speed, but an information-gathering dialogue could be conducted in real time.[52]

Direct exploration of the Solar System has yielded no evidence indicating a visit by aliens or their probes. Detailed exploration of areas of the Solar System where resources would be plentiful may yet produce evidence of alien exploration,[53][54] though the entirety of the Solar System is vast and difficult to investigate. Attempts to signal, attract, or activate hypothetical Bracewell probes in Earth's vicinity have not succeeded.[55]

Searches for stellar-scale artifacts

In 1959, Freeman Dyson observed that every developing human civilization constantly increases its energy consumption, and, he conjectured, a civilization might try to harness a large part of the energy produced by a star. He proposed that a Dyson sphere could be a possible means: a shell or cloud of objects enclosing a star to absorb and utilize as much radiant energy as possible. Such a feat of astroengineering would drastically alter the observed spectrum of the star involved, changing it at least partly from the normal emission lines of a natural stellar atmosphere to those of black-body radiation, probably with a peak in the infrared. Dyson speculated that advanced alien civilizations might be detected by examining the spectra of stars and searching for such an altered spectrum.[56][57][58]

There have been some attempts to find evidence of the existence of Dyson spheres that would alter the spectra of their core stars.[59] Direct observation of thousands of galaxies has shown no explicit evidence of artificial construction or modifications.[57][58][60][61] In October 2015, there was some speculation that a dimming of light from star KIC 8462852, observed by the Kepler Space Telescope, could have been a result of Dyson sphere construction.[62][63] However, in 2018, observations determined that the amount of dimming varied by the frequency of the light, pointing to dust, rather than an opaque object such as a Dyson sphere, as the culprit for causing the dimming.[64][65]

Hypothetical explanations for the paradox

Rarity of intelligent life

Extraterrestrial life is rare or non-existent

Those who think that intelligent extraterrestrial life is (nearly) impossible argue that the conditions needed for the evolution of life—or at least the evolution of biological complexity—are rare or even unique to Earth. Under this assumption, called the rare Earth hypothesis, a rejection of the mediocrity principle, complex multicellular life is regarded as exceedingly unusual.[66]

The rare Earth hypothesis argues that the evolution of biological complexity requires a host of fortuitous circumstances, such as a galactic habitable zone, a star and planet(s) having the requisite conditions, such as enough of a continuous habitable zone, the advantage of a giant guardian like Jupiter and a large moon, conditions needed to ensure the planet has a magnetosphere and plate tectonics, the chemistry of the lithosphere, atmosphere, and oceans, the role of "evolutionary pumps" such as massive glaciation and rare bolide impacts. And perhaps most importantly, advanced life needs whatever it was that led to the transition of (some) prokaryotic cells to eukaryotic cells, sexual reproduction and the Cambrian explosion.

In his book Wonderful Life (1989), Stephen Jay Gould suggested that if the "tape of life" were rewound to the time of the Cambrian explosion, and one or two tweaks made, human beings most probably never would have evolved. Other thinkers such as Fontana, Buss, and Kauffman have written about the self-organizing properties of life.[67]

Extraterrestrial intelligence is rare or non-existent

It is possible that even if complex life is common, intelligence (and consequently civilizations) is not.[36] While there are remote sensing techniques that could perhaps detect life-bearing planets without relying on the signs of technology,[68][69] none of them have any ability to tell if any detected life is intelligent. This is sometimes referred to as the "algae vs. alumnae" problem.[70]

Charles Lineweaver states that when considering any extreme trait in an animal, intermediate stages do not necessarily produce "inevitable" outcomes. For example, large brains are no more "inevitable", or convergent, than are the long noses of animals such as aardvarks and elephants. Humans, apes, whales, dolphins, octopuses, and squids are among the small group of definite or probable intelligence on Earth. And as he points out, "dolphins have had ~20 million years to build a radio telescope and have not done so".[36]

In addition, Rebecca Boyle points out that of all the species who have ever evolved in the history of life on the planet Earth, only one—we human beings and only in the beginning stages—has ever become space-faring.[71]

Periodic extinction by natural events

New life might commonly die out due to runaway heating or cooling on their fledgling planets.[72] On Earth, there have been numerous major extinction events that destroyed the majority of complex species alive at the time; the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs is the best known example. These are thought to have been caused by events such as impact from a large meteorite, massive volcanic eruptions, or astronomical events such as gamma-ray bursts.[73] It may be the case that such extinction events are common throughout the universe and periodically destroy intelligent life, or at least its civilizations, before the species is able to develop the technology to communicate with other intelligent species.[74]

Evolutionary explanations

Intelligent alien species have not developed advanced technologies

It may be that while alien species with intelligence exist, they are primitive or have not reached the level of technological advancement necessary to communicate. Along with non-intelligent life, such civilizations would also be very difficult to detect.[70] A trip using conventional rockets would take hundreds of thousands of years to reach the nearest stars.[75]

To skeptics, the fact that in the history of life on the Earth only one species has developed a civilization to the point of being capable of spaceflight and radio technology lends more credence to the idea that technologically advanced civilizations are rare in the universe.[76]

Another hypothesis in this category is the "Water World hypothesis". According to author and scientist David Brin: "it turns out that our Earth skates the very inner edge of our sun’s continuously habitable—or 'Goldilocks'—zone. And Earth may be anomalous. It may be that because we are so close to our sun, we have an anomalously oxygen-rich atmosphere, and we have anomalously little ocean for a water world. In other words, 32 percent continental mass may be high among water worlds..."[77] Brin continues, "In which case, the evolution of creatures like us, with hands and fire and all that sort of thing, may be rare in the galaxy. In which case, when we do build starships and head out there, perhaps we’ll find lots and lots of life worlds, but they’re all like Polynesia. We’ll find lots and lots of intelligent lifeforms out there, but they’re all dolphins, whales, squids, who could never build their own starships. What a perfect universe for us to be in, because nobody would be able to boss us around, and we’d get to be the voyagers, the Star Trek people, the starship builders, the policemen, and so on."[77]

It is the nature of intelligent life to destroy itself

This is the argument that technological civilizations may usually or invariably destroy themselves before or shortly after developing radio or spaceflight technology. The astrophysicist Sebastian von Hoerner stated that the progress of science and technology on Earth was driven by two factors—the struggle for domination and the desire for an easy life. The former potentially leads to complete destruction, while the latter may lead to biological or mental degeneration.[78] Possible means of annihilation via major global issues, where global interconnectedness actually makes humanity more vulnerable than resilient,[79] are many,[80] including war, accidental environmental contamination or damage, the development of biotechnology,[81] synthetic life like mirror life,[82] resource depletion, climate change,[83] or poorly-designed artificial intelligence. This general theme is explored both in fiction and in scientific hypothesizing.[84]

In 1966, Sagan and Shklovskii speculated that technological civilizations will either tend to destroy themselves within a century of developing interstellar communicative capability or master their self-destructive tendencies and survive for billion-year timescales.[85] Self-annihilation may also be viewed in terms of thermodynamics: insofar as life is an ordered system that can sustain itself against the tendency to disorder, Stephen Hawking's "external transmission" or interstellar communicative phase, where knowledge production and knowledge management is more important than transmission of information via evolution, may be the point at which the system becomes unstable and self-destructs.[86][87] Here, Hawking emphasizes self-design of the human genome (transhumanism) or enhancement via machines (e.g., brain–computer interface) to enhance human intelligence and reduce aggression, without which he implies human civilization may be too stupid collectively to survive an increasingly unstable system. For instance, the development of technologies during the "external transmission" phase, such as weaponization of artificial general intelligence or antimatter, may not be met by concomitant increases in human ability to manage its own inventions. Consequently, disorder increases in the system: global governance may become increasingly destabilized, worsening humanity's ability to manage the possible means of annihilation listed above, resulting in global societal collapse.

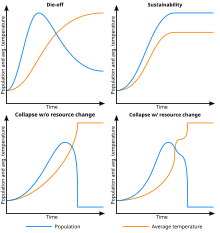

Using extinct civilizations such as Easter Island (Rapa Nui) as models, a study conducted in 2018 by Adam Frank et al. posited that climate change induced by "energy intensive" civilizations may prevent sustainability within such civilizations, thus explaining the paradoxical lack of evidence for intelligent extraterrestrial life. According to his model, possible outcomes of climate change include gradual population decline until an equilibrium is reached; a scenario where sustainability is attained and both population and surface temperature level off; and societal collapse, including scenarios where a tipping point is crossed.[88]

A less theoretical example might be the resource-depletion issue on Polynesian islands, of which Easter Island is only the best known. David Brin points out that during the expansion phase from 1500 BC to 800 AD there were cycles of overpopulation followed by what might be called periodic cullings of adult males through war or ritual. He writes, "There are many stories of islands whose men were almost wiped out—sometimes by internal strife, and sometimes by invading males from other islands."[89]

It is the nature of intelligent life to destroy others

Another hypothesis is that an intelligent species beyond a certain point of technological capability will destroy other intelligent species as they appear, perhaps by using self-replicating probes. Science fiction writer Fred Saberhagen has explored this idea in his Berserker series, as has physicist Gregory Benford[90] and, as well, science fiction writer Greg Bear in his The Forge of God novel,[91] and later Liu Cixin in his The Three-Body Problem series.

A species might undertake such extermination out of expansionist motives, greed, paranoia, or aggression. In 1981, cosmologist Edward Harrison argued that such behavior would be an act of prudence: an intelligent species that has overcome its own self-destructive tendencies might view any other species bent on galactic expansion as a threat.[92] It has also been suggested that a successful alien species would be a superpredator, as are humans.[93][94]: 112 Another possibility invokes the "tragedy of the commons" and the anthropic principle: the first lifeform to achieve interstellar travel will necessarily (even if unintentionally) prevent competitors from arising, and humans simply happen to be first.[95][96]

Civilizations only broadcast detectable signals for a brief period of time

It may be that alien civilizations are detectable through their radio emissions for only a short time, reducing the likelihood of spotting them. The usual assumption is that civilizations outgrow radio through technological advancement.[97] However, there could be other leakage such as that from microwaves used to transmit power from solar satellites to ground receivers.[98]

Regarding the first point, in a 2006 Sky & Telescope article, Seth Shostak wrote, "Moreover, radio leakage from a planet is only likely to get weaker as a civilization advances and its communications technology gets better. Earth itself is increasingly switching from broadcasts to leakage-free cables and fiber optics, and from primitive but obvious carrier-wave broadcasts to subtler, hard-to-recognize spread-spectrum transmissions."[99]

More hypothetically, advanced alien civilizations may evolve beyond broadcasting at all in the electromagnetic spectrum and communicate by technologies not developed or used by mankind.[100] Some scientists have hypothesized that advanced civilizations may send neutrino signals.[101] If such signals exist, they could be detectable by neutrino detectors that are now under construction for other goals.[102]

Alien life may be too alien

Another possibility is that human theoreticians have underestimated how much alien life might differ from that on Earth. Aliens may be psychologically unwilling to attempt to communicate with human beings. Perhaps human mathematics is parochial to Earth and not shared by other life,[103] though others argue this can only apply to abstract math since the math associated with physics must be similar (in results, if not in methods).[104]

Physiology might also cause a communication barrier. Carl Sagan speculated that an alien species might have a thought process orders of magnitude slower (or faster) than that of humans.[105] A message broadcast by that species might well seem like random background noise to humans, and therefore go undetected.

Another thought is that technological civilizations invariably experience a technological singularity and attain a post-biological character.[106] Hypothetical civilizations of this sort may have advanced drastically enough to render communication impossible.[107][108][109]

In his 2009 book, SETI scientist Seth Shostak wrote, "Our experiments [such as plans to use drilling rigs on Mars] are still looking for the type of extraterrestrial that would have appealed to Percival Lowell [astronomer who believed he had observed canals on Mars]."[110]

Paul Davies states that 500 years ago the very idea of a computer doing work merely by manipulating internal data may not have been viewed as a technology at all. He writes, "Might there be a still higher level ... If so, this 'third level' would never be manifest through observations made at the informational level, still less the matter level. There is no vocabulary to describe the third level, but that doesn't mean it is non-existent, and we need to be open to the possibility that alien technology may operate at the third level, or maybe the fourth, fifth ... levels."[111]

Sociological explanations

Colonization is not the cosmic norm

In response to Tipler's idea of self-replicating probes, Stephen Jay Gould wrote, "I must confess that I simply don’t know how to react to such arguments. I have enough trouble predicting the plans and reactions of the people closest to me. I am usually baffled by the thoughts and accomplishments of humans in different cultures. I’ll be damned if I can state with certainty what some extraterrestrial source of intelligence might do."[112][113]

Alien species may have only settled part of the galaxy

A February 2019 article in Popular Science states, "Sweeping across the Milky Way and establishing a unified galactic empire might be inevitable for a monolithic super-civilization, but most cultures are neither monolithic nor super—at least if our experience is any guide."[114] Astrophysicist Adam Frank, along with co-authors such as astronomer Jason Wright, ran a variety of simulations in which they varied such factors as settlement lifespans, fractions of suitable planets, and recharge times between launches. They found many of their simulations seemingly resulted in a "third category" in which the Milky Way remains partially settled indefinitely.[114] The abstract to their 2019 paper states, "These results break the link between Hart's famous 'Fact A' (no interstellar visitors on Earth now) and the conclusion that humans must, therefore, be the only technological civilization in the galaxy. Explicitly, our solutions admit situations where our current circumstances are consistent with an otherwise settled, steady-state galaxy."[115]

Alien species may not live on planets

Some colonization scenarios predict spherical expansion across star systems, with continued expansion coming from the systems just previously settled. It has been suggested that this would cause a strong selection process among the colonization front favoring cultural or biological adaptations to living in starships or space habitats. As a result, they may forgo living on planets.[116]

This may result in the destruction of terrestrial planets in these systems for use as building materials, thus preventing the development of life on those worlds. Or, they may have an ethic of protection for "nursery worlds", and protect them in a similar fashion to the zoo hypothesis.[116]

Alien species may isolate themselves from the outside world

It has been suggested that some advanced beings may divest themselves of physical form, create massive artificial virtual environments, transfer themselves into these environments through mind uploading, and exist totally within virtual worlds, ignoring the external physical universe.[117]

It may also be that intelligent alien life develops an "increasing disinterest" in their outside world.[94]: 86 Possibly any sufficiently advanced society will develop highly engaging media and entertainment well before the capacity for advanced space travel, with the rate of appeal of these social contrivances being destined, because of their inherent reduced complexity, to overtake any desire for complex, expensive endeavors such as space exploration and communication. Once any sufficiently advanced civilization becomes able to master its environment, and most of its physical needs are met through technology, various "social and entertainment technologies", including virtual reality, are postulated to become the primary drivers and motivations of that civilization.[118]

Economic explanations

Lack of resources needed to physically spread throughout the galaxy

The ability of an alien culture to colonize other star systems is based on the idea that interstellar travel is technologically feasible. While the current understanding of physics rules out the possibility of faster-than-light travel, it appears that there are no major theoretical barriers to the construction of "slow" interstellar ships, even though the engineering required is considerably beyond present capabilities. This idea underlies the concept of the Von Neumann probe and the Bracewell probe as a potential evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence.

It is possible, however, that present scientific knowledge cannot properly gauge the feasibility and costs of such interstellar colonization. Theoretical barriers may not yet be understood, and the resources needed may be so great as to make it unlikely that any civilization could afford to attempt it. Even if interstellar travel and colonization are possible, they may be difficult, leading to a colonization model based on percolation theory.[119][120]

Colonization efforts may not occur as an unstoppable rush, but rather as an uneven tendency to "percolate" outwards, within an eventual slowing and termination of the effort given the enormous costs involved and the expectation that colonies will inevitably develop a culture and civilization of their own. Colonization may thus occur in "clusters", with large areas remaining uncolonized at any one time.[119][120]

It is cheaper to transfer information than explore physically

If a human-capability machine construct, such as via mind uploading, is possible, and if it is possible to transfer such constructs over vast distances and rebuild them on a remote machine, then it might not make strong economic sense to travel the galaxy by spaceflight. After the first civilization has physically explored or colonized the galaxy, as well as sent such machines for easy exploration, then any subsequent civilizations, after having contacted the first, may find it cheaper, faster, and easier to explore the galaxy through intelligent mind transfers to the machines built by the first civilization, which is cheaper than spaceflight by a factor of 108–1017. However, since a star system needs only one such remote machine, and the communication is most likely highly directed, transmitted at high-frequencies, and at a minimal power to be economical, such signals would be hard to detect from Earth.[121]

Discovery of extraterrestrial life is too difficult

Humans have not listened properly

There are some assumptions that underlie the SETI programs that may cause searchers to miss signals that are present. Extraterrestrials might, for example, transmit signals that have a very high or low data rate, or employ unconventional (in human terms) frequencies, which would make them hard to distinguish from background noise. Signals might be sent from non-main sequence star systems that humans search with lower priority; current programs assume that most alien life will be orbiting Sun-like stars.[122]

The greatest challenge is the sheer size of the radio search needed to look for signals (effectively spanning the entire observable universe), the limited amount of resources committed to SETI, and the sensitivity of modern instruments. SETI estimates, for instance, that with a radio telescope as sensitive as the Arecibo Observatory, Earth's television and radio broadcasts would only be detectable at distances up to 0.3 light-years, less than 1/10 the distance to the nearest star. A signal is much easier to detect if it consists of a deliberate, powerful transmission directed at Earth. Such signals could be detected at ranges of hundreds to tens of thousands of light-years distance.[123] However, this means that detectors must be listening to an appropriate range of frequencies, and be in that region of space to which the beam is being sent. Many SETI searches assume that extraterrestrial civilizations will be broadcasting a deliberate signal, like the Arecibo message, in order to be found.

Thus, to detect alien civilizations through their radio emissions, Earth observers either need more sensitive instruments or must hope for fortunate circumstances: that the broadband radio emissions of alien radio technology are much stronger than humanity's own; that one of SETI's programs is listening to the correct frequencies from the right regions of space; or that aliens are deliberately sending focused transmissions in Earth's general direction.

Humans have not listened for long enough

Humanity's ability to detect intelligent extraterrestrial life has existed for only a very brief period—from 1937 onwards, if the invention of the radio telescope is taken as the dividing line—and Homo sapiens is a geologically recent species. The whole period of modern human existence to date is a very brief period on a cosmological scale, and radio transmissions have only been propagated since 1895. Thus, it remains possible that human beings have neither existed long enough nor made themselves sufficiently detectable to be found by extraterrestrial intelligence.[124]

Intelligent life may be too far away

It may be that non-colonizing technologically capable alien civilizations exist, but that they are simply too far apart for meaningful two-way communication.[94]: 62–71 Sebastian von Hoerner estimated the average duration of civilization at 6,500 years and the average distance between civilizations in the Milky Way at 1,000 light years.[78] If two civilizations are separated by several thousand light-years, it is possible that one or both cultures may become extinct before meaningful dialogue can be established. Human searches may be able to detect their existence, but communication will remain impossible because of distance. It has been suggested that this problem might be ameliorated somewhat if contact and communication is made through a Bracewell probe. In this case at least one partner in the exchange may obtain meaningful information. Alternatively, a civilization may simply broadcast its knowledge, and leave it to the receiver to make what they may of it. This is similar to the transmission of information from ancient civilizations to the present,[125] and humanity has undertaken similar activities like the Arecibo message, which could transfer information about Earth's intelligent species, even if it never yields a response or does not yield a response in time for humanity to receive it. It is possible that observational signatures of self-destroyed civilizations could be detected, depending on the destruction scenario and the timing of human observation relative to it.[126]

A related speculation by Sagan and Newman suggests that if other civilizations exist, and are transmitting and exploring, their signals and probes simply have not arrived yet.[127] However, critics have noted that this is unlikely, since it requires that humanity's advancement has occurred at a very special point in time, while the Milky Way is in transition from empty to full. This is a tiny fraction of the lifespan of a galaxy under ordinary assumptions, so the likelihood that humanity is in the midst of this transition is considered low in the paradox.[128]

Some SETI skeptics may also believe that humanity is at a very special point of time. Specifically, a transitional period from no space-faring societies to one space-faring society, namely that of human beings.[128]

Intelligent life may exist hidden from view

Planetary scientist Alan Stern put forward the idea that there could be a number of worlds with subsurface oceans (such as Jupiter's Europa or Saturn's Enceladus). The surface would provide a large degree of protection from such things as cometary impacts and nearby supernovae, as well as creating a situation in which a much broader range of orbits are acceptable. Life, and potentially intelligence and civilization, could evolve. Stern states, "If they have technology, and let's say they're broadcasting, or they have city lights or whatever—we can't see it in any part of the spectrum, except maybe very-low-frequency [radio]."[129][130]

Willingness to communicate

Everyone is listening but no one is transmitting

Alien civilizations might be technically capable of contacting Earth, but could be only listening instead of transmitting.[131] If all or most civilizations act in the same way, the galaxy could be full of civilizations eager for contact, but everyone is listening and no one is transmitting. This is the so-called SETI Paradox.[132]

The only civilization known, humanity, does not explicitly transmit, except for a few small efforts.[131] Even these efforts, and certainly any attempt to expand them, are controversial.[133] It is not even clear humanity would respond to a detected signal—the official policy within the SETI community[134] is that "[no] response to a signal or other evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence should be sent until appropriate international consultations have taken place". However, given the possible impact of any reply,[135] it may be very difficult to obtain any consensus on who would speak and what they would say.

Communication is dangerous

An alien civilization might feel it is too dangerous to communicate, either for humanity or for them. It is argued that when very different civilizations have met on Earth, the results have often been disastrous for one side or the other, and the same may well apply to interstellar contact.[136] Even contact at a safe distance could lead to infection by computer code[137] or even ideas themselves.[138] Perhaps prudent civilizations actively hide not only from Earth but from everyone, out of fear of other civilizations.[139]

Perhaps the Fermi paradox itself—or the alien equivalent of it—is the reason for any civilization to avoid contact with other civilizations, even if no other obstacles existed. From any one civilization's point of view, it would be unlikely for them to be the first ones to make first contact. Therefore, according to this reasoning, it is likely that previous civilizations faced fatal problems with first contact and doing so should be avoided. So perhaps every civilization keeps quiet because of the possibility that there is a real reason for others to do so.[18]

In Liu Cixin's 2008 novel The Dark Forest, the author proposes a literary explanation for the Fermi paradox in which many multiple alien civilizations exist, but are both silent and paranoid, destroying any nascent lifeforms loud enough to make themselves known.[140] This is because any other intelligent life may represent a future threat. As a result, Liu's universe contains a plethora of quiet civilizations which do not reveal themselves, as in a "dark forest"...filled with "armed hunter(s) stalking through the trees like a ghost".[141][142][143] This idea has come to be known as the dark forest hypothesis.[144][145][146]

Earth is deliberately avoided

The zoo hypothesis states that intelligent extraterrestrial life exists and does not contact life on Earth to allow for its natural evolution and development.[147] A variation on the zoo hypothesis is the laboratory hypothesis, where humanity has been or is being subject to experiments,[147][5] with Earth or the Solar System effectively serving as a laboratory. The zoo hypothesis may break down under the uniformity of motive flaw: all it takes is a single culture or civilization to decide to act contrary to the imperative within humanity's range of detection for it to be abrogated, and the probability of such a violation of hegemony increases with the number of civilizations,[27][148] tending not towards a 'Galactic Club' with a unified foreign policy with regard to life on Earth but multiple 'Galactic Cliques'.[149] However, if artificial superintelligences dominate galactic life, and if it is true that such intelligences tend towards merged hegemonic behavior, then this would address the uniformity of motive flaw by dissuading rogue behavior.[150]

Analysis of the inter-arrival times between civilizations in the galaxy based on common astrobiological assumptions suggests that the initial civilization would have a commanding lead over the later arrivals. As such, it may have established what has been termed the zoo hypothesis through force or as a galactic or universal norm and the resultant "paradox" by a cultural founder effect with or without the continued activity of the founder.[151]

It is possible that a civilization advanced enough to travel between solar systems could be actively visiting or observing Earth while remaining undetected or unrecognized.[152]

Earth is deliberately isolated (planetarium hypothesis)

A related idea to the zoo hypothesis is that, beyond a certain distance, the perceived universe is a simulated reality. The planetarium hypothesis[153] speculates that beings may have created this simulation so that the universe appears to be empty of other life.

Alien life is already here unacknowledged

A significant fraction of the population believes that at least some UFOs (Unidentified Flying Objects) are spacecraft piloted by aliens.[154][155] While most of these are unrecognized or mistaken interpretations of mundane phenomena, there are those that remain puzzling even after investigation. The consensus scientific view is that although they may be unexplained, they do not rise to the level of convincing evidence.[156]

Similarly, it is theoretically possible that SETI groups are not reporting positive detections, or governments have been blocking signals or suppressing publication. This response might be attributed to security or economic interests from the potential use of advanced extraterrestrial technology. It has been suggested that the detection of an extraterrestrial radio signal or technology could well be the most highly secret information that exists.[157] Claims that this has already happened are common in the popular press,[158][159] but the scientists involved report the opposite experience—the press becomes informed and interested in a potential detection even before a signal can be confirmed.[160]

Regarding the idea that aliens are in secret contact with governments, David Brin writes, "Aversion to an idea, simply because of its long association with crackpots, gives crackpots altogether too much influence."[161]

See also

- Aestivation hypothesis – Hypothesized solution to the Fermi paradox

- Anthropic principle – Hypothesis about sapient life and the universe

- Astrobiology – Science concerned with life in the universe

- Fermi problem – Estimation problem in physics or engineering education

- Interstellar travel – Hypothetical travel between stars or planetary systems

- Panspermia – Hypothesis on the interstellar spreading of primordial life

- Rare Earth hypothesis – Hypothesis that complex extraterrestrial life is improbable and extremely rare

- The Martians (scientists) – Group of prominent Hungarian scientists

- Wow! signal – 1977 narrowband radio signal from SETI

Notes

- ^ Of the three surviving men, only Emil Konopinski clearly remembered that Fermi's lunchtime exclamation was connected to a previous conversation which had occurred on the same day. In 1984, he wrote, "I do have a fairly clear memory of how the discussion of extra-terrestials got started—"

- ^ Teller wrote: "This incident I have clearly in mind and I believe it was on the same occasion where the other question arose which you have mentioned. This late point, however, I am not certain of."

- ^ York wrote, "At a luncheon in the Lodge which included just four people, Fermi, Teller, Emil Konoinski and myself, Fermi said, virtually apropos of nothing:"

- ^ Konopinski wrote, "I think there was only the four of us just as Herb York remembers it."

- ^ See Hart for an example of "no aliens are here", and Webb for an example of the more general "We see no signs of intelligence anywhere".

- ^ Eukaryotes also include plants, animals, fungi, and algae.

- ^ See, for example, the SETI Institute, The Harvard SETI Home Page Archived August 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, or The Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence at Berkeley Archived April 6, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pulsars are now attributed to neutron stars, and Seyfert galaxies to an end-on view of the accretion onto the black holes.

References

- ^ Woodward, Avlin (September 21, 2019). "A winner of this year's Nobel prize in physics is convinced we'll detect alien life in 100 years. Here are 13 reasons why we haven't made contact yet". Insider Inc. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- ^ Krauthammer, Charles (December 29, 2011). "Are We Alone in the Universe?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c Overbye, Dennis (August 3, 2015). "The Flip Side of Optimism About Life on Other Planets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Where is everybody?": An account of Fermi's question" Archived June 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Dr. Eric M. Jones, Los Alamos technical report, March 1985. Jones wrote to Edward Teller on July 13, 1984, Herbert York on Sept. 4, and Emil Konopinski on Sept. 24, 1984.

- ^ a b If the Universe Is Teeming with Aliens ... WHERE IS EVERYBODY?: Seventy-Five Solutions to the Fermi Paradox and the Problem of Extraterrestrial Life, Second Edition, Stephen Webb, foreword by Martin Rees, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London: Springer International Publishing, 2002, 2015.

- ^ Urban, Tim (June 17, 2014). "The Fermi Paradox". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on April 2, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ "Star (astronomy)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016. "With regard to mass, size, and intrinsic brightness, the Sun is a typical star." Technically, the sun is near the middle of the main sequence of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. This sequence contains 80–90% of the stars of the galaxy. [1] Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Grevesse, N.; Noels, A.; Sauval, A. J. (1996). "Standard abundances". ASP Conference Series. Vol. 99. p. 117. Bibcode:1996ASPC...99..117G.

The Sun is a normal star, though dispersion exists.

- ^ Buchhave, Lars A.; Latham, David W.; Johansen, Anders; et al. (2012). "An abundance of small exoplanets around stars with a wide range of metallicities". Nature. 486 (7403): 375–377. Bibcode:2012Natur.486..375B. doi:10.1038/nature11121. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 22722196. S2CID 4427321.

- ^ Schilling, G. (June 13, 2012). "ScienceShot: Alien Earths Have Been Around for a While". Science. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ Aguirre, V. Silva; G. R. Davies; S. Basu; J. Christensen-Dalsgaard; O. Creevey; T. S. Metcalfe; T. R. Bedding; et al. (2015). "Ages and fundamental properties of Kepler exoplanet host stars from asteroseismology". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 452 (2): 2127–2148. arXiv:1504.07992. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.452.2127S. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1388. S2CID 85440256.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) Accepted for publication in MNRAS. See Figure 15 in particular. - ^ a b c d Hart, Michael H. (1975). "Explanation for the Absence of Extraterrestrials on Earth". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 16: 128–135. Bibcode:1975QJRAS..16..128H.

- ^ Chris Impe (2011). The Living Cosmos: Our Search for Life in the Universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-521-84780-3.

- ^ Tsiolkovsky, K. (1933). The Planets are Occupied by Living Beings, Archives of the Tsiolkovsky State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics, Kaluga, Russia. See original text in Russian Wikisource.

- ^ Lytkin, V.; Finney, B.; Alepko, L. (December 1995). "Tsiolkovsky – Russian Cosmism and Extraterrestrial Intelligence". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 36 (4): 369. Bibcode:1995QJRAS..36..369L.

- ^ Webb, Stephen (2015). If the Universe Is Teeming with Aliens ... WHERE IS EVERYBODY?: Seventy-Five Solutions to the Fermi Paradox and the Problem of Extraterrestrial Life (2 ed.). Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-13235-8. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Forgan, Duncan H. (2019). Solving Fermi's Paradox. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-73231-1. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b "The 'Great Silence': The Controversy Concerning Extraterrestrial Intelligent Life", Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, Glen David Brin, Volume 24: pp. 283–297, 3rd quarter of 1983 (received Sept. 1982).

- ^ Annis, James (1999). "An Astrophysical Explanation for the Great Silence". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 52 (1): 19. arXiv:astro-ph/9901322. Bibcode:1999JBIS...52...19A.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2007). "In Great Silence there is Great Hope" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Milan M. Ćirković (2009). "Fermi's Paradox – The Last Challenge for Copernicanism?". Serbian Astronomical Journal. 178 (178): 1–20. arXiv:0907.3432. Bibcode:2009SerAJ.178....1C. doi:10.2298/SAJ0978001C. S2CID 14038002.

- ^ Shostak, Seth (October 25, 2001). "Our Galaxy Should Be Teeming With Civilizations, But Where Are They?". Space.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2006. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ Dunn, Alan (May 20, 1950). "uncaptioned cartoon". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 15, 2010.

- ^ Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience, edited by Ben R. Finney, Eric M. Jones, University of California Press, 1985.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (June 3, 2013). "How Many Stars are There in the Universe?". Universe Today. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- ^ Craig, Andrew (July 22, 2003). "Astronomers count the stars". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ a b Crawford, I.A., "Where are They? Maybe we are alone in the galaxy after all" Archived December 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Scientific American, July 2000, 38–43, (2000).

- ^ Shklovskii, Iosif; Sagan, Carl (1966). Intelligent Life in the Universe. San Francisco: Holden–Day. ISBN 978-1-892803-02-3.

- ^ J. Richard Gott, III. "Chapter 19: Cosmological SETI Frequency Standards". In Zuckerman, Ben; Hart, Michael (eds.). Extraterrestrials; Where Are They?. p. 180.

- ^ Gowdy, Robert H., VCU Department of Physics SETI: Search for ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence. The Interstellar Distance Problem Archived December 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, 2008

- ^ Sandberg, Anders; Drexler, Eric; Ord, Toby (June 6, 2018). "Dissolving the Fermi Paradox". arXiv:1806.02404 [physics.pop-ph].

- ^ Drake, F.; Sobel, D. (1992). Is Anyone Out There? The Scientific Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Delta. pp. 55–62. ISBN 978-0-385-31122-9.

- ^ Barrow, John D.; Tipler, Frank J. (1986). The Anthropic Cosmological Principle (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 588. ISBN 978-0-19-282147-8. LCCN 87028148.

- ^ Anders Sandberg; Eric Drexler; Toby Ord (June 6, 2018). "Dissolving the Fermi Paradox". arXiv:1806.02404 [physics.pop-ph].

- ^ Hanson, Robin (1998). "The Great Filter – Are We Almost Past It?". Archived from the original on May 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c Paleontological Tests: Human Intelligence is Not a Convergent Feature of Evolution. Archived December 20, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Charles Lineweaver, Australian National University, Canberra, published in From Fossils to Astrobiology, edited by J. Seckbach and M. Walsh, Springer, 2009.

- ^ Schulze-Makuch, Dirk; Bains, William (2017). The Cosmic Zoo: Complex Life on Many Worlds. Springer. pp. 201–206. ISBN 978-3-319-62045-9.

- ^ Behroozi, Peter; Peeples, Molly S. (December 1, 2015). "On The History and Future of Cosmic Planet Formation". MNRAS. 454 (2): 1811–1817. arXiv:1508.01202. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.454.1811B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1817. S2CID 35542825.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sohan Jheeta (2013). "Final frontiers: the hunt for life elsewhere in the Universe". Astrophys Space Sci. 348 (1): 1–10. Bibcode:2013Ap&SS.348....1J. doi:10.1007/s10509-013-1536-9. S2CID 122750031.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (1975). "Discovery of pulsars: a graduate student's story". Science. 189 (4200): 358–364. Bibcode:1975Sci...189..358W. doi:10.1126/science.189.4200.358. PMID 17840812. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "NASA/CP2007-214567: Workshop Report on the Future of Intelligence in the Cosmos" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 11, 2014.

- ^ Duncan Forgan, Martin Elvis; Elvis (March 28, 2011). "Extrasolar Asteroid Mining as Forensic Evidence for Extraterrestrial Intelligence". International Journal of Astrobiology. 10 (4): 307–313. arXiv:1103.5369. Bibcode:2011IJAsB..10..307F. doi:10.1017/S1473550411000127. S2CID 119111392.

- ^ Whitmire, Daniel P.; David P. Wright. (1980). "Nuclear waste spectrum as evidence of technological extraterrestrial civilizations". Icarus. 42 (1): 149–156. Bibcode:1980Icar...42..149W. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(80)90253-5.

- ^ Mullen, Leslie (2002). "Alien Intelligence Depends on Time Needed to Grow Brains". Astrobiology Magazine. Space.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2003. Retrieved April 21, 2006.

- ^ Brian von Konsky (October 23, 2000). "Radio Leakage: Is anybody listening?". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.548.8184.

- ^ Scheffer, L. (2004). "Aliens can watch 'I Love Lucy'". Contact in Context. 2 (1).

- ^ Participants, NASA (2018). "NASA and the Search for Technosignatures: A Report from the NASA Technosignatures Workshop". arXiv:1812.08681 [astro-ph.IM].

- ^ Udry, Stéphane; Bonfils, Xavier; Delfosse, Xavier; Forveille, Thierry; Mayor, Michel; Perrier, Christian; Bouchy, François; Lovis, Christophe; Pepe, Francesco; Queloz, Didier; Bertaux, Jean-Loup (2007). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets XI. Super-Earths (5 and 8 ME) in a 3-planet system" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 469 (3): L43–L47. arXiv:0704.3841. Bibcode:2007A&A...469L..43U. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077612. S2CID 119144195. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2010.

- ^ From "Kepler: About the Mission". NASA. March 31, 2015. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2016. "The Kepler Mission, NASA Discovery mission #10, is specifically designed to survey a portion of our region of the Milky Way galaxy to discover dozens of Earth-size planets in or near the habitable zone and determine how many of the billions of stars in our galaxy have such planets."

- ^ Gray, Robert H. (March 2015). "The Fermi Paradox Is Neither Fermi's Nor a Paradox". Astrobiology. 15 (3): 195–199. doi:10.1089/ast.2014.1247.

- ^ Dick, Steven J. (2020). "Bringing Culture to Cosmos: Cultural Evolution, the Postbiological Universe, and SETI". Space, Time, and Aliens: Collected Works on Cosmos and Culture. Springer International Publishing: 171–190. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-41614-0_12. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Bracewell, R. N. (1960). "Communications from Superior Galactic Communities". Nature. 186 (4726): 670–671. Bibcode:1960Natur.186..670B. doi:10.1038/186670a0. S2CID 4222557.

- ^ Papagiannis, M. D. (1978). "Are We all Alone, or could They be in the Asteroid Belt?". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 19: 277–281. Bibcode:1978QJRAS..19..277P.

- ^ Robert A. Freitas Jr. (November 1983). "Extraterrestrial Intelligence in the Solar System: Resolving the Fermi Paradox". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. Vol. 36. pp. 496–500. Bibcode:1983JBIS...36..496F. Archived from the original on December 8, 2004. Retrieved November 12, 2004.

- ^ Freitas, Robert A Jr; Valdes, F (1985). "The search for extraterrestrial artifacts (SETA)". Acta Astronautica. 12 (12): 1027–1034. Bibcode:1985AcAau..12.1027F. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.118.4668. doi:10.1016/0094-5765(85)90031-1.

- ^ Dyson, Freeman J. (1960). "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infra-Red Radiation". Science. 131 (3414): 1667–1668. Bibcode:1960Sci...131.1667D. doi:10.1126/science.131.3414.1667. PMID 17780673. S2CID 3195432. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ a b Wright, J. T.; Mullan, B.; Sigurðsson, S.; Povich, M. S. (2014). "The Ĝ Infrared Search for Extraterrestrial Civilizations with Large Energy Supplies. I. Background and Justification". The Astrophysical Journal. 792 (1): 26. arXiv:1408.1133. Bibcode:2014ApJ...792...26W. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/792/1/26. S2CID 119221206.

- ^ a b Wright, J. T.; Griffith, R.; Sigurðsson, S.; Povich, M. S.; Mullan, B. (2014). "The Ĝ Infrared Search for Extraterrestrial Civilizations with Large Energy Supplies. II. Framework, Strategy, and First Result". The Astrophysical Journal. 792 (1): 27. arXiv:1408.1134. Bibcode:2014ApJ...792...27W. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/792/1/27. S2CID 16322536.

- ^ "Fermilab Dyson Sphere search program". Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. Archived from the original on March 6, 2006. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ Wright, J. T.; Mullan, B; Sigurdsson, S; Povich, M. S (2014). "The Ĝ Infrared Search for Extraterrestrial Civilizations with Large Energy Supplies. III. The Reddest Extended Sources in WISE". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 217 (2): 25. arXiv:1504.03418. Bibcode:2015ApJS..217...25G. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/217/2/25. S2CID 118463557.

- ^ "Alien Supercivilizations Absent from 100,000 Nearby Galaxies". Scientific American. April 17, 2015. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Wright, Jason T.; Cartier, Kimberly M. S.; Zhao, Ming; Jontof-Hutter, Daniel; Ford, Eric B. (2015). "The Ĝ Search for Extraterrestrial Civilizations with Large Energy Supplies. IV. The Signatures and Information Content of Transiting Megastructures". The Astrophysical Journal. 816 (1): 17. arXiv:1510.04606. Bibcode:2016ApJ...816...17W. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/816/1/17. S2CID 119282226.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Andersen, Ross (October 13, 2015). "The Most Mysterious Star in Our Galaxy". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- ^ Boyajian, Tabetha S.; et al. (2018). "The First Post-Kepler Brightness Dips of KIC 8462852". The Astrophysical Journal. 853 (1). L8. arXiv:1801.00732. Bibcode:2018ApJ...853L...8B. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aaa405. S2CID 215751718.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Overbye, Dennis (January 10, 2018). "Magnetic Secrets of Mysterious Radio Bursts in a Faraway Galaxy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ Ward, Peter D.; Brownlee, Donald (2000). Rare Earth: Why Complex Life is Uncommon in the Universe (1st ed.). Springer. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-387-98701-9.

- ^ The Nature of Nature: Examining the Role of Naturalism in Science, editors Bruce Gordon and William Dembski, Ch. 20 "The Chain of Accidents and the Rule of Law: The Role of Contingency and Necessity in Evolution" by Michael Shemer, published by Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2010.

- ^ Steven V. W. Beckwith (2008). "Detecting Life-bearing Extrasolar Planets with Space Telescopes". The Astrophysical Journal. 684 (2): 1404–1415. arXiv:0710.1444. Bibcode:2008ApJ...684.1404B. doi:10.1086/590466. S2CID 15148438.

- ^ Sparks, W.B.; Hough, J.; Germer, T.A.; Chen, F.; DasSarma, S.; DasSarma, P.; Robb, F.T.; Manset, N.; Kolokolova, L.; Reid, N.; et al. (2009). "Detection of circular polarization in light scattered from photosynthetic microbes" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (14–16): 1771–1779. doi:10.1016/j.jqsrt.2009.02.028. hdl:2299/5925.

- ^ a b Tarter, Jill (2006). "What is SETI?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 950 (1): 269–275. Bibcode:2001NYASA.950..269T. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02144.x. PMID 11797755. S2CID 27203660.

- ^ "Galaxy Simulations Offer a New Solution to the Fermi Paradox", Quanta Magazine "Abstraction Blog," Rebecca Boyle, March 7, 2019. “The sun has been around the center of the Milky Way 50 times," said Jonathan Carroll-Nellenback, astronomer at the University of Rochester.

- ^ "The Aliens Are Silent Because They Are Extinct". Australian National University. January 21, 2016. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Melott AL, Lieberman BS, Laird CM, Martin LD, Medvedev MV, Thomas BC, Cannizzo JK, Gehrels N, Jackman CH (2004). "Did a gamma-ray burst initiate the late Ordovician mass extinction?" (PDF). International Journal of Astrobiology. 3 (1): 55–61. arXiv:astro-ph/0309415. Bibcode:2004IJAsB...3...55M. doi:10.1017/S1473550404001910. hdl:1808/9204. S2CID 13124815. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ Nick Bostrom; Milan M. Ćirković. "12.5: The Fermi Paradox and Mass Extinctions". Global catastrophic risks.

- ^ Loeb, Abraham (January 8, 2018). "Are Alien Civilizations Technologically Advanced?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, George (August 18, 2014). "The Intelligent-Life Lottery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b "Why David Brin Hates Yoda, Loves Radical Transparency". Wired. August 8, 2012. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019.

- ^ a b von Hoerner, Sebastian (December 8, 1961). "The Search for Signals from Other Civilizations". Science. 134 (3493): 1839–1843. Bibcode:1961Sci...134.1839V. doi:10.1126/science.134.3493.1839. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17831111.

- ^ Hite, Kristen A.; Seitz, John L. (2020). Global Issues : an introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-119-53850-9. OCLC 1127917585.

- ^ Webb, Stephen (2015). If the Universe Is Teeming with Aliens... Where Is Everybody? Seventy five Solutions to the Fermi Paradox and the Problem of Extraterrestrial Life (2nd ed.). Copernicus Books. ISBN 978-3-319-13235-8. Archived from the original on September 3, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015. Chapters 36–39.

- ^ Sotos, John G. (January 15, 2019). "Biotechnology and the lifetime of technical civilizations". International Journal of Astrobiology. 18 (5): 445–454. arXiv:1709.01149. Bibcode:2019IJAsB..18..445S. doi:10.1017/s1473550418000447. ISSN 1473-5504. S2CID 119090767.

- ^ Bohannon, John (November 29, 2010). "Mirror-image cells could transform science – or kill us all". Wired. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Frank, Adam (January 17, 2015). "Is a Climate Disaster Inevitable?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick. "Existential Risks Analyzing Human Extinction Scenarios and Related Hazards". Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ Sagan, Carl. "Cosmic Search Vol. 1 No. 2". Cosmic Search Magazine. Archived from the original on August 18, 2006. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Hawking, Stephen. "Life in the Universe". Public Lectures. University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on April 21, 2006. Retrieved May 11, 2006.

- ^ Yudkowsky, Eliezer (2008). "Artificial Intelligence as a Positive and Negative Factor in Global Risk". In Bostrom, Nick; Ćirković, Milan M. (eds.). Global catastrophic risks. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 308–345. ISBN 978-0-19-960650-4. OCLC 993268361.

- ^ Billings, Lee (June 13, 2018). "Alien Anthropocene: How Would Other Worlds Battle Climate Change?". Scientific American. Vol. 28, no. 3s. Springer Nature. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "The Great Silence: the Controversy . . . " (15-page paper), Quarterly J. Royal Astron. Soc., David Brin, 1983, page 301 second-to-last paragraph Archived May 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Brin cites, The Prehistory of Polynesia, edited by J. Jennings, Harvard University Press, 1979. See also Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience, edited by Ben Finney and Eric M. Jones, Ch. 13 "Life (With All Its Problems) in Space" by Alfred W. Crosby, University of California Press, 1985.

- ^ "The Great Silence: the Controversy . . . " (15-page paper), Quarterly J. Royal Astron. Soc., David Brin, 1983, page 296 bottom third Archived February 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Self-Reproducing Machines from Another Planet : THE FORGE OF GOD by Greg Bear (Tor Books : $17.95; 448 pp.)". Los Angeles Times. September 20, 1987. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022.

- ^ Soter, Steven (2005). "SETI and the Cosmic Quarantine Hypothesis". Astrobiology Magazine. Space.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved May 3, 2006.

- ^ Archer, Michael (1989). "Slime Monsters Will Be Human Too". Aust. Nat. Hist. 22: 546–547.

- ^ a b c Webb, Stephen (2002). If the Universe Is Teeming with Aliens... Where Is Everybody? Fifty solutions to the Fermi Paradox and the Problem of Extraterrestrial Life. Copernicus Books. ISBN 978-0-387-95501-8. Archived from the original on September 3, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Berezin, Alexander (March 27, 2018). "'First in, last out' solution to the Fermi Paradox". arXiv:1803.08425v2 [physics.pop-ph].

- ^ Dockrill, Peter (June 2, 2019). "A Physicist Has Proposed a Pretty Depressing Explanation For Why We Never See Aliens". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ Marko Horvat (2007). "Calculating the probability of detecting radio signals from alien civilizations". International Journal of Astrobiology. 5 (2): 143–149. arXiv:0707.0011. Bibcode:2006IJAsB...5..143H. doi:10.1017/S1473550406003004. S2CID 54608993. "There is a specific time interval during which an alien civilization uses radio communications. Before this interval, radio is beyond the civilization's technical reach, and after this interval radio will be considered obsolete."

- ^ Stephenson, D. G. (1984). "Solar Power Satellites as Interstellar Beacons". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 25 (1): 80. Bibcode:1984QJRAS..25...80S.

- ^ The Future of SETI Archived May 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Sky & Telescope, Seth Shostak, July 19, 2006. This article also discusses strategy for optical SETI.

- ^ Scharf, Caleb (August 10, 2022). "We Might Already Speak the Same Language As ET". Nautilus Quarterly. Retrieved August 11, 2022.

- ^ "Cosmic Search Vol. 1 No. 3". Bigear.org. September 21, 2004. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- ^ Learned, J; Pakvasa, S; Zee, A (2009). "Galactic neutrino communication". Physics Letters B. 671 (1): 15–19. arXiv:0805.2429. Bibcode:2009PhLB..671...15L. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.11.057. S2CID 118453255.

- ^ Schombert, James. "Fermi's paradox (i.e. Where are they?)" Archived November 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Cosmology Lectures, University of Oregon.

- ^ Hamming, RW (1998). "Mathematics on a distant planet". The American Mathematical Monthly. 105 (7): 640–650. doi:10.2307/2589247. JSTOR 2589247.

- ^ Carl Sagan. Contact. Chapter 3, p. 49.

- ^ Istvan, Zoltan (March 16, 2016). "Why Haven't We Met Aliens Yet? Because They've Evolved into AI". Motherboard. Vice Media. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.